Self-Awareness

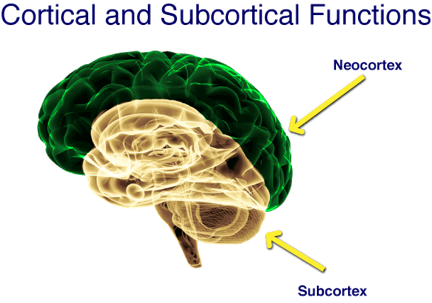

New findings suggest how brain regions involved in self-awareness help us with ethics and with decision making in general. The key to understanding this neural dynamic is to distinguish between the thinking brain (neocortex), and the subcortical areas.

The neocortex – the wavy areas in green – contains centers for cognition and other complex mental operations. The subcortical areas, shown here in blue, are where more basic mental processes occur. Just below the thinking brain, and projecting into the cortex, are the limbic centers, the brain’s main areas for emotion. These areas are also found in the brains of other mammals. The more ancient parts of the subcortex extend down to the brainstem, known as the “reptilian brain” because we share this basic architecture with reptiles.

Antonio Damasio (the neuroscientist in whose lab Bar-On’s work on the brain basics of EI was done) has written about a telling neurological case. There was a brilliant corporate lawyer who, unfortunately, had a brain tumor. Luckily that tumor was diagnosed early and operated on successfully. But during the operation the surgeon had to cut circuits that connect key areas of the prefrontal cortex, the brain’s executive center, and the amygdala in the midbrain’s area for emotions.

After the surgery there was a very puzzling clinical picture. On every test of IQ, memory, and attention, this lawyer was absolutely as smart as he had been before the surgery. But he couldn't do his job any more. He lost his job. He couldn't keep any job. His marriage broke up. He lost his house. He ended up living in his brother’s spare bedroom and, in despair, he went to Damasio to find out what was wrong.

At first Damasio was completely puzzled, because on every neurological test, the lawyer was fine. But the clue came when Damasio asked the lawyer, “When shall we have our next appointment?”

It was then that Damasio realized the lawyer could give him the rational pros and cons of every hour for the next two weeks – but he didn't know which was best. Damasio says that in order to make a good decision, we need to have feelings about our thoughts – and that lesion created during the surgery for the lawyer’s tumor meant he could no longer connect his thoughts with the emotional pros and cons.

Such feelings come from the emotional centers in the midbrain, interacting with a specific area in the prefrontal cortex7. When we have a thought it’s immediately valenced by these brain centers, positive or negative. This is what helps us shuffle our thoughts into priorities – like when would be the best time for an appointment. Lacking that input, we don't know what to feel about our thoughts, so we can't make good decisions.

Cortical-subcortical circuitry also offers an ethical rudder. Lower in the brain, below the limbic areas, lies a neural network called the basal ganglia. This is a very primitive part of the brain, but it does something extraordinarily important for navigating the modern world.

As we go through every situation in life, the basal ganglia extracts decision rules: when I did that, that worked well; when I said this, it bombed, and so on. Our accumulated life wisdom is stored in this primitive circuitry. However, when we face a decision, it’s our verbal cortex that generates our thoughts about it. But to more fully access our life experience on the matter at hand, we need to access further inputs from that subcortical circuitry. While the basal ganglia have some direct connection to the verbal areas, it turns out also to have very rich connections to the gastrointestinal tract – the gut. So in making the decision, a gut sense of it being right or wrong is important information, too8. It’s not that you should ignore the data, but if it doesn't fit what you're feeling, maybe you should think twice about it.

That rule-of-thumb seemed to be at play in a study of highly successful California entrepreneurs who were asked how they made crucial business decisions. They all reported more or less the same strategy. First, they were voracious consumers of any data or information that might bear on their decision, casting a wide net. But second, they all tested their rational decision against their gut feeling – if a deal didn’t feel right they might not go ahead, even if it looked good on paper.

The answer to the question, “Is what I'm about to do in keeping with my sense of purpose, meaning, or ethics?” doesn't come to us in words; it comes to us via this gut sense. Then we put it into words.