1

Dangerously Famous

IN 1920S EUROPE, Carl Jung was a celebrity and regarded as the chief rival of the great Sigmund Freud. While Freud had carved out the new field of psychoanalysis, it was Jung who made it fashionable. He extended the boundaries by using dream images to explore the unconscious more deeply than Freud had, probing into the archetypes built into our minds. He was a spell-binding lecturer and recipient of adulation both from colleagues and a host of women whom he referred to as his “fur-coat ladies.” The rich and famous flocked to his fortresslike mansion on the shore of Lake Zürich, not only as prospective patients but also to enjoy his inspiring conversation. Among them were the McCormicks of the Chicago newspaper dynasty, H. G. Wells, and Hugh Walpole, who remembered him as looking “like a large genial cricketer.” Some came just to gaze at the “primitive” who washed his own jeans with his “powerful arms” on the lawn outside his mansion.

Jung was, as he said himself, “dangerously famous,” so much so that patients sometimes had to wait a year for an appointment. Psychoanalysis had become all the rage and “going to Jung was somehow very chic and modern,” as a wealthy American female client put it.

But there was still something missing. Jung was concerned that his approach to psychoanalysis needed a scientific underpinning, but he didn’t have the requisite scientific background. To develop his ideas, he needed to work with someone who was au fait with the latest developments in science.

Boyhood

Jung was born on July 26, 1875, in the village of Kesswil on Lake Constance, on the northern border of Switzerland, to an impoverished Protestant pastor with a passion for learning. His mother, Emilie, had had three stillborn children before young Carl’s arrival and had withdrawn into a world of ghosts and spirits. Jung’s father moved from parish to parish but nothing seemed to help her. This often enraged him, leading to violent arguments between the two, during which young Carl would take refuge in his father’s book-lined study.

Embarrassed by his shabby clothes and poverty, the boy for the most part kept away from others. His main interest was in his own rich dreams, in ghosts, in stories of the supernatural, and in séances. His charmed solitude came to an end with the birth of a sister, when he was nine. From then on he had to share with her the little attention he received from his parents.

Young Carl spent long periods of time staring at a stone and talking to it. One day he carved the top of a wooden ruler into a manikin and painted it to look like a village elder. He hid it in the attic, took it presents, and even wrote letters to it. Years later, he realized that what he had created was actually a totem—a primeval object of worship. It was a straightforward case of “archaic psychic components” entering “the individual psyche without any direct line of tradition.” Thus he found in himself what he would later call the “collective unconscious.”

By the age of eleven young Carl’s brilliance was clear. He was also bigger and stronger than his classmates and always up for a fight. By fifteen he had read most of the books in his father’s study, from adventure novels to Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra and Goethe’s Faust (both “a tremendous experience for me,” he recalled), as well as Kant, the Grail legends, and Shakespeare.

Jung’s family was so poor that the only university he could go to was Basel, near enough that he could live at home. The question was what to study. He was interested in archaeology, but the university did not offer it. Then he had two dreams. In one he was digging up the bones of ancient animals, while the other concerned protozoa. From this he decided he should study some form of natural science. But if he studied zoology he would be bound to end up as a teacher. So he opted for medicine, even though his father had to petition for a stipend to support him. He started at the university in 1895.

Jung’s calling

By his final year Jung had realized that his real interest lay in probing the secrets of the psyche: “Here, finally, was the place where nature would collide with spirit.” Following up his childhood interest in dreams and ghosts, he wrote a dissertation entitled “On the Psychology and Pathology of the So-Called Occult Phenomena.”

After a brilliant university career, Jung was immediately offered a position at the Burghölzli Mental Hospital by its director, the world-famous Dr. Eugen Bleuler, who had coined the term “schizophrenia.” The hospital is in Zürich, sixty miles from Basel. Jung began work there in December 1900, when he was twenty-five. Physically so big that he dwarfed colleagues, handsome and brimming with enthusiasm, with a voice and laugh so loud they filled the room, Jung had a magnetic presence. He soon became the director’s protégé.

A huge, sprawling, austere building, the Burghölzli loomed over Lake Zürich. To discourage thoughts of suicide it was built in such a way that none of the inmates could see the water. Inside, the building was sparse. Apart from the doctors’ offices there were no comfortable chairs, only wooden benches. The working day at Burghölzli rarely ended before 10 p.m. Jung found the regime exhausting and missed the intellectual life of Basel with its late night philosophical conversations. But he was convinced that psychiatry was his metier.

Emma

Four years earlier, Jung had met Emma Rauschenbach, a fascinating fourteen-year-old girl from a very wealthy family. She was an heiress, the second richest in Switzerland. Her father owned a vast manufacturing empire that produced, among other things, machine-made watches, which were then a novelty. However, it was not Emma’s wealth that attracted him to her. Jung always insisted most emphatically that he had not married her for her money. He once confided to a friend that he had fallen instantly in love the first time he saw her and felt sure they would marry some day. The friend, sadly to say, laughed.

In 1901 he was invited to a party in the town of Winterhur, where he met her again. She had grown into a beautiful young woman with dark hair, wide expressive eyes, and a ready smile. Having lived for a year in Paris, she spoke French and read Old French and Provençal. She was deeply interested in the legends of the Holy Grail, as was Jung. That summer her mother invited Jung to a ball at their elegant summer residence, the Ölberg, outside Schaffhausen. It covered several acres and there were scores of servants and gardeners. Jung’s cardboard collar, tattered clothes, and rough manners were in sharp contrast to the well-heeled crowd. To add to his problems Emma was already betrothed to the son of a business associate of her father’s.

Undaunted, he set about courting her. Emma was attracted to his good looks and brilliance. But more than that he seemed to value her intelligence and encouraged her to broaden it, qualities she found lacking in the other men who pursued her. In his numerous letters he suggested books she might read on subjects that included literature and psychology. She came to believe that more than just a wife to him, she could be a partner in his professional life. His courtship was boosted immensely by clandestine help from his future mother-in-law, who had come to realize her daughter’s growing affection for the poor but affable Dr. Jung. Eventually she convinced her husband of the young man’s seriousness and that her daughter’s happiness was of paramount importance.

The two married in 1903 in a lavish ceremony held at the Swiss Reformed Church in Schaffhausen. Two days later, in the best hotel in town, there was a sumptuous wedding banquet of twelve courses, each accompanied by the proper wine.

Carl and Emma Jung at the time of their marriage, February 14, 1903.

Emma took on the task of transcribing the voluminous notes Jung made during his hospital rounds. The following year they had their first child. Emma’s substantial wealth gave Jung the freedom to pursue his own research and he quickly came to the attention of the international psychoanalytic community. By 1906 he had been appointed senior doctor at the Burghölzli, second only to Bleuler.

The fur-coat ladies

Jung had also started lecturing at the University of Zürich, where he held students spellbound. He ranged over not only psychiatry but also history, culture, mysticism, hysteria, and family dynamics, focusing particularly on women’s problems. Many in his audience were wealthy women from Zürich’s high society—his “fur-coat ladies.” After lectures they would flock to talk to him.

Some of the fur-coat ladies began to invite the professor back to their homes for private consultations. There were no ethical guidelines in psychoanalysis in those days and the treatment sessions, often intense, sometimes ended in sex. Jung’s flirtations began to get out of hand. But the more dangerous they became, the more they excited him. He bragged of his “heroic efforts” to keep his female patients at arm’s length. The hospital community was small and gossip quickly spread.

Emma was painfully aware of her husband’s infidelities. Eager to placate her, he resigned from the Burghölzli, allowed her to assume a larger role in his day-to-day work, and built a new house for their growing family in Küsnacht, outside Zürich. She was pregnant with their third child in another effort to bring the family closer.

Jung even analyzed Emma to convince her that the rumors of his infidelities were untrue. In fact this was far from the case. As he wrote to Freud, “the prerequisite for a good marriage is license to be unfaithful.” Jung soon resumed his infidelities. Whenever Emma threatened divorce he would suddenly become incapacitated, claiming fatigue from overwork or suffering a serious accident such as falling down stairs. Emma would have to drop everything to nurse him back to health. Eventually she resigned herself to the situation.

Jung meets Freud

Jung first became famous for his word-association tests. In these he measured patients’ responses to stimulus words such as “mother,” “father,” and “sad,” and noted cases where they did not reply or hesitated before replying. He concluded that the slower the response, the more deeply the patient was delving into his unconscious. The speed and quality of the responses, he wrote, could be explained by the action of “feeling-toned complexes,” which he later abbreviated to “complexes.” These, he suggested, existed below the conscious level and could only be perceived when the patient’s threshold of attention was lowered by using stimulus words.

Like Freud he claimed that experiments of this sort were proof of the unconscious. But while he agreed with Freud’s hypothesis that there was a personal unconscious that was constructed out of worldly experiences, he was also beginning to sense the presence of a deeper shared unconscious that could only be imagined.

His conclusions seemed to square with Freud’s concept of repression in which people kept their neuroses locked up in their unconscious. The role of the psychoanalyst, in Freud’s view, was to root them out to improve the patient’s conscious life. Jung disagreed with Freud’s hypothesis that sexual trauma was the primary cause of repression. He was eager to meet Freud and talk through these points of difference and in 1907 arranged to visit him in Vienna.

On that first historic meeting, Jung arrived at Freud’s apartment for lunch at 1 p.m. and left some thirteen hours later. The main point of contention was Jung’s belief that parapsychology deserved to be classed as a scientific field. Born in 1856, Freud was nineteen years older than Jung. He was only five foot seven, but his immaculate grooming, sharply observant eyes, and ever-present cigar gave him an aura of authority.

Freud’s eldest son Martin was present and recalled vividly Jung’s “commanding presence. He was very tall and broad shouldered, holding himself more like a soldier than a man of science and medicine. His head was purely Teutonic with a strong chin, a small moustache and thin close-cropped hair.” Jung dominated the meeting with stories of his cases and new ideas told with great enthusiasm. Freud was delighted. The man with whom he had been corresponding met his every expectation—except one.

Freud clung to the late-nineteenth-century view that the mind, like everything else, could be reduced to matter and understood through physics and chemistry, subjects that he had studied in some detail as a medical student, in a daring departure from the traditional curriculum. This approach—known as “positivism”—had been founded by the philosopher and physicist Ernst Mach. Mach claimed that science could only study data obtainable in the laboratory and which could ultimately be experienced with the senses, such as direct touch.

Freud had begun his career as a medical researcher in neurology. This work further supported his view of the brain as a mechanism. But it was the teachings of the then-master-neurologist Jean Martin Charcot in Paris on the use of hypnosis to study hysteria—itself seen as a disease of the nervous system—as well as the analytic methods of the Austrian physician Josef Breuer that launched Freud on the route to his everlasting fame. Having found that hypnotizing patients with hysteria was often unsuccessful, he tried a “talking cure,” in which patients talked through their problems. Thus was psychoanalysis born. Most of the fundamentals had been worked out by Breuer, Charcot, and Pierre Janet, the famous French psychologist, among others. Freud’s genius was in putting them all together and then devising ways systematically to study the unconscious.

Although Jung initially considered a career in brain anatomy, his experiences at the Burgölzli led him to return to his original interest in regions of the unconscious that Freud, with his positivistic turn of mind, dared not enter—the world of the collective unconscious with its archetypes. Parapsychology, he was convinced, was a way to probe it. Jung often turned the tables on Freud by arguing that Freud’s views on sexuality were as unprovable as his own on parapsychology in any strictly scientific sense, especially the positivistic one.

Eight months after their first meeting he wrote to Freud, “I have been dabbling in spookery again.” He could not resist any opportunity to remind Freud of his interest in parapsychology.

Mach himself once remarked acerbically on Freud and his school of psychoanalysis, “These people try to use the vagina as if it were a telescope so that they can see the world through it. But that is not its natural function—it is too narrow for that.”*

The debate between Jung and Freud on parapsychology and sexuality continued for several years. Jung strongly believed that the human psyche was much too complex to be understood merely in terms of the libido. Conversely, when Jung visited Freud in the spring of 1909, Freud categorically rejected the entire field of parapsychology, which Jung so fervently believed in, as “nonsensical.” He offered supporting arguments, Jung recalled, in “terms of so shallow a positivism that I had difficulty in checking the sharp retort on the tip of my tongue. While Freud was going on in this way I had a curious sensation. It was as if my diaphragm were made of iron and were becoming red-hot—a glowing vault.”

As the two were arguing, there was a loud report in the bookcase next to them. They both jumped back, fearing it would fall on top of them. “I said to Freud,” continued Jung, “there, that is an example of a so-called catalytic exteriorization phenomenon”—a physical effect brought about by a mental thought. “Sheer bosh,” replied Freud. He dismissed Jung’s explanation of what had happened as occult nonsense. They never again discussed the incident.

That very evening Freud named Jung as his successor in the psychoanalytic movement and adopted him as an eldest son. A month later he wrote Jung accusing him of taking away all the pleasure of the moment and divesting “him of any paternal dignity.”

Around this time Jung had been treating Joseph Medill McCormick of the McCormick newspaper dynasty, for alcoholism. When he suddenly managed to bring about a cure, he overnight developed a huge reputation in the United States. Later that year he was invited to lecture at a symposium at Clark University, in Worcester, Massachusetts. Freud too was invited to lecture and the two traveled together. As they sailed into New York harbor, Freud turned to Jung and said, “If they only knew what we are bringing to them.” During the crossing to the United States the two were together for a week, and often analyzed each other’s dreams. In the course of analyzing one of Freud’s, Jung asked him for details of his private life. Freud replied, “But I cannot risk my authority!” “That sentence burned itself into my memory,” Jung remembered. “Freud was placing personal authority above truth.”

In the United States Freud had a miserable time and suffered anxiety attacks, but Jung fell in love with the New World. He traveled to Maine and New York, where he immersed himself in the Egyptian, Cypriot, and Cretan collections at the Metropolitan Museum and studied the tapestries at the Pierpont Morgan Library and the palaeontology collections at the American Museum of Natural History.

He also met up with the Harvard philosopher and psychologist William James, brother of the novelist Henry James. The two immediately bonded. They discussed parapsychology, spiritualism, faith healing, and other nonmedical applications of psychotherapy, all of which went well beyond Freud’s view of the psyche.

Jung was convinced that Freud’s focus on sex limited his intellectual horizons. As far as Jung was concerned, Freud employed literal interpretations and so, for instance, “could not grasp the spiritual significance of incest as a symbol.” For Jung sex played no more than a role in the psyche. He was more interested in its “spiritual aspect and its numinous meaning.” Freud claimed that he was so far above sexual inclinations himself that he could judge a patient’s sexual disorders objectively. Jung, however, had begun to suspect that Freud was involved in an ongoing affair with his sister-in-law and even claimed that she had confessed it to him.

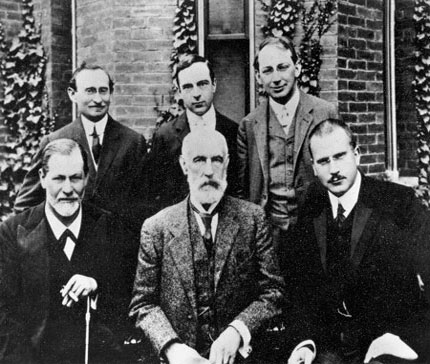

Clark University, 1909. Sigmund Freud is seated on the left; Carl Jung is seated on the right.

The tempestuous relationship between the two masters of psychoanalysis seemed likely to end in disaster. Yet between them they brought psychoanalysis to the New World.

The collective unconscious

Both Freud and Jung worked by analyzing dreams. But while Freud did so to probe an unconscious that he postulated as being made up of everyday experiences, Jung was interested in dreams as the portal to something that transcended the individual—a shared or collective unconscious.

Jung’s dreams were steeped in symbolic content. In one he was in a house, on the second floor. As he came downstairs he seemed to slip back in time. In the basement there were two skulls. Freud regularly interpreted dreams in terms of two conflicting drives in our mental life—the life drive (which includes sex) and the death drive. He was convinced there was a secret death-wish in Jung’s dream and suggested that it meant Jung wanted to murder someone. Driven into a corner, Jung jokingly suggested it must be his wife and sister-in-law. To his amazement Freud was greatly relieved for it appeared to support his analysis. For Jung, conversely, the ground floor simply represented the first level of his unconscious, and so on into the depths. The dream of the house revived Jung’s old interest in archaeology and symbolism. Crusaders and the Holy Grail began to enter his dreams.

Another dream that contained more than Jung initially realized was that of “the solar phallus man.” A severely schizophrenic patient interned at Burghölzli claimed that he had had a vision of a phallus hanging from the sun. When it swayed it produced weather and also allowed God to spread His semen. In those politically incorrect days, all the doctors, including Jung, thought this hilarious. Then, one day, Jung happened to read a book on Mithraic mythology. It described a liturgy of exactly the sort imagined by the schizophrenic patient. Jung knew for certain that the patient had never seen this book, or any like it. It seemed to provide firm evidence of what Jung was to dub, in 1913, the collective unconscious.

Freud saw the unconscious as a storehouse of repressed emotions, thoughts, and memories, an arena where a day-to-day struggle took place among the id, ego, and superego with a strong sexual undercurrent. Jung, conversely, was interested in aspects of the psyche that could not be attributed to an individual’s personal development but belonged to the deeper nonpersonal realms common to humankind. The collective unconscious is made up of archetypes, which Jung initially referred to as “complexes”—the “feeling-toned complexes” that affected the speed of a patient’s response to his word-association tests. In this primordial state they belong to what he called the psychoid realm, that is, they are not part of the psychic realm, which is made up of the personal unconscious and the conscious. Archetypes are not inherited ideas but potentialities—latent possibilities. Their origin remains forever obscure because they exist in a mysterious shadow realm of which we will never have direct knowledge, namely, the collective unconscious.

Jung described archetypes as an invisible crystal lattice shaping thoughts in the same way that a real crystal lattice refracts light. An arche type can be charged with energy, or “constellated,” by perceptions or thoughts from the personal unconscious and can thus be visualized through archetypal images or symbols. Thus the archetype can move from the psychoid realm to the conscious.

Archetypes are built into the mind. They are organizing principles enabling us to construct knowledge through an analysis of incoming perceptions. They influence our thoughts, feelings, and actions and determine whether a mind is sick or well.

Some years later Jung noted his “amazement that European and American men and women coming to me for psychological advice were producing in their dreams and fantasies symbols similar to, and often identical with, the symbols found in mystery religions of antiquity, in mythology, fairytales, and the apparently meaningless formulations of such esoteric cults as alchemy. Experience showed, moreover, that these symbols brought with them new energy and new life to the people to whom they came.”

In 1912 Jung published Symbols of Transformation, in which he began to develop in detail the concept of the collective unconscious. It was the final break with Freud. Almost until then, Jung professed a great devotion to Freud, his teacher. But the debate over the role of sexuality never faded away with Jung seeking a psychoanalytic theory of a more general—a more transpersonal—sort. As for Freud and his circle, they turned on Jung, damning him as an occultist. They reviewed his book harshly and he lost many friends and colleagues. Jung was disappointed but at least he was now absolutely free to indulge in the “images of my own unconscious.”

Remembering the totem of his boyhood, he now perceived it as “a little cloaked god of the ancient world, a Telesphoros such as stands on the monuments of Asklepios and reads to him from a scroll.” The only place he could have seen such a cloaked god in reality would have been in his father’s library, but there was certainly no such thing there. This was surely evidence that there were archaic components in the individual psyche.

A new psychology

What could these images mean? Where did they come from? Jung wanted to develop a psychological view that encompassed the metaphysical and the irrational. As to how to proceed, he was inspired by a passage from Goethe’s Faust referring to “continuity of culture and cultural history.” By looking into history he could find the elements that make up the mind.

He was also inspired by the writings of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. A generation of young turn-of-the-century German-educated intellectuals were attracted to Schopenhauer’s underlying philosophical message that optimism was naive. Only an outlook pervaded by pessimism could capture the essential nothingness of mankind, he wrote.

But Jung saw something more, particularly in Schopenhauer’s view of the mind—that representations visible to us emerged from an underlying invisible world, the abode of the ultimate physical reality. Surely this meant that mental or psychic energy could be traced to nodes of energy in the unconscious, namely archetypes.

From 1913, Jung began to take a new approach with his patients. Instead of applying a theoretical framework to his analytic sessions, he asked patients to report their dreams spontaneously, gently prodding them to interpret the dreams and helping them understand their own dream-images. He himself began to dream fantasies populated by violent dwarfs, savages bent on killing him, Biblical figures, and Egypto-Hellenic characters fraught with Gnostic coloration. He walked and talked with his dream figures. What was going on, he asked himself. Was this science and, if not, what was it? It was a riddle he had to crack.

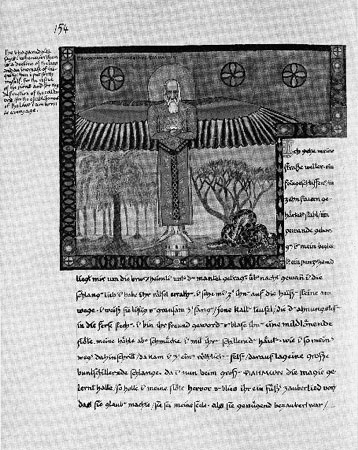

Eventually he concluded that the images in his dreams came from the collective unconscious and were transmitted to his conscious. In 1916 he transferred his extensive dream notes into what he called his Red Book, richly illustrated in the manner of a medieval manuscript. Jung permitted no one to see this book during his lifetime. When R.F.C. Hull, Jung’s longtime friend and translator, read it after Jung’s death he wrote, “Talk of Freud’s self analysis—Jung was a walking asylum in himself, as well as its head physician.”

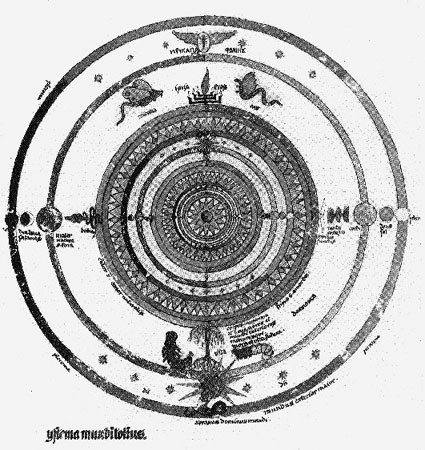

That same year Jung painted his first mandala (a diagram, usually based on a circle or square, with four symbolic objects symmetrically placed—and a key archetype and ancient symbolic device in cultures around the world). It flowed from him, he wrote, but he did not understand why he had painted it or what it meant. Art, it seemed, flowed from the unconscious. Convinced that his fantasies were spontaneous and self-created, he concluded that a mandala was a message that the conscious and unconscious had merged to become one: the Self was a whole. The appearance of a mandala in a dream signaled stability and inner peace, as Jung himself had come to feel.

The old man whom Jung called Philemon and with whom he walked and had long conversations. (Jung, Red Book [2009].)

Jung’s first mandala, drawn in 1916.

The next step was to bring these insights together. He called his new version of psychology “analytical psychology” to distinguish it from Freud’s psychoanalysis. But there was still a long way to go and many pieces of the puzzle to find.