2

Early Successes, Early Failures

THERE WAS something about Wolfgang Pauli. From early on in his career, colleagues couldn’t help noticing that whenever he entered a laboratory, equipment spontaneously broke down. The Pauli effect, as it became known, was obviously impossible; it had to be just a matter of coincidence. But nevertheless it happened again and again.

There was the time, in the 1920s, that there was a massive equipment breakdown in a laboratory at the University of Göttingen, in Germany. Early one afternoon, without apparent cause, a complicated apparatus for the study of atoms collapsed. Pauli wasn’t even in the country. He was in Switzerland. At last said his colleagues, relieved, here was clear proof it couldn’t be the Pauli effect. The professor in charge of the laboratory wrote a humorous letter to Pauli to tell him about it. The letter was sent to Pauli’s Zürich address. After a considerable delay, a letter arrived from Pauli with a Danish stamp on it. Pauli had been on his way to Copenhagen, he wrote. At the precise moment when the equipment broke down, his train had stopped for a few minutes at Göttingen station.

There were other things about Pauli too. He just happened to be one of the most brilliant physicists of his day. The great Einstein spoke of him as his successor. But Pauli was extremely modest and refused to participate in the feverish competitive scrum in which all the other physicists of his day pursued their research. Instead of publishing papers, he often revealed his insights simply in letters and discussions. When others published papers laying claim to the same insights, he didn’t bother to point out that he had discovered them first.

He was also famous for the excesses of his private life. While other physicists focused exclusively on their research, he’d spend his nights out on the town, hanging out in bars and cafés, getting drunk, carousing with singers and cabaret dancers, and getting into fights. He was never up before midday.

He didn’t look like a man who enjoyed the dark byways of life. In fact he always seemed rather staid. He was short and plump with a round, inscrutable face that colleagues said reminded them of a Buddha, and he had a famously sardonic sense of humor. But everyone agreed he was a wild character—though few people ever guessed that his life would fall so out of control that he would end up going into analysis with Carl Jung. Nor would anyone ever have imagined the effect this would have on his life and thinking.

Boyhood

Wolfgang Ernst Friedrich Pauli was born on April 25, 1900, in Vienna into a prestigious scientific family. His father, Wolfgang Josef Pauli, was a chemist at the University of Vienna and had an international reputation. Pauli’s godfather, from whom he took his middle name, was Ernst Mach, the famous physicist and philosopher.

On the occasion of Wolfgang’s baptism, Mach presented him with a goblet that he was to keep for the rest of his life. Many years later he wrote of the powerful influence that Mach exerted on him:

Among my books sits a somewhat dusty case containing an art nouveau silver goblet in which lies a card. Now there appears to me to rise from this goblet a serene, benevolent, and cheerful spirit [Mach] from the bearded age….

It so happened that my father, then intellectually completely under Mach’s influence, was very friendly with his family. Mach had affably expressed his willingness to play the role of my godfather. He was, no doubt, a stronger personality than was the Catholic priest. The result seems to be that, in this way, I was baptized as “Antimetaphysical” instead of Roman Catholic. In any case, the card rests in the goblet and, despite my greater spiritual transformations in later years, I still label myself as being of “Antimetaphysical ancestry.”

It is actually rather extraordinary that Pauli had a Catholic baptism, for his father came from a strongly Jewish family.

Pauli’s grandfather, Jacob Pascheles, had been a leading member of the Jewish community in Prague, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His house was a meeting place for a religious group who called themselves the Paulas. In his synagogue, he presided over many bar mitzvahs, including Franz Kafka’s. Pauli’s father studied medicine at Charles University in Prague and joined the staff of the University of Vienna at twenty-three, in 1892. He went on to establish himself as a renowned expert in the chemistry of proteins. Six years later the government granted him permission to change the family name to Pauli and a year after that he converted to Catholicism. This was not unusual for a Jewish-born academic; in the anti-Semitic environment of the Austro-Hungarian Empire it increased his chances of academic advancement considerably.

Soon after converting he married Bertha Camilla Schütz, who was also Catholic, though in fact her mother’s father was Jewish. She was highly intellectual. In the Vienna of the time, most women did not even attend high school. But Bertha was a correspondent for the influential liberal newspaper Neue Freie Presse for which she wrote theater reviews and historical essays.

Wolfgang was born a year after his parents’ marriage. His family called him “Wolfi.” His grandparents and aunts doted on him. He exhibited his love of precision from an early age. Once he was on a walk with his aunt, Erna. “See Wolfi,” she said, “we are on a bridge crossing the Danube Canal.” Four-year-old Wolfi set her straight: “No, Aunt Erna, this is the Vienna Canal which flows into the Danube Canal.”

Wolfi was seven when his sister Hertha Ernestina (also named after Mach) was born, in September 1906. (Later in life, perhaps to appear younger than she was, she was to list her birth date as 1908 or even 1909.) Pauli later confided to his second wife, Franca, that he had been jealous of the new baby and had felt rejected by his mother. But he seems to have got over it. In general theirs was a happy childhood. They grew up in a pleasant house on the outskirts of Vienna where they enjoyed exploring the surrounding woods and swimming in the Danube. Hertha recalled fondly how at Christmastime the family used to gather around the tree while Wolfi played “Silent Night” on the piano.

Young Wolfgang even tried to teach Hertha science. He showed her his collection of Jules Verne novels, precociously pointing out errors in the physics. When Wolfi was sixteen and Hertha was nine he decided to teach her astronomy. He informed his long-suffering sister that the so-called fixed stars were actually not fixed. In that case they must be falling, she replied. Pauli said no, but Hertha insisted. One can imagine the two arguing back and forth, the intellectual but blinkered young man and his equally stubborn sister.

It would have seemed there was not much point of contact between them, but in fact although they were never close, Hertha played an important role in Pauli’s mental life, as he discussed with Jung. In later years the two maintained an affectionate relationship. Writing in 1958, Hertha reminded Wolfgang of the Aunt Erna story and signed the card, “I embrace you. Always, Your Hertha.”

Pauli was ten when he entered the prestigious Döblinger Gymnasium in Vienna. He was popular with his fellow pupils, who remembered him as instigating many pranks. He had a talent for imitating professors. One, a particularly diminutive man, used to pop up unexpectedly amidst large groups of students. Pauli gave him the colorful and apt appelation das U-boot (the submarine). Four years later he had mastered geometry, calculus, and celestial mechanics, poring over books by the French poly-math Henri Poincaré.

Among the odd events in Pauli’s childhood, one of the oddest is his parent’s conversion, when he was eleven, from Catholicism to Protestantism. Whether or not there was much discussion of the subject, no letters or records remain to explain this decision or the effect it might have had on the young Pauli.

Then, when he was sixteen, his father’s mother made a rare visit. She revealed to him that his father’s name was not Pauli but Pascheles and that he was Jewish.

This is Pauli’s story. But the physicist Paul Ewald, who was the assistant to Arnold Sommerfeld—soon to become Pauli’s mentor—has a different version. He recalls that when he first saw Pauli, he thought immediately that he looked Jewish and told him so. Pauli denied it. Ewald advised him to go and look in the mirror. When Pauli went home for a visit he asked his mother and father about their backgrounds and in this way found out about his Jewish ancestry. Of course any discussion of this issue was almost certainly taboo in the Pauli family. To further obfuscate his Jewish origins, Wolfgang Sr. often went to such extremes as to enter into polemical exchanges over a certain discovery with a chemist named Pascheles—who was in fact himself.

Pauli never spoke of the events surrounding his father’s name change and his own discovery that he was Jewish. His widow, Franca, considered the change of name to be a family secret and became angry when interviewers mentioned it.

Nor did Hertha ever speak of it. In fact, taking the exact opposite stance to her brother, she insisted on speaking of herself as “half-Christian,” and went on to write books for children about the lives of Catholic saints.

For some years Pauli was not altogether happy to have discovered his Jewish ancestry. He found himself exposed to virulent anti-Semitism in Germany and Austria, fanned to even greater heights by rumors that the Great War (World War I) had been lost because of Communist and Jewish conspiracies.

One year after his mother’s death, in 1928, he decided to leave the Catholic church. Despite the fact that Judaism passes down the mother’s line and his sister Hertha always insisted she was half-Catholic, not half-Jewish, Wolfgang decided he was Jewish. Could he have been seeking a community, although he never did join one? In any case, a little over a decade later to assert his Jewishness in Germany or Austria would have been suicide. He was only able to fully come to terms with his Jewishness after lengthy analysis with Jung. Shortly after that, Nazi racial laws made it impossible for him—and for Hertha too—to avoid it. “With me everything is complicated,” Pauli later wrote.

Sadly, there is little personal correspondence on the subject—or on any other subject—among Pauli, his sister, his mother, and his father. There must have been letters and perhaps they are still out there. In the meantime, the closest we can get to the sort of man Pauli was is through information from those who knew him well.

At the gymnasium, Pauli quickly began to find his science classes too easy for him. By now he was receiving private tutoring in advanced physics from professors at the university and was soon discussing his ideas with them. He relieved his boredom by studying Einstein’s latest papers on the general theory of relativity, which he kept hidden under his desk, and was soon in full command of the theory.

Einstein discovered the general theory of relativity in 1915. It explores the motions of objects, from rocks to planets, stars and galaxies, and asserts that the world in which we live actually has not three but four dimensions—the usual length, breadth, and height, fused with time. The surface that light rays course over is a four-dimensional one, sculpted by the objects on it, in the same way that objects resting on a rubber sheet create wells. The indentations on this surface cause objects to roll toward each other and are experienced as gravity. Einstein’s general theory of relativity may have started out as one man’s view of the universe, but it was turning out to be the correct one. Scientists still refer to it as the most beautiful theory ever formulated.

At the time most physicists could not fully understand the theory’s elegant mathematics and wide-ranging concepts. Those who could realized that there was still a great deal of work to be done on it. This included clarifying and broadening aspects of Einstein’s mathematics, applying the theory to special cases—no mean task bearing in mind the abstruse mathematics—and widening it to include electricity. Pauli, at the tender age of seventeen, dived right in.

By this time Pauli was reading mathematics and physics books until two in the morning, like novels. Usually physicists read and reread textbooks, marking them with notes and underlinings. Most of Pauli’s books were unmarked. He only needed to read them once.

Pauli excelled in the courses that interested him—mathematics and physics—but had mediocre grades in nonscience subjects. Later in life he insisted that he had enjoyed them, especially Latin and Greek. In the annals of his school, Pauli’s class is remembered as the “class of geniuses,” and Pauli as the chief genius. Of the twenty-seven boys in Pauli’s class, two went on to win Nobel Prizes, while others made their name as actors, orchestra conductors, university professors, and leaders of industry.

Pauli graduated in 1918 with distinction and a mere two months later submitted a paper on relativity theory for publication. In it he clarified certain fine points of a particular version of Einstein’s theory, extended to include electricity (this had recently been proposed by the renowned mathematician and physicist Hermann Weyl in Zürich). In acknowledgment of his famous father, he signed this maiden paper Wolfgang Pauli Jr. It seemed the world was his oyster.

Meanwhile the Great War was coming to an end. Pauli was forced to undergo a medical examination to join the army and to his relief was found to have a weak heart, thus excusing him from conscription. He was passionately opposed to the war and the establishment, as classmates at the gymnasium recalled, and this only increased as the war went on.

Pauli was determined to pursue a career in physics, but as far as he could see Vienna was an intellectual desert, devoid of famous physicists. He decided to move to Munich, where the physicist Arnold Sommerfeld—a pioneer in the exciting field of quantum physics—was holding court.

According to one account, Pauli had already met Sommerfeld when he was a boy of twelve. The occasion was a lecture Sommerfeld was giving in Vienna and Pauli’s father obtained permission for his son to attend. Afterward Sommerfeld sought out the youngster and asked whether he had understood the lecture. Pauli replied that he had, except for one equation on the upper left-hand side of the blackboard. Sommerfeld looked up and replied, startled, “There I have indeed made a mistake.” True or not, the story attests to young Wolfgang’s reputation.

Pauli in Munich

The young man who arrived in Munich in October 1918 was a sensitive-looking eighteen-year-old with hooded eyes, full lips, and a rather sullen look to his face. He wore his dark wavy hair combed back. He was not particularly tall, about five foot five, but he carried himself with an air of confidence.

Munich was a city in chaos. Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey were on the verge of defeat and Allied armies—the Americans, English, and French—were poised to invade Bavaria (Munich was its capital city). The Allied blockade, exacerbated by two successive years of crop failures in the region, had resulted in starvation conditions. In 1917, in response to the huge losses of worker-soldiers, a radical minority of Socialists claimed that they had been double-crossed by imperialist capitalists. Inspired by the successful Russian revolution that same year, they agitated for a German Bolshevik revolution and the establishment of a Soviet-style Republic.

On November 7, 1918, a month after Pauli arrived, the Socialists organized a massive peace demonstration that was attended by over 50,000 people. With his strong socialist leanings, shaped by his mother’s politics, Pauli undoubtedly sympathized and perhaps even joined in.

The Socialists demanded the abdication of the Bavarian King, Ludwig III, and proclaimed a Soviet Republic. Armed soldiers and civilians occupied key points in the city. Informed of all this, the king calmly packed his family into his new Mercedes and drove away. Despite its name, the Soviet Republic was a liberal regime and enjoyed widespread support.

Arriving in this chaotic city, Pauli found lodgings near the university at Theresienstrasse 66. Some of the buildings on this broad tree-lined avenue still stand and have been returned to their original condition. Like them, number 66 was probably in the classical style, built of earth colored bricks, and four floors with large windows curved at the top. Pauli’s apartment was on the second floor, facing a courtyard at the back, which made the rent somewhat cheaper.

Turning left, Pauli would have strolled along Theresienstrasse and turned left again onto the Ludwigstrasse, a long straight boulevard, built in 1817 at the behest of King Ludwig I to reflect his love of Italy. Designed by an Italian architect, it resembles Rome’s magnificent Via de Corso. Another few steps would have brought him to the university. Crossing the boulevard he would reach the main entrance with its piazza and massive fountain. Now, as then, students congregate there.

Arnold Sommerfeld, Pauli’s new mentor, had studied at the University of Königsberg and immediately afterward had been called up for military service. Unlike his fellow academics, he revelled in it and ever after sported a magnificent turned-up waxed mustache, which more than made up for his short, squat build.

Sommerfeld, about 1916, shortly before Pauli came to study with him.

Pauli had come to sit at his feet. But after a brief conversation, Sommerfeld concluded that he had little to teach the young man. “I have with me a really astonishing specimen of the intellectual elite of Vienna in the young Pauli…a first year student!” he wrote to a colleague in Austria.

Sommerfeld was impressed with Pauli’s youthful paper on general relativity, which by now had been accepted for publication. It established Pauli as an expert in the field. He gave lectures on it at Sommerfeld’s institute and the paper had even come to Einstein’s attention. Pauli quickly wrote two more papers on relativity based on Weyl’s research. Weyl now went so far as to speak of him as a colleague. “I find it impossible to understand how you, being so young, managed to acquire the means of knowing and freedom of thought [necessary to understand relativity theory in its entirety],” he wrote to the young man.

At the time Sommerfeld was writing an article on relativity theory for the Encyclopaedia of the Mathematical Sciences, of which he was editor. Pauli attended a series of lectures he gave on the subject and offered some critical comments that intrigued Sommerfeld. So Sommerfeld asked him to co-author the article. In the end Sommerfeld became so heavily involved in his work on atomic physics that he turned the entire project over to Pauli.

The article was published in 1921 and was a tour de force. It was also published in book form and continues to this day to be an invaluable description of relativity theory. Einstein himself was impressed. “No one studying this mature, grandly conceived work would believe that the author is a man of twenty-one. One wonders what to admire most, the psychological understanding for the development of ideas, the sureness of mathematical deduction, the profound physical insight, the complete treatment of subject matters [or] the sureness of critical appraisal,” he wrote in a review. Not long afterward, the precocious Pauli was addressing letters to giants such as the British scientist Arthur Eddington. Eddington was exploring a part of the mathematics of the general theory of relativity that needed some firming up: how to connect points on the curved surface of its four-dimensional geometry. Pauli informed him that his results were at “the moment meaningless for physics.”

Around this time Einstein was to give an important lecture on relativity theory at the University of Berlin. Professors sat in the front row with lecturers and assistants behind them and the students at the back. Pauli, who was certainly not a professor and most probably still a student, chose to sit right in the middle of the front row dressed, according to one version of the story, in Tyrolean leather shorts. At the end of the lecture there was a hushed silence as the bearded professors in their starched white shirts and black ties decided who should ask the first question and what the order of precedence should be. Pauli sprang up, turned to face the audience, and announced with breathtaking chutzpah, “What Professor Einstein has just said is not really as stupid as it may have sounded.”

Generally Pauli preferred to study on his own and attended classes only when necessary. One was the laboratory course that he was forced to attend with a friend whom he referred to as his “laboratory fellow sufferer.” But he took an active role in the institute and was always on hand to discuss new developments in physics—in the afternoons, that is, for by now he had discovered the nightlife of Munich.

In the evenings, instead of turning left on Theresienstrasse to go to the university, Pauli would turn right. The road took him to the bohemian Schwabing district teeming with cafés, bars, beer gardens, and a huge number of cheap apartments. It was like a fusion of the Latin Quarter in Paris, where debates over the latest trends in art, music, and politics took place, with Montmartre, populated by the creators of these movements who generally lived in squalid conditions. Like the avant-garde scene in Paris there were publishing houses turning out new-wave literary magazines and satiric journals. It was the locus of radical experiments in art, politics, and sex. In Schwabing, anything went.

The area assimilated a spectrum of people. Before the war Vladimir Ilyich Lenin lived there while on the run from the tsar’s secret police and schemed with associates such as Rosa Luxemburg. Among other denizens were the writers Thomas Mann and Rainer Maria Rilke and the artists Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee. It was a place where up-and-coming artists aspired to achieve their first success. Among these was a young man who arrived in 1913 and made a living by selling his paintings of the area to tourists. He tried to fit into the bohemian culture, but never really did. Twenty years later Adolf Hitler, in his autobiography Mein Kampf (My Battle), recalled the “Schwabing decadents.”

Despite the upheavals in Munich, in October 1918 Schwabing was an island of calm. Café society was still bustling. Young Pauli, newly released from home, found it irresistibly attractive. He came to drink, to meet men and women, and perhaps to think about physics, while sitting at a table with a glass of wine or a cup of coffee. He had found the rhythm of his life.

Pauli spent longer and longer in Schwabing, though he was always careful to stay sober enough to be able to spend the small hours of the night working. It soon became impossible for him to make it to Sommerfeld’s morning lecture, which began at 9.00 a.m. Instead Pauli took to dropping in at noon to check the blackboard to see what the topic had been so he could work it out for himself.

Sommerfeld reprimanded him. “In order for you to become a genius I have to educate you,” he told him. “You have to come at eight o’clock in the morning.” Unusually in the stiff world of the German Herr Professor Doktor, he was prepared to tolerate erratic behavior if the student was undoubtedly brilliant. Touched that Sommerfeld took such personal interest in his well-being, Pauli began to turn up at 8.00 a.m., at least for a while.

Pauli was particularly gripped by Sommerfeld’s course on cutting-edge atomic physics, which focused on problems that the master himself was still struggling with. Fortunately for Pauli, the seminar took place once a week for two hours—in the evening.

After class a group of students often went to the café Annast, now part of the Hofgarten-Café, in the southernmost part of Ludwigstrasse, a short walk from the university’s main entrance. For scientists the attraction of the Annast was its marble-topped tables, which provided excellent surfaces for scribbling equations during animated conversations. According to one story, Sommerfeld was once stuck on a particular equation. When he left the café he forgot to erase his attempts to solve it. The next evening he returned and found that another customer had solved it for him.

War zone in Munich

A short three months after Pauli arrived in Munich, this idyllic world of pondering the universe came to an abrupt end. Suddenly Munich was in the grip of anarchy. The moderate Soviet Republic formed just a few months earlier had lost the support of the populace. It was not surprising. Every day Pauli would have seen people standing hungry in the streets, lining up for food in the snows of one of the worst winters on record. A host of political factions sprang up and with great speed coalesced into two groups: a moderate to extreme right-wing group and a left-wing communist one. Both sides had no trouble recruiting an army. Central Europe was swarming with thousands of armed, disgruntled, and starving soldiers looking for a fight. The situation was ominous. News traveled fast around Munich that there had been a gun fight in the Bavarian diet, and that two representatives had been killed.

For sizable periods of time the university was shut down. Cafés became classrooms for Pauli and his fellow students and teachers. They also offered front-row seats for the street fighting carried on by uniformed soldiers as well as local citizens. Sometimes it was difficult to tell one side from another. By April there was a second Soviet Republic.

But this second Soviet regime also failed to contend with the food and fuel crisis and in April 1919 total chaos descended on Munich. Having suppressed an attempted communist coup in Berlin, the federal government dispatched an army to Munich to put down the last vestiges of rebellion against it. They blockaded the city, exacerbating the already critical food and fuel shortages. The struggle boiled down to a confrontation between the Communist army of the Soviet Republic—the reds—and the army from Berlin—the whites. The Red Army had 15,000 soldiers. The whites had about 40,000 soldiers, committed to eradicate by any means the Communists who they saw as a threat to the new republic.

Even walking the streets was risky because the reds were arresting and summarily shooting anyone suspected of spreading discontent or who looked suspicious.

The backbone of the white army—the Berliners—was the Freikorps (Free Corps). This was made up of extreme right-wing fascist paramilitary units manned by combat-hardened ex-soldiers serving as mercenaries, former officers often with royal titles and students who had been too young to fight in the war and sought instant action against easy targets. They were financed privately by German industry and hated Communists. One unit of the Free Corps called itself the defender of the democratic spirit against Communists and Jews. From it emerged such staunch “defenders of democracy” as Rudolf Hess, who was to become Hitler’s deputy chancellor, and Ernst Röhm soon to command Hitler’s storm troopers. It was also to provide the start in life for the man who was to become Pauli’s closest colleague—Werner Heisenberg.

Preceded by a heavy artillery and mortar bombardment that created enormous damage and caused numerous civilian deaths, at the end of April the white army stormed Munich. Planes flew over, dropping leaflets telling people to surrender. There was heavy street fighting and massacres by both sides.

The fighting ended on May 8. Thousands of Red Army soldiers and civilian supporters had been killed—some estimates were as high as 20,000—in what became known as the white terror, wreaked mainly on the reds by the trigger-happy Free Corps. The white army estimated its losses at around 60. But the white terror was not yet over. People suspected of collaboration were summarily shot, stabbed, or beaten to death with rifle butts. Often they had been identified by spies who had infiltrated communist organizations, such as Corporal Hitler who had returned to decadent Schwabing. Munich, his favorite city, soon became the hot bed of his right-wing politics. The excesses of the Free Corps were so blatant that Lenin threatened to unleash Soviet forces on the area.

For Pauli, as for everyone, it must have been a traumatic and exciting time and also certainly dangerous. No doubt he wrote home about his experiences but sadly none of those letters remain. Perhaps Pauli’s father destroyed them when he fled Vienna in 1938. Pauli, himself, may have destroyed others when he left Europe in 1940.

Pauli meets Heisenberg

By 1920 peace had returned to the city. Pauli was now Sommerfeld’s deputy assistant. Among the students whose homework he had to correct was a young man called Werner Heisenberg.

Heisenberg was destined to become one of the great names in the history of physics. Even as a boy he was immensely competitive. He was not a natural athlete but trained with great determination and became an expert skier, runner, and Ping-Pong player. Like Pauli, he breezed through his classes at school and spent much of his time reading on his own, almost exclusively mathematics.

He had the look of “a simple farmboy with short, fair hair, clear blue eyes, and a charming expression,” his friends recalled. Heisenberg first encountered atomic physics at the age of eighteen, in 1919, reading Plato’s Timaeus while lying on a rooftop at the University of Munich during a break from his military duties as a member of the Free Corps, while rioting went on below him. (Five decades later Heisenberg was to recall those days as youthful fun, like “playing robbery [cops and robbers] and so on; it was nothing serious at all.” Perhaps. Or perhaps not.) Heisenberg was entranced with Plato’s description of atoms, visualized as geometrical solids. He knew this was now fantasy but was struck by the way in which the ancient Greek scientists were prepared to consider even the most unlikely speculations.

He had developed a keen interest in the theory of numbers and a year later entered the university. He had also tried studying Einstein’s relativity theory. The reigning power in the mathematics department, Professor Ferdinand von Lindemann, convinced that Heisenberg’s brush with relativity theory had spoiled his mind for a career in mathematics, rejected him outright. Sommerfeld, on the other hand, delighted with his enthusiasm and obvious brilliance, sent him straight to his graduate-level seminars, plunging him into advanced quantum physics.

Heisenberg and Pauli quickly struck up a friendship, cemented by their mutual passion for physics—although the two young men had diametrically opposite tastes when it came to what constituted a good time. Heisenberg recalled: “While I loved the daylight and spent as much of my free time as I could mountain-walking, swimming or cooking simple meals on the shore of one of the Bavarian lakes, Wolfgang was a typical night bird. He preferred the town, liked to spend his evenings in some old bar or café, and would then work on his physics through much of the night with great concentration and success.” It was often said that in Germany just after the war, in the pre-Hitler years of the Weimar Republic, there were two types of people: those who went in for night life and those who dedicated themselves to the youth movement. Pauli typified the former, Heisenberg the latter.

Whenever they were apart, they corresponded, though their letters were more like scientific articles as they bounced ideas off one another. Just as he had corrected Heisenberg’s homework in Münich, so Pauli continued to comment critically on Heisenberg’s ideas. “Pauli had a very strong influence on me,” Heisenberg recalled. “I mean Pauli was simply a strong personality…. He was extremely critical, I don’t know how frequently he told me, ‘You are a complete fool,’ and so on. That helped me a lot.”

“When I was young I believed I was the best formalist of my time,” Pauli said later in life, referring to his extraordinary understanding of mathematics and how to use it in solving problems in physics. Mathematics had served him well in his papers on relativity theory. Now Pauli was to apply his mathematical acumen to another puzzle that he was determined to crack and which formed the subject matter of his PhD thesis. It related to the great Danish physicist Niels Bohr and his seminal model of the “atom as universe.”

Niels Bohr and his theory of the atom

Bohr was another scientific prodigy. He arrived in England from Copenhagen in 1911, when he was twenty-six, and became fascinated by the work of Ernest Rutherford at Manchester University. Rutherford had just unraveled the structure of the atom in a series of experiments that suggested that the atom was made up of a nucleus with a positive charge, surrounded by enough negatively charged electrons to produce an electrically neutral atom.

In other words, it was a sort of miniature solar system. But the model was unstable. Science was out of step with nature.

Bohr set out to solve this problem. He showed that electrons in an atom could not revolve in just any orbit—like planets—but that only certain orbits were allowed. Given that atoms are generally stable, their planetary electrons cannot be pulled into the nucleus. If they did then the atom would collapse. Bohr interpreted the stability of atoms as proof that there had to be a lowest orbit. He found it by altering Newton’s theory of planetary motion using Planck’s constant.*

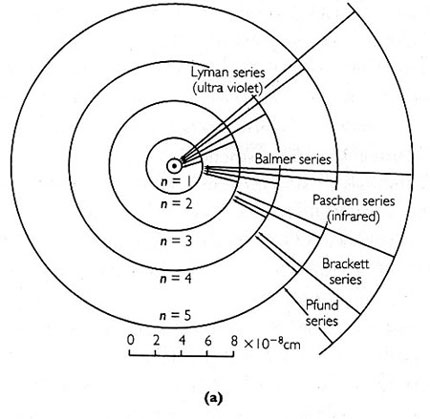

In his atomic “bookkeeping” Bohr assigned to each allowed orbit a whole number, which he called the “principal quantum number.” The lowest orbit was number one. As the principal quantum number increased, the orbits became closer and closer. Bohr called allowed orbits “stationary states.”

(a)

(a) This figure shows the hydrogen atom with its single orbital electron from Bohr’s theory of the atom, where n is the principal quantum number tagging the electron’s permitted orbits. When the electron moves from a higher to a lower orbit there is a burst of radiation, and the frequency of this emitted radiation can be measured as a spectral line. The Lyman series, Balmer series, etc. are series of spectral lines.

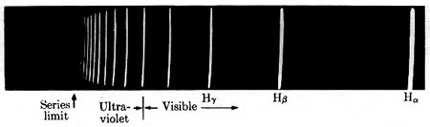

(b)

(b) This figure shows the Balmer series.

Since the late nineteenth century scientists had been aware that when light illuminated a collection of atoms, they emitted light in response. When the light the atoms emitted was passed through an instrument that separated its frequencies—a spectroscope—lines appeared. Dubbed spectral lines, these lines were unequally spaced and bunched up more and more as their frequency increased. Most strikingly the series of lines were different for each sort of atom. In fact, an atom’s spectral lines were its fingerprint, its DNA. Scientists had made a stab at writing equations to describe these lines, but there was no theory of the atom to explain the equations. Bohr’s was the first to succeed.

According to Bohr’s theory atoms emitted light when an electron moved from an upper to a lower orbit. The light that was emitted by an electron had the same frequency as a spectral line that had been observed. An oddity of the theory was that the electron’s transition from one orbit to another could not be visualized—it disappeared and appeared again like the Cheshire cat’s smile. In this sense the electron’s quantum jumps were discontinuous.

Bohr’s was a magnificent theory and it worked more than adequately. When applied to the hydrogen atom, the difference between the spectral lines observed in the laboratory and the spectral lines deduced from his theory was only 1 percent.

Scientists were impressed not only by its accuracy but also by its iconic visual imagery: the atom as a miniscule solar system with the electrons revolving in circular orbits around a central “sun,” or nucleus. It was a momentous fusion of large and small, of the universe and the atom, the macro-and microcosmos.

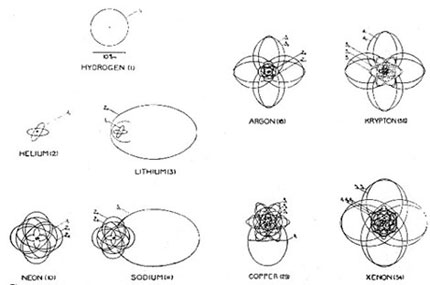

Bohr’s theory depicted the simplest element, hydrogen, as a single electron orbiting a positive charge—its nucleus. The atom had no total electrical charge; it was electrically neutral, just as atoms are in nature. Helium, the next element in the periodic table of the chemical elements, differs from hydrogen in that it has two electrons that orbit around a nucleus that has two units of positive electric charge. Because helium does not react chemically—it cannot bond with any other element—Bohr deduced that the innermost orbit needed to be filled up with two electrons. He went on to infer that the next orbit can take on eight electrons.

Atoms depicted according to Bohr’s atomic theory. (Kramers and Holst [1923]).

As another of the pioneers of atomic physics, Max Born, head of the Institute for Atomic Physics at the University of Göttingen, put it:

A remarkable and alluring result of Bohr’s atomic theory is the demonstration that the atom is a small planetary system…. The thought that the laws of the macrocosmos in the small reflect the terrestrial world obviously exercises a great magic on mankind’s mind; indeed its form is rooted in the superstition (which is as old as the history of thought) that the destiny of men could be read from the stars. The astrological mysticism has disappeared from science, but what remains is the endeavor toward the knowledge of the unity of the laws of the world.

Pauli’s work on Bohr’s theory

No one had attempted to apply the Bohr theory to anything more complex than the hydrogen atom. Pauli set out to do so.

He began the year after he arrived in Munich and decided to apply Bohr’s theory to the next simplest atomic system to the hydrogen atom, that is, two protons orbited by a single electron—the hydrogen-molecule ion, H+2. The mathematics he had to grapple with was extremely complex. The problem gnawed at him. It took over his life. He ended up thinking about it night and day.

The last thing Pauli wanted was to disprove Bohr’s iconic model. But after two years of working on the problem he had to conclude that he had proved beyond doubt that Bohr’s theory could not produce the necessary orbits—or “stationary states”—for a stable H+2 ion. When he applied Bohr’s theory, he discovered that a small disturbance to the electron orbiting the two protons would make it fly away from them. But that couldn’t be right because stable H+2 ions had already been found in the laboratory. This could only mean that there was something fundamentally wrong with Bohr’s model—not at all the result Pauli had hoped for.

Pauli was deeply discouraged. But Sommerfeld praised his mathematical skill and thoroughness. Heisenberg considered Pauli’s result ominous. “In some way this was the first moment when really this confidence [in Bohr’s theory] was shaken,” he said.

Then Pauli received an invitation from Max Born. Born had done important work in electromagnetic theory, relativity, acoustics, crystallography, and most recently atomic physics. He was highly impressed with Pauli’s mathematical skills and invited him to spend six months at the institute. Pauli accepted.

“W. Pauli is now my assistant; he is amazingly intelligent and very able. At the same time he is very human and, for a 21-year-old, normal, gay, and childlike,” Born wrote to Einstein. By Pauli’s own account, he was actually rather miserable. Born and Pauli applied Pauli’s mathematical methods to the helium atom (He)—two electrons orbiting a nucleus. But Bohr’s theory failed here, too. It horrified Pauli that all his work seemed to result only in undermining this iconic theory. As far as he was concerned, it was he who had failed, not the theory. This failure loomed over him and grew into a general sense of gloom.

Despite Born’s presumption of his “gaiety,” he had also noted that Pauli “cannot bear life in a small city.” Nor was Pauli particularly enamored of working with Born. While Born was neat and well organized, Pauli was not. Born was an early riser, Pauli far from that, especially after late nights working. Born often had to send someone to Pauli’s apartment at 10:30 in the morning to awake him for his 11 o’clock lecture. Born recalled: “Although a place like Göttingen is accustomed to all kinds of strange people, Pauli’s neighbors were worried to watch him sitting at his desk, rocking slowly like a praying Buddha, until the small hours of the morning.”

Pauli also did not appreciate Born’s overly heavy mathematical style of physics. He felt that the time was not yet ripe for such a rigorous approach. For him adroit guesswork backed up by mathematics was the best way to proceed.

Three months after his arrival in Göttingen, Pauli was offered a position as assistant to Wilhelm Lenz, professor of physics at the newly established University of Hamburg. He immediately accepted.

When Pauli had first arrived in Göttingen, Born lamented to Einstein that, “Young Pauli is very stimulating—I shall never get another assistant as good.” In fact he did. Two years later Heisenberg appeared. Born wrote to Einstein, “He is easily as gifted as Pauli, but has a more pleasing personality. He also plays the piano very well.” The two tried again to tackle the helium atom using other mathematical approaches to solar system models and failed. “All existing He[lium]-models are false, as is the entire atomic physics,” was Heisenberg’s bleak assessment.

Pauli meets Bohr

In June 1922 Pauli returned to Göttingen to attend a Bohr-Festspiele (Bohr festival) Born had organized to launch his new Institute for Atomic Physics. Sommerfeld, too, was there along with Heisenberg.

“A new phase of my scientific life began when I met Niels Bohr personally for the first time,” Pauli later recalled. For both Pauli and Heisenberg it was hugely inspiring to meet this giant of physics.

Fifty years later Heisenberg still remembered the mesmerizing way in which Bohr presented his theory. He “chose his words much more carefully than Sommerfeld usually did. And each one of his carefully formulated sentences revealed a long chain of underlying thoughts, of philosophical reflections, hinted at but never fully expressed. I found this approach highly exciting…. We could clearly sense that he had reached his results not so much by calculation and demonstration as by intuition and inspiration, and that he found it difficult to justify his findings before Göttingen’s famous school of mathematics.” As physicists used to say, at Munich and Göttingen you learned to calculate, but at Bohr’s center at Copenhagen you learned how to think. This was certainly the case for Heisenberg and Pauli.

One of the ways in which Bohr’s original theory had been developed was to allow electrons to move in three dimensions, transforming the orbits into shells. In his lecture he described his latest work, which concerned how the electrons in an atom distributed themselves. The essence of the problem was the way in which atoms were built up, beginning with the hydrogen atom with its single electron. Understanding this would be a first step to explaining why the periodic table of chemical elements fell into place as it did, a key problem that everyone recognized needed to be cracked.

Examining the experimental data, Bohr proposed that there were two electrons in the first shell, eight in the second, and so on. He was then able to deduce these numbers from a series, each of which could be obtained from the formula 2n2, where n is the principal quantum number for the shell (in Bohr’s original model, n was the principal quantum number for an orbit, but orbits had now been replaced by shells). If n is 1 then the total number of electrons in the first shell is 2; if n is 2, the number of electrons in the second shell is 8; the next shell becomes 18, and so on. The assembled scientists discussed this series of numbers with great intensity. But as they listened, both Heisenberg and Pauli realized that there was no basis in fact to what Bohr referred to as the “building up principle.” As for Sommerfeld, he dismissed Bohr’s reasoning as “somewhat Kabbalistic.”

Bohr’s reasoning also failed to answer the problem of why every electron did not simply drop into the lowest shell—at least for atoms other than hydrogen and helium.

Pauli and Heisenberg argued fiercely with Bohr, who was impressed with their knowledge of physics and their uninhibited critical give-and-take. Bohr was also impressed with Pauli’s work on the H+2 ion and the helium atom, although in each case he had come up with a result that seemed to disprove Bohr’s own theory. Discussions continued into the evening in coffeehouses and on walks. Heisenberg complained that no one went to bed before 1 a.m. Pauli, of course, was in his element.

After the meeting, Bohr invited Pauli to visit Copenhagen for a year, from September 1922, to help in his research. Pauli replied rather arrogantly, “I hardly think that the scientific demands which you will make on me will cause me any difficulty, but the learning of a foreign language like Danish far exceeds my abilities.” He accepted nonetheless.

In Copenhagen Bohr set a problem that was to haunt Pauli for years and was one of the factors that led to his breakdown. The problem was on the anomalous Zeeman effect. To understand it, we have to go back to Pauli’s old mentor at Munich, Arnold Sommerfeld, and his work on the structure of spectral lines.

The discovery of 137

According to Bohr’s theory, when an electron drops from a higher to a lower orbit it emits light, which is recorded in the laboratory as a spectral line. Bohr was able to work out equations for these spectral lines that could be compared with the data obtained in the laboratory.

By 1915 scientists had more accurate spectroscopes that enabled them to make closer inspection of spectral lines. This revealed that many of the individual lines were in turn made up of several more closely spaced lines: they were said to have a “fine structure.” Certain spectral lines also split into several lines or “multiplets” when the atom was placed near a magnet, but the fine structure was always there. “It was given by Nature herself without our agency,” Sommerfeld wrote.

Sommerfeld’s primary contribution to atomic physics was his work on the fine structure problem. His brainwave was to apply relativity theory to Bohr’s theory, changing the mass of the electron following Einstein’s famous equation E = mc2. The result was astounding: an extra term appeared in Bohr’s equation for a single spectral line. This extra term made it possible to predict that certain lines would actually split and reveal their fine structure.

Sommerfeld called the quantity that set the distance between the split spectral lines in this extra term the “fine structure constant” and designated it with the Greek letter  (alpha). His equation was:

(alpha). His equation was:

The fine structure constant is made of three fundamental constants: the charge of the electron e (1.60 × 10-19 coulombs—a coulomb is the unit of electric charge); the speed of light c (3 × 108 meters/second), which defines relativity theory; Planck’s constant h (6.63 × 10-34 Joule-seconds), which defines quantum theory and determines the size of the grains into which the microscopic world is partitioned, be it grains of energy, mass, or even of space itself.  (pi) is the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter (3.141529). The constants e, c, and h had already been measured. Thus the discovery of the fine structure constant was a step toward the great goal of finding a theory that would unite the domains of relativity and quantum theory, the large and the small, the macrocosm and the microcosm.

(pi) is the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter (3.141529). The constants e, c, and h had already been measured. Thus the discovery of the fine structure constant was a step toward the great goal of finding a theory that would unite the domains of relativity and quantum theory, the large and the small, the macrocosm and the microcosm.

There was one extraordinary feature of the fine structure constant. The three fundamental constants that make it up have dimensions—such as space and time—and therefore depend on the units in which they are measured, whether metric, imperial, or some other. So although they would certainly play an essential part in a relativity or quantum theory formulated by physicists on a planet in another galaxy, they might not have precisely the same values as they have on earth.

But when they come together to form the fine structure constant, something extraordinary happens. All of their units cancel out and as a result the fine structure constant is a pure number without any dimensions. No matter what the number system this will always be true. Sommerfeld calculated it as 0.00729—a rather unexciting way of expressing such a momentous result.

Sommerfeld’s extension of relativity into atomic physics was “a revelation,” wrote Einstein. Bohr wrote to Sommerfeld, “I do not believe ever to have read anything with more joy than your beautiful work.”

A dimensionless number of such fundamental importance had never before appeared in physics. Of course dimensionless numbers had always been present in equations, but never one that was deduced from fundamental constants of nature. Scientists later realized that if the numerical value of the fine structure constant were to differ by a mere 4 percent, almost all carbon and oxygen would be destroyed in every star in the universe and life on our planet would not exist or would be dramatically different. The fine structure constant was one of the primal numbers that bound all existence together.

One of the many puzzles that arose was the question of why spectral lines of atoms split when they were placed in a magnetic field, between the pole faces of a magnet. Back in the mid-nineteenth century the British scientist Michael Faraday had identified the phenomenon but his equipment was not yet precise enough to enable him to pursue it.

In 1896 Pieter Zeeman, a young Dutch researcher at the University of Leiden, was looking for a research problem. Going through physics journals from decades earlier, Zeeman came upon Faraday’s ruminations over the behavior of atoms in magnetic fields. With the more precise equipment at his disposal, he succeeded in discovering the additional split spectral lines caused by a magnetic field. This was dubbed the Zeeman effect.

Two years later all was not well again. When Zeeman tried using a weaker magnetic field, he found that the spectral lines split into different patterns of even more lines—multiplets. This peculiar situation became known as the “anomalous Zeeman effect.”

The puzzle that Bohr set to Pauli was to find an equation that described this behavior. The effect existed; it had been identified. Therefore it must be possible to deduce an equation from Bohr’s iconic theory of the way atoms worked—electrons revolving like planets in small solar systems. Despite its shortcomings Bohr’s theory offered the only means to deal with problems of atomic physics. Perhaps it could be modified to suit the one at hand.

Day and night Pauli thought about it. He calculated and calculated, he tried this approach and that approach, and eventually he fell into a fit of despair. Everything had been going so well. The boy genius’s triumphant entry into Munich had been heralded by an important paper on relativity theory and two more quickly followed. Even Einstein had been impressed. But ever since it had been nothing but one failure after another: “A colleague who met me strolling rather aimlessly in the beautiful streets of Copenhagen said to me in a friendly manner, ‘You look very unhappy,’ whereupon I answered angrily, ‘How can one look happy when he is thinking about the anomalous Zeeman effect?’”

There had to be a way. But how?