3

The Philosopher’s Stone

Jung’s analytical psychology: The four function types

MEANWHILE, in Zürich, Carl Jung was establishing a vocabulary and framework for his budding new field of analytical psychology. In 1921 he published his seminal book on the subject, Psychological Types.

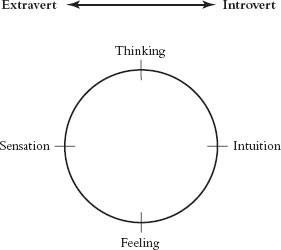

In this he argued, based on his vast experience with patients, that there were two opposing modes of being that determined and limited a person’s reaction to the world and to himself—introversion and extraversion. In Jung’s initial definition, introversion is a turning inward from an object, while extraversion is the reverse. Jung was the first to coin these two terms, which have since become common currency. He then broke these two categories down further and proposed four basic functions or function-types: thinking, feeling, sensation, and intuition. He was intrigued that there appeared to be four function types rather than three or some other number. But for the moment he set the problem aside.

Jung defined what he called the four orienting functions of consciousness thus: thinking leads to logical conclusions; feeling is a means to establish a subjective criterion of acceptance or rejection; sensation directs one’s attention outside oneself and is caused by conscious perception through the sense organs. As for intuition, it is somewhat like sensation but there is no cause for directing one’s attention. Rather, there is a hunch, an inspiration, or gut feeling. Conclusions surface not by logical means but as if bursting out of nowhere, such as in suddenly realizing how to solve a problem when you are not consciously thinking about it.

The two opposing modes of being and four function types.

Jung then divided these four functions into two groups of two: thinking and feeling, which are to do with rationality and logic; and intuition and sensation, which he classified as irrational, outside of reason. Besides his clinical experience, Jung drew upon his knowledge of Eastern and Western religions and of myths, philosophy, and literature to support his theory of types. In particular, he drew on the notion of pairs of opposites such as evil/good, darkness/light, matter/spirit, which he saw as emerging from deepest history—before Christianity, the Hebrews, the Egyptians, and the Chinese—and providing the energy for creativity and for life itself.

The extent to which these four functions predominate in an individual, Jung argued, gives each person a mode of being. Specifically, thinking types direct their mental energy toward thought at the expense of feeling, which disturbs the flow of logic; feeling types are governed by their feelings. Similarly, to understand a situation with one’s senses—by sensation—requires concentration and focus, whereas trying to intuit a situation requires taking in its totality and flitting around it. These are opposites because no one can do both at once.

When one function is particularly dominant, the opposite one may lapse into the unconscious and return to its earlier archaic state. The energy generated by this inferior function drains into the conscious and produces fantasies, sometimes creating neuroses. One goal of Jungian psychology is to retrieve and develop these inferior functions. Jung was careful to point out that no one is strictly a thinking or feeling type. We are all combinations of the two types and the four functions. Our personality, or psychology, results from a struggle among these opposites for equilibrium.

At this time Jung had also begun to study the Gnostic writers, spurred on by his interest in myths. He was aware that Freud had derived his influential myth of the primal father and its effect on the superego from the Gnostic motifs of sexuality and Yahweh, which dated back to ancient Egypt and early Judaism. The Gnostics speculated that the content and images of the primal world of the unconscious might be clues to uncovering the mysteries of the universe. But at first Jung could find little relevance in their writings, nor could he find any historical bridge between Gnosticism and the contemporary world.

And still he dreamed. What could these images mean? Where did they come from?

Among the most vivid of his dreams were two in which he found himself in a huge manor house. In one he wanders from room to room and eventually ends up in a spacious library full of books from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The engravings on the books are unfamiliar and the illustrations include curious symbols. In the second he is in a horse-drawn coach that enters a courtyard. Then the gates slam shut and a coachman screams that they are trapped in the seventeenth century. His efforts to explain this dream sent him delving into books on history, religion, and philosophy, particularly of that period.

Meanwhile, he was shaping his own method of treating neuroses. Freud interpreted a boy’s incestuous desires for his mother as a literal return to the womb, to a state free from responsibility and decisions. Jung preferred to see the positive side, as breaking down the bond between mother and son and thus freeing psychic energy to be transferred to other archetypal components. In this way he removed the purely sexual connotation of incest, choosing rather to explore it in terms of archetypal metaphors and symbols. By now Zürich had become the center for this developing technique of analysis, Jung’s “analytical psychology.”

Alchemy

Back in 1914, Jung had come across a book by Viennese psychologist Herbert Silberer, who was part of Freud’s circle. In Problems of Mysticism and Its Symbolism, Silberer discussed whether there might be a relationship between the imagery in alchemical texts, the imagery experienced by patients in the mental state between dreaming and waking, and Freud’s analysis of dreams. At first Jung was fascinated and corresponded with him. He was looking for something deeper than Silberer—to understand the imagery that had never been conscious, the imagery in the deep or collective unconscious. But he soon concluded that alchemy was “off the beaten track and rather silly.”

Nevertheless Jung began collecting ancient alchemical texts. Then, in 1928, his friend Richard Wilhelm sent him a copy of his translation of the thousand-year-old Taoist-alchemical text The Secret of the Golden Flower.

At first The Secret of the Golden Flower did not seem to make any sense. But Jung was intrigued. Silberer’s book came to mind and he suddenly realized that although he had appreciated what Silberer was suggesting, he had not understood how to interpret the alchemical texts Silberer used. For the next two years Jung pored over alchemical texts and began to find more and more passages that he could understand. Then he had a revelation. “I realized that alchemists were talking in symbols—those old acquaintances of mine,” he wrote. It was the symbols not the text that were the essence. He decided to learn alchemy from the ground up and then return to Silberer’s and Wilhelm’s books.

Alchemy was conceived of as a means toward understanding the “great chain of being”—in other words, all life—stretching from our “corruptible world” to heaven. There were two sorts of alchemist. Scientific alchemists, the forerunners of modern chemists and metallurgists, searched for ways to transmute base metals into gold and jealously guarded their recipes. The mystical school of alchemy, however, interpreted transmutation as a spiritual path to redemption. They considered their laboratory experiments to be part of an inner process of maturing while nurturing a contemplative attitude. Alchemy embraced the teachings of the Greek philosopher Proclus as well as mystery religions such as Zoroastrianism and the ancient cults of Isis, Mitre, Cybel, and Sol Invictus.

Alchemists postulated that everything, even metals, was made up of the four elements—earth, water, air, and fire—and that these four elements could be transformed one into another. They called this process of transformation the “circle” or the “rotation of the elements.” The goal of alchemy was to bring about a union of all four elements to produce the mystical fifth element—the quintessence, or the legendary “philosopher’s stone,” the ultimate state of enlightenment. In alchemical books the four elements were represented by the four sides of a square. The philosopher’s stone—referred to as the one, the perfection, and imbued with the power both to transmute base metals to gold and to transform man into the illumined philosopher—is represented by a circle. It is the light hidden in dark matter; it combines creative divine wisdom and creative power. Christians sometimes identified it with Christ, while Buddhists symbolized it as the jewel in the lotus.

The first step in creating the philosopher’s stone was to obtain the prima materia, the basic material from which all metals are derived, “philosophical mercury”—Mercurius, known also by his Greek name, Hermes, symbolizing the universal agent of transformation as opposed to the vulgar physical mercury of the scientific alchemists. Mercurius is present throughout the process of transformation from its dark beginnings (as prima materia) to its triumphant end (as the philosopher’s stone). In this way Mercurius participates in both the dark and light worlds.

Prima materia, in its turn, comes out of the union of male—sulphur (the hot, dry, active principle)—and female—argent-vive, or mercury (the cold, moist, receptive principle). In alchemical philosophy this union symbolized the wedding of man and woman, the coniunctio of King Sol and Queen Luna (sulphur and argent-vive). Sol (the Sun) is the male force of the universe, creative will. Luna (the Moon) represents the receptive female force, wisdom. The material world is generated out of sulphur (fire and air) and argent-vive (earth and water), that is, out of the four elements. Thus the conjunction of all these gives rise to the world of mysticism.

Alchemy and psychology

As he read more and more deeply in alchemical works, Jung realized that he had discovered the “historical counterpart of [his] psychology of the unconscious.” Alchemy provided an unbroken historical link between the ancient Gnostics of first-century B.C. and the contemporary world. Its roots went back through Gnostic writings to Plato, Pythagoras, texts attributed to the magus Hermes Trismegistus of ancient Egypt (referred to as Moses in the Kabbalah), and ancient creation myths such as the Enuma Elish from seventh-century-B.C. Babylonia.

The Hermetic view was that after the fall humankind had divided into two states, the male and the female. The alchemical wedding returns man to the original Adamic state—to Adam—thus reconciling opposing forces and creating the highest wisdom, which is the philosopher’s stone. The alchemical wedding releases the world-soul—the soul of the whole world—which had lain dormant until this reconciliation and which unites the souls of individuals and also of the planets, which are living entities and not merely matter.

Thus Jung finally understood the meaning of his two dreams about being trapped in the seventeenth century, the period when alchemy was at its height. Hereafter primordial dream images, which he saw as visual symbols of archetypes, began to play a central role in Jung’s analytical method, along with ancient myths and religion.

Jung’s associates warned him that he might be considered a charlatan if he dabbled in alchemy. If a scholar of Wilhelm’s standing could publish a book on alchemy, Jung replied, then so could he. Furthermore, he was convinced that alchemical imagery and notions of transformation could provide another approach to understanding the psyche.

So Jung set to work to incorporate alchemy into his analytical psychology. One of his patients, Aniela Jaffé, later to become his personal secretary and collaborator, recalled a particularly startling yet productive analytic session. She was describing her problems with her mother when Jung abruptly cut her off with the words, “Don’t waste your time.” He went to his bookcase and took down the Mutus Liber, an alchemical book from the seventeenth century that contained only images, no text, and they spent the rest of the session discussing the images. Looking back on this and similar sessions in later years, she recorded that they had a more lasting influence on her than any of those spent in conventional therapy.

Thus by incorporating alchemy into his analytic psychology, Jung began to evolve a dramatic new way to understand the unconscious.