11

Synchronicity

The riddle of the electron

IN ANCIENT TIMES, matter was thought of as being the mother of all things. From this alchemists derived the notion of the prima materia (prime matter), which is uncreated and which therefore contains the attributes of God. In modern physics, conversely, matter has become entirely ephemeral in that it can be created and destroyed, as in the spontaneous creation and annihilation of pairs of antiparticles and particles. One of these antiparticles is the antiparticle of the electron, the positron, which possesses exactly the same properties as the electron except that it has a positive instead of a negative charge. When particle and antiparticle come together they disintegrate in a flash of light. In 1932 the positron—first predicted by Paul Dirac in the famous Dirac equation—had been discovered in the laboratory.

This supported Pauli’s view that there was no foundation for a view of life based on the pre-eminence of matter. Einstein symbolized his discovery that mass—that is, matter—and energy were equivalent in the equation E = mc2. Here solid mass is replaced by energy, which has no form. Energy is indestructible and outside of time, and as a result the total quantity of energy always remains the same. This is known as the law of conservation of energy. But one of the astounding results of relativity theory is that there is no law of conservation of mass.

Although energy is timeless, it appears in space and time in particular ways. In quantum physics the energy of a spectral line is proportional to its frequency, that is, the number of oscillations of light per time interval. Imagine you have isolated a single hydrogen atom whose lone electron occupies a stationary state above its ground state or lowest level. The atom is said to be in an excited state. In nature the preferred mode of being is equilibrium. The lone electron will eventually drop to its lowest level and emit light. This can be measured in the laboratory as a spectral line. Observing the atom over a long time results in a very narrow spectral line with a precisely determined energy. Information has been lost, however, because the scientist doesn’t know when the electron made its transition to the lowest level. Conversely, observing the atom in its excited state over a short time results in a broad spectral line whose precise energy cannot be determined—there is a spread of energies. But at least now the scientist knows the precise time at which the transition to the lowest level was made.

In other words, the more precisely you know the energy of a spectral line which sparks when an electron jumps from a higher to a lower orbit in an atom, the less precisely you can measure the time that it took to make the transition. There is an uncertainty relationship between energy and time, similar to the one between position and momentum that Heisenberg discovered.

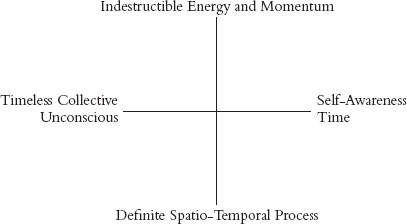

Pauli referred to these two axes—energy and time—as “Indestructible energy and momentum” versus “Definite Spatio-Temporal Process” and saw them as complementary aspects of reality, in that a little of each is always present to a greater or lesser degree.

Pauli’s dreams had convinced him that there was a relationship between the frequency of spectral lines, particularly doublets, and the tension between pairs of opposites such as conscious and unconscious. Energy, which is outside of time, is complementary to processes occurring at definite intervals of space and time, and similarly there is a complementarity between the archetypal psyche which exists throughout time (the timeless collective unconscious) and our own individual conscious psyche, or ego, which exists over specific time intervals in our daily life. (He abbreviated the ego as “self-awareness” and the archetypal psyche as “time.”)

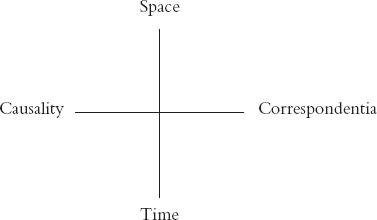

Pauli laid all this out as a mandala in the shape of a cross. From this he deduced that the laws of physics are a projection onto the psyche (the conscious/unconscious) of an archetypal association of ideas arising from the collective unconscious: in other words, a clash of the four opposing concepts that he depicts at opposite ends of the two crosses.

Pauli’s preliminary mandala showing the collective unconscious and events in space and time.

The mandala lays out the fundamental complementarity at the heart of both psychology and quantum physics. Bohr had spoken of “the general difficulty in the formation of human ideas, inherent in the distinction between subject and object.” In quantum physics, the person making the measurement and the measuring apparatus affect whatever is being measured. Similarly in psychology, the psychologist can never really know the unconscious through psychoanalysis. He must always interpret the results of his questions and inevitably he himself will affect his conclusions. Data can never be understood except through the lens of a theory.

In 1948, around the time of the spring equinox, Pauli had two dreams. For him the equinoxes, he said, were times of “relative psychic instability, which can manifest itself both negatively and positively (creatively).” The dreams that arose at those times were always of particular significance.

His dreams were full of mathematical symbols. In one of them i appears, i being the square root of –1:  . i is an “imaginary number” because it is not one of the numbers we use in daily life—the so-called real numbers. Nevertheless, i often functions to unify complicated formulas by making them more compact.

. i is an “imaginary number” because it is not one of the numbers we use in daily life—the so-called real numbers. Nevertheless, i often functions to unify complicated formulas by making them more compact.

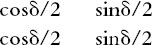

In one of his dreams a woman brings Pauli a bird. It lays an egg that then divides into two eggs. Then he notices that he has another egg in his hand, which makes three. Suddenly the egg in his hand divides into two. He now has four; a quaternity has appeared. Before his eyes the four eggs morph into four mathematical symbols, in two groups, side by side:

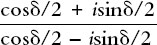

“cos” (cosine) and “sin” (sine) are quantities from trigonometry (a form of mathematics that deals with triangles) while “ “(delta) is the angle formed by two sides of a triangle. These four symbols coalesce into a single expression, unified by the symbol i:

“(delta) is the angle formed by two sides of a triangle. These four symbols coalesce into a single expression, unified by the symbol i:

This expression is well known to mathematicians.

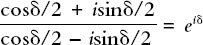

In his dream he turns this expression into an equation:

where e, the “base of natural logarithms,” has a numerical value of 2.71828…(referred to as an “irrational” number in that the group of numbers “1828” never repeats); and  has a magnitude of 1. The insertion of i into these sets of four has created a unity.

has a magnitude of 1. The insertion of i into these sets of four has created a unity.

Reflecting on the eggs in his dream, Pauli realized that it was precisely what Maria Prophetissa, the early practitioner of alchemy, had described some seventeen centuries earlier: “One becomes two, two becomes three, and out of the third comes the One as the fourth.” This transformation, he noticed, “typically comes about for me through mathematics.”

Pauli’s interpretation of this whole dream is far removed from mathematics. Describing it to Jung, he explains that  is a number that always lies on a circle of radius 1. Through the power of the mathematical symbol i, a mandala has appeared in the form of a circle. In Pauli’s dream i “has the irrational function of uniting pairs of opposites”—the cosine and sine functions arranged in two groups of opposites—“and thus producing wholeness.” But e too is “irrational,” it is an irrational number. This shows, he says, that mathematics “is a symbolic description [of nature] par excellence.” Mathematical symbols are the perfect way to unite and represent counterintuitive features of the quantum world, such as the wave-particle duality, which can never be visualized.

is a number that always lies on a circle of radius 1. Through the power of the mathematical symbol i, a mandala has appeared in the form of a circle. In Pauli’s dream i “has the irrational function of uniting pairs of opposites”—the cosine and sine functions arranged in two groups of opposites—“and thus producing wholeness.” But e too is “irrational,” it is an irrational number. This shows, he says, that mathematics “is a symbolic description [of nature] par excellence.” Mathematical symbols are the perfect way to unite and represent counterintuitive features of the quantum world, such as the wave-particle duality, which can never be visualized.

Reflecting further, Pauli suggests that the successive splittings of the eggs are analogous to the splitting of spectral lines. When one examines the fine structure of a spectral line, the spectroscope shows that what appears to be a single line is actually two and that the spacing between the two lines is defined by the number 137. In that case, could it be, he wondered, that two was the primal number in physics, not four? In both physics and psychology there were complementary opposites suggesting that two was the predominant number in the psyche as well. But four—the quaternity—had appeared in his dreams, signifying the wholeness of the material world and our conscious knowledge of it as well as the unconscious. Pauli’s discovery of the fourth quantum number indicated precisely the need for this wholeness and therefore, although it was surprising at first, it should have been expected all along, given that four was the archetype of completeness.

i, the square root of –1, which unifies the various elements in Pauli’s dream, also appears in Schrödinger’s wave function (the solution to Schrödinger’s equation). Schrödinger’s wave function depends on i and unifies the wave and particle properties of matter as well as being the essential ingredient in making measurements in quantum physics.

This dream reinforced Pauli’s conviction that quantum physics ought somehow to form part of a more comprehensive, bigger world picture. It referred only to phenomena that could be described by mathematics and focused its attention on what could be measured in the laboratory, and did not take into account notions such as consciousness. It dealt only with the realm of inanimate matter and thus the anima had been excluded. This excluding of the anima was exactly what Kepler had done when he set about developing modern physics and why Pauli eventually came to side with Fludd.

Parallels and coincidences

Any discussion of dreams, physics, and psychology, Jung believed, required examining the notion of time, and in particular “synchronicity,” a concept which he had been exploring since his early fascination with parapsychological phenomena as a medical student.

In the following years Jung had read deeply in mythology and alchemy where he developed the notion of “one world”—the unus mundus. If there were one world, he reasoned, surely there should also be one mind, which he identified as the collective unconscious of humankind.

When he consulted the I Ching, the advice appeared to be called forth by the moment. If he asked the same question a second time—at a different moment—the advice might be quite different. If the I Ching’s answers had any meaning at all, then how did “the connection between the psychic and physical sequence of events come about?” he wondered.

In the 1920s Jung began to look seriously into parallels between out-of-body occurrences and mental states. One notable example occurred in 1928, when Jung drew a mandala that looked to him very Chinese and on the exact same day received in the mail Richard Wilhelm’s manuscript of his translation of the Secret of the Golden Flower. To Jung, that was what synchronicity was all about. In the Western world, we usually assume that events develop sequentially, one after the other, by a process of cause and effect. But Jung was convinced that as well as a vertical connection, events might also have a horizontal connection—that all the events occurring all over the world at any one moment were linked in a kind of grand network. Thus when one threw the coins to consult the I Ching, the throwing of the coins coincided with one’s feelings at that precise moment and the answer reflected the truth of that moment.

The turn-of-the-century adventurer John William Dunne reported experiences that were not explicable within the usual sequential framework of time. In his book An Experiment with Time, published in 1927, he wrote of recurrent dreams in which he foresaw tragic events such as disastrous military expeditions and volcanic explosions which resulted in large-scale ruin and deaths. In 1902, at the age of twenty-seven, while a soldier in the second Boer War, he had a dream in which he saw the catastrophic volcanic explosion of Mount Pelée on Martinique. When he tried to warn the French authorities, they turned a blind eye. A few days later he read about the disaster in the newspaper. The most extraordinary thing was that the dream had occurred not at the time of the eruption, but several days later when the paper was on its way.

Dunne proposed that time might not always unfold in a straight line, as in physics. Perhaps during sleep the psyche was freed from the rigid march of time and time took on a multidimensionality in which haphazard combinations could occur. Jung wrote glowingly to Pauli about Dunne’s clairvoyance.

In May 1930, in a memorial lecture for Richard Wilhelm who had recently died, Jung spoke of the philosophy behind the I Ching, which Wilhelm had translated. He said, “The science of the I Ching is based not on the causality principle but on one which—hitherto unnamed because not familiar to us—I have tentatively called the synchronistic principle.”

Synchronicity, he often boasted, was “one of the best ideas” he ever had. His experiences as a psychologist had convinced him that scientific laws of causality were insufficient to explain “certain remarkable manifestations of the unconscious.” Jung was well aware, however, that physicists would have nothing to do with acausality. He was eager to find a way to back up his developing ideas with scientific rigor. He desperately needed guidance. It was at that point that he met Pauli.

Synchronicity and telepathy

In 1934 Pauli put his friend and successor at Hamburg, Pascual Jordan, in touch with Jung. Jordan was a highly respected physicist who had carried out ground-breaking research in the new quantum mechanics. He was also a rather eccentric character with a pronounced stutter; his wife used to attend his lectures and make bird noises to distract him whenever he lost control of his words. He modeled his hairstyle on Adolf Hitler’s, which, unfortunately, reflected his politics. (This was the friend to whom Pauli wrote the postcard addressed to PQ–QP.) In the 1930s Jordan moved from pure physics research into studying the effect of quantum physics on biology and also began looking seriously into telepathy.

Pauli sent Jung one of Jordan’s articles, which the editor of the highly respected scientific journal Die Naturwissenschaften had asked him to referee. It was on the subject of parapsychology. Pauli was skeptical but also curious. He told Jung about Jordan’s physics credentials, his speech defect, and his personal problems. Jordan often complained that he had “run out of luck in physics,” which was what had led to his “preoccupation with psychic phenomena.”

Jung was ecstatic that a physicist of such high repute was interested in the paranormal. Jordan’s interpretation of telepathy was that it was sender and receiver sensing the same object simultaneously in a common conscious space. Jung, conversely, considered that the instance of telepathy occurred not in a conscious space but in a common unconscious with only one observer “who looks at an infinite number of objects,” not just one.

Jung wrote directly to Jordan in glowing terms, congratulating him on his interest in psychology. He drew his attention to Wilhelm’s translation of The Secret of the Golden Flower. “Chinese science,” he wrote, “is based on the principle of synchronicity, or parallelism in time, which is naturally regarded by us as superstition.” Jung also suggested that Jordan look at the I Ching.

Synchronicity in physics and psychology

It was not until many years later, in 1948, that Pauli and Jung began to look deeply into synchronicity. In a letter, Pauli asked whether Jung would use the term synchronous, or synchronistic, if there was a gap of time between the dream and the external event it predicted. Jung replied, “nowadays, physicists are the only people who are paying serious attention to such ideas.” Pauli suggested Jung record his thoughts on the matter. Jung happily complied and sent Pauli a thick manuscript to read. Four years later it appeared as “Synchronicity: An acausal connecting principle,” in a book that Jung and Pauli coauthored: The Interpretation of Nature and the Psyche. The book also contained Pauli’s essay on Kepler. Before that, however, Jung had to undergo tough criticism from Pauli.

The scientific basis that Jung proposed for synchronicity lay in one of the most dramatic implications of quantum physics: that the coordination in space and time of any atomic process and its causal description are mutually exclusive. One can choose one or the other, but not both. As we saw above, the reason lay in the measurement process itself, in which the measuring apparatus and the “system being measured” (for example, the electron) were inextricably linked. This resulted in unavoidable errors and was at the root of the statistical basis of quantum physics. Moreover, the characteristics of the “system being measured” underwent an unalterable change in such a way that all its individual features were lost. Deriving his knowledge of science from Pauli, Jung interpreted this as showing that there could be other connections of events in space and time besides the causal connection. Perhaps the same applied to the psyche.

Rhine’s experiments in ESP

Jung was also intrigued by the experiments that Joseph Banks Rhine, an American psychologist at Duke University, North Carolina, performed in the 1930s and recorded in a book called Extra Sensory Perception. It was Rhine who coined the acronym ESP.

Rhine conducted a series of experiments in which a person drew a card from a shuffled deck and a test subject in another room tried to guess what it was. The subjects often achieved astounding results, guessing the correct cards 40 or 50 percent of the time. One subject was 100 percent correct.

Jung examined the archetypal basis for Rhine’s experiments. One thing that was striking was that the number of successes decreased sharply after the first attempts and eventually disappeared as the number of tests increased. Rhine attributed this to the subject’s lack of interest as time wore on. But when interest and enthusiasm were revived, along with the subject’s belief in ESP, the number of successful guesses rose.

Pauli suggested that the decline in the success rate of Rhine’s subjects was due to the “pernicious influence of the statistical method,” by which he meant that the statistical approach only dealt with large numbers of successful and unsuccessful tests. The size of the sample was so huge that the fact that some subjects had achieved an extraordinarily high success rate simply disappeared in the welter of figures and “the actual influence of the psychic state of the participants” became imperceptible.

Added to this, the mechanical nature of the experiments meant that the participants eventually got bored. As their interest in the experiment decreased, so did their psychic power, thereby blurring the initially exciting valid results. Nevertheless, this was clearly another example of complementarity, in that “any connection between causality and synchronicity can never be ascertained,” the two by definition being mutually exclusive. Acausal—that is, synchronous—events were certainly rare, in the realm of single figures. But they existed nonetheless.

Jung and Pauli were impressed by the quality of Rhine’s professed scientific standards and marveled at how his data had stood up to criticism. Pauli could see that this was important for Jung’s theory of synchronicity, based on the claim that scientific causality was not the complete story. But he could not “see any archetypal basis (or am I wrong there?),” he wrote.

Jung took up the challenge.

Jung’s astrology experiment

Around this time, Jung was conducting an astrology experiment. Having gathered data on 180 married couples, he constructed the horoscopes of each partner, hoping to find out whether the dates of birth and positions of the sun and moon for each actually correlated in the way that astrology predicted, within statistical bounds. If they did, then that could provide a scientifically verifiable proof of astrology.

Pauli was uncomfortable with this. He pointed out to his friend, the scientist Markus Fierz, who was assisting Jung with statistical calculations on his astrological data, that Jung had not included the effect of irrational factors entering from Jung’s own unconscious and that of his co-workers. “It’s a curious thought that it is we physicists who have to call the attention of the psychologists of the unconscious to this,” he wrote. In the published version of his experiment Jung admitted as much, giving instances where his state of mind and that of his co-workers affected the way in which they constructed the horoscopes. Sadly, his results did not bode well for constructing a scientific basis for astrology. Small samples, however, produced good results, which Jung interpreted as demonstrating the predominance of archetypes from astrology: even though people think they are consciously choosing their partners, in fact they are not. Just as when one consults the I Ching and in Rhine’s ESP experiments there is no cause-and-effect connection. Jung was the eternal optimist.

In 1949 Pauli wrote to Fierz:

May this now be a good omen as regards my relationship with physics and psychology, which undoubtedly is among the peculiarities of my intellectual experience. What is decisive to me is that I dream about physics as Mr. Jung (and other nonphysicists) think about physics. The danger of this situation lies in Mr. Jung publishing nonsense about physics and could moreover quote me in the process. The thing is to prevent this and to turn the matter to advantage. I simply cannot evade it! But every time I have talked to Mr. Jung (about the “synchronistic” phenomenon and such), a certain spiritual fertilization takes place.

Pauli was worried that his reputation might suffer if Jung published material on physics that made no sense and that quoted him as confirmation. But their conversations were far too fruitful to dream of abandoning them. Above all he was gripped by the notion of finding a link between quantum physics and psychology—which surely lay in synchronicity.

The scarab and the birds

Wrestling with the concept, Pauli discovered that he found it useful to make a distinction between chance occurrences of synchronicity and occurrences of synchronicity brought about by consulting oracles such as the I Ching. For chance occurrences he used the term “meaning-correspondence” rather than “synchronicity,” which Jung tended to use synonymously with “simultaneity.”

In reply, Jung brought to his attention two examples of synchronism in which he was able to identify “some archetypal symbolism at work…which cannot be explained without the hypothesis of the collective unconscious.”

The first concerned a woman patient whose animus (that is, her male aspect, the female equivalent of the male anima) clung to a stubbornly logic-based view of reality. She had already been to two analysts before Jung. He was having no success either until one day she told him about a dream of a scarab she had had. At that same moment Jung heard a tapping on the windowpane. He flung open the window and an insect flew in. Jung caught it. It was of the scarab family. To Jung this was not a chance happening but a meaningful coincidence. The patient had been disturbed by the dream scarab and the sudden appearance of a real one completely shattered her stubbornly rational attitude. The scarab bursting in through the window allowed her animus to burst its logical chains and place her on the path to psychic renewal—entirely appropriate, said Jung, given that the scarab is an ancient Egyptian symbol of rebirth. It was an example of a psychic state in the observer coinciding with an external event that corresponded to that psychic state.

The other example of synchronicity concerned the wife of one of Jung’s patients. She told Jung that when her mother and grandmother died, on each occasion a flock of birds had gathered outside the window of the room. Some time later, Jung noticed that her husband had symptoms of an impending heart problem and recommended that he see a specialist. The specialist, however, could find no problem. On his way back the man collapsed in the street. Shortly after he had set off to see the specialist a large flock of birds had alighted on the house. His wife immediately recognized this as a sign of her husband’s impending death.

Jung noted that in the Babylonian Hades the soul is adorned with feathers and in ancient Egypt the soul was considered to be a bird. It was an example of a psychic state coinciding with a corresponding, not yet existent, future event.

In Rhine’s experiments it was the subjects’ determination to achieve the impossible—to show that ESP existed—that caused them to tap into their unconscious. Dunne’s dreams showed that the psychic state can coincide with an event (like the volcanic eruption) when the subject is asleep. In both cases quieting or closing down the conscious mind enabled the subject or dreamer to open the unconscious to the external world and to allow archetypes to emerge. Divinatory procedures, such as consulting the I Ching, required this same mental condition. In each instance of synchronicity that Jung observed, an archetype appeared—the scarabs, the birds. “The effective (numinous) agents in the unconscious are the archetypes. By far the greatest number of spontaneous synchronistic phenomena that I have had occasion to observe and analyze can easily be shown to have a direct connection with an archetype,” Jung wrote.

Pauli was still doubtful about Jung’s use of the term “synchronistic” to mean “at the same time.” Surely this held only for experiences in the first category (an external event coinciding with a psychic state, as in the case of the scarab). While he was mulling over this problem, Pauli had a dream. It was October 1949.

The stranger/Merlin appears

The dream concerns a “stranger” who appeared in earlier dreams as the “blond” man.

In Jungian terms he is the voice of the collective unconscious, the background archetypes given shape—constellated—by twentieth-century scientific concepts, and represents authority. He often comments that modern physics is inadequate and incomplete and is able to move back and forth between the physical and the psychic, the conscious and the unconscious. He is an intermediary, like Hermes in alchemy, a “psychopomp,” who moves between the dark and light worlds.

While working on Kepler, Pauli read Romans de la Table Ronde (Stories of the Round Table), containing the legends of the Holy Grail. He was struck by the similarity between the “stranger” and the wizard, Merlin. Emma, Jung’s wife, was also interested in the Grail. Pauli wrote to her:

[The stranger] is a spiritual light figure with superior knowledge, and on the other hand, he is a chthonic [dark] natural spirit. But his knowledge repeatedly takes him back to nature, and his chthonic origins are also the source of his knowledge, so that ultimately both aspects turn out to be facets of the same “personality.” He is the one who prepares the way for the quaternity, which is always pursuing him…. He is not an “Antichrist,” but in a certain sense an “Anti-scientist,” “science” here meaning especially the scientific approach, particularly as it is taught in universities today…. My branch of science, physics, has become somewhat bogged down. The same thing can be said in a different way: When rational methods in science reach a dead end, a new lease on life is given to those contents that were pushed out of time consciousness in the 17th century and sank into the unconscious. [The stranger] happily uses the terminology of modern science (radioactivity, spin) and mathematics (prime numbers) but does so in an unconventional manner. Inasmuch as he ultimately wishes to be understood but has yet to find his place in our contemporary culture, he is, like Merlin, in need of redemption.

In some ways the “stranger” seems to represent Pauli himself—not surprisingly, for he springs from the collective unconscious, which, according to Pauli, has now been given “a new lease on life.”

Of the stranger, he wrote to Aniela Jaffé, Jung’s secretary:

Like Merlin, he knows the future, but cannot change it…. In my opinion, however, man can alter the “future.”…I want to recognize [Merlin], talk to him again, bring his redemption a little nearer. That, I believe, is the myth of my life.

For Pauli rational methods had reached a dead end and were no longer the tools that would enable him to change the world. Rather, the magical world of Merlin with its search for the quaternity held the key. If Pauli could only come face to face with him, he could “bring his redemption a little nearer” and so, too, with the “stranger” who could not speak a language that could be understood by everyone. Pauli believed that to move forward in examining the human psyche he needed to fuse physics with psychology. This was the “myth of [his] life,” no less heroic than that of Merlin.

In Pauli’s dream, an airplane lands and some foreigners step out, among them the stranger. He tells Pauli, “You should not exaggerate your difficulties with the notion of time. The dark girl has only to make a short journey, in order to determine the time!”

Jung’s interpretation of this dream was that the airplane represented Pauli’s intuition and the foreigners his “not-yet-assimilated thoughts.” The dark girl is Pauli’s anima. She has to “make a short journey,” that is, change her place in order to achieve definite time. At present “she has no definite time,” meaning that she lives in the unconscious. She has to transplant herself “into consciousness in order to be able to define time.” The stranger wants Pauli’s anima—the feminine side of his personality—to study the mathematics of whole numbers which are the “archetypes of order,” in order to understand synchronicity. In this way, Pauli will be able to move toward a unification of physics and psychology, the reverse of Kepler’s materialistic worldview so deplored by Fludd.

Jung concluded his letter with a new quaternary diagram:

Jung’s response to Pauli’s mandala.

In this, Jung takes space and time as complementary. Opposite the causality of physics he places “correspondentia”—the correspondence between the psychological and the physical view of life, including synchronicity.

Back to Bohr’s complementarity principle

Bohr, too, in his view of complementarity had something to say about causality:

The very nature of the quantum theory…forces us to regard the space-time coordination and the claim of causality, the union of which characterizes the classical physical theories, as complementary but exclusive features of the description, symbolizing the idealization of observation and definition respectively.

Classical physics combines how a system develops in space and time with causality (meaning a logical chain of cause and effect). The mathematical structure of Newton’s laws of motion permitted the path of an object to be traced in space and time with, in principle, perfect accuracy, that is, to predict the paths of cannonballs, falling objects, and planets. This is the law of causality. To use it the scientist needs only two pieces of information: where the object was and how fast it was moving when the process began. Knowing that a stone was six feet off the ground and dropped from a resting position, we can predict where it will be as it is falling and when it will hit the ground.

Yet Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle asserts that it is impossible to make exact measurements of an electron’s position and its momentum in the same experiment. Thus according to quantum theory it is an impossibility—an idealization, as Bohr puts it—to combine a description in space and time with causality.

According to Bohr’s complementarity principle, the description in space and time of a physical system (such as a quantum of light hitting an electron in the same way that two billiard balls strike each other) and causality (predicting where the electron and light quantum will be after they bounce off each other) are complementary and mutually exclusive. But every scientific theory must be causal or else it cannot make predictions, which are essential to science.

So can there be predictability, that is, causality, in quantum mechanics? The conservation laws of energy and momentum state that the amount of energy and momentum in a system cannot change. Scientists can apply these laws to predict the final condition of a system from its initial state.

If a quantum of light striking an electron is like two billiard balls, then it should be possible to use the laws of conservation of energy and momentum to work out where to set up instruments to detect the light quantum and the electron after they collide. In quantum physics the law of causality of classical physics—which requires precise measurements of position and momentum in the same experiment—is replaced by predictions made by the laws of conservation of energy and momentum.

A new mandala

In response to Jung’s analysis of his dream, Pauli commented that he agreed that the stranger conveyed a holistic view of nature quite different from the “conventional scientific point of view.” Unlike his colleagues, Pauli wrote, he considered the quantum mechanics as incomplete. What was required was a fusion with psychology. He had “no shortage of ‘not-yet-assimilated thoughts’,” he added wryly.

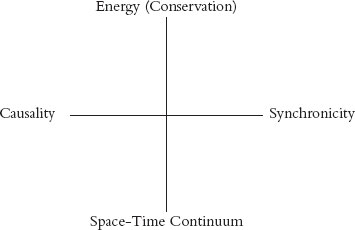

He disagreed, however, with Jung’s mandala primarily because it showed space and time as separate, whereas scientists understood that they were one—the space-time continuum. He suggested another one which included space-time while retaining the psychological element of Jung’s:

Pauli’s suggested improvement to Jung’s mandala.

Here he lays out complementary pairs, causality—the chain of cause and effect—against synchronicity; and conservation of energy against the space-time continuum, in agreement with Bohr’s complementarity principle. Classical physics pairs causality with a description in space and time. But this is an idealization. And so Pauli set in its place the law of conservation of energy; to be more precise the law of conservation of momentum should be included too.

Synchronicity in physics and psychology

The essential question Pauli felt needed to be asked was, “How do the facts that make up modern quantum physics relate to those of other phenomena explained by [Jung] with the aid of the new principle of synchronicity?” How did quantum physics sit in relation to synchronicity and other psychological phenomena. Both types of phenomena, he noted, went beyond “classical determinism.”

In Pauli’s mandala, energy and space-time, and causality and synchronicity, are complementary but mutually exclusive, like light and dark and life and death. Both arms are necessary. It is the tension between them that gives physical meaning to reality.

Pauli also noted that when Jung used “physical terms to explain psychological terms or findings,” to Jung these were “dreamlike images of the imagination.” Jung, for example, referred to radioactivity as a physical analogy for a coincidence in time—total nonsense to a physicist. Pauli proceeded to explain to Jung the notion of probability in quantum physics using radioactive decay.

In quantum physics there is a law for determining how many of a large sample of nuclei will undergo radioactive decay by emitting particles and light. But it cannot determine at what precise point in time a single nucleus will decay because it is impossible to investigate a single atom and how it develops in space and time. In other words, individual events are outside of the chain of cause and effect.

On average, half the total sample will decay in the “half-life”—a period of time that is a characteristic property of each radioactive element. After another half-life, another half of the sample will decay. But it is impossible to know when any particular nucleus will decay. To find out, one has to carry out a measurement on the system that causes decay rather than measuring when the decay naturally occurs. The law of radioactive decay is built up out of the probability of each nucleus decaying, that is, it is statistical. Moreover, the statistical regularity—the prediction of when half the sample will decay—is reproducible and has nothing to do with the psychic state of the experimenter. This is the exact reverse of experiments (such as Rhine’s) on synchronicity, which turned up a small number of examples of synchronicity that when viewed statistically were so few as to be negligible. The regularity of the half-life period could be ascertained only when there was a large number of cases, whereas in the Rhine experiments synchronicity appeared only in a small number.

Pauli’s explanation of probability in radioactive decay was also a reply to a query Jung had raised: what light does synchronicity throw on the “half-life phenomenon of radium decay?” Just as it was impossible to tell whether any one radium nucleus had decayed, similarly it was impossible to identify the precise connection of one individual with the collective unconscious. The moment when an individual nucleus decays is not determined by any laws of nature and exists independently of any experiments. Nevertheless, when someone carries out the experiment this moment becomes a part of the experimenter’s time system. The very act of measuring whether an individual nucleus has decayed alters its condition and perhaps even causes it to decay.

Pauli suggested that the state of the individual radium nucleus before the experiment was carried out might correspond to the relationship of an individual to the collective unconscious through archetypal content of which the individual was unaware. As soon as one tried to examine an individual consciousness, the synchronistic phenomenon would immediately vanish.

Pauli’s understanding of synchronicity firmly separated it from processes in physics. Jung offered quite a different definition: perhaps “synchronicity could be understood as an ordering system by means of which ‘similar’ things coincide, without there being any apparent ‘cause’…. I see no reason why synchronicity should always just be a coincidence of two psychic states or a psychic state and a nonpsychic state.” In opposition to Pauli, Jung suggested broadening the concept of synchronicity to include every sort of coincidence, whether between two psychic states or two elementary particles. He was intrigued by the fact that it is impossible to predict when an individual nucleus will decay, which opens up the possibility of phenomena in individual atoms that are beyond cause and effect.

Jung pointed out that modern physics had shown that the connection between space and time was crucial. In our daily world of consciousness, space and time remain two separate entities. “No schoolboy would ever say that a lesson lasts for 10 km,” wrote Jung. The world of classical physics had not ceased to exist—we still use Newtonian science to build bridges, for example. Similarly, despite Jung’s and Freud’s discovery of the unconscious, “the world of consciousness has not lost its validity against the unconscious.” Our commonsense perceptions about the world—of space and time as separate and consciousness as our preeminent experience—were still valid.

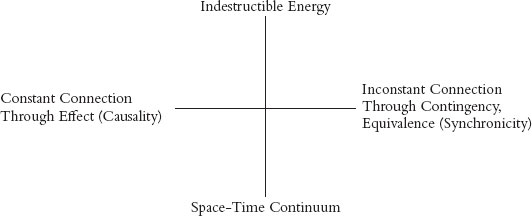

To replace the mandala he had drawn showing the world of consciousness which experiences space and time as separate, Jung proposed a more complex one that he devised with Pauli’s help.

Jung’s mandala covering all instances of synchronicity.

This, claimed Jung, satisfied the “requirements of modern physics on the one hand and the psychology of the unconscious on the other hand.”

Jung’s definition of synchronicity—that is, “inconstant connection through contingency, equivalence (synchronicity)”—Pauli replied, seemed to cover every system that was beyond cause and effect, including quantum physics. Pauli was intrigued because Jung’s broadened definition of the archetype seemed to offer a means to develop a unified view of the world. Did this mean that the concept of the archetype, too, could somehow be applied to quantum physics? Perhaps the “archetypal element in quantum physics [was] to be found in the mathematical concept of probability.”

Jung enthusiastically agreed that mathematical probability must correspond to an archetype. Bringing archetypes and synchronicity together, he suggested that the archetype “represents nothing else but the probability of psychic events.” Although all of us are born with a collective unconscious made up of archetypes, it is not inevitable that any single archetypal image will actually appear in our consciousness. It is only highly probable—not inevitable—that patients recovering from deep depression will draw mandalas.

The law of probability in quantum physics is a law of nature and laws of nature contain the patterns of behavior of the cosmos. Given that the archetype is also a pattern of behavior, does this mean that laws of nature have their bases in psychic premises? And how do archetypes enter our human minds in the first place? Jung suggested that they were “out there,” ready to be plucked out of the air, and in this way entered our minds. We are all, after all, merely small elements in one world. The origin of the word is immaterial, Jung insisted; it’s what the archetypes can do that is important.

Returning to the ever-fascinating issue of threes and fours, Jung perceived that quantum physics widened the threesome of classical physics—space, time, and causality—to include synchronicity, thereby becoming a foursome. This happy development solved the age-old problem of alchemists, encapsulated in the “so-called axiom of Maria Prophetissa: Out of the Third comes the One as the Fourth…. This cryptic observation confirms what I said above, that in principle new points of view are not as a rule discovered in territory that is already well known, but in out-of-the-way places that may even be avoided because of their bad name.”

Jung was delighted to have this unique opportunity “to discuss these questions of principle with a professional physicist who could at the same time appreciate the psychological arguments.”

Pauli’s Jungian take on Kepler and Fludd

Pauli finally published his essay on “The Influence of Archetypal Ideas on the Scientific Theories of Kepler” in 1952 in a book entitled The Interpretation of Nature and the Psyche, which also contained Jung’s essay on synchronicity. For Pauli it was a bringing together of all his work—his lectures on Kepler and Fludd, his dreams and conversations with Jung, and his correspondence with Fierz—giving shape to a subject he had been thinking about for twenty-five years.

Pauli’s focus was the process of scientific creativity and particularly its irrational side. Though scientific theories are expressed in mathematical terms, the initial discovery of the theory is essentially an irrational—not a rational—process. What role, he wondered, had prescientific thought played in the discovery of scientific concepts and what was the link between the two? He examined the rise of modern science beginning with Kepler, and applying the insights of Jung’s psychology. He argued that the process of bringing new knowledge into consciousness involved a matching up of “inner images pre-existent in the human psyche” (archetypes) with external objects. Alchemy had a critical role to play in this process. In Jung’s psychology, alchemy offered a way to resolve the tension between opposites. It emphasized the number four (the quaternity) and it also focused on the need to bring about symmetry between matter and psyche.

As Pauli put it, “intuition and the direction of attention play a considerable role in the development of concepts and ideas, generally transcending mere experience, that are necessary for the erection of a system of natural laws (that is, a scientific theory).” This leads him to ask, “What is the nature of the bridge between the sense perceptions and the concepts?” Pauli adds, “All logical thinkers have arrived at the conclusion that pure logic is fundamentally incapable of constructing such a link.” At this point Pauli introduces the “postulate of a cosmic order independent of our choice and distinct from the world of phenomena.”

He concludes that in the unconscious the place of concepts “is taken by images with strong emotional content”—that is, images of archetypes. Thus, the links between sense perceptions and concepts are archetypes—a word used in a similar sense by both Kepler and Jung. One of the forces driving a person to allow these ideas to bubble up from the collective unconscious is the “happiness that man feels in understanding” nature. Thus Kepler’s exuberance over Copernicus’s discovery of the sun-centered universe with its mandala-like quality. And thus Pauli also brings in the irrational, or nonlogical, element in scientific creativity, which he had sought for so passionately.

To put it in Jungian terms, Kepler understood the relation of the earth to the sun as being equivalent to the ego and Self. The ego is in psychological terms the center of gravity of the conscious with all its imperfections, while the Self, the totality of the conscious and unconscious, is superior to the ego and associated with archetypal images such as the mandala. No wonder, Pauli commented, that the “heliocentric theory received, in the mind of its adherents, an injection of strongly emotional content stemming from the unconscious.” Just as the mind gropes toward a state in which conscious and unconscious are balanced so, too, science gradually becomes more balanced between logic and feeling.

But full centering and the achievement of the Self can occur only when the mandala can rotate. As we saw in Chapter 5, Kepler’s mandala lacked the fourth element and therefore could not.

In psychological terms, Fludd offered a more complete view of nature based on the number four, which enabled him to see the world as more than simply a mechanical system governed by mathematics, as Kepler did. Pauli, an astute historian, was well aware of how difficult it would be to put oneself into the mind of Kepler or Fludd, living, as they did, in times radically different from our own. Jung’s work offered a way to understand them as different personality types, “a differentiation that can be traced throughout history,” wrote Pauli. Kepler was a thinking type, who focused on the parts rather than the whole, while Fludd was a feeling type who sought “a greater completeness of experience.” This meant including emotions and the “inner experience of the ‘observer’,” which Fludd did by taking into account the “power of this number”—namely four.

In the end, however, Fludd was on the wrong path. It was inevitable that modern science would develop as it did, in a way that did not bring about the fully rounded psyche. As Pauli wrote: “In my own view it is only a narrow passage of truth (no matter whether scientific or other truth) that passes between the Scylla of a blue fog of mysticism and the Charybdis of a sterile rationalism. This will always be full of pitfalls and one can fall down on both sides.”

Certainly, modern scientists could not possibly revert to the archaic and naive view of nature held by Fludd. Yet the current rationalistic view was also too narrow. The only way to broaden it would be “a flight from the merely rational.” Science is a product of Western thought. To achieve full understanding of the world about us, it requires an equal input of Eastern mysticism. It is necessary to bring together “the irrational-critical, which seeks to understand, and…the mystic-irrational, which looks for the redeeming experience of oneness.” These two forms of knowledge represent the struggle between opposites, which is at the basis of alchemy.

“Modern science,” wrote Pauli, “has brought us closer to this goal [with] the concept of complementarity,” a notion that went beyond the confines of a theory steeped in rational thought. Complementarity offered a view of irrationality and rationality as complementary aspects of the unity of thought.

Ultimately Pauli disagreed with physicists who considered quantum theory as the most complete and final description of nature. It was certainly complete, Pauli agreed, but only within a very narrow domain, with nothing to say about consciousness or life itself. It is ironic, he wrote, that although we have a highly developed and sophisticated mathematical apparatus to understand the world of physics, “we no longer have a total scientific picture of the world.” For the deep meaning of quantum physics is that—by definition—“it is impossible ever fully to understand the totality of nature.” As Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle makes plain, as soon as one grasps one truth—for example, the location of an electron—another truth instantaneously slips from one’s grasp—in this case, how fast it is traveling.

“It would be most satisfactory of all if physics and psyche could be seen as complementary aspects of the same reality,” he wrote. “To us, unlike Kepler and Fludd, the only acceptable point of view appears to be one that recognizes both sides of reality—the quantitative and qualitative, the physical and the psychical—as compatible with each other, and [one that] can embrace them simultaneously.”

AS CARL A. MEIER, the first director of the Jung Institute and editor of the Pauli/Jung letters, recalled, “neither Pauli nor Jung needed much persuading to have their works published jointly,” though there had in fact been some pressure on Pauli not to do so. As Pauli wrote to Fierz in 1954:

Many physicists and historians have of course advised me to break the connection between my Kepler essay and C. G. Jung…. I am indifferent to the astral cult of Jung’s circle, but that, i.e., this dream symbolism, makes an impact! The book itself is a fateful “synchronicity” and must remain one. I am sure that defiance would have unhappy consequences as far as I am concerned. Dixi et salvavi animam meam! [I spoke and thus saved my soul].

Looking back on Pauli’s relationship with Jung from a twenty-first-century viewpoint, it is important to remember that Jung, Pauli, and their contemporaries considered Jung’s research to be quite as important as Pauli’s work in physics. Jung’s exploration of the human psyche was just as serious as quantum mechanics’ exploration of the physical world. Whereas today we take for granted the conclusions of quantum mechanics, most of us are less ready to accept concepts like synchronicity or archetypes. They are not part of our current currency of belief. But when Pauli and Jung were having their conversations, Pauli took for granted that Jung’s research was every bit as weighty and significant as his.