15

The Mysterious Number 137

The fine structure constant

PAULI once said that if the Lord allowed him to ask anything he wanted, his first question would be “Why 1/137?”

One of his colleagues mischievously filled in the rest of the story. He imagined that one day Pauli did get the chance to ask his question. In response the Lord picked up a piece of chalk, went to a blackboard and started explaining exactly why the fine structure constant had to be 1/137. Pauli listened for a while, then shook his head. “No,” said the man who was famous for declaring of a theory, “Why, that’s not even wrong!” He then pointed out to the Lord the mistake that He had made.

The fine structure constant is one of those numbers at the very root of the universe and of all matter. If it were different, nothing would be as it is. As Max Born put it, it “has the most fundamental consequences for the structure of matter in general.” To recap: spectral lines are the lines that are the fingerprints of an atom, revealed when they are illuminated by light. The fine structure is the structure of individual spectral lines. The fine structure constant, in turn, is the immutable figure that defines the fine structure.

Pauli’s mentor, Arnold Sommerfeld, calculated the fine structure constant as 0.00729. Later scientists, however, discovered that this could be written as the simpler, more meaningful number 1/137 (that is, 1 divided by 137). It soon became known more familiarly as 137.

This number was beyond discussion. It simply had to be 1/137 because this determines the spacing between the fine structure of spectral lines, as had been discovered in the laboratory. But why this figure? Why 137? There was something about 137—both a prime and a primal number—that tickled everyone’s imagination.*

To reiterate: The three fundamental constants that make up the fine structure constant are the charge of the electron, the speed of light, and Planck’s constant, which determines the smallest possible measurement in the world. All these have dimensions. The charge of the electron is 1.61 × 10–19 Coulombs, the speed of light is 3 × 108 meters per second, and Planck’s constant is 6.63 × 10–34 Joule-seconds. All three depend on the units in which they are measured. Thus the speed of light is 3 × 108 meters per second in the metric system but 186,000 miles per second in the imperial system. All three would certainly play an essential part in a relativity or quantum theory formulated by physicists on another planet in another galaxy, but these physicists might have a different system of measurements from ours and therefore the exact figure would almost certainly not be the same.

The fine structure constant is entirely different. Even though it is made up of these three fundamental constants, it is simply a number, because the dimensions of the charge of the electron, Planck’s constant, and the speed of light cancel out. This means that in any number system it will always be the same, like pi which is always 3.141592…. So why is the fine structure constant 137? Physicists could only conclude that it cannot have this value by accident. It is “out there,” independent of the structure of our minds.

Never before in the history of modern science had a pure number with no dimensions been found to play such a pivotal role. People began referring to it as a “mystical number.” “The language of the spectra”—the spectral lines, where Sommerfeld had found it—“is a true music of the spheres within the atom,” he wrote.

Arthur Eddington and his mania for 137

In 1957, when Pauli was fifty-seven, he wrote to his sister Hertha:

I do not believe in the possible future of mysticism in the old form. However, I do believe that the natural sciences will out of themselves bring forth a counter pole in their adherents, which connects with the old mystic elements.

Perhaps the clue lay in numbers—more specifically, the number 137.

Until 1929, the fine structure constant was always written 0.00729. That year the English astrophysicist Arthur Eddington had a bright idea. He tried dividing 1 by 0.00729. The result was 137.17, to two decimal place accuracy. The actual measurement of the fine structure constant as ascertained in the laboratory, Eddington pointed out, was close to that (it was somewhere between 1/137.1 and 1/137.3). There were two ways in which scientists determined the fine structure constant. When they calculated it from the measured values of the charge of the electron, Planck’s constant, and the velocity of light, the result was 0.00729. Or they could measure the actual fine structure of spectral lines—that is, determine it in the laboratory; the most frequent value that resulted was 0.007295 ± .000005. However, the latter method required input from a particular theory and this presented a problem, for the theory of how electrons interacted with light—quantum electrodynamics—was still in flux, as indicated by the difficulties Heisenberg and Pauli experienced in their work on this very subject. With this in mind, Eddington felt justified in throwing numerical accuracy to the wind and writing the fine structure constant simply as 1/137.

Eddington had a strong mystical streak. To him, mysticism offered an escape from the closed logical system of physics. “It is reasonable to inquire whether in the mystical illusions of man there is not a reflection of an underlying reality,” he mused. Like Pauli, he struggled with the dichotomy between the two worlds, both equally invisible, of science and the spirit. He was sure that mathematics was the key that would open the door between these two worlds and he set about an obsessive quest to derive 137 however he could.

The equation for the fine structure constant is

and the charge of the electron, e, appears in this equation as e × e, or e2. As a result, besides being a measure of the fine structure of spectral lines, the fine structure constant (1/137) also measures how strongly two electrons interact.

Eddington argued that according to relativity theory, particles cannot be considered in isolation but only in relation to each other and therefore any theory of the electron has to deal with at least two electrons. Applying a special mathematics that he had invented, Eddington found that each electron could be described using sixteen E-numbers (E stood for “Eddington”). Multiplying 16 by 16 gave a total of 256 different ways in which electrons could combine with each other. He then showed that, of these 256 ways, only 136 are actually possible; 120 are not. He wrote this mathematically as 256 = 136 + 120. Like pulling a rabbit out of a hat, he thus magically produced the number 136 from purely mathematical (if dubious) reasoning.

Of course 136 was not 137, but for Eddington it was close enough. He was convinced that the elusive “one” would “not be long in turning up.” As the physicist Paul Dirac put it, “[Eddington] first proved for 136 and when experiment raised to 137, he gave proof of that!” The obsessive pursuit of 137 took over Eddington’s life. American astrophysicist Henry Norris Russell remembered meeting him at a conference in Stockholm. They were in the cloakroom, about to hang up their coats. Eddington insisted on hanging his hat on peg 137.

Eddington added to the mystery by pointing out that 137 contained three of the seven fundamental constants of nature (the other four are the masses of the electron and the proton, Newton’s gravitational constant, and the cosmological constant of the general theory of relativity). Seven, of course, is a mysterious number in itself, encompassing the seven days of creation, seven orifices in the head, and seven planets in the pre-Copernican planetary system. Eddington’s speculations were a catalyst in the search for numerical relationships among the fundamental constants of nature.

In January 1929 Bohr wrote to Pauli, “What do you think of Eddington’s latest article (136)?” Pauli hardly bothered to reply, commenting only that he might soon have something to say “on Eddington (??).” The two question marks are his. “I consider Eddington’s ‘136-work’ as complete nonsense: more exactly for romantic poets and not for physicists,” he wrote to his colleague Oskar Klein a month later. He added in a letter to Sommerfeld that May, “Regarding Eddington’s  = 1/136, I believe it makes no sense.” (

= 1/136, I believe it makes no sense.” ( is the fine structure constant.)

is the fine structure constant.)

Pauli and 137

It seemed that Pauli had not caught the 137 bug. In February 1934, however, he wrote to Heisenberg that the key problem was “fixing [1/137] and the ‘Atomistik’ of the electric charge.” At the time he was trying to find a version of quantum electrodynamics in which the mass and charge of the electron were not infinite; but no matter which way he manipulated his equations, the concept of electric charge always entered—hence the mystical “‘Atomistik’—atom plus mystic—of the electric charge.”

The problem was that quantum electrodynamics did “not take the atomic nature of the electric charge into account” when the electric charge entered the theory of quantum electrodynamics as part of the fine structure constant (that is, 1/137). “A future theory,” Pauli wrote, “must bring about a deep unification of foundations.”

As Pauli saw it, the crux of the problem was that the concept of electric charge was foreign to both prequantum and quantum physics. In both theories the charge of the electron had to be introduced into equations—it did not emerge from them. (This was similar to Heisenberg and Schrödinger’s quantum theories in which the spin of the electron had to be inserted, whereas it popped out of Dirac’s theory.)

Quantum theory exacerbated this situation in that it included the fine structure constant, 1/137 = 2 e2/hc, that is, it linked the charge of the electron (e) with two other fundamental constants of nature—the miniscule Planck’s constant, h (the smallest measurement possible in the universe and the signature of quantum theory which deals with nature at the atomic level), and the vast speed of light, c (the signature of relativity theory which deals with the universe).

e2/hc, that is, it linked the charge of the electron (e) with two other fundamental constants of nature—the miniscule Planck’s constant, h (the smallest measurement possible in the universe and the signature of quantum theory which deals with nature at the atomic level), and the vast speed of light, c (the signature of relativity theory which deals with the universe).

Pauli continued to worry about the connection between the fine structure constant and the infinities occurring in quantum theory. It was a problem that would not go away. “Everything will become beautiful when [1/137] is fixed,” he wrote to Heisenberg in April 1934. And on into June: “I have been musing over the great question, what is [1/137]?”

That year, in a lecture he gave in Zürich, he underlined the importance of eliminating the infinities that persisted in quantum electrodynamics and drew attention to the theory’s relationship to our understanding of space and time. The solution to this problem would require “an interpretation of the numerical value of the dimensionless number [137].”

So what had happened? Why did Pauli suddenly begin to discuss his thoughts on 137? Perhaps it was the effect of Jung’s analysis opening his mind to mystical speculations.

In 1935, the senior scientist Max Born, Pauli’s mentor at Göttingen who was then at Cambridge, published an article entitled, “The Mysterious Number 137.” He looked into the reasons why 137 should have such mystical power for scientists. The main reason was that it seemed to be a way in which one could achieve the Holy Grail of scientific studies—linking relativity (the study of the very large—the universe) with quantum theory (the study of the very small—the atom).

In his article he looks at some of the qualities that make the number “mystical,” prime among them being that even though it is made up of fundamental constants that possess dimensions, it is itself dimensionless. It is also enormously important in the development of the universe as we know it. He writes: “If  [the fine structure constant] were bigger than it really is, we should not be able to distinguish matter from ether [the vacuum, nothingness], and our task to disentangle the natural laws would be hopelessly difficult. The fact however that

[the fine structure constant] were bigger than it really is, we should not be able to distinguish matter from ether [the vacuum, nothingness], and our task to disentangle the natural laws would be hopelessly difficult. The fact however that  has just its value 1/137 is certainly no chance but itself a law of nature. It is clear that the explanation of this number must be the central problem of natural philosophy.”

has just its value 1/137 is certainly no chance but itself a law of nature. It is clear that the explanation of this number must be the central problem of natural philosophy.”

In 1955, at the hundredth anniversary of the ETH, Pauli addressed a huge audience in the main lecture hall of the physics department at Gloriastrasse on the subject “Problems of Today’s Physics.” Contrary to his usual style Pauli spoke from a prepared manuscript. He obviously found this difficult. With a flourish he threw the paper aside and spoke off the cuff with great passion and verve. The crux of his argument was the vital importance of the fine structure constant and also what an impenetrable problem it was. It did not merely designate how two electrons interact with each other, it was not merely a constant to be measured; what scientists had to do was “to accept it as one of the actual main problems of theoretical physics.” There was thunderous applause.

Realizing its fundamental importance in understanding spectral lines in atomic physics and in the theory of how light and electrons interact, quantum electrodynamics, Pauli and Heisenberg were determined to derive it from quantum theory rather than introducing it from the start. They believed that if they could find a version of quantum electrodynamics capable of producing the fine structure constant, it would not contain the infinities that marred their theories. But nothing worked. The deeper problems that beset physics—not only how to derive the fine structure constant but how to find an explanation for the masses of elementary particles—remain unsolved to this day.

In 1985 the brash, straight-talking, American physicist Richard Feynman, who had studied Eddington’s philosophical and scientific papers on 137, wrote in his inimitable manner:

It [1/137] has been a mystery ever since it was discovered more than fifty years ago, and all good theoretical physicists put this number up on their wall and worry about it. Immediately you would like to know where this number comes from…. Nobody knows. It’s one of the greatest damn mysteries of physics: a magic number that comes to us with no understanding by man.

The magic number 137

So where did this magic number come from? How did Sommerfeld, who discovered it, alight on it? To get a glimpse of his thought processes, we need to take a short mathematical journey.

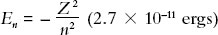

Mulling over the problem of the structure of spectral lines, Sommerfeld took another look at the key equation in Bohr’s theory of the atom as a miniscule solar system. It is

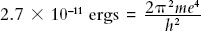

This is an equation for the energy level of the lone electron in an atom’s outermost shell, such as the electron in a hydrogen atom or in alkali atoms—hydrogen-like in structure, in that they have one electron free for chemical reactions, while all the rest are in closed shells (Pauli studied them in his work on the exclusion principle); ergs are the units in which energy is expressed. The equation shows the energy (E) of the electron in a particular orbit designated by the whole quantum number n. Z is the number of protons in the nucleus; and the minus sign indicates that the electron is bound within the atom. The quantity 2.7 × 10-11 ergs results from the way in which the charge of the electron (e), its mass (m), and Planck’s constant (h) occur in this equation:

It is also the energy of an electron in the lowest orbit (n = 1) of the hydrogen atom (Z = 1).

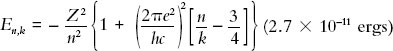

Sommerfeld decided that the mathematics in Bohr’s original theory needed to be tidied up. His brilliant idea was to include relativity in the new mathematical formulation, making the mass of the electron behave according to E = mc2, in which mass and energy are equivalent. This was the result:

In this new equation, the additional quantum number k indicated the additional possible orbits for the electron and allowed the possibility for an electron to make additional quantum jumps from orbit to orbit. It therefore also allowed the possibility of the atom having additional spectral lines—a fine structure.

The first term in the equation for En,k—outside the brackets—was the same as in Bohr’s original equation. But a whole extra term had appeared inside the large brackets.

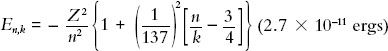

Multiplying this term was an extraordinary bundle of symbols that no one had ever seen before:  . In this expression, e is the charge of the electron, h is Planck’s constant, and c is the velocity of light. Sommerfeld deduced the number 0.00729 from this bundle of symbols. He realized that this was the number that set the scale of the splitting of spectral lines—that is, of the atom’s fine structure—and called it the fine structure constant. It is there in the equation because it is there in the atom; it is part of the atom’s existence, which includes the fine structure of a spectral line. Physicists knew the fine structure existed. They had measured the fine structure splitting, but they didn’t have an equation for it that agreed with experiment. Now they did:

. In this expression, e is the charge of the electron, h is Planck’s constant, and c is the velocity of light. Sommerfeld deduced the number 0.00729 from this bundle of symbols. He realized that this was the number that set the scale of the splitting of spectral lines—that is, of the atom’s fine structure—and called it the fine structure constant. It is there in the equation because it is there in the atom; it is part of the atom’s existence, which includes the fine structure of a spectral line. Physicists knew the fine structure existed. They had measured the fine structure splitting, but they didn’t have an equation for it that agreed with experiment. Now they did:

This extraordinary equation, in which 2 e2/hc is replaced by 1/137, perfectly described the fine structure of spectral lines as observed in experiments.

e2/hc is replaced by 1/137, perfectly described the fine structure of spectral lines as observed in experiments.

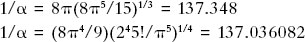

Not just scientists but many others have grappled with 137. For a start, 137 can be expressed in terms of pi. Some complicated ways of doing this, all of which end up with 137, are

We can also write 137 as a series of Lucas numbers, which are connected with Fibonacci numbers and the Golden Ratio.

Fibonacci numbers is a sequence of whole numbers in which each number starting from the third is the sum of the two previous ones. The sequence begins 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, and so on (0 + 1 = 1, 1 + 1 = 2, etc.).

If we take the ratio of successive numbers in the series—1/1 = 1.000000, 2/1 = 2.000000, 3/2 = 1.500000, 5/3 = 1.666666, and so on to 987/610 = 1.618033—we reach 1.6180339837, the Golden Ratio, which has been a guideline for architecture since the days of ancient Greece. It appears on the pyramids of ancient Egypt, the Parthenon in Athens, and the United Nations building in New York City.

Fibonacci numbers were discovered by the Italian mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci in the twelfth century. It was Kepler who discovered their relation to the Golden Ratio. Then Edouard Lucas, a French mathematician, used them to develop the Lucas numbers in the nineteenth century.

Lucas numbers are like Fibonacci numbers but begin with 2: 2, 1, 3, 4, 7, 11, 18, 29, 47, 76, 123, and so on. Like the Fibonacci series, the Lucas series also produces the Golden Ratio.

Fibonacci and Lucas numbers pop up all over the place, from how rabbits reproduce to the shape of mollusk shells, to leaf arrangements that sometimes spiral at angles derivable from the Golden Ratio.

Because all these numbers are related, any formula for 137 in terms of the Golden Ratio can be rewritten in terms of Fibonacci and Lucas numbers, though whether this is anything more than merely abstruse relationships between certain numbers is not clear.

If one tries hard enough, 137 can be deduced from devilishly complicated combinations of “magic numbers” such as 22 (the first 22 human chromosomes are numbered), 23 (the number of chromosomes from each parent), 28 (the length of a woman’s menstrual cycle), 46 (the number of pairs of chromosomes a person has), 64 (the number of possible values for the 20 amino acids in DNA), and 92 (the number of naturally occurring elements in the periodic table).

Sadly, all these are pure coincidences with no scientific basis. And still 137 continues to tantalize. In fact 137 has become something of a cult. According to one Web site, “The Fine Structure Constant holds a special place among cult numbers. Unlike its more mundane cousins, 17 and 666, the Fine Structure Constant seduces otherwise sane engineers and scientists into seeking mystical truths and developing farfetched theories.”

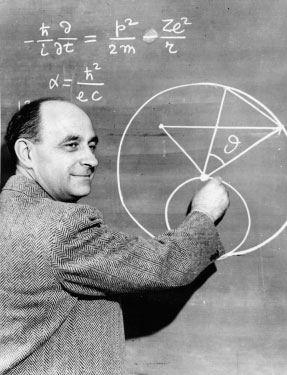

Enrico Fermi with his incorrect equation for the fine structure constant.

Even Heisenberg had a go, fired by Eddington’s number speculations. In a letter to Bohr in 1935 he reported “playing around” with the fine structure constant, which he expressed as  . He was quick to add, “but the other research on it is more serious,” referring to his and Pauli’s attempts to derive it from quantum electrodynamics.

. He was quick to add, “but the other research on it is more serious,” referring to his and Pauli’s attempts to derive it from quantum electrodynamics.

Many years later, Enrico Fermi, the physicist who christened Pauli’s newfound weakly interacting particle the neutrino, was asked to pose for a photograph. He took his place in front of a blackboard on which he had written the fine structure constant—but incorrectly. Instead of  he put

he put  . (

. ( is shorthand for Planck’s constant h divided by 2

is shorthand for Planck’s constant h divided by 2 : h/2

: h/2 .) It was an excellent joke—and a joke comprehensible only to scientists. However, the joke backfired when the photograph was used for a stamp to commemorate him after his death. So he is caught forever standing next to this iconic equation—incorrectly written.

.) It was an excellent joke—and a joke comprehensible only to scientists. However, the joke backfired when the photograph was used for a stamp to commemorate him after his death. So he is caught forever standing next to this iconic equation—incorrectly written.

Surprisingly, 137 also crops up in an entirely different context. In the 1950s, Pauli developed a close friendship with Gershom Scholem, a prominent scholar of Jewish mysticism. When his former assistant Victor Weisskopf went to Jerusalem, Pauli urged him to meet Scholem, though he gave no hint of his own interests in Jewish mysticism. Scholem asked Weisskopf what the deep unsolved problems of physics were. Weisskopf replied, “Well, there’s this number, 137.”

Scholem’s eyes lit up. “Did you know that 137 is the number associated with the Kabbalah?” he asked.

In ancient Hebrew, numbers were written with letters, and each letter of the Hebrew alphabet has a number associated with it. Adepts of the philosophical system known as the Gematria add the numbers in Hebrew words and thus find hidden meanings in them. The word Kabbalah is written  in Hebrew:

in Hebrew:  is 5,

is 5,  is 30,

is 30,  is 2, and

is 2, and  is 100. The four letters add up to…137!

is 100. The four letters add up to…137!

It is an extraordinary link between mysticism and physics. Two key words in the Kabbalah are “wisdom,” which has a numerical value of 73, and “prophesy” (64): 73 + 64 = 137. God himself is One—1—which can also be written 10 (1 + 0 = 10). Take 10’s constituent prime numbers, 3 and 7, and add the original 1: together they can be written 137.

In the bible the key phrase “The God of Truth” (Isaiah 65)  adds up to 137. So does “The Surrounding Brightness” (Ezekiel 1)

adds up to 137. So does “The Surrounding Brightness” (Ezekiel 1)  , and the Hebrew word for “crucifix”,

, and the Hebrew word for “crucifix”,  .

.

It turns out that, according to the Gematria, the number content of the letters in the Hebrew word for 137 add up to 1664. This happens to be the numerical value for a portion of the well-known passage from Revelations 13:18: “Here is wisdom. Let him that hath understanding count the number of the beast.” The rest of the passage reads: “for the number is that of man; and his number is six hundred and sixty-six.”

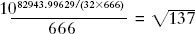

Homing in on the yet more arcane, a group of numerologists noticed that the number 82943 appeared at key places in Aztec and Roman texts and went on to argue that it was a key to a “new universal consciousness.” Their confidence in this assertion was bolstered when they discovered they could relate it to the fine structure constant and the number of the beast—666—as follows:

And more way out still, 137 is the foundation stone of a fiendishly complex “biblical mathematics” referred to by followers of “The Bible Wheel” as a “Holographic Generating Set.” It is based on three geometric forms: a cube, A, divided into 27 subcubes; a hexagon, B, divided into 37 subhexagons; and a star of David, C, divided into 73 circles Of course 27 + 37 + 73 = 137. From this “generating set” with its Pythagorean-geometric aura, aficionados of the Bible Wheel claim to be able to generate biblical passages and probe mystical numbers by multiplying A, B, and C in various ways.

Thus 137 continues to fire the imagination of everyone from scientists and mystics to occultists and people from the far-flung edges of society.

The last challenge

With World War II behind them, Heisenberg and Pauli resumed their scientific correspondence. But the days of their collaboration and the frequent exchange of letters seemed to have ended. After all, they had been on opposite sides in the war. And Heisenberg’s reputation was colored by the fact that he had remained in Germany and had ended up in charge of the German atomic bomb project. Most of his postwar colleagues, of course, had been involved in the Manhattan Project. Even Heisenberg’s brilliance was not enough to overcome this stain.

Then in 1957 Heisenberg wrote to Pauli that he had the germ of a theory that could explain the masses of elementary particles as well as most of the symmetries. In a preliminary test he was almost able to deduce the fine structure constant from his new theory. In his calculations it came to 1/250, which is not very far away from 1/137, in the same way as 1/3 is not far from 1/4, even though 3 is far from 4. This was extraordinary, given that Heisenberg’s theory was still in its formative stages. Pauli immediately took up Heisenberg’s suggestion to join him in his project.

“Never before or afterward have I seen [Pauli] so excited about physics,” Heisenberg later recalled. It seemed as if the old days had come back. The two giants of quantum physics were working together once again.

“The picture keeps shifting all the time. Everything in flux. Nothing for publication yet but it’s all bound to turn out magnificently,” Pauli wrote exuberantly to Heisenberg at the start of 1958. “This is powerful stuff…. The cat is out of the bag and has shown its claws: division of symmetry reduction. I have gone out to meet it with my antisymmetry—I gave it fair play—whereupon it made its quietus…. A very happy New Year. Let us march forward toward it. It’s a long way to Tipperary, it’s a long way to go.”

Heisenberg was equally excited. For him the theory was to be the culmination of his life’s work. Over the years he had become entranced by the power of mathematics to probe and understand the physical world. And he knew how to use it. “A wonderful combination of profound intuition and formal virtuosity inspired Heisenberg to conceptions of striking brilliance,” a colleague wrote. He had used his formidable insight and daring to apply mathematics to make his startling discoveries in quantum mechanics. These included the uncertainty principle; the first steps toward understanding the force that holds the nucleus together; and his attempts to produce a coherent theory of electrons and light, known as quantum electrodynamics.

The theory he was working on with Pauli was exactly what he was looking for. “The last few weeks have been full of excitement for me,” he wrote to his wife’s sister Edith in January 1958:

I have attempted an as yet-unknown-ascent to the fundamental peak of atomic theory with great efforts during the last five years. And now, with the peak directly ahead of me, the whole terrain of interrelationships in atomic theory is suddenly and clearly spread out before my eyes. That these interrelationships display, in all their mathematical abstraction, an incredible degree of simplicity, is a gift we can only accept humbly. Not even Plato could have believed them to be so beautiful. For these interrelationships cannot have been invented; they have been there since the creation of the world.

Perhaps he also saw it as his chance to vindicate himself, to put behind him the fact that he had been the leader of the German atomic bomb project.

Together Pauli and Heisenberg wrote a joint paper that Pauli planned to lecture on during his forthcoming visit to the United States that January. Before leaving he wrote to Aniela Jaffé. He had been entirely engrossed in work with Heisenberg on a “new physical-mathematical theory of the smallest particles,” he said.

The pace of their work was so overwhelming that often letters were not fast enough. The phone line between Zürich and Munich, where Heisenberg was based, was continually buzzing. For Pauli their research was so fundamental that he saw Jungian significance in it. Although he and Heisenberg were very different, he wrote to Jaffé, they were “gripped by the same archetype”—by reflection symmetry, in the fullest sense of the CPT reflection. “Director Spiegler! [Reflector] dictates to me what I should write and calculate,” he declared.

He hoped that the “new year will see a beautiful theory that will light up the world.” He had even had a dream about it: Pauli enters a room and finds a boy and a girl there. He calls out, “Franca, here are two children!” He had seen Heisenberg just three days earlier and interpreted the children as the new ideas which he was confident would emerge from their work. From the fact that there were two children, he drew an analogy to his “mirror complex.”

The work could be taken as a realization of the unconscious and “more specifically: a realization of the ‘Self’ (in the Jungian sense).” It was what Pauli had sought for years—physics and the psychology of the unconscious as mirror images, a scenario that had been destroyed by the violation of mirror symmetry (parity violation), but restored by CPT symmetry, Pauli’s 1955 discovery about which he was still exultant.

On February 1, 1958, the lecture theater at the physics department at Columbia University was packed with over three hundred people. They were eager to see the great Pauli who was about to lecture on a theory formulated by the two giants of quantum theory. Niels Bohr, J. Robert Oppenheimer, T. D. Lee, and C. N. Yang, who had proposed the overthrow of parity, and C. S. Wu, the physicist who had performed the crucial experiment to prove it, all attended. The air was electric. But the distinguished audience had nothing but criticism for the new theory, though offered in a friendly manner. A key point in the theory was how newly discovered elementary particles decayed, how they transformed themselves into other particles. As Pauli was scribbling the equations on the blackboard, Abraham Pais, an eminent physicist and friend of Pauli’s, raised his hand and objected, “But Professor Pauli, this particle does not decay like that.” Pauli stopped midflow. There was a long silence. Then Pauli muttered, “I must get in touch with my friends in Göttingen about that,” by which he meant Heisenberg. At this point, T. D. Lee remembers, you “could almost feel the silence.” Others too pointed out loopholes in his mathematical proofs. Pauli continued his lecture but it was clear that the passion had gone.

At one point Bohr and Pauli chased each other around a long table at the front of the room. Whenever Bohr ended up at the front he declared, “It is not crazy enough.” Each time Pauli appeared he replied, “It is crazy enough.” This was repeated several times and the audience burst into applause.

“We were all polite, but Pauli was obviously discouraged…It was obvious that his heart was no longer in their work,” Yang recalled. He vividly remembered Pauli’s gloom as they were on their way in Lee’s car to a restaurant after the lecture. “Pauli oscillated back and forth in his seat and murmured some thing which I thought was, ‘As I talked more and more, I believed in it less and less.’ I was greatly saddened.” The physicist Freeman J. Dyson, of the Institute of Advanced Study, commented that it was “like watching the death of a noble animal.”

So what had happened? How could Pauli have been so enthusiastic about this new approach and then so totally cast down? Presenting a lecture on a subject can shed an entirely new light on it. So perhaps that was what happened. Suddenly he realized that the theory was full of holes. He was beginning to have second thoughts about his work with Heisenberg.

The following day he lectured at the American Physical Society meeting in New York, at that time the biggest and most important annual gathering of physicists from around the world. There was standing room only. But the criticism meted out by a younger and brasher generation of American physicists was even harsher. Lee could not bring himself to attend.

From there Pauli went on to California—where Feynman, for one, had had no compunction about telling the great Bohr that he was an idiot. Audiences there too offered ruthless criticism. Pauli was beginning to conclude, as he wrote to Heisenberg later that year, that “something entirely new, in other words very ‘crazy,’ [was] needed” if he and Heisenberg were to crack the mystery of the masses of elementary particles, one of the key aims of their unified theory.

Disillusioned, Pauli attacked Heisenberg’s calculation of the fine structure constant as 1/250, which had seemed so promising and had played a part in his decision to join Heisenberg’s project. He wrote to Fierz bitterly, “I have never considered it as correct. It’s so totally stupid.”

Some time later, Heisenberg’s co-worker on that calculation, Renato Ascoli, recalled that he had originally deduced the fine structure constant as 8 on the basis of Heisenberg’s theory. “Only after Heisenberg had doctored it up, was the value reduced to 1/250.”

Later that month Heisenberg gave a lecture on his and Pauli’s work at Heisenberg’s Institute in Göttingen. The room was packed. The great Heisenberg was about to announce a theory that could explain the behavior of every elementary particle in the world with a single equation—a “world formula”—that would surely prove to be an abstruse and highly technical piece of mathematics.

A press release was circulated reading (most offensively to Pauli): “Professor Heisenberg and his assistant, W. Pauli, have discovered the basic equation of the cosmos.” The story was picked up by newspapers around the world. Pauli vented his anger in a letter to George Gamow, the physicist and prankster who had translated and illustrated the Mephistopheles spoof at Bohr’s Institute in 1932. Pauli lampooned it by drawing an empty box saying, “This is to show that I can paint like Titian: Only the technical details are missing”—a case of the emperor’s new clothes. Pauli requested Gamow not to publish his comment but, miffed at Heisenberg’s insulting press release, added, “please show it to other physicists and make it popular among them.” Gamow certainly did. A week later Weisskopf wrote to Pauli about the press release and added that he read it with Pauli’s comment about Titian well in mind.

Combining Pauli’s well-known obsession with 137 with Heisenberg’s for his new theory, a colleague wrote jokingly to Pauli, “Since the Heisenberg equation is supposed to describe everything (see, for instance, New-York Herald Tribune, volume 137, p. i/137), it has as one of its solutions Heisenberg himself.” Pauli replied, “Regarding Heisenberg I have the feeling, that the situation is slowly growing over his head; certainly he needs vacations.” The problem of how to describe the properties of elementary particles remained open. Pauli summed up the situation thus, “Many questions, no good answers.”

In fact, Pauli was furious. He wrote to C. S. Wu about Heisenberg’s “poor taste” as far as the press releases were concerned:

In some of these I had been, unfortunately, mentioned…but fortunately only in a “mild” form as a secondary (or tertiary) auxiliary person of the Super-Faust, Super-Einstein and Super-man Heisenberg. (He seems to have mentioned his dreams on gravitational fields—about which one has not worked at all in Göttingen recently—and his revival of the old idea of a “world formula”—which was never successful—in a quantized form.)

He seems to have been relieved that he was not associated too closely with Heisenberg’s mistaken schemes. To Wu he recalled his hopes, dreams, and aspirations of thirty years earlier when he and Heisenberg were young and Heisenberg depended on his friend’s criticism and inspiration. Now Pauli had had enough:

Heisenberg’s desire for publicity and “glory” seems to be insatiable, while I am in this respect completely saturated. I only need something in science which interests me sufficiently and with which I can play (without being a hero in the limelight of the “world.”) Heisenberg’s opposite attitude, with which he certainly wishes to compensate earlier failures, may have many reasons lying in the whole history of his life.

No doubt the last words were an oblique reference to the role Heisenberg played in the war.

Soon afterward Pauli withdrew from the collaboration. Heisenberg persisted in making promise after promise as to the wonders his theory would produce. “He believes that if he publishes with me, then it is 1930 again! I have found it embarrassing how he runs after me!” Pauli wrote to Fierz in May.

That July Pauli chaired a session at a conference at CERN at which Heisenberg was scheduled to speak. Pauli introduced Heisenberg with the words, “What you will hear today is only a substitute for fundamental ideas.” He went on to make a request of the audience: “don’t laugh in the wrong place, ha, ha, ha….” The audience was already in fits of laughter. Pauli let Heisenberg finish speaking, then mercilessly demolished his paper.

When Pauli and Heisenberg met again later that summer, Heisenberg noticed that Pauli looked dispirited. Pauli encouraged him to go on with his work and wished him well, but added, “For me, I have to drop out, I just haven’t the strength, and that’s that. Things have changed too much.”

Could it have been that the great criticizer had met his match in the lambasting he encountered in America? To be on the receiving end must have been shattering. Heisenberg had been afraid this would happen when Pauli “in his present mood of exultation [encountered] the sober American pragmatists.” Franca too had noticed this chink in Pauli’s armor which, up until then, he had concealed so successfully: “He was very easily hurt and therefore would let down a curtain. He tried to live without admitting reality. And his unworldliness stemmed precisely from his belief that that was possible.”

But there was something else that brought Pauli to the point of spiritual exhaustion. He had grown attached to his work with Heisenberg. Their new theory had all the trappings that he thought a theory should have: a high degree of mathematical symmetry and Jungian meaning too, taking it one step closer to not merely a unified theory of elementary particles from which the fine structure constant could one day be deduced, but to a theory of the mind as well.

As he always did, Pauli interpreted the failure of the theory as personal failure. Genius though he was, he had failed yet again. Those who saw him in the autumn of 1958 recalled that he seemed beaten.

That year Pauli told an interviewer, “When I was young I thought I was the best formalist of my time. I believed that I was a revolutionary. When the great problems would come, I would be the one to solve them and to write about them. Others solved them and wrote about them. I was but a classicist and no revolutionary.” He began writing letters as if saying farewell.

A different side of Pauli

It was not all gloom. During his visit to the United States that year, Pauli had visited Harvard. Among the delegation that greeted him was Roy Glauber.

Glauber had been a postdoctoral fellow at the ETH back in 1950, working under Pauli. “Pauli…had been a legendary figure since his early twenties. Some part of that legend, as Pauli well knew, was attached to his role as a critic, not always kindly, of the work of his colleagues. So no one who knew Pauli, it is fair to say, could be in his presence without feeling a certain defensive wariness,” he remembered many years later.

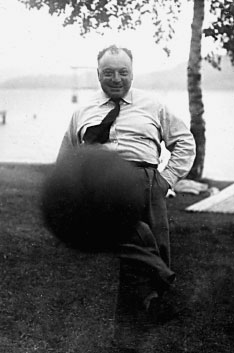

Not long after young Glauber arrived in Zürich, he and the rest of Pauli’s students went on a hike in the hills. They took a cable car and then followed a series of steep trails around the Vierwaldstätter See, a scenic lake. “Pauli, notwithstanding his ample girth,” kept up a vigorous pace. Expecting a picnic, Glauber had brought a camera, a hefty Speed Graphic—made famous in the 1940s and 1950s by press photographers—which hung by a strap over his shoulder. He had not even brought much film. Pauli began teasing him. “Always you carry that awful camera,” he kept saying, “but you are taking no pictures.” Then he laughed uproariously.

At the end of the day, some of the group swam in the lake while others played soccer. Pauli kicked the ball into the lake so that someone had to swim out and fetch it. He roared with laughter as he kicked the ball further and further into the water.

A photograph of Pauli kicking the ball was too good to miss—but Glauber had only one exposure left. Trying not to draw Pauli’s attention, he set up his camera, peered into the rangefinder and as inconspicuously as possible signaled a friend to kick the ball toward Pauli. Suddenly the camera smacked him square in the face. Instead of the lake, Pauli had decided to make Glauber’s camera his next target. Glauber recalled hearing his bellowing laugh.

Pauli kicking a soccer ball, 1950.

He had, however, managed to snap the shutter. “Pauli,” he concluded, “never discounted the element of luck in his practical jokes.”

When Glauber was still at the ETH, his mother once wrote and complained to Pauli that her son never sent letters home. Thereafter, whenever Pauli saw Glauber, he always insisted on asking loudly, “And how is your dear mother?”

In 1958, when Pauli visited Harvard, Glauber was apprehensive. To his relief Pauli greeted him warmly and said nothing the entire time about his mother. “Thank God he has forgotten my mother,” Glauber said after he had left. Pauli went with Weisskopf back to his lodging in Cambridge. The first thing he said once they were out of earshot was, “This time I fooled Glauber. I said nothing about his mother.”

A nearly perfect sphere

That same year Pauli attended the Solvay Conference in Brussels as that venerable meeting’s vice president. There he and Franca invited the cosmologist Fred Hoyle and his wife to lunch. Honored, Hoyle happily accepted. He was eager to substantiate a story about Pauli that had been on his mind for some years, of how, in the 1920s, after a lecture by Einstein on relativity, Pauli had had the temerity to say to the audience that what Professor Einstein said “was not so stupid.”

But Pauli had his own agenda. “Aha,” he cackled, “I just read your novel The Black Cloud. I thought it much better than your astronomical work.” Hoyle had recently proposed a theory asserting that the universe around us has always existed exactly as we see it. He called it the “steady-state theory” to distinguish it from what he dubbed the “big bang theory”—that is, that the universe came into being at a specific moment in time and evolved into what we see today. Pauli was far from impressed with Hoyle’s theory.

He told Hoyle that both he and Jung had read Hoyle’s novel carefully and that he was writing a critical essay on it. Hoyle was mystified. After all, it was only a story—about how an intelligent life-form learns to communicate with earthlings. He had never felt it merited such deep analysis.

Finally Hoyle had the chance to ask Pauli about the Einstein story. “My abiding memories of Pauli,” he wrote, “are of his helpless laughter as the youthful remark about Einstein came back to him and his rolling back and forth, a nearly perfect sphere.” But Pauli said no more, “so I never quite had it from Pauli personally that the story was true, but those who knew him well assure me it was.” Another lasting memory that Hoyle carried away from the lunch was the four bottles of fine wine on the table.

The Pauli effect strikes again

That same year the physicist Engelbert Schucking visited Pauli in Zürich. Along with Pauli’s assistant Charles Enz and another colleague they took a tram from the ETH to Bellevue Square, where they planned to have a “wet after-session,” with plenty of drinking. Bellevue Square is a bustling intersection where several tram tracks cross each other in a seemingly random way. Just as they reached the square, two street cars collided right in front of them with an enormous bang. Schucking was standing with Pauli next to the driver of the street car. “Pauli’s face was flushed as he excitedly turned to me and exclaimed, ‘Pauli effect!’” Schucking recalled.

Enz told Schucking about a lecture Pauli had given to an audience of high-level government officials on an occasion honoring Einstein, the ETH’s most famous graduate. “Pauli read from his manuscript. Whenever he found an error in his text, he stopped in mid-sentence, drew out his fountain pen, corrected the text and went on, oblivious of the squirming audience.” It was a teaching style he had maintained throughout his career.

That November Pauli was in Hamburg. Schucking took a walk with him. As they walked along the Gojenbergsweg in the Bergdorf district, looking out over the marshland of the river Elbe, Pauli said several times how glad he was to have withdrawn his name from the paper with Heisenberg.

On Friday, December 5, 1958, as he was teaching his afternoon class, Pauli suddenly began to suffer excruciating stomach pains. Up until then he had been fine. The next day he was rushed to the Red Cross Hospital in Zürich. Charles Enz visited him the day after. Pauli was visibly agitated. Had Enz noticed the number of the room, he asked him?

“No,” replied Enz.

“It’s 137!” Pauli groaned. “I’m never getting out of here alive.”

When the doctors operated, they found a massive pancreatic carcinoma. Pauli died in Room 137 on December 15. His last request had been to speak to Carl Jung.

PAULI was cremated on December 20 and later that afternoon an official funeral ceremony was held at the Fraumünster Church in Zürich, which dates back to the Carolingian period. The ceremony was non-religious. Niels Bohr, Markus Fierz, the party-giver Adolf Guggenbühl, Pauli’s treacherous colleague Paul Scherrer, and his one-time assistant Victor Weisskopf all gave addresses. Franca arranged the funeral. Only physicists spoke. Among the many who attended were Pauli’s confidant Paul Rosbaud. Jung, now eighty-two, was relegated to a place at the back. Despite his long association and close friendship with Pauli, he was not invited to speak.

One notable absentee was Heisenberg. The ETH had sent Heisenberg’s invitation on the sixteenth, giving him plenty of time to travel from his home in Munich to Zürich to pay his last respects to the man who had been his lifelong friend and colleague and had sparked his greatest discoveries. Heisenberg did not even bother to write a letter of condolence to Franca but left it to his wife. He was, she wrote, reading Pauli’s philosophical writings, but due to the Christmas season they were too busy to attend.

It is extraordinary that Heisenberg would spurn his old friend in this way. Despite their recent falling out, one would have assumed that he would have put all that behind him and attended. The only possible explanation is to be found in Heisenberg’s autobiography, written over a decade after Pauli demolished the theory he was so proud of. “Wolfgang’s attitude to me was almost hostile,” he wrote of that episode. “He criticized many details of my analysis, some, I thought quite unreasonably.” Presumably Heisenberg never forgot what had happened. The intensity with which these men treated their passion—physics—went far beyond the grave.

Hertha also did not attend her brother’s funeral. Perhaps travel was difficult financially for her; perhaps she wanted to remember Wolfgang the way he was; or perhaps she felt uneasy around Franca. Hertha had married E. B. Ashton, an immigrant from Munich, born Ernst Bach. He was a professional translator and they collaborated on several of her books. As she recalled, “we decided he would remain my ‘better English’” and married in 1948. As Franca put it contemptuously, she “married her translator.” The couple lived happily in a large farmhouse in Huntington, Long Island. Like her brother, Hertha had no children. She published several biographies and historical studies in addition to her books for children on Catholic themes. In the course of her prolific career she became an eminent member of PEN—the worldwide association of writers—and was awarded the Silver Medal of Honor by the Austrian government in 1967. Hertha died in 1973, predeceasing her husband by ten years. Their ashes were interred in the Schütz family grave in Vienna, near where she and Wolfi had grown up.

Pauli’s ashes were interred in the graveyard in the town where he had lived, Zollikon, between Zürich, where the ETH is, and Küsnacht, where he used to visit Jung in his Gothic mansion—the two places that defined his two worlds of physics and psychology.

Franca was curious about the story Enz told about room 137. Pauli had never said a word to her about this mysterious number. Enz assured her that he was repeating “Pauli’s own words.” He told her about the significance of the number in physics and that Pauli had mentioned it many times.

Franca wrote a letter to Abdus Salam, a physicist whom Pauli had greatly respected, asking whether it was he who had written “an article connected with the subject Pauli and the number 137.” She added, “it is a strange fact that Wolfgang Pauli actually died in the room Nr. 137.” People thought that Pauli had requested that room, she said. In fact he had originally been in another room and was transferred to room 137 without being told where he was being sent.

It was Salam, in fact, who originated the story of Pauli going to heaven and asking the Lord to explain “Why 137?” That had been in 1957, the year before Pauli’s death. Salam wrote to Franca, “of course it is a story which I would not repeat now.” He sent her a copy of his lecture in which the story appeared.

Franca replied, “At last I got a written, beautiful explanation of this to me so elusive Number 137. I enjoyed the end of the story—I did not know—‘convincing the Lord a mistake had been made.’ One could not characterize Pauli better in so few words!”

FRANCA died in 1987. She spent the three decades after her husband’s death finding suitable places for his books, personal papers, and correspondence. She also did her best to delay the publication of his correspondence with Jung. To the end Franca believed that it would detract from his image as a serious scientist.