YOU’RE WATCHING MOVIES TRYING TO FIND THE FEELERS

The British pop music film, at its peak through the late fifties and sixties, can be seen to fulfil Richard Dyer’s definition of a sub-genre enjoying a three-part life-cycle: the ‘primitive’ and innocent Tommy Steele and Cliff Richard musicals giving way to the ‘mature’ Pop Art knowingness of A Hard Day’s Night and Catch Us If You Can (John Boorman, 1965), which then lead on to the ‘decadent’ phase, a shrinking maze of self-referentiality and psycho-political pretension, with Jean-Luc Godard’s Sympathy for the Devil (1968) and Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance (1970) (Dyer 1981: 1484; Glynn 2013). Tommy can be seen as fitting in with this latter phase: while it had clearly been successful in bringing a new, non-rock oriented audience to the work, the film was, for rock aficionados, a betrayal. Andrew Sarris spoke for the latter when he noted that ‘we fans like what we see in Tommy because it confirms our belief that Rock has entered its mindlessly decadent phase, all noise and glitter and self-congratulation’ (Village Voice, 31 March, 1975). From the early seventies, though, pop music and its film treatment were of sufficient age to reflect on their own history, providing a lengthy if intermittent coda to the genre, its fourth historical or revisionist phase, latterly labelled ‘alternative heritage’ (Luckett 2000: 88) or ‘youth heritage’ (Leggott 2008: 98). Contemporaries of the Who’s ‘Quadrophenia’ album had been the David Essex films That’ll Be the Day and Stardust. Now America was following suit with Grease (Randal Kleiser, 1978) and The Buddy Holly Story (Steve Rash, 1978).

By the time the original concept had made it to the cinema screen Tommy was close to six years old – a dinosaur in pop culture chronology: critic Jon Landau headlined his review ‘Too Big, Too Late’ (Rolling Stone, 24 April 1975). Why then again, six years later, was this the right time for ‘Quadrophenia’ to gain a film treatment? Firstly, it was indicative of the Who’s growing bankability in the film business. Secondly, the Who had attained financial independence: with the money gained from Tommy, the group could now make the films they wanted when they wanted. Thirdly, they desperately wanted to make another film after Tommy in order to redress its many wrongs. Though nominally a British film, Tommy had been made with an American cast, American money and the focus on an American market. The band, like many of their fans, had not been over-enamoured of the final product, and used the royalties to move back to realism from tinsel, ensuring that ‘their next cinematic foray should remain as British as possible, with no concessions to the overseas market’ (Catterall and Wells 2001: 147).

To that end, and fourthly, it is hard to name a more British foray than Mod and now, post-punk, it was again, thanks largely to Paul Weller and the Jam, part of the Zeitgeist. A short film, Steppin’ Out (Lyndall Hobbs, 1979), investigated London nightlife and included Mod revivalists Secret Affair and the Merton Parkas, plus a visit to a roller disco. Seemingly incompatible, that linking of Mod and disco had also been relevant to John Badham’s international success Saturday Night Fever (1977). As Blow Up had been the first Who film by proxy, so too was this the first major Mod film manqué, John Travolta and his Bay Ridge cohorts living for the weekend high being a cultural transposition of Ace Faces and their Tickets. Nik Cohn’s source story ‘Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night’ had been immediately optioned by Tommy producer Robert Stigwood for his next epic production – and given an upbeat, happier Hollywood ending. While set in Brooklyn, expat Cohn admitted to compensating for his lack of knowledge about American neighbourhoods by borrowing characters and attitudes from what he knew best – the mid-sixties Mod scene in Shepherd’s Bush: ‘Tony and the Faces are actually Mods in everything – except the dances’ (Melody Maker, 1 April 1978). Cohn even borrowed the gang name, not directly from the Who but from the group of fans Meaden organised to swell their early gigs, the Hundred Faces.

Thus the Who’s own Mod revival was ripe for reworking, re-modifying. Because the group had so quickly abandoned stage performances, there was, unlike with Tommy, little public preconception on how the story should map out. This freedom to experiment was first offered to Cohn and Chris Stamp but they failed to deliver a workable script, being too focused on the Meher Baba-influenced spiritual journey of Jimmy Cooper. Bill Curbishley stepped in and brought along as co-producer Roy Baird whom he knew from his longstanding work for Ken Russell. Baird held various production roles on all Russell’s films from Women In Love (1969) through to Lisztomania – with the singular exception of the Stigwood-driven Tommy. Prior to that he had been assistant director on numerous projects ranging from comic double act Morecambe and Wise in The Intelligence Men (Robert Asher, 1965), Terence Stamp in The Collector (William Wyler, 1965) and David Niven in the Bond spoof Casino Royale (Ken Hughes et al, 1967). As well as making amends for Baird’s omission from Tommy, the new project also gave Baird a chance to even the tribal score: fifteen years earlier he had been assistant director on the one British film devoted to the ‘ton-up’ boys, precursors to the unmentionable Rockers, Sidney J. Furie’s The Leather Boys (1963).

I AM NOT THE ACTOR

On 9 November 1977 the attention of the British television-watching public was drawn to a ninety-minute ATV docudrama, written by Hugh Whitemore and starring Geraldine James. Dummy told the true story of Sandra X, a young deaf girl who, after undergoing years of special treatment, was rejected by an uncaring society and forced into back-street prostitution before being imprisoned for murder. The programme provoked questions in Parliament, but provided an answer for Pete Townshend and the producers of Quadrophenia. Here was a programme that featured a Tommy-like innocent, but had been filmed with the stark and harrowing realism they were seeking. The director-producer was 30-year-old Franc Roddam, from Stockton-on-Tees, County Durham. He had begun his career at the London Film School where one of his short films Birthday was nominated as the Best Short Film of 1970 in the Society of Film and Television Arts’ awards: subsequently shown at the Berlin festival, it was bought and distributed by Universal in the United States. Roddam then spent some time as a writer / producer with an advertising agency – an ethos he parodies in the cigarette campaign in Quadrophenia – before joining the BBC where he directed The Fight, a behind-the-scenes look at the 1973 Joe Frazier-Joe Bugner heavyweight boxing contest. His next project, equally belligerent, brought him public as well as Industrial renown: alongside Paul Watson he directed The Family (1974), one of the first explorations of ‘reality TV’. Modelled on the American television series An American Family (Robert Aller, 1972), Roddam’s twelve-part ‘fly-on-the-wall’ documentary series followed the everyday dealings of the Wilkins family of Reading and won both healthy viewing figures and the 1974 Critics Award. Roddam won the award again in 1975 for Mini, a film about a 12-year-old arsonist, while in 1976 he was commissioned by Dustin Hoffman to direct the short film Dancer, a study of Hoffman’s ballet dancer wife, Anne. For Quadrophenia, Roddam felt he ‘went through a sort of audition period’, first approached by Baird and Curbishley before finally meeting Townshend and bonding through a discussion of punk and its values (NME, 12 May 1979). As with Jeff Stein, no-one baulked at Roddam’s lack of experience in feature films – nor his early leanings towards the beatnik movement – and on 16 June 1978 he was contracted as the director and driving force for Quadrophenia and granted a budget of $3 million (just over £1 million) from Polytel, the German company which owned the Polydor record label on which the Who recorded.

Thereafter Townshend and the Who stepped aside, and Roddam got to work on the script. His strategy, endorsed by Townshend, was to take ‘the essence of the idea, the guts and power of the music and turn that into celluloid’ (ibid.). No-one was interested in a pale copy of Tommy where the music had dominated the film and controlled the narrative. Here the music from ‘Quadrophenia’ would contribute to and support the narrative, but not take over. Though the basic story-line of the album survived, substantial subtractions and additions would be made to Townshend’s original design. Roddam stated at the outset that he wanted the film to work ‘on several levels. As nostalgia, as a rock film with all the music … in its own right as a story, and as something with a social and contemporary relevance’ (NME 14 October, 1978). To help him in this task Roddam contracted Dave Humphries, a fellow television regular who had contributed to television cop series Target (1977–78), The Professionals (1977–83) and Hazell (1978), though his only film work (if one forgives and forgets a writing credit alongside Jackie Collins for The Stud [Quentin Masters, 1978]) had been the screenplay to Full Circle aka The Haunting of Julia (1976), a supernatural tale starring Mia Farrow. This had a promising provenance, though, having been directed by Richard Loncraine, who previously had directed the British rock group Slade in another role-model pop music film, the naturalistic Flame (1974).

Just as Townshend and Nevison had ordered the hours of tapes for the original album, Roddam and Humphries had to pull into shape myriad avenues of adaptation. Cinematically there was little agony of influence: Primitive London (Arnold L. Miller, 1965), a low budget exploitation documentary set in Soho, had brief interviews with Mods, Rockers and beatniks at the Ace Café, while at the other end of the cultural spectrum Mods and Rockers (Kenneth Hume, 1965) expressed, over 28 minutes, differences in the eponymous subcultures though the medium of ballet. That was all. To gain the appropriate attitude and atmosphere the writers turned instead to contemporary texts such as Charles Hamblett and Jane Deverson’s Generation X (1964). For facts and fashion they researched newspaper files and photographs of the period – Dr Simpson’s Margate invective to ‘discourage you and others of your kidney who are infected with this vicious virus’ is taken almost verbatim from the press as is James Brunton’s terse rejoinder to ‘pay by cheque’, while a scene of Rockers pushed down the sea wall is a precise visual recreation of a front-page snapshot. Pieces of the writers’ own histories were worked in – Jimmy’s uncle falling down a well is an event from the Roddam family archives. Perhaps most productively, they interviewed original participants such as ‘Irish’ Jack Lyons for memories of the Goldhawk Road Social Club and Alan Fletcher for south coast shenanigans – the scene where Mods Chalky and Dave bed down in the Arches with a cellar full of Rockers is his. Even early manager Pete Meaden had been feeding in ideas before his death from a barbiturate overdose in August 1978. Three weeks later, 7 September, Keith Moon died, again from a drug overdose, after attending a midnight viewing of The Buddy Holly Story. After brief concerns that the Who and therefore the film might fold, Baird confirmed that work could continue and when the material was sufficiently shaped, freelance journalist, playwright and former Mod Martin Stellman was called in to authenticate the dialogue.

I AIN’T DONE VERY MUCH

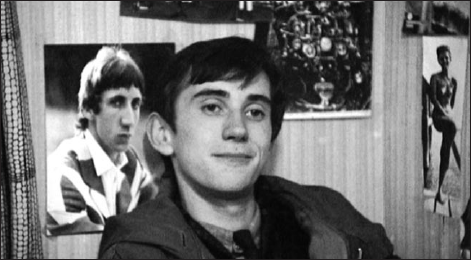

This would all be roughened further by Roddam’s encouragement of improvisation from his young cast, whose selection was a widely publicised affair. The Sun newspaper ran an advertisement in July 1978 calling for prospective Jimmy Coopers to make themselves known, and early applicants included the lead singer of the Sex Pistols, Johnny Rotten (John Lydon). He even underwent a screen-test but – with all publicity sometimes not being good publicity – the film’s insurers vetoed the casting as they considered the singer too unreliable. Jimmy Pursey of Sham 69 was also considered for the role: waiting in the wings, however, was a young but already experienced actor, Phil Daniels. At the time best known for a recent David Bailey advert for Olympus cameras (‘That’s David Bailey!’ ‘Oo’s ’e, then?’), Daniels had begun his television career with a walk-on part in The Naked Civil Servant (Jack Gold, 1975) and, after feature roles in the ATV series The Molly Wopsies, Four Idle Hands (both 1976) and Raven (1977), landed the role of Richard in Scum (1977), Alan Clarke’s hardhitting study about borstal life and its vicious circle of violence, a Play For Today that the BBC banned prior to broadcast. He made his film debut in a near reprise of the role, this time as school delinquent Stewart alongside caring Glenda Jackson and fascistic Oliver Reed in The Class of Miss MacMichael (Silvio Narizzano, 1978) and had just completed work in South Africa on Zulu Dawn (Douglas Hickox, 1979) when his mother sent him the Sun advert. With his father a caretaker at King’s Cross Station and his mother an accounts clerk, Daniels was a typical product of the Anna Scher Acting School in Islington, North London, reputed for its finding of ‘raw’ acting talent from the local community and fostering it through an exploration of personal experience: Daniels’ casting would prove a catalyst in its continued reputation as ‘a happy feeding ground for casting directors grubbing for authenticity’ (David Jays, Attitude, June 1996). However, when Daniels appeared for his audition he was at an apparent disadvantage: while filming in South Africa he had moved into a native village as a protest against the living conditions of and a sign of solidarity with his indigenous co-stars, and had been rewarded with a crippling stomach bug. Thin and pallid, his improvisation won him the central role. Though not relevant to the casting, the film would later try to work up a physical resemblance between Daniels and Townshend: a pan onto the bedroom photograph of Pete from Jimmy makes a deliberate – but unconvincing – correlation: at best there is a similarity in the shape of the nose.

Jimmy just missing the look – as usual.

For the leading female role and Jimmy’s love interest, Steph, Roddam and casting director Patsy Pollock chose Leslie Ash, a model whose only film experience had come as the sibling of Rosie Dixon: Night Nurse (Justin Cartwright, 1978). Passed over for the role was the more experienced – if less stereotypically attractive – Toyah Willcox, who auditioned alongside Johnny Rotten. Willcox had progressed from the Birmingham Old Rep Drama School to working as a mime artist with the Ballet Rambert before landing the high profile roles of Mad and then Miranda in Derek Jarman’s Jubilee (1978) and The Tempest (1979). Alongside a burgeoning musical career, Willcox had just completed filming with Katherine Hepburn in George Cukor’s television remake of The Corn is Green (1979). She also possessed determination: on hearing that the role of Monkey remained uncast, Willcox turned up unannounced at Roddam’s office. He offered her there and then an audition of the party scene: a realistic snog with Daniels and the part was hers.

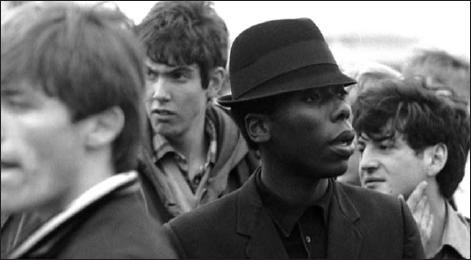

Trevor Laird, friend and fellow Scher school alumnus, came along to the audition with Daniels for moral support. When Townshend saw him, he told Roddam that he was reminded of Winston, one of the Who’s early dealers, so he was signed up and his part written in. Laird resisted Stellman’s overtures to play the part with a West Indian accent – historical accuracy failing to override a determined London identity. Philip Davis, slightly older – and a more convincing lookalike for Roger Daltrey than Daniels is for Townshend – came with several years of television experience while Timothy Spall, fresh from RADA (the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art) gained his first film role as the poker playing projectionist. Garry Cooper, eventually cast as Steph’s boyfriend Pete, had been Roddam’s tentative choice for the Ace Face. He lost the part when Roddam met a 27-year-old former school teacher called Gordon Sumner, just on the verge of breaking through with his three-piece band, The Police. Sting, as he was now known, engaged Roddam in a discussion of the German novelist Herman Hesse (Sting 2003: 311–3). As well as admiring the intelligence and maturity – plus the potential publicity of a star on the cusp – Roddam welcomed the cool attitude Sting exhibited in a deliberately intimidating audition. Daniels’ fellow Scum graduate Ray (then Raymond) Winstone was cast as Jimmy’s old friend – but now a Rocker – Kevin. An amateur boxing champion, Winstone studied acting at the Corona School before being cast by Alan Clarke to play Scum’s central role of borstal alpha male Carlin.

Roddam kept this core together, including peripheral young actors such as John Altman, Gary Holton and Danny Peacock, and further strengthened the acting support with seasoned professionals and well-known faces for adult roles. Cast as Jimmy’s parents were Kate Williams, best known as Jane Booth in the politically incorrect television comedy Love Thy Neighbour (1972–76) and Michael Elphick, a bit part player on films such as Where’s Jack? (James Clavell, 1969) and O Lucky Man (Lindsay Anderson, 1973) but soon to be a regular in prestigious television plays such as Blue Remembered Hills and The Evacuees (both 1979). Comedian Hugh Lloyd, a regular alongside Tony Hancock in Hancock’s Half Hour (1957–61) and Terry Scott in Hugh and I (1962), had a brief role as Jimmy’s line manager Mr. Cale. Benjamin Whitrow, most recognisable as Inspector Braithwaite from the television cop series The Sweeney (1978), played Jimmy’s unsympathetic boss Mr. Fulford, while some real class A category casting came with Sir Jeremy Child, hereditary baronet, as another advertising toff. Eton educated, Child had made his film debut in Privilege (1967), Peter Watkins’ earlier cult dissection of popular music’s messianic dangers.

Perhaps less secure was the casting of John Bindon as boxing promoter and drug-dealer Harry North. Known for his easy movement between the worlds of show-business and crime, Bindon brought an edge of realism and film cultdom, though the presence on set of some of his gangland cohorts made for an uncomfortable atmosphere. Bindon had made a lucky break into films: Ken Loach heard him pontificating in a West London pub and thought him perfect to play the part of Tom alongside Kate Williams in Poor Cow (1966). Thereafter he hit a cult wave when cast as Moody, the henchman to James Fox’s Chas in Performance and gang boss Sid Fletcher in Get Carter. Just prior to filming on Quadrophenia he had stood trial at the Old Bailey for the contract killing of gangland figure Johnny Darke: with the help of testimony from Bob Hoskins, Bindon was acquitted of the charge and left free to add genuine menace and sell fake amphetamines to Jimmy and pals (Brown 1999: 21–3).

NOTHING EVER GOES AS PLANNED

The first two weeks of the shooting schedule were given over to rehearsals and research – a repertory-style preparation, a Mod boot-camp. To build an esprit de corps and to give the cast an understanding of their characters and culture, Roddam and Entwistle introduced them to some first generation Mods, encouraging them to look, listen and learn. Parties in Fulham saw an exchange of both anecdotes and amphetamines while dance lessons above a Soho strip club were taken over by old Mod DJ Jeff Dexter. Period Lambrettas, though, were too expensive to confer on untrained hotheads, so the cast went to Hendon police centre for lessons on modern motorbikes and plentiful jokes about riding. The bonding worked: throughout the eleven-week shoot, this central dirty dozen, plus about forty extras who had all auditioned for main parts but failed, travelled and lodged together. Some of these relationships found their way into the storyline and Roddam was delighted with the results: ‘They were really living it. It was fantastic’ (Sweeney 1997: 69). A Mod ‘method’ had been forged.

Only four days out of the 57 day shooting period were devoted to studio work – the interiors for the house party were filmed at the Lee Studios, Wembley, co-owned by the Who. London locations were centred on old Who haunts such as the dancing at the Goldhawk Road Social Club and Kevin’s attack near Shepherds’ Bush Market. Roddam was keen to film sites for posterity: hence Jimmy and Kevin’s encounters at Porchester public baths, West London, and a pie and mash shop in Dalston, plus Jimmy’s visit to a traditional barber’s shop in Islington. Elsewhere, the gang meet up for pills and pinball at Alfredo’s Café on the Essex Road, Islington; Jimmy’s house lies on the Wells Home Road, Acton; he loses his scooter on a housing estate in Wembley. Even the interior shots of the Brighton Ballroom were shot in a derelict dance hall in Southgate, North London. Further south, the crew detoured to Eastbourne for the first vistas of Brighton and to Lewes Magistrates Court – where Sting pays by cheque.

But on 21 September principal photography began, as the film would, at the climax in Brighton. Initially the local council had refused permission for filming to take place and Roddam had researched pier resorts such as Scarborough and Weston-Super-Mare. But realising that Brighton looked best and would be most faithful to the source album he went back to Baird. In an example of tribal rites at the other end of the social spectrum from Mod, Baird tells of arranging for one of the film’s backers to talk to the friend of a friend, the Chief Superintendent of Police (the term ‘Masonic’ hangs over the entire episode): the latter assured them that it was his say, not the council’s, and that filming could proceed – as long as no laws were broken (Cast & Crew 2005). The first scenes shot were the seaside riots between the Mods and Rockers (and immediately broke the law with over three hundred extras riding without helmets). Three square miles of Brighton were fenced off for two weeks and East Street and Brills Lane, Madeira Drive, Kings Road and even the promenade were dotted with period cars. Scenes were carefully shot in the Beach Café, and outside the Grand Hotel to provide a faithful recreation of the original photo album. (For a full listing of Brighton locations, see Wharton 2002: 80–111.) In addition to the hired extras, hundreds of real Mods and Rockers turned up for the shoot. An outer ring of bodyguards were deployed to ensure no harm came to the main actors, a wise precaution since one extra was hit by an ambulance.

More transport problems almost led to the early demise of lead star and director. Daniels had to drive his scooter along Beachy Head, but got much closer to the edge than intended. Assistant director Ray Corbett made it clear to Daniels that, especially this early in the shoot, he was easily replaceable and on a second run due diligence prevailed (Sweeney 1997: 69).2 Potentially more serious for the film would have been the demise of Roddam. The scene where the scooter flies off the cliff was filmed from a helicopter hired for the afternoon. Some basic miscalculations on flight trajectory meant that the film crew, hovering 150 foot from the cliff edge, were almost hit by the scooter as it flew off the ramp constructed at the cliff edge. Roddam claims to have been more annoyed when he saw the rushes that picked up the tyre tracks of the first take: ‘had it been today, it would have cost you about $500 for a bit of CGI to paint that out’ (Catterall and Wells 2001: 157).

A new generation of Mods, mainly from Barnsley and Preston, all members of clubs reviving ‘old style’ scooter runs to seaside resorts, were recruited at a Scooter rally in Southend and for the first two weeks of filming put up in digs and given a mechanic for their scooters. However, a shortage of Rockers led to Roddam recasting several of these Mods as the enemy: apocryphally one of the Rockers foregrounded in the police van would not show his face to the camera lest friends at home discovered his treachery. Around this committed core were close on two thousand extras, mostly garnered from local adverts and the Brighton Labour Exchange.

And so, to the first call of ‘Action!’, down the slope and onto the beach to the west of the Palace Pier charged the Mods of ‘78, while from the opposite direction came a set of (less authentic) leather boys, with in the middle police on horseback jostling and jumping over them. It was a big beginning, fourteen rehearsed moves with cameras carefully placed. Roddam was pleased with the first take until told by a camera operator that some of the extras playing policemen had been laughing and putting their hats on back to front. So as they reset the scene, Roddam ran over to the Mods and told them that the police – many of them punks – were ruining the shooting, and that they should go for them for real. Though balsa wood deck chairs were again in place, and a second take of the same fourteen moves ensured a rough sense of mass choreography, Roddam’s goading led to scenes of genuine fighting and a realistic recreation of chaos. Cinematographer Brian Tufano, with his instincts as a documentary cameraman to the fore, got in there amidst the flying stones and flying fists, capturing the aggro ‘on the hoof’.

This semi-documentary approach encapsulated Roddam’s working methods: ‘if you set a film up in a naturalistic way, and you get your cast in the mood, you get them into the reality of the situation’ (Catterall and Wells 2001: 155). Several members of the cast testified to its efficacy: ‘There was a sense of not knowing who was public and who was an actor, especially who was a real policeman,’ Toyah Willcox recalled. ‘I remember one grabbing me and I punched and kicked him, and I kicked this car, really going for it. I think I shocked him. He said “We’re only acting!” We were encouraged to be as real as possible’ (Sweeney 1997: 70). It was a strategy employed at all levels of the film, major and minor. When the cast were resting after their beach exertions, Roddam began to film them clandestinely, hoping to catch their genuine bemusement and exhaustion: Laird, noticing the ploy, decided to display disdain for his colleagues, the dealer distant from their territorial spats. It is a momentary scene, but successful through an actor’s sharp eye to the main chance and an intuitive understanding of his character’s relationship to those who buy his pills. It worked equally well in smaller groupings: a short comic scene of high jinks in a chemist’s, with inflated contraceptives and a sniggering exit via the window, was not scripted but emerged from relaxed enactments. When Daniels crashed his scooter into a post van, the stunt driver, whom Roddam recognised as a sensitive individual, was instructed to help Daniels to his feet and just say ‘sorry’: the invective of Daniels’ rant provoked a genuinely shocked reaction. The biter bit? Kate Williams filmed her scene the day after casting and, with no time to learn a script, her assault on Daniels with a rolled up copy of the Daily Mail newspaper was another improvisation. Most significantly, Roddam claims that the attitude of the young cast made him change the ending to his script: ‘When I met all these guys and they were so optimistic, I realised that the idea of death was only some kind of morbid thing that Townshend and I had because we were over thirty. In the end I was glad to have him cast off his job, his parents, his girlfriend and end up free from it all’ (Sweeney 1997: 69). To say nothing of the option for a Quadrophenia 2?

Ferdy: the superior pusher.

Roger Daltrey, living close to Brighton, was the Who member most often on set. Ironically, given the singer’s initial resistance to Meaden’s Mod rebranding of the group, Roddam was aware of Daltrey’s presence ‘like a conscience. He had a sort of Mod idea. If he ever came through it was that he didn’t want to let the Mod thing down’ (NME, 12 May 1979). Townshend was committed to putting together a new set of songs to support and clarify the new narrative thrust of the film – ‘Get Out And Stay Out’, ‘Four Faces’ and ‘Joker James’ resulted. Entwistle was largely preoccupied with editing The Kids Are Alright in America, though he topped and tailed the Quadrophenia filmmaking with his chaperoning of Mod parties and a three-week dubbing period. He worked as musical director and prepared the overall soundtrack.

The strategy of finding and then nurturing young talent was repeated at a musical level. On 12 August 1978 the front page of the New Musical Express had Townshend pointing out in Lord Kitchener mode: the title declared ‘Who Needs You: your chance to star in Quadrophenia’. Inside a full-page ad promoted a contest for a young, unknown English rock band to audition to appear in the movie version of ‘Quadrophenia’, the winner to be personally selected by the Who and the film’s producers. The prospects reached an irresistible crescendo: ‘Win a part in Quadrophenia!! Fame!! Groupies!! Polydor recording contract!! Instant Stardom!! Money!! Drugs!! Speakeasy membership included!!’ The competition would be won by Cross Section, who Daltrey felt fitted the Mod image perfectly, mainly because – clearly in spite of the advert – they ‘projected such an innocence’ (www.seamonkeys.tripod.com/discography/id7.html). They appear early in the film at the Goldhawk Road Social Club playing Tommy Tucker’s Mod classic ‘Hi Heel Sneakers’ and just a few bars of ‘Dimples’ before their moment in the spotlight fades away. In November Entwistle travelled to Los Angeles to negotiate with MCA the inclusion of half of the Who’s original recording of ‘Quadrophenia’ on the Polydor soundtrack for the film. In mid-December, principal photography for the film concluded.

During the editing process, entrusted to yet another debutant, Sean Barton, at least four scenes were omitted – though still images were released on the short documentary accompanying the 1997 UK video. Most notable was the deletion of almost all of the dialogue of the Ace Face, including two extended scenes from the police van and one of all the Mods meeting up on their scooters prior to their descent on Brighton. The reason given for removing all of Ace Face’s dialogue was that Sting and the producers agreed that this ruined the ‘mysterious’ character that he was playing and also took the focus off the main protagonist, Jimmy. Though not stated, it also protected the then limited acting experience of Sting from over-exposure.

On 14 May 1979 both The Kids Are Alright and Quadrophenia were premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. To mark the occasion, the Who performed, Kenney Jones making his concert debut on drums. Quadrophenia received its British premiere on 16 August at the Plaza cinema in London’s West End. Cast members legally old enough and crew attended, as did the Who, while four score members of the Scooter Club of Great Britain, dressed in Mod gear for the occasion, blocked off Lower Regent Street. The film opened in Canada at the Toronto Film Festival on 14 September and in the United States on 2 November. For the Japanese release it was retitled The Pain of Living.