THE SECRET TO ME ISN’T FLOWN LIKE A FLAG

In the United States Quadrophenia was never a box-office success and its initial core followers were the cognoscenti of the Who back catalogue. Its ‘group’ cult status grew through early exhibition on the midnight movie circuit, ‘probably the phenomenon most associated with cult movie fandom’ (Jancovich 2003: 3). Critics such as Barry Keith Grant have suggested that the ‘midnight screening’ was central to the construction of the cult film as transgressive, as anti-respectability and as ‘against the logic of “prime-time” exhibition’ (2000: 19), while Joanne Hollows has emphasised how the sites of such screenings, ‘often screened in porn cinemas or in picture-houses that existed in close proximity to them’, re-enforce cult movie-going as a male preserve: ‘the sleaze of the cinema … works to confirm the figure of the cult fan as a (frequently heterosexual) “manly adventurer” who sets out into the urban wilderness, a position less open to women’ (2003: 41). The importance of the spatial organisation of cult movie fandom for America is supported by Gregory A. Waller’s pioneering investigations of the midnight movie booking schedules for Lexington, Kentucky between 1980–85, a market ‘rather typical, especially for Middle America during this period’ (1991: 168). Waller states that the Kentucky Theater was then situated next to an X-rated adult cinema and a gay bar: ‘so as an afterhours site it was obviously less mundane and “legitimate” – and thus by certain standards more appealing – than any mall or shopping centre’ (1991: 170). Turning to the screen itself, Waller finds that rock movies were a staple ingredient of such late showings, with the Who, a cult within a cult, ‘something of a midnight movie mainstay’ since The Kids Are Alright, Tommy, and Quadrophenia regularly featured (1991: 176). The latter film’s coupling with other cult fare especially helped it to find an audience: author Danny Peary happened on Quadrophenia ‘only because it was the regular feature that preceded Midnight Movie The Rocky Horror Picture Show’ (Jim Sharman, 1975) (1984: 134).

Content as well as context is important, nonetheless. Cult movie fandom not only operates around, but frequently focuses on specific performances of masculinity, though one could place Quadrophenia among the less gendered textual parameters Waller proposes for midnight movies ‘that operate reflexively to address the conditions of midnight movie going, including images of what it means to participate in the “social experience” of a collective audience and to be partygoers’. Such films can foreground excess in structure and content: the latter, particularly relevant to Quadrophenia, includes ‘sexual escapades and drug subculture; the oppositional spirit expressed in the films, be it overt criticism of social institutions and cultural priorities or the ridiculing of adult authority figures’ (1991: 180). Finally, these screenings of Quadrophenia, linked to England’s Two Tone ska revival, led to a group Mod movement taking root in America in the early eighties, centred in Los Angeles and Orange County and distinct for its racial diversity, encompassing black, white, Hispanic and Asian youths. Never sufficiently popular to dissipate its initial core cult audience, the film has since sedimented in such niche markets: for instance, the American Cinematheque, Los Angeles, which began an annual Mods and Rockers Film Festival in 1999. In truth this is a broad church, with films included either for being ‘mod’ as is modern or ‘rockers’ as in featuring rock music, but Quadrophenia has been a regular feature.

STATEMENTS TO A STRANGER

In the United Kingdom Quadrophenia was the eighth most successful picture of 1979 at the UK box-office, grossing over £36,000 in its first week in the capital. Its success encouraged Levi’s to instigate a 1979 advertising campaign using a still of Jimmy on his scooter (from the scene where he visits Dave at the council tip); the by-line read ‘Some things never go out of fashion’. Despite such mainstream incorporation, the strident divisions in reception occasioned by Quadrophenia immediately marked out a cult potential. Reviews were divided along clear generational lines, reinforcing much of the film’s message and fostering early obstinate teenage allegiance. Most effusive in praise were the music press, with Neil Spencer in the New Musical Express coming straight to the point: ‘Like a Mod on speed, let’s not hang about: Quadrophenia is not simply the best British film of ‘79, but probably the best British rock film ever.’ He judged it ‘a film that will help establish reputations, fashions, attitudes, and much more. It is, simply, brilliant’ (NME, 18 August 1979). Young bucks in the national press were in agreement. For Richard Barkley ‘the film is a magnificent achievement in current British cinema, shatteringly honest in intent and stunningly photographed’ (Sunday Express, 19 August, 1979). Nigel Andrews praised ‘one of the most exultantly offbeat British films I can remember’ with its Beachy Head finale ‘as mad, memorable and modernistic as any sequence in recent British film history’ (Financial Times, 17 August 1979). At the other extreme, a range of older critics such as Felix Barker, who had earlier been swept up by the ‘teenage enthusiasm’, ‘charm’ and ‘innocence’ of the Beatles’ films (Evening News, 9 July 1964), were very uneasy with Roddam’s brutal depiction of the Fab Four’s supposed contemporaries. Barker now wrote that ‘Just about everything I dislike is to be found in Quadrophenia. The music is so loud and raucous that there should be a free issue of ear-plugs with every ticket. The film reeks with mindless violence. Without any meaning in their lives, the characters constantly take refuge in nasty vulgarity.’ Barker did admire the way the film uses the Who’s album tracks ‘as background “commentaries” on the actual scenes. It’s an odd way to achieve realism, but it works.’ He concluded, though, that ‘It is a terrible picture’ and regrets how ‘we are going to make money out of washing yesterday’s dirty linen in public’ (Evening News, 16 August 1979). For critical doyenne Margaret Hinxman ‘it depicts an attitude to life which scared the hell out of me’ (Daily Mail, 19 August 1979) while Arthur Thirkell was depressed by ‘a far from pleasant film, filled with a collection of characters so grotty they made me itch’ (Daily Mirror, 17 August 1979). Alexander Walker was one of several (older) critics to misread the ending: Daniels ‘plunges to his death over the cliffs of the South Coast, taking with him lots of stridently orchestrated “sympathy” but no insight into how his times they were a-changing’ and (perversely) decried how ‘the moviemakers’ face is stuck up tight against a squalid little world of dead-end desires’, especially since ‘the feeling that kids are part of a wider society than their own back street is something even the meanest American movie can manage’ (Evening Standard, 16 August, 1979). This search for transatlantic points of comparison, either for copy-cat reactions or contextual lacunae, exacerbated the generational divide: for Spenser the film ‘charts the rock’n’roll teenage wasteland with a compassion, honesty and gritty realism that shrivels the pretensions of all but a tiny handful of so-called “youth culture” movies, British or American’. Whilst admiring the ‘very large chunks of very grim and very joyful reality’ displayed ‘with a panache and speed worthy of the Mod ideal’, Spenser still saw several failings in the film. He found the Bank Holiday riot ‘too violent for ‘64, when street violence hadn’t reached its present level of sophistication’, that ‘track shoes didn’t exist then, that the word “aggro” hadn’t yet come into being, that there wasn’t enough dancing’. Depressingly, he also noted that ‘some of the Mods looked a little old’.

The more high-brow film journals were again less than enamoured. Films and Filming’s end of year honours list – best film Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven – awarded Quadrophenia the accolade of ‘most distasteful film of the year’ (Anon., Films and Filming, 28, 4, January 1980: 29). It initially received equal short shrift in the UK’s most prominent ‘intellectual’ film journal of the time, Sight and Sound. A nine-line response in the final-page mop-up ‘Film Guide’ saw Roddam’s ironically dubbed ‘heavily meaningful portrait of mid-60s England, the era of – in retrospect – rather bogus “gang wars” between Mods and Rockers’ distilled and dismissed with the opinion that ‘unpleasant and frequently unconvincing stereotypes abound’ (Anon., Sight and Sound, 48, 4, Autumn 1979: 268). The following month it garnered a more measured treatment in the same journal as part of Allan T. Sutherland’s retrospective on that year’s Edinburgh Festival. Taking as his theme ‘the heartening range and quality of the British films on show’, Quadrophenia was assessed alongside Ken Loach and Tony Garnett’s Black Jack (1979) and the source of much of Quadrophenia’s acting talent, Alan Clarke’s remake of his BBC-banned Scum. Sutherland noted approvingly how, ‘perhaps bearing in mind the extraordinary self-indulgence of Ken Russell’s film version of Tommy’, Roddam had ‘taken great care to ground his film firmly in accurate reconstruction’. But the film’s strength was also decreed to be its weakness: the primary plot of Jimmy’s ‘growing alienation and eventual suicide’ (sic) is ‘never very forcefully established … perhaps precisely because of the film’s attention to surface detail’. For Sutherland ‘the scene in which Jimmy finally rides his scooter over the cliff proves singularly unmoving’ (Sight and Sound, 49, 1, Winter 1979/80: 15). Most damning of all, Sutherland concluded by pointing out how all three directors, Loach, Clarke and Roddam, had come from a background in television directing. Though understanding how in the current austere cinematic climate such an apprenticeship made financial sense, Sutherland did not find this a healthy situation: ‘the conventions of television drama leave little scope for idiosyncrasy (and considerably less at present than in the more adventurous television climate of the 60s); ratings battles militate against the taking of risks’ (ibid.). Given his earlier relief at an avoidance of Russellian excess, it seems that Roddam was damned if he did, damned if he didn’t.

More muted was the praise afforded to the soundtrack album released by Polydor to coincide with the film (UK 2625 037, US PD2-6235): this featured songs by The Who and Various Artists, and bore a cover photo of Phil Daniels alone and hemmed in down the Brighton alleyway of his earlier finest hour.1 It peaked at number 23 in the British and 46 in the American album charts, on the 5th October and 17th November 1979 respectively.

Entwistle’s new mix still failed to placate Daltrey, who thought it worse than the original. The music critics too were by and large underwhelmed. Neil Spencer’s main reservation concerned the film soundtrack – ‘the music is, ironically, one of the film’s weakest points’. He objected not just to the anachronism of the Who’s numbers, but that ‘most of all, who ever heard of a Mod film without a Tamla Motown record in the soundtrack?’ Tony Stewart regretted that Townshend had originally decided not to revive the musical atmosphere of the Mod era, but surmises that he must have had second thoughts, for the new film material was reminiscent of their sixties output ‘except that it’s not classic stuff, proving that trying to put a snatch of history in a bubble is as futile as trying to bottle a fart’ (NME, 22 September 1979). Apart from ‘Night Train’, ‘Louie Louie’ and ‘Green Onions’, he was also critical of the ‘classic’ songs selected since they suggested that ‘Mod listening was conservative. It was not’. He accepted that the soundtrack should not be considered separately from the film, but ‘when you’re force-fed the whole spurious “Mod” business it’s difficult to treat it in any other way’, and concluded with two definitions: ‘“Mod-ism: n., a euphemism for making money.” And “Quadrophenia” n., four ways of making more money”.’

LP as elegy: a scene to adorn the soundtrack album cover.

I FEEL I’M BEING FOLLOWED

This exploitative element is the central obstacle for the film’s indigenous cult status. Quadrophenia is seen as the catalyst for inciting a substantial Mod revival in 1979: in truth the nationwide release of the film took an already burgeoning subculture and pushed it mainstream.2 In doing so it led to a schism with my former idol Paul Weller. The Jam’s ambiguously punning album title of late 1978, ‘All Mod Cons’, had sounded a note of caution, and Weller would never fully endorse the movement he helped to popularise, perhaps aware of its intrinsically ersatz nature, and no doubt wary of staking his allegiance to any single and reductive trend. When ‘Going Underground’, the group’s tenth single went straight to number one in May 1980, it was a commercial peak and a creative watershed. Weller, never one to stay still, would explore new dance music directions less to my own tastes, while I watched and listened as others battled to inherit the unclaimed Mod revival crown.3 The New Musical Express had sensed this might be the new scene and the front cover of 14 April 1979 bore the image of a scooter-riding Mod from the Bank Holiday riots of fifteen years earlier. This ‘Mod special’ devoted four pages to the lives of original or core modernists, but also two pages were given over to the new wave of Mods. There, dominating the article were two photos from the ‘the Who’s forthcoming Quadrophenia movie’ captioned ‘Blood and Bluebeat Hats’ and ‘Life on a LI’.

It also bore a first advert for the Bridge House pub in Canning Town and its regular Mod nights. It was there that the Purple Hearts from Essex built up a reputation, consolidated by spots at the Saturday night Mecca for the Mod revival, the Wellington pub in Waterloo. They signed to Fiction, the label run through Polydor by Chris Parry, the man who signed the Jam, and released their debut album in May 1978, the well-respected ‘Millions Like Us’. Their next release, in March 1980, would, tellingly, be called ‘Jimmy’. The Chords followed a similar progression, working round Deptford, and then the Wellington where Weller heard them and arranged a support spot to the Jam. After signing to Polydor, they just made the top 40 in February 1980 with their second single ‘Maybe Tomorrow’, considered the Mod revival’s very own ‘My Generation’. Both, though, were no match for another Bridge House band, Secret Affair, more assured and less ashamed to ride the Quadrophenia-inspired new wave of Mod. Reconstituted from a power pop band called the New Hearts, they soon had a fanatical following known as the Glory Boys. Secret Affair made an instant impact on the national consciousness with their rabble-rousing debut single ‘Time For Action’ which entered the chart on 1 September 1979, climbed to number 13 and sold close to 200,00 copies in a ten-week chart life. All combined for a March of the Mods nationwide tour, heralded on the front page of Melody Maker 25 August 1979 with the tag ‘the nouveau Mods take the coast road’. It is claimed that the opening of Quadrophenia was brought forward to coincide with this March of the Mods tour, the distributors now fearing they would miss out on a Mod revival after first labouring under the delusion that they would create it (Chris Bohn, Melody Maker, 25 August 1979).

Already, though, the pendulum was swinging and a ‘Plan B’ (the first single by the amphetamine-titled Dexy’s Midnight Runners) was needed. The lower reaches of the charts were now clogged with sub-Who combos: suddenly every other retail outlet seemed to stock high and sell dear industrial strength parkas and Union Jack jackets. Those in the know knew the need for a quick killing, for of all subcultures Mod is perhaps the least amenable to the oxygen of publicity. It has always been best cherished as a secret affair, its value residing in its elitism and esotericism. As such the success of Quadrophenia was a mixed blessing, a Ready, Steady, Go! for the seventies, attracting a new, dilettante following, but instantly alienating the hardcore. It did for groups like The Chords, seemingly on the up but knocked flat by the success of Roddam’s film.4 The swift backlash was certainly not good news for latecomers to the scene, ever-increasing numbers of blatantly named bandwagon jumpers competing for a market that had already barred them from the play list. The Mods, The Scooters, Squire, Beggar and Small Hours all featured on the live ‘Bridge House Mods Mayday’ album of 1979, yet all missed the target. The Lambrettas did at least have a Brighton provenance, incurred the wrath of The Sun with a single called ‘Page 3’, and hit the top 20 in June 1980 with the anthemic ‘D-a-a-ance’, but their highest chart position, the revivalist zenith of number seven, had come in March with a Pete Waterman-produced cover of ‘Poison Ivy’. Even more desperately, the Merton Parkas (featuring, on keyboards, Weller’s future Style Council partner Mick Talbot) had scraped into the top 40 in August 1979 with ‘You Need Wheels’ – record sales boosted by the special offer of a free sew-on parka patch.5

Along with the iconography, though, the new Mods also rediscovered the violence. The Glory Boys, keyhole logo and ‘Secret Affair’ tattooed on their arms, would travel around the country, not so much to follow the music, but to pick a fight with anyone willing to engage them, usually other, northern Mods. This brings up a less salubrious element in Quadrophenia’s active communal following, one witnessed at my own first viewing of the film. Part of Quadrophenia’s appeal is that its story world passes beyond the screen into a real historical hinterland of adolescent aggression. In a discussion of Heavenly Creatures (Peter Jackson, 1994), another cult film centred on a true event, Harmony Wu has pointed out that diehard fans seem compelled to reckon with the historical matter on which the film is based – in this case the teenage murder of a parent (2003: 100). The same holds true for Quadrophenia except that ‘diegetic immersion’ here is not simply a matter of subsuming oneself in Roddam’s skilful mise-en-scène or revelling in Daniels’ riveting performance. Indeed, without opening the whole debate of cinema and violence, there is a case for labelling certain elements of fan behaviour ‘diegetic imitation’. On August Bank Holiday 1981, while the Jam’s ‘Funeral Pyre’ rode high in the top five, backed by a cover of the Who’s ‘Disguises’, the southern seaside riots happened all over again. This time the battle lines were drawn between the Mods and their earlier offshoot, the Skinheads. Catterall and Wells quote from Frix, ‘the Southern Skin’ warning the Brighton Evening Argus of trouble ahead: ‘word is out that a load of Mods from Scarborough are coming down here. The only reason they come here is because of that film Quadrophenia. All these young kids just copied it to follow the trend. They go around with their scooters and tonic trousers like something out of Quadrophenia and they have the nerve to take the rise out of us’ (2001: 160).

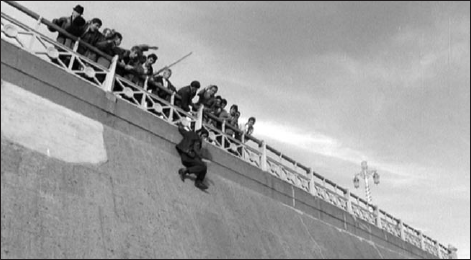

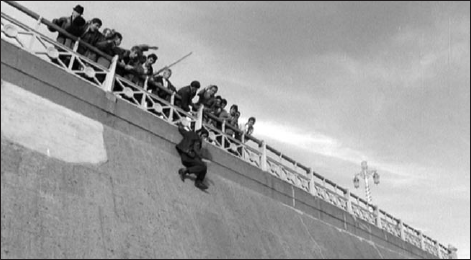

Control those kids: newspaper reconstruction newly minted for the 1990s.

History, though, is not always forced to repeat itself. If Frix knew there was going to be trouble that summer, so too did the heavily funded forces of Thatcher’s Britain and this was never going to be a re-run of Quadrophenia’s orgiastic thrashing of a bemused, uncertain police force. When a first petrol bomb was launched the police swiftly rounded up 300 Mods and marched them to an open, lawned section of the promenade. There the Phil Daniels wannabes were told to remove their shoes, jackets and crash helmets, before being made to lie face down on the grass. They were kept like this for over six hours as police megaphones constantly blared out strict orders not to move or talk.

In its new, media-savvy incarnation, Sussex Police headquarters in Lewes were determined to bat back any press comparisons with the 1964 riots. When the law refused to cooperate with their inquiries, the Brighton Evening Argus turned to lecturer, now Professor Stanley Cohen, author of the earlier Mods versus Rockers case study. Cohen too saw this as different in kind, not just degree. The events of 1981 had scant resemblance to a newly affluent youth revelling in the freedom from National Service. Instead, ‘the issue is a massively deep one, stretching into unemployment and urban tension of the kind that helped cause the Toxteth and Brixton riots’. Two years before the Miners’ strike, Cohen also sounded a note of caution on how the fighting had been quashed second time around: ‘It would appear the police are taking on the role of the courts, deciding on punitive action before anyone has even been before a magistrate or a sentence has been passed.’ It was not a view shared by Magistrate Roy Long who, without the soundbite of a ‘Sawdust Caesar’, still justified the imposition of fiercely stringent fines: ‘when a gang of 300 youths come to this town and act like animals they must be expected to be treated as such’ (Catterall and Wells 2001: 160).7

Along with thwarted patch rivalries, Quadrophenia helped to propagate a print revival. Alan Fletcher, story consultant on the film, released a novelisation of Quadrophenia, published by Corgi Press with an air-brushed scooter on the front cover. The book gives more space to the female characters and expands on themes only glimpsed in the film, for example the mutual loathing of Jimmy and his sister Yvonne, and Monkey’s sexual promiscuity. Fletcher has subsequently published a further three Mod novels, Brummel’s Last Riff, concerning a trio of sixties Mods, The Learning Curve and The Blue Millionaire. The ‘youthsploitation’ fiction of the New English Library featured Richard Allen’s series of youth cult novels which, impressively responsive to the shifts from Skins to Suedeheads to Smoothies, focused on Plainstow ‘knuckle boy’ Joe Hawkins, ‘a little bundle of deviance waiting for subcultural shifts to give him new life’ (Hunt 1998: 76). The series began with Skinhead (1970) and ended with his illegitimate son the hero of Mod Rule (1980), a less persuasive embodiment of the new soul rebels. Finally, May 2011 saw the publication of Peter Meadows’ To Be Someone: Jimmy’s Story Continues, reputedly with Townshend’s permission after the author submitted an early draft. Picking up at the conclusion to the album rather than the film – and changing almost all character names (Steph becomes Bunny, Monkey becomes Judy) in order to circumvent copyright issues with The Who Films – Meadows’ novel takes Jimmy through and beyond the Mod revival period – the Jam get an honourable mention – as he works his way up / down to a drug dealing, cocaine smuggling Guy Ritchie style wannabe ‘gangsta’.

I’M SEEING DOUBLE

Plans for a film sequel to Quadrophenia were often discussed. That they have not (yet) come to fruition hardly matters and has perhaps even helped: cult films often leave narrative ‘loose ends’ that ‘give viewers the freedom of speculating on the story’ (Mathijs and Mendik 2008: 3). Once those initial misreadings of suicide were corrected, fans could indulge in their own imaginative narratives of the older Jimmy. I figured, without too much conviction and far different to Meadows, that he would have taken the ‘soft’ Mod route into hippydom and headed off to India. Roddam himself has offered more authoritative speculations for Jimmy: the first is transgressive, hoping ‘he’s become liberated enough to become someone special’. But he works down to more mundane life paths: ‘in advertising proper? A voter for the BNP? Part of me thinks he might have become an “ordinary Joe” with a big smoking habit and a beer gut’ (DVD documentary 2006). This final option, where Jimmy ends up like his father, proposes a life that is (by way of gender and upbringing) predetermined, his youthful gesture habitual. It hypothesises a generational duplicity realised in That’ll Be the Day; it also loosely fits with Pete Townshend’s solo concept album and accompanying video ‘White City: A Novel’ which, released in November 1985, employed another ‘Jimmy’, a crisis-ridden thirty-something stuck in a council flat in Townshend’s native West London: an early track has a Mod resonance in its title ‘Face the Face’.

For those happy to stay with the teenage Jimmy, in the spring of 1986 Quadrophenia was released on video, through Channel 5 video and Polygram, with an 18 certificate and a grainy washed-out print. This coming of video marked an important change in viewing habits: it accelerated a waning of the midnight movie circuit in the States, whilst in Britain the accessibility of domestic, solitary access signalled the inception of an indigenous cult revival.

Fast forward to the early 1990s and the signifiers of ‘Quod Mod’ built to a second coming. While the media majority were in thrall to the sound of Seattle and the baggy black t-shirt, another backlash began slowly in the upstairs room of the Laurel Tree pub in Camden at a weekend club night entitled (after the film the Who nearly made) ‘Blow Up’. Here again one can witness the dynamic nature of bricolage with an indie variant on the Mod ethic: by 1994, the scene attracted press attention as ‘in’ drinking venues such as the ‘The Good Mixer’ were lauded and, as ever, the hardcore moved on. Opportunistic bands like Menswear and The Bluetones were signed up, and the indigenous music shifted from the ecstasy-charged, Chicago house throb of Madchester back again to the shiny melody and narrative of the Small Faces, the Kinks and the Who. Barely a month before the suicide of Kurt Cobain in April 1994, a Fred Perry attired Blur released ‘Girls and Boys’ and hit number five in the UK charts. Quadrophenia was one of the films of which group members Damon Albarn and Graham Coxon were most fond (Harris 2003: 44) and, supportive of the film where Weller had been dismissive, they would prove the conduit to the second wave Mod revival. Blur’s September single ‘Parklife’, with Phil Daniels guesting on voice and video, paid due homage to Mod influences and hit the top ten. Here was Mod pop revived as Britpop, and against Blur came Oasis: except that again, for all the press hype pitching the Northern working-class versus middle-class art school Londoners, the similarities between the two groups were, especially in retrospect, much more significant. Signed to Creation Records by life-long Mod Alan McGee, Oasis were ‘cool’ incarnate, Noel Gallagher’s songwriting credentials enhanced by his much-vaunted friendship with Paul Weller, and Mod chic again became the nation’s look and outlook. In magazines like Loaded and Heat Liam Gallagher look-alikes modelled fishtail parkas and Hush Puppies. The cover of Melody Maker for 19 November 1994 showed, under the heading ‘Touched by the Hand of Mod’, a dozen impeccably attired girls and boys standing behind three carefully positioned Vespas: inside an eight-page special investigated ‘The New Mod Generation’. Alongside advice on where to be seen, what to wear and where to buy it, the special supplement interviewed ‘the new ace faces of the New Mod Squad’, Menswear, Thruman and Mantaray. In the centre spread, a ‘Rebellious Jukebox’ special, ‘Mod icon and star of the Who’s Quadrophenia movie, Phil “Parklife” Daniels talks about the records that put a shine on his scooter’.

Mod was again transmogrified, though opinions differ as to the merits of such endless recursion. For an essentialist such as Jon Savage ‘like a Xerox of a Xerox, the image gets more and more degraded each time. A narrowly revisionist image of the past is being recruited to block from use in the present that past’s true powers and complexities, its alternatives and choices’ (1997: 16). I felt more in tune with Paul Moody, for whom this regeneration was final ‘proof that Mod could mutate into a reflection of contemporary street culture and yet still retain its vital characteristics: confidence, defiance and an appreciation of a nice pair of shoes, all wrapped up in a cocksure bravado traceable all the way back to original “tacky herbert” Jimmy Cooper’ (2005: 135).

Amidst this Mod revival mark two, MCA continued its Who reissue series. This time Daltrey and Townshend were both involved in remastering and remixing the original 1973 ‘Quadrophenia’ album, and the new 1996 release was praised for bringing out musical features such as the guitar thrust on ‘The Real Me’. Their pleasure at the result was one of the catalysts for ‘Quadrophenia’ to rise again. In April of that year, as Oasis’s ‘Don’t Look Back In Anger’ beat Blur’s ‘Stereotypes’ to the top of the UK charts, it was announced that the members of the Who would be part of the biggest rock concert in London for over 20 years. Just backdated? Following persuasion and compromise by Townshend on the script and staging – Daltrey now assumed the director’s chair – on 29 June 1996 both men plus Entwistle, still significantly billed under their separate names, performed the entirety of ‘Quadrophenia’ live at the Masters of Music Concert for the Prince’s Trust at Hyde Park, London before an audience estimated at between 300 and 500 thousand. Phil Daniels narrated, former Young Ones comic actor Ade Edmundson played the Bell Boy, News At Ten stalwart (and later Sir) Trevor McDonald added authenticity to reading the news, and actor-comedian Stephen Fry played the Hotel Manager. Now was the time for ‘Quadrophenia’ to go post-(M)odern: Glam Rock entered the equation with Gary Glitter starring as the bouffant Godfather, prog rock contributed with Dave Gilmour of Pink Floyd playing electric guitar, while Ringo Starr’s son, Zak Starkey, sat in on drums, moving him towards the permanent role of Who drummer. Except for its maiden performance at Stoke back in October 1973, this was the first time ‘Quadrophenia’ had been performed live in its entirety. Preceded by Alanis Morissette and Bob Dylan, followed by Eric Clapton, the revival of Jimmy Cooper formed the centrepiece of an event to raise money for Prince Charles’ charity for disadvantaged young people. The performance prompted a brief return of the ‘Quadrophenia’ album to the UK charts, peaking in early July at number 47. On 16 July the resurrected rock opera moved to Madison Square Garden in New York for what was announced to be their only US performance: former punk and Generation X front man Billy Idol now played the silver-suited Mod. In fact a further five sell-out shows ensued, with the performance of 18 July broadcast live on Westwood One Radio and thereafter widely available on bootleg. Alerted to the piece’s popular acceptance, an extensive 25-date US tour ran from 13 October to 19 November, with the Who’s name now back on the billboards. The film version also came back into view as the live narrator, thought to be slowing down the pace of the show, was replaced by a series of filmed vignettes played between the songs and projected onto a large JumboTron screen behind the band. This film, directed by Daltrey, now featured relative newcomer Alex Langdon as Jimmy, speaking his lines slowly and with clear enunciation to allow for the time-lapse echo in big venues and to give American audiences a chance of understanding a London accent. His ‘spell-it-out’ narration was accompanied by newly shot and newsreel footage, but prominent scenes from Roddam’s Quadrophenia were also intercut and so, in what amounted to a series of trailer ads, the 1979 film joined the group on a multimedia concert tour of Europe from early April to a Wembley Arena date on 18 May and then on to North America from 19 July to 16 August 1997, now with P.J. Proby and Ben Waters.8

I’M OUT ON THE STREET AGAIN

The momentum was again behind the Mod movers and the Who’s rock opera and so, with Union Jacks once more bedecking jackets and guitars, Quadrophenia was re-released cinematically in the UK on 31 January 1997, newly subtitled ‘A Way of Life’ and newly awarded, to press consternation, a 15 certificate. This change is significant, opening the film to a teenage audience denied first time round and facilitating a fresh cult following. Other sections of society were also now more welcoming. To publicise the re-release Brighton was again invaded on 29 January, this time by the press and cast members who boarded the ‘Quadrophenia Express’ at Victoria Station, London to be met at Brighton by a prepared gathering of Mods and ad-men for the new premiere. This time the Mayor was also in attendance and made an introductory speech: explicitly incorporated, the film was now clearly good for business. It prompted another wave of extensive media coverage, plus another pretext for the latest soul stylists to slip away quietly. Laudatory cast and crew interviews featured in the new popular film journals and in Loaded magazine: high / low art dichotomies remained as the two-page retrospective from Jon Savage in Sight and Sound savaged the film and its faux-Mod trappings. The positive dominated: Charlotte O’Sullivan caught the level of appreciation shared by several reviews when she wrote that ‘this is one of the best portraits we have of this frustrated little island. Too honest to be upbeat, too exciting to be bleak, even second time round it’s unmissable’ (Time Out, 29 January 1997). The point of common comparison was not now Rebel Without A Cause but Danny Boyle’s international success of 1996, Trainspotting, ‘the only other film about British youth culture in living memory that isn’t completely and utterly embarrassing’ (Gay Times, February 1997). ‘If you can’t follow the off-the-wall storyline … why not think of Quadrophenia as a retro Trainspotting?’ advised Danny Wallace (Total Film, 1 February 1997). Nick Hasted declined, exploring instead ‘the doomed energies that give Quadrophenia its lasting power and prevent it from being simply an off-the-peg lifestyle movie for the Trainspotting generation’ (Independent, 30 January 1997). There was justification to compare the camerawork of the two films since Quadrophenia had just been re-graded for its cinema release by Brian Tufano, now Boyle’s cinematographer, whilst in interviews Roddam was happy to accept Quadrophenia as a direct predecessor for content: ‘If you look at the two in terms of subject matter they’re practically the same – sex and drugs and trouble with parents, they’re still the eternal problems of growing up’ (NME, 29 January 1997). Alongside associations with Renton and company, a critical common denominator concerned ‘the casting of a minor but pivotal part: was 1979 really so long ago that audiences could accept the utterly preposterous notion of Sting playing a guru of cool? They were such innocent times’ (Independent, 14 February 1997). In spite of ‘super-Mod Ace Face (Sting) dancing like a paranoid chicken’ (Time Out), a Universal region 2 DVD release followed in the Summer of 1999: this added an 8 minute montage but kept the poor quality print and clipped 4:3 format and reverted to the 18 certificate. A Rhino special edition US DVD release in September 2001 had a remastered and matted widescreen transfer, but had scenes cut and an indifferent collection of extra features.

All these platforms fed Mod iconography further into youth subcultures: indeed, Quadrophenia can be seen to bookend the club culture of the nineties with its ‘intertextual frames’.9 In 1992 Camden ‘baggy band’ Flowered Up reached the top twenty with their 13-minute single ‘Weekender’. The song sampled dialogue from the film, ending with Jimmy’s cherished resignation speech when he tells the bemused Fulford where he can shove ‘that mail and that franking machine and all that other rubbish I have to go about with’. Together with the accompanying video (by W.I.Z.), centring on images of scooters, bath tubs, girls at supermarket check outs, and its narrative arc of ecstasy-fuelled clubbing and inevitable comedown, the work is a conscious melding of Mod with its latest hedonistic offspring. When later, in Human Traffic (Justin Kerrigan, 1999), Jez intones his mantra that ‘the weekend has landed: all that exists now is clubs, drugs, pubs and parties’, pride of place on his poster-filled bedroom wall, above icons of hipness like Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986), Drugstore Cowboy (Gus Van Sant, 1989) and Clerks (Kevin Smith, 1994) is the group pose from Quadrophenia – full colour Quod, naturally. Plot lines again chime: a tale of the agony and Ecstasy of five friends in Cardiff clubland, Human Traffic also concludes with one member, Moff, realising the emptiness of his life and walking away from the group.10

The film’s re-rerelease and concurrent new Mod revival fed again into other media. It is difficult to imagine a less clean-cut Mod image than the grunge-inspired skateboard culture, but the Mod target icon became central to the popular Squadrophenia board, and a Squadrophenia DVD release (2004) of the skateboard collective Death Squad apes the 1998 4Front video release featuring a group shot on the cover with a target icon behind them. Quadrophenia served as a catalyst for Howard Baker’s revisionist novel Sawdust Caesar: The Pioneers of Youth Rebellion (1999). Pulp fiction in the tradition of Richard Allen, its central character, perversely named Tommy, is of the hard Mod variety – a participant in the early Mod versus Rocker Bank Holiday battles but who boasts how ‘the Who began to promote themselves as Mod icons and we knew it was time to move on’. Tommy moves on (as a ‘Smoothie’) to a life of petty crime.11 The original album too profited from this symbiotic rebirth. On 5 January 2001, VH1 cable music channel placed ‘Quadrophenia’ at number 86 in the top 100 rock albums, while the editors of Rolling Stone put it at number 90 in their rock poll published on 17 October, 2002. In December 2003 they voted ‘Quadrophenia’ the 266th greatest album of all time. On March 22 2005 BBC4 broadcast, as part of its Cast & Crew series, a reunion of Roddam, Stellman, Tufano, Barton and Baird who reminisced about the making and meaning of Quadrophenia.12 Kirsty Walk introduced the film as, 25 years on, still ‘perhaps the only movie ever seriously to get to grips with British youth culture’. In August 2006, Universal released an improved Region 2 two-disc special edition on DVD: the film, again presented in a matted widescreen version rather than the original full screen, was digitally remastered and included a fresh commentary by Franc Roddam, Phil Daniels and Leslie Ash while a bonus disc featured an hour-long documentary and a featurette with Roddam discussing the locations. A fourth, definitive DVD – and first Blu-ray – release came in August 2012 from the prestigious US Criterion Collection. This ‘director approved special edition’ contained a raft of features including on-set archive footage, behind-the-scenes photographs, a fresh audio commentary with Roddam and Tufano and a highly publicised all-new 5.1 surround-sound mix, supervised by Townshend and Daltrey: here finally was the multi-channel mix that had proven so elusive back in 1973.

Intertextual frames have grown apace. Perhaps the proof of a cast-iron cult status came when, on 5 and 6 April 2008, the Holiday Inn on Brighton Seafront hosted ‘Target 30’, the first Quadrophenia film convention: most of the main players – minus Sting and Leslie Ash – attended.13 A play version, initially developed with the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama at the Sherman Theatre, Cardiff in February 2007, undertook a UK tour starting on 9 May 2009 in Plymouth. This was written by Jeff Young who had previously helped Townshend resurrect Lifehouse in a BBC Radio 3 adaptation; both projects were directed by Tom Critchley, a regular partner for Townshend since developing ‘Psychoderelict’ in 1998 as a (yet unrealised) Broadway musical. However, the breadth of casting for this stage version, with four Jimmys on stage at once, failed to secure significant depth of characterisation while the sung-through nature of the piece proved that, unlike ‘Tommy’, the musical narrative alone was insufficient for a coherent spectacle, even though several key scenes from Roddam’s celluloid version were played out in mime. For Roz Laws ‘Where the production falls down is in its far-from-clear story. Those unfamiliar with the 1979 film may well be all at sea’ (Birmingham Evening Mail, 20 May 2009). It might, though, have sent members of its bemused audience back to the film for orientation.

Or back to the band itself. Starting in November 2012, one year on from the four-CD deluxe ‘Director’s Cut’ release of ‘Quadrophenia’, and over two years on from a 30 March 2010 Teenage Cancer Trust charity show at the Royal Albert Hall, London, where they were assisted by Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder and Kasabian’s Tom Meighan (who wore a silver suit in a nod to Sting’s Ace Face portrayal), the Who undertook a 37-date North American tour entitled ‘Quadrophenia and More’. For this, the fourth time in which the ‘Quadrophenia’ album had been played in its entirety, the group comprised, alongside Townshend, Daltrey, Zak Starkey and Pete’s brother Simon, bassist Pino Palladino who had replaced Entwistle after his death in 2002. With the staging again entirely entrusted to Daltrey, narration, guest singers or any use of extracts from Roddam’s Quadrophenia were eschewed. Instead, the album was performed straight-through, with video footage now presenting historical montages reflecting the band’s formative years, two intercut solos of Entwistle and Moon and, over the instrumental of ‘The Rock’, a compendium of tumultuous moments from recent history, including Columbine and 9/11 – perhaps an overreach from Daltrey towards Townshend’s essentially inward-looking musical study? (‘Quadraphenic? They’re Bleeding Schizophrenic!’)14 A 14-date European tour followed in June 2013.15

YOU ONLY BECAME WHAT WE MADE YOU

This late ‘flowering’ of associated and alternative versions indicates that, while Quadrophenia had achieved near-immediate cult status in the US, it effectively took the video release of 1986 and DVD re-release of 1997 for it to become a cult film in the UK rather than just a film about a cult. One could cite four contributing elements.

The second Mod revival of the 1990s was evidently the major factor. However, this cult status was heavily fuelled by the media, especially the Loaded magazine culture of the decade. In his study of another cult British film Get Carter Steve Chibnall has pointed out the importance of Loaded magazine, launched in 1994, and the ‘lads’ mags’ such as FHM and Maxim following its lead that were ‘infused with nostalgia for a mythic 1970s’ and ‘embedded in a vernacular and class-conscious conception of Englishness that deplored the cultural exclusion of “ordinary” and “everyday” experience’ (2003: 100–1). Moya Luckett sees the Loaded-led rediscovery of films such as Quadrophenia and Get Carter as ‘redefining’ British cinema, working to form ‘an “alternative heritage” that expresses the energy, style and sexuality of British culture, an image fiercely counterposed both to the gentility and restraint of Merchant-Ivory films and Hollywood’ (2000: 88). Luckett cites the conclusion to a Loaded essay, recalling the continued impact of Quadrophenia: ‘The Americans had Grease but we had and still have Quadrophenia and at the end of the day, would you rather be poncing round to ‘Greased Lightning’ going ‘Well-a-well-a-well-ooo’ or would you rather be driving through Sussex on a scooter with no helmet on knowing you’re going to have it off with Leslie Ash in Brighton?’ (Michael Holden, ‘Great moments in life: Watching Quadrophenia’’, Loaded, September 1995: 16). For Luckett, this discourse characterises how British cinema ‘stylises and re-imagines everyday life in ways Hollywood and European Art Cinema cannot’ (2000: 88). Like the magazines that vaunt it, Quadrophenia privileges the working-class quotidian.

Jacinda Read stresses gender before class, arguing that such publications have made political incorrectness and ironic reading part of the subcultural sensibility of young men: ‘political incorrectness is thus seen as, and associated with, the “cool”, “hip” masculinity of the “new lad”’ (2003: 62). This group pressure made the model for cool femininity the figure of the ‘ladette’, a figure who, as the name suggests, was culturally ‘one of the boys’ (Thornton 1995: 104). No doubt this has contributed to the ever-increasing chat-room incredulity that Jimmy goes for Steph instead of ladette Monkey. As argued earlier it may also have informed the opinions of critics like Jon Savage writing in the late nineties in more august journals. The concentration on Quadrophenia by lads mags can support the view that the film is penetrated by seventies values; it also presupposes a continued male spectatorship and a cult of masculinity as much as the masculinity of cult. However, film reception can now be investigated by exploring new technologies which may threaten the sense of distinction and exclusivity on which cult movie fandom depends, yet which nonetheless allow fans across the world to communicate with one another, and even organize themselves as a collective. A search of the Internet Movie Database (IMDb) poll qualifies the assumption that Quadrophenia is an entirely male cult collective. By 1 June 2013, over three-quarters (77.8%) of 8775 voters awarded the film at least seven out of ten, giving an arithmetic mean of 7.5; 13.5 per cent of these voters who declared their sex were women (885 out of 6519) and the male average was only 0.3 higher than the female vote. A predominance of male participants is a familiar and expected feature of such an interactive web exercise but the female demographic is over twice that recorded for Get Carter (Chibnall 2003: 103). Though still significantly in the minority, Quadrophenia has a sizeable female fan-base.

A third factor, perhaps contributing to greater female ‘communion’, concerns changing modes of exhibition. These have altered the organisation of cult movie fandom, and as early as 1986 the film’s video release served to make cult movie fandom much less dependent on place. Snippets of the film shown during the ‘Quadrophenia’ tour of 1996–7 could still be argued to cater to a predominantly male audience but, beginning in 1996, the Stella Artois Screen Tour became one of the UK’s most enjoyable, most ‘cult’ film festivals. Every summer (until 2006) the tour presented a series of well-loved films in real-life, relevant settings. Quadrophenia quickly established itself as a highlight, receiving presentations on Brighton beach before an audience of thousands. This is a much less gendered cinematic space that the sleaze cinemas of early American exhibition: rather it is at one with the rave culture that brings DJs such as Fat Boy Slim to Brighton beach, the offshoot of the Mod legacy that ran through the nineties to Human Traffic. Nonetheless, when I attended on 24 July 2004 there was a male camaraderie to sections of the evening’s active celebration: many of the twenty thousand or so in attendance timed our (purely verbal and virtual back-alley) climaxes perfectly, expelling a loud ‘Ug’ into the sea air along with Jimmy – an act that left us looking just as smug as Jimmy with our ‘cult’ capital and even led to a round of self-congratulatory applause.16 In a similar vein, from the summer of 2013 ‘Quadrophenia Night’ began travelling the UK club circuit, presenting a six-hour theme night with a live band playing hits from the film, a Mod ska soul DJ set and, as its centrepiece, a big-screen presentation of Quadrophenia in its entirety.

Fourthly and finally (or initially) one of the clear retrospective pleasures of watching Quadrophenia is akin to viewing an old school photograph, trying to read back future success into past achievement and attitude. A springboard to lasting success for almost all its main cast and crew, the film is now a repository of extra-diegetic nostalgia, a celluloid variant on the UK television series Before They were Famous (1997–2005). A ‘Who’s Who’ of British visual popular culture, the sheer scale of the film’s legacy merits elaboration.

Smug after ‘ug!’: Jimmy gets the girl.

WHERE HAVE I BEEN?

Quadrophenia afforded director Franc Roddam the capital, both economic and cultural, to move beyond a British cult audience: he had his calling card to Hollywood. After studying close to three hundred script outlines Roddam selected for his American debut Lords of Discipline (1982), a study of racism in the Deep South with a self-elected elite of cadets abusing the Carolina Military Institute’s first black cadet. For Paul Taylor the film does not signal an artistic advance, being ‘more intractably schematic than either Quadrophenia or Dummy, filtering its arid state-of-the-nation concerns through an increasingly transparent military milieu’ (Monthly Film Bulletin, 50, 588–9: 244). In his next film The Bride (1985), a reworking of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein story, Sting brings back to life Jennifer Beals with a lush score from Maurice Jarre and several familiar faces from Quadrophenia in the background. It was not considered a success, Richard Rayner proposing it as ‘perhaps the silliest film of the year’ (Time Out Film Guide 17: 137). Roddam was next invited to film the ‘Liebestod’ from Wagner’s ‘Tristan and Isolde’ for the portmanteau opera film Aria (1987). Often rated the best interpretation, Roddam’s vignette gave Bridget Fonda her first film role alongside James Mathers as a pair of star-crossed lovers. In War Party (1989), an alternate take on the traditional western with a Brat pack cast including Kevin Dillon, a group of wartime re-enactors attempt to stage a centenary anniversary battle between US Cavalry and Blackfeet Indians: reawakened prejudices, personal hostilities and a loaded gun lead to real casualties and a chase after three young and innocent Blackfeet. Roddam was praised for the way he shifted fluidly between depictions of the historical conflict and modern-day tensions: set in the past but pointedly about the present, like Quadrophenia ‘the film commendably refuses to offer an easy, upbeat resolution’ (Colette Maude, Time Out Film Guide 17: 1164). Elsewhere, though, War Party was criticised for being ‘a straightforward celebration of action-movie cliches’ whose ‘supremacist rhetoric might be expected from a director who has an affinity for stories of tribal warfare and / or masculinist rituals’ (Julian Stringer, Monthly Film Bulletin, 58, 687, 1991: 112). His last theatrical venture K2 (1991), concerning a foolhardy attempt on the world’s second highest peak, was dismissed as ‘a lacklustre “boys own” yarn’ (Michael O’Pray, Sight and Sound, 1, 10, 1992: 51). Across this body of work one can locate a broad auteurist preoccupation with internecine youth groupings, homo-erotic buddy relationships, the inevitability of human failure and set-piece historical recreations. Roddam then moved into television film, again pinpointing the grand gesture in Moby Dick (1998) and Cleopatra (1999). He enjoyed fuller success away from the camera, as the creator of comic investigations of working-class working life, first with ITV’s Auf Wiedersehen, Pet (1983–86), relaying the misadventures of a gang of British workmen on a Dusseldorf building site, followed by BBC’s Making Out (1989–91), a distaff variant set in a Manchester factory. Latterly he was executive producer for the six-part updating of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (2003). His greatest success, though, was an aspirational middle-class initiative, as the deviser / executive producer of the cookery competition Masterchef (1990–2001) and its subsequent Celebrity, Professional, Junior and Live spin-offs.

Martin Stellman went on to write Babylon (1980) with director Franco Rosso, an investigation, through Brinsley Forde’s garage mechanic trying to win a sound-system contest, of the trials and tribulations of young blacks in London. Stellman moved to the less youth-oriented Defence of the Realm (David Drury, 1985) for his first solo screenplay before returning to the black experience when co-writing and directing For Queen and Country (1988) where Falklands War veteran Denzil Washington returns to his grim South London council estate only to be told he is no longer a British citizen. Much later than Roddam, Stellman encountered muted Hollywood success as the writer of The Interpreter (Sydney Pollack, 2005). Brian Tufano established himself as one of the UK’s leading directors of photography, working again with Roddam and then most famously with Danny Boyle, first on the BBC series Mr. Wroe’s Virgins (1993) and then his films Shallow Grave (1994), Trainspotting (1996) and A Life Less Ordinary (1997). This, plus work on British successes such as East Is East (Damien O’Donnell, 1999) and Billy Elliott (Stephen Daldry, 2000), helped him to receive in 2001 the BAFTA award for Outstanding Contribution to Film and Television. He has continued to train his camera on London youth with Noel Clarke’s Kidulthood (2006) and its sequel Adulthood (2008).

And the fledgling stars of Quadrophenia? Their futures lay in music, musicals, television, and the cinematic holy trinity of British working-class life, Blair, Clarke and Leigh. Neil Jeffries, reviewing the 1997 cinematic re-release of Quadrophenia, was full of praise for the impressive period detail, the powerful action, the streetwise script, the uplifting music and the superb pacing. ‘Best of all though is the cast, almost every one of them now a familiar face’ (Empire, 92, 1997: 38). The film was correct in that its (supposedly) most charismatic character, the Ace Face Sting, would achieve the greatest stardom as lead singer of the Police, before going solo, gaining even greater success and using his profile to raise ecological awareness. With Andy Summers and Stuart Copeland, Sting and the Police, nominally punk rock but far too accomplished musically, hit the big time between the shooting and release of Quadrophenia, first with the re-released ‘Roxanne’ hitting the top 20 in May 1979 to be followed by number one successes with ‘Message in a Bottle’ in October and ‘Walking on the Moon’ two months later, each featuring the group’s distinctive ‘white reggae’ rhythms. This burgeoning pop fame helped to promote the film in media features: the osmosis can be seen on the back cover of the Police’s debut album ‘Outlandos d’Amour’ (1978) which features a still of Sting as Ace Face in the court scene from Quadrophenia. Thereafter, the group hit global success, effortlessly conquering Europe, Asia and America with ‘Zenyatta Mondatta’ while five successive albums topped the UK charts between 1979 and 1986. While contributing to the majority of Police songs, and all their hit singles, Sting continued to act, starring next with Benjamin Whitrow as the devil Martin Taylor in Richard Loncraine’s film remake of Dennis Potter’s BBC-banned Brimstone and Treacle (1982). His celluloid career survived the role of Feyd-Rautha in David Lynch’s cataclysmic Dune (1984) to team up again the following year with Roddam as Doctor Frankenstein in The Bride. Though less critically feted, regular film outings have dovetailed with Sting’s solo career singing schedules, notably a back-to-roots role as Newcastle jazz-club owner Finney in Mike Figgis’s debut feature Stormy Monday (1988) and a cameo as JD in Guy Ritchie’s debut success Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1998).

Ray Winstone has proven to be arguably the biggest acting success. He worked again with Daniels as Tony in Les Blair’s crime drama Number One (1984), a film starring pop stars Bob Geldof and Ian Dury. Constant film and theatre work thereafter, including the part of Sam in Mike Leigh’s Ladybird, Ladybird (1994), led to a late flowering in strong realist roles such as Ray in Nil By Mouth (Gary Oldman, 1997), Dave in Face (Antonia Bird, 1998), Dad in The WarZone (Tim Roth, 1999) and Gary Dove in Sexy Beast (Jonathan Glazer, 2000). He has recently moved to Hollywood star status in The Departed (Martin Scorsese, 2006), Beowulf (Robert Zemeckis, 2007), Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (Steven Spielberg, 2008) and Edge of Darkness (Martin Campbell, 2010).

If not the Rocker Winstone, then acting accolades must go to the Mod ally Timothy Spall: the one-day shoot as Harry the projectionist in Quadrophenia led on, via a role as Paulus in The Bride to national fame as Barry in Roddam’s Auf Weidersehen, Pet and arthouse success in Mike Leigh’s films Life Is Sweet (1990), Secrets and Lies (1995), Topsy Turvy (1999) and All or Nothing (2002). Appearances in Stephen Poliakoff television plays such as Shooting the Past (1999) and Perfect Strangers (2001) and film work as varied as Still Crazy (Brian Gibson, 1998), Love’s Labour’s Lost (Kenneth Branagh, 1999), Enchanted (Kevin Lima, 2007) and a portrayal of Winston Churchill in The King’s Speech (Tom Hooper, 2010) – a role reprised atop Big Ben in the London 2012 Olympic Closing Ceremony – have led to the award of the Order of the British Empire. In landing the part of Peter Pettigrew / Wormtail he joined what has become known amongst Equity members as ‘the Harry Potter Pension Scheme’.

Phil Daniels worked again with Roddam as Bela in The Bride, as Danny, would-be manager to Hazel O’Connor’s aggressive punk singer Kate in Breaking Glass and as the eponymous Kid in Alan Clarke’s musical Billy The Kid and the Green Baize Vampire (1985). He worked with Les Blair as Terry the Boxer in Number One and as both of the Nunn Brothers in Bad Behaviour (1992); as another band manager, Neil Gaydon, in the spoof of ageing (Auf Wiedersehen) rock stars Timothy Spall and Jimmy Naill, Still Crazy; and voiced Fetcher the rat in Chicken Run (2000). Daniels has worked regularly on stage, notably as Alex in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Clockwork Orange 2004 (1990) while alongside his Blur video he has appeared frequently on television, from Gary Rickey in Holding On (1997), Terry Brook in Time Gentlemen, Please (2000–02), two years as Kevin in EastEnders (1985–), through to Ted Trotter in the Only Fools and Horses prequel, Rock and Chips (2010–11). Roddam’s Dylanesque message not to follow leaders was eventually given extra-diegetic momentum when the definitive Mod actor (heretically?) took on the role of strung-out biker Grouch in the British comedy Freebird (John Ivay, 2008).

Leslie Ash had brief, minor roles on film in Anwar Kawadri’s Curse of the Nutcracker (1982), Blake Edwards’ Curse of Pink Panther (1983) and Philip Saville’s Shadey (1985). She has worked mainly in television, firstly in an abortive role as presenter on Channel 4’s The Tube (1982–7), stabilising as a member of the all-female detective agency Cat’s Eyes (1985–87), before finding household fame as lust object Deborah in Men Behaving Badly (1992–98), nurse Karen Buckley in Where The Heart Is (2000–03) and a high-profile victim of trout-pout cosmetic surgery and a debilitating hospital infection. She returned to television in 2009–10 as scheming executive Vanessa Lyton in Holby City (1999–). Toyah Willcox, nominated for Best Newcomer at the Evening Standard Awards for her interpretation of Miranda in Jarman’s Tempest, was passed over in favour of Hazel O’Connor in Breaking Glass, though she later acted alongside Laurence Olivier as Anne in the television film of John Fowles’ The Ebony Tower (1984). With a distinctive pseudo-punk outfit and attitude, she found lisping pop stardom in 1981, charting regularly and gaining top ten successes with ‘I Want To Be Free’ and ‘Thunder In the Mountains’. In 1986 she married King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp, and found further success in the nineties on children’s television, first as the narrator of Brum (1992), then in the eponymous Toyah! (1997) and Toyah and Chase (1998), before peaking as voice artist and Ace Face of the sun for the BBC phenomenon Teletubbies (1997–2001).

Elsewhere, Trevor (now H.) Laird had roles as Beefy in the Stellman-scripted Babylon, as Floyd in Billy the Kid and the Green Baize Vampire and Hortense’s brother in Secrets and Lies. He worked again with Ray Winstone as Trevor in Love, Honour and Obey (Dominic Anciano, 2000) and twice with Doctor Who (as Frax, 1986 and as Clive Jones, 2007). Philip Davis (‘Phil’ from the mid-nineties) moved from humble beginnings as a roadie in Alan Parker’s Pink Floyd – The Wall (1982) to Kevin in Alien3 (David Fincher, 1993), Brian Bangs in Notes on a Scandal (Richard Eyre, 2006), before bringing an intertextual Mod element to the role of Spicer in Rowan Joffe’s mid-sixties transposition of Brighton Rock (2010). He has the kudos of being a Mike Leigh regular, from the bearded Cyril Bender in High Hopes (1988), through a cameo in Secrets and Lies to a BAFTA nomination as Stan in Vera Drake (2004) and the role of Jack in Another Year (2010). Television work has seen success as Maloney in Rose and Maloney (2002), Smallweed in Bleak House (2005), Brian in the mini-series Collision (2009) and hard-bitten DS Ray Miles in Whitechapel (2009–10). Davis moved behind the camera as director of I.D. (1995), a film that revisited Quadrophenia’s themes of youth tribalism and violence. Centred on soccer hooliganism, the film impressively focuses not on the hooligans but on the stages of brutalisation of a young undercover and Thatcherite policeman, Reece Dinsdale. Davis’ second direction, again well-reviewed, was Hold Back the Night (1999) where abused teenager Christine Tremarco flees home and befriends both a grungy environmental protester trying to stop a bypass through a forest and a terminally ill woman whose dying wish is to see the sunrise at Orkney’s Ring of Brodgar.

Garry Cooper had a string of minor roles in ‘cult’ successes, appearing as Tony in Channel 4’s opening P’tang Yang Kipperbang (Michael Apted, 1982), a squatter in My Beautiful Laundrette, (Stephen Frears, 1985), Davide in Jarman’s Caravaggio (1986) and Ronnie Pearce in Hettie MacDonald’s study of gay life, Beautiful Thing (1996). He worked regularly in television from the mid-nineties, earning tenure in 2004 as George Keating in Holby City. Mark Wingett was Tony in Breaking Glass and played alongside Elvis Payne’s Winston as Eddie in Barry Bliss’ study of two dole-survivors, Fords on Water (1984). That same year Wingett got his big break when cast as PC (latterly DC) Jim Carver in The Bill (1984–2010). Remaining with the series until 2005, his longevity was the premise for being the recipient of a Spring 2000 edition of This Is Your Life (1955–2007). Even uncredited actors moved on to renowned television careers, notably Mod John Altman as ‘Nasty’ Nick Cotton in EastEnders and Rocker Gary Holton as womaniser Wayne in Auf Wiedersehen, Pet.

The biggest success? After Sting this was arguably Gary Shail (Spider), who worked with Roddam and company on The Bride, and elsewhere featured as Oscar Drill in the Rocky Horror Picture Show follow-up Shock Treatment (Jim Sharman, 1981), as punky teenager Steve in Metal Mickey (1980–83) and as Guy in the cult television series of school leaver Johnny Jarvis (1985), for which he also composed the theme tune. Shail then left acting and followed the Mod dream to Motown where he wrote for Smokey Robinson. On his return to the UK Shail set up Natural Source Sound, and became the owner of the biggest sound studio for the country’s advertising industry – a true Mod profession. The other ‘dark horse’ contender is Jimmy’s 1962 Lambretta LI 150 series 3, registration number KRU 251. The Mod strategy of fetishisation as described by Hebdige, making ‘objects to be desired, fondled and valued in their own right’ (1979: 105), certainly bears out here: having remained in the Portsmouth area since filming closed, the fully restored model was sold at Bonham’s auction house in Knightsbridge on 25 November 2008. It surpassed its list price of £20,000 to £25,000, finally selling for £36,000. ‘Take it or leave it, my son. Take it or leave it.’

A boy, no girl and a bike.