CHAPTER ONE

George Mallory’s first climbing ground was the roof of his father’s church in the Cheshire village of Mobberley. An austere, thirteenth-century building, St. Wilfrid’s has a square stone tower that is visible, like a distant mountain crag, across the surrounding fields. For an imaginative boy of seven, who apparently knew no fear, there were many ways to reach the angled slate roof. A drainpipe led to a lower roof, which you traversed to the far end; climb another drainpipe, bracing your feet against the right-angled roof of an adjoining chapel; grasp the coping stone to heave yourself up, and you were there.

Mobberley, in the early 1890s, had other lures for George. “He climbed everything that it was at all possible to climb,” his sister Avie said. These included the walls dividing the farmers’ fields and the drainpipes of Hobcroft House, a rambling building half a mile from the church, where the Mallory family lived. Once George led his younger brother Trafford on to the roof and, while George knew how to get down, Trafford had to be rescued with a ladder. During a family seaside holiday at St. Bees in Cumberland when he was eight, he stood on a rock to see what would happen when he was cut off by the tide. The boatman who rescued him said that George had seemed quite unconcerned by the danger he was in.

It may seem incongruous that the elder son of the local rector should behave in so wayward a manner. Mobberley was a prosperous parish, with a number of mansions belonging to the merchants and industrialists of Manchester, a dozen miles away. Most of the villagers worked on the neighboring farms, or in the crepe mill by Mobberley Brook. Herbert Leigh Mallory was a devout and conventional man who frowned on radical or nonconformist views. He and his wife, Annie, were the epitome of respectability as they rode to St. Wilfrid’s through Mobberley’s stony lanes in their pony and trap. In his services he stressed the ritualistic and sacramental side of worship and communion, although he delivered more populist sermons after the local Methodists began attracting worshippers to their chapel near Mobberley Brook at the southern edge of the village. He was generous to the parish, helping to fund restoration work at St. Wilfrid’s soon after he became rector in 1885, and paying for new oak choir stalls.

Annie was different. Certainly she was well-meaning, doing her best to fulfill her role as the rector’s wife. During the services, she would occupy one of the front pews alongside her four children and make suggestions in a stage whisper to Herbert as he read out the church notices. She felt obliged to lead the singing but had more enthusiasm than a musical ear, for she was often several bars ahead of the rest of the congregation and would swoop down on her notes from higher up the scale. Similar disharmony marked her life at Hobcroft House. She was chaotic and disorganized, moving perpetually from crisis to crisis. She found it impossible to keep servants as she changed her mind frequently and exasperated them by ringing all the bells simultaneously to bring them scurrying from all parts of the house. She was a hypochondriac who was constantly anxious about her health and took herself off for cures at spas—Bath in southwest England and Aix-les-Bains in France were her favorites. Today she would be called a drama queen.

As a mother, her children observed, she was more noticed for her absences than the attention she gave them. As a result, Avie remarked, “We were exceptionally unruly children.” The children were closer to each other than to Annie, although George’s two sisters, Avie and Mary, vied for his affections. They came to resent their mother’s interference and when she did intervene she usually provoked another dispute. “Why is it,” George once asked, “that whenever mother comes in a row starts?” There were rows when she wanted them to learn the piano, and on one occasion Mary slammed down the piano lid and marched out. Herbert’s habit, when he heard storms such as this brewing up, was to quietly withdraw.

Annie’s most positive effect as a mother was to encourage her children to acquire a spirit of adventure. Sometimes she led them on walks through the fields, ignoring the farmers and other landowners whose walls they climbed. It was thus not surprising that George should acquire a taste for risk. “It was always fun doing things with him,” Avie said. “He had the knack of making things exciting and often rather dangerous.” She learned never to suggest that there might be anything that was impossible to climb, as that only spurred him on. Once he talked of lying between the railway tracks and letting a train pass over him. “I kept very quiet,” Avie said. “I was afraid he would do it.”

As the engraved marble plaques and gold-inscribed wooden panels at St. Wilfrid’s testify, there have been Mallorys at Mobberley for centuries. The first is Thomas Mallory, appointed rector in 1621. There is a second Thomas Mallory in 1684, a third in 1770. The year 1795 brings a John Holdsworth Mallory, whose occupancy is commemorated with an intriguing verse from the book of Matthew: “When thou does thine alms, let not thy left hand know what thy right hand doeth.” In 1832 this Mallory was succeeded by George Mallory, the father of Herbert Leigh Mallory. Finally there was Herbert Leigh Mallory himself in 1885.

Although Herbert was the last of the Mallorys to be Mobberley’s rector, there is another memorial to the Mallory family. In a wall on the left-hand side of the church, close to the pulpit, is a stained-glass triptych depicting three heroic figures from English mythology, King Arthur, Saint George, and Sir Galahad. It commemorates Herbert Mallory and his two sons, Trafford and George. Trafford became head of the Royal Air Force’s Fighter Command and died in a plane crash in 1944. There is an inscription to George that reads: “All his life he sought after whatsoever things are pure and high and eternal.” At last in the flower of his perfect manhood he was lost to human sight between earth and heaven on the topmost peak of Mount Everest.” The window is most moving when the light from outside bathes the flagstones of the floor with patterns of red and blue.

There is one curiosity about the memorial, for the name of George Mallory is shown as George Herbert Leigh Leigh-Mallory. How George Mallory came to acquire such a convoluted name is part of a family history that is not quite as straightforward as the roster of names at St. Wilfrid’s appears to suggest. The story is one of interlopers, disputed wills, premature deaths, and a concern for status and appearances, which left its mark on the memorial to George Mallory himself.

Thomas Mallory, the first of the Mobberley Mallorys, was a seventeenthcentury carpetbagger. He was already the Dean of Chester when he came to Mobberley in 1619 and purchased the living of St. Wilfrid’s church. A year or so later he bought the nearby Manor House, which made him the squire of Mobberley. He had the right to appoint the village rector and so he chose himself.

GEORGE MALLORY’S 19TH-CENTURY FOREBEAR

PARENTS, MARRIAGE AND CHILDREN

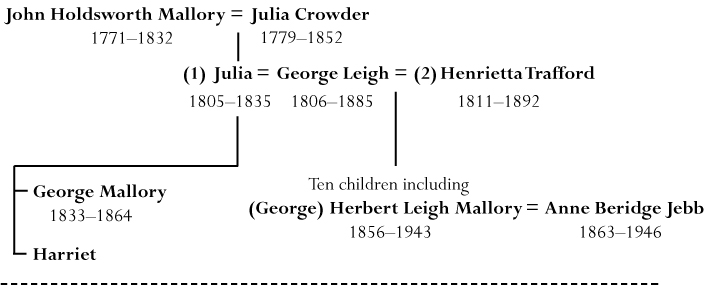

The first tree shows the two marriages of George Leigh, George Mallory’s grandfather. When Leigh married Julia Mallory, he took the Mallory name. When he married for a second time, he restored “Leigh” to his surname (see pages 23 and 26).

His descendants inherited the same rights and sometimes appointed outsiders as rectors, sometimes themselves, as the names recorded at St. Wilfrid’s shows. However, the George Mallory—father of Herbert Mallory, grandfather of George Mallory the mountaineer—who became rector in 1832, was not a Mallory at all, but an interloper. His real name was George Leigh, a curate from Liverpool. In 1831 he came to Mobberley and asked the incumbent rector, John Holdsworth Mallory, for permission to marry his daughter, Julia. John Holdsworth Mallory had no sons, and no better prospect for a husband for his daughter either. He was also seriously ill. He agreed to Leigh’s request on one condition. When Leigh married Julia he should forsake his own surname and take hers, thus ensuring the survival of the Mallory name and line.

The couple were married at St. Wilfrid’s in 1832, becoming George and Julia Mallory. Julia’s father, John Holdsworth Mallory, died three months later. George and Julia had two children: a son, also called George Mallory, and a daughter, Harriet. Julia died in March 1835, when she was just twenty-nine. Barely a year or so after that the widowed George Mallory married again. His new wife was a cousin, Henrietta Trafford from Outrington in Cheshire, and they had ten children. Now that he was free of the oversight of his first wife and her father, George Mallory reinstated his old name. He did so by adding Leigh to his own and his children’s names, giving the impression that it formed part of their surnames. When his seventh son and tenth child was born in 1856, he was christened Herbert Leigh Mallory.

George Leigh Mallory also managed to acquire the Mallory family estate. John Holdsworth Mallory had bequeathed the Manor House and some nearby cottages to his grandson, Julia’s son George, hoping to ensure that it remained within the Mallory family. But when grandson George became an adult he incurred debts that he could only discharge by selling the Manor House and the nearby cottages. They were purchased by his father, George Leigh Mallory, who thus completed his takeover of both the family name and its estate.

Of the original George Mallory’s seven sons, it was Herbert who was selected to follow his father into the church. He was sent to boarding school at King William’s College on the Isle of Man, progressing from there to Trinity College, Cambridge. He left with a B.A. in 1878 and began his ecclesiastical apprenticeship in a succession of junior posts: assistant curate at St. Andrew the Less in Cambridge; curate “in sole charge” of the Abbey Church, Cambridge. It was during this time that he met the young Annie Jebb.

The Jebbs were a prosperous church family from Derbyshire. Annie’s father was the Rev. John Beridge Jebb, named after a relative, the great eighteenthcentury evangelist John Berridge (it should be noted that alternative spellings of the name, Berridge and Beridge, appear in family records). John Jebb owned a splendid mansion, Walton Lodge, with forty-one acres of grounds, and was minister at the nearby church of St. Thomas. Like Herbert Mallory’s father George, he too married twice. His first wife, Charlotte, came from Devonshire, and they had a son, John Beridge Gladwyn Jebb, who became an adventurer in the finest Victorian tradition. But Charlotte died in 1859 and in 1861 John Jebb married Mary Frances Jenkinson, a vicar’s daughter from Kensington. Mary became pregnant but John Jebb died shortly before she gave birth to their first daughter, Anne Beridge, who was born on April 16, 1863.

Mary Jebb was thus left to bring up Annie alone. She found ample consolation in her husband’s will. John Jebb had left his son by his first marriage a meager inheritance consisting of his gold watch and the furniture that had belonged to his first wife. Everything else went to Mary and her daughter. Mary acquired railway company shares worth £6000 ($46,000)*, while Walton Lodge and its forty-one acres were left in trust to her daughter Annie. The family of John’s first wife were outraged and wanted to challenge the will, but there was nothing they could do, and Mary and her daughter Annie continued to live at Walton Lodge. There Annie, as she was known, had an unfettered upbringing. Her mother was preoccupied for much of her life with good works, setting up a canteen for the mill girls of Derby, running a scripture class for local policemen, opening a hospital, and becoming its matron. During her mother’s absences, Annie was taught by governesses and was often lodged with her mother’s friends. She acquired a taste for the freedom of the countryside, riding out on to the moors on her pony, walking and scrambling in the hills when she was taken on holiday to Wales.

Meanwhile her mother, anxious to have her daughter safely married, resolved to find her a husband at an early age. According to family legend, she effectively brought about a shotgun wedding. Annie met Herbert Mallory when she was still a teenager and he was completing his theological studies. When Herbert showed a tentative interest in Annie, her mother accused him of trifling with her daughter’s affections and demanded that he marry her. Herbert’s family was incensed, telling him that the accusation was preposterous. But Mary persisted in her accusation and Herbert, who said he did not want to hurt Annie’s feelings, complied. He was twenty-five, she was nineteen, when they were married in Kensington in June 1882. They spent their honeymoon in the Lake District, eating copiously and working off the excess through hill walking.

By then Herbert was a curate at the Abbey Church in Cambridge. He next moved to the parish of Harborough Magna near Rugby, then became assistant curate at Great Haseley in Oxford. In 1884 he moved back to Mobberley. His elderly father was ill, and the moment when Herbert would succeed him was nearing. Annie was pregnant, and so rather than move into the Manor House, where his parents lived with two of his unmarried sisters, Herbert looked for somewhere else to live. A mile or so from St. Wilfrid’s he found a grand Elizabethan house called Newton Hall, which he rented from a prosperous Birkenhead publican named Thomas Adkinson. With its white-painted facade and three steep gables, it seemed an appropriate home for the prospective rector of Mobberley and his wife.

On February 3, 1885, Annie gave birth to their first child, Mary. Just four days later, and in preparation for the family succession, Herbert became the curate of Mobberley. His father, George Leigh Mallory, died on July 26, and on September 23 Herbert became the rector of Mobberley. In theory he should have moved back to the Manor House, which was still occupied by his mother and two sisters, but on March 18, 1886, the church authorities in Chester gave him and Annie permission to remain at Newton Hall. It was there on June 18 that their second child and first son was born. His father—a “Clerk in Holy Orders”—registered the birth, recording his name as George Herbert Leigh Mallory. He was baptized at St. Wilfrid’s seven weeks later.

Herbert and Annie had a third child, Annie Victoria—known throughout her life as Avie—at Newton Hall on November 19, 1887. By now the Mallorys were planning a home of their own, and in 1890 construction of Hobcroft House began in Hobcroft Lane on the far side of St. Wilfrid’s from Newton Hall. The family left Newton Hall and moved into Hobcroft House around the end of 1891. Annie’s mother Mary joined them soon afterwards, living with them until her death in 1906. The Mallorys’ fourth and last child, Trafford Leigh Mallory, was born at Hobcroft House on July 11, 1892.

The family lived in Hobcroft House until 1904, and it is from these twelve years that their children’s principal memories of life in Mobberley emanated. These accounts were passed down to their children, who amplified them with their own recollections of Herbert and Annie. They remembered how Herbert called the servants to attend when he said grace before meals, and how he would read aloud from the bible when the family was seated around the dining table. They also recalled how Herbert acquired a diplomatic deafness as his strategy for coping with Annie’s excesses and then, after they had left Mobberley, would retreat to his study with the family chauffeur and wait there until the latest crisis had passed.

Strongest of all were the memories of Herbert’s and Annie’s extravagance. Although photographs show that Annie had a reasonably trim figure, she was a compulsive eater who observed a succession of mealtimes: breakfast, the mid-morning snack known as elevenses, lunch, a mid-afternoon snack, high tea, dinner, and supper. There was always far more food provided than anyone could consume, from the mammoth breakfasts when the sideboard was weighed down with eggs, ham, bacon, kippers, and kedgeree, to the enormous joints of beef or mutton that were served for dinner and remained half-eaten in the larder for days. The Mallorys bought every new household gadget on offer, from carpet-sweepers to ice cream–makers. They had a cavalier attitude towards their debts, and children or grandchildren who went to visit them would search the house for bills from local tradesmen that were long overdue and had to be paid.

Such profligacy may help to explain one of the family mysteries. The Mallorys should have been more than comfortably off. Soon after moving into Hobcroft House, Herbert had acquired the Manor House, left to him when his mother died. Annie should also have benefited from the inheritance settled on her by her grandfather. Yet by the time Herbert and Annie died in the 1940s, the family fortune had gone. “They were as poor as church mice,” their grandson John Mallory observed.

All of this left its mark on the young George. He too had an inconsistent attitude towards money, sometimes parsimonious, sometimes extravagant. Money became an issue in his marriage and was a constant irritant in his dealings with the Mount Everest Committee. He worked hard to improve his practical skills but never overcame his endemic forgetfulness, to the delight and despair of his friends. But his upbringing also helped frame his character as adventurer, experimenter, risk-taker; someone who delighted in new experiences, determined to push them to the limits.

But what of the name, George Herbert Leigh Leigh-Mallory, which is recorded on the memorial at St. Wilfrid’s? One of the Leighs resulted from the determination of his grandfather, George Leigh, to restore his own surname. The second stemmed from his father’s concern for propriety and status. In 1914 Herbert Leigh Mallory decided to apply for a family coat of arms. But when the officials at the College of Arms delved into his family history, they found a curious anomaly. It appeared that when George Leigh assumed the name Mallory in 1832, the change applied only to his first marriage, and not to his second. This news was broken to a shocked Herbert Leigh Mallory in March 1914 by the Garter King of Arms, Sir Arthur Gatty, who told him that as a consequence he was “in the almost unique position” of having no surname at all.

All of this was related by Herbert in a letter to his son George on March 30, 1914. Herbert asked his son not to tell anyone else: “It seems so silly,” he confessed. But there was good news too, for Sir Arthur had found a solution. The best way out of the impasse, he suggested, would be for Herbert to apply for a new surname, Leigh-Mallory. Herbert agreed that this was the most convenient solution, particularly as he had been signing himself “Leigh Mallory” anyway. So it was that the boy who had been christened George Herbert Leigh Mallory officially became George Herbert Leigh Leigh-Mallory. George never used his full name, although he once wrote to the Mount Everest Committee to insist that his rightful name was George Leigh Mallory. But his father’s social aspirations went unsatisfied as his request for a coat of arms was turned down.

When George was nine, he was sent away from home. After a brief spell at a preparatory school at West Kirby, near Birkenhead, which was abruptly closed down when its headmaster died, he moved to Glengorse, a preparatory school in Eastbourne. It had fifty-four pupils and George shared a dormitory with five other boys. “My dear Mater,” he wrote to his mother on February 14, 1896, “I had my first experience of football on Friday. It was a very nice experience. The first damage I did was to charge two boys over on their faces, the second was to kick the ball into a boy’s nose, and the third damage was to charge a boy over on his ribs.”

Much later, George was to challenge the practice of separating children from their parents by dispatching them to boarding school, particularly at so young an age. He felt that it produced people who were “superficial and self-satisfied” and “disastrously ill-equipped for making the best of life.” It was a remarkable indictment, stemming from his experiences as both pupil and teacher. But at Glengorse he showed nothing but enthusiasm for his new life, even if his spelling required attention. “There is only one boy in the school who is atal nasty,” he told his mother, adding that this recalcitrant pupil was the matron’s son. His biggest shock came when one of his friends decided to run away from Glengorse. Although George had no wish to leave Glengorse he agreed to keep him company, and brought along his geometry books wrapped in a brown paper parcel. The two runaways were tracked down by a teacher who promised that if they returned to Glengorse at once they would not be punished. George agreed but as soon as they had arrived they were soundly beaten. When George told the story in later life, he made clear his outrage that the teacher should have tricked him into going back by telling a lie.

George’s strongest school subject was math, and in 1900, when he was thirteen, he entered for a math scholarship to Winchester College. Winchester had a high academic reputation among the English public schools and George faced stiff competition. He won the scholarship, saving his father all but £30 ($144.00) of the customary annual fees of around £200 ($960.00). When he started at Winchester in September he was placed in College House, the preserve of the brightest pupils, and allocated rooms in the main quadrangle, known as Chamber Court. There he was given one of the studies, known as the toys, in a communal living room, or chamber, and slept in a dormitory on an upper floor with up to ten other boys.

Even more than at Glengorse, George immersed himself in the spirit of the place. He rapidly adopted its private argot (known as the “notions”) and within days of arriving wrote to his mother. “I like being here very much—ever so much better than Glengorse, and I like the men better too. (Instead of chaps, we always say men): We have plenty of work to do, and I’m afraid I’m running you up a heavy book bill; we shan’t begin playing footer—the Winchester game—for some time yet; we get up at 6.15 and begin work—morning lines it’s called—at 7.00.” A month later he told her he was enjoying Winchester immensely. “It’s simply lovely being here; life is like a dream.”

One of the characteristics that marked out George from his contemporaries, both at Winchester and later at Cambridge, was his versatility. Many of the scholarship boys concentrated on their academic studies, but George excelled at sports too. He took up Winchester’s idiosyncratic version of soccer, which took place on a long, fenced-off pitch with anything from six to fifteen a side, and played in the technically demanding “kick” position in the college team. He became the best gymnast in the school, the only one who could perform a complete circle with his arms and body held straight on a horizontal bar. In 1904 he was a member of the eight-strong shooting team that competed for the Ashburton Shield against the other public schools at the annual Bisley contest. The team won with a bull’s eye on its very last shot and George relished every moment of the triumph. “It was simply glorious,” he wrote to Avie. “We won the Public School Racquets last holidays, we badly beat Eton at cricket, and now we have won the Public Schools Shooting, which is really the best of the lot, because every decent school goes in for it, and it comes into public notice much more than anything else.” The entire school turned out to greet the team at Winchester station, cheering them and carrying them shoulder-high into college. “It is simply ripping,” George said.

While George’s account of the contest showed that, in sport at least, he was absorbing the public school ethos, he also challenged some of its excesses. At the end of the autumn term (“Short Half ”) in 1903, his chamber prefect—an older boy who supervised his chamber—recorded notes of George’s progress. George was “a mathematical-minded, smooth-chinned, pre-Raphaelite looking young man” and had insisted on complaining about a prefect in another chamber who was notorious for his bullying. By the following term (“Common Time”) the problem seemed to have been dealt with, and he was described as a “kindly individual character” and a “sweet young fellow.”

George was now at a critical point in his school career. He had been studying math and chemistry, subjects that would equip him for the army, and he was entered for exams that would qualify him for the officer training school at Woolwich. George had no wish to become a soldier and told his sister Mary that he hoped to fail. As a letter to his mother suggests, he duly ensured that he did. “The mathematical papers were so absurdly easy that it was quite impossible to score on them, especially as I always do easy papers badly,” he told her. Besides, leaving Winchester would have been “perfectly awful.”

Certainly George was enjoying life at Winchester, and he was about to explore a new activity, which would bring even greater pleasure and rewards. He did so through the intervention of the senior master (“College Tutor”) in his house, Graham Irving, a member of the Alpine Club and later a prolific writer about mountaineering. As Irving told it, he was looking for new climbing companions after his own partner had keen killed in an accident. He discovered that one of his pupils, Harry Gibson, a keen photographer, had been on several trips to the Alps with his father. From Gibson, he learned about George, and his habit of climbing on buildings.

Later, when writing his obituary for the Alpine Journal, Irving recalled his first impressions of George. “He had a strikingly beautiful face. Its shape, its delicately cut features, especially the rather large, heavily lashed, thoughtful eyes, were extraordinarily suggestive of a Botticelli Madonna, even when he had ceased to be a boy—though any suspicion of effeminacy was completely banished by obvious proofs of physical energy and strength.” It was an early example of the impact George could have on those meeting him and of the important relationships this could lead to. At that time, George had done no serious mountaineering at all. Although his forays on drainpipes and roofs had continued at Winchester, he had shown little curiosity about the wider mountaineering world, and had read none of the mountaineering books in the college library. Irving—who at twenty-seven was just ten years older than George—nonetheless proposed that he and Gibson should go to the Alps with him that summer. Both were delighted at the prospect, and their parents gave their consent.

The three took the night ferry from Southampton to le Havre on August 2, reaching Bourg St. Pierre in the French Alps on August 4. Over the next three weeks Irving provided a dramatic introduction to alpine climbing, with all its hazards and rewards. The days were long and demanding, often lasting from dawn to dusk or beyond, as they tramped over glaciers, crossed high mountain passes, and tackled several major peaks, including Mont Blanc, highest mountain in the Alps. They had to contend with altitude sickness, rockfall, storms, and bitter cold. George devoured it all, writing long, detailed letters to his mother and contributing to a diary of the trip, describing the overnight stops in primitive mountain huts, the rudimentary food, and the characters they met, like the hut guardian who had climbed with the great Italian mountaineer and photographer, Vittorio Sella.

Their first climb, on a snow peak named Mont Velan, brought a spectacular view of sunrise on Mont Blanc. “The first few hundred feet of the climb were in moonlight, and the dawn afterwards was glorious,” George wrote. Then the sun rose on Mont Blanc, “which was a perfectly delightful pink; and we watched it spread over a range of peaks with infinite delight.” Sadly, the attempt ended in failure when both George and Gibson were hit by altitude sickness. George vomited a dozen times and they turned back 600 feet from the summit. Their next attempt was on the Grand Combin, a complex mountain peak with a long approach: they climbed the 1800-foot west ridge and then started across a vast snowfield leading to the summit. After “a rest and some grub,” George wrote, “[we] went up the last 700 feet in fine form in half an hour. The Grand Combin is 14,100 feet and of course the view from the top was simply ripping.” Irving later wrote of “the blessed certainty in all of us that we had spent the best day of our lives.”

While Gibson had to go home after a week, George and Irving spent seventeen of the next eighteen days on the move, traversing peaks and cols as they crossed between France, Switzerland, and Italy. There were several troubling moments: while descending from the Col de l’Evêque, Irving fell into a hidden crevasse, George helping to haul him out on their rope; later they lost their way and lost two hours crossing the wrong col. Most dangerously of all, they were assailed by rockfall as they were returning to France via the Col du Chardonnet. George dived for shelter but Irving was almost hit by a boulder. “The cannonade probably continued for about half a minute and seemed, both from the noise, which occurred in three main waves, and from the debris, to be fairly extensive,” George related. “Altogether it was a very interesting and somewhat exciting incident.” There was bad weather during their final week, and they were driven back by a storm as they attempted Mont Blanc via the Dôme Glacier and the Bionnassay Arête. After sheltering in the Dome hut overnight they tried again the next day, climbing the final stretch in a bitter wind that pierced their clothing and threatened to tear them from their holds. Having come through such a severe test, Irving wrote, they had a “thrill in their hearts … It is impossible to make any who have never experienced it realise what that thrill means. It proceeds partly from a legitimate joy and pride in life.”

While George found the gamut of mountain experiences utterly exhilarating, Irving’s actions were to lead him into a bitter controversy. Even the most experienced alpinists were unsure whether it was safe to climb without professional guides; and yet Irving continued to take boys from Winchester, most of them novices, to the Alps for the next four years. In December 1908 he read a paper to the Alpine Club entitled “Five Years with Recruits.” He described how he had enlisted George and Gibson and justified the practice as “fitting the recruits for service in the great and growing army of mountaineers.” It was a somewhat truculent defense for, after admitting that he had expected to be attacked for “corrupting youth,” he accused his critics of taking more risks during their climbing careers than he had, adding that he would not have wanted to climb with some of them himself. It was a provocative onslaught on some of the most distinguished names in British alpinism, among them Tom Longstaff, Walter Haskett Smith, Douglas Freshfield, and Geoffrey Winthrop Young, who sent a collective letter to the Alpine Journal to dissociate themselves from Irving’s beliefs. Willfully or otherwise, Irving was missing the point, as there was a world of difference between taking chances for oneself and putting other people, particularly young people, at risk. Irving could claim, as he did, that he had got away with it, but the odds eventually turned against him, for in 1930 he was leading a party of young climbers on l’Evêque at Arolla when two of them slipped and fell to their deaths.

Four days after reaching Chamonix, George was back in Britain. Home was no longer Mobberley, however. During his absence the family had been preparing to leave rural Cheshire for a far less attractive neighborhood: an industrial parish adjoining the docklands on the Mersey at Birkenhead. Instead of trees and fields, there would be rows of terraced houses clustered around the church of St. John, a mid-Victorian building with a tall spire set among the homes of Birkenhead’s dockyard workers. The precise reasons for the move have remained a mystery; but several explanations have circulated both in the family and in Mobberley, together with some convenient glosses that almost certainly concealed the truth.

The parish register for Mobberley in the summer of 1904 gives little away. It reveals only that Herbert proceeded with his parochial business, helping to organize the usual summer fruit, flower, and vegetable show. Then came reports that he had decided to leave Mobberley, the villagers presenting him with an illuminated vellum address and some items of furniture—a dressing case and bookcase—to mark his departure.

Other documents contain some clues. The records of the Chester diocese reveal the details of a suspiciously neat transaction involving the Rev. Herbert Leigh Mallory, rector of the parish church of Mobberley, and the Rev. Gerald Campbell Dicker of the vicarage and benefice of St. John, Birkenhead. On the same day, July 27, 1904, both men tendered their resignations to the Bishop of Chester. They were then installed in each other’s former parish, Herbert Mallory taking over at St. John’s, Birkenhead, Dicker replacing him at St. Wilfrid’s in Mobberley. The switch, so smooth and convenient, looked, in short, like an ecclesiastical fix.

Since then, several possible explanations have emerged. One version, apparently retailed by the Mallorys’ daughter Mary and passed on to her daughter Barbara, asserted that her mother Annie had become excessively friendly with a local man, although how far this excess of friendship went remained unclear. A second version, which reached some of Avie’s descendants, related that it was not Annie but Mary herself who had implicated her family in scandal. There was a third version that placed Herbert at the center of the episode. Herbert, who had business connections in Liverpool and Birkenhead, had incurred a debt with the Rev. Gerald Dicker, which was settled when he exchanged his Mobberley parish for the bleaker environs of Birkenhead.

Then there was version four, which also featured Herbert: it was neither his wife nor his daughter who became entangled with a parishioner, but Herbert himself. This version, which was still being recounted by older Mobberley residents ninety years later, held that Herbert had been “involved” with several other parishioners, namely the young serving women who came and went from the Mallory household so frequently. The story goes that when Annie learned about Herbert’s transgressions she at first refused to go to Birkenhead with him, only changing her mind when she realized that this would create an even greater public scandal.

The evidence to decide which of these accounts could be true is scanty. But there is one further clue. In the spring of 1904 there was an air of crisis in the Mallory family, for Annie had suffered a nervous breakdown. Avie accompanied her to Boscombe, a town near Bournemouth on the south coast, where she was to convalesce. George visited her there and took her on a tour of Winchester. The timing is suggestive, for other evidence shows that Herbert was preparing his family for the move to Birkenhead at about this time, and long ahead of the maneuvers in the bishop’s office in Chester. On May 18 George wrote to Avie from Winchester to inform her he had received a letter from their father telling him “a lot more about Birkenhead.” His father had told him it was “an exceedingly important parish, so that father is jolly lucky to get the chance of it, and I think he is quite right in accepting.” Herbert appeared to be anticipating doubts about the move: while admitting it would be a “wrench” to leave Mobberley, “he seems to think that it won’t be at all a bad place to live.” George remained puzzled, particularly when he learned that church politics were involved. In a letter to his mother on August 23, in which he supposed she was “fearfully busy getting things ready to move,” he added the intriguing remark: “I can’t understand the connection of Archdeacon Barber.”

From this fragmentary evidence, it is clear that none of the Mallorys’ children was told the whole truth. Our best guess—and it remains a guess—is that some kind of impropriety, possibly sexual, was overlain by some equally murky church politics. We could find nothing in the diocesan records held in Chester to enable it to be resolved, and it remains a tantalizing episode in the backplot of the Mallory family history.

The Mallorys’ new home was St. John’s Parsonage, a somber mid-Victorian building with a large garden in Slatey Road on the edge of industrial Birkenhead, half a mile from the church. Herbert pursued his new duties with his customary commitment, moving a vote of thanks at the next church meeting to the lady parishioners who had decorated the church so magnificently at Easter. Annie engaged a new raft of servants, whose terms in office proved to be shorter, if anything, than those of their counterparts in Mobberley.

George, now seventeen, returned to Winchester in September for the start of his final year. In a bold move, he decided that he wanted to study a subject that concerned the real world, and switched from math to history. Irving was impressed with his progress and recommended that he sit for a history scholarship to Cambridge. His father had been at Trinity College but Irving suggested he try for Magdalene, a smaller and more intimate place. When George sat the exams he was awarded a scholarship known as a sizarship, an achievement all the more notable since he had taken up his new subject at such a late stage.

As the summer approached, so did a second visit to the Alps. Climbing had gripped George’s imagination, and he had been practicing his techniques on the Winchester architecture, attracting a rapt crowd when he bridged his way up between a chimney and the brickwork of a gate tower fifty feet above Chamber Court. Irving meanwhile had been on the lookout for more recruits. In January he formed the Winchester Ice Club—he was the president—and held its inaugural meet in Snowdonia in January, staying at the Pen y Gwryd Hotel. George could not be there but Harry Gibson attended, plus two of the new recruits, Harry Tyndale and Guy Bullock—the same Bullock who was George’s companion when he obtained his first visionary sighting of Everest in 1921.

The Ice Club returned to the Alps in August 1905, with Tyndale and Bullock—but not Gibson—joining Irving and George. It was more of a sociable affair than the previous year, for Irving had invited his sister as well as Tyndale’s mother and his two sisters. The climbing proceeded at a relatively easy pace, concentrating on the straightforward peaks around the Val d’Arolla high in the Pennine Alps above Sion in Switzerland, with glistening sunrises, glowing sunsets, views of the peaks under fresh snow, and hearty evening meals in mountain inns. While it was a far less strenuous trip than in 1904, it helped George consolidate his skills, learn about safeguarding less experienced climbers, and appreciate just what he had achieved the previous year. He also became acquainted with the frustrations of sitting out bad weather, for there were several blank days due to storms.

On August 21, Irving, George, and Bullock left the novices behind to attempt the Dent Blanche, a fang-like 14,000-foot peak at the heart of the Pennine Alps. It had a daunting reputation, as the Welsh pioneer Owen Glynne Jones had fallen to his death from its west ridge in 1899, but Irving was undeterred. They left the Bertol hut at 3:15 A.M., crossing a huge snowfield by moonlight, “on the most delightful hard crisp snow,” George wrote, then as dawn broke, embarked on a scramble over easy rocks which took them on to the long, exposed south ridge—a serious alpine undertaking even today. As they climbed, George related, “peak after peak was touched with the pink glow of the first sun, which slowly spread until the whole top was a flaming fire—and that against a sky with varied tints of leaden blue.” They reached the summit before midday, and duly celebrated, for as George told his mother, the Dent Blanche was “the one peak we had set our hearts upon doing.”

The rest of the stay was blighted by bad weather, but George was content. He left the Alps on the last day of August, returning to Birkenhead on September 2. In less than a month he would be starting at Cambridge: another new world to enjoy and explore.

*All U.K. Sterling figures have been converted to U.S. dollars at the rate prevailing at the time. In 1863, £1 was $7.67.