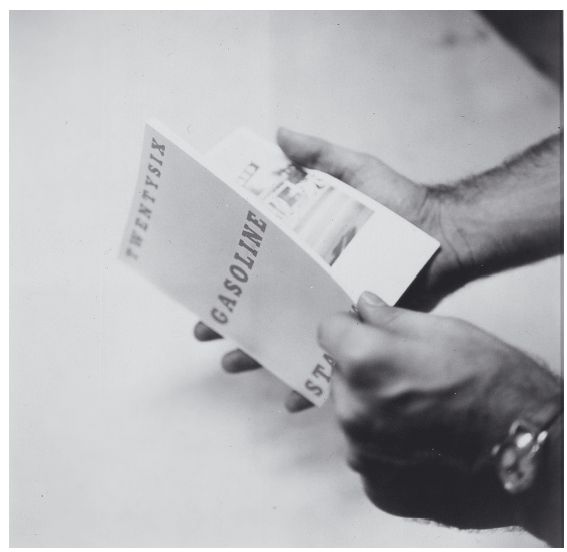

1 Ed Ruscha, Hands Flipping Pages (Twentysix Gasoline Stations), 1963. Gelatin silver print, 25.1 × 25.1 cm. Photo: © Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

2

AUTO-MATICITY: RUSCHA AND PERFORMATIVE PHOTOGRAPHY

Ed Ruscha’s books are puzzling. While his paintings find a plausible interpretative context in the work of Jasper Johns and Pop Art, his books are more often viewed as proto-photo-conceptual. Ruscha’s response to these attempts at categorization has been to distance himself from both pop and conceptual art, but he has always acknowledged the importance of the work of Marcel Duchamp, especially in relation to the books. He has in fact declared that ‘the spirit of Duchamp’s work is stronger in my books than in anything else’.1 He knew Duchamp’s work in reproduction from his high school days, and in 1963 he was able to see the work and meet the man in person at the first major Duchamp retrospective held at the Pasadena Art Museum.2 It is his reception of Duchamp that makes Ruscha’s work proto-conceptual. But exactly which Duchamp was important for him? Certainly not the ‘appropriationist’ Duchamp that resurfaced in a certain strand of critical conceptual art and later issued in the work of Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine or Richard Prince; or the Duchamp as founder of institutional critique, carried forward by artists such as Daniel Buren or Hans Haacke. Ruscha’s hard-edged style of painting may look back to Duchamp’s intense precision-painting in, for example, the Chocolate Grinder (No.1) of 1913, but the books seem related to the reception of another Duchamp in the United States which might be called the instructional and performative Duchamp. This is the legacy most avidly developed by the experimental composer, John Cage, and the group of artists influenced by him who in 1962 were to become Fluxus. Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Morris are often cited as the most important inheritors of this tradition, but, I will argue, Ruscha should be added to this list.

Ruscha’s books are frequently, and rightly, described as ‘cool’, yet the artist declared, in an interview of 1989, that they were ‘hot – almost too hot to handle’ and, also, ‘powerful statements, maybe the most powerful things I’ve done’.3 They were as cool in conception and as hotly subversive as Duchamp’s readymades. Yet rather than following the logic of the readymade, they put into operation another strategy inaugurated by Duchamp’s 3 Standard Stoppages (1913–14). Ruscha once remarked that Duchamp had exhausted or ‘killed’ the idea of displaying an ordinary object as art, so the books staked out a different, although related, strategy – one that was arguably more radical since they were circulated without the support of the framing gallery system.4

A recent book about the pre-history of conceptual art by Liz Kotz, Words to be Looked At: Language in 1960s Art (2007), is very helpful in making the link between conceptual art and earlier performance-based pieces which were governed by a notational system or ‘score’. Particularly helpful in this context is the chapter called ‘Language between Performance and Photography’, where Kotz argues that the stress that conceptual artists put on language had its roots in a practice in which a verbal score or set of instructions was performed. When this strategy is annexed to photography, she writes, ‘such notational systems dislocate photography from the reproductive logic of original and copy to reposition it as a recording mechanism for specific realizations of general schemata’. Kotz is concerned to point out how this brings the execution of a work closer to an utterance in language: ‘The work of art has been re-configured as a specific realization of a general proposition.’5 What she means by this is that the score or instruction governs the individual utterance or performance. The analogy Kotz makes here between the pair of terms ‘instruction or score and performance’ and ‘linguistic system and individual utterance’ is imprecise, but at least it serves the purpose of relating this type of work to the legacy of structural linguistics and its critique of authorship. However, Kotz’s linguistic emphasis does not adequately bring out the open-ended, experimental character of the work. In my view, the brilliance, for instance, of Lawrence Weiner’s Statements published as a little volume 1968, one of which reads, ‘A 36” × 36” removal to the lathing or support wall of plaster or wall board from a wall’, is the unpredictable pattern of struts, pipes and wires that are exposed when the minimal instruction is performed – although, admittedly, this rather goes against the grain of his own Statement of Intent (1969): ‘The piece need not be built.’ This example demonstrates clearly the combination of terse verbal instruction, performance, and openness to chance that characterizes much of the work of this period. The way the instruction is often instantiated with a simple square removal of plasterboard also puts the work in touch with the sort of photography that simply frames something that might otherwise go unobserved.

Of course, Ruscha’s early books pre-date the Statements by several years, so a context for understanding their invention has to be sought earlier. Apart from Duchamp’s famous ‘instructional piece’, about which more later, work that might have formed the background to Ruscha’s highly original books is that done by a group of artists influenced by John Cage and later associated with Fluxus. The minimal verbal instructions or ‘event scores’ for performance pieces by George Brecht, for example, were presented on cards in precise graphic form. The Fluxus composer, Lamonte Young, whose Composition 1960 #10 was dedicated to Robert Morris, consists of the instruction, ‘Draw a straight line and follow it’. The instruction is simple yet open to any number of realizations. In 1961, Morris and Young collaborated on a performance of this piece in which they laboriously traced and retraced a line on stage twenty-nine times. Kotz notes that such pieces have the effect of bringing something to our attention by framing or pointing to it, especially things that are in danger of disappearing ‘back into the quotidian’.6 In this respect, they resemble readymades which had a habit of disappearing. Despite suggestive similarities, the relative obscurity of this proto-Fluxus activity in the early 1960s suggests that we should treat it as an illuminating parallel development rather than as an actual precedent for Ruscha’s books.7

The way that the Fluxus ‘event scores’ and performances frame or point to something in the world throws light on Ruscha’s ‘performative’ use of photography in his books. Performative photography begins with an instruction or rule which is followed through with a performance. The use of the term ‘performative’ in this context is meant to invoke the difference between performance and performativity. Making use of Jacques Derrida’s critique of J. L. Austin’s theory of ‘performative utterances’ in How to do Things with Words, Peggy Phelan defines a ‘performance’ as a unique and spontaneous event in the present tense that cannot be repeated or adequately captured on film or video.8 This radical notion of performance lies behind the hostility of some performance, site-specific and land artists to photo-documentation. ‘Performativity’, in contrast, signals an awareness of the way the present gesture is always an iteration or repetition of preceding acts. It therefore points to the collective dimension of speech and action. Of course, Derrida would object that there is no such thing as a ‘performance’ that is not a repetition, since ‘iterability is a structural characteristic of every mark’.9 For him, it is impossible to distinguish between citational statements on the one hand, and singular, original statements on the other. This is because an intention to say or do anything can never be entirely present to itself; there is always at work what he calls a ‘structural unconscious’.10 The distinction is nonetheless useful for thinking about different art practices and the aims associated with them. The term ‘performative’ is often used in critical writing in a less precise way to mean work with an element of performance, but I would like to see it reserved for the work of those artists who are interested in displacing spontaneity, self-expression and immediacy by putting into play repetition and the inherently iterative character of the instruction. The photographic practice I have in mind is also performative in the sense that the instruction makes something happen rather than describing a given state of affairs. Performative photography involves the partial abdication of authorial control, in favour of accident, chance or unforeseen circumstances. It is no wonder, then, that many of the artists interested in this kind of photography, like Vito Acconci, soon turned to video.

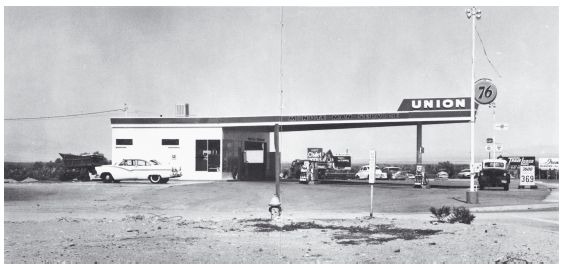

All this seems to me highly pertinent to the case of Ruscha’s books. His groundbreaking book of 1963, Twentysix Gasoline Stations, consists of photographs of gas stations along Route 66 between Los Angles and Oklahoma City (plate 2). The route is a relatively straight line on a map that he followed in his car.11 Ruscha set himself a simple brief – to photograph the gas stations en route – and he understood the photographs as records of these large-scale readymades. Deper-sonalization, both in the pre-set project and the uninflected snapshots, overlays what is, in fact, a record of anti-landmarks or poor monuments along the route home. Particularly pertinent in this context is Ruscha’s comment that he thought of the title first. In an interview with John Coplans for Artforum in 1965, he remarked that the work began as ‘a play on words’: he liked the word ‘gasoline’ and the specific quantity ‘twenty-six’.12 The design for the cover was finished before a single photograph was taken. Given the title’s priority, it can readily be understood as a contracted form of an instruction: ‘record 26 gasoline stations along Route 66’.

An early precedent for ‘instructional’ works of art is Duchamp’s important 3 Standard Stoppages of 1913–14 which consists of three gently curving threads, each one affixed to a panel, and three wooden templates or rulers formed in accordance with these wavy lines (plate 3). Like Twentysix Gasoline Stations, the title of Duchamp’s work has the same random specificity of a number followed by a qualifier and plural noun. If the similarity of the titles seems a tenuous link, it can be made more robust by pointing to a collage Ruscha made in 1960, called Three Standard Envelopes – clearly intended as a homage to Duchamp, although it actually resembles a Rauschenberg more. Furthermore, Duchamp’s work is framed by an instruction and cannot be properly understood without it. Unlike Ruscha’s contracted instructions, however, it is a rather elaborate one from the box of notes for the year 1913: ‘– If a straight horizontal thread one meter long falls from a height of one meter onto a horizontal plane distorting itself as it pleases and creates a new shape of the unit of length. – 3 patterns obtained in more of less similar conditions: considered in relation to one another they are an approximate reconstitution of a measure of length.’13 The comparison with Duchamp’s Stoppages highlights the mock-experimental character of Ruscha’s books. The instruction dictates the initial conditions of the experiment, but it does not determine the outcome. On the contrary, the instruction is a device for evading authorial or artistic agency and generating chance operations and unanticipated outcomes – the work thus displays what Duchamp called in his notes, ‘canned chance’.14 Duchamp’s little experiment did not involve photography, but he was fully aware of the significance of the camera as an apparatus apparently designed to generate chance effects and unexpected outcomes. Although sophisticated cameras are designed to produce predictable pictures in the hands of a skilled photographer, the automaticity or mechanical nature of the process lends itself to unintended happy (or unhappy) accidents. As Walker Evans so eloquently put it, the camera excels at ‘reflecting swift chance, disarray, wonder, and experiment’.15 There is an intrinsic connection, then, between the instructional means of short-circuiting authorial agency, of ensuring non-interference, and a certain use of the medium of photography.16 Photography, or at least this particular snapshot use of photography, brings together authorial abnegation, indexicality and openness to chance. Ruscha refers at one point to its ‘inhuman aspect’, as it records without making qualitative judgments.17

3 Marcel Duchamp, 3 Standard Stoppages (3 stoppages étalon), 1913–14. Assemblage: three threads glued to three painted canvas strips; three wood slates shaped along one edge to match the curves of the threads; the whole fitted into wood box. Replica, 1964. London: Tate Modern. Photo: © Tate, London 2009/DACS, London.

It is because Twentysix Gasoline Stations has a rule-governed, performative, character that comparisons with Evans, Robert Frank and other photographers of American vernacular scenes are so unilluminating. Robert Frank’s The Americans was published in 1959, only four year prior to Twentysix Gasoline Stations, yet there is a world of difference between it and Ruscha’s books. First, Ruscha largely excluded people and cars from his photographs; Frank’s pictures are almost entirely made up of people and cars. Second, Frank directs our attention with pointed juxtapositions to the social inequalities that existed across America; Ruscha aims at neutral recording – just ‘facts’, as he puts it. Finally, judged by the standards set by Frank, Evans and other masters of the medium, Ruscha’s snapshots are just pretty poor quality. But it is crucial to bear in mind that Ruscha was engaged in a radically different kind of artistic activity – that is, following a predetermined route in his car and systematically recording just the gas stations. This pervasive auto-maticity (instruction, car, route, camera) is what makes the book something new and strange. Or perhaps not so new and strange – maybe something more like a hybrid of current American and early avant-garde French artistic trends. Consider Ruscha’s response to one interviewer when asked about the influence of his sojourn in Paris. He said he didn’t like Picasso as much as Apollinaire, Duchamp, Man Ray and Picabia.18 The design of the book is also very French (see plate 1). It is white with red lettering wrapped in a protective glassine dust jacket. I imagine that when Ruscha visited Paris, he was struck by this spare, distinctively French, standard book design. He remarks, ‘I was interested in small books and I travelled to Europe and saw books over there very unlike the ones here. I just like the feel of them.’19 The emphasis Ruscha put on the typography and all-over graphic design of his covers, almost mini-concrete poems, distinguishes them from the Fluxus event score, which was not considered the locus of the work.

Although Ruscha’s photographs, viewed individually and in isolation from their proper context in the books, may seem to mime the amateur, my argument implies that this is hardly an adequate account of the project of the books. In his well-known essay, ‘‘‘Marks of Indifference’’: Aspects of Photography in or as Contemporary Art’, Jeff Wall offers an interpretation of Ruscha’s work as an imitation of amateur photography, in the same way as he regards Robert Smithson’s use of photography as a parodic imitation of photo-journalism.20 Positioning the photographic work of Ruscha, Smithson and Dan Graham, among others, in relation to these non-autonomous and un-aesthetic photographic practices helps to explain some of its character, but the operation of parodying has to do an awful lot of work. It does not quite capture Ruscha’s characteristic affectless, depersonalized, uninflected, use of the camera. In my view, the photographs are better viewed as the outcome of a rule-governed performance. Ruscha describes his approach to the making of a book as a ‘pre-meditated’ ‘self-assignment’.21 One of the many interviewers who try to induce Rushca to talk about his ‘vision’ gets a typically deflating but significant reply: ‘The attitude is just following through, following through with a feeling of blind faith that I had from the beginning. . . . The books were easy to do once I had a format. . . . Each one had to be plugged into the system I had.’22 This is clearly not the language of an amateur ‘everyman’ or even a parodic version of one. It is rather the idiom of an artist who has discovered a new medium and is busy unfolding its implications in a particularly systematic way. As Kevin Hatch observes, although Ruscha’s books may start with an idea, the work far exceeds the idea.23

The interpretation of Ruscha’s books as the products of rule-governed performances was very briefly adumbrated by Rosalind Krauss in ‘‘‘Specific’’ Objects’, an essay from 2004 which formed a part of her project of re-thinking the idea of the medium. After proposing, half-jokingly, that the car might be considered the element that forms a link between all his books, she puts forward another idea of his medium when she draws attention, as I have done, to the priority of the book titles. She qoutes Ruscha: ‘I had this idea for a book title – Twentysix Gasoline Stations – and it became like a fantasy rule in my mind that I had to follow.’24 Krauss concludes, ‘so for him medium has less to do with the physi-cality of the support than the system of ‘‘rules’’’. Oddly, Krauss does not link this medium with the long-standing artistic tradition of instructional-performative practices, but rather regards this arbitrary self-setting of rules as ‘necessary once the artist finds himself cut free of tradition and wandering haplessly in a field where ‘‘anything goes’’’.25

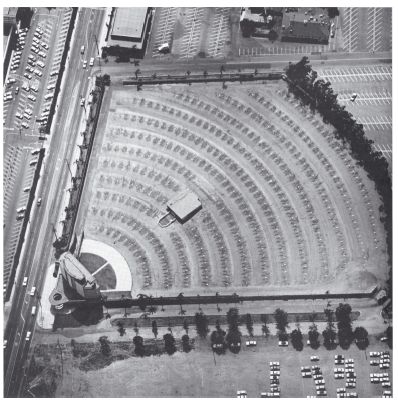

4 Ed Ruscha, ‘Gilmore Drive-in Theatre, 6201 W. 3rd St.’, from Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles, 1967. Photo: © Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles, 1967, is a particularly good example of Ruscha’s systematic strategy, even though the assignment is here delegated (plate 4). He gave an aerial photographer instructions to record empty parking lots around Los Angeles on a Sunday. The variety of abstract herring bone patterns is striking, but Ruscha said that what really pleased him was the way the experiment revealed unexpected traces of absent cars in the patterns of variegated oil stains. In an interview in 1972, he pointed out to David Bourdon how ‘the largest and most saturated spots indicate which spaces are the most favoured and parked upon’.26 This remark clearly indicates that the pictures are intended to be looked at – not exactly as aesthetic objects, but as documents conveying the results of his experiment. In all the books, aesthetic value is largely displaced onto their stylish typography, careful layout and tactile charm. The early books, including this one, are diminutive: only 7 × 51/2 inches. Every Building on Sunset Strip (1966), consisting of continuous motorized photos of both sides of the street printed on a twenty-five foot accordion-fold page, came housed in a box covered in reflective silver paper – miming the surface glamour of chrome. Ruscha is conscious that the books are as close as his work ever gets to existing in three dimensions, that is, as sculpture. Perhaps it is redundant to note here that I am not in agreement with interpretations of Ruscha’s work that take him to be a latter-day Theodor Adorno investigating the mass-produced uniformity of our late capitalist age. His attention to the detail of the visible world and his evident enjoyment of the Los Angeles landscape preclude such a view. Speaking of the city, he remarks, ‘I love it. I still get lifeblood from this place.’27 The banal character of the photographs is often remarked, but Ruscha’s word for this distinctive quality is not banal but ‘neutral’. For example, he says that people and cars are not neutral enough for his taste. This seems to suggest a Duchampian ‘beauty of indifference’ and perhaps also a sense that such loaded subjects would draw attention to themselves as depictions and thus destroy the aesthetic integrity of the books’ overall design as objects. One critic put this point well, noting with regard to Some Los Angeles Apartments (1965), ‘his primary concern was not how to look at an apartment building, but rather how to experience a book that contained snapshots of apartments.’28

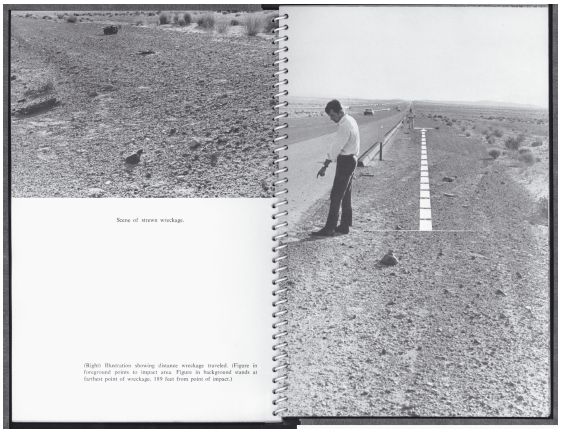

5 Ed Ruscha, Spread from Royal Road Test, 1967. Photo: © Ed Ruscha. Courtesy: Gagosian Gallery.

The book that declares itself most obviously as an instance of instructional-performative photography is the collaborative project Royal Road Test of 1967 (plate 5). Its experimental character is signalled in the title and its content is also more obviously the record of a performance. Ruscha says that Mason Williams spontaneously threw a typewriter out of a speeding car window and only later did they decide to go back and record the wreckage, but the book is presented as a totally pre-meditated, performative, instructional piece. In fact, the first photograph in the book shows a Royal typewriter sitting quietly on a desktop.29 The effect of the performance – the wreckage strewn across the Arizona desert – is carefully documented as if it were the scene of a crime. Many of the overhead shots resemble the Man Ray/Duchamp photograph Dust Breeding (in which, conversely, the dusty horizontal Large Glass is made to look like a desert landscape). The fragments of an unrecognizable mechanical apparatus strewn across the landscape only reinforce this impression. The last photograph shows the shadows of the three ‘bachelors’ (identified generically as driver, thrower and photographer) pointing at the twisted body of the mechanical ‘bride’.

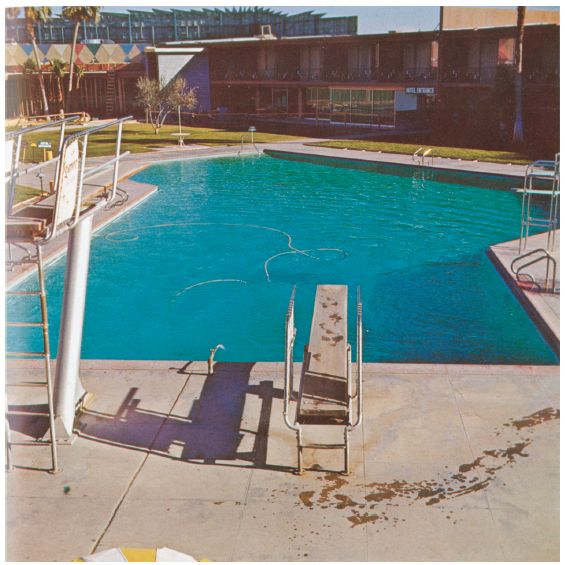

A similar indexation of a performer just outside the frame occurs in Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass (1968), where the photographed pools mirror palm trees, umbrellas and whole apartment blocks. In one, wet footprints leading to the diving board and ripples in the water indicate, like clues, the recent presence of a diver (plate 6). All of Ruscha’s books, except of course Every Building on Sunset Strip (1966), have blank pages. There are aesthetic and practical reasons for this: he remarked that he wanted Nine Swimming Pools to have a certain weight and thickness and the cheapest layout of ten colour plates over sixty-four pages is what dictated the rhythm of photographs and blank pages. He also said that he could have added a few more photographs at no extra expense, but he liked the number nine.30 In addition, the blank pages also serve to make one aware of the book as a physical object, not just a vehicle for photographs and text.

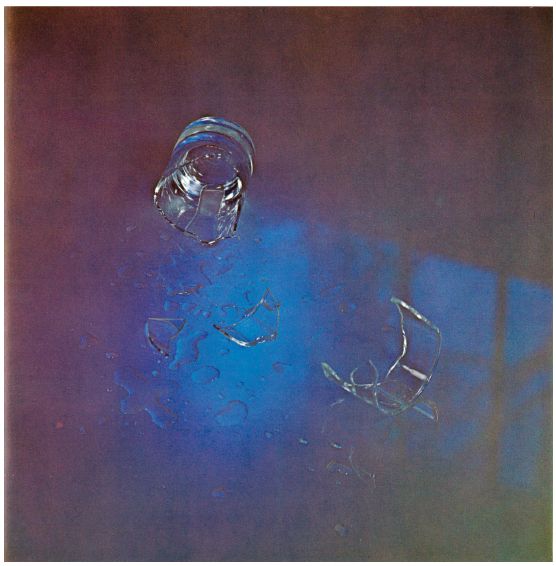

I like to think of Nine Swimming Pools as Ruscha’s wry tribute to Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (1915–23), generally referred to as the Large Glass.31 The pools, like the Glass, are both transparent and reflective, but it is the tenth incongruous photograph that hints at a link. The desire these glossy colour pictures of empty pools inspires is brought to an abrupt end by the final photograph of a broken glass – the fate that befell Duchamp’s Glass in 1926 (plate 7). Ruscha’s insistence on the number nine might then be plausibly explained as an oblique reference to the Nine Malic Moulds in the lower register of the Glass – the Moulds were, after all, conceived as variously shaped hollow forms.32 Some of Ruscha’s other works might be thought to refer to more recent precedents. Various Small Fires and Milk (1964) recalls a Fluxus event performed the same year by George Brecht in the Fluxhall/Fluxshop in New York City. The piece by La Monte Young, Composition 1960 #2 (‘Build a fire in front of the audience ...’), as minimally performed by Brecht, involved lighting a book of matches. The sixth image in Ruscha’s book is a flaming book of matches. Although my main point about Ruscha’s photography is that the photographic act is crucially altered by its re-functioning as part of a performative exercise, many of the photographs in this book actually document miniperformances, particularly those that show that rare thing in any Ruscha work, people – here, a young woman smoking a cigarette and a man smoking a cigar. However, because of the heterogeneous and rather random nature of the small fires, the book does not have the satisfying rigour of Gasoline Stations, Parking Lots or Pools.

Brecht’s work is particularly interesting in this context for several reasons. For a start, he obviously took great care with the graphic design of his ‘event scores’ on index cards. See, for example, his spare design for Word Event (Spring, 1961) which has a large bullet point centred on the card and then the word: • EXIT. The capitalization mimes the look of exit signs in public places in the USA, so performing the piece might be a matter of attending to that common sign with fresh eyes, either on the card or in situ or as a readymade sign offered for sale in Fluxus magazines. Another score, Two Signs, calls for a similar sustained attention to common signage: • Silence and • No Vacancy. Ruscha’s early word paintings of appropriated brand names such as Ace or Spam, both of 1962, are made in a similar spirit. Royal as printed on the cover of Royal Road Test, reproduces the distinctive logotype of the brand name. These examples suggest both a graphic designer’s appreciation of classic logotypes as well as a transgressive appropriation of pop culture.

6 Ed Ruscha, Spread from Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass, 1968 (pool). Photo: © Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

7 Ed Ruscha, Spread from Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass, 1968 (glass). Photo: © Ed Ruscha. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

The condition under which photography was acceptable as a medium for Ruscha, and for a number of other artists of this generation, was as a performative act executed in accordance with a set of instructions or simple brief. The photographs that result are the trace of the act and do not necessarily document a performance. Since the stress is on the photographic instantiation of an instruction (and not the instruction itself), they invite close inspection. In Rosalind Krauss’s influential account of the index in art of the 1970s, the index is understood as a sub-symbolic mark or trace requiring a supplemental text to anchor the sign. As we have seen, Ruscha’s photography reverses that relation. The text or title in Ruscha’s practice is a general, fairly empty or abstract instruction, while the photographs represent specific instances or realization. The photographs, then, serve to anchor language in a concrete, particular reality. Margit Rowell comes close to saying this in her catalogue essay for Ed Ruscha: Photographer. She identifies the two key factors of his photography as ‘the importance of the linguistic premise’ and ‘his personal interpretation of the "found" aesthetic’.33 I would like to specify these two points a bit further. First, it is not just language that is important for him, but something more like found poetry conveyed in visually arresting typography and graphic design. And, second, the link that he makes between words and his found objects is performative.

Before finally concluding, I want to touch on the work of a few artists whose use of photography might also be described as instructional and performative. I have written elsewhere about the early photographic practice of Vito Acconci, who incidentally began his career as a concrete poet, and of Sophie Calle, but they deserve mentioning again in this context.34 In his Following Piece (1969), Acconci set himself the task of following a randomly selected stranger walking in the street while he himself remained unobserved. The task ended when the person entered a private space. The performance was repeated every day for three weeks. Signalling the refusal of authorial control and corresponding receptivity, he called this activity ‘Performing myself through another agent’.35 The work is usually displayed with notes about the performance along with photographs, taken by a third party, of Acconci performing the work.

Ten years later, during the month of February 1979, the French artist Sophie Calle undertook her own following piece, Suite vénitienne. In some ways it resembles Acconci’s except that here the camera is more integrated into the activity.36 Calle decided to travel to Venice, track down a man she had met once at a party in Paris, and follow him. Because her choice of Henri B. was more or less arbitrary, her activity lacks the character of a stalking. Rather, Calle puts herself at the mercy of another.37 Sounding very like a latter day André Breton, she says: ‘I see myself at the labyrinth’s gate, ready to get lost in the city and in this story. Submissive.’ 38 The book form of the work consists of her stolen snapshots of Henri B.’s movements about the city and her diary.

The Belgian artist based in Mexico, Francis Alÿs, did a series called Doppleganger (2000) for which he devised the following instruction: ‘When arriving in . . . (new city), wander, looking for someone who could be you. If the meeting happens, walk beside your doppelgänger until your pace adjusts to his/hers.’ Photographs of rather unlikely looking suspects, taken from behind, are displayed with the text specifying the city. Alÿs’s video piece, If you are a Typical Spectator what you are really doing is Waiting for an Accident to Happen (1996), is also a sort of following piece. Alÿs trained his camera on an empty plastic bottle as it blew and was kicked by children around the great Zocalo square in Mexico City. The bottle strays into the street, Alÿs in hot pursuit, until . . . bang, crash, the world turns upside down as he is hit by a car. Despite its manifest differences, this video has all the characteristics I’ve highlighted in Ruscha’s books. It is a pre-meditated, instructional, performative video piece that involves following a rule, or a bottle, until the unexpected outcome – which in this case, turns out to be a Ruscha-like deflationary joke at the end.

What is the status of photography in these works? Can it be considered a medium at all? Ruscha has claimed more than once that he is not interested in photography as a medium, but by this I think he means that any attempt to position his books in the context of the history of photography is mistaken.39 This is because the books are not to be viewed as books of photographs; rather, they are three-dimensional works of art designed to be handled as well as viewed. Ruscha tried to convey this point visually with photographs and drawings of the books being handled (plate 1). In 1972, he made a drawing in gunpowder and pastel called, Three Hanging Books, which shows the books suspended by threads in midair. This is probably yet another reference to Duchamp who suspended his readymades from the ceiling of his studio.40 It is no wonder, then, that specialist theorists or historians of photography so often misunderstand the work. This includes Jeff Wall whose explanation of Ruscha’s photographic practice, and of conceptual photography more generally, as miming non-autonomous uses of the medium, whether amateur or journalistic, is not satisfactory. First, it diminishes the way the work relates to early avant-garde movements such as Dada and surrealism (by reducing them in turn to anti-aesthetic gestures). In those movements, the camera was often used to document a found or ready-made object, like the famous photographs of the slipper spoon and metal mask featured in Breton’s L’Amour fou. And they were often done in series, like the close-up photographs made by Brassal, probably at Dali’s instructions, of ‘involuntary sculptures’, the results of automatic manipulation of, for example, a ticket stub in a pocket. Second, and also following Dada and surrealist precedents, the photographic work discussed here found an outlet not as free-standing works of art to be sold in a gallery, but more often in mass-produced magazines or books: Ruscha’s books originally sold for around $3.00. Third, Wall’s theory does not adequately take into account the instructional and performative dimensions of this photographic practice. The photography discussed here is ‘conceptual’ only in so far as it is the result of following a rule or instruction in the spirit of experimentation, not knowing the outcome in advance. It may follow a preconceived rule, but it is open to unpredictable outcomes when the instruction is carried out. None of these strategies strikes me as reductive or anaesthetic. Rather, the aesthetic is reformulated by these artists in ways that accommodate different ideas of subjectivity, experience and art.41 In sum, photography after conceptual art should be viewed as refiguring photography away from high modernist paradigms and toward a model which revives the spirit of the early avant-gardes.

Notes

1 Ed Ruscha, Leave Any Information at the Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages, ed. and with an Introduction by Alexandra Schwartz, Cambridge, MA, 2003, 329.

2 The exhibition, By or of Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy, Pasadena Art Museum, October 1963, was curated by Walter Hopps, formerly of Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. It is also relevant to point out that the first monograph on Duchamp by Robert Lebel was translated and published in 1959. Lebel, Marcel Duchamp, trans. George Heard Hamilton, New York, 1959.

3 Ruscha, Leave, 300.

4 Ruscha, Leave, 216.

5 Liz Kotz, ‘Language between performance and photography’, in Kotz, Words to be Looked At: Language in 1960s Art, Cambridge, MA, 2007, ch. 5, 194.

6 Kotz, Words, 89.

7 See Sylvia Wolf, Ed Ruscha and Photography, New York, Whitney Museum of Contemporary Art, 2004; Ed Ruscha: Photographer, Whitney Museum of American Art, 2006, with an essay by Margit Rowell; Edward Ruscha: Editions, 1959–1999: Catalogue Raisonne’ [catalogue and] essays by Siri Engberg and Clive Phillpot, Minneapolis, The Walker Art Center, 1999; Ed Ruscha, The Works of Edward Ruscha, essays by Dave Hickey and Peter Plagens, introduction by Anne Livet, with a foreword by Henry T. Hopkins, San Francisco Museum of Art, 1982; Neal Benezra, Kerry Brougher; with a contribution by Phyllis Rosenzweig, Ed Ruscha, Washington, DC, Hirschhorn Museum, 2000.

8 Peggy Phelan, ‘Andy Warhol: performances of death in America’, in Performing the Body/ Performing the Text, eds Amelia Jones and Andrew Stephenson, London and New York, 1999, 223–37; and ‘The ontology of performance: representation without reproduction’, in Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, London and New York, 1993, 146–66. See also, J. L. Austin, How to do Things with Words (2nd edn), Cambridge, MA, 1975.

9 Jacques Derrida, ‘Signature event context’, Margins ofPhilosophy, trans. Alan Bass, Chicago, IL, 1982, 324.

10 Derrida, ‘Signature’, 326.

11 The arrangement of the photos is, however, not linear at all, as Eleanor Antin long ago pointed out. Eleanor Antin, ‘Reading Ruscha’, Art in America, 61: 6, November-December 1977, 69–70.

12 Ruscha, Leave, 23.

13 The complete instruction can be found in Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, eds, The Essential Writings of Marcel Duchamp, London, 1975, 22. See also Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors Even, a typographic version by Richard Hamilton of Marcel Duchamp’s Green Box, trans. George Heard Hamilton, New York, 1960.

14 One can well imagine Ruscha’s admiring the phrase ‘canned chance’. Brecht liked it so much he played on it in an installation called Iced Dice, at the Martin Jackson Gallery, New York.

15 Walker Evans, ‘The reappearance of photography’, in Alan Trachtenberg, ed., Classic Essays in Photography, New Haven and London, 1980, 185. Evans’ essay was originally published in 1931.

16 See Benjamin Buchloh’s interview with Robert Morris for Morris’s comments on his exactly contemporary attraction to the idea of instructional sculpture. Buchloh, ‘Three conversations in 1985: Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol and Robert Morris’, October, 70, Fall 1984, 33–54.

17 Ruscha, Leave, 170–1.

18 Ruscha, Leave, 120.

19 Ruscha, Leave, 216–17.

20 Jeff Wall, ‘‘‘Marks of indifference": aspects of photography in, or as, conceptual art’, in Ann Goldstein and Anne Rorimer, eds, Reconsidering the Object of Art: 1965–1975, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and Cambridge, MA, 1996.

21 Ruscha, Leave, 44.

22 Ruscha, Leave, 212.

23 Kevin Hatch, ‘‘‘Something else’’: Ed Ruscha’s photography books’, October, 111, Winter 2005, 124. The volume is devoted to essays on Ruscha.

24 Ruscha, Leave, 23.

25 Rosalind Krauss, ‘‘‘Specific’’ objects’, Res, 46, Autumn 2004, 222. She refers here to Stanley Cavell’s concept of ‘automatism’.

26 Ruscha, Leave, 43.

27 Ruscha, Leave, 123.

28 Richard D. Marshall, Ed Ruscha, London, 59.

29 Ruscha, explained this as follows: ‘The photo of the intact typewriter was added after the original one was thrown from the car. The act of throwing the typewriter was spontaneous and we re-created the before photo by finding a duplicate typewriter’ email correspondence 20 July 2009.

30 Ruscha, Leave, 44.

31 David Hockney’s painting, A Bigger Splash (1967), may also be a relevant reference in this context as it depicts a pool unpopulated except for a splash made by an invisible diver.

32 The search for Duchampian allusions in Ruscha’s work can become dangerously obsessive. Does his series called Stains (1969) made with a variety of non-paint or ink substances such as egg yolk, ‘Ketchup (Heinz)’ and ‘Sperm (human)’ allude to Duchamp’s work consisting of a spot of semen on dark cloth? Are the sheets of silk-screened chocolate he displayed in the Venice Biennale (Chocolate Room, 1970) anything to do with Duchamp’s Chocolate Grinder? (Use a chocolate grinder as a printing press.)

33 Margit Rowell, in Ruscha: Photographer, Whitney Museum of American Art, 2006, 39.

34 Margaret Iversen, ‘Following pieces: on performative photography’, in James Elkins, ed., Photography Theory, Cork and New York, 2006, 91–108.

35 See special issue on Acconci, Avalanche, 6, Fall 1972, 30.

36 In conversation with me and in other interviews, Calle has insisted that she was unaware of Acconci’s Following Piece when she made Suite vénitienne. However, after she’d taken the photos a friend told her about it. She made a trip to New York to visit Acconci who ‘gave her his blessing’. See the account of this episode in Cécile Camart, ‘Sophie Calle, 1978–1981: Genèse d’une fugure d’artiste’, Les Cahiers du Musée national d’art moderne, 85, Automne 2003, 64. See also the retrospective exhibition catalogue M’as-tu vue?, Pompidou Centre, Paris, 2003–4.

37 Yve-Alain Bois, ‘Character Study’, Artforum, April 2000, 126–31. See also his contribution to the Pompidou retrospective, ‘Paper Tiger’.

38 Sophie Calle, Suite Vénitienne, trans. Dany Barash and Danny Hatfield, Seattle, 1988, 6. Originally published in French under the same title, 1983. Also relevant is Breton’s account of his trailing of Jacqueline Lamba through the streets of Montmartre in Mad Love, trans. Mary Ann Caws, Lincoln, NE and London, 1987, 43.

39 Ruscha, Leave, 49.

40 It also recalls Duchamp’s Unhappy Readymade, 1919, which involved hanging a geometry textbook by strings from a balcony exposed to wind and rain.

41 Briony Fer has argued this case about the art of the 1970s in her book, The Infinite Line, where, for example, she notes that the use of repetition is not anaesthetic, but ‘provides the ground for this aesthetic terrain’. See Briony Fer, The Infinite Line, Yale and London, 2004, 158.