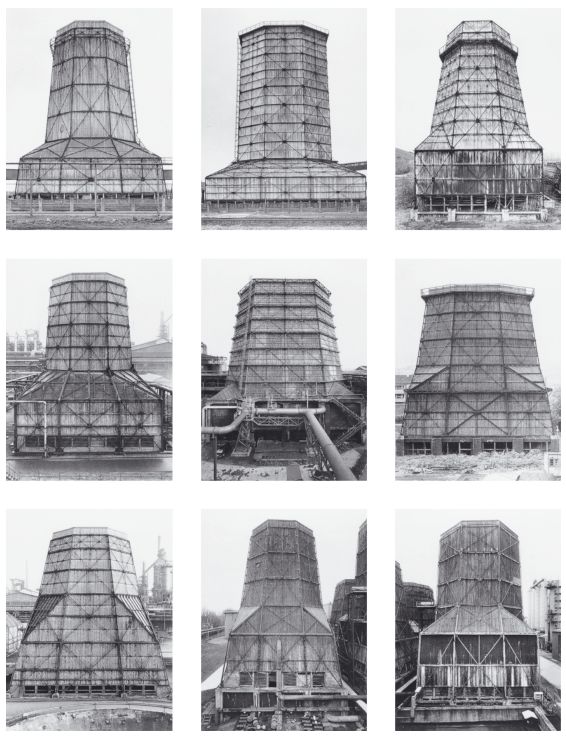

1 Bernd and Hilla Becher, Cooling Towers, 1967–1993, 2003. Nine black and white photographs, 173.36 × 142.88 cm. Photo: Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery.

4

SUBJECT, OBJECT, MIMESIS: THE AESTHETIC WORLD OF THE BECHERS’ PHOTOGRAPHY

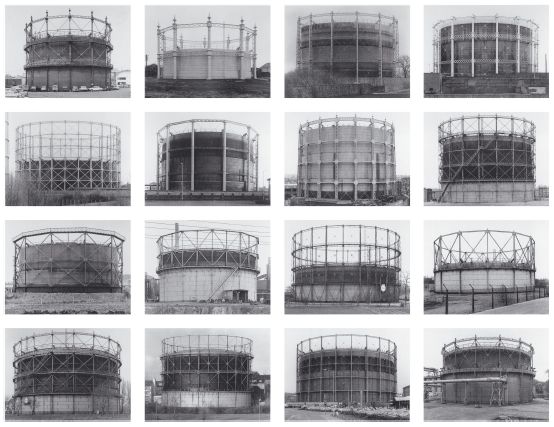

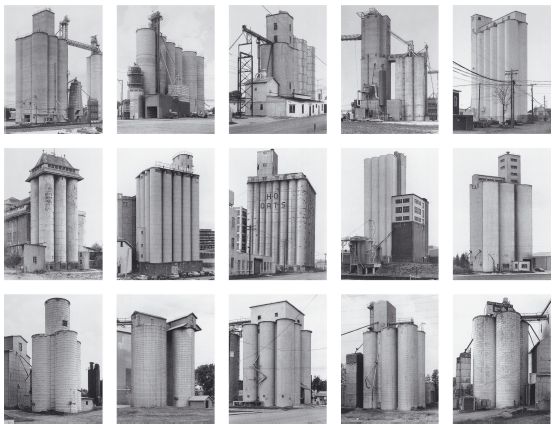

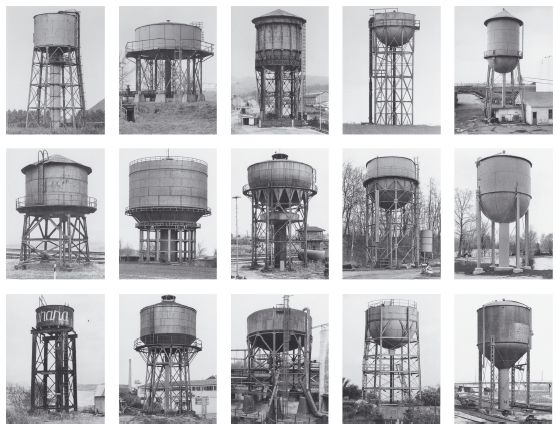

The structures in Coal Bunkers (plate 2) are redolent of a strange industrial family posing for their portraits. Their surfaces are bleached yet steeped in a dirty carbon patina, intersected by zigzagging stairwells, structural supports and sad vernacular flying buttresses. Broken windows and empty tracks testify to their dereliction, and the dimensionless, featureless sky, universalized by the camera, frames their type – like specimens pinned onto card, or anti-monuments. This grid of images is just one in hundreds of similar examples that belong to Bernd and Hilla Bechers’ vast photographic project. Begun in 1959 and coming to prominence in the 1970s, the Bechers’ work exists encyclopedically as a vast archive of typological grids of anonymous industrial architecture. For almost fifty years, the Bechers took standardized black and white photographs of industrial forms in Europe and America, from gasometers to grain elevators, factory facades and water towers (plates 1, and 3–5).1 An important impulse within their work is found in their aim to record the structures of a rapidly declining industrial era before they were lost for ever.2 Their practice shares some affinities with industrial archaeology in their compilation of an immense archive of industrial structures, a visual library of a disappearing industrial heritage. However, although the forms the Bechers depict are clearly epochal, they are not illustrative of the architecture of a specific author, moment or geographical region.

Above all else, the photographic world of the Bechers is committed to objectivity. Their consistent, arguably impossible, aim has been to evacuate their own subjectivity from the work, to remove themselves as expressive agents as much as is humanly possible from the photographic act. This difficult and disciplined form of expression is achieved in the strict adoption of a constant, straight, composition, unchanged over nearly half a century. All of their photographs are taken, when possible, from a height half that of the object, with a wide-angle lens, presenting the object frontally – a perspective that causes the horizon to recede and the surroundings to become more panoramic – giving the impression of distancing the object from its background, yet planting it firmly on the ground, and removing any sense of comparative scale. From 1961 they used a 13 × 18cm plate camera, and after that a modern large format camera, to capture the details of their subjects with precision. The structures are shown tightly framed, photographed on spring or autumn mornings under uniformly overcast skies in order to minimize shadows. There is less nostalgia, or feeling of potential, than we find in Eugene Atget’s deserted Parisian streets, less psychology than in August Sander’s portraits, and a more clinical photographic world of industrial buildings than was recorded by Albert Renger-Patzsch. The Bechers hope to achieve an impersonal aesthetic by presenting their object mutely, without implicating it in their own vision. As Hilla Becher has stated, ‘you have to be honest with your object to make sure that you do not destroy it with your subjectivity, and yet remain involved at the same time.’3 Their banishing of individual subjectivity is heightened in the act of their artistic collaboration, whereby, as in Bertholt Brecht’s poem, ‘Reader for Those Who Live in Cities’, the subjective ‘I’ of the artist dissolves into the more generic ‘We’.4 The objectivity of the Bechers’ photography is further developed through the avoidance of human subjects. As if following Walter Benjamin’s lament that ‘to do without people is for photography the most impossible of renunciations,’ their consistently depopulated photographs accept precisely this burden.5 Benjamin H. D. Buchloh has argued that in contemporary photographic practice the exclusion of figures and faces has now become a photographic strategy as significant as their traditional inclusion had once been.6 Buchloch perceives this photographic refusal of the subject, understood as a denial of the social, as ‘potentially renewing the photographic medium of the picturesque; its elimination of social reality, confirming a “melancholic complicity”, and engaging in a very picturesque abandonment and social passivity’.7 However, the Bechers’ work does not withdraw from the political into the picturesque, and their aesthetic world is fundamentally social.

2 Bernd and Hilla Becher, Gas Tanks, 1963–1997, 2003. Sixteen black and white photographs, 193.04 × 233.68 cm. Photo: Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery.

3 Bemd and Hilla Becher, Grain Elevators, 1982–2002, 2003. Fifteen black and white photographs, 173.36 × 239.4 cm. Photo: Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery.

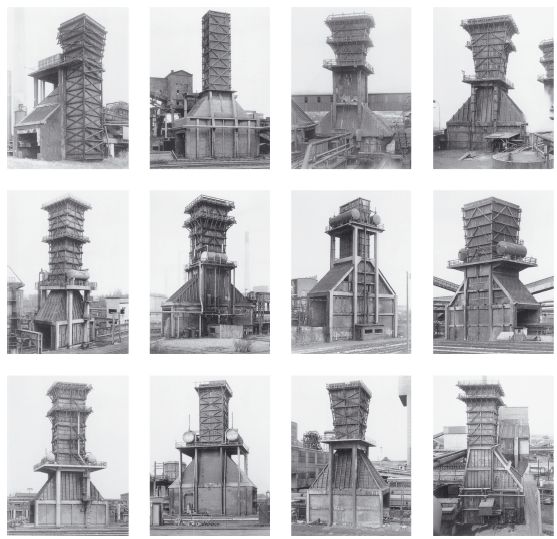

In the Bechers’ photography, the situation of the speaking subject is rejected in favour of the more generic statement or archive. The immense scope of the Bechers’ project abstracts the objects they depict and seems to eclipse the artists behind it. Their work relies on the conventions of photography, which provide their system, and it is this system and archival impulse that defines their oeuvre. The objects photographed are grouped together in grids, defined by the similarity of their structures. This system was set in place around 1966, when they decided on typologies of sets of nine and started to fully systematize types. They first used the term typology as the subtitle for their 1969 book Anonymous Sculptures.8 Although the number of images contained in the different grids alters, the typological presentation of their work is adhered to both in the book-format of their photography and when they exhibit it.9 The typological arrangement of their photographs enables the viewer to sense the similarities between each and the emergence of a generic type, whilst simultaneously registering all of the differences between the structures and their eccentric characteristics. For example, in the Cooling Towers (plate 6) series we are presented with a group of similar geometric three-dimensional forms, past sculptures of modernity, evoking deserted urban temples. The forms share fragile exteriors, all have three sides visible, and the corrugated iron skins of each are overlaid with the criss-cross geometric exoskeletons of their supporting architecture. Hilla Becher has commented that the essence of the objects under their lens can only be grasped and translated into the ‘typical form’ from the correct standpoint.10 Their photography is not interested in specificities. Rather the Bechers minimize both temporal and geographical clues and provide a similar scale for all of their objects. In seeking to illuminate generic similarities and ‘ideal types’, they have suggested, ‘the groups of photographs are more about similarities than distinctions . . . by looking at the photographs simultaneously, you store the knowledge of an ideal type, which can be used next time.’11 The cumulative effect of the series defines our reading. Yet, although it increases our knowledge of the subject matter, the work paradoxically renders it increasingly abstract.

4 Bernd and Hilla Becher, Industrial Facades, 1967–1992, 2003. Twelve black and white photographs, 173.36 × 191.14 cm. Photo: Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery.

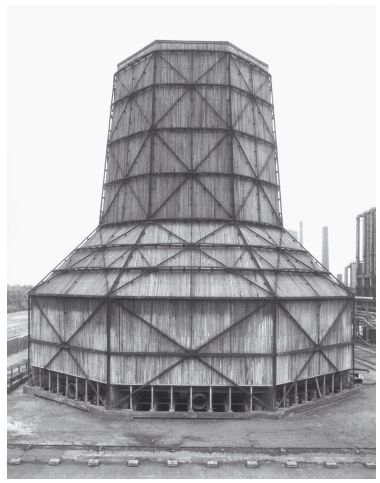

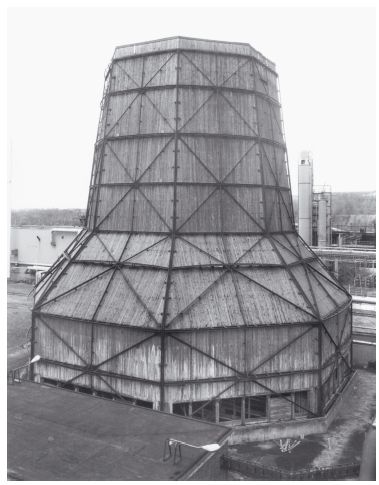

On one level the Bechers’ oeuvre operates as an entirely photographic world of anonymous sculptural forms. Although true to their subjects in a documentary sense, their photographs of coal bunkers or water towers are not orthodox documentary images. There is no narrative. The everyday is abstracted, punctuated by seriality, and the structures are aestheticized, made reminiscent of beautiful relics or functionalist sculptures. That thirty years might separate two of their photographs is a fact obliterated by the similarities of the structures’ anonymous scaffolding, and their identical, clinical, presentation (plates 7 and 8). That the Bechers’ repetitive project spans nearly half a century gives their work a very unusual historical status, a complex temporal dynamic of its own. A single photograph by the Bechers looks lonely. Their work exists as both a pre-history to much of the critical photographic seriality that dominated the conceptualism of the 1960s and 1970s, and as a never-ending afterword to that period. Yet in its explicitly aesthetic dimension their work remains perplexingly incompatible with conceptualism’s central objectives.

5 Bernd and Hilla Becher, Water Towers, 1967–1983, 2003. Fifteen black and white photographs, 173.36 × 239.4 cm. Photo: Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery.

The complex aesthetic world of the Bechers and the ontological work that animates it has recently been the subject of investigations by both Blake Stimson and Michael Fried.12 Although divergent in their agendas, and consequently in how they frame their readings, both Stimson and Fried have rightly argued that the Bechers’ aesthetic is intrinsically linked to a way of seeing, and, consequently, to a way of knowing. Stimson’s approach to the Bechers is determined by his reading of photography in the post-war period of the 1950s as ‘social form’, related to what he views as the preoccupation of the time with a ‘new concept of man’.13 For Stimson, photography in this decade enabled a reworking of the ideals of the ‘New Vision’, and the relationship between the individual and the world that allowed for a rethinking of the concept of nation. By placing the Bechers’ project alongside Edward Steichen’s The Family of Man exhibition of 1955 and Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958), Stimson proposes that all three can be understood as working to ‘release the dream of nation’ – of belonging and sovereignty – from its old civic constraints, enabling ‘an opening to negotiation or conciliation with collectivism, a manner of tapping into collective expression and identification in a manner that shared in its recognizable affective force while still effectively tempering its potential for political violence’.14 Although inattentive to the different cultural contexts of these American and German practices, for Stimson, seriality is central in all three of his examples, opening up new possibilities for social form. It does so, he argues, because the separation of frames that defines serial photography does not allow each to be displaced by the next in a narrative or temporal structure, and instead generates tensions between the general and particular, distance and proximity. This serial form consequently produces a ‘photography qua photography’ that represents its own autonomous place, stance, and identity in the world.

6 Bernd and Hilla Becher, Coal Bunkers, 1967–1998, 2003. Twelve black and white photographs, 173.36 × 191.14 cm. Photo: Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery.

The Bechers’ photography is presented by Stimson as dislodging earlier modernist political ideals, while delighting in some of their utopian impulses. From this perspective, the Bechers’ project can be understood as proffering its own system of value, and thereby a distinctive form of autonomy and a model of sociality. The experience of their work is realized as ‘satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) in the object without any specific individual aim or instrumental purpose being satisfied (or frustrated), without any notion of individual interest or collective will’.15 It is this that makes the experience of the Bechers’ work generalized and universal, and, for Stimson, a kind of ‘neo-Kantian judgment made melancholy, a fully developed archive structured around an absent ideal’.16 He suggests that the Bechers’ industrial photography thus deploys the original Enlightenment promise of aesthetics: the ability to judge without interest.17 In order to analyse the rhythms and repetitions of the Bechers’ photography, Stimson considers the ‘grammar’ of their work as ‘embodied expression’ and ‘a symptom of a social relation’.18 The ‘photographic comportment’ of the Bechers is, he insists, ‘a mode of being in, or perhaps better, a mode of being with the world more than it is a mode of representing it’.19 Stimson concludes with reference to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, and the philosopher’s suggestion that one should respond to the experience of knowledge as abstraction ‘not so much in purging the individual of an immediate, sensuous mode of apprehension, and making him into a substance that is an object of thought and that thinks, but rather in just the opposite, in freeing determinate thoughts from their fixity’.20 This great modernist aim, Stimson claims, is located in the Bechers’ serial photography, which frees embodiment from self-consciousness and in so doing, expresses a new form of political subjectivity.21

Like Stimson, Fried sees the Bechers’ work as engaged not simply in a mode of apprehension, but in a rather more comparative and intellectually active kind of seeing. If Stimson is largely preoccupied with the subject-experience produced by the Bechers’ photography, Fried is primarily concerned with the philosophical status of the object in their work. Fried suggests that the ontological originality of their project lies in its typologizing approach and the inseparability of similarity and difference in their photography – the acknowledgement of the simultaneous relations of resemblance and difference between the diverse structures that they photograph. Comparing their photography’s relationship to the objects depicted with his own reading of minimalist objecthood, Fried argues that a different kind of objecthood is in play here. Like Stimson, in theorizing the aesthetic experiences contained within the Bechers’ photography, Fried looks to Hegel, but not to his phenomenological writings. For Fried it is the philosopher’s Science of Logic that becomes central.22 Relying heavily upon Robert Pippin’s reading of Hegel, Fried proposes that the Bechers’ work can be illuminated by an appeal to Hegel’s distinction between the notions of the ‘genuine’ or ‘true’ infinite, and the ‘spurious’ or ‘bad’ infinite.23 What is at stake in this distinction, Fried suggests, is how to ‘specify the finitude or individuality of objects in a way that does not simply contrast all the characteristics that a particular object allegedly possesses with all other possible characteristics that it does not’.24 Therefore, it becomes possible to think of the Bechers’ photography as aiming not to represent the ground or field against which the photographed objects in question stand out but, more modestly, the ‘making intuitable of the conditions of their intelligibility both as the types of objects they instantiate – water towers, cooling towers, gasometers, winding towers, and so on – and as the particular instance of those types that the viewer is invited to recognize them as being’.25 In other words, in creating their typologizing system, the Bechers remove each object from the spurious infinity of all objects in the world and give them specificity. At the same time, Fried stresses, the internally contrastive nature of their system means that each object is compared with the others, positively inviting spontaneous and structured comparisons. This way of comprehending becomes Hegelian because, like Hegel, the Bechers make clear that any attempt to identify or differentiate an essence is always necessarily indeterminate. The incompleteness of their ever-extending archive is an example of what Hegel called a ‘genuine infinity’, while the objects of the Bechers’ typologies can be said to exemplify ‘good objecthood’.26 If the work of art is seen sub specie aeternitatis (‘from the perspective of the eternal’), and the everyday object is seen from ‘out of their midst’, then the manner of beholding that the Bechers’ photography instigates sees the objects from the outside, but in such a way that they have the whole world as a background. With the aid of Wittgenstein’s pre-Tractatus notebooks of 1916, Fried suggests that this kind of beholding involves the consideration of varieties of ‘objecthood, worldhood and logical space that have nothing esthetic about them, in the traditional sense of the word’.27

7 Bernd and Hilla Becher, Cooling Tower, Rheim/Moers, Ruhrgebiet, Germany, 1963. Black and white photograph, 50 × 60 cm. Photo: Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery.

8 Bernd and Hilla Becher,Cooling Tower, Dortmund, Ruhrgebiet, Germany, 1993. Black and white photograph, 50 × 60 cm. Photo: Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery.

If for Stimson the aesthetic experience of the Bechers’ photography is one that grounds the beholder in and with the world, and ultimately articulates an archetypal ur-aesthetics, for Fried it engenders a seeing of objects ‘from the outside’, instead of from out of their midst, in relation to logical space as a whole. For Fried this is closer to what he calls elsewhere an ‘aesthetics without aesthetics’.28 Both accounts make clear that the objective character of the Bechers’ photography, and the mode of seeing that their work instigates, enables their project to be both aesthetic and ethical. Yet on its own, neither account seems quite complete, focused as they both are primarily on subjecthood and objecthood, respectively. In what follows, I want to bring together their respective examinations of the subject and object within the aesthetic experience of the Bechers’ practice. Building on Stimson’s and Fried’s readings, I want to suggest that the aesthetic thought of Theodor W. Adorno, and particularly his concept of mimesis, provides a productive conceptual framework from which to interrogate and transcend this separation of subject and object positions within the Bechers’ photographic world.

Crucially, a consideration of Adorno’s philosophy serves to draw attention to the fact that there is a marked absence in both Stimson’s and Fried’s accounts – albeit to a lesser degree in Stimson’s – of any extended engagement with the specifically German historical character of the Bechers’ photography and the aesthetic experience it generates. There is something historically significant about the Bechers’ work, and the ways in which this impacts upon the form of subjectivity and objecthood articulated in their photography has yet to be fully clarified. The historical condition of their photography is simply omitted from Fried’s account, and although Stimson productively situates their work in the post-war period and the ‘end of ideologies’ debates that coloured the 1950s, his international approach fails to examine fully the culturally specific experience of Germany throughout that decade. Adorno was one of Germany’s most important post-war philosophers and in his late writings, which are contemporaneous with the beginnings of the Bechers’ typological project, one is granted both a valuable insight into a critical juncture in German history, and a crucial framework for thinking through the aesthetic experience contained within their photography. For here Adorno attempts to reformulate aesthetics after the decline of modernism, the rise of Fascism, the spread of capitalism and the catastrophe of the Holocaust.29

While many critics have rightly drawn parallels between the work of the Bechers and their modernist Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) forbears, the fact that the Bechers’ oeuvre is also both strongly a response to, and a product of, the post-war period in West Germany is too rarely noted. The Bechers’ photography is underwritten by their self-conscious rejection of the idea of art’s political or ideological function.30 They have stated frequently that their photography would not have been possible were it ideological. Hilla Becher has commented, ‘For me, photography is by its very nature free of ideology. Photography with ideology falls to pieces.’31 In the vernacular subject of past and anonymous industry, the Bechers believed that they had found a world as free of ideology as possible. Crucially, their subject was not Germany’s industrial heritage (which would necessarily have brought with it the more problematic burden of nationalism), but an anonymous and international architecture. The politics of their consistent rejection of ideology can only be understood in the specific cultural context also addressed by Adorno. One of the most striking characteristics of this post-war period was the depoliticization of German culture and society. The 1950s, when the Bechers began their collaborative photographic endeavour, have become known for many as a ‘dormant’ and materialist decade in the Federal Republic’s history, a time of conservative rehabilitation characterized by political sobriety and a rejection of ideologies.32 After the experience of Nazism, the destruction of the war and military occupation, the dominant mood in West Germany was one of disillusionment and mistrust, resignation and disinterest in politics. As Frank Biess has stated, ‘in the first post-war decade, West Germans sought to confront the consequences of Nazi ideological warfare within a distinctly de-ideologized and depoliticized framework.’33 Konrad Adenauer’s government championed the westernization of the new state and, embracing the rampant Americanization of German society, celebrated the birth of the consumer era and the Wirtschaftswunder (economic miracle). Because security and prosperity were the main objectives of the state, anti-communism and economic stability became its two only ideological creeds – ‘a sort of ersatz-ideology, for keeping together a basically apolitical population that [had] lost a sense of common political tradition on which consensus could be founded’.34 In the 1950s, West Germany was not alone, however, in its attempt to move beyond ideologies. As Stimson has stressed, intellectuals in the rest of Europe and America were also proclaiming the end of ideologies.35 In Germany though, this rejection of ideology was more nuanced. As Martin Kolinsky and William E. Paterson have argued, the trauma of the war and the experience of fascism ‘produced a political narcosis which not only resulted in an avoidance of, and withdrawal from, questions and problems involving the past and extremism, but also from political conflict, controversy and commitment in general’.36 As a result, throughout the 1950s and the early 1960s West German society was dominated by a pragmatic pluralism and a deep-seated fear of the political. As in the social sphere, in the cultural realm ‘ideology was an ill-omened word, associated with National Socialism, Stalinism and East Germany’.37 For example, West German literature of the 1950s possessed a political dimension only in the sense of being unwaveringly anti-fascist, while often embracing an apolitical existentialism and modest realism. Hans Meyer has aptly characterized such early post-war literature as an ‘ideology of anti-ideology’ (‘Ideologie der Ideologiefeindschaft’).38

On first inspection, then, the Bechers’ refusal of ideology appears to reflect the same sentiments as popular and intellectual currents in post-war West Germany, an ‘ideology of anti-ideology’. However, their work, in which they sought obsessively to banish the political, is not coloured by a simplistic apolitical existentialism, or by any sceptical assertions about the end of politics. Instead they recognize, as Adorno argued, that in a culture resurrected after catastrophe, ‘art has taken on an ideological aspect by its mere existence.’39 According to Adorno, the most fundamental form of ideology, serving perhaps as a kind of meta-theory of ideology, is ‘identity’ itself, involving the mindless repetition of sameness without reflection.40 If ideologies transform sentiment into significance through symbolism, metaphor and analogy, it is exactly through the attempt to remove the self that the Bechers’ photography seeks to reject ideology. In their epic project the Bechers pursue a commitment that could no longer be located in the individual or the masses, but that was nevertheless crucial to maintain if art were to justify its continued existence in a world for ever changed by Hitler’s Fascism and the Holocaust. The Bechers are not necessarily picturing a post-ideological or pragmatic world. I want to suggest that in working against identity, what the Bechers’ photography seeks is something closer to what Fredric Jameson has called the ‘non-ideological’ – the utopian moment at the centre of all ideology.41

The central paradox that lies at the core of the Bechers’ practice is that their work is aesthetic, whilst almost refusing to be art. Indeed, in the German context of the 1950s and 1960s, their photography often wasn’t perceived as art, but as the documentation and illustration of industrial archaeology, and many of their early commissions came from the industrial world. The Bechers’ deliberate refusal of ‘artistic’ photography can only be explained in light of the cultural taboo placed on artistic creation in Germany in the aftermath of the 1939–45 war and the catastrophe of the Holocaust, which initiated a retreat from the explicitly aesthetic, expressive and beautiful, and a movement towards documentary and realism. In examining the contemporary situation of art in Germany in the 1950s, Adorno believed that the essence of art as an autonomous sphere of value had become insufferable because of the increasingly rationalized world that had culminated in the horror of the Holocaust.42 Because of this, he argued, ‘art must turn against itself, in opposition to its own concept, and thus become uncertain of itself right to its innermost fibre.’43 In the photography of the Bechers this uncertainty is both apparent and ever-present; the kind of aesthetic experience it harbours suggests the untenable character of art, its borderline existence.44 The Bechers’ photography is invested in the aesthetic because it offers an invaluable alternative to the political. Crucially however, their aesthetic is neither the picturesque nor the lofty domain of the sublime. Rather it originates in the least artistic world imaginable. Aware of the impossibility of beauty after Auschwitz, they displace the beautiful with the industrial. Adorno anticipates precisely such a transposition when he states that art must now be ‘defined by its relation to what it is not. The specifically artistic in art must be derived concretely from its other; that alone would fulfill the demands of a materialistic-dialectical aesthetics.’45 The Bechers’ work proposes that artistic agency and aesthetic experience need another framework, and that such a basis might be found in industrial forms, in labour, and in history. The artists have stressed that the industrial world felt like an extension of their childhoods and part of their ancestry, that they already knew about the conditions and vocabulary of industry, and in their work became involved in its subculture and the people whose world it was. This is clearly reflected in their series of workers’ framework houses in Siegen’s industrial area (plate 9).46 This vernacular subject and the style of their photographic depictions enable the beholder, via a process of ‘determinate negation’ (an immanent criticism that contrasts its subject with other subjects determined in ways in which it is not) to think their photography both aesthetically and anti-aesthetically at the same time.

At this critical moment in post-war German history Adorno also addressed the unfeasibility of aesthetics, rewriting its impossibility back into a new version of itself through a negative dialectical approach.47 Adorno argued that the task that now fell to aesthetics was to foster the rational and concrete dissolution of conventional aesthetic categories in such a way as to release new truth content into these categories. A similar negative dialectic is enacted by the Bechers’ archive: they refuse to give up photography’s autonomy, and their systematized and abstract world of sculptural subjects affirms their attempt to offer art a weak promise of utopian transcendence. The Bechers do not reject the ideals of beauty and truth outright; in fact their photography attempts to redeem them – but only through forcing materialism upon metaphysics. In their work an aesthetic language is demanded, albeit one that is found in the foreign ornament and vernacular vocabulary of industry, rather than the traditional lexicon of art history. To talk in any detail about their images one must learn the language of industrial engineering: pithead towers, coke ovens, engine houses, gas compressors, central shafts, consolidation collieries, twin-strut frames, and steel headgear. Thus the Bechers put aesthetic experience to work. They make hermeneutics a process of labour, not transcendence, and traditional aesthetic concepts are pressed back into service dialectically.

9 Bernd and Hilla Becher, Framework Houses, 1996. Fifteen black and white photographs, 173 × 239 cm. Photo: Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery.

The Bechers’ rejection of the ideological and their refusal to depict the subject can be understood as a strategic refusal to participate in the photographic reifi-cation and ruin of subjectivity. Their reluctance to exert their artistic subjectivity, or to portray human subjects, can be understood as a reluctance to support the arrogance of individual vision or to make the individual human subject into a representative of either a collective type or a specific identity. The Bechers’ oeuvre originates in the acknowledgement that the experience of the subject – and its experience of nature – is historically deformed. As if following Michel Foucault’s warning that making historical analysis the discourse of the continuous, and making human consciousness the original subject of all historical development, are two sides of the same system of thought, the Bechers’ refusal of the centred subject’s authorial voice goes hand-in-hand with their rejection of a documentary photography that might reconstruct history or attempt to construct history itself.48 It is as if in their objective style and their typologizing, systematizing vision, they are registering the suspension of pre-existing forms of continuity and synthesis that are accepted without question, demonstrating through their practice that such systems of interpretation do not come about by themselves, but are always the result of a construction, the rules of which can be excavated.

The Bechers anthropomorphize and transform the industrial structures under their camera’s lens into objects, into things. Like Karl Blosslfeldt’s botanical specimens, these cultural-historical artefacts are almost presented as if they were natural forms. This is a process that might initially seem ideologically dubious, since it is the assimilation of culture to nature that underlies the formation of ideology; as a result, it is normally its inverse that is posited, the dissolution of the natural into the cultural, and the flat rejection of nature. However, an analogous process plays a central role in Benjamin’s philosophy – his ‘dialectics at a standstill’ – which Adorno in turn described as a ‘natural history’.49 Adorno claims that the Benjaminian ‘essay as form’ depended upon the philosopher’s astute ability to regard historical ‘moments’, ‘manifestations of the objective spirit’, and ‘culture’ as though they were natural.50 Similarly, the Bechers’ photography formalizes reification, depicting sites of human labour, monuments of the industrial revolution, and freezing these past gestures of labour – literally ‘thingifying’ them. In so doing, their photography operates as a visual pun on the abstraction of labour’s use value and the commodity fetishism that replaces inter-human relationships with relationships between humans and things. In this way their work echoes Benjamin’s appropriation of the fetishism of commodities, a strategy he pursues because, as Adorno asserts, ‘everything must metamorphose into a thing in order to break the catastrophic spell of things.’51 In the Bechers’ series of near-identical images the historical becomes natural, but at the same time their archive alternates between the general and the particular, the image and the thing, between difference and similarity.

Hence it is not the form of political subjectivity or the objecthood generated by the Bechers’ work, taken on its own, that is central to their photography, but the dialectical experience that takes place between them. Adorno attempted to think just such an experience in his concept of mimesis, defined as ‘the non-conceptual affinity of a subjective creation with its objective and unposited other’.52 Adorno turns to this concept in order to overcome the hierarchy between the subject and object, in which subjective reason dominates the object.53 Adorno’s ‘non-identitarian’ thinking, by contrast, resists the compulsion to identification inherent in all conceptual thought, its relentless subsumption of particulars under generalizing concepts, by continual self-reflection upon the inadequacy of such thought, approaching truth negatively. His aesthetic theory is a model of such thinking in action. Adorno’s negative, and always incomplete, dialectic begins, in opposition to Hegel’s, with the object rather than the subject, and attempts, in Tom Huhn’s words, to ‘follow, intellectually and experientially, the shape of certain objects, namely those that themselves seem irreducible to thoughts alone’.54

Huhn’s reading of Adorno’s conception of mimesis situates it in relation to the latter’s critique of subjectivity, and in this light we can understand it as the central term in his conception of the dialectical relations between subjectivity and its objects. In Adorno’s account, subjectivity’s development is a dialectical, historical process, and mimesis is the projection and reprojection of subjectivity. It is not the copying or imitation of what has been, but the continuity, from reflection to reflection, of the multiple aspects and movements of subjective possibility.55 As Huhn suggests, ‘the dialectical advantage of objectifying thought – like that of reifying subjectivity – is . . . not to revivify these ossified objects’, but instead, ‘to allow subjectivity to become, reflectively, something else in response to them’.56 For Hegel, the artwork’s inescapable objecthood constrains purely subjective experience and the artwork consequently becomes a mimetic projection of ‘where subjectivity might most productively flounder’.57 Nonetheless, for the subject to assimilate itself to the object requires, paradoxically, an active subject. Consequently, as Peter Osborne stresses, ‘In a work of art, the mimetic moment dialectically interpenetrates the rational, constructive moment (without ultimately being reconciled with it) in such a way that it is expressed through it, while nonetheless, through its difference from it, acting as a criticism of it.’58 Adorno argues that before the first image was produced, it was preceded by a mimetic act, the ‘assimilation of the self to its other’.59 Indeed, Adorno characterizes both art and mimesis in terms of ‘comportment’ (Verhalten) – a receptive mode of being and orienting oneself to the world – and states that ‘art in its innermost essence is a comportment.’60 It is a way of doing, rather than making.

As in Adorno’s aesthetic thought, so in the Bechers’ photography: subjectivity is extricated from organicist, expressivist and biographical notions, but not completely done away with.61 The Bechers’ work begins as a formal negativity; it occupies a classical conception of aesthetic experience of the object from within, provisionally accepting its methodological presuppositions, substantive premises, and truth-claims as its own. But their photography ultimately puts pressure on the premises and assertions of aesthetic experience. What underlies the aesthetics of the Bechers’ photography is also the strategic dissolution of the hierarchy that defines the relationship between the subject and the object. Indeed, echoing Adorno’s understanding of subject mediation, one might argue that the aesthetic experiences of the Bechers’ photography are based upon the subject’s active engagement with the object, and, specifically, with the role of the social totality within the object; an object that must be embedded in concrete, and historically specific, social existence. But their photography also elicits a productive floundering of the subject: their unfinished, incomplete photographic world invites reflection, subjective dissolution and reconstitution. In this light, the never-ending nature of the Bechers’ work takes on a weightier significance, and we can further appreciate Fried’s reading of their objecthood and Stimson’s interpretation of the Bechers’ photography as a sort of ur-aesthetic experience, not only because of the disinterestedness they cultivate, but because in their photography the subject is afforded a mimetic model which, like Adorno’s understanding of aesthetic experience more generally, enacts ‘the pitfalls of subjective becoming, of how to forestall becoming fixed and fixated, rigid and further bound up’.62

The ‘grammar’ of the Bechers’ work can be understood as ‘embodied expression’, and the form of comportment or bearing toward the world that their photography generates can be thought of as mimetic because it attempts to objectify without reification, to express without expressing something. The Bechers’ photography, as Stimson and Fried would agree, actively distances itself from making, and instead, is all about a way of doing. The ‘continuity of reflection’ is what enables the beholder of the Bechers’ photographic world to hold on to the memory of the ideal object in between every act of looking at the next. It is also what holds together the notion of an active and absent subject and an ideal but unachievable object. Thus, the subject positions produced in the Bechers’ photography emerge through the object; political subjectivity and objecthood are realized only through each other. If the Bechers’ work gestures towards the general, the ideal object and the absent subject, it constantly interrupts the possibility that they will ever be realized by reactivating their beholder to register difference, to look actively, to systematize. Seen in this light, it is the way that mimesis and construction dialectically combine in the production of the Bechers’ work that enables their aesthetic experience to aspire, albeit negatively, to an autonomous truth.

Thus, the Bechers’ photography can be understood as enabling us to construct another understanding of objectivity – one that is not immediately aligned with the construction of false histories and hidden ideologies. Rather it offers an objectivity that can be recast as something more fragile and discontinuous, something that is about a silent shared commonality, and something that might need to be protected. The aim of their work is comparative, drawn by the aesthetic language traced across their objects. And the beauty of their photography reveals itself as the product of persistent analysis. If morphology occupies a central place in their photography, it is not limited to the science of forms, but is closer to the branch of linguistics that studies patterns of word formation within and across languages, and attempts to formulate rules that model the knowledge of the speakers of those languages. Though it may appear easy to undercut the Bechers’ aspiration towards objectivity by arguing that the highest forms of latent subjective expression can be found in the very distinctive aesthetic of their work, looking at it through the lens of Adorno’s thought, one can argue that in mimetically evacuating their subjectivity, they deliberately make the subject perpetually present.

When the Bechers began their photographic project in Germany of the 1950s, a cultural prohibition against the subject was directly related to the postAuschwitz cultural critique of the individual. However, autonomy – the power of self-reflection, and self-determination, what Adorno referred to as ‘the single genuine power standing against the principle of Auschwitz’ – was understood as equally crucial at this juncture.63 The Bechers’ anti-subjectivism can be thought of like Adorno’s; it is driven by the idea that the true place of the subject in aesthetic experience is not to be characterized by its purification, ‘still less in its creative mastery over this last and objective contingency, but instead in a violent eclipse of the subject itself, with which comes its simultaneous affirmation’.64 The Bechers literally disappear into their photography. Just as objectivity is given an expressivity of its own, the act of removing themselves from their photographs, of removing all remnants of human subjects – and policing this in such an absolute manner – becomes somatic, physical, and real. It is a much more profound way of citing the subject. It is not, as Stimson argues, a conciliation with collectivism that their work initiates, but with the singular subject. The subject that simultaneously emerges is not the individual, but its ideal. The Bechers’ reject the subject that Adorno sees as resulting from the narcissistically self-related cultivation of its ‘being-for-itself, in favour of a process of externalization and the dialectical assertion of an absent and ideal subject. Or, as Adorno called it, ‘the moment of autonomy, freedom, and resistance that once, no matter how adulterated by ideology, resonated in the ideal of personality’.65

Both the ‘good objecthood’ that Fried finds in the Bechers’ photography, and the ‘comportment to the world’ located by Stimson, are a result of the artists’ mimetic attempt to redeem expression through the frail objectivity and historicity of things. In their avowedly objective photography, the Bechers’ seek to redeem a metaphysical or ‘emphatic’ concept of truth from the context of idealist ontology. But the ideal of the camera’s ability to depict truthfully, its power to represent absolutes, is redeemed precisely in its acknowledged failure to ever fully represent any truth. Each photograph within the Bechers’ never-ending photographic archive exists as a dialectic image, emerging between the alienation of the object and the meaning it acquires on being viewed. Their photography underlines the fact that there can be no knowledge without a perspective from which it is gained. The Bechers’ practice elaborates an aesthetic from below. In their desire to truthfully redeem the ‘thingness’ of the world, their photography enables the resurrection of a certain archaism – a moment where the subjective and the objective meet, and the mimesis of reification coexists with the mimetic resistance of reification.

Notes

1 The Bechers worked on this project collaboratively until Bernd Becher’s death on 22 June 2007.

2 Bernd Becher first photographed industry in Siegen in 1957, taking photographs of industrial structures that he was planning to paint as he could not keep up with their demolition by drawing. Hilla Becher was also interested in industrial forms from early on in her career, and began taking industrial photographs in the 1950s.

3 Hilla Becher, quoted by James Lingwood in Marc Freidus, James Lingwood and Rod Slemmons, eds, Typologies: Nine Contemporary Photographers, Palo Alto, CA, 1991, 17.

4 See Bertolt Brecht, ‘A reader for those who live in cities’, in John Willett and Ralph Manheim, eds, Bertolt Brecht Poems, 1913–1956, London, 1976, 131.

5 Walter Benjamin, ‘A short history of photography’, in One-Way Street, and Other Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter, London, 1979, 251.

6 Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, ‘Residual resemblance: three notes on the ends of portraiture’, in Melissa Feldman, ed., Face-Off, the Portrait in Recent Art, Philadelphia, PA, 1994, 62.

7 See Benjamin H. D., Buchloh, ‘Struth’s archive’, in Thomas Struth Photographs, Chicago, IL, 1990, 9.

8 Katl Ruhrberg and Thomas Grochowiak, eds, Anonyme Skulpturen, Formvergleiche Industrieller Bauten, Photos von Bernhard und Hilla Becher, Düsseldorf, 1969.

9 Since the early 1960s their preferred presentational mode has been the grid. The prints (each measuring 16 × 12 inches or smaller) are arranged into groups of nine or sixteen. Occasionally larger scale photographs are displayed beside each other, and the gallery space defines the groupings.

10 Hilla Becher, quoted in Lynda Morris, ed., Bernd und Hilla Becher, An Arts Council Exhibition, London, 1974, n.p.

11 Hilla Becher, quoted in Morris, Bernd und Hilla Becher, n.p.

12 Blake Stimson, The Pivot of the World. Photography and its Nation, Cambridge, MA, 2006, and Michael Fried, Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before, New Haven and London, 2008.

13 Stimson, The Pivot, 14.

14 Stimson, The Pivot, 22.

15 Stimson, The Pivot, 166.

16 Stimson, The Pivot, 166.

17 Blake Stimson, ‘The photographic comportment of the Bechers’, lecture given at Tate Modern, 2003, n.p.

18 Stimson, The Pivot, 143.

19 Stimson, The Pivot, 167.

20 Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, New York, 1979,19-20.

21 Stimson, The Pivot, 174.

22 See G. W. F. Hegel, Science of Logic, trans. A. V. Miller, New York, 1969.

23 See Robert B. Pippin, Hegel’s Idealism: The Satisfaction of Self-Consciousness, Cambridge and New York, 1989.

24 Fried, Why Photography Matters, 324.

25 Fried, Why Photography Matters, 326.

26 Fried, Why Photography Matters, 328.

27 Fried, Why Photography Matters, 329.

28 Fried does not explicitly use the term ‘aesthetics without aesthetics’ in his book, but he did do so in his lecture ‘To complete the world of things: on the Bechers’ typologies’, given at University College London, 1 December 2005.

29 Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, ed. Gretel Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor, London, 1997.

30 Strikingly, the Bechers are not alone in their rejection of ideology. Some of the most prominent German artists in this period have frequently discussed their rejection of ideology and its incompatibility with artistic practice. Most notable of these is Gerhard Richter, who has repeatedly claimed the importance of his practice being anti-ideological: ‘I have become involved with thinking and acting without the help of an ideology . . . Ideologies seduce and exploit uncertainty, legitimise war.’ Richter, quoted in Michael Danoff, ‘Heterogeneity’, Gerhard Richter’s Paintings, London, 1988, 9–10.

31 Thierry de Duve, ‘Bernd and Hilla Becher, or monumental photography’, in de Duve, Bernd und Hilla Becher: Basic Forms, New York, 1992, 21.

32 Martin Kolinsky and William E. Paterson, eds, Social and Political Movements in Western Europe, London, 1976, 78.

33 Frank Biess, ‘Survivors of totalitarianism: returning POWS and the reconstruction of masculine citizenship in West Germany, 19451955’, in Hanna Schissler, ed., The Miracle Years: A Cultural History of West Germany 1949–1968, Princeton, NJ and Oxford, 2001, 73.

34 Kolinsky and Paterson, Social and Political Movements, 75.

35 For example, the American social scientist David Riesman. See Robert G. Moeller, West Germany Under Construction: Politics, Society and Culture in the Adenauer Era, Ann Arbor, MI, 1997, 399.

36 Kolinsky and Paterson, Social and Political Movements, 75.

37 Richard Hinton Thomas and Keith Bullivant, eds, Literature in Upheaval: West German Writers and the Challenge of the 1960s, Manchester, 1974, 33.

38 Shelley Frisch, ‘The turning down of the Turning Point: the politics of non-reception of exile literature in the Adenauer era’, in Dieter Sevin, ed., Die Resonanz des Exils: Gelungene und Misslungene Rezeption Deutschsprachiger Exilautoren, Amsterdam, 1992, 208.

39 See Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 234.

40 See Espen Hammer, Adorno and the Political, London, 2005, 86.

41 See Slavoj Zizek’s discussion of Frederic Jameson’s non-utopia in Zizek, ‘Multiculturalism, or, the cultural logic of late capitalism’, New Left Review, 1, 225, September-October 1997, 28–51.

42 See Adorno and Max Horkheimer, The Dialectic of Enlightenment, ed. Gunzelin Schmid Noerr, trans. Edmund Jephcott, Stanford, CA, 2002.

43 Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 2.

44 See James Lingwood, ‘The music of the blast furnaces: Bernhard and Hilla Becher in conversation with James Lingwood’, in Susanne Lange, Bernd and Hilla Becher: Life and Work, trans. Jeremy Gaines, London, 2007, 194.

45 Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 3.

46 See Bernd and Hilla Becher, Fachwerkhäuser des Siegener Industriegebietes, Munich, 1977.

47 Peter Osborne, ‘Adorno and the metaphysics of modernism: the problem of a “postmodern” art’, in Andrew Benjamin, ed., The Problems of Modernity: Adorno and Benjamin, London, 1989, 24.

48 See Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge, London, 1972.

49 Adorno, Prisms, trans. Shierry Weber Nicholson and Samuel Weber, Cambridge, MA, 1983, 233.

50 Adorno, Prisms, 233.

51 Adorno, Prisms, 233.

52 Adorno, quoted by Osborne in Benjamin, Problems of Modernity, 31.

53 Frederic Jameson is particularly concerned with the ambiguous status of the category, and concludes that mimesis should be understood as the substitute for the traditional subject-object relationship. See Jameson, Late Marxism: Adorno, or, The Persistence of the Dialectic, London, 1990, 256. For a discussion of the role of mimesis in Adorno, see Isabelle Graw, ‘Adorno is among us’, trans. James Gussen, in Adorno: The Possibility of the Impossible, Berlin, 2003,13-28.

54 Tom Huhn ‘Introduction: thoughts beside themselves’, in Huhn, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Adorno, Cambridge, 2004, 5.

55 Huhn, Cambridge Companion, 7.

56 Hunh, Cambridge Companion, 5.

57 Huhn, Cambridge Companion, 7.

58 Osborne in Benjamin, Problems of Modernity, 32.

59 Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 329.

60 Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 42.

61 See Shierry Weber Nicholson, Exact Imagination, Cambridge, MA, 1997, 32.

62 Huhn, Cambridge Companion, 8.

63 Adorno, ‘Education after Auschwitz’, in Lydia Goehr, ed., Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords, New York, 2005,195.

64 Jameson, Late Marxism, 215.

65 See Adorno, ‘Gloss on personality’, in Goehr, Critical Models, 165.