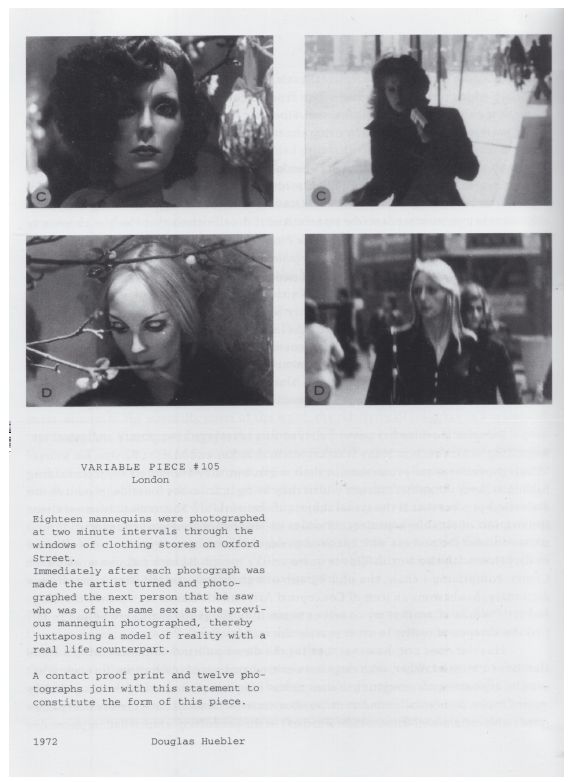

1 Douglas Huebler, Variable Piece # 105, London, 1972,1972. Photographic reproduction and printed text, dimensions variable. As printed in Origin and Destination: Alighiero E Boetti, Douglas Huebler, Brussels: Société des Exposition du Palais des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles, 1998. Photo: © 2009 Estate of Douglas Huebler/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

5

EXIT GHOST: DOUGLAS HUEBLER’S FACE VALUE

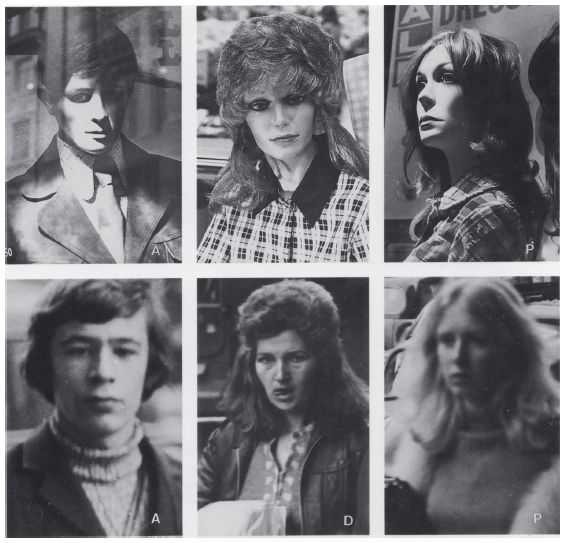

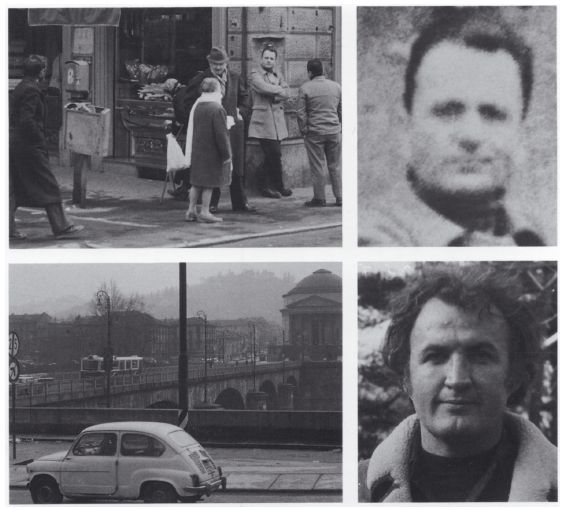

There is something more than a little ridiculous in the pairing of mannequins to people that Douglas Huebler presents us with in his 1972 Variable Piece #105, London, 1972 (plate 2). All the more so given that the text accompanying this work asks us to believe what, to me at least, seems frankly unbelievable: after each mannequin was photographed, it was matched with another shot taken of the first random person encountered of the same gender. As proof of this claim, Huebler includes his contact sheet as part of the work – an inclusion that, of course, proves absolutely nothing: twenty seconds, twenty hours, or twenty days could have lapsed between the sequence of photographs for all this tells us. But given the resemblance – I’m almost tempted to say ‘uncanny resemblance’, but I’ll get to that shortly – between most of the mannequins and their living counterparts, credibility as far as I am concerned is stretched well beyond the breaking point. Are we really supposed to believe that the shared appearance in the photographs of the woman and her dummy in the middle of the grid, where we see the same, slightly bizarre hairstyle repeated above and below, is sheer coincidence? Or, in another version of the work (see plate 1), claims for happenstance pure and simple are again cast in a dubious light when we see a coupling of blonde to blonde and brunette to brunette, each pair sharing more-or-less the same haircut and even facial features. Looking at these doubles, I doubt strongly that Huebler is really expecting us to take him at face value here.

Talking to a group of faculty and students in 1973 at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax, Canada, Huebler describes in some detail how he came to make Variable Piece #105, London, 1972:

For several years I’d been interested in the different styles of mannequins in store windows, and, like a lot of things I do, I think about those things but I don’t think very hard, and then one day sometime later it occurs to me, this is what I’ll do. And so, after a couple of years of being interested in those things, it occurred to me that I would make photographs of mannequins in London. I mean, I happened to be in London and it occurred to me there, that I would make photographs and then photograph the next person I saw of the same sex. So I would snap off from the store window and then turn and shoot the next male or female depending on what the mannequin had been – to put the two kinds of realities into juxtaposition like that without intending to prove anything. Again, that’s important to me. I’m not trying to prove anything. It’s kind of like setting the strategy and just doing that and seeing what I got.1

2 Douglas Huebler, Variable Piece # 105, London, 1972,1972. Photographic reproduction and printed text, dimensions variable. As printed in Douglas Huebler ‘Variable’, etc., Limoges: F.RA.C. Limousin, 1993. Photo: © 2009 Estate of Douglas Huebler/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

At first blush this appears to put to rest any doubts about the veracity of Huebler’s system. Plain as day, he seems to tell us exactly how went about conceiving, establishing, and following his system, which he did, apparently, to the letter: ‘it’s kind of like setting the strategy and just doing that and seeing what I got’. But what, exactly, is Huebler’s ‘strategy’? The implication is that he works in a manner akin to Sol LeWitt’s systems-based view of conceptual art, whereby ‘all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair’.2 Does Huebler therefore simply propose and set a system in motion, following it through to its clockwork conclusion in order to see what happens? Or could his ‘strategy’ be a little more sly perhaps – a little more strategically cunning or canny in precisely the manner suggested by his choice of word, and in a way that the more obvious and mechanical connotations of the term ‘system’ do not carry? Could the photographs, in other words, function in such a way that they do not simply reiterate and support the linguistic statement, providing visual evidence, or proof, as to the work’s proper execution, but on the contrary put the entire work, statement included, under pressure in ways that throw all claims to fidelity into question? Is it the system itself that is being tested, or the limits of our faith in that system?

Most jarring in Huebler’s otherwise matter-of-fact description of Variable Piece #105, London, 1972, however, is the way he twice stresses that the photographs are not intended as proof, despite the obvious fact that the whole conceit of the contact sheet – or ‘contact proof print’ as it is significantly termed in the statement – is to provide exactly that: proof that the statement is good to its word (‘without intending to prove anything. Again, that’s important to me. I’m not trying to prove anything’). Similar candour regarding the known, even deliberate failure of photographic documentation to function as proof crops up time and again in interviews with Huebler: ‘In the same sense that I don’t care about specific appearance, I don’t really care about precise or exhaustive documentation. The documents prove nothing.’3 Further troubling to any viable claim the work might have to truth is that Huebler also casts doubt on the statement itself. Thus, shortly before his description of Variable Piece #105, London, 1972, Huebler slips in this slightly too offhand comment: ‘You know, again, I can say anything I want in these statements. People can believe it or not.’4 It’s almost impossible to imagine Huebler saying this without being aware of how it recasts the performative function of the linguistic statements in his work from doing to saying. Maybe the statement is true; maybe it’s not. Maybe these really were the first random people he turned his camera on after the mannequins, incredible though it seems, or maybe, given Heubler’s admission (‘I can say anything I want in these statements’) he is just saying he did. In the end the decision is ours to believe. Or not.

Huebler’s double assertion/negation of the system crops up again in a 1969 interview with Patricia Norvell. In it, Huebler first underscores the importance of the system to his work: ‘I set up a system, and the system can catch a part of what is happening in the world – what’s going on in the world – an appearance in the world, and suspend that appearance itself from being important.... The work is about the system.’5 The system, in other words, ‘suspends’ or drains away entirely the conventional function of the photograph – its ability to capture ‘appearance in the world’. As the interview continues, however, it becomes evident to Norvell that, in almost the same breath, Huebler will assert and negate the very system he has just been describing. Significantly, it is precisely the question of the interval period between photographs that prompts Norvell to question the status of Huebler’s system:

Douglas Huebler: Trying to show the system, or the idea, the things that you’ve set up as the structure within which you will work, is what the art’s about.

Patricia Norvell: But then you say it doesn’t matter whether the pictures were taken every minute or every five days.

Douglas Huebler: That’s right.

Patricia Norvell: So then you’re destroying your system, or you’re ignoring it?

Douglas Huebler: Right, right, right. That’s right because, as I said, these systems do not prove anything either. They’re dumbbell systems… 6

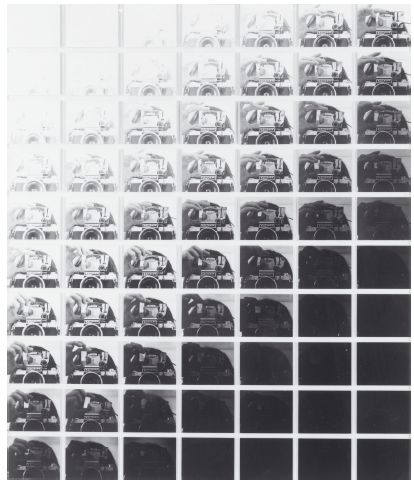

3 John Hilliard, Camera Recording its Own Condition (7 Apertures, 10 Speeds, 2 Mirrors), 1971. Photographs on card on perspex, 2162 × 1832 mm. London: Tate Modern. Photo: © Tate, London 2009/Art Resource, New York.

If Huebler throws adherence to his own system into doubt, as he seems so intent to do, this undermining of his own ground rules is consistent with one side of what I’ve elsewhere argued to be to a more general strategy in Huebler’s work of the 1970s.7 For during this period, I’ve claimed, Huebler sets out to undermine two very different forms of photographic practice: on the one hand, the work of systems-based photographers such as Bernd and Hilla Becher, John Hilliard (plate 3), Mel Bochner, Edward Ruscha, or indeed Huebler’s own early conceptual work of the late 1960s; and on the other a form of portraiture, often taken to expressive excess, in the mode of New York School photographers such as Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Bruce Davidson, and Lisette Model (plate 4). Significantly, from 1970 on, Huebler sets out to negate both these forms of photography in the very structure and subject of his work. Accordingly, he not only uses systems that more often than not do not work, introduce scepticism, or otherwise break down by design, but he also engages in a near-exclusive use of photographic portraiture. Indeed, the undoing of both systems-based photography and photographic portraiture through their own means is precisely what we see in Variable Piece #105, London, 1972.

Thus, according to the text of this work, the photographs are taken according to the constraints of a pre-established system: eighteen mannequins are photographed at two minute intervals on Oxford Street in London. After each photograph is taken of a mannequin, another is then taken of the first person walking by of the same gender. Mannequins and people are then paired and, as seen in the final presentation, labelled from A to R. But in so clearly matching the appearance of person to mannequin – or, indeed, by presenting us with not one, but two sets of photographs marked ‘D’ – Huebler seems to suggest, if not actually flaunt, the contravening of his own rules, introducing a deal-breaking scepticism into the very system that he himself put in place. Far from laying to rest any doubts about his fidelity to the system, the appeal to patently bogus evidence in the form of the contact sheet only increases our distrust, as indeed I think it is intended to do.

4 Lisette Model, Woman with Veil, San Francisco, 1949. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada (Gift of Dorothy Meigs Eidlitz, St Andrews, New Brunswick, 1968). Photo:© National Gallery of Canada. Used by permission of The Lisette Model Foundation, Inc. (1983).

So if Huebler pulls at the threads of systems-based photography in Variable Piece # 105, London, 1972, in what way do these photographs also unravel the expressivity of New York School photographic portraiture a la Arbus? The most obvious answer is that the system itself is designed precisely to frustrate the kind of authorial nuance one would expect in an Arbus or Davidson photograph. The sheer speed at which the work must be executed – the system requires that Huebler take thirty-six photographs in as many minutes – necessarily hinders the photographer’s ability to introduce any aesthetic finesse into the final product. Likewise the decision to shoot these particular people is not based on how compelling or photogenic a face they might have – ‘a face that can hold a wall’, as Avedon put it8 – but rather the pure arbitrariness of whoever walks by at that particular moment. Or so, at least, we are told. But if Huebler is indeed cheating – and to my eye he is at pains to show us that he is – then none of these constraints would apply. Huebler cannot, in other words, negate systems-based photography while at the same time appealing to it as a means to hollow out the aesthetic and expressive content of photographic portraiture.

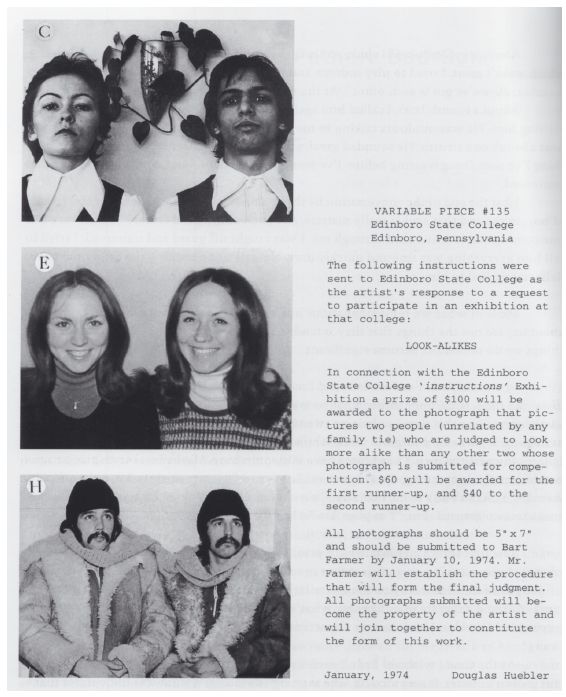

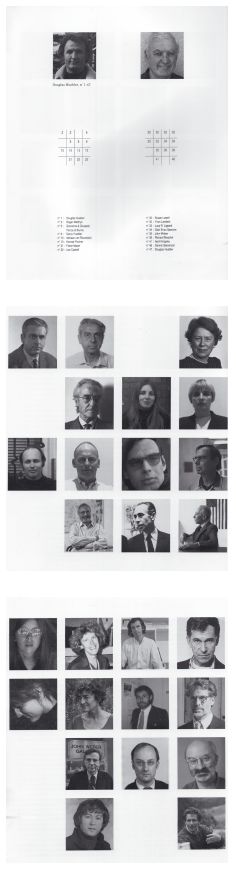

In place of a system, then, I would argue that Huebler uses another strategy to flatten the subjective resonance of his faces. And this strategy is not only manifest in the breaking of rules that seems to me on open display in Variable Piece # 105, London, 1972, it is wholly dependent on it. For in his matching of mannequins, not with random passersby, but with actual look-alikes, one of the ways in which Huebler winks and nods to let us know that he is not being altogether true to his statement is the fact that look-alikes recur again and again as an explicit thematic concern of his work. We see this, for example, in Variable Piece # 135, Edinboro State College, Edinboro, Pennsylvania, 1974 (plate 5), where Huebler awarded first, second, and third cash prizes to look-alike contestants who were judged to bear the greatest mutual resemblance. Again, each pairing appears slightly more absurd than the next, as we move across a range of similarities – from the not very, to the almost uncanny (I emphasize almost) – each mirroring the other in facial expression and/or, just to drive the point home, clothing. The double appears again – Huebler’s own this time – in Location Piece # 17, Turin, Italy, 1973 (plate 6). Accidentally taken by Huebler while in Turin, in this picture we see a grainy, photographic enlargement of a man who, according to Huebler’s statement, bears ‘a strong resemblance to the artist… at least more so than almost everyone else in the world’. If Huebler claims to have stumbled upon his long-lost double here, he finds an even more proximate doppelganger in Variable Piece # 44, Global, 1971, this time in the form of a past self (plate 7). In the final version of this work, forty-seven participants – Huebler included – provided two photographic images of their face, one taken in 1971, the other in 1981. Absences appear where individuals died or could not be contacted. For those with double portraits we see individuals doubled as simultaneously same and different, alike and unlike, cast in a relation of comparative difference.9

Knowing that Huebler was directly concerned with images of the double, it seems even more unlikely that the physical similarities between mannequins and people in Variable Piece #105, London, 1972 are a fluke. But more than just giving the lie to Huebler’s system, these particular doubles reflect Huebler’s larger strategy to drain the photographic portrait of its expressive and subjective resonance. And they do so, significantly, in tandem with both the work’s claim to coincidence (however dubious) – that this particular person just happened to walk by at this particular moment – and the use of mannequins. For even if one were to accept what the text tells us, rejecting my view that Huebler deliberately paired like with like, we would still have the effect of almost uncanny coincidence – though again I stress the almost. But if the claim to coincidence is too much to swallow, we are still left with doubles and mannequins.

5 Douglas Huebler, Variable Piece # 135, Edinboro State College, Edinboro, Pennsylvania, 1974, 1974. Photographic reproduction and text, dimensions variable. As printed in Origin and Destination: Alighiero E Boetti, Douglas Huebler, Brussels: Société des Exposition du Palais des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles, 1998. Photo: © 2009 Estate of Douglas Huebler/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

6 Detail of Douglas Huebler, Location Piece # 17, Turin, Italy, 1973,1973. Photographic reproduction and text, dimensions variable, 1973. As printed in Douglas Huebler ‘Variable’, etc., Limoges: F.RA.C. Limousin, 1993. Photo: © 2009 Estate of Douglas Huebler/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

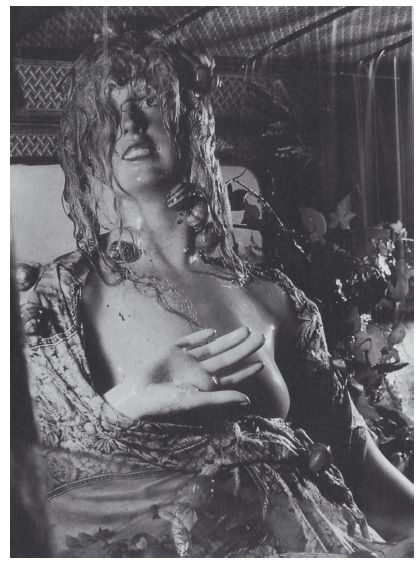

So either way you cut it, what we end up with – astounding coincidences, doubles and mannequins – are the once privileged sites of surrealism’s efforts to tap into ‘the Marvellous’. Indeed, photographs of mannequins, almost de facto evoke (how can they not?) the precedent of surrealist photography (plate 8). That the surrealists were besotted with mannequins as ‘a symbol apt at stirring human sensibility’, as André Breton famously put it in the 1924 Surrealist Manifesto, is, of course, conventional knowledge by this point. Less well known is that, for Breton at least, the ability of mannequins or mannequin-like objects to stir this human sensibility is historically constituted. As Breton states: ‘The Marvelous is not the same in every period of history: it partakes in some obscure way of a sort of general revelation only the fragments of which come down to us.’10

If Breton leaves this suggestion undeveloped – that the objects of the Marvellous are subject to the conditions of history – Fredric Jameson picks up the ball and runs with it. Thus, according to Jameson, a significant historical shift has occurred since the heyday of surrealism, such that the movement’s once venerated objects no longer carry, nor indeed to any real degree are they capable of carrying, the charge of uncanny frisson. But if the battery of the uncanny has gone flat, so to speak, it is not simply because these objects have degenerated into cliché (although presumably that doesn’t help). Rather, Jameson argues that the surrealist delight in the face of these objects – a delight sparked as animate and inanimate co-mingle – is emblematic of, and indeed possible only in relation to, the broader conditions of mass production prior to World War Two. For at this particular moment in the twentieth century, in advance of full-blown monopoly capitalism, commodity objects continued to bear a trace, however repressed, of their human manufacturing. As Jameson puts it: ‘what prepares these objects to receive the investment of psychic energy characteristic of their use by Surrealism is precisely the half- sketched, unaffected mark of human labor, of the human gesture, on them.’11 Objects at this time thus appear to have been assembled by actual living workers, rather than machines. We see this – or more correctly, sense this – for instance, in the visible welds or the sundry screws and bolts of pre-war objects that have been inserted and tightened by human hands, in sharp contrast to the microelectronics and the plethora of brightly coloured, injection-moulded plastic gee-gaws that currently flood the aisles of our stores. Human sensibility returns as the repressed, haunting the forms of early and mid-twentieth-century commodity objects. Tom McDonough describes surrealism’s interest in these ghost-like traces of human production within the industrial object in this way:

7 Douglas Huebler, Variable Piece # 44, Global, 1971, 1971. Photographs and printed text on board, 457 × 613 mm. London: Tate Modern. As printed in Douglas Huebler ‘Variable’, etc., Limoges: F.R.A.C. Limousin, 1993. Photo: r 2009 Estate of Douglas Huebler/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

8 Raoul Ubac, Dali’s Rainy Taxi, 1938, detail of Salvador Dali, Rainy Taxi, from the International Surrealist Exhibition, Galerie de Beaux-Arts, Paris, 1938. Gelatin silver print. Photo: © 2009 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

The critical force of the spectral was linked ultimately to the project of rational enlightenment. The world of commodities might present itself as a phantasmagoria, alternately terrifying and seductive, but the mechanisms of such false appearance and illusion could be revealed for what they were; what Marx called the ‘religion of the everyday’ could be shown to be the product of mere human labor and the social relations between producers. Even the Surrealist interest in the uncanny was less a means of reenchanting the world than of figuring the alienated labor that lay behind the false appearance of the commodity.12

The same traces of a repressed human sensibility are also found in the distribution of these objects, which during the surrealist era depended largely on small shopkeepers who distributed goods produced by equally small workshops to an established and known clientele. Face-to-face interactions, as T.J. Clark describes them, continued to serve the entwined social and business interests of Parisian quartier life; long after the city’s initial wave of modernization, such that ‘business and sociability were bound together’.13

Along the same lines, it is significant that the marche aux puce, with all its complex back-and-forth negotiations of price, was the privileged site of discovery for the surrealists. It is this spectral presence – this stirring of human sensibility in the otherwise lifeless industrial object – that is brought to the fore with surrealism’s fascination with mannequins, waxworks, automatons, and the like. ‘The mannequin’, Jameson writes, thus serves as a: ‘veritable emblem of the sensibility of a whole age, [the] supreme token of the surrealist transformation of life – in which the human body itself comes before us as a product, where the nagging awareness of another presence… the terror of the blue gaze that meets us from the doll’s eyes… figure emblematically the central discovery of Surrealism of the properties of the objects that surround it.’14

Along similar lines, Hal Foster argues that surrealism’s interest in outmoded objects and sites of commodity exchange – he takes Breton’s trouvaille (lucky find) of a spoon with a boot carved into its handle as the former, and where he found it, the flea market, as the latter – are part and parcel of the historical nature of the uncanny. As Foster writes:

The spoon is thus an instance of the first order of the surrealist outmoded: a token of a precapitalist relation that commodity exchange has displaced or submerged. Here its recovery might spark a brief illumination of a past productive mode, social formation, and structure of feeling – an uncanny repressed moment of direct manufacture, simple barter, and personal use.15

To the still perceptible trace of the commodity’s human origins and distribution during the pre-war period, Jameson contrasts the flat, hollow, lifeless objects of pop – Warhol’s soup cans, for instance, or Wesselmann’s still lives. But a much better comparison, I think, is the more direct example of Huebler’s Variable Piece # 105, London, 1972. For in the utterly matter-of-fact faces of Huebler’s mannequins and look-alikes, one would be hard pressed to find even the faintest flutter of Breton’s Marvellous.

So what does all of this have to do with what Benjamin Buchloh has described as ‘the spectacular and grotesque distortions of subjectivity in the New York school [of photographic portraiture]’, which, you will recall, I am claiming to be the target of Huebler’s turn to photographic portraiture in the 1970s? Before I get to Arbus and her contemporaries, however, I want to look first at another, nonMarxist and much more melancholic argument that our contemporary world of images has become flat and lifeless, this time in direct relation to photography. This occurs in the concluding pages of Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida. Towards the very end of the book, he makes a veiled but unmistakable reference to E. T. A. Hoffmann’s famous story ‘The Sand-Man’. Barthes has been trying to describe the ‘madness’ and ‘hallucinatory’ effect of photography, when suddenly we find this:

The same evening of a day I had again been looking at photographs of my mother, I went to see Fellini’s Casanova with some friends; I was sad, the film exasperated me; but when Casanova began dancing with the young automaton, my eyes were touched with a kind of acute and delicious pain, as if I were suddenly experiencing the effects of a strange drug; each detail, which I was seeing so exactly, savoring, so to speak, every last part of it.... At which moment I could not help but thinking of Photography.… Was I not, in fact, in love with the Fellini’s automaton? Is one not in love with certain photographs?16

The reference is clear: for not only does the protagonist of Hoffman’s story – the young Nathaniel – also, like Barthes, fall in love with an automaton, he succumbs in turn to hallucinations and madness – the very attributes that Barthes sees as at the heart of his love of photography.

Barthes’ allusion to the ‘Sand-Man’ is, of course, a reference within a reference; it is not Hoffmann’s story per se that interests Barthes, but Freud’s famous reading of it in an essay, ‘The Uncanny’. More than any other text, it was this essay that brought automatons, waxworks, mannequins, and identical twins to theoretical life. But as with automatons, Barthes claims, so too with photographs – or at least the photographs that he loves, the photographs that touch and wound him. And in this claim for photography’s uncanniness, Barthes is by no means alone. Indeed, if the uncanny, as a theoretical concept, has become more than a little tired of late – one can barely speak the term these days without the blush of academic embarrassment – a significant amount of photographic criticism has seemed immune from this fatigue. Thus, for many writers on photography, the medium is haunted by an inherent uncanniness. ‘There is something uncanny in every photograph’,17 Eduardo Cadava and Paola Cortes- Rocca state unequivocally, while for Carol Armstrong, ‘the disquiet resident in photography, is nothing else but the photographic uncanny, buried in the homely, everyday, banal details of every-photograph.’18 Or again, as George Baker puts it, there exists a ‘primary uncanniness that belongs to the photographic as such’.19

Alas, Barthes argues mournfully, the photographic uncanny that he associates with the dancing automaton is definitively not present ‘as such’ nor ‘in every photograph’. Quite the contrary, in fact, for it is precisely this madness that is all but lost to us. ‘Society’, Barthes writes in the concluding section of his book (and by this it is clear he means contemporary society), ‘is concerned to tame the photograph, to temper the madness which keeps threatening to explode in the face of whoever looks at it.’ As Barthes states, the photograph is tamed when it becomes generalized and banal (these are his terms). This, he claims, is the ‘great mutation’ – a mutation, or what he also calls a reversal, such that we no longer see our desires projected onto the photograph, but the opposite: our desire now originates with the images. As Barthes puts it:

What characterizes the so-called advanced societies is that they today consume images and no longer, like those of the past, beliefs; they are therefore… more ‘false’ (less authentic)… as if the universal image were producing a world without difference, from which can rise, here and there, only the cries of anachronisms, marginalisms, and individualisms: let us abolish the images, let us save desire (desire without mediation).

So writes Barthes on the concluding page of Camera Lucida, with a Debordian tinge of despair at the colonization of our desires by the image.

If Barthes strikes a more melancholic, despairing note than Jameson’s Marxism would allow, lamenting that the once-hallucinatory power of photographs has become generalized and banal (and like Jameson, it is hard not to suspect he also has Warhol in the back of his mind here), both critics nonetheless come to the same conclusion. Thus even though Jameson doesn’t address the subject of photography directly, it is clear that he, like Barthes, would no more attribute an innate uncanniness to the medium, outside the conditions of history, than he would to mannequins. And with this Huebler is in total agreement. For the claim to photography’s constitutive uncanniness is exactly what Huebler’s photographic portraits render null. And what is more, they do so precisely in the context of a prominent assertion of photography’s uncanniness, not by critics so much as by photographers. Huebler’s mannequins should therefore be seen in stark opposition to Arbus’s, Model’s, or Helen Levitt’s coupling of persons with mannequins, or Arbus’s photographs of waxworks, that favoured image of the ‘marvellous’, and, of course, her doubles. Confronted with a widespread draining away of photographic affect, Arbus appears to respond by ratcheting up the subjective intensity of her photographs through an appeal to these slightly tired sites of the Marvellous. And it is precisely this intensity that we see Huebler, not just tamping back down, but hallowing out altogether. Carol Armstrong claims that Arbus’s image of identical twins ‘surely signifies “Diane Arbus” as much as anything else’, and who could claim otherwise?20 Certainly not Huebler, I think, who presents us with his twins as a kind of riposte.

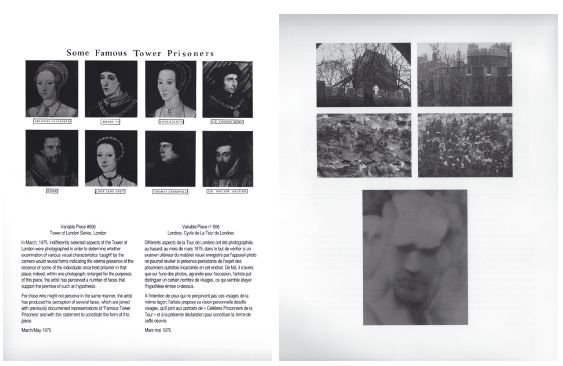

9 Douglas Huebler, Variable Piece # 506, Tower of London Series, London, 1975,1975. Photographic reproduction and printed text, dimensions variable. As printed in Douglas Huebler ‘Variable’, etc., Limoges: F.RA.C. Limousin, 1993. Photo: © 2009 Estate of Douglas Huebler/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

I exit here not with uncanny doubling, or the manifest lack thereof, but with another (un)uncanny image: the image of a ghost as it appears in Huebler’s Variable Piece # 506, Tower of London Series, London, 1975 (plate 9). ‘Many people experience the feeling [of the uncanny] in the highest degree in relation to death and dead bodies, to the return of the dead, and to spirits and ghosts.’21 If there is a grain of truth in this statement of Freud’s, one would be hard pressed to find even the faintest trace of it in Variable Piece # 506, Tower of London Series, London, 1975.22 In this work, Huebler presents us with various close-range photographs of the walls of the Tower of London. From these he in turn made a series of enlargements that, as he writes in his statement, ‘reveal forms indicating the eternal presence of the essence of some of the individuals once held prisoner in that place’. In the photographic details of the wall, Huebler looks for – and finds – a variety of malformed shapes that can be seen, with a generous eye, to resemble human faces. These faces he then couples with portraits of historical ‘Famous Tower Figures’. As much as Arbus’s twins have come to signify ‘Diane Arbus’, the faces of these ghosts, for me, have come to signify ‘Douglas Huebler’ – or at least that side of his practice that engages with the status of photographic portraiture. For in these empty faces, we catch a glimpse, not of a ghost, but of the empty remains of the once spectral presence of photography.

Notes

Particular thanks to Diarmuid Costello, Margaret Iversen, and Jennie King for all of their help and feedback. Grateful acknowledgement also to Darcy Huebler for all of her help and permission for the use of images.

1 Douglas Huebler, ‘Douglas Huebler’, in Peggy Gale, ed., Artists Talk: 1969–1977, Halifax, 2004, 227.

2 Sol LeWitt, ‘Paragraphs on conceptual art’, Artforum, 10, June 1967, 79; reprinted in Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson, eds, Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, Cambridge, MA, 2000,12.

3 Douglas Huebler, in Arthur R. Rose [pseudo.], ‘Four interviews with Barry, Huebler, Kosuth, Weiner’, Arts Magazine, 4, February, 1969; Reprinted in Gregory Battcock, ed., Idea Art: A Critical Anthology, New York, 1973, 144.

4 Huebler, Artists Talk, 224.

5 Douglas Huebler, Interview with Patricia Norvell, 25 July 1969, in Alexander Alberro and Patricia Norvell, eds. Recording Conceptual Art, Berkeley, CA, 2001, 147.

6 Huebler, Interview with Patricia Norvell, 148.

7 See my, ‘Game face: Douglas Huebler and the voiding of photographic portraiture’, Art Journal, 4, Winter 2007, 52–69.

8 Laura Wilson, Avedon at Work in the American West, Austin, TX, 2003 102; quoted in Julian Stallab- rass, ‘What’s in a face? Blankness and significance in contemporary art photography’, October, 122, 2007, 78–9.

9 Again note how Huebler appears to violate his own rules, using photographs that seem fairly obviously to have a more than ten-year age difference. The early photo is also used in Variable Piece # 17, a work from 1973, which calls into question whether or not it was taken in 1971 as claimed.

10 André Breton, ‘Manifesto of surrealism’ (1924), Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane, Anne Arbor, MI, 1969, 16.

11 Frederic Jameson, Marxism and Form, Princeton, NJ, 1971,104.

12 Tom McDonough, The Beautiful Language of My Century: Reinventing the Language of Contestation in Postwar France, 1945–1968, Cambridge, MA, 2007, 184–5.

13 T. J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers, Princeton, NJ, 1984, 52.

14 Jameson, Marxism and Form, 104–5.

15 Hal Foster, Compulsive Beauty, Cambridge, MA, 1993, 161.

16 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard, New York, 1981, 115–16.

17 Eduardo Cadava and Paola Cortés-Rocca, ‘Notes on love and photography’, October, 116, Spring 2006, 16.

18 Carol Armstrong, ‘From Clementina to Kasebier: the photographic attainment of the “Lady Amateur’’’, October, 91, Winter 2000,106.

19 George Baker, ‘Photography between narrativity and stasis: August Sander, degeneration, and the decay of the portrait’, October, 76, Spring 1996, 101.

20 Carol Armstrong, ‘Biology, destiny, photography: difference according to Diane Arbus’, October, 66, Fall 1993, 37.

21 Sigmund Freud, ‘The uncanny’, from The Penguin Freud Library, Vol. 14: Art and Literature, trans. James Strachey, London, 1985, 364.

22 Tom McDonough makes a similar claim for Pierre Huyghe’s and Philipe Parreno’s No Ghost Just a Shell to the one I am making for Huebler’s work. As McDonough argues, Huyghe and Parreno signal ‘the demise of one of the great figures of modern oppositional culture – the obsession with specters and the phantasmogoric, the untimely and the unhomely, activated by the Surrealists some eighty years ago as the return of what bourgeois society resolutely had repressed. It is the uncanny itself whose critical force seems to have become exhausted.’ McDonough, The Beautiful Language of My Century, 181.