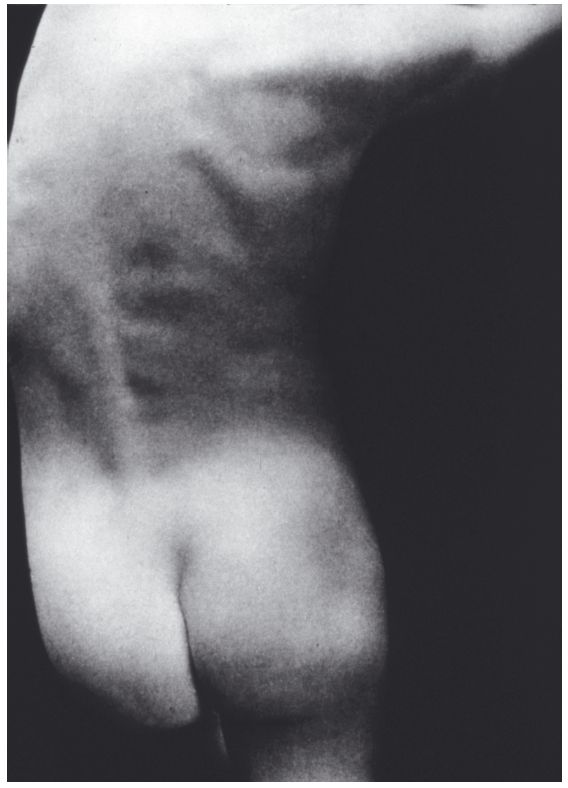

1 Sherrie Levine, After Edward Weston (# 5), 1980. Black and white photograph, 25.4 × 20.3 cm. Photo: © Sherrie Levine. Courtesy of the Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

8

THOMAS DEMAND, JEFF WALL AND SHERRIE LEVINE: DEFORMING ‘PICTURES’

What are we to make of the return of the ‘picture’ in photography after conceptual art? Originally associated with the brand of ‘critical’ or ‘oppositional’ postmodernism first identified in Douglas Crimp’s catalogue essay, ‘Pictures’, of 1977, the ‘picture’ has more recently been revived, on the one hand, in practice, in the large-scale, so-called ‘pictorialist’ photography practised by Andreas Gursky or Thomas Demand, and on the other, in photography theory, in a number of essays published by Jeff Wall.1 Whilst the contemporary return to the picture might at first sight seem far removed from Crimp’s use of the term, in fact, the two manifestations are connected by the rather unexpected importance given by each to the work of Sherrie Levine. Levine’s work can thus be seen to present a problem-case for the ‘picture’. To Crimp and other theorists of the earlier moment such as Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Levine’s photographic appropriations of original works by older, male, modernist photographers such as Edward Weston seemed exemplary of a postmodern attack on such foundation-stones of modernist aesthetics as originality, authenticity and individual creativity.2 Yet in an essay published in 2003, Jeff Wall performed his own act of appropriation, lifting Levine’s work over to his side of the boundary that Solomon-Godeau had drawn, between ‘art photography’ and art that, (like Levine’s) only uses photography.3 Wall wrote that he viewed Levine’s work as saying, ‘study the masters’ – in other words, as implying not a critique of authorship, as Crimp and Solomon-Godeau had it, but instead, obedience to authority, and a reinscription of it.4

Whilst Wall’s is a surprising and counter-intuitive reading of Levine’s photographs, nevertheless, it strikes me as useful for suggesting we attend to the specific force at work within her imitation of the ‘masters’. Viewed with Wall’s comments in mind, her work might recall Gilles Deleuze’s account of ‘force’, as illustrated in his account of the scream, which deforms the body even as it enacts obedience in response to compulsion.5 In this light, the twist of the boy’s body in Levine’s photographs After Edward Weston (1980) might become newly salient (plate 1). Even the ‘wince’ on the face of the woman (Carrie Mae Burroughs) in Levine’s After Walker Evans (1981) could be seen as taking on this sense of bodily twist which, in Deleuze’s account, marks the deforming impact of obedience, or ‘force’.

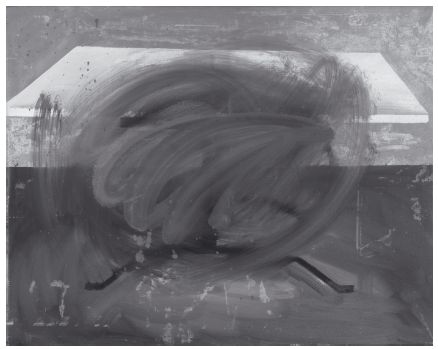

2 Gerhard Richter, Tisch (Table), 1962. Oil on canvas, 90.17 × 113.03 cm. Private Collection. Photo: © Gerhard Richter/Ben Blackwell. Courtesy of the artist and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

This reading would help refine our sense of what criticality Levine’s turn to the picture might be understood to possess, so that we understand it not on an avant-gardist model of oppositional critique, but instead as a more bodily resistance. This would help us then to understand how Levine could be important to both Wall’s account, on the one hand, and Crimp’s and Solomon-Godeau’s, on the other. ‘Resistance’ here would look identical with obedience – both being manifest in a single convulsion making visible that ‘force’ which speaks through or takes shape in the body’s borrowed material. However, whilst Deleuze found a source of optimism in this account, I shall remain ambivalent about the prospects of such a model of bodily ‘resistance’ as any kind of replacement for older avantgarde models of a progressive politics. Instead, I shall limit myself here to noting merely the diagnostic usefulness of Deleuze’s account of’force’ as productive of a particular kind of imagistic deformation. I want to suggest it is something of this sort that is at the root of the return of the ‘picture’ in photography after conceptual art. To step ahead of myself a little, I shall suggest that what we are given in the work of these ‘new pictorialists’ is a sense of the picture as a force of deformation of the figure and of space.

The usefulness of Wall’s essay for the present, then, lies in pointing out that Sherrie Levine should be considered at least as important a parent to the new pictorialism as Wall himself is usually thought to be. The next task is to become more precise about what this genealogy means for specific artists, and then to begin to differentiate amongst the several notably different artists often grouped together as post-Bechers photographers. For the purposes of this chapter, I propose to focus on Thomas Demand, whose work may be seen to link most strongly to that of Sherrie Levine, since the work of both involves appropriation. What are we to make of the double root I have proposed – Wall and Levine, the modernist and the postmodernist – as the basis of his practice and production?

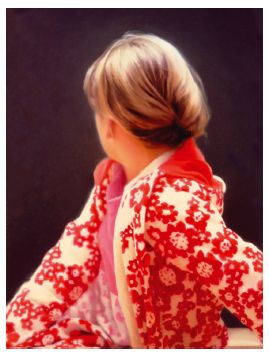

3 Gerhard Richter, Betty, 1988. Oil on canvas, 102.2 × 72.4 cm. Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum (funds given by Mr and Mrs R. Crosby Kemper Jr through the Crosby Kemper Foundations, The Arthur and Helen Baer Charitable Foundation, Mr and Mrs Van-Lear Black III, Anabeth Calkins and John Weil, Mr and Mrs Gary Wolff, the Honourable and Mrs Thomas F. Eagleton; Museum Purchase, Dr and Mrs Harold J Joseph, and Mrs Edward Mallinckrodt, by exchange). Photo: © Gerhard Richter. Courtesy of the artist and Saint Louis Art Museum.

Jeff Wall’s ‘first picture’, Destroyed Room of 1978, is entered as number 1 in his catalogue raisonné and described by the artist as the work from which he dates his mature production, although it is not the first he made.6 In this respect, Destroyed Room is comparable to Gerhard Richter’s Table of 1962 (plate 2), which is likewise considered by Richter’s commentators to be his ‘first picture’ in a psychological rather than a strictly historical sense, because it articulates for the first time the knot at the core of his artistic production.7 Table itself does a good job of picturing this: the gestural scrawl in the middle of the canvas, over the photo-realistic painting of a table, pits the marks of ‘abstract’ painting against the marks of representational painting, both of them, however, invalidated and cancelling each other out. This is the central ‘knot’ that would become the ‘braid’ or twist in even such a perfectly accomplished painting as Betty of 1988 (plate 3), in which photography and painting are centrally wound together, equally perfectly obliterating or ‘wiping’ the central focus of the figure that would be the girl’s face. The conundrum of painting’s destruction by photography is figured here in that what ruins the portrait is the seeming photographic happenstance, artfully confected in paint, that the girl has just turned her face away. Looking at Table and Betty together, the later painting seems like a repeat performance of Richter’s ‘first’, in the way in which the scrawl of the knot gets played out and displaced both in Betty’s serpentine pose and in the twist of her chignon. The result of photography’s intervention, pictured here in paint, is a kind of deformation of the figure, a central twist or braid.

I see Destroyed Room as performing the same sort of job in relation to Wall’s oeuvre that Table does for Richter’s. In Wall’s case, the job his picture does is to make plain that his project will be to lay bare the structure of pictorial composition. In Destroyed Room the knife-slashed mattress becomes the figure for something like the body of painting, embodying the picture that Wall will excavate and expose. As is well known, and as Wall has himself suggested, the central lozenge references the bed in Delacroix’s Death of Sardanapolous (1827–28), the raft in Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819), and the female mannequin in Duchamp’s Etant donnés (1944–66).

It is this last work in particular which enables the reading of the mattress as a stand-in for the body of the picture that Wall rends and turns out – a carcass he exposes. Indeed, it is interesting how much and how often Wall figures the picture on this model, as a body to which some violence has been done, producing remains on which his own work feeds. This is, surely, the insider’s joke (and we might pause to wonder if there is any other kind of joke in Wall than an ‘insider’s’ joke) in Vampire’s Picnic (1991); it is as though Wall were, throughout his practice, playing vampire at the feast of past paintings. After all, pictorial composition is so often figured as ‘disjecta membra’ in his work. The phrase seems apt for describing the peculiar appearance of disjointed fragments of pictorial composition in The Storyteller (1986), for example, which includes on the far lower left the group of figures from Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863). Elsewhere in the picture we see undigested ‘gobbets’ of Seurat’s Une Baiganade, Asniéres (1883–84) in the poses of the two figures left of centre. These are so unintegrated into the picture they look like waste, stray morsels of flesh strewn alongside the motorway overpass which stands in for Seurat’s river, seeming like a giant intestinal tube.

Support for conceiving of the picture-space as bodily in these terms comes from Roland Barthes, who points out that a bodily conception of pictorial composition is embedded within classical French picture-theory. Barthes quotes the following entire passage from Diderot’s essay ‘Composition’:

A well-composed picture [tableau] is a whole contained under a single point of view, in which the parts work together to one end and form by their mutual correspondence a unity as real as that of the members of the body of an animal; so that a piece of painting made up of a large number of figures thrown at random onto the canvas, with neither proportion, intelligence nor unity no more deserves to be called a true composition than scattered studies of legs, nose and eyes on the same cartoon deserve to be called a portrait or even a human figure.8

As Barthes points out in his own voice, the successful figural composition then bears a load which can only be described as fetishistic: ‘Thus is the body expressly introduced into the idea of the tableau, but it is the whole body. ... [T]he organs, grouped together and as though held in cohesion by the magnetic power of the segmentation, function in the name of a transcendence, that of the figure, which receives the full fetishistic load and becomes the sublime substitute of meaning: it is this meaning that is fetishized.’9 This bodily conception of composition is an idea which is echoed by Wall, who argues that the ‘painted body’ is ‘the central term of the classical concept of the picture’.10

What especially interests me is Barthes’ parenthetical remark in this essay. ‘Doubtless’, Barthes writes,

there would be no difficulty in finding in post-Brechtian theatre and post-Eisensteinian cinema mises-en-scene marked by the dispersion of the tableau, the pulling to pieces of the ‘composition’, the setting in movement of the ‘partial’ organs of the human figure, in short the holding in check of the metaphysical meaning of the work – but then also of its political meaning; or, at least, the carrying over of this meaning towards another politics.11

It is precisely this kind of disarrangement of parts that we witness, I think, in Wall’s (and, I shall argue, in Demand’s) pictures. An illustration of this is to be found in Diagonal Composition (1993) where, as Briony Fer has pointed out, the remains of constructivist composition are figured like so much spattered detritus.12 The diagonal lines of the composition and the bright, clear colours are presented as the remains of constructivism on the model of a set of bones, or the triangular carcass of a half-eaten Sunday roast; the dirty piece of soap the stand-in for this ‘matter out of place’ in the body of the photograph. We are given here a sense of photography as a collection of borrowed parts of past painting and sculpture.

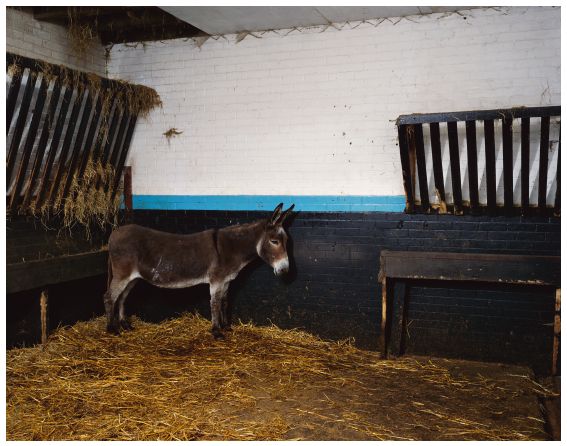

Steve Edwards has pointed to a similar disarrangement of parts, which in this case is rendered explicitly as bodily, in Wall’s A Donkey in Blackpool (1999, plate 4), in which, he suggests, the two mangers shown at right and left of the central donkey make us think of the animal’s rib-cages:

The mood of Wall’s photograph turns darker . . . at the point that the beholder recognizes those two mangers as the external reflection of the donkey’s interior – as two sets of splayed ribs, as if the animal’s carcass had been cracked open along its backbone. . . . The central, dry hollow of the picture space is now the cavity of the donkey’s chest and the beholder’s gaze is directed into the interior of the animal’s body.13

I want to build on this analysis, which I find convincing, to move from the particular case to a wider argument about the disorder of pictorial structure in Wall’s work. The in-and-out wriggle or zigzag of reading which Edwards alerts us to, in and out of the donkey’s carcass, is cued for us, I want to suggest, by the flattened, weird corner of the room Wall has been careful to include.

This corner-construction is a key form or pictorial structure found in many of Wall’s works. Of course his oeuvre is carefully constructed so that there isn’t one thing that can be said to be true in all his works. (Indeed, this is a feature of its particular condition, this carefully managed construction of variation.) Nevertheless, a left-or rightward slanting, diagonal corner, which is flattened out again across the remaining lateral extent of the picture is a feature of many of Wall’s works. For example, in Stereo of 1980 (and by the way, I think the close similarity in composition between A Donkey ... and Stereo suggests rather an obvious joke, along the lines of ‘hung like a ...’); and in No (1983), Man in Street (1995), and A Double Self-Portrait (1979).

The function of this feature, or how it reads, is as a weird wrinkle or wave in space which somehow flattens or compresses volume. It is a way of building space into the picture, but at the same time somehow ironing it out: an in-and-out structure, that, as it returns to the lateral plane, functions as if sewing the picture space to the surface. It is characteristic of Wall’s sense of ‘composition’ – of the slight over-emphasis he places on it – that this lozenge of space should be ‘offbalance’, as though ‘thrown off in a kind of lunge sideways, this extra portion of space then gathered in, looped or lassoed to the rest, like an off-cut; or perhaps an extra pictorial limb. It is an extra portion we might want to call, following Christian Metz, a ‘part-space’, on the model of the psychoanalytic concept of the ‘part-object’.14 The expanded picture space that is composed by the inclusion of such fragments is something that seems to be crucial to Wall’s sense of what a picture is. And the uncanniness or sense of excess about this, its slightly unpredictable springload of psychic affect, is something Wall seems to think of as a strong aesthetic quality.15

4 Jeff Wall, A Donkey in Blackpool, 1999. Transparency in light-box, 195 × 244 cm. Basel: Kunstmuseum Basel. Photo: © Jeff Wall. Courtesy of the artist.

Many people have called Wall’s work uncanny and this description seems justified: the work is rife with doubles; split with multiple, bent picture spaces; fixed by frozen geometry; artificially lit but curiously unilluminated; saturated with all-over colour yet curiously, I think, colourless; full of dead pictorial remnants which are uncannily reanimated. And yet, the uncanny does not explicitly feature either in the account Wall gives of his own work, or the account of it given by Michael Fried, who uses Wall as foundational to his new account of contemporary pictorialist photography.16 Instead, the terms used in the lexicon for the new art-photography, which Fried uses, and which Wall, to an extent, shares with him in his own critical writing, are tradition, composition, unity, intention and medium. (Nevertheless, as I have indicated above, I think there is a little space to be opened up between Fried’s art theory and Wall’s, which I take to be more open to, for example, the positive aesthetic possibilities of the uncanny.)

Fried has extended these terms to the interpretation of the work of Thomas Demand. In an essay published in Artforum in 2005, Fried argued that Demand’s work rescues photography from chance – the obliteration of authorial inscription which it always threatens – by restoring to it ‘intendedness’. Every single thing in the photograph is clearly artificial, made out of coloured paper by the artist, and therefore clearly all a sign of the artist’s will. Building on this, Fried argues, Demand’s photographs ‘thematize or indeed allegorize intendedness as such’ in a way that is, for Fried, the hallmark of a serious art medium.17 I shall say outright that this seems to me a bad reading of Demand; none of the work’s distinctive qualities or effects seems described or captured by this account. Furthermore, I would want to detach myself from what appear to me to be the critical stakes of this argument: the apparently blatant wish to reinscribe the artist as explicit foundation stone for a new modernist aesthetics, reinstating the notion of a medium behind which stands the figure of the artist – ‘intend-edness’ seems so transparent a restoration of what Barthes called the Author-God. Beneath this restoration, the ultimate aim would appear to be to find a way to attribute to photography the kind of’autonomy’ once thought within modernism to attach to the mediums of painting and sculpture; an aim which seems to me open to question. Nevertheless, it is a characteristic (and I think excellent) feature of Fried’s method to challenge those who might disagree with his analysis to offer a better account of the pictures, interpretation being decided one way or the other in the end by this test. My excavation up to this point of key features of Wall’s pictures prepares the way for the account I propose to offer in this chapter to meet this challenge, offering in what follows an alternative description of Demand’s work.

The term I want to reclaim for Demand is visceral. For me, Demand’s work recalls that uncanny ‘squirming’ life of dead things which Max Kozloff described in his essay on soft sculpture.18 This reaction is admittedly a personal one, and perhaps it is not widely shared. After all, ‘visceral’ is not a word much used in connection with Demand’s work in the current literature. Nevertheless, I believe that it captures certain aspects of the works’ distinctive aesthetic qualities which are widely felt, even if they have not, to date, been voiced. There are two key qualities which I mean my use of the word ‘visceral’ to capture. The first of these is ‘interiority’. These pictures are all about the interior, I want to say. Indeed, that there is no exterior is crucial, I would argue, to their peculiar affect. Hence the particular thrill of those images which seem for a moment to suggest the outside world – as, for example, in Pit (1999), where the gleaming, slick surface of the yellow raincoat gives the viewer a hint of rain, as though its wearer had just come in from outside; and yet that we know there can be no outside surely is what accounts for the peculiar charge of the picture. Similarly, in Tavern no. 2 (2006), the dramatic tension of the work depends upon the slightly open window on the right, which seems to offer the viewer a ‘way in’. This inwards-leading dynamic is intensified as Tavern is one of the few images Demand has made in series, and as the series progresses, we seem to travel further and further into the house, exploring room by room, and ending in the cupboard which is perhaps where the little boy in the related newsstory died.19

‘Interiority’ is signalled in a number of important ways in Demand’s work, and in the various permutations of this theme, a certain slippage occurs, from one to another sense of what kind of ‘interior’ is at stake. For example, a sense of interior space colonizing exterior space plays out importantly in Demand’s design for exhibition installations, particularly his installation at the Serpentine Gallery in London in 2006, for which he had wallpaper printed to the design of the ivy in Tavern no. 2.20 In the rather extraordinary photographs of this installation published in the exhibition catalogue, the curved roof of the gallery produces the illusion that the space in the gallery is being tipped up and pushed out, evacuated from the picture, very much as though the gallery walls and floor formed one allover surface; as glossy and lacking in any volumetric depth as one of Demand’s own photographs.

Interiority is also cued by the fact that Demand’s works are made from media images – images which, we are aware, we may have previously ‘consumed’. This helps explain the curious sense we have when we look at them – a sense which cannot be pinpointed precisely as a specific memory – that these pictures seem to have come somehow from ‘inside’ us. This sense is intensified by the powerful editing to which, we sense, the images have been subjected: we do not need to compare each one against its source image to know that certain things have been silently and purposefully removed (for example, there is no text on any of the labels or papers). Demand’s cutting, cropping, and editing of his source photographs – and above all his decisive depopulation of them – in its unsettling, unreasonable, and determined efficiency, seems to imitate the operations of our own interior mechanisms: the selective obliterations of forgetting, perhaps, or the distortions of the dreamwork, or, simply, the systematic yet irrational, deeply unconscious, somatic processes of digestion.

Furthermore, the works signal (in a different sense) ‘interiority’ in being keyed to one another. Every work in Demand’s oeuvre is constructed as though a part of one giant body; each part relationally bearing on the other. Sink (1997), for example, Demand says he made because he noticed that all his works up to that point were rectilinear. He calls Sink ‘a precious counterpart to my other works’, and similarly, Panel (1996), which he says ‘balances and redistributes the tension between the other works’.21 The whole corpus thus behaves as one, mutually inflecting, organism.

To be clear, I am not suggesting that all these senses of ‘interiority’ are the same. What I am saying is that it is notable that Demand’s work across its whole extent pursues these different senses of ‘interiority’, and that the cumulative effect of these pursuits of ‘internal’ over ‘external’ space and reference is to make Demand’s, overall, a peculiarly ‘inwards-looking’ body of work.

In this respect I am to a certain extent simply following Fried and other commentators on Demand. After all, the clearest sense in which there is no ‘outside’ in Demand’s work is that it abandons the reference to the external world which supplied a sustaining support and rationale for most twentieth-century practices of photography, finding its reference points instead in the relatively more ‘internal’ world of compositional reference to other pictures. Images which appear to reference real things photographed in the external world – real kitchens, real bathrooms and so on – are in fact photographs of studio-built, interior sets, and their reference point is really to other photographs. Thus an embeddedness in the external world, which was one of the things taken as most fundamental to photography in its twentieth-century histories, is precisely what Demand’s work appears to have abandoned.

It was Wall of course who licensed this abandonment, by founding the tradition of staged, or ‘tableau’ photography, whose legibility depends on – and whose support is provided by – an internally erected armature of compositional references to other pictures. But where Fried sees ‘intendedness’ in this, and an achievement at last of a kind of autonomy for photography, to put it on a par with other modernist mediums, I see something other: that there is no ‘outside’ to Demand’s system does not render it, I think, precisely the space of a rational mind. Rather, I suggest, Demand’s mutually inflecting system of relations between large-scale photography and studio-built paper sculpture describes a space of the irrational body. It is for this reason I have called Demand’s work ‘visceral’, aiming by this term to encompass all these different, but mutually inter-relating, senses of interiority and to bring them under the claim that ultimately the register of their cumulative functions is bodily.

Demand’s works are notably free of bodies. Therefore it may seem odd that I take the bodily to be such a key term for interpretation of his work. My first and most important justification for this step is that it is based on my – and I think a shared, if unarticulated – aesthetic response to the works. My claim is that the different kinds of pursuit of interiority in Demand’s pictures and their modes of display provoke strong bodily reactions from the viewer: of claustrophobia, of airlessness, and of an inward shudder or quiver, like nausea, as though the pictures led inwards into our own bodies. This is avowedly a personal response, and yet I place strong strategic and rhetorical emphasis upon it. I do this firstly, and following Fried in this respect, because I place considerable importance on founding the task of interpretation on such response, and second because other interpretations of Demand’s work so far make no place for a similarly strong characterization of their aesthetic effects – surely a central task for criticism which in this case has been neglected. Nevertheless, there are other justifications. One justification is that, to recap, I think that a certain model of composition, or rather the disarrangement of a certain model of composition, is fundamental to the work of the new ‘pictorialist’ photographers of whom Wall and Demand are two. A good account of this classical model of pictorial composition is provided by Barthes to the effect that the classical ‘tableau’ is founded on a model of balanced arrangement of parts whose fundamental model is the human body. Where this is disarranged – as is the case, I tried to show, in Wall – the picture can be persuasively read as resembling a scattered collection of body parts which fail to cohere, and which possess a certain uncanny quality of affect.

Finally, a third reason for taking the kind of ‘interiority’ which is at stake in Demand’s practice overall to be a bodily interiority is because what we are looking at is a practice in which a sculptural body is swallowed up inside an image and within a photographic practice which supersedes it. Specifically, we should remember, Demand’s is a practice in which the sculptural object is created by being externalized from the inside of a photograph, and then is re-digested, or made to disappear again, repeatedly, systematically, ‘inside’ the image. In this way, a certain deep irrationalism of sculpture, of the sort described by Kozloff in his essay on soft sculpture of the 1960s, is at work at a subterranean level in Demand’s photographic practice. Yet it is equally important that this sculptural logic should disappear again, swallowed up in a convulsion of the newly elastic and encompassing body of photography.

5 Claes Oldenburg, Bedroom Ensemble, 1963 (1 of 3). Wood, vinyl, metal, artificial fur, cloth and paper. Installation space 3 × 6.5 × 5.25 m. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada. Photo: © Claes Oldenburg. Courtesy of the artist and the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

We should remember, I think, that in Sherrie Levine’s photographs After Edward Weston, a buried sculptural figure was also at stake, since the twisted poses adopted by Weston’s son, Neil, were modelled after the poses of Classical statuary. Here a double obliteration of sculpture was at work, burying the memory of the marble figure in the living flesh of the body before its second immurement in the glassy surface of the photograph. Yet, in addition, the fact that in his essay Kozloff was describing the work of Claes Oldenburg, amongst others, should suggest to us that in the prehistory of Demand’s work stands Oldenburg’s Bedroom Ensemble of 1963 (plate 5). Bedroom Ensemble is a frozen composition which displays sculpture as already pictorially infected before it is photographed.22 This bent, weird, photogenic sculptural group was produced by being worked through the mechanism of the picture (in this case, a perspective diagram rather than a photograph) and back out again, to produce the sculptural object as remnant or left-over. As a result, we see a deep, perverse, coding of sculpture at the level of, or within, the photographic surface. The characteristic, if profoundly strange, product of this in Oldenburg’s case is the distinctive form of sculptural ensemble (or three-dimensional ‘picture’) called the ‘tableau’.

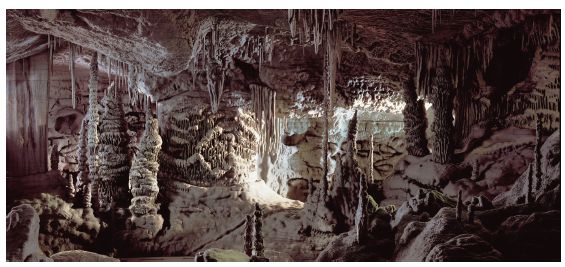

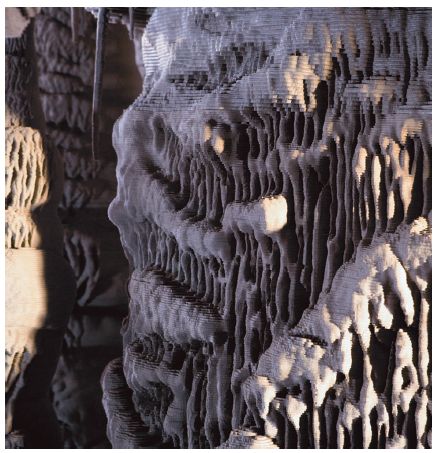

6 Thomas Demand, Grotto/Grotte, 2006. C-print/Diasec, 198 × 440 cm. Photo: © Thomas Demand, VG Bild Kunst, Bonn/DACS, London. Courtesy of the artist.

The installation of Demand’s Clearing (2003) suggests comparison with Oldenburg’s Bedroom Ensemble as a ‘tableau’ built to a fixed, pictorial viewpoint. Perhaps an even more compelling comparison is with Demand’s Grotto (2006), with its built-in digital pixel incorporated in the cardboard model (plates 6 and 7). Although Demand’s desire to bring the condition of the photographic deeply into the materiality of sculpture is most visible here, where the digital pixel is reproduced in layers of paper, this kind of photogenic distortion is a part of all his sculptural constructions, which are built not in ‘correct’ proportion but so that they appear in correct perspective in the photograph.23 In Grotto the results of this condition are made manifest as something like a corruption of the sculptural object by the picture, the object almost rotting from within as it takes on aspects of this digested form.

What, then, is the name for the territory of the visceral, for the giant body which I see Demand’s corpus as forming? Barthes’ description has already pointed us to what I think is the answer; and here again some of the terminology introduced by Deleuze in his account of the (similarly photographically infected) practice of Francis Bacon is helpful. The irrationalism of Demand’s sculptural practice – its inability to support itself and its parasitic dependence on, or engulfment within, the second medium of photography – suggests the disarranged anatomy of the ‘body without organs’ that Deleuze describes.24 The body without organs, Deleuze says, is a body not without organs so much as a body without organization, which cannot, therefore, be self-supporting.25 Similarly, photography in Demand’s production is not self-supporting, but must ‘prop’ itself on some support in a parasitic system. In Demand’s work, photography and sculpture are ‘propped’ on one another, forced to cohere by the invisible operations of the picture, to which both mediums, in a stunted, deforming way, must conform.

7 Detail of Thomas Demand, Grotto/Grotte, 2006. C-print/Diasec, 198 × 440 cm. Photo: © Thomas Demand, VG Bild Kunst, Bonn/DACS, London. Courtesy of the artist.

Demand’s photography works on the body of sculpture in a way I believe is similar to the way Wall works on the body of painting. In each case, the remaindered medium is rendered bodily, as something dead but reanimated, working in an airless vacuum. Yet in neither Demand’s nor Wall’s case does this operation produce ‘photography’ as a medium in its own right. For in each case, photography appears only to ventriloquize the deforming force of a prior ‘picture’. And thus I think it is right to call the picture a force, in the Deleuzian sense, rather than a medium, recalling Deleuze’s description of the scream in Bacon’s paintings of Pope Innocent X.26 For the ‘picture’ is not something that has its own material integrity or set of working procedures. Rather, it is something which speaks through photography and is made visible only in the distinctive, convulsive, twist which is its operation of deformation on the receiving body of the mediums of painting or sculpture.

From a more art-historical viewpoint, this sense of the ‘picture’ as an abstract, un-mediumized structure – which enables a migration between mediums, from painting to staged photograph or from press photograph to paper sculpture and back to photography – is precisely what Douglas Crimp originally identified in his catalogue essay of 1977 and in the modified version published in October in 1979. Crimp described in that essay the particular force of the picture as being to de-mediumize, or to enable transfer across mediums.27 It is for this reason that Crimp further identified in the ‘picture’ a particularly uncanny quality: the property of achieving a ghastly and yet all the more forceful ‘presence’ without being fully ‘present’, which he likened to the effect of the ghostly doppelganger described in the short story ‘The Jolly Corner’ by Henry James. Returning to the problematic of ‘Pictures’ in his later essay, ‘The photographic activity of postmodernism’, Crimp argued specifically that it is the stripping of the ‘aura’ of the work of art which results in the curious, uncanny, intensities of effect attaching to the works of the artists he groups under the heading ‘Pictures’. These are the result, he says, of a kind of return of aura to the artwork, but this return is not a recuperation. Rather, in the work of artists such as Levine, aura is displaced, and shown to be ‘only an aspect of the copy, not the original’.28

This description of works possessing simultaneously a deafening emptiness, or lack of ‘art’-value, and at the same time, a heightened and uncanny aesthetic effect is very close to that articulated by Walter Benjamin in his essay ‘The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility’, when he describes the peculiar effects of the photographs of Eugene Atget. Famously, Benjamin described Atget as photographing deserted Paris streets ‘like scenes of crime’.29 He also said Atget’s photographs ‘suck the aura out of reality like water from a sinking ship’.30 Both these descriptions may remind us of the work of Demand.31 Demand presents empty scenes which, even more than Atget’s, are guaranteed to be empty of people (because we know they are cardbard stage sets), and which in several cases actually are scenes of crime (as for example in Bathroom, of 1997 and Corridor of 1995). Like Atget’s photographs, Demand’s seem to have had something pumped out of them, leaving them airless and confined. Thus, in the work of both there is a simultaneous sense of the emptiness of non-art and of curiously intensified and uncomfortable effect, summed up in the way that, in Benjamin’s descriptions, Atget’s work appears emphatically de-auratic and uncanny.

Benjamin’s descriptions, it may be thought, open a door to let the notion of ‘aura’ back in. Ostensibly Benjamin situates Atget as pinpointing the moment when cult or auratic value has fled the photograph and the human countenance has vacated the scene. Atget’s emphatically deserted photographs apparently dramatize the moment when new and de-auratic values come to the fore in photography. Yet the highly suggestive terms in which Benjamin praises Atget (compared, for example, to his praise of the similarly de-auratic August Sander) may arguably be thought to mark the moment of a resuscitation of aura: or something like it. After all, aura and the uncanny bear a buried relationship to each other throughout Benjamin’s essays on photography – in the way he suggests that people captured in old photographs have the capacity to ‘touch’ us in the present, and in his suggestion that early portrait photographs preserve a buried layer of past time, or some quintessence of the sitter, in the light seared into the plate.32 However, as Crimp has shown, this is the characteristically ‘double’ effect achieved where aura has been dis-placed, rather than retrieved. In the work of Thomas Demand, we seem to see a re-staging of this vision of Atget: the auratic returns and is re-written or writ large as a dramaturgy of the uncanny. Demand’s engagement of the uncanny in his photography is made explicit in a work such as Ghost; the only work of his to suggest a ‘presence’ in the scene. Altogether, Demand’s photographs might seem to confirm Crimp’s diagnosis, that ‘in our time the aura has become only a presence, which is to say, a ghost’.33

8 Jeff Wall, The Crooked Path, 1991. Transparency in light-box, 119 × 149 cm. Friedrich Christian Flick Collection. Photo: © Jeff Wall. Courtesy of the artist.

Furthermore, we should remember that this phenomenon – the stripping of the ‘aura’ of the work of art and the curious, uncanny intensities of effect which are resultant properties of the commodified art-object – is not a property or power belonging to photography in itself. Rather, as Benjamin himself described, it is the mark or sign of an increase in the potential for commodification of the artwork enabled by newer technologies of mechanical reproduction; a phenomenon brought about by photography, but then transferred to works in other media. In different language, we might say it is the visible sign of the operations of the picture, as Douglas Crimp first identified it. The ‘force’ at work in Demand’s or Wall’s production is not identical simply with ‘photography’, then, for it is a structure of quotation or parasitic dependence between images in different media that is only, if repeatedly, ventriloquized through photography. Recognition of this runs counter to the suggestion that Wall’s or Demand’s work represents the moment of photography’s realization as an art medium, as the recent writings of Fried and Wall have argued.34

9 Eugène Atget, Chemin à Abbeville, before 1900. Albumen silver print, 24 × 18 cm. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden. Photo: © 2009. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/SCALA, Florence.

Again, the similarity between Demand and Atget is helpful here. Despite the differences in their historical situations, the problematic of commodification is visible in each. Central to the economics of Atget’s practice, after all, was the effort to take up into photography forms of the picture which had been established in other mediums – the tableau de Paris, for example, the ‘topographical view’, the pittoresque, and the étude.35 This is something demonstrated in the comparison which was published in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1981 catalogue of Atget’s works, showing on the far left, a lithograph after a drawing by A. Duthoit, from before 1853, in the centre, a photograph by Charles Marville from about 1851, and on the right a photograph by Atget from before 1900.36 Viewing these and similar correspondences, we may say that Atget’s work in fact constitutes an early example of the photographic appropriation of earlier forms of picture, which had flourished in painting and prints before the invention of photography. This indeed is the source of their blankness, their emptiness – the fact that, as has often been noted, Atget’s works are often indistinguishable from countless similar photographs taken by other photographers around the same time. This is the reason for their ‘anti-art’ value, as commentators on Atget have often insisted.37

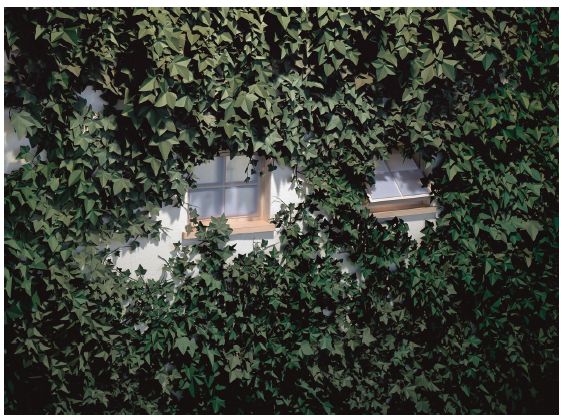

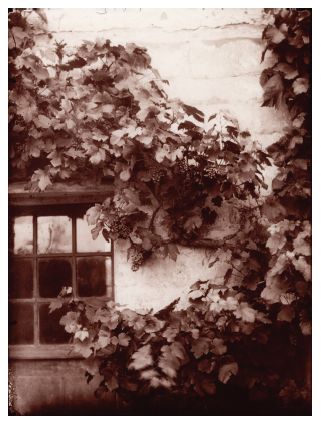

However, the point is not simply that we can discern in Atget’s work compositional appropriation. The forms of picture Atget retrieves are rather different pictorial structures to the specific compositions of particular Salon grandes machines or individual masterpieces such as The Raft of the Medusa; and the form of reference is rather different to that of quotation in homage to the Old Masters. In Atget, what we seem to see instead are older forms, part-objects, and remnants of pictorial structure. The coin, for example, or corner – a term Atget often used to categorize a courtyard scene – is a more stubborn repeated structure which is resistant to interpretation.38 What we see at work here is the mute logic of the ‘picture’, which, I have suggested, we can also see at work in the photography of Wall and Demand. Although critics have mainly focused on Wall’s deliberate quotation of compositional fragments from grand Salon paintings, we can see the kinds of odd leftovers and remnants of less elevated pictorial structures characteristic of Atget’s photographs also in Wall’s work; for example in the comparison between Wall’s The Crooked Path of 1991 (plate 8) and a pre-1900 photograph by Atget called Chemin a Abbeville (plate 9). We also see similar stubborn, ineradicable, part-objects of pictures surviving in Demand’s work; as in his Tavern 2 (plate 10) and one of Atget’s Vines, again, from before 1900 (plate 11).

This survival of what is not quite pictorial form, but is instead, pictorial part-structures, points, I want to suggest, to the functioning of something which, again, is not exactly in the register of deliberate quotation or intentionality, but is instead something more corporeal than this – something more like an obdurate persistence. At the same time, this gives us an understanding of the ‘picture’ less as compositional grand scheme, or continuing tradition, but instead as a more visceral, persistent and form-seeking structure of the image. The ground the ‘picture’ occupies is a bassesse of visual form where grand Salon paintings and banal visual documents, ‘charged’ news photos of scenes of crime and ordinary snapshots, are all swarmed over by the market appetite for visual consumption and repetition, producing a form of stubborn visual ubiquity that is the hallmark of the ‘picture’. We can see as much, I want to suggest, in the fact that the persistent form of the coin in Atget’s photographs is the same as that corner-structure I have described in Wall’s photographic compositions, which itself echoes the shape of the mattress in his Destroyed Room, the shape of the raft in Géricault’s Medusa, or the disposition of the figure in Etant donnés. This base level of pictorial form operates to undo the kinds of oppositions it is conventional to draw in photographic histories, between ‘documentary’ and ‘cinematographic’ in the work of Wall, for example, just as much as it undoes notions of quotation or tradition or continuity at the level of conscious intentionality.39 It speaks against Michael Fried’s account of ‘intendedness’ as the root-structure of Demand’s photography, even as it points to the symptomatic reason for Fried’s valorization of this quality in an oeuvre which is deformed, I have suggested, by the operations of the market as these play out through the processes of commodification and repetition between media. Finally, the parasitic operations of the ‘picture’ speak against the modernist idea of a ‘medium’ and point instead towards the system of production-via-prostheses which Deleuze has called the bachelor machine.40

10 Thomas Demand, Tavern/Klause II, 2006. C-print/Diasec photograph, 178 × 244 cm. Photo: © Thomas Demand, VG Bild Kunst, Bonn/DACS, London. Courtesy of the artist.

11 Eugène Atget, Vigne, before 1900. Albumen silver print (gold-toned), printed 1980, 24 × 18 cm. Modern print by Chicago Albumen Works from the original negative in the Abbott-Levy Collection. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: © 2009. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/SCALA, Florence.

The bachelor machine as the system of production which attaches to the body without organs is an idea suggested by Rosalind Krauss to describe Sherrie Levine’s sculptural production, her 1989 series, The Bachelors (After Marcel Duchamp), in particular.41 Levine caused some dismay amongst her former champions when she moved away from the method of photographic appropriation and returned to the sculptural and painting practices she had earlier appeared to reject. Levine’s turn to the laborious re-making of paintings and sculptures by modernist masters seemed to mark a regressive return to ‘craft’, seemingly of a piece with her increasingly unsettling insistence in interviews that she had never intended not to make ‘art’.42 Yet Krauss’s application of the idea of the bachelor machine to Levine’s Bachelors suggests a way we might understand these works as continuous with her previous photographic practice. The Bachelors series comprises six sculptural objects made out of frosted glass, each individually displayed in its own glass vitrine. The design of each object is taken from one of the Malic Molds – the forms of the ‘Bachelors’ – which appear in the lower half of Marcel Duchamp’s large picture on glass, The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23), (see plate 5 in Christine Conley’s chapter in this book) also called the Large Glass. The relevance of photography to the Large Glass has long been observed by commentators, who have argued that Duchamp conceived the work in part as a materialized version of the workings of photography, or as another way of making a picture which, like a photograph, is developed on glass.43 Levine’s series comprises sculptures extracted and materialized from a glass ‘photograph’, but re-embedded within their original source by sharing the same extended material surface – a form of production similar to Demand’s as I have described it.

Displayed as they are in individual glass vitrines, we see an additional dimension to the sense in which Levine’s sculptures and her source-image share a common surface: the glass objects cast reflective doubles onto the glass walls of the specially built cases. The effect recalls Brassai’s ‘involuntary sculptures’ photographed on backlit glass; where, as Briony Fer has pointed out, the sculptural object appears almost as a stain or cast shadow against the light.44 In both Levine’s and Brassai’s works, what we see is the collapse of sculpture into the surface of the photograph. This example helps bring out a final, important dimension of Demand’s practice: its loss and consequent fetishization of surfaces. For if the skin is the largest organ of the body, then the body without organs is a body without skin, its skin or ‘surface’ only its largest disarranged or displaced part.

This loss of and consequent confusion over surface is apparent in another of the links in the genealogical chain I am constructing for Demand’s production: Hiroshi Sugimoto’s 1999 black and white photographs of waxworks. Here, the painted surface of waxwork figures blends with the lush, creamy whites and velvety blacks of Sugimoto’s prints, giving the resulting images a curiously painterly quality. The confusion that the spectator feels on first seeing these works – are they paintings, photographs, or something else? – is very like the confusion often felt on first confronting Demand’s works. The painterliness of Sugimoto’s images, a consequence of this particular blending of sculpture with photography, is, I suggest, a compensation-structure which at the same time points to the deeply intermedia condition of this work.

In his well-known essay on photography in conceptual art, Jeff Wall describes the loss of the modernist painting surface as a key loss in the history of the picture – a loss that even photographic pictorialism cannot restore. Instead, he argues, the contingency, disarrangement and freshness which the modernist painting surface signalled must be appropriated by pictorialist photography, which must take over the spontaneity and look of non-composition in the depicted scene. Hence Wall urges the importance of reportage photography as the next territory which the ‘picture’ may colonize.45

‘Reportage’ or press photography is the kind of photography Demand almost exclusively pursues. Thus Wall’s diagnosis might be thought to pertain especially to Demand’s work. And yet, I have suggested, such distinctions of category are undone in Wall’s and Demand’s work by the hungrier, more incessant, recycling logic of the ‘picture’. Thus, the significance of the loss of a painterly or sculptural surface in their works is at another register. The consequence of trying to rebuild qualities originally attached to a ‘surface’ in the interior of the photograph, is that in Demand’s case we are given a kind of sculpture in which the outside has migrated to the inside – for which, as a result, there is no skin; that is, no boundary marking the ‘outside’ of an object. Instead, as a secondary compensation, we are offered numerous painstaking replica surfaces. Indeed, Demand’s work sometimes looks as though it is trying to become a replacement model for all the different kinds of surfaces in the world – see for example the gleaming surfaces of the gold bars in Bullion (2003), the shadow-dappled leaves in Clearing, the rough straw in Stall (2000) or the pristine, lurid green grass in Lawn (1998).

As primary compensation, however, is erected the photographic surface, yielding an all-over visibility, an utterly glazed and impermeable, miraculously whole and intact skin which functions almost as a kind of prosthesis for the lost skin of the sculptural object. This is the condition, indeed, of the works by other artists I have discussed – the collapse of the sculptural object into the photographic surface produces the photograph as prosthetic ‘skin’, which can present in various ways. One possibility, for example, is to be lush, creamy and explicitly compensatory, because painterly, like Sugimoto’s. In Wall’s work, the need for an investment in a hard, glazed, impermeable, prosthetic surface is made apparent in one of his earliest works, the Picture for Women (1979), where the basilisk eye of the camera appears embedded within the reflective surface of the mirror, which is presented as an explicit double of the surface of the photograph. Wall’s fetishism for surfaces is also apparent in his discussion of glass architecture in his essay on Dan Graham, and more subtly, in the sheer glut of visual detail and ostentatious pictorial clarity of his works, which suggests the kind of fetishism in which nothing is hidden, but everything is irrelevant, the wealth of detail providing a prosthetic surface which proves the most effective mask.46 Above all, of course, Wall erects as prosthesis the illuminated light-box surface. Indeed, whilst critical attention has been paid to the lit-up quality of Wall’s light-boxes; no one I think has yet remarked on the doubled, impervious surface which it lends to the photograph, which I suggest we can now see as a protective skin or carapace. The shiny surfaces of Demand’s photographs (which are habitually laminated to Plexiglass) obviously reference Wall’s light-boxes, as, we might suggest, they also call to mind Gerhard Richter’s mirror-paintings.

The surface as prosthesis is the deeper significance of the ivy wallpaper which covered the walls in the Serpentine installation of Demand’s works.47 ‘Ivy on ivy’, as Beatriz Colomina has written, ‘cladding on cladding’ – this installation strategy provides a demonstration not only of the in-and-out movement of the work and the way it rewrites all external space as internal, but also functions as a demonstration of the nervous intensification of surface that we see in Demand and the compensatory function of ‘skin’ as a replacement surface erected for sculpture by the photograph.48 This sort of prosthetic operation mirrors the mode of production that is characteristic of bachelor machines, as Krauss described it. Within bachelor-machine production, mediums are characteristically produced by taking another medium as object, resulting in a very specific intermedia condition. Mediums for mediums, then, as a set of prosthetic operations.49

In conclusion, I contend that neither Wall nor Demand can be used to revive modernist aesthetics. Fried, I think, in seeing Demand as rescuing photography from contingency and performing an elaborate demonstration of ‘intendedness’, not only understands this as at last elevating photography to the ‘status’ of a medium, but wants to see this performance as exemplary for our relationship to the world. It is a soothing restoration of a certain model of our relationship to things, healing the wound which so many (Roland Barthes chief among them) have understood photography as representing, and re-producing it as an art capable of modelling for us an exemplary ‘autonomy’. I don’t think this accounts for the particular aesthetic qualities of the work, nor the deeply embedded force of deformation encoded in the sculptural twisting to the photographic surface which it performs. Nor does it produce an art-historical genealogy such as the one I have shown can be constructed for this mode of production. Nor, finally, does it describe the way in which Demand’s work shows photography and sculpture as grasping not the world but only each other, in a mode of desiring, convulsive and deforming production. In sum, the body without organs is too pervasive a presence within Demand’s works to allow them any purchase on such foundation stones of modernist aesthetics as medium, aura or intentionality. We have instead to recognize in them a postmedium condition, within which the picture spreads out like ivy, over and within bodies of painting and sculpture which are remaindered as part-objects and part-spaces in the resuscitated photograph-fetish.

Notes

1 Douglas Crimp, ‘Pictures’, in Brian Wallis, ed., Art after Modernism, New York, 1984, 175–87. This is a reprint of the version in October, 8, Spring 1979, 75–88. For Wall’s use of the term ‘picture’ see most notably his essay, “‘Marks of indifference”: aspects of photography in, or as, conceptual art’, in Ann Goldstein and Anne Rorimer, eds, Reconsidering the Object of Art: 1965–1975, Los Angeles, CA and Cambridge, MA, 1996, 247–67; but also his ‘Frames of reference’ in Jeff Wall: Selected Essays and Interviews, New York, 2007,17381, and his much earlier, ‘Unity and fragmentation in Manet’, in Jeff Wall: Selected Essays and Interviews, 77–83. A recent article by Diarmuid Costello, ‘Pictures, again’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, 8, 1, 2008, 11–41, also considers the interest of thinking about Crimp’s term ‘picture’ in relation to recent large-scale photography and the art-theory of Michael Fried.

2 See Crimp, ‘Pictures’; Crimp, ‘The photographic activity of postmodernism’, in On the Museum’s Ruins, Cambridge, MA, 1993, 108–25; Abigail Solomon-Godeau, ‘Photography after art photography’, in Brian Wallis, ed., Art After Modernism, New York, 1984, 75–85, and Solomon-Godeau, ‘Winning the game when the rules have been changed’, in Liz Wells, ed., The Photography Reader, New York, 2003, 152–63.

3 Wall, ‘Frames of reference’. Abigail Solomon-Godeau contrasts ‘art photographers’ to ‘artists using photography’ and groups Levine with the latter in her essay, ‘Winning the game when the rules have been changed’, 155.

4 Wall, ‘Frames of reference’, 173.

5 Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, trans. Daniel W. Smith, New York, 2004, 61–2.

6 The year before he made Destroyed Room, Wall made a triptych, Faking Death, using his new support, the photographic transparency. This work was first exhibited with Destroyed Room in 1978 and exhibited twice more after this before being withdrawn by the artist from his oeuvre around 1980. For details, see Theodora Vischer and Heidi Naef, eds, Jeff Wall: Catalogue Raisonné, Basel and Gottingen, 2005, 275.

7 Table is identified as Richter’s ‘first painting’ in these terms by Robert Storr in Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting, New York, 2002, 29. Richter confirms it in an interview with Storr; see ‘The day is long: interview with Gerhard Richter by Robert Storr’, Art In America, 90, 1, January 2002, 73.

8 ‘Diderot, ‘Composition in painting’, Encyclopedia vol. III (1753), as quoted by Roland Barthes in his essay, ‘Diderot, Brecht, Eisenstein’, in Image Music Text, trans. Stephen Heath, London, 1977, 71. For a translation of Diderot’s full essay, see Beatrix L. Tollemache, Diderot’s Thoughts on Art and Style, New York, 1893/1971, 25–34.

9 Barthes, ‘Diderot’, 71–2.

10 Wall, ‘Unity and fragmentation in Manet’, 178.

11 Barthes, ‘Diderot’, 71–2.

12 Briony Fer, ‘The space of anxiety: sculpture and photography in the work of Jeff Wall’, in Geraldine A. Johnson, ed., Sculpture and Photography: Envisioning the Third Dimension, New York, 1998, 234–5.

13 Steve Edwards, ‘“Poor Ass!” (A Donkey in Blackpool, 1999)’, Oxford Art Journal, 30, 1, March 2007, 52.

14 ‘I would say that the off-frame effect in photography results from a singular and definitive cutting-off which figures castration and is figured by the “click” ofthe shutter. It marks the place of an irreversible absence, a place from which the look has been averted for ever. The photograph itself, the “in-frame”, the abducted part-space [my italics], the place of presence and fullness . . . shares, as we see, many properties of the fetish.’ Christian Metz, ‘Photography and fetish’, in Liz Wells, ed., The Photography Reader, 2002,143.

15 It may be compared, I think, with Wall’s positive account of the effects of ‘a fundamental instability’ produced by the use of mirrors and other devices in the work of Dan Graham and Michael Asher in his essay, ‘A draft for “Dan Graham’s Kammerspiel”’, in Jeff Wall: Selected Essays and Interviews, 11–29. This instability, he argues, ‘throws into doubt their rather severe canonical existence in [Benjamin] Buchloh’s texts; it raises questions about the “progressiveness” so insistently imputed to them, but it may also make them more interesting, complex and productive than they have seemed in functionalist terms’ (28).

16 See Michael Fried, ‘Jeff Wall, Wittgenstein and the everyday’, Critical Inquiry, 33, 3, Spring 2007, 495–526.

17 Michael Fried, ‘Without a trace’, Artforum, 43, March 2005, 202. Fried has recently developed this argument further in Chapter 9 of his book Why Photography Matters As Art As Never Before, New Haven and London, 2008.

18 Speaking of Claes Oldenburg’s sculptures in particular, Kozloff writes, ‘They are taken out of, or removed from, “life”, and yet are found to be preternaturally welling up with it – but life of a different sort, rioting in stunned or dreaming matter. . . . As a result, the experience of Oldenburg’s work is coloured ... by a nightmare sense of conspiracy in which the spectator almost feels himself less organic than the creaturely squirming of all the dead things around him.’ Max Kozloff, ‘The poetics of softness’, in Renderings, London, 1970, 227; 233.

19 For details of the news-story connected to this work see ‘A conversation between Alexander Kluge and Thomas Demand’, in Thomas Demand, London and Munich, 2006, 85–90, where Demand confirms the idea that each of the five pictures is meant to show a different moment in time (89). Mark Godfrey supplies the detail that the child was murdered in the ‘broom-closet’ of the tavern in his review, ‘Thomas Demand: Serpentine Gallery, London’, Artforum, 45, September 2006, 369.

20 Demand also took great care to manage the installation of his exhibition at Fondation Cartier in Paris in 2001, where he hired an architectural firm to design coloured screen/ walls and used a wallpaper designed by Le Corbusier. See Demand’s discussion of this installation in Francois Quintin, ‘There is no innocent room’, in Francesco Bomani et al., Thomas Demand, Paris and London, 2001, 61.

21 Thomas Demand, quoted in Quintin, ‘There is no innocent room’, 56.

22 Briony Fer discusses Oldenburg’s installation in her chapter on the ‘tableau’ in The Infinite Line: ReMaking Art After Modernism, New Haven and London, 2004, 89–90.

23 Demand used at one stage to make two versions of his sculptural objects: one that was in correct perspective and one that was built to look ‘correct’ in the photograph. After a while, the ‘correct’ version fell away harmlessly within Demand’s practice, as if atrophying and dropping off. See Demand, quoted in Quintin, ‘There is no innocent room’, 43.

24 Deleuze, Francis Bacon, 44.

25 Deleuze, Francis Bacon, 47.

26 Deleuze writes that in Francis Bacon’s painting, Pope Innocent × screams ‘as someone ... whose only remaining function is to render th[o]se invisible forces that are making him scream . . . This is what is expressed in the phrase, “to scream at” – not to scream before or about, but to scream at death – which suggests this coupling of forces, the perceptible force of the scream and the imperceptible force that makes one scream.’ Deleuze, Francis Bacon, 61–2.

27 Crimp, ‘Pictures’, 175.

28 Crimp, ‘The photographic activity of postmodernism’, 117.

29 Walter Benjamin, ‘The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility’ (third version, 1939), trans. Harry Zohn and Edmund Jephcott, in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, vol. 4, 19381940, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, Cambridge, MA and London, 2003, 258.

30 Walter Benjamin, ‘Little history of photography’ (1931), trans. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter, in Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland and Gary Smith, eds, Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, vol. 2, part 2, 1931–1934, Cambridge, MA, 1999, 518.

31 The comparison between Demand and Atget is also briefly discussed by Roxana Marcoci in her essay, ‘Paper moon’, in Thomas Demand, New York, 2005, 20.

32 Benjamin, ‘Little history of photography’, 514, 510.

33 Crimp, ‘The photographic activity of postmodernism’, 124.

34 See Wall, “‘Marks of indifference”‘, 252, 266; and Fried, ‘Without a trace’, 202.

35 On the tableau de Paris see Maria Morris Hambourg, ‘The structure of the work’, in Hambourg and John Szarkowski, The Work of Atget, vol. III: The Ancien Régime, New York, 1983, 22. Molly Nesbit discusses the pittoresque and the étude in relation to Atget’s work in her book, Atget’s Seven Albums, New Haven and London, 1992, 71, 29–33. The ‘topographical view’ is discussed by Hambourg in her ‘Notes on plates’, in Hambourg and Szarkowski, The Work of Atget, vol. 1: Old France, New York, 1981,153-4.

36 This comparison is illustrated in Hambourg and Szarkowski, The Work of Atget, vol. 1: Old France, 155.

37 See Rosalind Krauss ‘Photography’s discursive spaces’, in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, Cambridge, MA, 1996, 13150; and Abigail Solomon-Godeau, ‘Canon fodder: authoring Eugene Atget’, in Photography at the Dock, Minneapolis, MN, 1991, 28–51.

38 On Atget’s use of the coin, see Hambourg, ‘Notes on plates’, 161–2.

39 The distinction between ‘documentary’ and ‘cinematographic’ photographs amongst Wall’s works was proposed by the artist and is explained in Jeff Wall: Catalogue Raisonne’, 272. The work I discuss here, The Crooked Path, is classified by Wall as a ‘documentary’ photograph. See chapter by Wolfgang Brü ckle in this book.

40 See Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem and Helen R. Lane, London, 1984, 17–22.

41 Rosalind Krauss, ‘Sherrie Levine: Bachelors’, in Bachelors, Cambridge, MA, 1999, 179–90.

42 See Abigail Solomon-Godeau, ‘Living with contradictions: critical practices in the age of supply-side aesthetics’, in Carol Squiers, ed., The Critical Image: Essays on Contemporary Photography, London, 1991, 66–7.

43 For the connection of Duchamp’s Large Glass to photography see Rosalind Krauss, ‘Where’s Poppa?’, in Thierry de Duve, ed., The Definitively Unfinished Marcel Duchamp, Cambridge, MA, 1991, 433–62.

44 Fer, ‘The space of anxiety’, 239.

45 Wall, “‘Marks of indifference”‘, 248–9.

46 See Wall, ‘A draft for Dan Graham’s Kammerspiel’.

47 Godfrey’s discussion is also useful here; see his ‘Thomas Demand: Serpentine Gallery, London’, 368–9.

48 Beatriz Colomina, ‘Media as modern architecture’, in Thomas Demand, London and Munich, 2006, 44.

49 Krauss quotes Deleuze and Guattari as quoting Marshall McLuhan: “‘the content of any medium is always another medium”’, in ‘Sherrie Levine: Bachelors’, 181.