9

ALMOST MEROVINGIAN: ON JEFF WALL’S RELATION TO NEARLY EVERYTHING

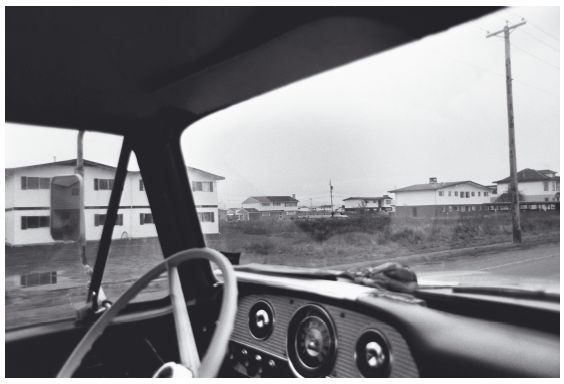

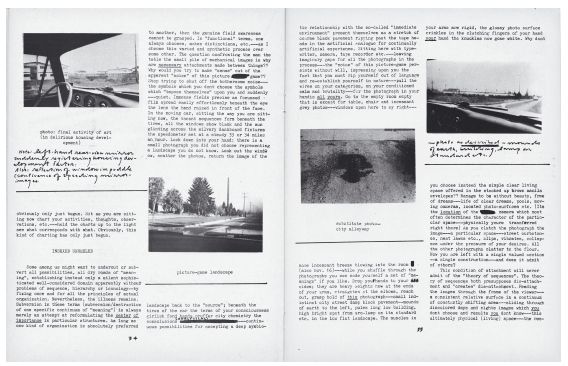

There is reason to think that the most fascinating picture among Jeff Wall’s recent works is one of his apparently least complex artistic statements thus far. The reason for this fascination is precisely that it lacks the usual visual complexity of this artist’s work. At any rate, this is what one might think when confronted with it on a gallery wall. And isn’t After Landscape Manual a truly dull picture? (plate 1) It gives a view from a car, showing the dashboard and the steering wheel as well as, further away, a glimpse of the surrounding landscape, this landscape being itself quite dull. The camera’s point of view implies the accidental situation of a driver sitting in his car and looking out at the suburban environment. Yet, apart from evidence of some uninspired building activity, we are not shown any attractions that would justify treating this image as aiming at art. For an audience accustomed to deciphering the meaning of pictures, it scarcely registers at all. Nor do any formal concerns of the artist make themselves felt, unless we were to take their very absence as precisely Wall’s point of interest. Perhaps it was, for this effect of absence and hollowness was precisely what the artist aimed to achieve some forty years earlier when he composed his Landscape Manual from snapshots he had taken on a drive (plate 2). Landscape Manual became a hybrid work, consisting of both photographs and texts, presented in a low-budget book that spread the images over fifty-six pages, and accompanied them with reflections on their status, their content, and their merit as a communication medium. Obvious parallels between this book and conceptual approaches to humdrum photography in Ed Ruscha’s and Robert Smithson’s contemporaneous works have already been pointed out by many critics and, for the moment, I will not delve deeper into this matter. Suffice it to say that Wall frankly admits the importance of Smithson’s texts for his own work but that this conceals a complex relation. While Wall’s deliberate seesawing between theoretical arguments and a more narrative tone in Landscape Manual is especially close to Smithson’s example, it does not follow that his own contribution is a parodic encounter with journalism, even though he has characterized Smithson’s work in these terms.1 If the picture from his Landscape Manual were parodic, one would expect its blown-up version of 2003 to retain something of that tendency, but it does not. On the other hand, it is not easy to define what it does instead: The stand-alone photograph now lends itself to a framed presentation and facilitates absorptive contemplation. However, its hollowness remains the same; isolated from its original context, the picture’s bluntness becomes even more striking than in the book. No trace of a story is left. We may or may not invent a narrative to contexualize what we see, thus walking the path Wall had laid out when he put a text to the picture back in 1970. Yet the emerging story would probably become ours rather than Wall’s if we did.

1 Jeff Wall, After ‘Landscape Manual’ [1969], 2003. Silver gelatin print, 25.5 × 38 cm. Italy: Collection Avon Campolin. Photo: Courtesy of Jeff Wall and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

2 Jeff Wall, pages 34–35 from Landscape Manual, 1969–1970. Photo: Courtesy of Jeff Wall and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

It will become clear from what follows that this potential effect is in line with the aesthetic implications of other works by the artist, and I hope it will also become clear why Wall may have taken advantage of this new print, which was distributed as a benefit edition, to make a programmatic statement, and thereby to take another step towards the establishment of an increasingly self-referential oeuvre. My claim is that there is a drive behind Wall’s variations of model and style that works as an integrative force. From this perspective, Wall’s attempts to broaden the range of his referential network might be seen to imply a shift in his outlook on his own previous work, without however changing our view of his overall aims. This reasoning is not self-evident. Confronted with Wall’s manifold use of models from the history of Western painting for his transparencies, Jean-Francois Chevrier argued in 1995 that each of these images developed ‘its own specific programme’, and that, while they might be seen as a corpus if assembled in an exhibition space, they nevertheless lack mutual dependency beyond their respective relation to the nature of the photographic process itself.2 Chevrier’s opinion was published even before Wall’s return to black and white photography, which seemed to add further weight to his point, and also before Wall literally distinguished between ‘realism’ and ‘ambitious fantasies’ in his work, the latter rated by yet another writer as ‘mutually incompatible’.3 That said, there are also opposing views. Another essay, published in the same volume from 1995 that contains Chevrier’s piece, argues that Wall’s still lifes, although they appear remote from his more openly staged narratives, are ‘not so different’ after all.4 Adherents to both these positions can easily be found. Wall himself has both stated that his attitude towards photography was undergoing a change at that point, and, on other occasions, preferred to emphasize the coherence and continuity of his work; indeed he has sometimes argued both positions simultaneously.5 Consequently, Wall’s interviews are not a reliable source when it comes to the question of how viewers should construct artistic contexts for his different genres. As can be derived from what is suggested above, neither of the two perspectives is sufficient. Perhaps we should admit the instability of our attitude towards his varying approaches, and change our perspective accordingly, asking instead why it does not seem possible to arrive at an unambiguous interpretation of Wall’s overall ambition.

It is true, however, that Wall has decided at least once to reinvent his techniques and style, and the most promising way to answer our question is therefore to put some pressure on this most obvious shift in the artist’s aesthetic attitudes. In the light of this shift, the single print from Wall’s Landscape Manual marks only the latest step of a gradual process initiated when Wall started to reintegrate black and white photography in his production in 1996. Since then, documentary photography has occupied an important place in the artist’s work, and in his catalogue raisonné from 2005 a systematic division is made between cinematographic and documentary photographs, according to Wall’s own use of the terms. At the same time, the catalogue raisonneé shows that the shift cannot have signalled an ‘ontological turn’, as Michael Fried claimed some years ago.6 For, in retrospect, Wall ascribes the quality of the ‘documentary’ to transparencies that had been created years before he became involved in black and white photography again, and some of the pictures thus characterized might, if jugded according to how they look, easily pass as part of his cinema-based art. Others, though called ‘cinematographic’ in the catalogue entries, do not show any signs of narrative and visually might better fit with what we know as straight photography (Wall calls them cinematographic because some arrangement or posing took place before the shot). What is more, for Wall, black and white printing did not, and still does not, exclude staging and deliberate story-telling. The importance of the light-box, which initially contributed more to the cinematographic effects of his works than any of their other features, is certainly obscured by this shift, which has been criticized as a growing aesthetic conservatism on Wall’s part.7 An implicit confirmation of this view may be found, for example, in a recent essay on one of his less-frequently discussed transparencies. While dealing with the iconography of A Donkey in Blackpool from 1999, Steve Edwards hardly engages with the specifics of the photographic medium in this or any other picture by Wall.8 To judge by this, the medium-specific features of the illuminated box, once considered a critical contribution to enlightenment by the artist and by his commentators, and consequently placed in the forefront of its theoretical discussion, have lately become more marginal. This should not come as a surprise, representing, as it does, an effect of Wall’s own constant appeals to the legacy of European old master painting. His photograph of a donkey was produced for an exhibition for which contemporary artists had been asked to engage with an old master painting of their choice. In fact, Wall might be said to think of almost his entire oeuvre in terms of such possible or actual gallery encounters, and so as obliged to pursue attention-seeking strategies along the lines of those nineteenth-century painters who had to secure a high visual profile for their works when it came to the annual public salons. The assistance given by transparencies in this respect should not be ignored. Electric illumination cannot be regarded unequivocally as a critical tool once the works become integrated into the canon of art. However, Wall himself has recently been downgrading the pre-eminence of the backlit image, occasionally at least, by way of his interest in traditional photographic printmaking. As such it becomes more important to ask why he is continuously pursuing both tracks, notoriously referring, on the one hand, to sources from Brueghel and Caravaggio via Poussin and Chardin to Delacroix and Manet, while, on the other hand, evoking the traditions of narrative cinema and straight documentary photography alike.

Admittedly, Wall’s manner of self-fashioning has perhaps slightly shifted over time. While the artist argued early on in his career that he had never seen himself as a photographer, he stressed on a later occasion that he has always practised ‘straight photography’ along with ‘cinematography’, and that he considers both ‘equally legitimate’. This is, of course, Wall’s perogrative, but it is not clear from these statements whether the legitimacy of both strategies is based on acknowledging their respective features and aims. Although Wall recognizes ‘photography’s unique properties’, he does not see any conceptual conflict between cinematography and reportage, and does not acknowledge a sharp opposition between ‘reportage’ or ‘documentary’ on the one hand, and ‘fiction’ on the other.9 As a consequence, the terms no longer point to a distinctive programmatic commitment. Just as one might be surprised to note that Wall does not accept a clear distinction between the different style and medium concepts on which he has based his work, one might also feel puzzled by this amalgamation of traditional genre categories. But there is one perspective from which it does make sense. All we need to forget is that the ‘documentary’ is usually understood as a visual genre with specific characteristics, including the implication that the photographer is operating in a non-artistic way. Wall, however, considers the term from the perspective of the artist’s relation to his medium, thereby conflating its concerns with those of artistic style. He adheres to straight photography’s outright identification with the documentary, and thus takes up the problem where Walker Evans left off. Evans had become involved in documentary campaigns in the 1930s, and had produced his most compelling pictures in this context, self-reflective as his aesthetic approach had been at the time. In his later years, however, Evans argued that art can never be a document but has the ability to adopt its style, thereby expunging the thin line that separated his early work from fine art. Wall, in turn, has never allowed any doubt that he acts within the boundaries of the artworld, and his concept of the documentary is much less close to Evans’ early practice than to his famous last formulation.10 In Wall’s terms, the documentary is again a matter of style, and ‘near documentary’ may be translated as a contemporary version of traditional realism, supported by the truth claims of the photographic. Ultimately, we can take Wall’s use of the term documentary as a means of reinforcing what a commitment to realism used to express when styles were taken as a statement of aesthetic beliefs. Wall is still a ‘realist’, even if a less straightforward one than Evans.

In light of this, it comes as no surprise that Evans, as a documentary photographer, is among the forerunners claimed by Wall for his own large-scale depictions of modern life. When Wall looks back at his earlier aesthetic experiences in a text of 2003, he gives a very idiosyncratic interpretation of Sherrie Levine’s notorious appropriation of several venerable masterpieces of straight photography, interpreting her strategy as a homage to the value of the masters, which he presents as unsurpassed and lasting. In fact, he takes Levine’s appropriations as an attempt to identify with the practices cited rather than with the practice of citation itself. Even if Wall were stimulated by Levine’s own earlier complaints about critics who avoided ‘looking at the work, looking inside the frame’, his view of her work obviously departs from what is usually accepted as Levine’s postmodernist formation.11 However, let us assume for a moment that this view is persuasive, and get back to his puzzling After Landscape Manual, which I discussed at the outset. Levine’s prints had been entitled After Edward Weston, After Walker Evans, and After Alexander Rodchenko. Should we therefore feel invited to see Wall’s revision of his own earlier original in the same light as his remarks on Levine? Does Wall bow in the face of his own early photography’s uncorrupted, straight gaze? Is his picture, in its present guise, an attempt to save from the shipwreck of conceptual art those things that are still valid today? Or is he merely offering a nostalgic citation of what was once a genuine aesthetic experience? In sum, the question is whether Wall’s picture is a view in its present guise, or a view of a view. The title implies the latter, especially if we recall Levine’s position in the theoretical framework of postmodernism. If, however, we take it as an allusion to Wall’s appraisal of her achievement, it implies the contrary, and I tend to the second option. But the question is further complicated because the original source is excluded by Wall from his catalogue raisonneé as if to obscure the fact that the picture had its roots within a different framework.12 If Wall’s version was intended as a celebration of the original, why was the original then neglected in the list of works? In fact, the print’s title gives it an almost Hegelian touch: this photograph abolishes, preserves, and elevates conceptual photography in a single gesture. In this respect, After Landscape Manual is the perfect emblem of Wall’s perspective on photography after conceptual art and, so to speak, after Sherrie Levine. The artistic gesture of self-appropriation turns out to carry a very high significance. The picture itself, however, has not become more complex as a result of its post-conceptual afterlife. We have to be aware that Wall’s afterthoughts on conceptual photography are as partial as the framed view from his car. They are designed to invest his later practice with the legitimacy of an heir to the very essence of photography. At the end of his long discussion of photography’s passage through modernism, Wall concludes that what the medium promises to its audience is an ‘experience of experience’.13 Apparently, he intends by this to defend photography from Theodor W. Adorno’s verdict that truly modern art memorializes the absence of genuine experience under the conditions of modernity. It is obviously not easy to explain how photography, as an art form, can offer direct access to authentic experience if painting cannot. Wall probably feels compelled to distinguish between the two media in order to to give photography a history in its own right, and to grant distinct tasks and legitimate claims to painting and photography as separate genres.14 But it seems that, in this respect, he goes too far. And if we disburden the phrase of its self-reflective twist, flamboyant yet unfathomable at this point in Wall’s argument, we find ourselves confronted with a quite traditional celebration of photography’s connection to the experience of the world outside art. Wall would probably not deny that. When it comes to discussions of photography’s medium specificities in his writings and interviews, he tends to grant it a privileged contact with reality. The isolation of After Landscape Manual from the Landscape Manual itself confirms this tendency, as it eliminates the text, and thus cuts off the context that had once mediated experience; it offers the experience of a view without the distanciating effect of Wall’s comments.

3 Jeff Wall, Concrete Ball, 2002. Transparency in light-box, 204 × 260 cm. New York: Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Courtesy of Jeff Wall and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

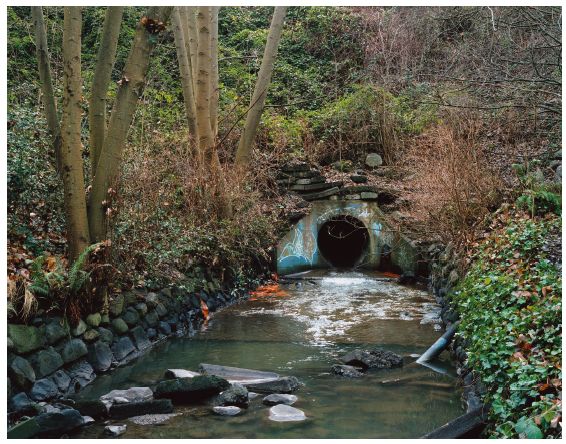

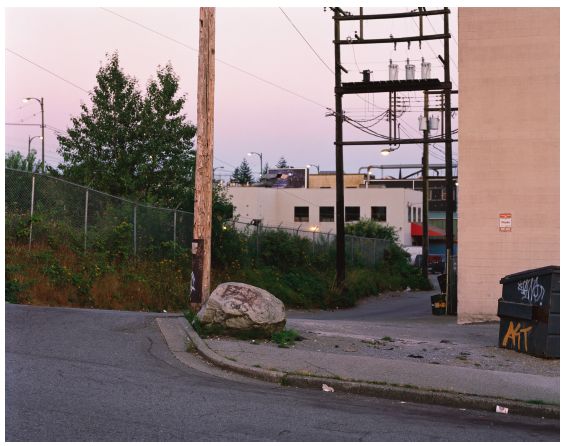

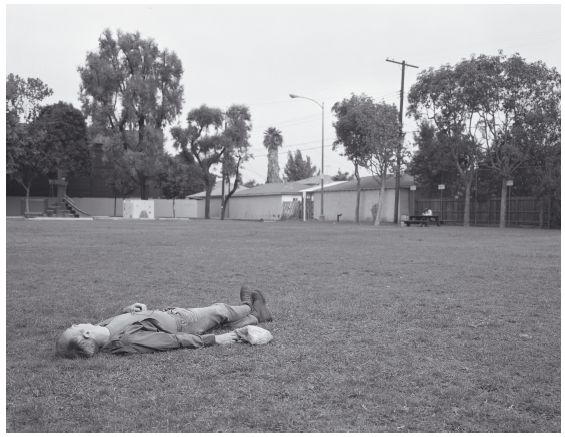

A similar strategy of offering space for the viewer’s private imaginative projection can be found in Wall’s landscapes and related subjects. Some of his more recent cityscapes, interiors and landscapes look like empty stages, ready to receive performances (plate 3). At any rate, this is what several authors have declared, and we may feel inclined to make this perspective our own. But what makes us think that we get it right if we subscribe to this idea, suggestive as it is? It is worth remembering that allegorical readings of this kind have not always been taken for granted by photography critics. In a generally negative review written on the occasion of an Edward Weston exhibition in 1946, Clement Greenberg surprisingly praised several photographs of painted Hollywood ‘ghost sets’15 (plate 4). Given Weston’s play with layers of reality in these unusual pictures, it is certainly appropriate to single them out among his works. And yet Greenberg, his predilection for documentary photography notwithstanding, did not point to the disturbing fact that he was looking at the unmasked backgrounds for the staging of films. Rather, he felt attracted by the stylistic unity of the picture surface: nothing ghostly about the sets, according to him. Conversely, Eugene Atget’s more famous pictures of lifeless Parisian streets had once been conceptualized by the artist as plain documents, as reference material, and they became stages for implied narratives – for crime scenes, as Walter Benjamin was to put it – only once writers or artists annexed them for their own imaginary purposes later on.16 The evidence of Wall’s individual pictures is arguably not decisive in this respect. While his silent streets and landscapes are certainly very evocative in some ways, this is not necessarily because of any particular intrinsic narrative feature. If you are, for example, ready to imagine events on the site of Wall’s Still Creek of 2003, you may have been prepared by The Drain, which depicted the same location as a background for a staged situation in 1989 (plates 5 and 6). While this is, admittedly, an exceptional example of a revised set, we can nevertheless see its effect as revelatory in general terms. When working on a photograph in 2001 that had originally been conceived cinematographically, Wall introduced a sense of suspended narration by deciding to delete the figures from the foreground, as though cancelling a scheduled stage performance17 (plate 7). The effect of the picture’s title thus made nature the main actor in an otherwise boring commercial district. But this rosy dawn is not enough to keep the phantasy of its viewers occupied. They are likely to wonder why this site was depicted at all. They might guess that Atget had influenced Wall at that time, and project onto Wall’s images what was previously said by critics of Atget’s empty street scenes (plate 8). Induced by their knowledge of the more explicit encounter with the cinema in Wall’s earlier work, they might also recall establishing shots in feature films, allowing countless fragmentary narratives to be engendered. Chevrier confirms as much when he claims that the view reminds him of’pictures of ambiguous urban encounters’, while Camiel van Winkel described a similar impression from one of Wall’s earlier documentary interiors when he argued that, even after the removal of all the props from the depicted room, some ‘artificial reality’ dominates the scene.18 I do not want to deny the possibility of such a reading. It is true that Wall’s documentary pictures frequently retain narrative aspects introduced by their cinematographic counterparts, and vice versa.19 But this is neither the exclusive result of their own internal arrangement, nor of any specificity of the medium. An essay by Thierry de Duve implicitly suggests another explanation. De Duve manipulated The Drain – though only in his imagination – when he suggested to his readers that they substract the figures from the middleground of Wall’s scene. In the critic’s eyes, however, this imaginative experiment did not enhance the documentary value of the landscape. On the contrary, de Duve thereby discovered a landscape that reminded him so strongly of Cézanne that in his subsequent remarks he came close to describing it as an abstract composition.20 With de Duve’s somewhat surprising interpretative process and its results in mind, I want to suggest that the production of meaning in Wall’s documentary pictures is dependent upon the transport of interpretative models from one genre to another. Furthermore, it is the result of a deliberate contextualization in artistic tradition, first and foremost admidst his own pictorial contributions. It is, in other words, the documentary pictures’ place in Wall’s own oeuvre that adds meaning to their form and content, and Wall may well have aimed at putting the rule to the test when he photographed Still Creek, in which de Duve’s suggestion seems to resonate, yet without effectively resulting in abstraction. Confirmation can also be found in an essay by Chevrier where it is argued that Wall’s Citizen, while imitating a snapshot through careful arrangement, is in fact an image of civic peace rather than ‘an image of leisure time in the park’ (plate 9). The very structure of this argument, however, precludes us from finding its basis in the picture itself. If we want to find civic peace here, we must first grasp an allegorical vocabulary, which is not consonant with the look of a snapshot however artificially it might be achieved. Chevrier seems to be aware of this fact. In order to explain his reading, he puts himself in the place of the depicted person, and imagines that the public space of the park may be experienced as a refuge from the social violence that is frequently shown in Wall’s earlier work.21 Convincing or not in terms of the picture’s narrative, this approach gives a reading of photography against the grain: uncodified everyday reality, as supposedly recorded by the medium, cannot be taken as the basis of the kind of meaning an allegorical interpretation would claim to find in the work.

4 Edward Weston, Movie set [Twentieth Century Fox; pool hall], 1940. Black and white photograph, 19.2 × 24.4 cm. Tucson, AZ: Center for Creative Photography. Photo: Courtesy of Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona.

5 Jeff Wall, Still Creek, Vancouver, Winter 2003, 2003. Transparency in light-box, 202.5 × 259.5 cm. Photo: Courtesy of Jeff Wall and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

6 Jeff Wall, The Drain, 1989. Transparency in light-box, 229 × 179 cm. Düsseldorf: Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen. Photo: Courtesy of Jeff Wall and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

7 Jeff Wall, Dawn, 2001. Transparency in light-box, 230 × 293 cm. Zurich: Collection Ringier. Photo: Courtesy of Jeff Wall and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

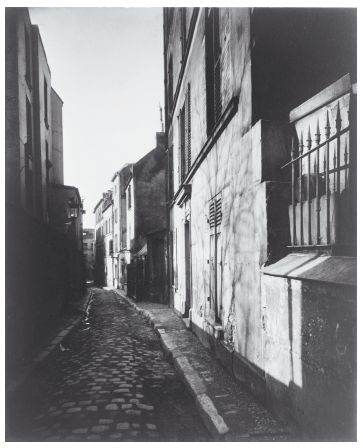

8 Eugene Atget, Rue St. Rustique, 1922. Toned gelatin silver print, 21.7 × 17.5 cm. Washington, DC: Library of Congress. Photo: Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

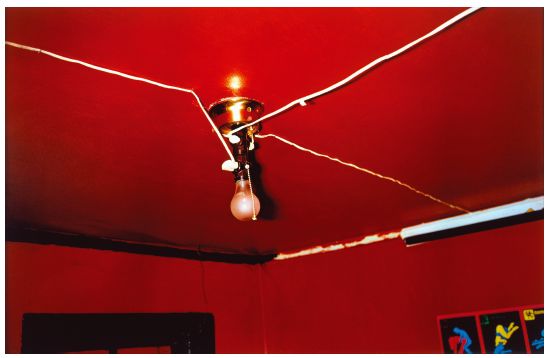

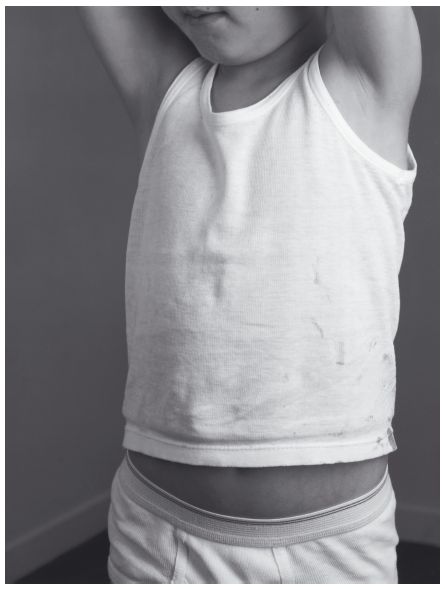

At the beginning of this chapter, I evoked an audience accustomed to deciphering the meaning of pictures. We are, and yet we are not, such an audience. Decades of exposure to the plainest, most ostentiously meaningless documentary pictures in the artworld have prepared us for the absence of depth and complexity deliberately adopted by some artists. Yet there is evidence from the critical texts I have discussed that this condition does not apply without qualification to our response to Wall. The more his work develops, the harder it becomes for viewers to escape the codified network of meanings that he has established for it. His oeuvre as a whole tends to build up an inclusive reference system that underlies each of the individual works, their splendid isolation on museum walls notwithstanding. It does not do so exclusively by referring to the old masters of Western painting. What is more, the range of traditions becomes internalized, as it were, in Wall’s work as it embodies a whole revitalized history of photographic concepts. Atget and Evans provide the most prominent paradigms in this respect, but theirs are not the only ones. Take, for example, Wall’s pictures of interior structures and his diagonal compositions. They are partly modernist in their formalistic approach, and, if references need to be named, the avant-garde photography of the 1920s would be a candidate alongside William Eggleston’s obsession with colour effects in vernacular architecture (plates 10 and 11). Eggleston, of course, is also a precursor of Wall’s Peas and Sauce still life, which brings us back to reportage photography effects. But there are also references to a more classical concept in some of Wall’s black and white pictures. In his Shapes on a Tree from 1998, concerns with the structure of nature’s surface remind us of Weston, and so does the cropping of Wall’s Torso from 1997 which seems to echo Weston’s series of his son Neil’s torso from 1925 (plate 12). Weston was always in search of formulae for beauty in photography, and harked back to the set phrases of classical art in order to achieve them.22 Consequently, he might be considered an inappropriate model for an artist who has continuously stressed his preoccupation with the depiction of modern life. What is more, Wall has acknowledged that he is familiar with Greenberg’s polemic against Weston, who, in the eyes of this critic, had lost his way by attempting to align his pictures with the aesthetics of modernist abstraction.23 Yet it seems that Wall is interested in precisely this matter. Although de Duve has convincingly argued that Wall’s confirmed interest in Greenberg’s text can be explained by their shared belief in photography’s material and ideological transparency, a different explanation needs to be found for his return to modernist photography of the kind explored by Weston several decades ago. Wall’s Shapes on a Tree is arguably a picture concerned with the very formal values, structural and tonal alike, that had so horrified Greenberg in Weston’s prints. If Weston’s idiom does indeed provide another context when adopted by Wall, this is due to our preconception, based on Wall’s work as a whole, that he is interested in giving it a realistic bias.

9 Jeff Wall, Citizen, 1996. Silver gelatine print, 181 × 234 cm. Montréal: Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal. Photo: Courtesy of Jeff Wall and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

10 Jeff Wall, A Wall in a Former Bakery, 2003. Transparency in light-box, 119 × 151 cm. New York: Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Courtesy of Jeff Wall and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

11 William Eggleston, Untitled (Red Ceiling, Greenwood, Mississippi, 1973). Dye transfer print, 20 × 24 cm. Photo: © 2007 Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy of Cheim and Read, New York. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

Again, this is a realism that has nothing to do with the world’s spontanously depicting itself. A second glance at Wall’s Torso reaffirms the point. In my view, the most attractive feature of the picture is the dirt on the shirt of the little boy. At first sight, I liked it as much as Camille Recht, who, evoking early photography in an essay on Atget, once said he liked the dirt on the shoes of an unknown peasant on an old professional studio portrait.24 He saw in that staged photograph a richer dust than any other medium could provide, trusting that a trace of reality had been retained in the print. My feelings seemed to be of nearly the same kind when I compared Wall’s Torso with his other works, including his studies after nature, and for a moment I wondered if I were being exposed to a sensation best explained in terms of Roland Barthes’ much-cited ‘punctum’. However, I soon gave up this idea, as the deliberate composition made it seem unlikely that anything had got into this picture by accident. Consequently, I do not suscribe to Craig Burnett’s belief that this composition can appropriately be called a documentary, let alone a sketchy picture. In his catalogue raisonné, Wall calls it ‘cinematographic’, and there can be no doubt that he cared for the stains more than the anonymous studio photographer had done when he portrayed the peasant so long ago.25 Wall may have been well aware of the possibility of reading this image as an ironic counter to Weston, that is, an evocation of beauty in the everyday that advances a kitchen- sink realism against neo-classicist aesthetics. Yet though the tastes of the artists apparently differ, it is important to note the strategic relevance of such dialogues. Photography attains the same level of formal ambition as the traditional arts, whatever the actual relation of the individual pictures to their sources might be. Wall’s black and white prints can, for the same reason, profit from cinema, neo-avant-garde, and the Western pictorial tradition built into his ‘cinematography’ no less than his transparencies, which compete more obviously with traditional values. His prints thereby help to pave the way for a pictorial art that may, as Wall puts it, ‘include both fact and artifice, tradition and the new, memory and new technologies’.26 At the same time, the photographic connection of his transparencies with the real world is confirmed by their increasingly being merged with the documentary tradition, reinforced by Wall’s blurring of the categorial boundaries between the two kinds of picture-making. Accordingly, we are confronted with an enormous appetite for references even in Wall’s straight photography. All this taken into account, Wall reminds me of a character invented by the Austrian writer Heimito von Doderer for his novel The Merovingians or the Total Family of 1962. Very loosely based on the personality of a medieval king, but transferred to the twentieth century, this character, who seeks to increase his sovereign power, attempts to become his own father and grandfather, his nephew and uncle, and more of the kind, by a sequence of strategically planned marriages to, and adoptions of, members of his family, thus uniting under one roof as many heritages and fiefdoms as possible. I do not want you to take this comparison as my attempt to ridicule Wall’s serious endeavour to draw inspiration from the traditions of Western art. Yet his attitude towards art history – Merovingian in Doderer’s terms – might indeed be driven by similar aims.27 After Landscape Manual, which I chose as the primary example for this chapter because it demonstrates Wall’s ambiguous reconciliation with his own conceptualism’s claim on the documentary, is only the latest in a long line of attempts to make his work a repository of complex meaning as defined by the overlapping discourses of art, art criticism, and the historiography of art.

12 Jeff Wall, Torso, 1997. Silver gelatine print, 24.5 × 19.1 cm. Edition for documenta X. Photo: Courtesy of Jeff Wall and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

We might at first assume that the more an artist draws from a wide range of stylistic sources and genres, the more his work will become polysemic and inconsistent. Complex anti-systematic aesthetic strategies can be nourished thus. In the case of Wall, however, enlarging the network of references and – more importantly – of processes and techniques is about cluster-building and consolidation. Wall’s Storyteller is arguably not much closer to édouard Manet than the latter’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe was to Marcantonio Raimondi’s sixteenth-century Judgement of Paris engraving, which had served as a model for Manet’s own composition of figures. Nor is Manet close to other painters cited in Wall’s work. Such widespread references make sense only because what Wall wants to mirror is the wordly, and supposedly subversive, character of their pictures. In doing so, he is mainly responding to conceptions of reality found in contemporary discussions of the social meaning of images.28 Consequently, nearly the entire tradition of narrative Western painting is synthesized in a practice that wants to be read in terms of realistic style, while at the same time this realism is premised on the causal dependence of photography on the world. Wall thus merges style and medium in a remarkable move. To reiterate, why did it become necessary? The exploration of documentary trends in some of Wall’s works testifies to an assumption that art photography connects with the outer world, and without this asumption his overall aims lose some of their authority. Having said this, there is no evidence of a ‘system of photography’ in Wall’s work that keeps it devel- oping.29 Rather than following Shepherd Steiner in that argument, which gives all the credit to the logic inherent to a single aesthetic concept, we should posit, as one basis for the artist’s deliberate changes and revisions, his wish to associate additional layers of meaning and relevance with his work. From this perspective, there is neither a simple pairing of different aims, nor a change of beliefs, but rather the increasing density of an oeuvre that struggles for sustainability in the developing discourse. Wall wants each individual part of it to be understood in the light of what the others have achieved in his own eyes and those of his commentators. Hence, that Wall adheres to the integrative identity of his oeuvre, meandering through genres and art history as it does, can be read as a coherent position. In a conversation with Chevrier, Wall declared that he would appreciate seeing his black and white pictures exhibited alongside his grotesque imagery, arguing that the fact that both are photographs subliminally connects the two groups of works.30 As a matter of fact, such very different approaches need each other in order to meet their author’s desire to give his pictures a complex meaning and critical contemporaneity alike. Wall wants them to show codified gestures and the autonomy of art on the one hand, and reality and the constraints of social forces on the other. He ascribes to them the power simultaneously to express the individual freedom of the artist as well as the accidents of the outer world and, particularly in his colour transparencies, the subtle and sophisticated impact of uncontrolled facts on pictures that are obviously artificially staged.31 In 1995, Wall described the tension between form and content as a record ‘of our social experience of tormented development, that which is not achieved or realized, or that which, in being realized, is ruined – and also all the unresolved grey areas in between where hope and alternatives reside’.32 To make this evident is not an easy task, and it is possible that Wall has some doubts today whether his art can achieve this goal. Yet at a time when he did univocally associate his pictures with it, while probably questioning the possibility that any single pictorial code or framework could bear this burden in isolation, his strategy was a continuous extension of coherent conceptual devices. Since then, we have witnessed an increasing breadth of perspectives, styles and genres in Wall’s works. In them, I tend to see neither a development according to a consistent programme, nor monads that express unity and completeness without mutually affecting each other. Rather, we should understand that an extrinsic discourse on art history in general affects it, and that our voices intermingle with the artist’s in his work. This does not necessarily mean that he is obedient in any way to the arguments of his supporters and adversaries. It does mean, however, that variations in his methods, in his motifs, and in his use of the medium might be best understood as continuous footnotes, glosses, and exemplifications of conceptual claims, driven by an ongoing debate on the meanings and the value of reality and realism in art. It is only ‘after cinematography’, and against its backdrop, that a reading that finds the very image of civic peace in the photograph of a sleeping man can hope to make sense.

Notes

1 Jeff Wall, “‘Marks of indifference”: aspects of photography in, or as, conceptual art’, in Ann Goldstein and Anne Rorimer, eds, Reconsidering the Object of Art, 1965–1975, Los Angeles, CA, 1995, 247–67, 254. See, on the relevance of Ruscha and Smithson for the Landscape Manual, and on the latter’s concept, Scott Watson, ‘Discovering the defeatured landscape’, in Stan Douglas, ed., Vancouver Anthology: The Institutional Politics of Art, Vancouver, 1991, 24765, 252–3.

2 Jean-François Chevrier, ‘Play, drama, enigma’, Jeff Wall, Chicago, IL, 1995, 11–16, 12.

3 Peter Galassi, ‘Unorthodox’, in Galassi and Neal Benezra, Jeff Wall, New York, 2007, 13–65, 52.

4 Briony Fer, ‘The space of anxiety’, in Jeff Wall, 1995, 23–6, 25.

5 When talking to Boris Groys, ‘Photography and strategies of the avant-garde’ [1998], in Rolf Lauter, ed., Jeff Wall. Figures and Places: Selected Works 1978–2000, München, 2001, 138–41, 138, Wall described his changing relation to photography. In an interview with Arielle Pelenc, ‘Correspondence with Jeff Wall’ [1996], in Thierry de Duve et al., Jeff Wall, 2nd edn, revised and expanded, London, 2002, 8–23, 13, he described his ‘phantasy pictures’ as an extension of what had always been present. In another interview with Martin Schwander, ‘Jeff Wall interviewed by Martin Schwander’, in Schwander, ed., Restoration, Basel, 1994, 22–30, 29, he argued that he followed simultaneously different paths.

6 Michael Fried, ‘Being there: on two Pictures by Jeff Wall’, Artforum, 43,1, 2004, 53–4, 53.

7 Sven Lütticken, ‘The story of art according to Jeff Wall’, Secret Publicity: Essays on Contemporary Art, Rotterdam, 2006, 69–82, passim, esp. 77, where the disappearance of critical comments on mass media from Wall’s work is subject to a disparaging review.

8 See Steve Edwards, “‘Poor ass!” (A Donkey in Blackpool, 1999)’, Oxford Art Journal, 30,1, 2007, 39–54. Replace, in his text, each occurrence of the word ‘photograph’ by ‘picture’, and each occurrence of ‘photographer’ by ‘picture-maker’. Neither any alteration of the meaning nor any obscurity will result from doing so.

9 Pelenc, ‘Correspondence’, 9 and 23 (for the first set of terms), and Wall’s letter to Christine Walter from May 2000, cited by her in Bilder erzahlen! Positionen inszenierter Fotografie: Eileen Cowin, Jeff Wall, Cindy Sherman, Anna Gaskell, Sharon Lockhart, Tracey Moffatt, Sam Taylor-Wood, Weimar, 2002,122 (for the second set): ‘Photography exists in the interaction between those qualities, which are always present somehow, in every photograph.’

10 For a discussion of Evans’ retrospective response to his own work, see Wolfgang Bruckle, ‘On documentary style: “anti-graphic photography” between the wars’, History of Photography, 30, 1, 2006, 68–79, esp. 79. On Wall’s ‘non-medium specific conception of the pictorial’, see Diarmuid Costello, ‘On the very idea of a specific medium: Michael Fried and Stanley Cavell on painting and photography as arts’, Critical Inquiry, 34, 2008, 274–312, 299–300, where the issue is considered from a systematic point of view.

11 Jeff Wall, ‘Frames of reference’, Artforum, 42, 1, 2003, 188–92, 188. For Levine’s statement, cf. Gerald Marzorati, ‘Art in the (re)making’, Artnews, 85, 5, 1986, 91–9, 97.

12 See Theodora Vischer and Heidi Naef, eds, Jeff Wall: Catalogue raisonné, 1978–2004, Göttingen, 2005, cat.-no. 118, 428–9, where a description of the Landscape Manual is given, without, however, allowing it to enter the body of work as defined by the catalogue entries. Wall is certainly aware of the context-making effects provoked by this strategy of exclusion. His training as an art historian is no doubt important in this respect. At the same time, it should be noted that his shaping of his oeuvre’s boundaries is in line with the self-indexing activities of some of his colleagues. See, for a general account of this contemporary tendency, Peter J. Schneemann, ‘Eigennutz: Das Interesse von Künstlern am Werkkatalog’, Zeitschrift fur Schweizerische Arch- ologie und Kunstgeschichte, 62, 2005, 217–23.

13 Wall, “‘Marks of indifference”’, 266.

14 While the ‘experience of experience’ might also be understood in Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel’s or Hans Georg Gadamer’s terms, it is likely that in this context it is meant to evoke Adorno. This becomes obvious when the term is read against the background of Wall’s own earlier ‘Note on movie audience’, which was written to accompany an exhibition of his works. Here Wall not only claims that ‘the modernist image is knowingly experienced as an experience of estrangement’, but also mentions the ‘culture industry’ in the same paragraph. See Jeff Wall, ‘A note on movie audience’ [1984], Jeff Wall: Catalogue raisonne’, 280–2, 280 and 281, and Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory [1970], newly trans. and ed. by Robert Hullot-Kentor, London, 1997, 34 and passim (esp. 110–1, 333). Watson, ‘Defeatured landscape’, 257, makes the point that in his Landscape Manual, Wall displayed the failure to establish an authentic relation to the reality of experience. If this was the lesson Wall wanted his audience to learn from his early work, his perspective obviously was to change.

15 See Clement Greenberg, ‘The camera’s glass eye: review of an exhibition of Edward Weston’ [1946], Arrogant Purpose, 1945–1949 (The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 2), ed. John O’Brien, Chicago, IL and London, 1986, 60–3, 63.

16 Walter Benjamin, ‘Little history of photography’, Selected Writings, ed. Michael W. Jennings, vol. 2 (1927–1934), Cambridge and London, 1999, 507–30, 527. It should be noted that the term, albeit usually credited to Benjamin, actually derives from Camille Recht, who, in his introduction to Atget Lichtbilder, Paris and Leipzig, 1930, n.p., 5–28, 15, drew the comparison with a ‘Polizeiphotographie am Tatort’. However, it was Benjamin who turned the metaphor into a theoretical device.

17 Wall’s commentary in Jean-Pierre Criqui, ‘Interview with Jeff Wall’, in Correspondances: Jeff Wall/ Paul Ce’zanne, Paris, 2006, 30–53, 31, in which the artist also admits that he was impressed by Atget’s work at that time.

18 See Jean-Francois Chevrier, ‘The spectres of the everyday’, in Jeff Wall, 2002, 164–89, 188, and Camiel van Winkel, ‘Jeff Wall: photography as proof of photography’, in Hasselblad Center Göteborg, ed., Jeff Wall: Photographs, Göttingen, 2002, n.p., 7–13, 12.

19 Criqui, ‘Interview with Jeff Wall’, 36.

20 See Thierry De Duve, ‘The mainstream and the crooked path’, in Jeff Wall, 2002, 26–55, 36.

21 See Chevrier, ‘Spectres’, 169–73. Chevrier also argues that The Well was taken up again metaphorically in An Encounter in the Calle Valentin Gomez Farias, Tijuana, and was brought to a culmination with the recent sumptuous Flooded Grave, thus making a point that is not in line with his previous characterization of the oeuvre as an assembly of isolated programmes.

22 The very idea of the torso as a repository for beauty is, of course, neo-classical, and became a support for formalistic preoccupations in modernist art. John Szarkowski’s remarks on a Weston ‘Torso of Neil’ from 1925 in his Looking at Photographs: 100 Pictures from the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1973, 84, are symptomatic in this respect. (More examples from the same series are reproduced in Gilles Mora, ed., Edward Weston: Forms of Passion, Passion of Forms, London, 1995, 102–3, and in Elena Lukaszewicz, ed., Edward Weston, Manchester, 1998, 20.) For a more general discussion, see Katrin Elvers-Svamberk, ‘Von Rodin bis Baselitz: Der Torso in der Skulptur der Moderne’, in Elvers-Švamberk and Wolfgang Brückle, Von Rodin bis Baselitz: Der Torso in der Skulptur der Moderne, Ostfildern-Ruit, 2001,13-84.

23 Wall’s knowledge of the Greenberg text is reported by De Duve, ‘The mainstream’, 28–9.

24 Recht, Atget, n.p., 11.

25 Craig Burnett, ‘Jeff Wall: black and white photographs 1996-2007’, in Jeff Wall: Black and White Photographs, 1996–2007, London, 2007, n.p., 51–60, 51, and Jeff Wall. Catalogue Raisonné, cat.-no. 75, 382.

26 Wall in a letter to Christine Walter from May 2000, cited by Walter, Bilder erzählen!, 113.

27 In this respect, his most expansive figure of aesthetic thinking is probably his argument regarding the issue of scale, which leads him to imagine a viewer of Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (and, by implication, of his own large-scale pictures) standing on a Carl Andre sculpture. Cf. Wall, ‘Frames of reference’, 191.

28 Thomas Crow, ‘Profane illuminations: the social history of Jeff Wall’, Art Forum, 31:6,1993, 62–9, gives an overview of Wall’s keeping pace with the course of social art history in the 1970s. Interestingly, Wall has been involved in this discourse from his early comments on Manet onwards, and defines traditions in written form himself where professional art historical writing fails to find meaning in the combination of the models he refers to in his artistic decision-making: cf. Wall, ‘Frames of reference’, where the documentary and the fictional are, once again, guided to a marriage of true minds.

29 Shepherd Steiner, ‘In other hands: Jeff Wall’s Beispiel’, Oxford Art Journal, 30, 1, 2007, 135–51, 151, where the opposite view is advanced.

30 Jeff Wall and Jean-Francois Chevrier, ‘A painter of modern life’ [i.e. ‘At home at elsewhere’, 1998/ 2001], in Jeff Wall: Figures and Places, 168–85, 182. Wall’s black and white prints were actually shown in rooms of their own in the 2005 exhibitions at the Schaulager Basel and at the Tate Modern.

31 See Pelenc, ‘Correspondance’, 17 and 22, and Groys, ‘Photography’, 152–4.

32 Jeff Wall, ‘About making landscapes’ [1996], in Jeff Wall, 2002, 140–5, 144.