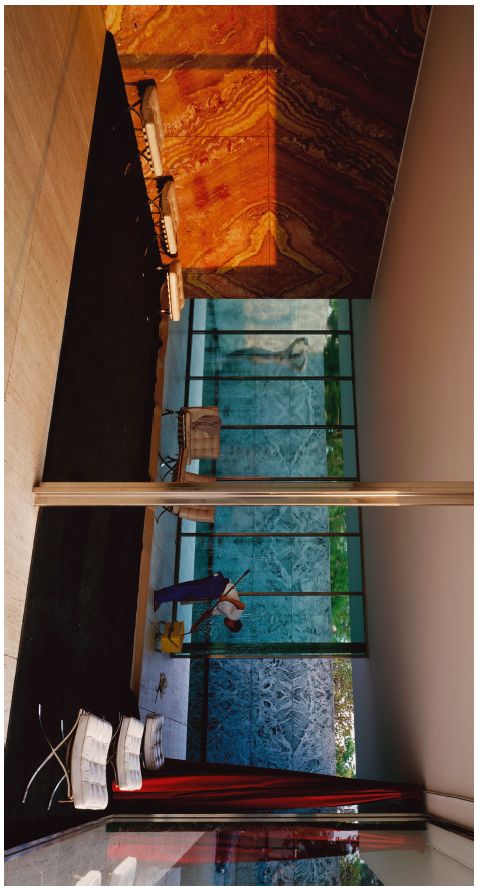

1 Jeff Wall, Morning Cleaning, Mies van der Rohe Foundation, Barcelona, 1999. Transparency in light-box, 187 × 351 cm. Photo: © Jeff Wallm

.

10

MORNING CLEANING: JEFF WALL AND THE LARGE GLASS

Jeff Wall’s Morning Cleaning, Mies van derRohe Foundation, Barcelona, 1999 (plate 1), is a photographic tableau characteristic of his practice since the early 1990s. It is a large format Cibachrome transparency, mounted on a light-box and employing digital technology to suture a montage of images into the seamless appearance of captured reality. The scene is the reconstruction, completed in 1986, of the much celebrated German National Pavilion, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona, and widely recognized as a pivotal example of modernist architecture. The ostensible subject is the morning ritual of cleaning the wide expanse of metal-framed glass that separates the interior of the pavilion from the transitional space of the courtyard with its reflecting pool. Through a film of soapy water we see Georg Kolbe’s bronze sculpture Dawn,1 poised at the far left of the pool and illuminated, like the interior wall of onyx doré, by the early morning sunlight that Wall recalls was optimal for a mere seven minute interval during each of the twelve or more days required to photograph this space.2

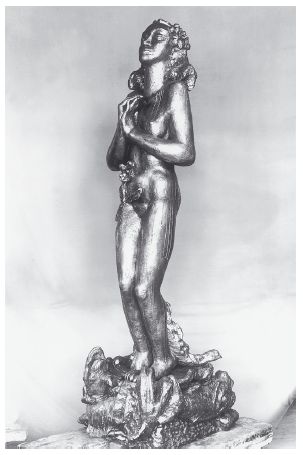

Penelope Curtis tells us that Mies used the figurative sculptures of Kolbe, along with those of Wilhelm Lehmbruck and Aristide Maillol, almost exclusively throughout his career, their curvaceous forms contrasting with the unadorned linearity of his designs. She uses the term ‘eye-catcher’ to account for the way in which Kolbe’s Dawn extends our view through the glass to the pool beyond with its green marble walls, much like a ruin in a picturesque landscape.3 Indeed, as can be seen in a Berliner Bild-Bericht photograph of the German Pavilion of 1929 (plate 2), the more than life-size figure of Dawn acts as a beacon to orient the viewer in relation to the pavilion’s bewildering flow of transitional and overlapping spaces, multiply reflected in Mies’s luxuriant surfaces of honed marble and glass.

But Dawn does not catch the eye of the window-cleaner, who remains oblivious to the allure of the Venus-like figure rising to meet the morning light, opening outwards in a ‘centrifugal’ unfolding, ‘rippling in a manner suggestive of the pool where it stands’, writes Curtis.4 The veil of soapy water also ripples and blurs in ways that suggest a figure in suspended animation, creating an ambiguity between the animate and the inanimate that is, in a word, uncanny. However, the window-cleaner Alejandro – for elsewhere, Wall tells us his name5 – is turned away from this erotic vision, bent intently over his bucket, preparing his squeegee before removing the soapy screen. At the same time, he is equally oblivious to the gaze of the spectator.

2 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (architect), Williams & Meyer Co. (photographic studio), Exterior view of the German Pavilion at the Barcelona International Exposition of 1929–30, Spain, with Georg Kolbe’s bronze sculpture Dawn. Gelatine silver print, 16.6 × 22.3 cm. Montreal: Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture (Gift of Edward Austin Duckett). Photo: © CCA, Montréal/Lohan Associates/DACS, 2009.

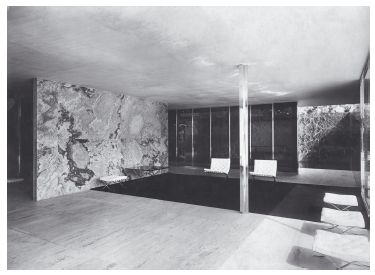

3 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Interior view of the German Pavilion at the Barcelona International Exposition of 1929–30, Spain. Gelatine silver print, 16.5 × 22.5 cm. New York: Mies van der Rohe Archive, Museum of Modern Art (Gift of the architect, MMA 1814). Photo: © The Museum of Modern Art/SCALA/ARS, NY (2009)/DACS, 2009.

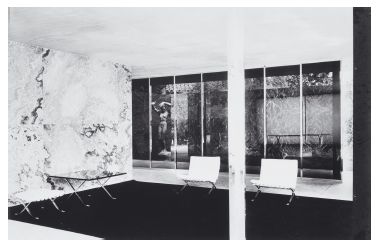

4 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (architect), Williams & Meyer Co. (photographic studio), Interior view of the German Pavilion at the Barcelona International Exposition, 1929–30, Barcelona, Spain. Gelatine silver print, 15.2 × 23.5 cm. Montre´al: Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture (Gift of Edward Austin Duckett). Photo: r CCA, Montre´al/Lohan Associates/DACS, 2009.

It is this absorption in the task at hand that interests Michael Fried in his essay ‘Jeff Wall, Wittgenstein, and the everyday’, published in Critical Inquiry in 2007 and reprised in Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before in 2008. In a careful unpacking of passages from Wittgenstein’s notebooks of 1930, Fried argues for the philosopher’s ideal of metaphysical aloneness as a key to understanding the project of Morning Cleaning. Fried argues that Wittgenstein’s thought-experiment, where he imagines ‘a man who thinks he is unobserved performing some quite simple everyday activity as if in a theatre’6 anticipates the ‘near documentary’ effect that Wall claims for his photographs: ‘In some way they claim to be a plausible account of, or a report on, what the events depicted are like, or were like, when they passed without being photographed.’7 Wittgenstein’s desire for works of art that would constitute ‘seeing life itself’8 is understood by Fried to be an antitheatrical ideal for which Wall’s cinematographic photography provides the salutary technology and technique. With its laborious and time consuming process of staging, of repeated film takes, and of painstaking digital manipulation, and, more, its final presentation as a back-lit transparency, Wall’s photographic method answers the desire for a specific interplay of realism and artifice that Fried detects in Wittgenstein. Via comparison with similarly absorptive moments in the painting of Chardin and others, Fried concludes that Morning Cleaning is a reinterpretation or renewal ‘across a jagged breach’9 of the antitheatrical aims of the high modernist painting and sculpture he investigated in his essays of 1966–67, notably ‘Art and objecthood’.

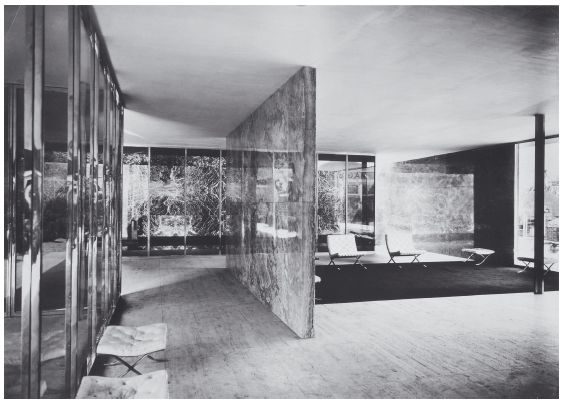

My difficulty with Fried’s argument lies not with his claim for the absorptive state of the window-cleaner, which is readily apparent, but with how he limits his gender neutral analysis to focus exclusively upon the figure of the worker at the expense of other compelling features of Wall’s photograph. Paramount here is the insistent bifurcation of the composition by Mies’s trademark cruciform column, which bars, or at least persistently interrupts, any lateral traversal of the pictorial space between the figures of Alejandro and Dawn, window-cleaner and sculpture. This pictorial tension in Morning Cleaning is brought into focus if we compare it to the Bild-Bericht images of the German Pavilion (plates 3 and 4), taken from much the same vantage point but distinguished by their relative proximity to the cruciform column. In the first instance, distance allows the viewer to vicariously circumnavigate the column and the ceiling, whereas proximity in the second photo splits the image decisively. Wall’s photograph takes up a position between these two, cropping the point of intersection between column and ceiling yet retaining a shallow foreground at floor level that invites a virtual entry into the broad pictorial space. The scale of Morning Cleaning, where the nickel-plated steel column is roughly the size of an adult figure, encourages an experience of the pictorial space as an illusionistic extension of embodied space. But the impulse to navigate that space visually is countered by the insistent presence of the column. Its spectral gleam doubles as a lure that retains the gaze of the spectator close to the picture plane and as a fractured reflection that suggests the extra-pictorial presence of the artist-photographer with his equipment.

This imaginary capture between animate and inanimate, male and female, is reminiscent of the dialectic of desire in Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass, and indeed, my argument in what follows is that the pictorial relations in Wall’s tableau may be understood quite differently from Fried’s account, if we consider Morning Cleaning as a Duchampian delay.10 The temporality of repetition and deferral in The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even, 1915–23 (plate 5) is quite different from the timeless optical presentness that Fried advances. The bifurcated field of Duchamp’s Glass interrupts the gaze of the modernist beholder, requiring a double look, or as Rosalind Krauss argues for Duchamp’s precision optics, ‘the blink of an eye’.11

5 Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915–23. Oil, varnish, lead wire, lead foil, mirror silvering, and dust on two glass panels (cracked), each mounted between two glass panels, with five glass strips, aluminum foil, and a wood and steel frame, 277.5 × 175.8 cm. As installed by the artist at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art (Bequest of Katherine S. Dreier). Photo: © Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP Paris/DACS, 2009.

ALLEGORICAL DESIRE AND THE POLITICS OF GLASS

The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even is shown in plate 5 as it was installed by the artist in the Philadelphia Museum of Art where Wall viewed it at the Duchamp retrospective mounted there in 1973–74.12 Wall had just returned from London after three years of research on Duchamp towards a PhD in art history at the Courtauld Institute.13 In an interview with Jean-Francois Chevrier, he recalls his encounter with Duchamp as a kind of epiphany:

Then images started coming back to me, almost like childhood memories, images from the period in which Duchamp’s work emerged: late Symbolism, Post-Impressionism, and so on. I had thought that Duchamp was important mainly for the way he participated in the destruction of that great pictorial culture. But the closer I looked, the more I saw him as a part of it. And through looking at his work I looked in a new way at everything around him, a way that reminded me of the enjoyment I’d experienced as a child in looking at books of reproductions of Seurat, Manet, or Brueghel. I thought I understood something of the real critical dimension of contemporary art: it wasn’t a matter of attacking or destroying, not a question of violence; rather it was about a militant exploration of the legitimacy of tradition. That’s how I began to define my own position, and how I still do now.14

Michael Newman has written persuasively on the decisive role of the French artist for Wall’s negotiation of an exit from conceptualism and the development of his now familiar tableau transparencies in the late 1970s.15 For Newman, the key work for Wall’s new role as director of cinematographic photography was not the readymades, so crucial to conceptual art, but the elaborate staging of Etant donnés which reintroduced the pleasure of seeing bodies, albeit as a self-conscious act of voyeurism, and served as a model for ‘constructing a picture or tableau that will prompt in the viewer a spectatorship that is both engaged – to the point of embarrassment indeed – and reflective, much like the attitude of the theatre audience proposed by Brecht’.16 The Large Glass plays a lesser role in Newman’s account, yet it is the allegorical desire of the latter that I propose played an important part in the conception of Morning Cleaning. While Duchamp’s play with the stereoscopic view of Etant donnés, by way of its peepholes, reveals the desire in vision, it also arguably feeds the eye as trompe l’oeil, offering a degree of erotic plenitude. By contrast, the resolute separation of feminine and masculine spheres in The Large Glass denies this satisfaction, frustrates the desire for a unified view; in short, ushers in the decentred, split subject of repression and longing.

In Morning Cleaning, the signifying function of Mies’s cruciform column, though it divides the picture vertically rather than horizontally, is analogous to the metal divide that bars any intercourse between Duchamp’s two panes of glass and helps retain the focus of the viewer on the surface of The Large Glass in spite of its transparency. The column in Wall’s photograph similarly interrupts our navigation of the pictorial space laterally, even though a closer look reveals the open access to the enclosed pool area on the right. As for the gendering of space in Morning Cleaning, correspondences with what Duchamp termed the ‘cinematic blossoming’17 of the Bride above her Bachelors are not difficult to discern: the nude figure of Dawn in the moment before her unveiling is analogous to the stripped Bride arrested by her own imaginative desire, while the intent pose of the cleaner with his angled squeegee pole and wheeled bucket echoes the raised bayonet of the chocolate grinder that grinds its own chocolate, supported on its Louis XV legs. Analogies may also be made between the distribution of light and fluids in Morning Cleaning and the playful physics of The Large Glass, with its multiple references to pre-war science and mathematics: the halo of the Bride as incandescent light bulb, the liquefaction of the Bride’s love gasoline, and the onanistic ‘splashing’ of the bachelors.18

However, The Large Glass is notoriously labyrinthine with its allegorical structure of image and text in the form of the Green Box and other published notes, and it is not my intention here to interpret Wall’s work through a simplistic iconographical mapping. Rather, considering Morning Cleaning as a Duchampian delay within the historical context of the pavilion it pictures, opens up a reading beyond thwarted sexual desire, and towards an allegory of the frustrated dreams of the modernist avant-garde to engage meaningfully with those of the proletariat, a failure at the heart of Wall’s critique of conceptual art. Wall’s awareness of the failure of conceptualism’s self-reflexive practice to effectively engage the social class that had inspired the earlier avant-garde presented an artistic conundrum. In his 1982 essay, ‘Dan Graham’s Kammer-spiel’,19 Graham’s work suggests a way out to him:

Graham begins from the failure of conceptualism’s critique of art. But his intention is not to celebrate that failure and to throw away the lessons of the radical art of the 1960s Rather, he intends with the Alteration project to build a critical memorial to that failure. And, in the spirit of the movement he memorializes, he builds it as a countermonument.20

In what follows, I will argue that Wall effectively returns to this strategy of the ‘countermonument’ in Morning Cleaning, and does so in ways resonant with the politics of modernist glass architecture set out in the Kammerspiel essay.

Reading Wall’s lengthy and densely argued essay on Graham’s Alteration to a Suburban House (1978) with an eye to Morning Cleaning is an experience not unlike reading Duchamp’s notes in relation to The Large Glass. Indeed, in his essay ‘The artiste’, Blake Stimson, while highly critical of Wall’s advocacy of Graham over other conceptual artists in the Kammerspiel essay, includes Morning Cleaning amongst the illustrations for his argument without comment, as if to suggest that their correspondence is self-evident.21 Wall’s central concern in his essay is to situate Graham’s project in relation to the symbolism of the glass architecture pioneered by Mies van der Rohe: the glass skyscraper and the glass house. For Wall, the revolutionary ideals of Weimar culture find only a faint echo in the Mies of the American Bauhaus, whose glass tower, with its asymmetric relations of surveillance and visibility, came to symbolize the sophisticated post-war corporate system that had ‘integrated all the massive systems of bureaucratic control and technological expedience identified with totalitarianism in the 1930s’.22 Stimson drives the point home: ‘more than any other single form, it might be said, the glass wall has operated as a motif for both the promise and the failure of enlightenment, and with it, both the promise and the failure of modernity.’23 As an icon of the ‘new American neocapitalist city’24 the glass tower found its domestic counterpart in the glass villas anticipated by Mies’s German pavilion and designed to house America’s elite. And it is the phantasmatic specular relations of these glass villas that are central to Wall’s analysis.

Alteration to a Suburban House was not actually realized but became known through photographs of architectural models and a published text that specifically referenced the glass houses built by Mies and Philip Johnson. Graham proposed replacing the façade of a suburban tract house with a wall of glass, while inserting a mirrored wall that bisected the house longitudinally and faced outwards, thus reflecting the street, the environment, and the façade of the identical house opposite as a kind of spectral presence. He associated the resulting effect with a ‘show window display’ or a ‘metaphoric billboard’,25 symbols of capitalist consumerism resonant with conceptualism’s critique of commodity fetishism and the spectacle, under the sway of Walter Benjamin and the Frankfurt school, though I am reminded too of the eroticism of the shop window relayed by Duchamp in the Glass.26 Indeed, there is a tension in Wall’s essay between the poetics of surrealist glass imagery and Benjamin’s more ‘materialistic, anthro-pological’27 concept of ‘profane illumination’.28 However, for Wall the critical mediating term for the Alteration project is the glass wall pioneered by Mies.

Wall’s claim for Graham’s Alteration as an intervention in ‘the illusory seam-lessness of social reality’29 rests upon his analysis of the effects of power encoded in the optics of the glass house or villa, idyllically set in a privately owned parkland. And it is here that his essay is most resonant with the bifurcated field of Morning Cleaning. By day the glass house is a belvedere securing a sovereign view of nature, a ‘regime of theoretical invisibility and blissful absorption’ for its privileged male occupant.30 But by night, the reversal of luminosity and visibility constructs a mirrored locus of phantasmatic anxiety represented by the fantasy of the vampire, an apparition trapped in the mise-en-abyme of reflections, that casts the glass house as a mausoleum or crypt. The apparition of the vampire emerges for Wall as a sign of residual evil inherited from the unresolved crises of the old order, a sign of uneasiness with the social order of the modern, and it figures in a number of his subsequent back-lit transparencies.31

Wall observes that the mirror that bisects the house longitudinally in Graham’s Alteration project is more highly reflective than its glass facçade, and in daytime this superior reflectivity has the effect of returning the glass wall to transparency. The dichotomous relation of interior to exterior is thus cancelled, and the relations of asymmetrical social status secured by the glass house as belvedere/crypt are annulled.32 In Alteration, the tyranny of the mirror reflects occupants and passers-by equally on either side of the transparent glass wall, revealing their homelessness in the oppressive greyness of suburbia, imagined earlier in his essay as ‘the garden of subjection for a lost proletariat’.33 For Wall, this transparency does not introduce a moment of liberation but a prolonged moment of traumatic truth, ‘an image of historical apocalypse’ and ‘of the failed liberation of the world’.34 What is revealed for him in Graham’s bleak exposure of ‘the vampiric nihilism hidden within high bourgeois art-culture’ is the defeatism of the conceptualist strategy of intervention which, detached from the working class as a social force, can only intervene in the name of art itself.35 Hence, he understands Graham’s project as ‘an antimonumental memorial to conceptualism’s limitations’.36

This strategy of the countermonument as a moment of traumatic transparency is worth considering in relation to Morning Cleaning, for certainly the Barcelona Pavilion invokes a fraught relation to history and memory. In his essay, ‘Body in pieces: desiring the Barcelona Pavilion’, George Dodds declares the 1929 German Pavilion to be ‘a virtual ur-hut of modernity, [yet] the one building by Mies about which the least can be said with certainty’.37 Though a temporary building, dismantled in 1930 after only seven months, the German Pavilion has been enormously influential as the privileged architectural signifier of the utopian values of the avant-garde – the Mies of the Bauhaus and the November Gruppe, of such polemical magazines as G and Frühlicht – at the moment before the catastrophe of Fascism. At the same time, it is the vanguard of the International Style and of the eventual inversion of Weimar values by the modernism of the American Mies, subsumed into the Cold War corporate agenda, about which Wall writes: ‘Mies’s architecture, in invoking through its purity the consciousness of its own vanquishment, maintains thereby a faint echo of the unfulfilled hopes of the period of optimism. It therefore remains significant as a negative symbol and, if it is looked at historically, takes on, however weakly, some characteristics of the antimonument.’38 Given the status of the 1929 pavilion as a site of lost hopes and desires, what might it mean for Wall to photograph the reconstructed pavilion that opened to the public in Barcelona in 1986?

PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE DREAM OF MODERNITY

George Dodds tells us: ‘The story of the Barcelona Pavilion is intrinsically related to the medium through which it has been primarily apprehended, before its demolition and after – photography’.39 Dodds is primarily concerned with the thirteen master prints from 1929 housed in the Mies van der Rohe Archive at the Museum of Modern Art known as the Berliner Bild-Bericht photos.40 While the catalogue of the International Exposition has some photos that include people, the Bild-Bericht photos, reproduced in virtually every monograph, article and textbook on Mies’s work, depict a pavilion in the form of a house where no one ever seems to be home.41 Rather, their myriad reflections (plate 6) and carefully arranged custom designed furniture cleansed of any trace of experience (the famous Barcelona chairs designed with Lily Reich), suggest an inversion of Walter Benjamin’s ‘phantasmagoria of the interior’,42 whereby décor is returned to the status of the fetishized commodity. Wall explicitly makes this connection to the ünheimlich (unhomelike), uncanny dwelling in his Kammerspiel essay.43 It is these photos, preserving the ‘timeless perfection of the pavilion’s mirror-like walls’,44 that Mies valued and took to America, while forgoing the opportunity to preserve the actual pavilion.45 And, according to Dodds, Mies’s soaring reputation by the late 1940s was, alarmingly for some contemporaries, almost entirely based upon photographs of projects that his peers had never seen.46 The master prints are the only photographic images of the pavilion that he approved for printing after moving to Chicago. This authoritative status accounts for the fact that they formed the primary basis for the reconstruction in the 1980s along with some original sketches and plans of dubious accuracy. Dodds argues that photography has played a central role in the ‘sedimentation of mythology’ around the pavilion, generating ‘what appears to be a kind of delirium in those who attempt to interpret the image of this building ... the Bild-Bericht prints must be understood not only as the figure of a building but also as the reflection of a desire – a collective desire to inhabit the unstable image of what has become, during this century, a reoccurring dream of modernity.’47

6 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (architect), Williams & Meyer Co. (photographic studio), Interior view of the German Pavilion at the Barcelona International Exposition, 1929–30, Barcelona, Spain. Gelatine silver print, 16.3 × 22.9 cm. Montréal: Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture (Gift of Edward Austin Duckett). Photo: © CCA, Montréal/Lohan Associates/DACS, 2009.

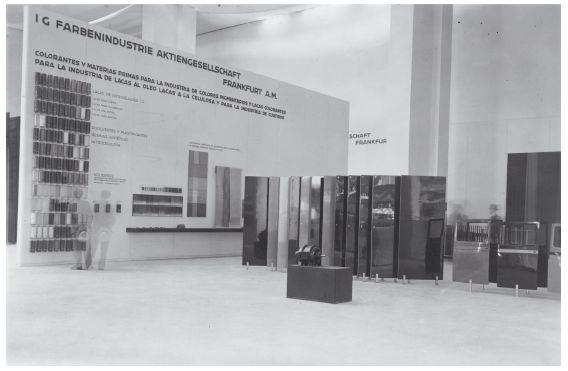

Like Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, also known mostly through photographs, the German Pavilion inspires fantasy. At the opening in Barcelona in 1986, Mies’s daughter Georgia praised it as one of the most beautiful buildings of our century, stating ‘now, we can even touch the onyx wall’,48 referring to the marvellous piece of onyx doré illuminated in Morning Cleaning. This revealing slippage that fails to distinguish between original and reconstruction, that is to say, between two disparate historical moments disavows crucial differences in the respective pavilions’ functions. The 1929 pavilion was intended as a reception space for the inauguration by King Alfonso XIII and worked in conjunction with the displays of German industrial products in the exhibition hall designed by Mies and Lily Reich (plate 7), to present, as Josep Quetglas tells us, the modern German soul as a function of work: ‘modernised, transparent, crystalline, electric’.49 This was a moment of confluence between the language of avant-garde utopianism and the rhetoric of the Social Democrats, however much Walter Benjamin later decried their vision of technologized labour as progress.50 However, the reconstructed pavilion speaks to another historical moment of late capitalism, where the pavilion itself is the display, so that the vision of the worker in Morning Cleaning is not the heroic, masculine figure of industrial production, but the somewhat feminized maintenance worker associated with minimum wages and tourism.51 The reconstructed pavilion is a museum, a tourist attraction, a ruin, emptied of utopian social meaning, a testament to the death of the avant-garde, offering instead aesthetic pleasure in the petrified beauty of Mies’s rich, reflective materials. As such it calls to mind what Wall declares to be the question posed by conceptualism: ‘What is the process in which the cultural crisis is not resolved socially, but transmuted into sublime fixation upon immobilized symbols and fetishes?’52

7 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, View of the I. G. Farben exhibit, Barcelona International Exposition 1929–30, German Section, Spain. Gelatine silver print, 10 × 14.8 cm. New York: Museum of Modern Art (Anonymous gift, AD163). Photo: © The Museum of Modern Art/SCALA/ARS, NY (2009)/DACS, 2009.

A similar anxiety seems to have provoked the subversive exhibit organized by the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas and his Office of Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) for the Milan Triennale in 1985 – a response to the reconstruction in Barcelona. As Derek Sayer recounts, Koolhaas raised the question of how fundamentally did this ‘clone of Mies’s pavilion ... differ from Disney’. Koolhaas continues:

In the name of a higher authenticity we researched the true history of the pavilion after the closing of the 1929 World’s Fair and collected whatever archaeological remnants it has left across Europe on its return journey. Like a Pompeian villa, these fragments were reassembled as far as possible to suggest the former whole, but with one inevitable inaccuracy: since our ‘site’ was curved, the pavilion had to be ‘bent’.53

Koolhaas and OMA created an absurdly fictitious account of the fate of the original pavilion, performing a vicarious witnessing of the events following its actual dismantling in 1930: the Spanish Civil War, Nazi spectacles, the massive bombing of Germany, Cold War politics in East Germany, and finally the discovery of the pavilion’s remnants by a Western scientist.

In his essay ‘Three thoughts on photography’ written in 1999, the same year as Morning Cleaning, Wall declares: ‘Now I see the possibility of developing a mimesis of photography, as photography.’54 What he means by this is that photography as a printed medium has joined the older media of painting and drawing as ‘unilluminated’, that is, not illuminated in the manner of his back-lit transparencies, and hence, not reliant upon electricity in order to be seen. So while in the past Wall has used paintings as models for his back-lit photos, now he can include print photography in what he calls ‘the mimetic game’. I propose that Morning Cleaning, then, is a mimesis of the Bild-Bericht prints of 1929.

In an interview with Craig Burnett, Wall reveals that his photograph was taken only five inches away from one of the cardinal points in the standard photographic views of the pavilion.55 That ‘standard view’, by my measurements, is the Bild-Bericht photo illustrated in plate 4 in which Dawn is illuminated by the morning sun.56 While Wall has stepped back to allow for greater distance from the column, the horizontal scope that encompasses the window on the right with the red curtain is a function of his cinematographic method of shooting the scene. Morning Cleaning is more emphatically horizontal in its proportions than any of the Bild-Bericht photographs.57 The other crucial difference is in the effects of light. In both of the standard views of the ‘throne room’ (plates 3 and 4) the lighting feeds the illusion of the veined marble wall as an organic presence, continuous with the landscape of cypresses and conifers beyond. It also renders the tinted glass wall nearly opaque in a manner that suggests the reversal of luminosity of the glass house at night, as described in the Kammerspiel essay. Note that this lighting effect is not consistent across the master prints, as can be seen in the virtual transparency of the window in plate 6.58 In Morning Cleaning Wall chooses the same time of day as his model but his lighting reverses the relationship of visibility. The marble is in sharper focus so that the architectural enclosure is distinct from the foliage beyond and, hearkening back to Graham’s Alteration project, the glass wall is transparent so that inside and outside are continuous. Except, that is, for the provisional interference of the soapy film that anticipates the moment of awakening, heralded by the beam of light on the onyx wall. The anamorphic Dawn, caught in an ambiguous movement (greeting the sun? protecting herself from its glare?) threatens to disrupt the tranquillity of the house, heralded in 1929 as a symbol of the new German spirit: transparent, forthright, honest and pacified.59 Meanwhile, the window cleaner remains caught in the midst of the repetitive task of removing all traces of lived experience, restoring decorum.

As a mimesis of a photograph, Morning Cleaning functions allegorically as a palimpsest to overwrite the erection of the Barcelona pavilion as fetish, as a symbol of a history emptied of social meaning, as a monument to architectural modernism that covers over the traumatic history of modernity in the intervening years between the indexical moment of the Bild-Bericht photo and its own. It functions then as a countermonument, calling into question the premises of its own construction, a concept that took on particular significance during the 1980s as the generation of Germans born after 1945 wrestled with Germany’s ‘memorial conundrum’ and the need to comprehend the historical gap between the Holocaust and their own lived experience.60 The same year that the Barcelona Pavilion was opened, Jochen Gerz and Esther Shalev-Gerz unveiled their Monument against Fascism in Harburg, a Gegen-Denkmal (countermonument) designed to slowly sink into the ground and disappear. However, whereas projects like the Gerzes’ were participatory sites for the work of memory and mourning, Morning Cleaning remains a picture in an exhibition.

It seems that Duchamp had a secret intention when designing the installation of his work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1954. According to his biographer, Calvin Tomkins, the door-like window visible in plate 5 facing onto the courtyard with its large fountain ‘had been cut into the wall on his instruc-tions’.61 On the other side of the fountain, directly in line with the Glider in The Large Glass, stood a nude female figure in bronze depicting a Brazilian water nymph called Yara (plate 8). This sculpture, which remains in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, was created by the Brazilian artist Maria Martins, a married woman with whom Duchamp had a passionate, clandestine affair during the 1940s in New York.62 She eventually ended the relationship despite his entreaties to leave her husband, the Brazilian ambassador to Washington, and her family. Martins was the ‘Maria’ in the original title of Etant donnés63 and it is supposed that she was the model for the female nude in that work so shockingly displayed when installed, after Duchamp’s death in 1968, just a few steps away from the Glass. Indeed, for many years she was the only one who knew that Duchamp was working on what would eventually become Etant Donnés, referred to in their correspondence as ‘N.D. [Notre Dame] des désires’.64 The significance of this sight-line that connects the two ‘Brides’ who were beyond Duchamp’s grasp was not revealed until the early 1990s.65

It is open to conjecture whether Wall is making an ironic reference to this fact in Morning Cleaning, but he does nonetheless enjoy secrets of his own. That is to say that Wall may have his own cause for the kind of personal satisfaction that Duchamp enjoyed in viewing The Large Glass installed. However, in Morning Cleaning this privileged knowledge concerns a dark and enigmatic presence that points not to unfulfilled passion, but to the historical trauma covered over by the pavilion as fetish.

In 1999, Wall was invited by Hilda Teerlinck, curator at the Mies van der Rohe Foundation, to exhibit in the pavilion in Barcelona as part of a larger project of artists’ dialogues with the architecture. This gained him the cooperation of the Mies van der Rohe Foundation to photograph Morning Cleaning, and by Wall’s account, allowed him to further investigate, by way of the window washer tableau, a theme explored in other works: cleaning.66 In Just Washed, 1997, for instance, a soiled white cloth, not unlike the one on the floor in Morning Cleaning, is held above an open washing machine in a manner mimicking an ad for laundry detergent. The ambiguity of the title suggests that cleaning is a repetitious, cyclical activity that does not eliminate dirt but merely displaces it from one surface area to another – removes it from view. This persistence of dirt and its attendant anxiety in Western culture takes on symbolic weight when we consider the works installed in the pavilion for Teer-linck’s project: an earlier back-lit transparency entitled Odradek, Tabor-itska 8, Prague, 18 July 1994 (1994) (plate 9) and a small sculpture called Odradek which can be seen in plate 10 positioned next to the marble wall and just beyond the red curtain. The entry in the Jeff Wall Catalogue Raisonné explains that two of these wooden spool-like pieces were made in case one was damaged, hence, Double Odradek (plate 11).67 The artist housed them in a wooden case reminiscent of the croquet box used by Duchamp in 1936 to assemble his 3 Standard Stoppages, 1913–14, even including a package of beeswax for conservation purposes. While both the transparency and the sculpture were present during Wall’s filming, neither of these works is visible in Morning Cleaning.68 Yet, considering them here further substantiates my claims for Morning Cleaning as countermonument.

8 Maria Martins, Yara, c. 1940. Bronze sculpture, 207.6 × 71.1 × 73.7 cm. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art (Purchased with funds from an anonymous donor, 1942). Photo: Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Odradek is an enigmatic creature that figures in a short story by Franz Kafka, written in 1919, entitled ‘Die Sorge des Hausvaters’ translated as ‘The Cares of a Family Man’.69 The story has been reproduced as a text panel to accompany the back-lit photograph Odradek, Taboritska 8, Prague, 18 July 1994 and was selected by Wall to be included in his Phaidon monograph, under the rubric of ‘artist’s choice’. Here is an excerpt:

At first glance it looks like a flat star-shaped spool for thread, and indeed it does seem to have thread wound upon it; to be sure, they are only old, broken-off bits of thread, knotted and tangled together, of the most varied sorts and colours. But it is not only a spool, for a small wooden crossbar sticks out of the middle of the star, and another small rod is joined to that at a right angle. By means of this latter rod on one side and one of the points of the star on the other, the whole thing can stand upright as if on two legs.70

In Kafka’s story, Odradek vacillates between inanimate object and live creature and ‘lurks by turns in the garret, the stairway, the lobbies, the entrance hall’.71 This is what we see in Odradek, Taboritska 8, Prague, 18 July 1994, albeit with some difficulty, as the young woman descending the staircase is oblivious to the barely detectable presence of Odradek on the stained floor adjacent to the stairs. Odradek is nimble and eludes close scrutiny, though he can be heard laughing – a sound like ‘the rustling of fallen leaves’.72 The allusion to Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, 1912, and by association the chronophotography of Etienne-Jules Marey, has been taken up by Jean-Christophe Ammann and Michael Newman, though in an interview with Craig Burnett, Wall has flatly denied any such reference.73 Newman extends his reading to include the sink in the foreground as Duchamp’s readymade urinal Fountain, 1917.74 His argument that Wall is critiquing the readymade here connects the figure of Odradek with the genealogy of failed modernism elucidated in Wall’s Kammerspiel essay. The anxiety to which the readymade gives expression in Wall’s account is compared to the painful speculation of the ‘Family Man’ or father/narrator in Kafka’s story that Odradek, a useless object that will never wear out or die, will likely outlive him, his children, and his children’s children, persisting across the generations.75 If indeed one can argue for Odradek, Taboritska 8, Prague, 18 July 1994 (a title that suggests a snapshot) as some kind of commentary on the readymade, I am inclined to view the shadow of the spigot in light of Duchamp’s Tu m’, 1918, as an indexical sign that points to the soiled and stained surfaces of this bleak interior, so sharply illuminated by the photographer’s equipment, as historical traces.

9 Jeff Wall, Odradek, Taboritska 8, Prague, 18 July 1994,1994. Transparency in light-box, 229 × 289 cm. Photo: © Jeff Wall.

10 Jeff Wall, Odradek, installation view, Mies van der Rohe Foundation, Barcelona, Spain, 1999. Photo: Biel Capplonch, Barcelona. © Jeff Wall.

11 Jeff Wall, Double Odradek, 1999. Each sculpture 18.5 × 16 × 26.3 cm; case 9.5 × 60.5 × 22.5 cm. Collection of the artist. Photo: Museum fur Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt Am Main/Axel Schneider. © Jeff Wall.

The rich commentary on Odradek circulates around the tropes of memory, mourning, and the dread of the uncanny. In his Kafka essay, Walter Benjamin aligns Odradek with the vectors of guilt and forgetfulness. He writes: ‘in Kafka’s work, the most singular bastard which the prehistoric world has begotten with guilt in Kafka is Odradek. . . . Odradek is the form that things assume in oblivion. They are distorted.’76 Rebecca Comay identifies Odradek as the name of the bobbin Freud’s grandson played with so famously in the game of Fort-Da, a game of disappearance and return beneath the curtain surrounding his crib, allegori-cally signifying the work of mourning, ‘the impossibility of all restitution and as such the radical Unheimlichkeit of every home’.77 Slavoj Zizek, in his essay ‘Odradek as a political category’ describes Odradek as ‘a partial object’, the ‘inhumanhuman “undead” organ without a body’, a kind of remainder of the Life-Substance that escapes symbolic colonization.78 His recognition of Odradek in relation to Lacan’s myth of the lamella, a figure of pure libido that escapes the mortality of sexuated generative beings, leads him to link Kafka’s creature to the alien in the Ridley Scott film of that name, and thus to a latent horror commensurate with ‘the Real as the monstrous thing behind the veil of appear-ances’.79 Zizek’s essay aligns Odradek etymologically with the Greek dodekae-dron, a volume of twelve faces, each of them a pentagon. But as you can see, Wall’s Odredek is not a pentagon at all. It is clearly a six-pointed star.

Wall recounts his trip to Prague in 1994 as a kind of game to hunt for Odradek: ‘If Odradek had survived the Holocaust (and I think he is one of those most likely to have done so) he’d be hanging around where he always hangs around. He wouldn’t have gone anywhere.’80 Though the address Taboritska 8 is not related to Kafka particularly, it evokes, through the liminal presence of Odradek, the lost culture of Central European Jewry that survives in Kafka’s writing. This dilapidated house in Prague that has borne witness to the failures of utopian modernism in the twentieth century is, in its murky accretions and sad decrepitude, the antithesis of the pristine pavilion filmed by Wall at the end of the millennium. The resonance of its installation in Mies’s space as a photographic image along with the sculpture Odradek, scarcely needs further elaboration, even without knowledge of Wall’s own Jewish heritage.81 But what of its haunting presence in Morning Cleaning?

In Morning Cleaning, what is rendered invisible by Wall’s cinematographic technique is the temporal unfolding of the extended filming process. Unlike the disjuncture of avant-garde photomontage that exposed social contradictions – in Benjamin’s view, a modern form of allegorical critique – Wall’s cinematographic photography presents a seamless view more reminiscent of the montage in architectural drawings. It establishes a spatial continuity and intimacy that allows him, he claims, to negotiate ‘phantom identifications’ without drawing sharp distinctions ‘between the prosaic and the spectral, between the factual and the fantastic, and by extension between the documentary and the imaginary’.82 Odradek is just such a phantom of transgenerational memory.

Wall has suggested somewhat playfully that the Kammerspiel essay was a sort of Duchampian delay with respect to his longtime interest in art criticism.83 My argument leads to the conclusion that Morning Cleaning is also a Duchampian delay that, perhaps more than any other work by Wall, transforms the locus of concerns that informed that essay into a picture. But a picture where the insistent bifurcation of the visual field reminds us of the illusionary reality obtained through the persistence of vision, the very basis of the cinematic apparatus, and provokes a double look that leaves us caught by desire.

Notes

I would like to thank Tamara Trodd for her delightful enthusiasm in response to this chapter at the AAH conference in 2008 and especially for alerting me to the presence of Maria Martins’ sculpture at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I have benefited from conversations with Michael Taylor at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and from the commentary of faculty at Carleton University, where I presented a version of this chapter at the Art History Colloquium in Visual Culture. I am deeply grateful to Margaret Iversen and Diarmuid Costello for including me in their project and for their perceptive comments and direction in shaping this chapter. And I further appreciate the careful consideration and insights of my reader which have helped me immensely in clarifying my argument.

1 The figure of Dawn in the pool of the reconstructed pavilion is a cast replica of the original bronze sculpture that was used in 1929. See George Dodds, Building Desire, London and New York, 2005, 18.

2 Description of the project by Jeff Wall in Michael Fried, ‘Jeff Wall, Wittgenstein, and the Everyday’, Critical Inquiry, 33: 3, 2007, 515.

3 Penelope Curtis, ‘The modern eye-catcher: Mies van der Rohe and sculpture’, Arq, 7: 3/4, 2003, 361.

4 Curtis, ‘The modern eye-catcher’, 369.

5 Theodora Vischer and Heidi Naef, eds, Jeff Wall: Catalogue Raisonne’ 1978–2004, Basel and Göttingen, 2005, 393.

6 Fried, ‘JeffWall’, 519.

7 Wall’s statement, 2002, cited in Fried, ‘JeffWall’, 506.

8 Fried, ‘JeffWall’, 518.

9 Fried, ‘JeffWall’, 525.

10 This reading of Morning Cleaning in relation to The Large Glass was initially formulated in response to Michael Fried’s lecture ‘Jeff Wall, Wittgenstein, and the everyday’ at the National Gallery of Canada, 10 September 2006.

11 Rosalind Krauss, ‘The blink of an eye’, in David Carroll, ed., The States of ‘Theory, New York, 1990, 175–99.

12 Michael Newman, ‘Towards the reinvigoration of the “Western tableau”: some notes on Jeff Wall and Duchamp’, Oxford Art Journal, 30: 1, 2007, 86.

13 Michael Newman, ‘Towards the reinvigoration of the “Western tableau”‘, 81.

14 ‘Interview between Jeff Wall and Jean-Francois Chevrier: writing on art (2001)’, in Jeff Wall: Selected Essays and Interviews, New York, 2007, 320.

15 Michael Newman, ‘Towards the reinvigoration of the “Western tableau”‘, 85.

16 Newman, ‘Towards the reinvigoration of the “Western tableau”‘, 86.

17 ‘The cinematic blossoming is the most important part of the painting . . . It is, in general, the halo of the bride.’ Marcel Duchamp, Notes and Projects for The Large Glass, Intro. Arturo Schwarz, New York, 1969, 26.

18 Though it may only be coincidental, Duchamp’s etching The Large Glass Completed, 1965, identifies the upper left area of the Bachelors’ glass pane as the ‘region of the waterfall’ (Linda Dalrymple Henderson, Duchamp in Context: Science and Technology in the Large Glass and Related Works, Princeton, NJ, 1998, fig. 77) while his notes reveal that soapy water or tinted glass were, in fact, the materials he considered in order to ‘provide a provisional opacity made by the splashes from upstream and down’. Duchamp, Notes and Projects, 54,122.

19 Jeff Wall, ‘Dan Graham’s Kammerspiel’, in Jeff Wall: Selected Essays and Interviews, New York, 2007, 31–75.

20 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 31.

21 Blake Stimson, ‘The artiste’, Oxford Art Journal, 30: 1, 2007, 101–15.

22 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 50.

23 Stimson, ‘The artiste’, 105.

24 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 50.

25 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 48.

26 Henderson, Duchamp in Context, 173–4.

27 Detlef Mertins, ‘The enticing and threatening face of prehistory: Walter Benjamin and the utopia of glass’, Assemblage, 29, April 1996, 10.

28 Walter Benjamin, ‘Surrealism: the last snapshot of the European intelligentsia’, in Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland and Gary Smith, eds, Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Volume 2: 1927–1934, Cambridge, MA and London, 1999, 209.

29 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 65.

30 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 60.

31 Tom Holert considers the figure of the vampire as a ‘symbolic prosthesis’ for the artist’s own subjectivity as it is inscribed in the specular relations of his cinematographic photos, including Morning Cleaning. See Tom Holert, ‘Interview with a vampire: subjectivity and visuality in the works of Jeff Wall’, Jeff Wall: Photographs: MUMOK, Wien and Köln, 2003,128-37.

32 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 67.

33 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 43.

34 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 69.

35 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 75.

36 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 73.

37 George Dodds, ‘Body in pieces: desiring the Barcelona Pavilion’, Res, 39, 2001, 173.

38 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 56.

39 Dodds, ‘Body in pieces’, 169.

40 The most comprehensive study of these master prints is Dodds, Building Desire.

41 Dodds, ‘Body in pieces’, 174.

42 Walter Benjamin, ‘Paris, the capital of the nineteenth century’, in Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, eds, Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings Volume 3:1935–1938, Cambridge, MA and London, 2002, 38.

43 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 54.

44 Dodds, ‘Body in pieces’, 174.

45 One explanation that George Dodds offers for Mies’s indifference to the fate of the building once the Bild-Bericht photos had been taken is that ‘the power of these photographic images would be substantially intensified by the erasure of the building’, in Building Desire, 120.

46 Dodds, ‘Body in pieces’, 183.

47 Dodds, ‘Body in pieces’, 174.

48 Remei Capdevila Werning, ‘Construing reconstruction: The Barcelona Pavilion and Nelson Goodman’s aesthetic philosophy’, MS Thesis, MIT, 2007, 42.

49 Josep Quetglas, Fear of Glass: Mies van der Rohe’s Pavilion in Barcelona, Basel, Boston, Berlin, 2001, 27.

50 Walter Benjamin, ‘On the concept of history’, in Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, eds, Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings Volume 4: 1938–1940, Cambridge, MA and London, 2003, 393.

51 Wall describes the three people responsible for cleaning the Barcelona Pavilion: Victor the supervisor, Alejandro who is in the photograph, and Esperanza. He adds ‘Esperanza’s view is that men don’t know how to clean’, in Vischer and Naef, Jeff Wall: Catalogue Raisonne’, 393.

52 Wall, ‘Kammerspiel’, 33.

53 Derek Sayer, ‘The unbearable lightness of building: a cautionary tale’, Grey Room, 16, 2004, 8.

54 Jeff Wall, ‘Three thoughts on photography (1999)’, in Vischer and Naef, Jeff Wall: Catalogue Raisonné, 441. While the essay was not published until 2005, Wall discussed the possibilities of ‘a photographic mimesis of photography’ in 1998. See ‘Boris Groys in conversation with Jeff Wall’, in Jeff Wall: Selected Essays and Interviews, 299.

55 Craig Burnett, Jeff Wall, London, 2005, 90–1.

56 Dodds, Building Desire, 70, fig 2.4.

57 For an inventory and dimensions of the photos in the MoMA collection see Dodds, Building Desire, 47 n 3.

58 Dodds, Building Desire, 71, fig 2.5.

59 The status of the pavilion as a ‘home’ was remarked in a French review of the 1929 pavilion, which interpreted its tranquil domesticity in terms of German appeasement: ‘Voilà la maison tranquille de l’Allemagne apaisée!’ Tuduri, Nicolas M. Rubio, ‘Le Pavillon de l’Allemagne a l’Exposition de Barcelone’, Cahiers d’Art, 4, 1929, 9.

60 James E. Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning, New Haven and London, 1993, 27. See especially Chapter 1, ‘The counter-monument: memory against itself in Germany’.

61 Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp: A Biography, New York, 1996, 389.

62 I am indebted to Tamara Trodd for drawing my attention to the existence of Maria Martins’ sculpture Yara in the courtyard, in response to my paper at the session ‘Photography after Conceptual Art’ at the Association of Art Historians Conference, London, 2008. Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holder of this work of art.

63 The first study for the secret work is a signed pencil drawing dated 1947 with the handwritten title Etant donne’s: Maria, la chute d’eau et le gaz d’éclairage. Tomkins, Duchamp, 357.

64 ‘Our Lady of Desires’, Tomkins, Duchamp, 366.

65 Henderson, Duchamp in Context, 217. Francis M. Naumann includes an illustration of Yara in Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Ghent and Amsterdam, 1999.

66 Burnett, Jeff Wall, 76.

67 Vischer and Naef, Jeff Wall: Catalogue Raisonné, 392.

68 While Wall does not recall the exact location of the light-box transparency in the Barcelona pavilion, he did confirm that the wooden sculpture was present during the photographing of Morning Cleaning. Email correspondence 2 November 2008.

69 Franz Kafka, Franz Kafka: The Complete Stories, ed. Nahum N. Glatzer, New York, 1972.

70 Thierry De Duve, Arielle Pelenc, Boris Groys and Jean-François Chevrier, Jeff Wall, London, 2002, 72.

71 De Duve et al., Jeff Wall, 72.

72 De Duve et al., Jeff Wall, 72.

73 See Jean-Christophe Ammann, ‘Odradek, Tébor-itské 8, Prague, 18 July 1994’, Jeff Wall: Figures and Places, Selected Works from 1978–2000, ed. Rolf Lauter, Munich and New York, 2001, 136–7; Michael Newman, ‘Jeff Wall’s pictures: knowledge and enchantment’, Flash Art, 28: 181, MarchApril 1995, 78; Newman, ‘The true appearance of Jeff Wall’s pictures’, Jeff Wall, Tilburg, 1994, 29–31. Craig Burnett’s interview with the artist is in Burnett, Jeff Wall, 77.

74 Newman, ‘Towards the reinvigoration of the “Western tableau”‘, 94.

75 He quotes Wall as follows: ‘The celebrated anxiety to which the Readymade gives expression is one generated by the glimpse it gives of a future implied by the eternity of the commodity, the endless rule of the abject object.’ Newman, ‘Towards the reinvigoration of the “Western Tableau”‘, 94 n 37.

76 Walter Benjamin, ‘Franz Kafka’, in Jennings et al., Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Volume 2, 810–11.

77 Rebecca Comay, ‘Mourning work and play’, Research in Phenomenology, 23: 1,1993,111.

78 Slavoj Zizek, The Parallax View, Cambridge, MA and London, 2006, 119–20.

79 Slavoj Zizek, ‘Troubles with the real: Lacan as a viewer of alien’, in How to Read Lacan,.http://www.lacan.com/zizalien.htm. Zizek uses the term sexuation, coined by Jacques Lacan in his Seminar XX (1972), to specify the production of a sexed subject position that is not determined by anatomy or gender.

80 Burnett, Jeff Wall, 76.

81 Arthur Lubow, ‘Jeff Wall: the luminist’, The New York Times Magazine, 25 February 2007, 58 (L).

82 ‘At home and elsewhere: a dialogue in Brussels between Jeff Wall and Jean-François Chevrier (1998)’, in Jeff Wall: Selected Essays and Interviews, New York, 2007, 292.

83 ‘Interview between Jeff Wall and Jean-Francois Chevrier: writing on art (2001)’, 317.