24

I took my last voyage in the spring of 1991, the MV Spanish Key out of Felixstowe to Gydnia via Copenhagen. A mixed cargo, a Polish crew, the clouds impossible to read. Nothing but lowering stratocumulus.

I remember — the crew were sympathetic. They kept out of my way, they gave me the run of the bridge. I ate alone in the day cabin, and didn’t raise my voice.

Through the gas fields of the North Sea and the cloud broke. Past the nervous coast of Denmark, Helsingør Castle floodlit in the night, crates of beer stacked on the quay at Copenhagen, the sound of the crew cheering a woman as she waved from the deck of a sail training ship…

The Baltic… it was calm and blue, and with the Spanish Key on automatic pilot I sat back in the helmsman’s chair. The ocean spread before me, the sun above, seabirds drifting. The crackle of the radio, the sweep of the radar, the blink of a dozen lights. The horizon dulled into the sky while Poland grew to the south.

I was experienced, trusted with twelve thousand tons of cargo ship and a crew of eighteen men. I had money in the bank and luck drifted in my wake. Some women had remembered me; dogs liked me. I had no unsavoury personal habits, and I did not hold grudges. I did not believe in God but I read at least one book a week. I had never been unemployed but I had never worked on land. The sea owned me, and as it washed by I wished it would tell me what I was going to do. Where could I go? Would I die without it; would my luck dry up? Had I made a mistake; should I have bought a yacht and sailed the islands of Polynesia? Should I buy a dog?

I got down from the helmsman’s chair and stood over the chart table. I picked up the dividers and checked the position. Perfect. I looked outside and checked the clouds. Exactly fourteen nautical miles off Rozewie, entering the Gulf of Danzig.

I spent my last run ashore in Gdansk. I drank coffee and ate a pastry in a main street café, an expensive place with huge tables and carved chairs. The smell of a sweet perfume hung in the air.

I went to the cinema and saw a Polish film about an apple picker, a piano player and the rites of spring. I didn’t understand a word but I enjoyed it, I enjoyed the dark. I felt slow and as I watched the credits I wanted to stay where I was, I did not want to go home.

‘I retired on the first day of May.

‘I took a train from Felixstowe to London, and visited my mother’s grave. It was raining. Her stone and the earth told me nothing. I laid some flowers on the grass, but as I was doing it I felt bad and empty. I wanted to talk to her, to tell her that her cap had protected me, and I wanted to ask her what I should do. I wanted to get down on my knees but I couldn’t bend, the words broke, the thoughts faded away. I walked away with no idea.

‘I had a niece in Liverpool. I phoned her and she invited me to stay, but when we met I didn’t recognise her and we had nothing to say. She watched television during the day and stayed out all night, every night. She didn’t have a book in the house, or any pictures on the walls. So I packed my sea-bag, left a note on her kitchen table and began to voyage through the country.

‘As I travelled, I followed the direction of clouds. When I left Liverpool they were drifting north-east, so I walked towards the Yorkshire Dales, and I got work building a wall. Later the clouds blew to the west, and I blew to the Lakes. I loved the Lakes. You’d love the Lakes…

‘I worked for a boatman at Coniston. It was my job to take money from tourists who wanted to rent rowing boats on the lake. I enjoyed that. I stayed for the summer. I let the clouds drift without me.’

‘Then…’

‘One foot in front of the other.

‘The autumn came and I followed a flight of cirrus south. I think I ended up in Wales. I remember painting a farmer’s caravan and playing with his dogs on the beach. Or maybe he only had one dog… I remember the place, though, in Dyfed. It was along the coast from Fishguard.

‘I became a story sailors tell, the one about the old captain who travels the earth looking for the comfort the ocean used to give him, reading the shape of clouds as he once read the swell of waves. He stands at crossroads and can hear waves as they break a hundred miles away, and he always heads towards them. He carries a shell in his pocket and wears a cauled cap on his head.’ I put my hand in my pocket and pulled out a shell. I put it on the bed. ‘That’s it.

‘One day a cloud drifted here and stopped, and it chose this place for me. West as feet can follow, the sea a pool of tears… It told me to rest and I thought, I’ve done enough walking. That’s enough. The cloud moved on but I stayed. I bought the house, I started the garden, I frightened the natives and then…’

‘What?’

‘You came.’ I took her hand and she rested her head on my shoulder. ‘You came.’

She said, ‘I almost didn’t.’

I had put glass in the windows. A single cloud crossed the face of the moon. Its shadow caught the side of the house and spilled into the bedroom. We watched it cross the floor and spread up the far wall before fading.

‘But you did.’

‘I did,’ she said, as another cloud shadowed the room.

I lay back and listened to the sea rustling along the shore, and the call of a distant bird. I shifted my legs and she shifted towards me, and when I closed my eyes I heard the darkness sing, and the clouds gathered in chorus.

This was in the night of the late spring. The air was cool but had begun to sense summer. The bird’s call was returned by a cry from the ruins, a single note that held itself for a moment and then faded away.

Peter Benson’s new novel

OUT IN AUGUST 2012

David Morris lives the quiet life of a book-valuer for a London auction house, travelling every day by omnibus to his office in the Strand. When he is asked to make a trip to rural Somerset to value the library of the recently deceased Lord Buff-Orpington, the sense of trepidation he feels as he heads into the country is confirmed the moment he reaches his destination, the dark and impoverished village of Ashbrittle. These feelings turn to dread when he meets the enigmatic Professor Richard Hunt and catches a glimpse of a screaming woman he keeps prisoner in his house.

Peter Benson’s new novel is a slick gothic tale in the English tradition, a murder mystery, a reflection on the works of the masters of the French Enlightenment and a tour of Edwardian England. More than this, it is a work of atmosphere and unease which creates a world of inhuman anxiety and suspense.

978-1-84688-206-7 • 250 pp. • £14.99

Winner of the Encore Award, a trenchant critique of modern civilization, describing how one family’s tropical heaven becomes hell.

978-1-84688-192-3

144 pp. • £8.99

Winner of the Guardian Fiction Prize, a lyrical portrait of the landscape of the Somerset Levels and a touching evocation of first love.

978-1-84688-191-6

160 pp. • £8.99

Winner of the Somerset Maugham Award, a novel exploring the evolution of an unlikely relationship, in a beautiful countryside setting.

978-1-84688-193-0

144 pp. • £8.99

A compelling tale of surfing and coming of age, and an intense examination of a young man’s struggle to establish his identity.

978-1-84688-195-4

192 pp. • £8.99

The gripping tale of a quiet and solitary private detective whose uneventful life world spirals into a circle of chaos and death.

978-1-84688-196-1

192 pp. • £8.99

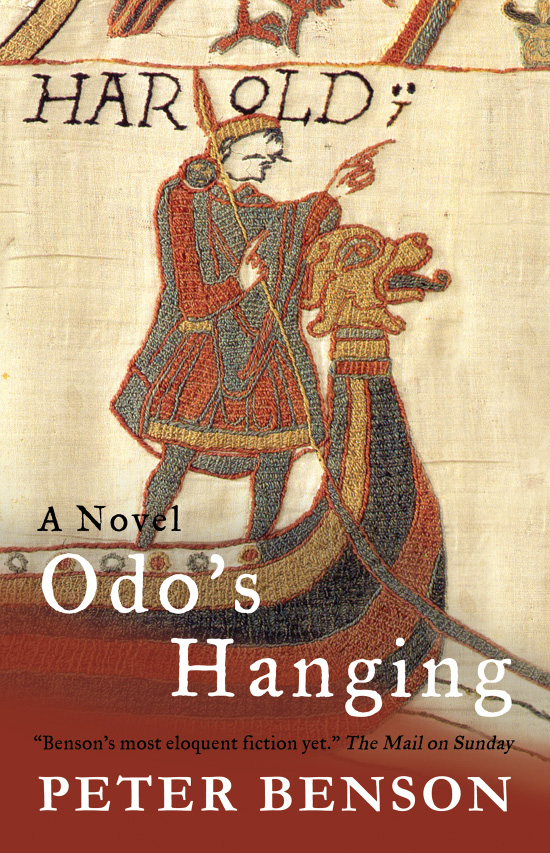

Weaving in the dramatic events portrayed by the Bayeux Tapestry, an absorbing novel which brings to life a fascinating period of English history.

978-1-84688-194-7

240 pp. • £8.99