CHAPTER NINETEEN

Eating Dirt

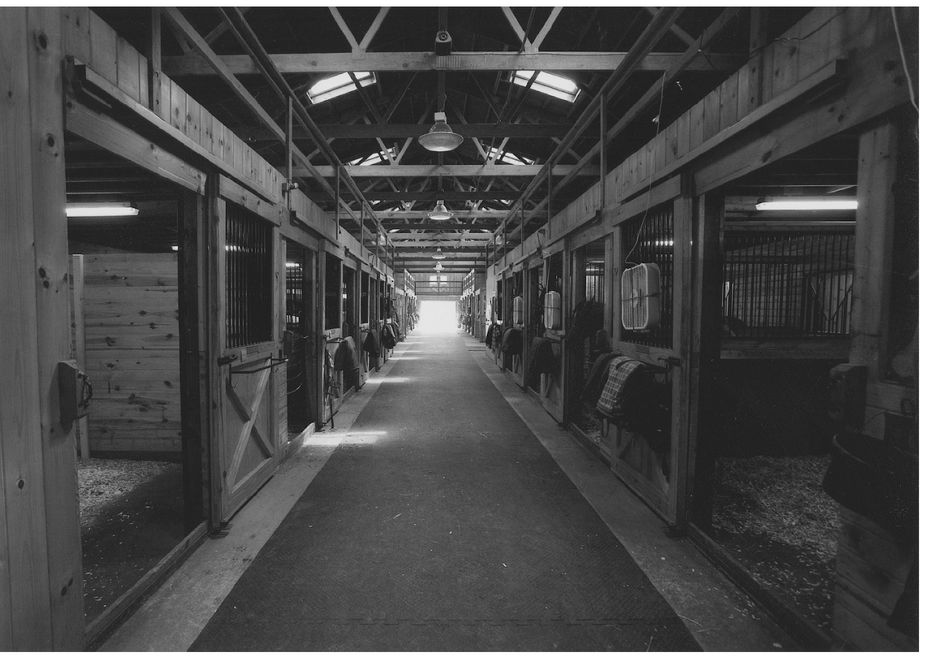

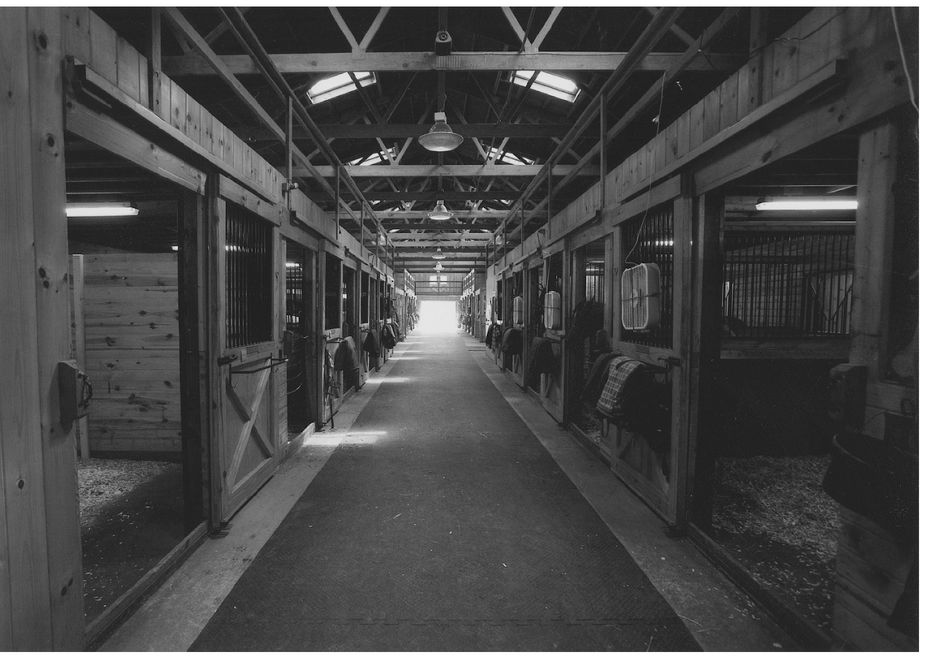

IT STRUCK ME AS SOON AS I ENTERED THE BARN: a sense of unease, a frazzled energy, a whiff of panic. Bobbi is never anxious around horses, at least not noticeably, but there she stood, next to Willy in the cross ties, her hair matted down from the sweat of a recently removed helmet and a flush in her face. Elliot gave me a “Hi, Mom,” and a weak smile. Then I noticed that Bobbi was putting on Willy’s bridle, signaling she was behind schedule.

Cleo had a sore tendon from mixing it up in the fields with her buddies, so the plan was for the kids to ride Willy at one o’clock, Jane first then El, while Scott and I lunched at The White Hart. I would ride at two, preferring to ride without the kids around. I worried about their horseplay: nothing like Jane in tears from some barn-related mishap to raise my hackles. I had to keep my cool, especially today. Eight weeks had passed since I had been in the saddle. Various ailments were to blame. On spring break vacation in Anguilla I had whiplashed my vertebrae showing Elliot how to dive from a springy board, not unlike the one I grew up with and which, no doubt, duped me into believing I was eight years old again. I had also nursed an endless cold, courtesy of my germ magnets Elliot and Jane back at school, and had undergone a nasty surgery to correct a long-deviated septum. To be honest, I had welcomed the break. I thought I loved riding, and I wanted to master this horse business, but the learning, the Bandicoot, and the horse farm in general had drained me nearly dry.

Since my first fall in summer, I had been dumped again in our own indoor ring over the winter. Bandi shied at the door during a trot, twisted left and bolted while I flew right, pretty much a rerun of my first airborne performance. I landed delicately, though the footing is never as soft as one wishes, and immediately I got back on. It traumatized me less than the first time, but not by much. Now I have had eight weeks of not riding to dwell on it.

But the beautiful early spring day meant an outdoor lesson—no spooky doors in sight.

“We’re running a little late,” Bobbi said nervously as she finished tacking up Willy.

“Oh.” I said, disappointed because I had rushed through lunch, much to Scott’s annoyance. “Did your morning lessons run long?”

“Not really, but Nancy wanted to finish up with a ride in the field, so Angel and I went with her. I hated to cut her short because she is such a great boarder.”

This was true. Our very first customer, Nancy had been unfailingly excited about the barn, complimentary even in the midst of the ongoing construction. She and Bobbi had succeeded so much with Chase that they were on the lookout for another horse. One owner with multiple horses is ideal business-wise—reduced traffic on the road, fewer personalities to deal with, less human congestion on the property. Although technically a for-profit enterprise, we wanted to preserve the atmosphere of our own personal space and keep it low-key for people we liked. Breaking even would be enough, but hemorrhaging money forever was still a possibility if we didn’t keep our business heads. Nancy had recently acquired enough skill and nerve to canter Chase out in the open field as opposed to the ring. I envied her progress and was thrilled on her behalf when Bobbi boasted about her cantering around our large hay field, not once but twice without stopping. I wouldn’t have begrudged her the extra time either.

“We also had a little accident with Janie,” Bobbi continued.

I heard Jane cry “Mommy” in distress from the tack room.

“What happened?” I asked, blanketing the sparks in my brain.

“Angel stepped on her foot,” Elliot reported.

“I think she’s fine,” Bobbi added. “She’ll be bruised, but she’s moving everything, and we’ve put Cleo’s leg icepack on her.”

I jogged to the tack room, where Jane burst back into tears upon hearing my voice. Above the din, Jane’s sitter Marie quickly assured me she’d been up and laughing a minute before. Timing is tricky for parents, and it’s not uncommon for kids to re-fall apart when their safe emotional outlet appears.

“Poor Janie,” I took her onto my lap and kissed her head. “Did Angel step on your little hoof? Let me take a look.”

Marie had just gotten Jane’s riding boots back on, hoping to encourage her to ride and take her mind off the pain. But the boot seemed tight, and I removed it to view the damage. The swelling was minimal, and Marie pronounced the bones sound. But Jane gained a fresh sympathetic audience and couldn’t rally—it certainly must have hurt. We all recounted our episodes under the hooves of horses, but besides her tiny, more vulnerable feet, she also lacked her usual resilience due to a stomach virus she had weathered only two days before.

We prescribed rest and with an exaggerated groan I hoisted her up for a piggy back ride to the car. Homeward bound she brightened at the prospect of elevating and icing her foot in front of Dumbo and Madeline videos. Poor Jane: so often in tears at the barn. That her kinship with the animals made up for the occasional maiming amazed me. I gave her credit for savoring the fun and forgetting the injuries. Like her father and brother, and decidedly unlike her mother, she is a glass-half-full kind of gal.

I stayed behind to watch Elliot ride and to ready Bandi for my belated lesson. Pausing ringside, I saw Elliot comfortably confident on Willie who he had ridden only once before.

“Whoa, Elliot! Slow down that trot,” Bobbi instructed. “Willie’s turbocharged today.”

Bobbi later told me she found Elliot’s ride hair-raising due to Willy’s uncharacteristic burst of energy.

“I noticed he was getting a little stiff, so I put him on glucosamine. With this supplement they advise upping his grain some, so Willie is raring to go. I’ll have to cut him back.”

Grain is a “hot” food and pumps the horses up with an energy boost, a caffeine kick of sorts. There is no end to tinkering with a horse’s diet, including natural supplements that calm, some of which we had given Bandi. He didn’t spook less, but he grouched less during grooming and tolerated cuddles better.

Elliot itched to canter Willy. It went well, if a bit fast, and Willie’s big canter surprised Elliot after Cleo’s delicate stride, illustrating that no two horses ride alike. Later, Bobbi rethought her decision to let him go for it. After Janie’s encounter with Angel’s hoof and her recent first fall, not to mention my own wobbles, Bobbi needed a break from the Bok family having adventures.

Finally my turn, I rode Bandi out to the larger ring while Elliot finished up in the adjacent dressage arena. While Bobbi, Elliot and Willy headed indoors to untack, I practiced my trotting and circles, alone and without trouble. Starting solo was risky after such a long break, but a bike ride with Scott beckoned, and I was striving to keep our relationship intact, temporarily filibustering Scott’s objections to my time sink of a new pursuit.

My skills rusty, I nevertheless enjoyed Bandi again. I re-appreciated his familiar trot and even canter. Keeping him energized required steady effort, and the work strengthened my legs and kept me focused and accurate with my commands. Bobbi had recently suggested I try spurs and a whip for my lazy boy, but I was determined to muscle my will through my body to get what I wanted from him. Bobbi could do it, so it wasn’t impossible. I tired quickly, but it felt a purer form of horsemanship. And I was still somewhat idealistic.

On a short break between canters, Margaret Ann strode into the ring. A horsewoman we knew from Riga Meadow, she also sold tack and gifts and dropped by to firm up plans for her kiosk at our upcoming June show.

“Hi, Margaret Ann,” I greeted. “I’m almost done, maybe ten minutes, and then Bobbi’s all yours.”

“All right, take your time. I’ll just sit on the bench here if you don’t mind.”

“You might get a face full of dust, but you’re welcome to it.” Thanks to Kenny, our ring drained almost too well, requiring copious watering in dry weather.

A teak bench divided the two rings. Margaret Ann settled down and I confidently resumed my trot, playing to my impromptu audience.

“Energize that trot before asking for the canter,” Bobbi instructed. “Get him paying attention. Now sit the trot tall and left leg asks for the canter.”

I had trouble keeping my butt heavy in the saddle against the trot. Only in attempting this motion did I realize how natural posting is. But if the horse feels you posting he should not, and generally will not, pick up the canter unless he is particularly generous. My usual methods of cheating included standing a little in the stirrups to keep my bouncing cheeks off the saddle altogether or leaning forward and pushing the reins forward—“Giddy-up, cowgirl” Bobbi generally joked—to make up for my weak seat. Against type, Bandi picked now to show off a too lively trot when I needed him to slow down. He’s a wily character.

“Remember, the hands don’t make him go, your seat and legs do. You and Elliot do exactly the same thing—flap your arms to get him to go. Yee-haw!” She chicken-winged her own elbows dramatically. “This cowboy stuff won’t work. Organize yourself again, slow down the trot—not too slow—sit tall, hands give the reins slightly forward but quiet, and ask him again.”

This time I managed it and cantered down the long side of the ring. As I approached the bench and Margaret Ann, Bandi startled, stopped short and simultaneously jumped sharply to the center of the ring away from Margaret Ann, whose entrance and presence he had distinctly noted and who we had already passed at a trot several times. She had not appeared out of thin air, nor had she been transformed into a horse-eating monster. Off I flew landing with a thud flat on my back just under Bandi’s left shoulder. He didn’t bolt this time and high-stepped to avoid trampling me while I scrambled out of his way up onto my feet. Bobbi ran over.

“Are you okay?”

I considered.

“Yes. I think I’m fine.”

Unhurt, but mad. I grabbed a hold of Bandi’s reins and shook his face. “Bandi! What is the matter with you? Stupid horse; don’t you dare do that again.”

Brushing myself off, I asked Bobbi, “Where did I go wrong?”

“Not your fault. I saw him get the hairy eyeball, but he was too quick for me to warn you. He didn’t really spin, but jumped to the side. I thought you were going to stick it at first, but then sometimes it’s better to bail.”

“It was rather controlled and graceful,” Margaret Ann said, “a slow motion ejection.”

It did have that feel about it, even to me, but still I railed at having been unseated again, at a canter no less.

“Could I have stayed on?”

“Probably if you had had a little more right leg on him to curve his body away from the bench, the weight on your right would have balanced you when he jumped right.”

“But wouldn’t that be pushing his middle into what he feared, making it worse?”

“The idea is to curve his center body toward the spooky thing and his face and hind end away. They’ll always spook away, so by curving his body like a C you not only remove his eyes from the object, but impair his full ability to jump or spin in that direction.”

Sensible, I thought, but I despaired at a weight shift that was one more thing to think about on top of a perpetual consciousness that Bandi might spook at anything, even the benign Margaret Ann, or the tractor lying in wait at the edge of a field, or a rogue daytime deer, or the giddy gymnast chipmunk, or the swooping crow, or the angry wasp, or the bloodthirsty horsefly, or the revving motorcycle, or the visitor who knows nothing about horses, or the car alarm in the parking lot, or the terrifying thoughts that flit around his small, highly imaginative brain, or, or, or . . . Toby even spooked at the sight of Cleo simply lying down in her pasture one day; she must have posed an unusual silhouette. He just flipped tight around and tracked for the hills until Bobbi, brave woman, forced his quivering, agitated fifteen hundred pounds right up to the fence where Cleo was sunning her belly.

“Look, Dumbo! It’s only Cleo,” I heard her urge.

He snorted his panic and danced an eight-step in place, Bobbi not allowing retreat. As Bandi and I were alongside at the time, forcing a false calm I u-turned toward the barn, leaving Bobbi to fend for herself. I was the last thing she needed to worry about. Bandi couldn’t have cared less about Cleo’s lounging aspect, miraculously discounting Toby’s agitation, so we avoided trouble. I gave myself some credit for keeping a cool head and making a good decision.

As in life, with riding there is always something. The trick on a horse is to develop good reflexes, catch spooks early and be prepared for anything. There are no assurances in this business. Shit happens, and even if you could hermetically seal your horse environment from all possible outside influences from bugs to tractors, you’d have a totally neurotic horse who would still, I’d bet good money, find something to get loopy about. The horse term “bombproof” is silently qualified by “within reason”: the horse’s “reason” that is, not the rider’s. Conditioning to all conditions is the lofty goal, but some horses never adjust to the things that scare them. A slant of light striping the indoor ring; a rush of wind that rattles the barn door; the harried whinny of your horse’s buddy out in the field—all unpredictable and sometimes disruptive, sometimes not. I have searched for the science of this, the logic, and believe me, it doesn’t exist. The only defense is a dual personality: my riderly self must stay loose, calm and relaxed to confer a sense of ease to my horse, but at the same time sit constantly AWARE, prepared for anything and everything, from the postman filling the mailbox to the cougar my horse imagines crouches in the brush as I meander, whistling a happy tune, along a wooded verge. Does this disrupt that dreamy, glamorous, magazine-quality image I stubbornly keep in my head? Well, ’er, a wee bit, yes.

“If it were easy, it wouldn’t be as much fun,” Bobbi liked to quip.

I guess so. But I hanker after that fantasy. Perhaps once my skills improve, I can enjoy my ideal ride, at least for a few nanoseconds of each experience or maybe once a year on my birthday.

So, I scolded Bandi since Bobbi repeatedly had advised me to get mad instead of scared. A rough day for her: first Jane’s foot, then Elliot’s speed date with Turbo-Willie, and then her boss flying through the air without the greatest of ease. Bobbi placed her arm around my sagging shoulders, made sure I was okay, and asked if I wanted to get back on. That depended on the definition of “wanted;” simultaneously I thought, I know I should, and hell no, but responded “yes” with shaky conviction. I wrangled my foot high into the stirrup, grateful for no back or hip twinges, and, with a leg hoist from Bobbi, swung my dusty, dumped self up and across tense Bandi’s rippling back.

“Alright, Bandicoot, you rat, let’s get with the program, boy.” I tried to lighten my mood.

“Ready to try that canter again?” Bobbi probed as she returned to the center of the ring.

“Sure.”

“Should I move?” Margaret Ann rose from the bench.

“No. You stay right there, as you were,” Bobbi commanded, determined to see me and Bandi through this trial.

This is like parenting adults, I thought, remembering how many times I had helped my kids through a scary dream, climb a tree, or jump off our boat into the dark lake water. No matter how much you’d rather, you don’t give in, but muscle them through, because therein lies the path to CONFIDENCE . . . or is it that deep-seated fear from which they never recover?

Bandi knew he was in the doghouse so we picked up the canter easily. As I headed for Margaret Ann on the bench, I concentrated on Bobbi’s instructions so much that my brain ached.

“Keep your right leg on him and push his belly toward the bench. Let your weight drop into that right stirrup. Bend his head right away from Margaret Ann and keep him going forward. Make him focus on your commands.”

My rising panic turned my head and body hollow.

“See his ears? They’re turned toward you, but still up. This is good; he’s listening for your instructions. Leg on, leg on... a little right rein . . .”

We passed the scary visitor without incident.

“Good girl,” Bobbi called out. “Now ride him on, keep him going. Think gallop.” Speed was the last thing I wanted more of. “Use your seat, give him some rein and look where you want to turn, then, when you’re ready, ask him to trot,” she continued.

Upon Bobbi voicing “trot,” Bandi broke the canter without any command from me. Great, I thought, he understands English but believes in monsters. Bobbi sometimes spelled out the commands, like you’d do with a child. I haven’t yet met a horse that can spell, but I’m sure one exists. Shit, I said under my breath; I knew what was coming.

“Was that your transition or his?”

Oh, how I wanted to fib.

“His.”

“Okay, canter again and bring him down to a T-R-O-T on your command, not mine.”

The next time we got it right—a canter past Margaret Ann twice around, followed by a smooth transition to trot and then to walk, on my terms. We took this tender mercy. A glimmer of confidence mingled with my disappointment at not sticking the spook. My third time in the dirt had been easier than the first two, despite my faster mph. Maybe the horsey adage was true—you’re not a rider until you’ve come off at least ten times. Three down, seven to go.

Scott and Elliot had been wandering through the fields and missed my little drama, but I fully disclosed it later on our bikes hurtling (fearlessly now, thank you Bandi; bikes are so much more controllable), down Weatogue Road. At home that evening we nursed Jane with ice and sympathy. A blue-black hoof shaped bruise spread from her ankle, across the top of her foot, seeping down between her toes. She hobbled two days, but relieved us with steady improvement. “We should have taken more care: the parents’ old lament. Scott and I re-vowed to fix at least one pair of eyes on her at all times at the farm. While Elliot and we were acutely aware of the evident dangers and better intuited the language of horses, Jane still basked in a state of taken-for-granted protection. On the one hand, guarding her safety was our responsibility until she caught us up on the learning curve. On the other, with her jump-start in horsekeeping, in expertise she will lap us in the end, and, if Bobbi is right, easy equals limited fun.

Circumstance postponed my next rendezvous with Bandi. The subsequent weekend our family missed Salisbury altogether, heading to Philadelphia for Scott’s and my twenty-fifth college reunion. The kids were excited about the train, the hotel, and a hotel-supplied babysitter, a new experience. Jane’s sense of adventure and romance came to the fore.

“You and Daddy met here?” she asked again and again as we approached the block of high rises at the west end of the University of Pennsylvania campus. We pointed our fingers toward the sixteenth floor of High Rise North. Elliot squirmed and rolled his eyes.

“Yes we did honey, on the very first night that Mommy moved into the school.”

“Act out how you met!”

Scott and I smiled remembering our introduction twenty-seven years ago, mere babes at twenty years old. We also winced at how fast all had gone since.

“Well, I can’t remember exactly, but Daddy’s roommate invited me over to meet some of the people on the floor. Daddy walked in, wearing a suit and tie having been campaigning for the first George Bush, and by midnight we were all singing and dancing with lampshades on our heads.”

“Lampshades? Why lampshades?”

“I know it sounds silly, but it was something we did back then to have fun.” I winked at my perplexed daughter.

“From then on, Mommy and I hung around a lot together, going to basketball games and downtown into Philly to see things like the Liberty Bell that we’re going to see later,” Scott added, with nostalgic eyes.

For Elliot we reenacted our chants including “Sit down, Pete!” whenever our arch rival Princeton’s basketball coach ventured up off the bench. The Palestra was a great place for ball, and Scott and I fondly remembered stashing our books in Rosengarten Library, only to collect them just before closing at 2 a.m. after a game date, complete with a late Double-R-Bar Burger at Roy Rogers and a long stroll through a moonlit Center City. As an insecure transfer from Monmouth College in New Jersey, I also recalled Scott’s kind support as I sweated my initial grades at Penn.

The story of my path to Penn and our marital destiny is known to many of our friends though not to the kids. I had been commuting to Monmouth College and dated a classmate. It was a serious relationship, and Andy suggested we should spread our wings. We applied to NYU and Penn. I was accepted to both, and Andy to NYU. Selflessly, he persuaded me to take the Ivy League opportunity (though I barely knew what the Ivy League was). I went off on my own amidst sworn promises of fidelity. Always homesick as a kid and reluctant to venture far from home, some cosmic force propelled me west toward a deeply satisfying education and also to Scott. Just a few weeks after I arrived, I “Dear John”ed the much-too-good-for-me Andy and a twenty-seven year relationship began for Scott and me. I sincerely hope Andy found someone worthy of him. As one friend said, “You owe a lot to that guy.” And so I do.

My two weeks’ riding reprieve, courtesy of the Penn reunion, was welcome given my latest fall from the Bandicoot. Fruitlessly I used the time to obsess: is this really for me if I’m so relieved not to ride? But spring had fully arrived in our absence: the farm radiant in May’s monochromatic fashion show of pale to deep greening grass and unfurling trees swishing against too-blue sky, my back and nose fully healed, and my immune system strong again. Bandi and our bursting-with-life trails beckoned like a siren’s call.

BOBBI RUSHED BACK from a show Saturday late afternoon of Memorial Day weekend so we could ride. I had a test to learn for our dressage show. After my first pre-show experience at Riga Meadow, I couldn’t muster much enthusiasm, but Bobbi summoned enough for us both.

“You’ll be fine,” she assured. “It couldn’t be any more comfortable, our own show at our own barn, totally familiar territory for you and Bandi.”

I wondered how a show at my horse’s home could be advantageous now at Weatogue Stables and yet was disadvantageous at Riga Meadow, and I concluded Bobbi manipulated the facts toward my greater comfort. But Jane was excited without really knowing why, and once I told a reluctant Elliot that his Cleo really wanted him to show her, he readily agreed, not questioning my pony language powers. Like Bobbi did with me, I was not above manipulating my kids for their own benefit, or for mine for that matter.

I like dressage. Introductory level A and B require walking and trotting a set test pattern, hugging the wall or fence, transitioning smoothly between gaits, changing rein (or direction), circling evenly, stopping squarely and saluting the judge. Sounds easy, but you can spend a lifetime perfecting the intricate details of a seamless, elegant connection between horse and rider. A perfect circle with good form is harder than it sounds. The rider appears to just sit and take the ride: still hands, motionless legs, perfect upright balance of a graceful body void of busy maneuvering. Slight shifts in weight, eyes and thoughts, and wiggly fingers project a seemingly telepathic communication. An equine puppeteer, the dressage rider strives for invisible strings. Done expertly, the judge barely sees commands and simply enjoys the results.

I appreciate the quiet, measured pace of dressage, and the solitary act of me, the horse, a judge and a score. Of course that means judging eyes are on one rider at all times; she’ll not miss any mistakes. Placement accrues from accumulated points against a tough standard calculated as a percentage of 100, rather than your ride rated against others alongside. Anything in the 50–60% range is good, 70s get rare, and you want to avoid 40 or below which signals incompetence, a possible risk of injury to the horse, so much so that the judge can actually excuse you: a slam-dunk of embarrassment. If you can avoid that, it is mostly a civilized one-on-one, the only free-for-all occurring at the warm-up when riders share the practice area. But because there is no jumping and because each test concerns one rather than multiple riders, even this progresses sanely.

My hardest task would be keeping my mouth shut. Points are deducted for talking to the horse or clicking the tongue, which I tended to do on a continuous basis at the trot in a vain attempt to keep a steady rhythm. I was a human metronome.

“Remember: no clucking,” Bobbi warned.

“OH. Right,” I said, getting right back to it after one pass, “Cluck, cluck, cluck.”

“Bandi, tell your mother to be quiet.... Bandi says ‘be quiet, Mom’.” Bobbi was now talking both to and for my horse, a veritable equine ventriloquist.

“I can duct tape your mouth,” Bobbi suggested.

“Maybe if I chew some gum.” I pursed my lips into a cramp.

“Cluck, cluck, cluck.”

“Just think whip instead of mouth if he needs some energy.”

“Can you tape my ass to the saddle while we’re planning props?”

After a few silent minutes: “cluck, cluck, cluck.”

I bit my tongue through the test course a few times, feeling accomplished and eager, for once, to return the next day and hack away at it some more. Multi-taskers, welcome—about six or more maneuvers must occur at once, in varying combos: pressuring one or both legs into Bandi’s sides, edging one back or forward, not too much, turning one or both feet to employ a spur, or not (just as difficult), shoulders back and down, half-halt with my outside hand (that one rein squeeze and release that keeps his attention), flex the ring finger of my inside hand (or is it the other way around?), reins taut but giving, elbows relaxed (yeah, right), hands at the withers, thumbs up, no unintentional tickling with the whip but no rapier flailing either, no crossing over the reins to adjust for poor lower body action, ugh—(that last circle was an amoeba), left seat bone down, heels down, weight into the right leg, shoulders back (I revert to Quasimodo style ASAP), strong belly forward, oops—missed that corner altogether, sit heavy, loose hips, tighten thighs, no—loosen thighs, change the whip gracefully to my inside hand, no sound effects . . . oh, and my old favorite, look where I want to go. Following the course requires enough intensity of focus to edge out any concern about spooking or falling. The concentration freed me. I toted the test score sheet back to NYC to memorize it, all fired up now about the show, thinking less often about scratching at the last minute. I did not tell Elliot that he and I might compete against one another. This was getting interesting.

After my first official dressage lesson, Bobbi, Angel, Bandi and I headed out for a trail ride in the late afternoon sun. The day ended steamy as New England’s moist spring often invokes summer’s heavy heat; only last week we feared frost would harm my family’s incautiously planted zinnias, delphinium, foxgloves and tomatoes. We lazily followed the farm’s dirt road watching Chase and Q run flat out around their paddocks, bucking, jumping and farting so that the ground shook under our feet. Their wild speed and agility both awed and terrified me, such powerful otherness that we somehow collect and tame—almost, but not quite—that plainly broadcasts horses’ retained freedom and strength. I’d rather not see what they can do in their natural state. Can they reliably sublimate those instincts when we’re on their backs?

We turned onto the wide path that Meghan had mown through the high fields, the hay already ripe for the season’s first harvest. Winding through two fields and woods, around the seventy or so acres, we enjoyed the undulations of green-to-golden grass in the sweeping breezes. Birds took wing out of the meadows, swooping to stitch crazy patterns of blue sky and white clouds. Bandi and Angel relaxed on an outing that didn’t require concentration or ring-defined circling. Angel’s swift walk prompted lazy Bandi and me to trot occasionally to catch up. I chatted loudly to Bobbi, my method to flush any more birds or camouflaged deer and turkeys well before we got to them, but even the bugs respected our peace.

I appreciated this ride as “one of life’s wonderful moments” moment: out on my own trusty steed (well, sort of trusty), in a preserved field, on a farm approaching its beautiful apotheosis after more than a year of renovation and impatient questioning, will it ever be done? The dirt piles but a memory, all lumpy overgrown paddocks had been leveled off and were re-growing in various stages of baby grass, their tender blades peeking through the hay we laid to protect the seed. Ferns were feathering their tendrils and the trees, young and ancient, were popping open to full-domed shade umbrellas. My attuned senses absorbed every last detail of spring with almost paranormal awareness. Was green ever so verdant, the light ever so lucid? I floated, a light-hearted butterfly able on the breeze. The distant barn stretched long and proud, its fresh paint daring the wear and tear of a new chapter. Though we gratefully intuited Mrs. Johnson’s venerable experiences etched within the old grains of these barns and the furrows of these paddocks and fields, our history on this patch of land was yet to unfold; I rode poised between El-Arabia’s past and Weatogue Stables’ future. What stories await us? What adventures?

Loud neighing roused me from my reverie. In addition to Chase, we had recently welcomed two new horses who were playing in their paddocks: OneZi, a four-year-old gelding training under saddle and his sire, Royaal Z, a sleek, twenty-two-year-old black stallion. They both belonged to Sabrina, a keen equestrienne from distant Greenwich, who sacrificed proximity for full day turn-out and a large paddock over which her “boys” could hold dominion. Three more boarders were due. In the early days, Scott, Bobbi and I concluded “if we build it they will come,” and they have: lovely people and horses. With Weatogue Stables off to a fine start, I rode the land deeply moved by this rare, storybook experience. It is worth the fear, the falls, the hassle, the time management, the child worry, the spousal friction.

We rounded the bend and slow-poked home. Without warning and in an instant Angel leaped right and Bandi, in unison as if they were of one mind and body, did the same only higher and farther. A beady-eyed turkey head had popped up out of the tall grass inches from Angel’s feet and skittered noisily into the woods stage left. Bobbi and I both held on, and the horses quickly settled upon reassurance of hysterical fowl rather than that dreaded equinevour. Bobbi had mentioned earlier that Meghan sometimes encouraged Bandi to chase the wild turkeys from his paddock.

“Oh great, Meghan,” I teased. “Just what I need—a horse that races after turkeys.”

But Bandi didn’t pursue the panicked bird, and I quietly noted that each time Bandi spooked I settled just a bit sooner. During my first Bandi trail ride last summer, I awaited the worst, panic my only mode. Over time I still worried, but also inched toward acceptance of inevitable “challenges” out in the big bad world of unforeseen circumstances; and, as in life off the trail, sometimes you stay on, and sometimes you fall off. I counted my blessings that I stuck this time, and Bobbi and I congratulated one another. It goes against my nature to look on the bright side, but I did, and the psychology worked . . . some.

That night, drifting into sleep, I jumped awake in my bed, as we sometimes do when dreaming of falling. But this was a leap, exactly the sensation of Bandi spooking, and it happened three times before I finally trusted slumber. I shook off my inclination to label it a bad omen.