Introduction

Weather

As part of the Intermountain West, southern Nevada has a desert climate. The dry, clear air allows strong radiation cooling during the night so that temperatures often drop 50 degrees Fahrenheit by sunrise. Even the hottest areas generally have cool nights. But deserts aren’t the whole story. The highest mountains in southern Nevada reach nearly 12,000 feet in elevation. Because temperatures drop about 5 degrees Fahrenheit for each thousand-foot rise in elevation, this means the highest mountains are always cool, even during the summer. The high mountains also extract more moisture out of passing storm clouds, which means the weather can change rapidly from cool to downright cold, and high winds drop the windchill even lower.

Southern Nevada receives more than half its annual precipitation during the winter in the form of rain in the deserts and snow on the mountains. Spring and fall are generally dry. During late summer, moisture moves in from the southeast and thunderstorms may develop over the high terrain during the afternoons. When thunderstorms start to form, get off high peaks and ridges. Heavy rain from thunderstorms can cause sudden flash flooding in streambeds and dry washes. Stay out of narrow canyons during thunderstorm weather. Never camp or park a vehicle in a wash.

Protection from the heat and the sun is important. During the summer plan desert hikes early in the day, and wear a sun hat and use sunscreen. The thin air at higher elevations provides even less protection from damaging ultraviolet rays, so even though the air is cooler, the sun has even more of a burning effect than it does in the deserts below.

Geology and Geography

Southern Nevada is part of the Basin and Range geologic province, a vast inland area of isolated, parallel mountain ranges separated by desert valleys that covers all of Nevada and parts of the adjoining states. Basin and Range topography was created by movement of the North American and Pacific Plates, which are at present colliding along the famous San Andreas Fault zone in western California. When the Basin and Range country formed, stretching of the earth’s crust caused the underlying rocks to break apart along fault lines. The resulting blocks of rock sank to form valleys, and other blocks rose and tilted to form long, narrow mountain ranges, all trending approximately north–south.

The Spring Mountains, which include subranges such as the La Madre Mountains, are a classic fault-block range. Most of the bedrock here consists of layers of gray limestone, which have eroded into massive cliffs in the Lee and Kyle Canyon areas.

The striking terrain of Red Rock Canyon is due to deep layers of colorful sandstone, which generally lie below the older layers of limestone. This upside-down arrangement of the rock layers is due to several thrust faults, in which older rocks were forced sideways and over the top of younger rocks. Keystone thrust fault is easily visible from the end of the Keystone Thrust hike.

Petrified sand dunes, deposited back when dinosaurs roamed the earth and colored red by iron minerals, eventually became the sandstone formations of the Valley of Fire. Complex faulting and later erosion, primarily by water, created the domes and slickrock formations.

Flora and Fauna

Elevations range from 2,000 to nearly 12,000 feet in the area covered by this guide, creating a great range of habitats for plants and animals. The Mohave Desert, the driest and hottest of the four American deserts, is found at the lowest elevations, with widely scattered plants and animals. At the highest elevations the arctic-alpine life zone is even harsher than the desert, with short summers and hard winters severely limiting plant growth and animal habitat. As you progress up the mountainsides between these extremes, you’ll discover a rich and varied series of life zones, where plants and animals are found in typical associations with each other. These life zones do not have absolute elevation boundaries. Life zones merge into their neighbors, and such factors as steepness and direction of slopes and small-scale climate affect the distribution of life.

The Moenkopi Trail offers a sweeping view of the red and white sandstone of the Calico Hills and the somber gray limestone of La Madre Mountain above.

Indigenous Trees and Plants

Lower Mohave

Found from sea level to about 2,000 feet in this area, the Lower Mohave is dominated by widely spaced creosote brushes. Other plants include white bursage, yuccas, and saltbush. Prickly pear and barrel cactus prefer rocky areas. The Valley of Fire along NV 169, near the park visitor center, is a prime example of this life zone. Plants grow widely spaced due to the extremely limited water, and animals, including birds, are nocturnal or mostly active at dawn and dusk, when temperatures are moderate. During summer days the desert can seem devoid of animal life, but most mammals and reptiles are denned up in cool burrows or resting in the shade.

Upper Mohave

At elevations between 2,000 and 5,000 feet, the desert landscape becomes dominated by low sagebrush and blackbrush, which is found on the lower slopes of the mountains in southern Nevada. A classic example is the broad desert slope at the foot of La Madre Mountain and the Red Rock Escarpment, which is traversed by the Red Rock Scenic Drive. These tough plants survive heat and drought by shedding most of their leaves during dry periods. Other plants found here include yucca and barrel, cholla, beavertail, and hedgehog cactus.

Most of Nevada north of the Las Vegas area is high desert, where these plants dominate the landscape—the Great Basin Desert, a sagebrush ocean dotted with island mountain ranges rising a mile or more above the broad valleys. Different species of sagebrush occur from the valley floors to the tops of all but the very highest mountains.

Piñon-Juniper Woodland

Singleleaf piñon pine and Utah juniper are the main trees making up this pygmy forest, which covers slopes and mountainsides from about 5,000 to 7,000 feet in this area. The trees average about 15 to 20 feet tall, although piñon pine can reach 30 or 40 feet in favored locations. Piñon pines need a bit more moisture than junipers, so the piñons become more numerous toward the top of this zone. Growing within this open woodland you’ll also find cliffrose, Mormon tea, rabbitbrush, bitterbrush, and the occasional prickly pear and hedgehog cactus, as well as yucca. Mountain mahogany appears toward the top of the piñon-juniper woodland, and merges into the pine forests higher up the mountainsides.

Spring flowers grace the sand dunes near the start of the Rainbow Vista Trail.

Montane Forest

Marked by tall ponderosa pines, the mountain forest zone ranges from about 7,000 to 9,000 feet in southern Nevada. The long needles of these pines grow in bunches of three, and the bark of mature trees is yellow-orange. Older trees can be as much as 4 feet in diameter and reach 100 feet in height, although 50 to 70 feet is more common. As elevations increase, other conifers appear, including Douglas and white fir. Quaking aspen adds color to the highest parts of the forest, especially in the fall when the heart-shaped leaves turn shades of yellow, orange, and red, painting entire mountainsides with brilliant color. Upper Kyle and Lee Canyons in the Spring Mountains are classic examples of this delightful mixed forest. The mouth of Pine Canyon at Red Rock Canyon is a fine example of a microclimate, where cold air flowing down the canyon from the high country creates an extension of the montane forest well below its normal elevations.

Subalpine Forest

Timberline trees, such as these bristlecone pines, grow in low mats, which are often buried in snowdrifts during the winter, to protect themselves from the foliage-killing winds.

As ponderosa pines start to fade away above 9,000 feet due to the cold, alpine trees such as whitebark pine, limber pine, and bristlecone pine appear. This zone extends to timberline at about 11,000 feet. These hardy trees are marked by adaptations to the harsh cold and biting winds at the top of the forest zone, including the densely packed needles on the bristlecone pine and the flexible, snow-shedding branches of the limber pine. At timberline these trees grow in low clumps, sheltering in clusters or behind rocks and ledges. At the upper limit of their range, near timberline, the harsh conditions cause bristlecone pines to grow very slowly but in turn survive for thousands of years. The oldest tree on earth is found in the White Mountains just over the Nevada border in eastern California—the Methuselah Tree, a Great Basin bristlecone pine, is 4,851 years old.

Arctic Alpine

With the same climate as the polar regions of the planet, only low-growing plants can survive in the area between 11,000 and 12,000 feet. Lichen, a few grasses, and mat-like flowers such as phlox grow on and in sheltered areas among the rocks. But much of the landscape is bare rock and talus. The Mount Charleston Loop traverses several miles of this life zone.

Animals

The largest predator found in this area is the mountain lion, or cougar. Favoring remote mountain areas, mountain lions prey on deer and shy away from human contact. Most hikers are lucky to ever see a mountain lion’s track, let alone the actual animal. Although mountain lions are usually not dangerous to humans, attacks have occurred in areas where human development encroaches on mountain lion habitat. Some such attacks have involved dogs running loose. If you encounter a mountain lion, keep children and pets with you and make yourself as large as possible while backing away slowly. Do not turn your back on the lion. If attacked, fight back aggressively with whatever weapons you have.

Mule deer are common throughout the area and especially in the mountains. They forage on plants at dawn and dusk. Coyotes prey on jackrabbits, cottontail rabbits, and small rodents and have adapted well to human presence. Their wild yipping is symbolic of the West, and they almost always sound closer than they are.

Wild horses and burros are found throughout Nevada, descended from domesticated animals set loose or lost by early prospectors and travelers. The Red Rock Scenic Drive and the Moenkopi Loop Trail in the Red Rock Canyon area are good places to see wild burros. Cold Creek Road in the Spring Mountains passes through a wild horse range.

Paintbrush is a startling contrast against the early morning shadows.

Rattlesnakes strike fear into many first-time visitors to the desert. Found at all elevations except the very highest, the hazard can be minimized with some understanding of their habits. Rattlesnakes are cold-blooded reptiles and therefore are dependent on their environment to maintain themselves at a comfortable temperature. Contrary to popular belief, high temperatures quickly kill rattlesnakes. They prefer surfaces of about 80 degrees Fahrenheit. This means that they’ll seek out shade or old burrows during hot, sunny weather. On the other hand, cool weather sends rattlesnakes to warm, sunny places such as rock slabs. That tells you where to watch for rattlesnakes as you hike. Another factor is that rattlesnakes can only strike about half their body length, so you should avoid placing your hands within about 3 feet of possible rattlesnake hangouts, such as shady rock overhangs.

Usually, rattlesnakes sense your presence through ground vibrations and move off without your being aware of them. If you do surprise one, or get too close, the unmistakable rattle comes into play. Stop, listen, and locate the snake before moving away. Rattlesnakes are not aggressive and will not give chase. Finally, rattlesnake venom is not the deadly poison of people’s imagination. Very few victims die. The venom is tissue-destructive, and the snake’s fangs are loaded with nasty bacteria, so the main danger from a bite is a nasty wound and possible infection. Most rattlesnake victims are snake collectors or people who were playing around with rattlesnakes. All that said, any snakebite victim should seek medical care as soon as possible.

Rattlesnakes, like their nonvenomous relatives, are a vital part of the wildlife community. They eat rodents and other small mammals and help keep their populations in check. Never kill or attempt to handle rattlesnakes or any other snake.

Certain spiders, including black widow and brown recluse spiders, can inflict dangerous bites. Both spiders like dark, secluded areas such as brush piles or the bases of clumps of brush. Once again, follow the desert rule of not placing your hands where you can’t see them. Black widow spiders inject a neurotoxic venom, which causes difficult breathing and mild paralysis. Seek medical care if bitten. Brown recluse spiders aren’t life-threatening, but the bites tend to develop into nasty wounds that take a long time to heal.

You’ll sometimes spot tarantulas crossing roads or trails during their migrations. Although sometimes 3 or 4 inches across, these fearsome-looking, hairy spiders are not dangerous.

The most deadly animal, at least at lower desert elevations, is the common bark scorpion, although the main danger is to the very young or elderly. Once again, knowing their habits will almost eliminate scorpion stings. Bark scorpions come out to hunt insects at night, and spend their days clinging upside down beneath rocks, sticks, or bark. To avoid nasty encounters, never place your hands where you can’t see them, never walk around in the desert barefoot, use a flashlight when moving around camp at night, and always kick rocks and sticks over before picking them up.

Respect all wildlife by staying at a safe distance. Use a telephoto lens for photography. Never feed any wild animal. Animals get dependent on handouts, and then starve during the winter when their human benefactors are not around. So instead of helping them, you’re actually hurting wild animals by feeding them.

Birds

Although there are many species of birds in this area, some of the most common are piñon jays, which are found in large flocks in the piñon-juniper woodland. Their quiet peeping twitter is symbolic of the piñon-juniper woodland. These dusty blue birds forage for pine nuts during the summer and hide them in caches to use during the winter.

Ravens and crows are everywhere. These intelligent birds will eat just about anything, but they’re usually seen scavenging roadkill and food scraps. Red-tailed hawks are commonly seen resting on fence posts or soaring above the desert valleys and slopes, hunting for small rodents. Steller’s jays have a distinctive blue crest on their heads and can be heard noisily defending their territories among the tall ponderosa pines. Up among the bristlecone pines, you’ll see another jay, Clark’s nutcracker, which is hard to miss with its black, gray, and white color scheme. They are also known as camp robbers because of their bold attempts to score dropped food.

Prehistory

Current evidence shows that the first humans in Nevada arrived about 13,000 years ago. Large animals such as horses, elephants, and camels shared the valleys and the mountains with these early humans. Archaeological excavations at Tule Springs, about 15 miles northwest of Las Vegas, show that this was man’s first known settlement in Nevada, about 12,400 years ago.

There are three main panels and several smaller panels of petroglyphs along the Mouse’s Tank Trail. Petroglyphs are pecked into the rock.

The climate was much wetter 10,000 years ago than it is at present. Two huge lakes occupied the valleys of northwestern Nevada (Lake Lahontan) and northeastern Nevada (Lake Bonneville). In southern Nevada the forests extended much lower down the mountainsides, and the desert valley of Las Vegas was probably a piñon-juniper woodland. Fish, land animals, and food plants would have been much more plentiful then. With the relative plenty and milder climate, more advanced societies developed, especially along the ancient lakeshores.

Rock art dating from 5,000 to 7,000 years ago is common in Nevada, especially along migratory game trails and in areas where people once congregated. There are fine examples of petroglyphs (rock art pecked into the rock) along Petroglyph Canyon in Valley of Fire State Park.

When the Escalante-Domínguez expedition passed through southern Nevada in 1776, the Native Americans they encountered were Southern Paiutes. Nomadic hunter-gatherers, the Southern Paiutes traveled in small bands or extended family units of up to fifty people. Occasional bands would gather to form temporary villages of hundreds of people, especially in the fall in areas where the piñon nut harvest was good. But resources were too scarce to support permanent villages in the post-glacial Great Basin and Mohave Deserts.

History

The first non-native known to have entered southern Nevada was a Spanish missionary named Francisco Garcés. In 1776 he traveled up the lower Colorado River past the rock formations he named the “Needles,” a few miles south of the present town of Needles, California. It appears that he traveled a few miles into the very southern tip of Nevada.

Peter Skene Ogden, a fur trapper, barely made it into the northeast corner of the state in 1826. In the same year, Jedediah Strong Smith crossed the southern tip of the state and established a campsite near some springs in the broad valley east of the Spring Mountains. This camp, Las Vegas, would become a major stop along the Old Spanish Trail. He entered the state near the present town of Mesquite and traveled along Meadow Valley Wash and the Virgin River. Smith named the Virgin River the Adams River for John Quincy Adams, although the name didn’t stick.

Reports brought back by the early fur traders and explorers, although often inaccurate and embellished, increased the nation’s interest in the American West. The federal government sent a number of official survey parties to the West to explore and create accurate maps. In 1843 Captain John C. Frémont was sent west and began his explorations in northern Nevada. In 1844 Frémont followed the Old Spanish Trail westward to Las Vegas and then continued east into Utah via the Virgin River.

Frémont named many features during his explorations of Nevada, and came up with the term “Great Basin” to describe the intermountain area of the West, including nearly all of Nevada, that has no outlet to the sea.

Few emigrant parties crossed Nevada before the California gold rush began in 1848. When the trickle became a flood, most parties used routes across the northern part of the state, such as the Humboldt River, which has more water sources. The hazards of the route through southern Nevada were made famous by the experiences of the Manly-Bennett party. This group traveled a route north of the Spring Mountains, crossed the Amargosa Desert, and descended into Death Valley, where heat and lack of water trapped the main body.

Reports from the early explorers and prospectors made clear the potential for ranching and farming in the broad valleys of Nevada. Quite a few large ranches were established in the 1860s. Mountain streams and springs were diverted for irrigation, and the discovery of plentiful groundwater under many of the valleys led to the digging and drilling of wells. Most of the crops were grown to provide winter feed for livestock, though some human food crops were grown as well. Ranches had to be large, as the sparse natural forage required vast amounts of land to feed cattle. Much of the rangeland used by cattle is public land, and today the ranchers pay a fee to the federal government in order to graze their animals. Even today the major economic activity in fourteen of Nevada’s sixteen counties is ranching and farming.

The Las Vegas area was settled by Mormon expeditions sent from Salt Lake City. In addition to Las Vegas, Mormon settlers established a number of other towns in southern Nevada, including Callville on the Colorado River (now under Lake Mead).

As more people moved into the state, transportation in Nevada gradually improved. The trappers and prospectors mostly traveled on horse- or mule-back, trailing pack trains to haul supplies, furs, and ore. Emigrant trains generally used wagons pulled by oxen, though most members of the party usually walked. As mining camps and towns became established, the need for heavy transport increased. Freight companies hauled supplies and ore with heavy wagons pulled by a dozen or more animals (such as the famous “twenty-mule team”). The coming of the first railroad across the state, the Union Pacific of Golden Spike fame, in 1869 marked a revolution in travel. A journey that took weeks or months by horse or stage became a comfortable trip of a few days. Spur railroads were rapidly built to the major mining centers and settlements.

Nevada was originally part of the Spanish colonies in the New World, though the Spanish had little to do with the area. After the Mexican Revolution in 1822, Nevada was part of Mexico until the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 ceded California, Nevada, New Mexico, and most of Arizona to the United States. For a couple of years, Nevada was part of the Mormon “State of Deseret,” but Congress soon designated the Territory of Utah, which included Nevada until it became a separate territory in 1860. Nevada became a state in 1864.

The rapid population growth that made it possible for Nevada to achieve state-hood relatively quickly was caused in large part by the discovery of gold and silver in western Nevada. News of the rich Comstock Lode at Virginia City attracted a flood of prospectors, miners, shopkeepers, and teamsters, as well as more farmers and ranchers, who sold food to the mining towns. Since then mining has been a major part of Nevada’s economy, though the inevitable boom-and-bust cycle that follows changes in prices and world markets makes life unpredictable for mining communities.

Hoover Dam on the Colorado River, which was constructed between 1931 and 1936, was the world’s first large reclamation dam. Its primary purposes were to control the erratic flows of the Colorado River, which ranged from a trickle in late summer to raging floods during the spring snowmelt in the Rocky Mountains, and to generate electric power. It was this nearby source of cheap hydroelectric power that made the growth of Las Vegas possible.

Ponderosa pine is the largest tree in the Spring Mountains and is easily identified by its 5-to 7-inch needles that grow in clusters of three.

After 1945, tourism and gambling grew rapidly and are to this day a major part of the economy—especially in the Reno and Las Vegas areas. With the rise of Native American gaming in many states, Las Vegas has had to reinvent itself as a diverse entertainment center. Although most visitors come to Las Vegas for the casinos and the shows, a portion of those visitors seek out the nearby natural areas, as do locals.

Place Names

Although Native Americans certainly had names for all the geographic features with which they came in contact, the lack of a written language meant that the only means of preserving these place names was by oral tradition. Still, some Native American place names survived long enough to be recorded by European explorers. Among the newcomers who attached names to geographic features, as well as man-made features such as towns and roads, were the early fur trappers and explorers, emigrant trains, prospectors and miners, traders, stage and freight line operators, the railroad builders, and government surveyors, agencies, and officials.

Official place names, as designated by the US Board on Geographic Names and recorded in the Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) database, are used throughout this book. Local, informal names are used when there is no official name. The GNIS database is also the source for the summit elevations in the book. A recent resurvey of summit elevations using the latest advances in surveying methods has resulted in changes in many summit elevations. The result is that elevations shown on maps and mentioned in the text of this book are often different than the elevations used in older books and shown on US Geological Survey (CalTopox.com MapBuilder Topo layer; USGS) topographic maps.

Wilderness Restrictions and Regulations

At present, permits are not required for any of the hikes in this book, whether day hiking or backpacking. There are regulations specific to each area.

Spring Mountains National Recreation Area

Campfires are not allowed at any time of year within the three wilderness areas: Mount Charleston, La Madre, and Rainbow Wildernesses. Backpackers must use camp stoves. From April 15 to November 15, campfires are allowed only in fire pits and grills provided within USDA Forest Service–developed campgrounds. Motor vehicles are not allowed on trails within the NRA and are not allowed in wilderness areas. All litter and trash must be packed out or placed in trash containers. Historic and archaeological sites are protected by federal law and must not be damaged or disturbed.

Valley of Fire State Park

Campfires are allowed only in the grills and fire pits provided within the developed campgrounds. Dogs must be on leashes no longer than 6 feet. Motor vehicles are not permitted on any trail and must be operated only on designated roads. All litter and trash must be packed out or placed in trash containers. Plants, animals, and all other natural features as well as cultural and archaeological sites are protected by state and federal law and must not be damaged or disturbed.

Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area

Although the official name of the red rock cliffs at Red Rock Canyon is Sandstone Bluffs, the local and much more descriptive name is Red Rock Escarpment.

Camping is permitted only in the designated campgrounds. Campfires are allowed only in the grills and fire pits provided in the campgrounds. Motor vehicles are not permitted on any trail and must be operated only on designated roads. All litter and trash must be packed out or placed in trash containers. Plants, animals, and all other natural features as well as cultural and archaeological sites are protected by federal law and must not be damaged or disturbed.

About Wildfires

In recent years some of the mountains and deserts near Las Vegas have suffered a number of unusually large and destructive wildfires. While fire has always been part of the ecology in Nevada, a combination of drought, invasion by exotic grasses and other plants, tree-killing insect epidemics, and over-dense forests caused by more than a century of poor management practices has led to unusually intense fires not only in the forests but in the desert as well. Some of the hikes in this book have been affected by recent fires, and more will be affected in the future. Always call or e-mail the land management agency before your hike, or at least check their website, for current conditions and possible area or trail closures.

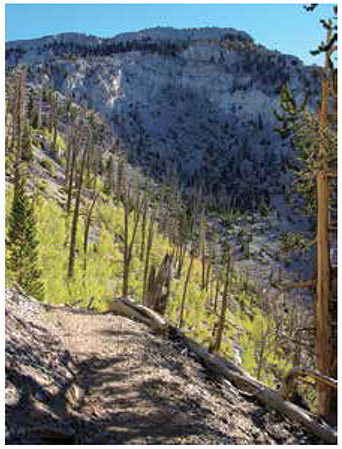

Quaking aspens are the first trees to return to an old burn on the North Loop Trail below Mummy Mountain.