PART 6

THE FIGHT OF HIS LIFE: JOHN’S POST-DIAGNOSIS BATTLE AGAINST CANCER

Before John was discharged after his first week of chemo, the nurses told Gina and Scott to make everything at home as sterile as possible. Gina’s mother and sisters came to the house and scrubbed every room from top to bottom. Nurses came to the house over the next two weeks to check on John, and he was very cooperative.

It was a tough few weeks after John came home. Lexie, only twelve at the time, had no idea what was happening as far as John’s care or his prognosis went. While Gina was trying to come to grips with everything, Scott wanted to take a family picture immediately. It did not turn out as well as he had hoped. “I just wanted something in case he died, because we didn’t have an up-to-date family picture, and I wanted a picture while he still had his hair.”

Meanwhile, John, wanting to keep as much normalcy in his life as possible, wanted to go to the Fourth of July parade in Midland, Pennsylvania. “He didn’t want to miss it because that was something that the family always did together,” Gina said.

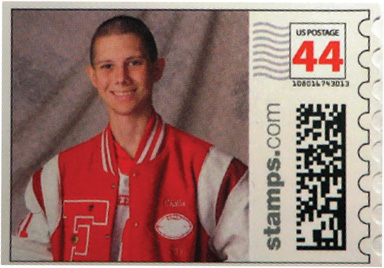

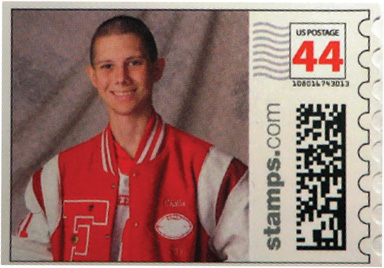

Football camp started in the middle of August, but John was unable to attend. While John still went to practice, hanging out with the team and riding around with Vince Sinovic in his golf cart, he was receiving treatment in the hospital when the team picture was being taken. He was so surprised when Coach Wilson told him to go to the picture studio and get his photo taken; the studio would Photoshop him into the team picture.

Scott told me how the Freedom Bulldogs football team, the coaches, and the parents always made John feel like he was part of the team. One particular road game provided a great memory. “We were playing an away game at Sto-Rox High School right outside of Pittsburgh,” Scott recalled. “John wanted to travel with the team, and we didn’t have a problem with it if the team didn’t. One of the team’s football mothers came up to my wife and me and said, ‘Wait ’til you see your son.’ We didn’t know what to expect. At the pregame show the Freedom team was coming out of the locker room, and here comes John out of the locker room with his brand-new letterman jacket. Most players have to wait until the banquet in January until they get their jacket, but since everyone knew John’s days were numbered, they gave it to him that night. He was so proud.”

John was trying to live his life just like his friends were, and that included making use of his new driver’s license. But because he was on so many different medications, Scott and Gina were scared to let him on the road. They ended up driving him to practice every day; then he would ride around the practice field with Vince Sinovic on the golf cart all afternoon. Then one afternoon in late August, John came up with an idea he thought would make things easier on everybody.

Scott recalled, “John came home after practice one afternoon and said, ‘Since you won’t let me drive, will you let me buy a golf cart to get around in?’ He said he would pay for it. Gina and I said, ‘You pay for it, you can do it—but if you get picked up for riding it on the streets, then that is on you.’ About two weeks later, John found one in the local newspaper’s classified ad section, so we went to look at it. He liked it, and the guy let him take it for a ride. John didn’t have any hair, and the guy recognized him from the newspaper story that Bill Allmann had written in the Beaver County Times. The guy asked me if that was him. I told him yes. He ended up giving John a nice deal on the golf cart and then told me to take an electric wheelchair he had in case we would ever need it for John. So I took that too.”

When the family got back from John’s Make-A-Wish (Alaskan cruise) trip in early September 2006, he had Scott take him to school. He told him that he would have to talk to Dan Lentz, the high school assistant principal, about setting up plans to do home schooling and to attend classes when he felt up to it. The reason John did this was that he was insistent about graduating with his class in June 2008. That day, from the outside looking in, John may have outwardly appeared down, but he certainly wasn’t lacking confidence that he was going to beat cancer.

Scott told me that although going to school was uppermost in John’s mind, it certainly wasn’t in his or Gina’s. “I didn’t care if John ever went back to school, because my wife and I knew the prognosis. We thought he had one or two months left at this time. Just the way the doctors said to us that if John was going to take his Make-A-Wish trip he better do it now.”

John, though, was insistent; he and Scott went into Dan Lentz’s office, where John again told him, not mincing his words, “I’m going to graduate with my class.”

Scott got emotional when recalling that, telling me, “There were a handful of things that choked me up about John, and that was one of them. He promised Mr. Lentz he would graduate with his class, and I will say this about John, his word was his bond.”

At the end of October, John received his second chemoembolization treatment. This treatment normally lasted an hour, and then John would be wheeled to UPMC Montefiore and sent to the Liver Cancer Center. Scott explained to me the logistics of him getting from one hospital to the other. Children’s Hospital, Presbyterian, and Montefiore were connected; John would travel many miles on hospital gurneys from one hospital to the other and then back again. He had to lie still for eight hours and keep his legs straight, but this type of treatment was so much easier on his body. There was no hair loss, and he was up and moving much faster than he was when he underwent conventional chemo. Gina would stay with him during every treatment. Having his favorite nurses, Maggie and Theresa, nearby always made him feel at ease.

Treatment for John and the family became routine, and by the third treatment, he had it down pat. His day would start out at four-thirty in the morning because he had to be at UPMC Presbyterian in Pittsburgh by six o’clock to check in. He would then report to the fifth-floor short stay area, where they would prep him for his treatment. It was important that he be given a lot of fluids through IV before his treatment, so he would have to lie down for four hours until he had received the correct amount.

Scott remembered how John became such a pro when it came to what went into his body that he knew all the medications and when he was supposed to have them. Once while he was waiting to go for treatment, the nurses started to wheel him down, and John said, “I didn’t get my Zofran pill.” The nurse said he had, but John insisted he didn’t get it, and he would not go anywhere until he got it. John made the nurse look in the garbage for the blister pack, and when she couldn’t find it, she still insisted he’d had it.

“Gina and I were getting a little embarrassed about it, but we both knew how John was, and he would know if he had it or not,” Scott said. After they had spent almost thirty minutes looking through garbage cans, the pharmacy called up and said that the pill they were looking for had never made it to the room. “The apology the nurse gave to John afterward was comical—she felt so bad,” recalled Scott.

John age 4 in the Challis family living room.

John age 3 in the Challis family front yard.

John age 3 with his Grandfather “Pappy” Tiberio at Kennywood Park.

John age 17 during Hunt of a Lifetime Trip in Baker City, OR.

John age 18 at the board during his senior project presentation.

John age 17 senior picture.

John on his golf cart after completing his wood shop project.

John age 17 at a Fourth of July picnic at his grandad’s house.

John age 17 at the final football game.

John getting “The Hit.” This is the only known photo of John’s famous hit, taken on a cell phone by Dan O’Leary.

John speaking at Walk for a Champion Fundraising event.

John and his Junior Prom date, Jackie Knopp.

John getting his nightly back rub from Gina.

John with deer at taxidermist George Sullivan’s.

John with Uncle Tom Challis.

John with Larry the Cable Guy backstage before show at Consol.

Family Picture when John received the Jeff Kemerer Award.

John with Mario Lemieux, John Smoltz, Ben Roethlisberger, and Pierre Larouche at 2008 Penguins playoff game.

John with Benjamin Jaworowski, Lexie, Anna Jaworowski, and Gregory Jaworowski at Jody Jaworowski’s basement.

Scott and John at Challis house driveway, waiting for Limo for Senior Prom.

John at graduation, hugging Vice Principal Dan Lentz.

Family picture on Graduation Day.

John leading the Tassel Ceremony after receiving diploma.

John sharing a proud moment with Gina after Graduation.

John with Lexie on hotel balcony at Myrtle Beach.

John with Steve Wetzel at Tinitique Café & Tavern, Beaver, PA.

John after receiving WTAE Athlete of the Week Award with Coach Steve Wetzel.

Before First Pitch at June 25, 2008 Game: The Pirate Parrot, Mike Tibolet, Adam Rose, John Russell, Scott, Steve Wetzel, Dan O’Leary, Lexie, Gina, John.

John with Joe Maddon of the Tampa Bay Rays.

John meeting with the Pittsburgh Pirates before June 25, 2008 game against the New York Yankees

John with Alex Rodrigues before July 2, 2008, game at Yankee Stadium.

John with the War Dogs Motorcycle Club delivering Stanley Cup final tickets.

John’s final public appearance at Conway Days, where he was named Honorary Mayor.

John with Mike White at Challis family house.

At graveside for John’s 21st Birthday, Joe Signore fulfilling John’s second request. From far left to right - Susan Lamping, Karen Ellis (adult), Mike Goedeker (white hoody), Anna Jaworowski (with white hat), Benjamin Jaworowski (red hat), Gina Farzati, Brad Brummitt, Joanna Jaworowski, Kristen Milanovich, Denise Divittis and Joe Signore

Front of John’s gravestone.

Freedom Post Office, dedicated to John June 2010.

John Challis 44 Cent stamp unveiled at the Post Office ceremony.

Bill signed by President Obama.

Heinz History Center display for John

Coby Johnson’s bedroom wall (8 years old), Berwick, ME.

The Challises received good news on November 7: John’s CT scan results showed that some of his tumors had decreased in size, both in his liver and lungs. This was the start of the many emotional roller coaster rides they would experience. The oncologists were very happy and said that even if there was no change, they would have been thrilled to see that the tumors weren’t growing or spreading.

Gina and Scott remembered one of John’s earlier treatments, where his potassium levels were too low and they had to give him an IV to increase the levels. “John was so upset because the nurses told him he was leaving at ten in the morning, and it wasn’t until after two o’clock in the afternoon when we left,” Gina said.

“I always said the worst thing the doctors ever told John was that he was in charge of his treatments,” Scott told me. “When John went back for more treatments after this time, he told the doctors and nurses, ‘If you’re going to check my potassium, you check it earlier, like at one in the morning, because I’m leaving at ten o’clock like you told me.’ John had Dr. Clark Gamblin (the head at the Liver Cancer Center at Montefiore) put this on his chart, and the nurses did this for him going forward.

“Another time it got to about a quarter to ten, and John still had an IV in his arm. The nurses were really busy, and John was so impatient that he started to pace the halls, hoping someone would notice he still had his IV in. When no one was coming, he decided to take out his own IV right in front of Dr. Gamblin. Blood started to shoot everywhere, and John got the attention of the nurses pretty quick. John was discharged right on time.”

As the holiday season approached, and with the future uncertain, John’s family and friends tried to make it his best and most memorable Christmas. When people asked John what he wanted for Christmas, he told them he wanted tools for the house he would have one day. John’s favorite teacher at Freedom was his woodshop teacher, Bert Pickard. He and John developed a great bond, and John really trusted and looked up to him. Bert taught John that a person could do anything with the right tool. As Scott recalled, “John lived with that philosophy until the day he passed, and he was saving tools for the home he would have someday.”

John loved Christmas and put up his own Christmas tree—one he had bought for his own future house, but he went ahead and put it up in the family’s basement. He also bought Gina a snowman ornament with all four family members’ names on it. That ornament still hangs on the family tree today. “I really have a lot of special memories of that ornament,” Gina told me as she thought back to the Christmas of 2006.

As 2007 started, John received another round of the chemoembolization treatment. Everything went well. Gina even got to sleep in a bed beside him that night instead of a chair. When he came home, he tried home schooling, attending Freedom only when he felt up to it. He was taking all of the classes that he needed to take to graduate—biology, algebra, history, and English—and he took woodshop from Mr. Pickard at home. John’s woodshop project was to build a storage box for his golf cart so he could carry his books and anything else he wanted to. All the teachers gave John homework, and when John had homework, Scott had homework. John tired easily, so Scott did a lot of his typing.

It had been over six months since his cancer diagnosis, and the Challis family was still getting used to their lives turning upside down. On top of everything else going on with John, Scott and Gina were fearful of a break-in due to the fact that they were storing so many pain pills and other medications in the house. In fact, Gina took to hiding some of the meds in three different parts of the house.

It was a very chaotic and confusing time for Lexie, who was then only thirteen years old. As she recalled, “I really didn’t understand what was going on at that time, after the first of the year [2007]. I didn’t understand why John’s medicine would make him vomit or why he would get really bad anxiety attacks.”

When John spent nights in the hospital, Gina would stay with him overnight, and Scott would stay at the hospital but come home to get Lexie ready for bed. She had to grow up quickly. “It was a combination of things,” Lexie said. “I didn’t really know what was going on with John, and I had to make sure I had everything ready for school, basketball, or cheering practice . . . remembering who my parents told me was going to pick me up from here and take me to there. It just all seemed a little crazy to me.”

On March 13, 2007, John’s CT scan showed that the tumor in his liver had gotten bigger. A week later, John received another chemoembolization treatment at Presbyterian. His last chemo treatment had been administered ten weeks before. In between there were doctor’s appointments and visiting nurses coming to the house several days each week, along with trips to the local pharmacy to fill John’s various prescriptions.

When asked by friends or neighbors how she was holding up during this time, Gina was very pragmatic. “Probably nine months went by, I think, and I started believing, okay, I have some time,” she recalled. “He’s dealing with it, he’s getting treatment. I remember somebody saying to me once, ‘Aren’t you tired of going for treatment?’ And my answer was ‘No, because as long as we go for treatment, that means he’s still alive.’ ”

After returning from his fishing weekend in April 2007, John wanted to stay busy, and he did so by preparing for his school’s junior prom in May. Even though Scott and Gina were nervous, it turned out to be a wonderful evening. “He went to the prom with his friend Jackie Knopp. A bunch of them got a limo, and all of John’s family and friends got to see him all dressed up. When John and Jackie came out for the grand march, they received the biggest ovation,” Gina said.

Scott and Gina were very nervous about John making it through the entire night, so Scott made arrangements with the Marriott, the hotel where the prom was held, to get a room for John in case he got tired and wanted to lie down for a while. The Marriott told Scott and Gina not to worry; they gave John a room at no charge and loaded it up with all kinds of snacks in case he got hungry. As Scott recalled, “It turned out John never went to the room, and when people were sleeping or napping in the corners, John just kept going.”

When John came home in the morning, Gina was awake (and very relieved). John wanted to stay up and tell her all about the whole night that he and Jackie had had. He told her he was already thinking about next year’s senior prom. Later that afternoon, after a short rest, John and Jackie and another couple went fishing and had a post-prom picnic. “Jackie was quite a friend to John,” Scott said.

At his doctor’s appointment a few days later, his scans showed that there was no change to his lungs, and that the tumor in his liver had shrunk almost one full inch. A week after, he had his sixth treatment, and it went well. A gel was put into his liver to keep the meds there, preventing them from affecting his kidneys. He came home from the hospital and received his regular fluids. He also had a pump for his pain medication (Dilaudid) this time. This recovery from treatment was his fastest ever. As Scott recalled, “We as a family started to really feel he was going to beat his cancer.”

With the new chemoembolization treatments, John’s hair had all grown back, and toward the end of his junior year of school, he attended a party at Taylor Dettore’s family farm. She threw a party for all of the kids she had met at Children’s Hospital. After their rocky start, she and John had become very close friends. Their conversations, as Taylor recalled, were deeper than the typical teenage conversations about school, friends, bands, or sports. “We’d talk about feelings that we really did not share with our parents or friends because we both had a reputation of being so strong and positive. Therefore at times it was hard, but we had each other,” she told me.

By the end of that summer, John had his senior picture taken, and right after Labor Day his scans showed no change to his lungs or the tumor in his liver. It was now time for John to pick what his senior project was going to be. This was a requirement to graduate at Freedom High School. He had no idea what to choose. He talked to Scott about it, and his dad suggested, “Why don’t you do something you know about . . . your cancer treatment.”

John loved that idea and went to Dr. Gamblin. He asked him about using his CT scans and how he could learn to read and explain them to people. Dr. Gamblin told John that whatever he wanted, he would get for him.

John was excited about his choice; he wanted nothing but a perfect paper. He continued to get his synopsis ready and didn’t waste any time getting all the information for his project. A week after starting the project, John had another chemo treatment for his liver tumor. He had Scott take pictures of him throughout the day—from the time he woke up until when he walked into UPMC Presbyterian for the treatment. Scott was not allowed to go into the actual treatment due to sterilization issues, but the hospital made sure John got the scans showing the chemotherapy drugs going into his liver.

He had new scans taken afterward, and these showed no change in his liver tumor, but they did show new tumors in his lungs. In addition, some of the original tumors in his lungs had grown in size. His recovery from this treatment was slower than usual, and he had more intense lower back pain as well. He had his fluids and pain medication pump for several days at home after this procedure. He went to physical therapy as he had done in the past, and he also started to see a chiropractor to help alleviate some of his back pain.

A year and a half into John’s diagnosis, Scott was still spending his lunch hours looking for new cures or treatments for cancer. He came across a drug called Nexavar. He researched it and even called the son of a man in California who was being treated with it. There was a grueling list of side effects, but overall this man’s dad had lived longer on this drug than doctors had expected.

Scott gathered all the information he found on Nexavar and took it to Dr. Graves. Five weeks later, Dr. Graves called Scott back and said, “Do you remember that drug Nexavar you sent me all the information on? I think we want to try it.” Scott told me about the pride he felt after Dr. Graves said this: “I was so happy; I felt like I was part of my son’s treatment.”

In November John’s scans still showed no change in his liver tumor, but there were new tumors in his lungs, and the existing tumors there were growing. He started with a full adult dosage of Nexavar. After ten days on it, he experienced many side effects, including loss of appetite, rash on his body, mouth ulcers, and pain in his hands and feet. When he stopped taking it the day before Thanksgiving, the symptoms went away. A week later he began taking Nexavar at a lower dosage.

John continued to experience severe back pain. Lexie and Gina would rub his back, which helped, but it was difficult for them to see him in such pain. He had bad anxiety and got worked up when his back ached. Lexie recalled one harrowing instance from that December. “I remember one time John and I were home together, and John had the worst back pain. His anxiety then kicked in to where it’s almost like he couldn’t control his feelings, pain, or breathing. I just remember lying in my parents’ room with him; I made it really dark and sat and rubbed his back. I was so scared. I know his medicine made him act the way he did, but that’s just one example of the side effects of cancer that not everyone sees.”

In addition to anxiety attacks, he experienced frequent nosebleeds, nausea, and mouth sores, all of which were side effects of the medication. Around this time he developed a real appreciation for tart or strong-tasting food. He loved blue Jolly Ranchers and the tartness of lemons.

As the holidays approached—notwithstanding John’s physical pain—Scott recalled there being an air of optimism in the family. “John’s Uncle Tom came in from Los Angeles with his daughter Kaitlin for Christmas, and I continued to think John was going to beat this. Christmas turned out to be great! Again all John wanted were tools and stuff for his house when he got one. John was always buying stuff for his house. He constantly would say to me, ‘When I get my house . . .’ ”

After New Year’s, John focused on his health and his goal of graduating with his class. He made it to school when he felt well enough, and on those days he always stopped to speak with Dan Lentz. Dan recalled how they used to talk almost every day, but John’s health was a subject that was never part of the conversation. “Johnny told me once he always liked coming in to talk to me because I never talked to him about the cancer. I always made sure to talk with him about something else. I figured every person he talked to asked about his health. So instead, we talked about basketball, football, girls, family, school, college, and so on,” Dan said. “I’d always make sure to tell him what a great job he was doing handling all of the attention, and what an impact he was making on everyone. And he’d almost always say the same thing: ‘I didn’t ask for this. I’d do anything to change it. But this is what God wants me to do, so the least I can do is make the most of it.’ ”

On January 8, John had routine scans done. They showed that the tumors in his lungs had grown. One nodule near the airway was large. There was no change in the liver. The doctors planned to increase his dosage of Nexavar.

That January, John went on a school ski trip to the Peek’n Peak Ski Resort in New York. Compromising her fear for John’s safety for the sake of his desire to live as normally as possible, Gina agreed to let him go on the trip. But it wasn’t easy. “I was so nervous. It wasn’t like we were five minutes from him,” she recalled. “John had to prove it to himself that he was still independent. John was the one who had to be in control. This was the first time John had gone away on his own, and everything went well on the trip. He had a great time with his friends.”

At home, John’s days and nights were backward. He napped all day and wanted to stay up all night. He had scans done in February, earlier than usual because the side effects from the Nexavar (headaches and a feeling of hardness in his stomach) worried the doctors. The scans showed no change in his lungs or liver. A month later, he went to Children’s Hospital’s emergency room because of a sharp, jabbing feeling on the right side of his abdomen. This was really the first and only time John ever went to the hospital due to a reaction, and they didn’t even keep him. His doctor, Dr. Graves, was doing rounds. He saw John, ruled out pneumonia, and checked his blood work. All was normal.

That winter and spring were busy for John. He was ranking in the top twenty of his class—something that he was very proud of. Scott told me how John used to keep him up past two in the morning, doing his homework. “He would say to me, ‘Dad, I’m really tired tonight. Could you type my paper?’ ”

John spent a lot of time on his senior project about his cancer treatment. Scott recalled that John put all of his energy into it. “He wanted everything so perfect. There were nights he would type a page and ask me to retype it word for word, the way he had it. John would always change a word or two, but he would want to compare the two pages side by side to make sure it was perfect. John got all of his CT scan slides and used them for his presentation. I wasn’t in the room, but from what I was told it was pretty remarkable. He would point at the slides on the screen and show the tumor that was killing him. I talked to Robert Staub, his principal then, and he told me he had to walk out. ‘It was very emotional for me to watch this eighteen-year-old student talk about the cancer that was killing him—like it was nothing. The poise and dignity he showed was remarkable,’ he said. John told me he wanted his senior project to be one teachers would always remember. He must have been right, because I still hear about it today.”

On March 25, John had his routine chest and abdomen scans. Dr. Graves passed along the bad news: John’s cancer had grown in both his liver and lungs. He was very direct with John, Scott, and Gina when he told them that the growth “was not a good thing. The cancer is not going to go away.”

John asked him a lot of questions. “Why can’t we just cut some of my bad liver out and give it a chance to grow?”

Dr. Graves said that the reason John kept throwing up was that there was no space in his belly due to the cancer spreading. In the four weeks between scans, the cancer hadn’t doubled in size, but it had grown a lot, spreading to John’s pelvis.

Gina recalled the appointment: “[Dr. Graves] told John the cancer was winning. John asked him, ‘How long do I have?’ Dr. Graves told him that time was short. . . . I wanted to hug John, but I knew I still had to show John that I believed that there was still a lot of time left. I had to leave the room to schedule another appointment. John started to cry after I left.”

“This was the second time I saw the emotion really come out of John,” Scott said. The first time was the day he found out he had cancer. “Dr. Graves was sitting in front of him and was holding on to each side of John’s face so gently. Tears were running down John’s cheeks, and he turned to me and said, ‘I’m sorry, Dad. I’m letting down all those people who have been praying for me.’ That was John—more worried about everyone else than himself.”

At this time, twenty-two months after his diagnosis, John was slowing down little by little each day. Gina described how John needed to rest more and more. “As a family, we tried to keep things going and keep our family life as normal as possible, not only for John, but for Lexie too,” she said. “We went to work each day. Most of the time we ate together as a family. There was always a lot of tension. We tried to include Lexie in a lot of things, but we also tried to protect her so she didn’t see the hurt and sadness in us. She was now only fourteen.”

![]()