Garden party at Rogers Farm, 1915—raising funds for the Red Cross.

IMAGE 1978-003-002 SAANICH ARCHIVES

Whenever people live near each other in large numbers, especially if they are far from their original homes, sooner or later they will socialize. Over a hundred years ago in British Columbia, this was especially true among these already described upper-class families in Victoria.

That need to socialize, with luncheons, afternoon teas, balls, and dinner parties, extended to a need for entertainment. To begin with, however, certain standards of rank and position had to be firmly established. It was essential to define the boundaries so that social activity could be categorized and enjoyed within the individual classes.

F.E. Walden, in his Social History of Victoria, 1858–1871, wrote,

The British governing clique held firmly to its position as the upper class in Victoria. Governor Douglas and the succeeding governors, their wives and families, entertained the high supporting officials of the colony, most of whom were resident in Victoria. High-ranking officers of the Royal Navy and the Royal Engineers were included in this circle, and junior officers of the Services provided suitable escorts for the young ladies of these families. High officials of the Hudson’s Bay Company completed this ruling hierarchy.75

Everyone belonged to a particular class, and this was clearly understood and accepted by all. One’s class status dictated whether or not one was inside or outside that elusive circle described as the “ruling hierarchy.”

In the days of the fort, to be inside the circle meant you were in some way connected to the Hudson’s Bay Company or had come to the colony from a suitable middle- or upper-class background, and had a good education to boot.

Once one’s appropriate class (in this case upper) was established, one could merely sit back and enjoy all the social activities available. And there were many. A rather flowery account in the Colonist of August 1890 described Victoria high society’s quest for pleasure:

Society in Victoria gave itself away to pleasure early last evening, and continued its ardent worship till an equally early hour this morning. Society bent low and devoutly before that shrine, the god of pleasure, which it so deeply adores, and thought of naught else besides. The world was forgotten for the nonce, because a call was made which demanded immediate obedience. The call was responded to most eagerly and the place resorted to was the Assembly Hall.76

The event the Colonist was referring to was a ball given in 1890 for Rear-Admiral Hotham and the officers of the Pacific Squadron, but upper-class Victoria was no stranger to such elaborate occasions.

Two early writings offer a glimpse of some of Victoria’s worship of social activity in those years. The first comes from the pen of Robert Melrose, who arrived in the colony in 1853 to work as a carpenter for Kenneth McKenzie at Craigflower Farm. Strictly speaking, Melrose did not, by definition, qualify as a member of the upper-class circle, but his diary throws considerable light on how everyone, be they upper, middle, or lower class, lived and socialized at that time.

He frequently wrote about the amount of liquor consumed in Victoria, and his descriptions of Christmas and New Year’s celebrations: “fiddling, eating and drinking” and “celebrated in a glorious Bacchanalian manner”77 paint a vivid picture of the times. The only other occasions for socializing seem to have been funerals or weddings and, according to Melrose, there was certainly a plethora of both.

Martha Cheney Ella’s diary (1853–56) also gives an in-depth look at life in early Victoria. Martha arrived aboard the Tory in May 1851 with her aunt and uncle, Thomas and Anne Blinkhorn. Still in her teens, she wrote a lively account of their farming life in Metchosin on Vancouver Island. Her diary is the only known account of life in the pre-gold rush era from a woman’s point of view. Only parts of the diary have survived, written in a blue-lined scribbler; even those sections are hard to decipher.

It is especially interesting in its descriptions of Victoria’s social life. Martha, like many pioneer women of that period, worked hard all day, ironing, churning butter, and being generally occupied with farming chores, but she was able to “dance until 4 o’clock in the morning at the Governor’s Ball at the Fort.”78

Much of the socializing took place in the farmhouse itself, where guests often stayed overnight and were entertained with good conversation and equally good homemade meals. Martha makes frequent mention of “a houseful of company,” their farmhouse being a halfway point between the fort and Sooke.

The Royal Navy played a large role in the social life of those first colonists, like Martha Cheney and the Blinkhorns, just as it did with the Puget Sound Agricultural Company’s farming families, such as the Skinners, McKenzies, and Langfords. Frequent dinner parties or balls were held aboard the visiting naval vessels, and everyone who was anyone was invited.

This is corroborated by many other accounts, one in particular by Lieutenant Charles Wilson of the Royal Engineers in his journal. In August 1858, he wrote:

In the evening we all went to a ball given by the officers of the Plumper, where we met all the young ladies of Vancouver Island, they only number about 30 and are not very great beauties, however, I enjoyed myself very much, not having had a dance for such a time. Most of the young ladies are halfbreeds and have quite as many of the propensities of the savage as of the civilized being.79

In a later entry, Wilson wrote:

We are quite gay here now, nothing but Balls, private Theatricals etc., with the Flag ship and other ships there is quite a small fleet.80

• • •

It is apparent that socializing in early Victoria took place either at the initiation of the Royal Navy or within the compounds of the fort itself. There the company men enjoyed themselves royally in Bachelors’ Hall.

Captain Grant, Vancouver Island’s first settler and a frequent visitor to the fort, was a good example of one settler who managed to enjoy a good social life despite the hardships and isolation of his environment. He was by nature a sociable man who sought good companions along with good whisky, and his contributions to the fort’s social scene were considerable. One evening, he encouraged the younger company men to bound around Bachelors’ Hall like kangaroos, supposedly imitating Queen Victoria’s coach horses pulling her carriage around Windsor Park.

However, worthwhile pursuits did eventually arrive at Fort Victoria. They came in the form of cultural activities such as theatricals, a popular pastime enjoyed by many of the first colonists on Vancouver Island. The earliest recorded amateur theatrical performance given in Victoria was a production by the gentlemen of the fort in January 1857 of Sheridan’s play The Rivals. The cast was rather grandly referred to in the program as the “dramatis personae” and included such notables as Colonial Surveyor Joseph Pemberton playing the part of Sir Lucius O’Trigger, Chief Trader J.W. McKay in the role of Sir Anthony Absolute, and Pemberton’s assistant, Benjamin W. Pearse, as Fag.

The audience was also treated to an amusing prologue, which explained the play’s long delay in production as due to various “duties” in which the cast had been involved and that had kept them busy. In this connection, a joke was made about each member of the cast, describing their activities at that time. This no doubt held great significance for the company men and had the crowded mess-hall at the fort rocking with laughter far into the night.

The popularity of dramatic productions continued to increase. On occasion, touring companies from San Francisco also paid visits to Victoria. Victoria liked to laugh, so comedy was always in great demand. The standard of entertainment was not particularly high, and a visitor to the city once remarked that “taste for the noblest form of the drama is not general.”81

By 1860, the town had also been entertained to a production of Lucretia Borgia at the recently erected Colonial Theatre. Theatres at that time were being built at an almost alarming rate and seemed to go up virtually overnight.

In July 1862, under the patronage of Governor Douglas, a high-quality theatrical group of entertainers called the Dillon Troupe presented Othello, Delicate Ground, and Morning Call. It was their last performance in North America before leaving for Australia. Later productions in the city included The Jewess and Judith of Geneva.

Eventually, with fewer theatrical groups visiting Victoria, the citizens decided to form their own. They called it the Victoria Amateur Dramatic Group, and it was composed mostly of well-educated gentlemen (no well-bred lady would have been seen dead on the stage). Membership was five dollars. Their first performance was at the Victoria Theatre in December 1862 and included two plays, Bachelor of Arts and Little Toddlekins. Governor Douglas remained as patron.

James Douglas’s daughter, Martha, also enjoyed the theatre. She reports in her diary in 1867:

This evening Papa and I went to the theatre to see a performance by the Amateur Dramatic Association for the benefit of the Fire Company. Two pieces were acted: “Time Tries All” and “Retained for Defence” with a Musical Interlude. The acting was very good, especially Miss Jenny Arnot who is very much improved in manners and appearance since I last saw her.82

Unfortunately, the theatres were extremely cold and often uncomfortable even for upper-class patrons, and unless one owned one’s own carriage, it was difficult to travel to the theatre in time for the performance. As late as 1866, there were rarely more than six hacks available for hire.

The wealthy, however, continued to enjoy their theatrical pleasures for many years. In keeping with their simple and uncomplicated lifestyle, they also revelled in musical entertainment. Their evenings often consisted of organized musical socials in the fort or in their own homes.

The first piano to arrive on Vancouver Island came in the spring of 1855 and was the proud possession of Mrs. Mouat, wife of company man Captain W.A. Mouat. Augustus Pemberton had brought his flute from Ireland, Benjamin W. Pearse and the Reverend Cridge played violin and cello, respectively, and this completed the talented musical ensemble within the fort.

Strong interest in this type of musical soirée meant that it was not long before a philharmonic society was formed, to present more professional concerts on a regular basis. A group of musicians met in January 1859 at the home of Selim Franklin and elected officers for the newly formed society. Judge Matthew Begbie was elected president, and Franklin vice-president. The society gave regular performances, usually at the Assembly Hall on Broad Street, where they often performed to large audiences.

A cultural pursuit equally popular with the upper class was literature. Everyone loved to read, and soon the demand for books and periodicals far outweighed the supply. There appeared to be a desperate need in the early settlers not to be thought of as merely backwoods colonists. The upper class still considered themselves the intelligentsia, despite the isolation of their environment, and reading was one way to keep abreast of affairs. It was not long, therefore, before a need was seen for a library in Victoria.

Soon after the first influx of miners arrived in the spring of 1858, a Frenchman named W.F. Herre started the first library. It consisted of a reading room “in conjunction with a saloon,” but according to the Victoria Gazette, the library was “as yet limited, but so soon as books can be obtained from San Francisco, will be greatly enlarged.”83 At least it was a beginning.

When Herre departed for France, he put his businesses, including the library, up for sale for twelve hundred dollars. Nothing more happened for a year, and then a reading room was opened by the Young Men’s Christian Association. It was situated on Yates Street and later moved to the ground floor of Dr. Dickson’s house on Government Street. Hours were from five to ten o’clock every evening, and the charge for membership was six shillings. The reading room was mainly stocked with religious publications, scientific papers, and periodicals from Great Britain, and it provided a place where people of all classes could go.84

Soon a group of interested patrons went one step further and formed the Victoria Literary Institute. Membership was five dollars, with a monthly subscription of one dollar paid by the board of directors in addition. A librarian and staff were appointed. During 1861 and 1862, a series of lectures and readings were held. They were all well attended by the town’s leading and most influential people; the church, the government, the HBC, and the town’s community of merchants were all represented.

Funds were raised for future readings but, although the idea had initially seemed to be popular, the Literary Institute eventually met its demise. It had, however, served a purpose in that it had brought together upper-class citizens for the benefit of good literature and stimulating company. It also set a certain standard and was a foundation from which to work.

A similar organization, which had long been popular in England, was the Mechanics’ Institute. Its purpose was to “supply technical instruction to artisans . . . [and had] . . . developed into a social institution including book collections.”85 A Victoria branch of this institute opened to the public in 1864. It operated from two rooms on Langley Street and soon included a library, where cultural and scientific lectures, readings, elocution classes, and a debating club were held.86

The institute also sponsored such pleasurable pursuits as picnics, theatricals, and boat excursions, and organized a chess club. Picnics, in particular, had always been a favourite pastime for the settlers. An early picnic presided over by Amelia Douglas herself was described delightfully:

My first experience of a real picnic was on the occasion of one given by Mrs. Douglas to the school children at the North Dairy Farm. Dump carts, wagons and any other rough vehicles and horses were put into requisition for the conveyance of the guests on this memorable occasion. Can I ever forget the lurid happiness of that delightful day? In my boyish imagination I could not conceive anything grander, more luxurious or extravagant could be done in this world. The glorious day, the unrivalled scenery, at that time unspoilt by the hand of man, the wealth of floral beauty, the thorough enjoyment of the drive in the rough vehicles, the rich milk and cream from the dairy, the jam tarts with twisted ropes of crust over them, the cookies and unlimited bread and butter, were to my mind the acme of extravagant luxury, and lastly, the drive home in the evening concluded this never-to-be-forgotten day of happiness.87

Picnics continued to be fashionable in Victoria for many years. Later, those held on the lawns of Point Ellice House were among the most enjoyable, and certainly the ones at which to be seen.

Navy or military personnel also organized picnics, such as the one held on Saturday, August 1, 1885, at the Agricultural Grounds at Beacon Hill. Under the patronage of the lieutenant-governor, the picnic was billed as an “Artillery Picnic” and was held by the officers, non-commissioned officers, and men of the BC Garrison Artillery. It too was well attended.

Through the years, more elaborate amusements were added to the simple lifestyle of the original colonists. Soon there were cricket matches or the ever-popular horse races at Beacon Hill, croquet and tennis tournaments on the lawns of the most elite homes, elaborate celebrations of the Queen’s Birthday in May each year, and the annual regattas along the Gorge. It was indeed a time when Victorian high society gave itself up fully to the important business of pleasurable pursuits.

In 1861, the Jockey Club was formed for the promotion of horse racing on Vancouver Island; the fee was twenty dollars. Two meetings were held annually, one in spring to coincide with the May 24 celebrations, and the other in the fall. Naval and military personnel were admitted to club membership, with the Honourable H.D. Lascelles of the Royal Navy being one of the most prominent riders for the club. Original membership indicates “a predominance of Englishmen of the official governing class, and the officers of the navy and army, with lawyers and judges admitted.”88

The tradesman and first mayor of Victoria, Thomas Harris, was an exception to this membership rule, probably because of his obvious knowledge of and experience with horses, and his great organizational skills. Being merely a merchant and certainly lacking in education, he would not have qualified as a member of the establishment.

Elaborate regattas organized by the Royal Navy usually took place in Esquimalt Harbour or along the arm of the Gorge. Whalers and cutters were pulled by crews over a designated course, and the races were watched by spectators from aboard launches and barges. Large crowds would also gather along the banks of the Gorge. A regatta was one of the few occasions when class distinction was often forgotten in the excitement of the moment.

One of the most spectacular regattas ever held was during Sir John A. Macdonald’s visit to Victoria in 1886. On that hot August night, the waters of the Gorge were ablaze with the lights of hundreds of Chinese lanterns and torches. Over a thousand people gathered around the Point Ellice Bridge to witness the approaching flotilla making up the regatta. Next day, the Colonist described the procession:

At Point Ellice hundreds of torches were blazing, making the darkness light, and the many lights rose gracefully and picturesquely into the air. Out of the darkness came the grand water pageant, moving along slowly, resembling a ship burning at sea, or a mountain flickering with the myriad lights of a host of fireflies.89

The Queen’s birthday every May 24 was an equally important social event for Victorians, particularly those of British background. Toasts were drunk to Her Majesty’s health throughout the day, while dances were held by the elite.

Most of early Victoria’s upper class liked to travel abroad. Visits back to the old country and tours through Europe or the United States were the rule rather than the exception. But one excursion that took place nearer Victoria in 1879 was somewhat different and, at the time, drew considerable attention from the press.

In the Colonist of August 13 that year, a report announced that

the commodious steamer Princess Louise will leave the Hudson’s Bay wharf this morning on what promises to be a very pleasurable trip completely around Vancouver Island—a great adventure.90

It would indeed prove to be a great adventure and, as usual, when something innovative was about to happen, many of the town’s most important citizens were involved. For this excursion, such notables as Justice and Mrs. Crease, Captain and Mrs. Vidler, the photographers Richard and Hannah Maynard, BC’s first provincial secretary and an early mayor of Victoria, Alexander Rocke Robertson, the fiery politician Amor de Cosmos, another mayor Charles Redfern, and clothier William Wilson, were all aboard.

Charles Kent and his son Herbert, both well known in musical circles in Victoria for many years, were also among the passengers on that notable trip. When the party returned ten days later, the younger Kent wrote a detailed account of the adventure for the Colonist. His vividly descriptive article ended:

Thus was completed a most enjoyable excursion. All those who were on board speak very highly of the appointments of the splendid steamer, and the courteous manner in which Capt. Lewis and his officers exerted themselves to ensure safety and comfort.91

It may have been only a boat ride around Vancouver Island, but to Victorians it was a memorable event of great importance.

• • •

It is safe to say that the elite certainly knew how to amuse themselves, but it was at their balls and banquets where they really excelled.

In the early days, all the most important balls were held aboard visiting naval vessels or in the Douglas family home on Elliot Street, which doubled as Government House. The Assembly Hall on Fort Street near Vancouver Street was also an important location for the elite to gather and dance the night away, as was Armadale, home of the MacDonald family, and Cary Castle, which later became the official Government House.

One of the most fashionable and impressive balls held in Victoria was given by Governor Kennedy in May 1866. He had purchased Cary Castle as his official residence the year before and was now eager to impress everyone with the opulence and grandeur of his station. Hundreds of invitations were sent out, not only to high society in the colony of Vancouver Island, but also to the English and American garrisons at San Juan Island. Guests were received in the drawing room by Governor and Mrs. Kennedy and their two pretty daughters. A visitor from California, referred to simply as Miss Banks, also made up the reception line.

At 9:00 PM guests were ushered into the ballroom and the first quadrille began. Between midnight and 1:00 AM, the supper room was opened up although “dancing was maintained” during the interval. Later, the governor proposed the health of the queen, and Mayor Lumley Franklin proposed the health of the governor.

“On repairing to the ballroom,” wrote the Colonist next day, “Miss Kennedy ably presided at the piano, while the musicians partook of refreshments.”92 Dancing continued until 3:00 AM at which time the two Miss Kennedys sang the first verse of the national anthem. Mayor Franklin contributed the second verse, followed by Miss Banks with the third. The Colonist added that “the audience were completely electrified by the magnificent and highly cultivated voice possessed by this gifted young lady.”93

The ball was considered a resounding success.

Another such event was held in November 1871, to celebrate the thirtieth birthday of the Prince of Wales, who later became King Edward VII. Lieutenant-Governor Joseph Trutch and his wife were the hosts at Cary Castle on that auspicious occasion, the first of many during Sir Joseph’s time in office.

The following May, Government House was again the scene of a pleasant social gathering, this time a ball to mark the Queen’s birthday. The Trutches sent out four hundred invitations, and the rooms were crowded to capacity with elegantly dressed ladies and gentlemen.

The Assembly Hall was the site of the spectacular ball in August 1890, given in acknowledgment of the many courtesies received by the colonists from naval representatives. This ball was

an attempt at making the representatives of Britain’s maritime power feel that, though they sojourned among colonists, their lot had fallen among British subjects, whose ambition for Britain’s welfare is the same as theirs, whose hope is that they may ever continue to be one of England’s most substantial bulwarks, as well as her chief colony.94

On such occasions, the Assembly Hall underwent a “marvelous transformation” wrote the Colonist. It became

a fairyland in miniature, peopled by beings who, though manifestly material, seemed happy, every bit as ethereal beings, as they walked hither and thither with that gait and manner which, in their apparent abandon, speak of minds free from present care, past trouble, or future anxiety. Smiling faces, laughing voices, handsome uniforms, rich flowers, bright and flowing, modest flowers, shrinking and shy, vigorous flowers, braving the heat and artificial lights as naturally as though it were the place wherein they bloomed first, multi-colored flags of nations as numerous as the colors they contained.95

The account continued in the same sugary mixture of Victoriana, intended no doubt to titivate and stimulate the reader. Perhaps the most delightful snippet from the overly exaggerated account is the mention of the conservatory beyond the ballroom itself. It was there, stated the Colonist, that a “tête-à-tête could be had away from the dreamy dance, or a dance would be, as it so often is, ‘talked over.’”96 To eavesdrop on some of those conservatory conversations would have been most enlightening.

It was, however, at the many masked balls that Victoria’s high society really outdid itself. At one such event held at the Crease home, Pentrelew, Augustus and Jane Pemberton’s son Chartres dressed as Christopher Columbus, his cousin Fred Pemberton as an outlaw, and a third cousin visiting from England (with the delightful name of Perfect) was outfitted as an Italian peasant.

The masquerade ball in 1899 in aid of the Royal Jubilee Hospital was probably the event of the century for high society in Victoria. It certainly had everyone talking for weeks in advance, and no doubt while costumes were being decided upon and made by the seamstresses, books such as Weldon’s Practical Fancy Dress for Ladies and Gentlemen were referred to.

Again the ball was to take place at Assembly Hall, and headlines in the Colonist the following day read, “Masks and Merriment sweet pleasure was Queen—brilliance unsurpassed—entertainment enchanting.”

All the most important people in Victoria were present, although one would have been hard pressed to recognize any of them. The Pemberton family was well represented and magnificently attired. Mr. and Mrs. Fred Pemberton were dressed as a Viking and The Lady of Seville. Other family members were garbed as Madame de Pompadour, Chaseur d’Amérique, and in a costume from the First Empire (in white and silver).

Miss Maude Dunsmuir was dressed in pale blue gauze as Desdemona and Miss Birdie Dunsmuir as Cigarette from Ouida’s Romance. Noel Harvey, a Dunsmuir granddaughter, came as a pink carnation.

Mrs. Harry Dallas Helmcken arrived as a court lady of the early empire, and Mrs. Dennis Harris (James Douglas’s youngest daughter) was dressed in “magnificent brocade, becoming her statuesque beauty well.” Mr. and Mrs. Harry Barnard were present, she attired in a peasant costume from the province of Vladivostock. Mrs. Herbert Kent was dressed as a yacht girl, Reginald Hayward as a Heidelberg student and his sister Florence as Economy. Even the famous architect, Samuel Maclure, and his wife were present, she dressed “in a splendid characterization of the Old Lady, wrinkles, eyeglasses and ear trumpet not forgotten.”97 The upper-class socialites were nothing if not imaginative.

They also liked to eat. Their dinner parties and banquets were perfect examples of the enormous amount of food they consumed. For instance, to mark the occasion of the Victoria Board of Trade obtaining its own building on Bastion Square in May 1893, an elaborate ten-course banquet was held and continued far into the early hours of the next morning. Among the illustrious guests enjoying the plentiful fare were Premier Theodore Davie, Robert Beaven (leader of the Opposition), Lieutenant-Governor Edgar Dewdney, financier A.C. Flumerfelt, Chief Justice Sir Matthew Begbie, industrialist Jacob Hunter Todd, and business tycoons David Ker and Robert Rithet. When the company finally rose to sing “God Save the Queen” at 4:00 AM, many of them could barely stand.

Dinner parties were held on a regular basis in the homes of the elite. The O’Reilly family, in particular, entertained on a large scale and retained all their dinner menus. They ate a great deal of lamb, roast fowl, and curried lobster, and their favourite desserts were “puddings”—marmalade, gingerbread, or jam roll being top priorities.

A list of the retail grocery prices in January 1892 shows that three assorted jams could be purchased for one dollar; lemons from Sicily cost fifty cents each whereas from California they could be had for thirty-five cents. Reindeer milk (in tins) cost twenty-five cents and a fresh tin of oysters went for seventy-five cents. Fresh eggs were fifty cents a dozen.98

One of the most enlightening glimpses into how and what Victoria’s upper-class citizens ate comes from the Barnard Family Collection. Lady Barnard kept a dinner party record book at the turn of the century, describing in detail the parties held both at Clovelly and at Government House during her husband’s sojourn there as lieutenant-governor.

Her record book is delightfully inscribed at the beginning with a quotation from Byron:

That all-softening, over powering knell, The tocsin of the soul—the dinner bell.99

Indeed, if the record book is to be believed, the dinner bell must have sounded on a multitude of occasions. Each dinner party is described in detail with the date, the occasion, the guests present, the seating arrangements, and the menu itself. A particular added delight is a notation concerning “particulars of table decoration.” If, for instance, it was springtime, primroses and daffodils were in profusion on the table. Yellow roses were featured in summer, carnations and chrysanthemums in fall. At Christmas, holly was always in abundance as a centrepiece.

At Clovelly, the guests frequently enjoyed caviar followed by a consommé or cream soup, sautéed chicken, roast lamb, and asparagus. Dessert would often be rhubarb tart or chocolate pudding followed by cheese straws and ice cream. Other favourites were boiled salmon and roast duckling, and oysters on the half shell were frequently included.

At Government House, Lady Barnard continued to enjoy her dinner parties and always made a special point of decorating her table to suit the occasion or the visiting dignitaries. In April 1915, when the Japanese high commissioner visited Victoria, her table was set with Japanese cherry blossoms.

Between 1916 and 1919, the Barnards also entertained many royal personages, including the Duke and Duchess of Connaught, Princess Patricia, the Duke of Devonshire, HRH Prince Arthur, and HRH the Prince of Wales. For all the royal visits to Government House, she meticulously kept account of the dinner parties, noting on her table plan where everyone was to be seated. She even mentioned those guests unable to attend. That column was rarely filled, however, because an invitation to a Barnard dinner party was something one did not decline.

• • •

Many of the upper-class ladies of early Victoria were often thought to be idle, contained as they were in their luxurious lifestyles. A rather snobbish attitude to their servants or those of an inferior station, and the fact that they seemed to be concerned only with trivial matters such as their at-homes or their afternoon teas, tended to give the impression of laziness,

In many ways, however, it was a frustrating time for women, and even those who wished to occupy their days with other things were limited to activities such as gardening, painting, music, or helping charitable organizations. Those were thought to be the only occupations in which ladies should be involved.

The Alexandra Club, which officially came into existence on August 17, 1900, served many purposes, not the least of which was to occupy those upper-class women in more worthwhile pursuits. The club interested itself in music, literature, and the arts by introducing and sponsoring young artists and bringing them to the attention of the public.

A proclamation issued that August stated:

We the undersigned hereby agree to form ourselves into a club for the use of the ladies, to be called The Ladies’ Club under the direction of a committee to be elected by a majority of the subscribers hereto. That we agree to pay an entrance fee of five dollars with a month’s subscription of one dollar payable quarterly in advance. It is further understood that as soon as fifty intending members have subscribed to this paper, a meeting will be called of the same with the object of electing a committee . . . for carrying out our desired purposes.100

With those words, the first women’s club in Victoria came into being. There were already fifty-six signed-up members, all anxious to be a part of the organization. Numbered among them were three Dunsmuir women, Mrs. Harry Barnard, Mrs. Powell, Mrs. Pemberton, Mrs. Dennis Harris, Mrs. Dewdney, and Mrs. Prior. The majority of Victoria’s most fashionable families were represented at the club by their women.

Although first and foremost a social club, it also served in other capacities, doing much useful work. The Ladies’ Club later changed its name to the Alexandra Club to honour Queen Alexandra, wife of the then-reigning monarch, Edward VII.

The first clubrooms were in a building at the corner of Fort and Government streets, directly above Charles Redfern’s jewellery and silver store. A steep, winding staircase led up to the quiet, dignified atmosphere of the club, where ladies could sit and read, take afternoon tea, watch the world go by from the windows, or discuss, in hushed tones, the charitable projects in which they were involved. At last, being part of an organization such as the Alexandra Club, they felt needed and somewhat important. In particular, they enjoyed the feeling of belonging to a club where they could go and discuss matters of significance.

It was soon decided to build a more prestigious clubhouse, an idea initiated by Mrs. Hazell, wife of Dr. Hazell of the Royal Jubilee Hospital. Mrs. James Dunsmuir advanced the money, and construction of the Alexandra Clubhouse began immediately.

The new clubhouse stood at 716 Courtney Street and was later known as the Windermere Building. It was furnished with the very finest of everything; meals were served on elegant china, and the silverware was polished and sparkling.

The first fundraising function of the club was, naturally enough, a ball. The clubhouse was decorated for the event with a profusion of flowers, and the ladies, wearing their most beautiful gowns, arrived with their escorts. The event was the first of many.

Balls, literary events, receptions, musical evenings, and weddings were just a few of the occasions in which the Alexandra Club involved itself. A particularly memorable event was a reception given by way of farewell for Lady Goodrich, wife of the admiral at Esquimalt. The Royal Navy was making its departure from the west coast, and Canada was about to take care of its own defences. The Alexandra Club wanted to mark the occasion with a happy reminder of Victoria’s association with navy personnel.

For many years, club members continued to enjoy the elegance of the environment they had created. It was a graceful era, hard to imagine in today’s world. Scattered on occasional tables, amidst the potted palms in that ethereal atmosphere, were copies of many old-country magazines such as Ladies’ Field or the Illustrated London News. Described in the newspapers of the day as a club housed in one of the finest buildings in Victoria, the Alexandra Club appealed to all the most influential women.

As in all things, however, times change, and even prosperity and elegance eventually disappeared in the general cycle of life. As war clouds began to appear in 1914, it became obvious that this was no longer a time for frivolous pursuit and reckless spending, even though many of the club’s functions had been fundraisers. Now the ladies of Victoria turned their attentions to more serious endeavours. Some members joined the Red Cross or the Victorian Order of Nurses, and many organized fundraising events to further the patriotic cause.

Garden party at Rogers Farm, 1915—raising funds for the Red Cross.

IMAGE 1978-003-002 SAANICH ARCHIVES

The club’s expenses continued, but money was no longer available. Soon it was necessary to sell the clubhouse on Courtney and move to a smaller location at the top of the Campbell Building. Here there was less space, but the ladies continued to carry on their club activities, albeit on a smaller scale. On one occasion they invited Mrs. Pankhurst to be a guest speaker. Later the club was forced to move yet again, this time to the Bank of Toronto Building. But the end was near. By this time, the Union Club of Victoria, that inner sanctum of masculine pomposity, was finally beginning to open its doors to its members’ wives, many of whom were also Alexandra Club members. So, despite the demise of the Alexandra Club one year after its last move, the ladies still had somewhere to gather and discuss the events of the day. The Alexandra Club had served its purpose by successfully filling a very necessary spot in a world of grace that no longer existed. As late as the 1950s, some of the elegant Alexandra Club china, engraved with the club’s initials, was still being used at functions in Victoria.

Another early Victoria club, of a different genre, was the Arion Club. Launched at the initiation of thirteen gentlemen in February 1893, its purpose was “the study of music for male voices and also for the culture and development of a refined musical taste in its members.”101 The members performed their first formal concert on May 11 of that year in the Institute Hall on View Street. The concert was attended by ladies and gentlemen of Victoria, who all came formally dressed to witness the many talents of “the young gentlemen.” By the time of that May concert, membership had reached twenty-four and included such important names as George Jay (known for his work on the Victoria School Board and after whom George Jay School is named), Herbert Kent (who was destined to sing with the Arions for sixty years and become the club’s historian), James S. Floyd (Oak Bay’s one-time municipal clerk and a director of the Christ Church Cathedral Choir), and Ernest Wolff, local violinist, whose niece, Alma Clarke, became notorious as Francis Rattenbury’s second wife and the lover of a nineteen-year-old chauffeur who murdered Rattenbury in a fit of passion.

They were a colourful and very talented group of men, and their frequent concerts through the years were always well received by members, associates, and later the general public. Associate membership extended to many of Victoria’s social set, including Sir Matthew Begbie, Canon Beanlands, Henry Crease, and Mrs. Dennis Harris. By the 1936/37 season, associate membership also included Lady Barnard, Mrs. James Dunsmuir, Sir Richard and Lady McBride, and the Honourable T.D. Pattullo. Even ladies were permitted to sing with the male choir on occasion, but in the concert programs they were usually billed as “female guest artists” or “young lady amateurs.”

On May 14, 1993, yet another Arion concert marked the completion of a hundred years of singing by a unique musical organization that had survived a depression, two world wars, and at least sixteen different conductors102—a truly remarkable achievement and a proud relic of that world of social elegance in long-ago Victoria.

If one cares to ponder social activities from that other era, there is one more delightfully coy and tantalizing source, typically Victorian in content. It was known as the Victoria Home Journal, a gossip newspaper published in Victoria during the 1890s, intended above all else to tease and tantalize. By its own admission, it was totally “devoted to social, political, literary, musical, and dramatic gossip.”103

There was a column, “Society,” that told of the goings-on of the upper-class set. Its charm lay in the fact that it merely hinted, in a mysteriously intriguing manner, at what was taking place around the city. It never stated complete facts, and many of its reports began with the words “rumour has it.” Names were never mentioned, and the leading players in each story were described in cleverly disguised ways.

“A well-known Victorian, prominent in yachting circles will shortly wed the leading soprano singer of St. Andrew’s Cathedral choir,” read one report. Others stated that “the marriage of a well-known druggist to a fair young lady of this city is announced to take place in June”; “There will be a fashionable wedding at Christ Church Cathedral soon. Both of the high contracting parties are popular in society circles”; “The wedding of a prominent young barrister to an equally prominent society belle will be the matrimonial event of next week.” Less flattering reports were also written on occasion. In its day, the Victoria Home Journal was probably the equivalent of the most shocking tabloid stories a hundred years later. The Journal also had a column titled “Of Interest to Women,” consisting of enlightening words of encouragement for women who might need advice on otherwise unmentionable subjects such as marital or health problems.

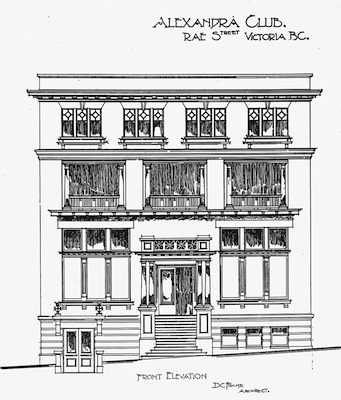

Architect’s drawing of proposed new clubhouse for Ladies’ Club on Courtenay Street.

VCA 98410-10-643

Cast of a Grecian play-theatrical at the Pemberton estate, Gonzales (date unknown).

VCA 98202-25-4576

Typically large upper-class wedding party—Jessie Dunsmuir/Richard Musgrave wedding showing six bridesmaids, two flower girls, and twenty matrons of honour in attendance. September 1891.

IMAGE D-03604 COURTESY OF ROYAL BC MUSEUM, BC ARCHIVES

Major social event of 1878 — marriage of Martha Douglas (daughter of Sir James Douglas) to Dennis Harris.

IMAGE A-01236 COURTESY OF ROYAL BC MUSEUM, BC ARCHIVES

Wedding of Canon Arthur John Beanlands to Sophie Pemberton.

IMAGE 1-46770 COURTESY OF ROYAL BC MUSEUM, BC ARCHIVES

The Journal could be purchased for a yearly subscription of one dollar and found its way into many a home in Victoria in the Gay Nineties. Perhaps its most important contribution was the fact that it endeavoured to keep the ladies and gentlemen of Victoria up to date on fashion. The “Clothes” column was an invaluable source of information for them and was read religiously by those who wanted to keep abreast of the times.

The way the upper class dressed had, after all, always been of paramount importance, ever since the days of the fort. The fact that these settlers had chosen to live many thousands of miles away from world fashion centres like Paris or London did not deter them from making sure they always dressed in the most current fashions and appeared presentable, as befitted their station in life, on every occasion.

Tea in the garden at Helmcken House, 638 Elliott Street (c. 1900).

IMAGE 1981-019-029 SAANICH ARCHIVES