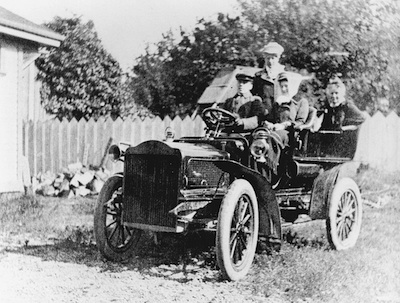

Mr. and Mrs. H.D. Helmcken, and D.D. McTavish on the left, with the Helmckens’ Pierce Arrow automobile, 1907.

IMAGE 1981-019-052 SAANICH ARCHIVES

Appearance! To most of the upper social set in early Victoria, it was of the utmost importance. How one appeared in public or how one presented oneself to the outside world was the driving force behind most of their social activity.

With so many formal occasions to attend from the days of the fort on, there was never a time when it was not essential to be well turned out. Ladies did not want to be thought of as mere backwoods women, and gentlemen most certainly wanted their womenfolk to be not only presentable but perhaps a little above average. Judging by the flowery descriptions of ladies’ gowns in the newspapers of the day, especially for weddings, the situation from the very beginning took on almost a competitive element.

Isaac Singer had patented the first sewing machine around 1851, and these new-fangled machines were finding their way to far-flung places like Victoria, which helped the fashion situation enormously. In addition, by 1863 Ebenezer Butterick had perfected the paper pattern. The first one, made of stiff paper, was put on the market that year and was a great success. By the following year, Butterick and his wife were making patterns for children’s clothes from tissue paper. Salesmen were reporting a great demand for women’s clothes, and soon the Buttericks were mass-producing their patterns to meet this demand. By 1869 they had founded a fashion magazine, later called The Delineator.

The sewing machine and the paper pattern were two very progressive steps in the dressmaking industry and meant that, by the 1870s, with the help of their seamstresses, the ladies of Victoria were able to increase their wardrobes speedily. It was now possible to have clothes made in the city, instead of having to travel abroad to buy in quantity, or send to London and Paris for gowns once the latest collections were released.

For the first twenty years of Victoria’s existence, most ladies suffered the indignities of the crinoline for both day and evening wear. The crinoline skirt was anything but practical. It was cumbersome and awkward, with four narrow steel hoops running through the petticoats. Some ladies discarded the hoops but insisted on wearing stiff muslin petticoats to create the same effect. Either way, they often carried around with them at least sixteen yards of heavy, bulky material that was virtually impossible to organize into a comfortable sitting position.

The Douglas girls did not cope well with their crinolines, as can be seen from a journal entry made by one of the British officers at the time:

They [the governor’s daughters] had just had some hoops sent out to them and it was most amusing to see their attempts to appear at ease in their new costume.104

It was hardly surprising that by the early 1870s, the crinoline had all but disappeared in favour of a straighter style of skirt, but the change caused many ladies to feel vastly underdressed. They now had a mere ten yards of material in their gowns.

However, that early fullness in the skirt had simply changed position. The new fashion was called the bustle, placed at the rear of the skirt in the area where one would normally have sat. The bustle was worn high or low depending on the social standing of the lady’s husband. It was created with the aid of wires or steel and was often so heavy that it required the support of a harness from the shoulders. It was not until well into the 1880s that fashion designers began to see the wisdom of a more simple line in women’s apparel.

When common sense finally prevailed, many women in Victoria must have breathed a sigh of relief After years of struggling with constrictive undergarments, hooped skirts requiring yards of expensive material that could be ruined by one misguided step on a mud-soaked city street, and uncomfortable areas in the rear of their gowns virtually restricting any ability to bend, women could at last enjoy a far more comfortable line. Ankle-length skirts and shirt blouses came about mainly as a result of women’s eventual participation in sporting events. And a move toward a looser Grecian line for evening wear made social life far more pleasant for the Victorian lady of the 1880s.

Couturiers were soon establishing themselves around the world. Names such as Paquin, Doucet and Callot Soeurs became famous. One of the best-known men’s tailors in London, the House of Creed, opened a shop in Paris in 1854 and then progressed from men’s clothes to riding outfits for the Empress Eugénie and ultimately to beautifully tailored suits for women.

The Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876 offered Americans their first opportunity to see the French fashions. Custom dressmakers with a wealthy clientele regularly travelled from North America to Europe in order to bring back the very latest in fashion and then copy it for their clients, using the best of French fabrics. Sometimes the seamstresses who visited Victoria’s upper-class ladies in the spring and fall each year used their creativity by taking an original skirt from one design, a sleeve from another, and a neckline from a third, and incorporating them all into a unique gown that they quite accurately labelled “one of a kind.”

The introduction and brief popularity of bloomers was another innovation brought about by women’s interest in sporting activities. Many of Victoria’s ladies who took up bicycling at the turn of the century, for instance, enjoyed wearing them.

When an 1893 edition of Vogue magazine showed a woman dressed in a shooting outfit with her skirt reaching only to her calves, it might have been considered a move in a new direction. The lady was, however, wearing high boots to cover what would otherwise have been an area of exposed leg. Nevertheless, it was a statement by women who longed for a freer, more practical fashion.

Meanwhile, Charles Dana Gibson began making sketches of what he dubbed his Gibson Girl style, a definite American look, showing athletic young women dressed in shirtwaist outfits, boyish collars, puffed sleeves, and flaring, stiffened skirts. Sometimes he included a straw sailor hat. The Gibson Girl look was the beginning of ready-to-wear clothing in the American textile industry.

Yet another important event occurred in 1884. A French scientist, Count Hilaire de Chardonnet, developed rayon, the first of the man-made fibres. An artificial silk, rayon (its trade name) was made from the cellulose of pine, hemlock, and spruce trees.

The first few years of the twentieth century leading up to the First World War were carefree times in most parts of the world. There were no wars or depressions going on, so the rich were able to enjoy a constant round of pleasurable pursuits without fear of reprisal, and fashion trends tended to reflect this halcyon mood.

In Victoria, ladies continued the tradition of calling on their friends, arriving in their splendid carriages and, later, in their equally flamboyant motor cars. The clothes they chose for such pursuits were made of adaptable broadcloth and lace. For driving in those first automobiles, many ladies chose a linen duster outfit, which also served as protection from the dusty roads, and a bonnet tied with ribbon under the chin, which preserved many an elegant coiffure. For receiving at home, taffeta was a popular fabric choice. Fashion was greatly influenced, then as now, by famous personalities seen on stage or by other important members of high society, and trends still largely revolved around what was happening in Paris.

The new century brought with it small waists, puffed sleeves, and merry widow hats trimmed with ostrich feathers to create and enhance a lady’s appearance in a supposedly romanticized way. By 1908, with skirts now at ankle length, there was also a brief revival of the once-popular Empire line.

Between 1910 and 1914, many women followed the latest fashion trend and hobbled about in long, narrow skirts. Eventually, by the beginning of the First World War, skirts had once again become fuller and even shorter.

Three fashion houses had revolutionized the industry during those years. The first was Jeanne Lanvin, a couturière who opened her own establishment in 1890 and created, with her own hands and scissors, all her designs. Poiret began in 1910 and soon became known for his bold and exciting colours on Oriental backgrounds, his numerous trimmings, and his use of lamé (a fabric woven with metal thread) for evening wear. He also campaigned against the use of the corset and encouraged women to abandon all their most restrictive and uncomfortable undergarments. His new, looser line led to what eventually became known as the “debutante slouch.” A third great influence in the fashion industry was Madeleine Vionnet, who opened her house in 1912 and was the first to introduce the bias cut. This emphasized the line and cut of the garment, rather than its trimming, a concept that has survived.

And back in Victoria, how were the ladies in those important aristocratic circles keeping up with the latest fashions? When not poring over The Delineator, Vogue, or the ever-popular Weldon’s Practical Fancy Dress for Ladies and Gentlemen, they were, during the 1890s, avidly reading the Victoria Home Journal. By so doing they could easily find out the very latest thing happening in the fashion world.

There they discovered, for instance, that silk Roman sashes were all the rage. The sashes came in all tints of the rainbow, often with a deep silk fringe, and made a graceful drapery for an overly plain evening gown. Trimmings, especially feathers, were highly thought of. Clever rosebud creations were made with pink ostrich feathers and became exquisite decoration for any evening gown in pink or pale grey. The Grecian robe-style gown was worn often with its silken petticoats made of Amour, a new fabric that was thicker but softer than taffeta.

The latest Paris Opera coats arrived in Victoria during those years. They were made of cloth, with tan being the most popular colour choice. If a lady preferred to wear a cape, it was often an elaborate garment, graduated in length and trimmed with mink. A high Medici collar also edged with mink set off the cape, which was invariably lined with silk in a pastel colour. Around that same time period, wrappers were also very popular. These were dainty, airy, creations worn over a night robe, often made in accordion-pleated India silk.

Another theme in day or evening wear was to enhance a gown with tiny bows on sleeves or around hemlines. Pink crepe de Chine was favoured for evening gowns, while cloth day dresses still boasted the ever-popular leg o’ mutton sleeves.

Mourning wear was mostly made of black crepe, which had a dull crinkled effect. For half-mourning, black satin or large black and white plaids were acceptable. And a true lady was rarely seen in public without a hat, no matter what the occasion.

Fashion for men, on the other hand, changed very little through the years save for a few minor exceptions. Gentlemen in the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s wore elegant top hats and black overcoats with velvet collars for most occasions. Queen Victoria’s consort, Prince Albert, gave his name to the famous double-breasted frock coat that was popular for many years. Waistcoats and stiff collars were always worn, even for the most casual events.

Children were invariably dressed as elaborately as their parents, with little thought for the possibility of playtime or getting dirty. Little girls were outfitted in party dresses of silk and satin with numerous bows, ribbons, ruffles, and pleats. Small boys wore their Eton-collared Norfolk jackets, and knickers made of tweed.

Thus, even in Victoria, high-society fashion from the 1850s onwards was elaborate, formally stiff, and largely dictated by Paris trends. Perhaps the most overpowering influence through those years was an Englishman, Charles Frederick Worth, the man who can be credited with having begun the whole adventure into the world of haute couture. Worth originally came from London in 1846 to join a Parisian silk house and later established his own enterprise in that city. He was the first designer to show his creations on live models and the first who dared to dictate to his customers what they should or should not be wearing.

He was appointed court dressmaker to the Empress Eugénie in 1860 and was said to have been the main instigator of the famous hoopskirt crinoline. It is believed that he created it to camouflage the fact that the empress was expecting an heir. His wide-skirted, off-the-shoulder lace creations, known as Winterhalter gowns, were frequently worn as wedding dresses, and his lace flounces were particularly popular following the Empress Eugénie’s appearance in a ball gown that was said to contain at least a hundred and thirteen of them.

Every bride in Victoria who could afford it had her trousseau made by the House of Worth, and others also ordered their day and evening gowns; to be attired in a Worth creation was a status symbol. There were many daughters in the first families of Victoria at that time, so naturally there were also many weddings. This, of course, meant that a large number of very elaborate dresses for brides and bridesmaids were constantly being made, and descriptions of some of these dresses found their way into the newspapers. Today, family collections in the British Columbia Archives also hold detailed descriptions of some of the wedding outfits of the times.

When Jane Brew married Augustus Pemberton in 1861, for instance, her two flower girls were Martha Douglas and Amy Helmcken, and later Martha recalled and clearly described their outfits. They were made of white silk with matching white silk stockings, white kid slippers and white kid gloves. Their white bonnets had broad satin ribbons tied under the chin and pretty little wreaths of clematis around the face.

Some years later, in March 1878, Martha married Dennis Harris. Her father had already died, so she was escorted to the Reformed Episcopal Church by her brother, James. Her own gown was of rich white satin, trimmed with white tulle and orange blossoms. Her white tulle veil fell in graceful folds around her face and was held in place by a wreath of orange blossom. Martha had ten bridesmaids, each dressed in white tarlatan (a stiff, woven gauze) with ivy trimmings. They all wore wreaths of orange blossom. Three groomsmen completed the wedding party.

One of the largest weddings was that of Jessie Dunsmuir to Sir Richard Musgrave. Jessie’s gown was made of white and silver brocade with a full court train decorated in silver in the pattern of the Prince of Wales crest. Her veil and trimmings were of Honiton lace. Six bridesmaids wore dresses of white Charlotte Corday fabric, with long sashes and flowers to match. There were also two train bearers, two flower girls, and another twenty young ladies acting as maids of honour, an impressively large group rarely matched by society weddings at that time.

Thomas Skinner’s granddaughter, Emily Sophie (daughter of Constance and Alexander Davie), wore a gown of cream brocade trimmed with tulle and pearl embroidery for her wedding to barrister A.E. McPhillips at St. Andrew’s Cathedral in 1896. Her bridesmaids wore dresses of white China silk trimmed with silver braid.

Two O’Reilly weddings, Caroline Trutch to Peter O’Reilly, and Mary Beresford Windham to Arthur John O’Reilly, show an equal display of wedding splendour. Caroline’s dress was of white brocaded silk embellished with orange blossoms. Mary’s was white charmeuse (a crepe satin material) with orange blossom accessories. A veil of old Brussels lace that had been in the Windham family for many generations completed her outfit. Her going-away gown was made of crimson rattine (a blend of silk and wool), trimmed with black velvet. To top it all off she wore a brown silk hat with decorative ostrich feather and a handsome grey squirrel coat.

When Alice Barnard married John Andrew Mara in the drawing room of Duvals in 1882, her gown was of white corded silk with a train embroidered and trimmed in satin and lace. Alice, had only one bridesmaid, whose dress, surprisingly, was a blue silk and net.

Gertrude Rithet’s wedding to Lawrence Genge in 1904 was another memorable event in the city and provided an unprecedented display of gowns of splendour. Gertrude’s was of white crepe de Chine trimmed with duchess lace, and she carried a shower bouquet of roses, while her bridesmaids’ gowns ventured again into the world of colour. As a general rule, bridesmaids then were attired in traditional whites and creams, which acted as a complement to the white gown of the bride; a dress of colour was thought to be too bold a contrast to an ensemble where the primary purpose was to show off and enhance the bride. Gertrude’s bridesmaids, however, were attired in dresses of Nile green, complete with white chiffon fichus (triangular-shaped shawls) and picturesque poke bonnets.

Not only wedding dresses attracted attention in that long-ago era. When one of Victoria’s native daughters, an O’Reilly no less, was about to be presented at court, her gown was of paramount interest. Kathleen O’Reilly’s presentation dress still exists today but in a somewhat fragile condition and much altered from its original design. It was the very height of fashion, and Kathleen herself in correspondence with her parents described it as her “sparkley white dress.”

For that momentous trip to England and Ireland in 1896 and presentation at the Irish court in February 1897, Kathleen took with her an extensive wardrobe. She described her dress in more detail as “my white ball dress covered with lilies of the valley and a train in white, lined with a delicate shade of apple green, trimmed with tulle, lilies, and white and green bows of ribbon.” She added that it was “so very young looking that a girl of seventeen could have worn it.”105 She herself was already in her late twenties.

A gradual decline in the more flamboyant aspects of fashion down through the years, as well as a lack of interest in the clothing worn by the society families, is reflected in an incident in 1952. An auction was held that summer at Hollybank following the death of Elizabeth Rithet earlier in the year. Many Rithet treasures were put on the block, including Lizzie Rithet’s once-valuable full-length coat of rich Alaska seal with collar and cuffs of mink. In her heyday, Lizzie was often seen wearing it at the most fashionable of society occasions. At the auction, it sold for a mere thirty-five dollars.

• • •

To be well dressed was one thing but, important though that was, there was yet another aspect of life among the elite that was perhaps of equal importance: the business of travel.

As today’s transportation is undertaken with such speed and comparative comfort, it is hard to imagine the inconveniences and hardships that early settlers in Victoria must have experienced. The first to arrive on Vancouver Island were limited to three alternatives—foot, horse, or boat—and each was embarked upon with a great deal of trepidation and discomfort.

Emily Carr describes the situation amusingly in The Book of Small. She claims that “there was no way to get about young Victoria except on legs—either your own or a horse’s.”

Horses did not apparently roam and had to be kept handy at all times for hitching. In Carr’s chapter on “ways of getting around,” she continues:

All the vehicles used were very English. Families with young children preferred a chaise, in which two people faced the horse and two the driver. These chaises were low and so heavy that the horse dragged, despondent and slow.

Men preferred to drive in high, two-wheeled dogcarts in which passengers sat back to back and bumped each other’s shoulder blades. The seat of the driver was two cushions higher than that of the other passengers. Men felt frightfully high and fine, perched up there cracking the whip over the horse’s back and looking over the tops of their wives’ hats. There were American buggies, too, with or without hoods, which could be folded back like the top of a baby’s pram.106

It would seem, according to Carr, that nobody in Victoria was in a hurry, and people drove mainly for the simple pleasure of enjoying fresh air and pleasant scenery.

As the city grew, and especially as the female population increased, owning a more elaborate carriage or hiring one became a necessity among the elite. There were at one time at least ten livery stables in Victoria. The Eureka Stable was a brick building on Pandora Avenue, owned by John Dalby. In addition, Dalby ran a daily stage out to Goldstream.

Bowman’s Stable at Broad and View streets operated with thirty-five horses and carried mail to Esquimalt, as well as running a hack service. Yet another stable was owned by Francis Jones Barnard, who later formed the Victoria Transfer Company for the purpose of constructing and operating “street railways in the City of Victoria and Esquimalt and Victoria Districts adjacent thereto, and carrying on a general transfer, delivery, hack and livery business in the Province of British Columbia.”107

By the 1880s and 1890s, with hack driving a large part of downtown business, health problems were also making themselves apparent. “The cab-stand on Government Street is highly objectionable,”108 announced medical health officials in 1894. The reason was a sanitary one: with horses occupying the site for most of the day, a great deal of manure would accumulate and, when it dried, various unpleasant pieces of refuse could be seen blowing in all directions whenever there was a strong wind.

Three years after the establishment of the Victoria Transfer Company in January 1883, the company had become prosperous. Beginning with a mere fifteen horses, six buggies, and four carriages, by 1886 it consisted of “large and commodious stables covering 66 x 190 feet, at a cost of about $8,000.” The stables still had a “scarcity of room for their large and continually increasing stock of horses, carriages and wagons.”109 Stock by then included over sixty horses, twelve hacks, thirty buggies and phaetons, eight omnibuses, and a number of wagons. The new omnibuses, although at first running at a loss, were gradually becoming very popular with the public at large.

By far one of the most enterprising of the carriage and hack businessmen was George Winter. In colonial days, he had been coachman to two royal governors, Kennedy and Seymour, and had later driven for Lieutenant-Governor Trutch. After Trutch left office in 1876, Winter decided to go into business for himself, but still contracted to drive for two later lieutenant-governors, Richards and Cornwall. George Winter was born in 1839 in England and joined the British navy in his teens. He arrived in Esquimalt Harbour aboard HMS Bacchant in 1861 and, like many others before him, decided to jump ship and join the Cariboo gold rush. He soon tired of the miner’s life, however, so he returned to Victoria, married Margaret Orrick, and decided to settle. When he became coachman at Cary Castle, he and his family lived in a cottage on the grounds. Later, the Winters moved to Ross Bay and there George was able to keep horses and have space for his own carriages, once he was in business on his own. He employed a large staff to keep his carriages in immaculate condition, their brass and plate-glass lamps highly polished at all times.

Soon it became something of a status symbol in Victoria to hire a Winter carriage. They were, after all, the very last word in elegance and the company claimed it could provide “conveyances for every occasion.” For dances, the theatre, weddings, or christenings, a Winter carriage was essential. To be seen driving in one, with a coachman dressed in blue, brass-buttoned livery, was to have arrived. Another attraction of Winter Carriages was the fact that they catered to their clients for specific occasions. For weddings, the carriage conveying the bride would be lined with white satin ruffles. In winter, when the snow was knee-deep, a Winter sleigh could be hired complete with bells, blankets, and heavy fur robes. Hot bricks tucked under the feet were an added touch as sleighs set off into the country. If stops were made along the way at a roadhouse, the gentlemen in the party would down a whisky or two while warming their hands around a pot-bellied stove. Port or sherry was taken outside to the shivering ladies, as it was not thought appropriate for a lady to be seen inside a bar. Were she to enter one, her reputation would suffer irrevocably.

Winter carriages were always strongly in evidence for all the most important occasions in Victoria’s history. In 1876, when Lord Dufferin visited the city, the newly operating Winter Carriages was given a boost by an increase in business. Again, in 1882, when the Marquis of Lorne and his wife, Princess Louise, daughter of Queen Victoria, came to Victoria for an extended time, George Winter’s carriages were much in demand for all the social events around the city.

When the Native Sons group gave their first formal ball in the Assembly Hall on Fort Street in February 1900, Winter carriages were seen on the streets en masse. All elegantly decorated, the horses pulling the conveyances clip-clopped up and down Fort Street, delivering the elite to the ball. When the festivities finally ended around 3:00 AM, the coachmen roused themselves from a short nap (and perhaps a short nip!), picked up their passengers, and drove them home in style.

Winter Carriages officially operated the livery and hack stable on Fairfield Road in Ross Bay from 1884 onwards, although George Winter was in business for some years prior to that. The property remained in the possession of the Winter family until 1921.

The tradition of operating carriages stayed in the Winter family through the next generation. One of Winter’s sons, George junior, became coachman to James Dunsmuir at Burleith. Another son, Robert, was coachman for Judge Paulus Irving. The two brothers often worked together conveying the Dunsmuir and Irving children to school in their one-horse, two-wheeled traps. Later in the day, the Winter brothers would don full livery for a more elegant carriage ride, escorting Mrs. Dunsmuir and Mrs. Irving to their at-home visits around town.

The O’Reilly family also patronized the Winter stables on numerous occasions, and were it not for the coming of the automobile in the early years of the twentieth century, the tradition of Winter carriages might have continued for much longer in Victoria. Young George Winter died of pneumonia in 1909 at age thirty-four, and his father died two years later, shortly after celebrating his seventy-second birthday. His obituary stated that “he was always known for driving the ‘very finest on the road.’”110 By then, the era of the carriage had already passed, marked perhaps by the dawn of the new century.

Victoria had said farewell to the gallant horse, and horseless carriages were now on their way. The very first one, a steam-powered Wolseley, had in fact been seen in BC back in 1899. It was owned by a man in Vancouver, and the Colonist reported then that its appearance on the streets merely confirmed that the end was near for the horse-drawn carriage.

Karl Benz of Germany had produced a three-wheeled vehicle in 1885 with the benzine engine placed over the rear axle, following the introduction of the internal combustion engine. Meanwhile, in North America, the first practical car was being built in a barn in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1892, by Charles E. Duryea, and the Daimler Company had introduced the Panhard car into France by 1894.

Others were also experimenting in the automobile world, including Elwood Hayes, George Selden, and Dave Buick. And, considered by far to be the most amazing, was Henry Ford’s first car, a gasoline buggy developed in 1893. It later proved its worth by travelling at a phenomenal twenty miles an hour.

In Victoria, certain forward-thinking gentlemen had watched these world events with interest. It is believed that the first car seen on the streets of the city was brought in by a travelling circus in 1899, but the first automobile of note to be acknowledged as such was owned by Dr. Edward Charles Hart, one-time Victoria coroner. His was a 3.5 horse-power Oldsmobile that arrived in Victoria on May 23, 1902, to be driven down Johnson Street the following day by its proud owner. It set Dr. Hart back nine hundred dollars and was capable of achieving speeds of fifteen miles an hour.

The Colonist had stated as early as 1895 that “what with the bicycle and the motor carriage, the horse is indeed becoming obsolete.” With the arrival of Dr. Hart’s machine, and that of A.E. Todd a year later, the demise of the horse was inevitable.

Albert (Bert) Edward Todd, son of salmon-canning magnate Jacob Hunter Todd and one-time mayor of Victoria, was a fanatic when it came to the automobile. He could hardly wait for his steam-driven car to arrive from San Francisco on the morning of May 26, 1903. Imported to Victoria by inventor Bagster Seabrook, it was built by the White Sewing Machine Company of Cleveland, Ohio.

Accompanied by H.D. Ryus, Todd immediately took his new car on a trial run from Victoria to Shawnigan Lake, logging and timing the whole adventure. The fact that the journey was made without insurance, driver’s licence, registration, licence plates, windshield, or fenders was of little consequence. Todd had made history. It was not until the following year that the provincial government introduced licensing with an annual fee of two dollars. The Motor Vehicle Speed Regulation Act then required owners to attach the number of their permit in a conspicuous spot on the back of their vehicle so that it was clearly visible during daylight hours. The licence plates were made of leather.

There were thirty-two licensed car owners on the roads by the end of 1904, and Bert Todd held licence number 13. His dedication and contribution to all road-pioneering pursuits in the early years of the twentieth century earned him titles such as “the father of tourism in British Columbia” and “Good Roads Todd.” Certainly his courageous belief in the automobile as something more than a frivolous toy for the rich and privileged had contributed to its eventually becoming a part of everyone’s life. He was convinced it would one day shape the economy, geography, and social aspects of the province.

Although he would eventually prove to be right, in the beginning the automobile was little more than a plaything for the very rich, enabling them to jaunt around the countryside in style. Those who wanted to speed (and there were many!) were limited to a reckless ten miles an hour within city limits or fifteen in the country.

The first hundred registrations in Victoria included many members of high society who were eager to join in this latest craze. Most owned a car within the first ten years of the new century.

Mr. and Mrs. H.D. Helmcken, and D.D. McTavish on the left, with the Helmckens’ Pierce Arrow automobile, 1907.

IMAGE 1981-019-052 SAANICH ARCHIVES

The Butchart family was particularly fond of the automobile. R.P. Butchart, known as “Leadfoot Bob” because of his tendency to drive at breakneck speeds, obtained licence number 11 on May 14, 1904. A note attached later to that registration reads, “Broken Up 8th May 1907.” Many of Butchart’s early vehicles met a similar fate.

Jenny Butchart was one of the first women to own a fashionable electric car, which became very popular with the ladies of Victoria. They were advertised by BC Electric at first as being “clean, safe, simple and economical.” Perfect for theatres, weddings, and all social functions, because one could arrive in immaculate condition, which was, apparently, “so impossible with a gas car.”

Bert Todd and sisters out for a drive, c. 1910.

IMAGE (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION) GIVEN TO AUTHOR BY THE TODD FAMILY FROM THEIR COLLECTION

Elizabeth Rithet was another woman who favoured the electric car. She had a shiny black model with white-spoked wheels. The windows were of beveled plate glass, etched with designs of roses and tulips. The interior of the car contained beautifully upholstered blue velvet seats and sometimes glass vases full of freshly cut flowers. Their presence did not stop Lizzie from driving at high speeds around the streets of Victoria, paying little or no attention to others on the road. Her children claimed that she drove her car with the same wild abandon she always showed when riding her horses.

Just as stables offering hack services had once been big business, so did the business of supplying automobiles become an important part of the town’s commercial life. Two enterprising brothers by the name of Hutchison established an “automobile livery” where one could hire vehicles such as a five-passenger White Steamer (with chauffeur) for a fee of four dollars per hour.

By 1906 Cadillacs were also available for hire, and the Colonist was carrying advertisements for the amazing “self-starting Winton,” a vehicle that enabled its driver to actually start it without leaving his seat. No more back-breaking cranking was necessary, as long as the owner could part with twenty-five hundred dollars to purchase the beast.

J.M. Wood and Thomas Plimley both opened garages in town, and Plimley’s became the agent for Humbers and Singers. Plimley even installed a machine at his garage for “restoring the spirits of depressed tires” and announced, “the public are invited to help themselves to wind at Mr. Plimley’s expense.”111

With automobiles becoming more and more popular, the Hutchison brothers reported they would soon be opening a factory to build them in Victoria. Not long after that announcement, an automobile club was formed among the early car owners, with Bert Todd elected as first president. There were soon approximately twenty cars and ten motorcycles on the roads of Victoria, and even the May 24 celebrations were now billed as the “horse and automobile parade.”

Many vehicles met an early demise, mainly due to road conditions, which were often atrocious. Intrepid early travellers, including men like Todd, Butchart, Hal Holton, and Dr. Garesche, continued to pursue motoring with increased enthusiasm, and it was their dedication that eventually led to road improvement and Victoria’s recognition as a major tourist centre.

By 1910, yet another form of transportation was known in Victoria. William Wallace Gibson made a short and somewhat undignified attempt at notoriety by flying his homemade biplane a short distance and then crashing into a tree on Lansdowne Field in September that year.

No matter the end result, it was just one more indication that the world was getting smaller and the former colony no longer so isolated.

• • •

“Our house was full of company,” wrote Martha Cheney in her journal in September 1853. Her statement was indicative of a lifestyle among the settlers from the very beginning. They liked to entertain and, what is more, they enjoyed writing about it.

Martha Cheney, the young girl who arrived with her aunt and uncle, the Blinkhorns, in 1852, kept a journal peppered with social chit-chat. It is just one of many documents still existing today that enable us to eavesdrop on thoughts, experiences, and conversations in Victoria over a century ago. Although her writing style is sometimes awkward and immature, it does allow the reader to view life as it once was.

“In the afternoon old Mr. Muir came in, and in the evening presently in came John and Archibald Muir. They stayed all night, and then between 9 and 10 o’clock at night, just as we were going to bed, in came Mr. Swanston, Mr. Skinner, Captain Grant and Captain Cooper, . . . a fine houseful [sic] some had to go up in the loft to sleep.”

Martha also tells of other events. In November 1853 she recalls an earthquake in Victoria. “In the evening we felt a Shock of an Earthquake, which shook the whole house, and which nearly took us off our feet. It was about 5 o’clock.”

That same year, “there was a theatre on Board the Man of War Trincomalee. Captain and Mrs. Cooper and myself were invited to see the Scene and of course went. Mr. and Mrs. Langford and family, the Governor and his family, and Mr. and Mrs. Skinner, and the Gentlemen from the Fort, went on board about 6 o’clock in the evening.”112

An indication that despite the isolation of settlers, there was also a fierce determination to maintain a normal social life is seen in Martha’s words in March 1854: “Snow, Hail, Rain, and Blowing a hurricane at times all day. [Nonetheless] Mr. and Mrs. Langford, Mrs. Skinner and her babe, Constance Langford Skinner, came over walking from Colwood that miserable day to see us. They were almost Frozen they stayed all night, then went back the next day [which was] fine but very wet.” Martha Cheney Ella lived in Metchosin, some distance from the Skinners and Langfords in Esquimalt. In another interesting insight into that Victorian way of life, Martha continues to refer to her new husband as “Mr. Ella” for some time after their marriage. And later, when her husband was sick with dysentery, she describes it in the following words: “After we got him home, we sent for the Doctor, he came next morning, bled him and gave him medicine, kept in bed until the next Thursday, which made him very weak indeed. I was taken very ill myself with the same complaint, was in bed for two days, was very weak.”

Letters within the Douglas family are equally enlightening, giving clear insight into the contrasting character traits of James Douglas himself. His overbearing and extremely strict attitude to his only son, James, with constant reprimands on behaviour, educational pursuits, penmanship, and careless habits, is very different from the heartache he expresses when his youngest daughter, Martha, leaves Victoria for schooling and travel in England.

He constantly scolds James with harsh words: “Several of your letters have come to hand, none of them carefully written, either as regards style, orthography or penmanship. They are, in fact, full of blunders, words misspelled, omissions, not of words only, but of whole phrases; errors which a youth of your age ought not to make, and could so easily rectify, were it not for the most inveterate habits of careless indolence which you seem to have fallen into. It is very painful to have such remarks to make on your letters, every time that I write; you appear to have very little regard for my feelings, or you certainly would strive to get rid of these careless habits, which are a perfect torture to me.” And concerning his fatherly advice on the subject of marrying too young, he emphasizes his thoughts with the words “Remember this counsel and be wise!”

By contrast, he tells Martha how desolate both he and her mother are after she leaves: “My dearest Martha, I hurried up from the garden gate where I bade you adieu to comfort Mamma—and found her in a burst of uncontrollable grief. I caught her in my arms, but her heart was full. She rushed wildly into her room and, casting herself upon the bed, lay sobbing and calling upon her child. Mamma was at length exhausted, and then I poured in words of consolation, and then drove out to see you pass out of the harbour.” Later, “Last night after prayers, in which you were earnestly remembered, Mamma burst into tears and had a good cry; which relieved her feelings, and she was soon all right again.”

Waxing somewhat poetic, this often hard man wrote to his daughter of a horseback ride: “I drove out to Rosebank—the woods were charming, fragrant with the perfume of numberless trees and plants and lustrous vernal beauty. Wondrous are the works of God who can show forth His glorious acts.”

And perhaps even more surprising, Douglas wrote these words to his youngest daughter: “I have placed a large, beautiful apple on the table in your bedroom. It makes me fancy that you are here—though a mere delusion it alleviates the pain of absence.”

The Crease family also takes us on a journey of discovery into the Victorian era. In 1889, daughter Josephine Crease complains about the frequency of social obligations: “we have to go! Bally nuisance.”

A few years later, Josephine describes something of the snobbish attitude toward outsiders not considered to be of good family with all the right connections: “Lindley brought a Mr. Hopkins, a complete stranger into dinner,” she says. “E. Shrimp, and A. [family members] behaved very shockingly for the stranger’s benefit.” Not only could the upper class not abide strangers in their midst, they also had very little understanding of or patience with their Chinese servants. “No Chinaman, left without a word! Oh dear.”

And Nellie (Todd) Gillespie, a sister of Bert Todd, remarked: “I remember one very good Chinaman we had. He went off to China and then came back again. My father said, ‘Times are very bad now. I can’t pay you as much as I did. So the Chinaman came just the same and after a while I said to him, ‘Why don’t you make those nice little jelly tarts you used to make?’ He said, ‘Oh, $20 Chinaman not make tarts like that. Only $25 Chinaman make them.’”

Kathleen O’Reilly’s words are as vibrant and alive today as they were when first written. When she was eleven years old, she described simple day-to-day activities at Point Ellice House to her father: “The day before yesterday another brood of chickens came out. The hen had her nest somewhere and they are now running about the yard.” She writes of visits to “Uncle Joe” (Joseph Trutch) and tells her father: “Jack [her brother] is reading to Mamma who has a headache.” Her words to her parents from Tourin, Cappoquin, in County Waterford, Ireland, in 1897 are particularly interesting:

The drawing room was a very pretty sight. The rooms and corridors of the castle are simply beautiful and perfect for entertaining . . . Lord Cudogan is a dear little man . . . I was rather anxious about the ordeal of being presented, and I had so many instructions about curtsying first and then presenting your left cheek for the Lord Lieutenant to kiss and I was told to do it all very slowly as some people get so frightened that they rush first past the dias [sic] where all the Vice Regal party are standing. I gave my card to the officer at the Throne Room door who said, ‘Curtsy first, won’t you?’ in a sort of sympathy tone.

Then my name was simply shouted out which was rather disconcerting in itself, but when I got in front of Lord Cudogan, a man in the party said ‘The young lady from British Columbia,’ and one of the aides performed a sort of war dance! I entirely forgot about the kiss, and His Excellency seized my hand and drew me toward him—they say he never really kisses anyone which is very wise of him I think. Then I made my bow to Her Excellency and passed on. She smiled sweetly.

At the beginning of Kathleen O’Reilly’s 1897 diary, she wrote a simple poem. Whether of her own creation or written by someone else and simply enjoyed by her, it helps explain her reluctance to ever trust a man enough to become his wife:

You call me sweet and tender names,

And fondly smooth my tresses,

And all the while my beating heart,

Keeps time to your caresses.

You love me in your gentle way,

I answer, as you let me,

But Oh! There comes another day,

The day when you’ll forget me.

John Andrew Mara, who married Alice Barnard in 1882, also kept interesting diaries. Mara was an adventurous man who had walked across the continent as a member of the famous Overlanders. In his youth he had crossed mountains and battled blizzards, as well as sailing an ocean, and later fought numerous battles in the political arena.

He describes the opening of the new Parliament Buildings in February 1898, a big social event in Victoria. It was apparently “showery and cloudy” that day. “The new Parliament Buildings opened by Lt.-Gov. McInnes at 3 PM. Dr. Helmcken and I occupied seats on the Throne with Mr. Speaker Higgins. There was a big crush and a great deal of confusion. The Chamber looked well, but some of the arrangements were out of place.”

Peter O’Reilly’s diary that year makes mention of the same occasion: The O’Reillys had “good seats” and the Arion Club performed.

A later diary of Mara’s describes a meeting he had with Peter O’Reilly in London soon after the death of Caroline O’Reilly: “Saw O’Reilly and Frank at the Euston Hotel—the former is terribly cut up over the death of his wife.”

Peter O’Reilly’s grief seemed to be the topic of many conversations. Even Lady Macdonald, in her continued correspondence with the O’Reillys after her visit to Victoria, remarks to Kathleen: “he looked so sad and changed after his grievous sorrow that all who met him were distressed—those especially who know what he had lost in your dear mother.”

Meanwhile, Mara’s diaries also give a glimpse into the travels abroad of a typical upper-class family. In 1900, John Mara, Alice, and their two children, Nellie and Lytton, travelled to London, primarily to settle Nellie into school there. They also took time to do a little sightseeing in London. “In the afternoon, we went to the Albert Hall Concert. The size of the Hall and the large attendance was a surprise to Nellie . . . We saw the Horse Guards changing . . . [and] then took Nellie to the Art Gallery.” They also visited the Monument and London Bridge and were particularly impressed with St. Paul’s. A visit out of London to Oxfordshire took them to Blenheim “to see the Meet . . . Alice and the children had never seen a Meet before.”

In February, the Mara family attended Puss in Boots at the Garrick Theatre, and they also took time for some shopping. An umbrella at Dickins & Jones cost Mara one pound two shillings and sixpence, whereas his golf suit from Hope Brothers cost him three pounds nine shillings and sixpence. In addition, the family frequently visited the Army & Navy Store for wool shirts and socks. With his political interests, Mara went to the House of Lords to sit in on debates, and was ever conscious of the happenings in South Africa as news of the war reached London on a daily basis.

George Winter Carriage outside Cary Castle, George senior on left.

IMAGE B-00472 COURTESY OF ROYAL BC MUSEUM, BC ARCHIVES

“Good news from South Africa,” Mara announced on February 18, 1900. Then on March 1, “News of the relief of Ladysmith received at 10 a.m . . . The whole of London frantic with joy. Business in the city practically suspended. All traffic stopped in the vicinity of the Mansion House.”

Clearly, the early residents of Victoria, with their connections and interests around the world, were far from isolated despite living, as they did, on the far side of the Rockies. Their pasts and their continued interest in travel, plus their regular correspondence with friends and relatives around the world, kept them abreast of the times and in touch with world affairs.

(The quotes in the conversations section of this chapter come from the following sources: the Diary of Martha Cheney Ellis, the Douglas Correspondence, the Crease Correspondence, the O’Reilly Collection, the article by Willard Ireland on Walter Grant, and the Diary of John A. Mara, which are all provided in the bibliography.)