Trial by ordeal: forcing the accused to walk on hot metal was standard before proper trials were established

Since ancient times the scientifically minded have searched for reliable ways of determining the cause of suspicious deaths and identifying those responsible for committing serious crimes. In the days before the advent of DNA profiling and all the other high-tech tools of modern forensic science, the detection of crime depended almost entirely on the luck and dogged determination of the investigator. Unfortunately, there were those both within the legal system and without who doubted the reliability of the emerging science or who attempted to block its progress for selfish ends. In modern times such reservations were swept aside as forensic detection proved that it had the power to nail a suspect.

It has been said that the patron saint of forensic science is St Thomas the Doubter, who is as loyal a disciple as his brothers but cannot bring himself to accept as a fact anything he has not seen with his own eyes. Of the Resurrection of Jesus he says, 'Except I shall see in his hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the print of the nails, and thrust my hand into his side, I will not believe.' (John 20:25)

He remains a good model for forensic scientists of all faiths and those of none.

The Bible has more than its share of murders, rapes and random cruelty, but it is safe to assume that the first homicide must have occurred even further back when the first Neanderthal crushed the skull of his neighbour with a rock or animal bone in a dispute over food, water or a mate, proving that human nature has changed little over the millennia. However, in the course of human evolution we became social animals and acquired the need for laws and ways of enforcing the laws.

Justice or a sense of fairness demanded a way of proving innocence or guilt which was initially served by trial by combat and trial by ordeal, but was ultimately determined by an independent judicial system of trial by judge or jury.

Trial by ordeal: forcing the accused to walk on hot metal was standard before proper trials were established

Forensic science, meaning science in service to the law, is a comparatively recent discipline but it has evolved in faltering stages since ancient times. The Roman physician Antistius performed one of the earliest recorded post-mortems to determine which of the 23 stab wounds that felled Julius Caesar was the fatal blow. But the first recorded reference to forensic detection dates from the Middle Ages. A Chinese book called Hsi Duan Yu (roughly translated as The Washing Away of Wrongs) described the distinctive marks and wounds which reveal the cause of death, accidental and otherwise.

During the Renaissance, Fortunato Fidelis learned how to distinguish between accidental and deliberate drowning, while his fellow countryman Paolo Zacchia catalogued fatal wounds by blade, bullet and ligature in order to establish a criteria for determining whether a body had met its end by suicide, natural causes or murder. His findings, together with those of the anatomist Morgagni, can be seen as cementing the cornerstones of modern pathology.

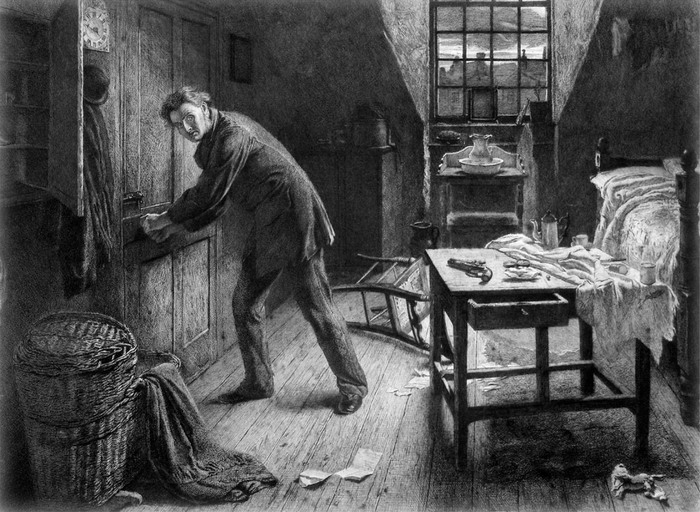

But although the infant forensic sciences were already evolving, cynicism and bullheadedness continued to plague criminal investigations. Even when there was a profusion of physical evidence, its significance was rarely understood or appreciated. When the early 16th-century Parisian aristocrat Lady Mazel was found stabbed to death in her bed with an embarrassment of clues to choose from, the authorities displayed an alarming lack of imagination that led to the false imprisonment and death of an innocent man.

The servants had been forced to break down her Ladyship's bedroom door after she had failed to respond to their entreaties. Her strongbox had been rifled and a gold watch was also missing, but the curious aspect was that her door possessed a spring lock which automatically locked from the inside so no one could enter during the night.

A clasp knife was recovered from the fireplace and a cheap lace cravat and a discarded napkin were found among the rumpled bedclothes. The latter had been folded to form a makeshift nightcap. Assuming it to belong to her Ladyship's attacker, it was passed among the servants until it was found to fit her valet, a man named Le Brun. It later transpired that the cravat had belonged to a footman named Berry who had been summarily dismissed, but this fact was ignored as irrelevant. As Le Brun did not have any incriminating blood spots on his clothes it was assumed that he had let an accomplice in through the kitchen door and then into her Ladyship's bedroom using a skeleton key that he was known to possess. A more exhaustive search of the house led to the discovery of a bloodstained nightshirt in the attic which, inconveniently for the authorities, did not fit their suspect. Nevertheless the hapless Le Brun was tortured and died from his injuries.

THE REAL MURDERER DISCOVERED

The following month Berry, the footman, was arrested in the vicinity on an unrelated matter and found to have Lady Mazel's watch on his person. He freely confessed to her murder and described how he had slipped unnoticed into the house and hidden in the attic where he lived for several days on bread and apples. He had waited until the household had departed for church on Sunday morning before emerging from his hiding place and lying under Lady Mazel's bed until she retired that night. For some reason he had felt the need to make an improvised nightcap from a napkin which had fallen off in the struggle after her Ladyship awoke to find him rifling her strongbox. After stabbing her he hid the bloodstained nightshirt in the attic in case it was found on him as he left the house, but he had evidently forgotten about the nightcap.

Had the authorities made a thorough search of the attic they might have also found discarded apple cores and breadcrumbs which, together with the nightcap and bloodstained nightshirt, would have confirmed the presence of an uninvited overnight guest. The valet would have no need of a makeshift nightcap, nor would he have worn a cheap cravat, but the mere mention of the dismissed servant should have aroused suspicion.

Lady Mazel's footman described how he had hidden in the attic for several days

Such incidents demonstrate that those who investigate crime and administer justice must be alive to all the facts and the possibilities they present and not simply set out to select those which support their personal theory. The application of forensic science alone cannot ensure that the guilty are always identified and the innocent exonerated.

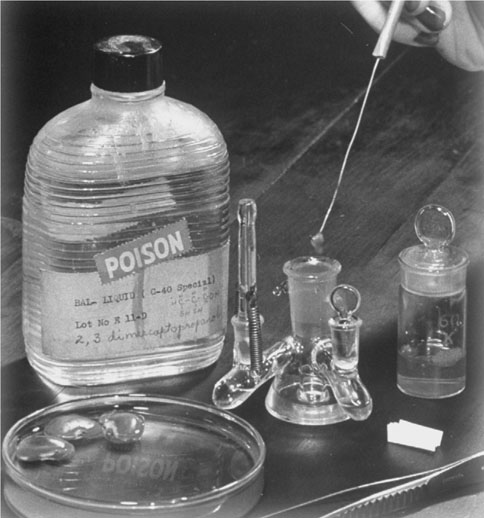

At the time of the Renaissance, poisoning was practically an art form. Since ancient times it had been the preferred method of dispatching both enemies and tiresome lovers by virtue of it being practically undetectable and the fact that it could be administered surreptitiously, without recourse to violence. But even in the age of scholarship and science, techniques for detecting its presence were still woefully inadequate and unreliable.

The inquest into the death of the Earl of Atholl in 1579 is typical of the period. Suspecting poison, an attending physician cut open the corpse and dipped his finger into the contents of the nobleman's stomach. A single taste was sufficient to confirm the presence of poison and make the doctor very sick indeed.

By the early years of the 19th century there was a profusion of new poisons which could be purchased freely over the counter and which even the most renowned chemists had difficulty in detecting. Many, such as arsenic, strychnine, morphine and nicotine, were used in small doses for medicinal purposes, which made it difficult to determine whether they had been administered innocently or with malicious intent. Moreover, some occurred naturally in the body post-mortem, a little-known fact which had led to the false conviction of many innocent individuals. As late as the 19th century it was a revelation to even the most experienced chemists that arsenic can seep into a coffin from the surrounding soil and be absorbed into the body, a process which led at least one physician to conclude that a body he had exhumed had been unnaturally hastened to the grave by the administration of deadly poison. The deceased man's innocent son was consequently accused of the crime and executed.

Inevitably it became a matter of urgency to develop reliable new techniques for the detection and identification of toxins in the body. Fortunately, necessity again proved to be the mother of invention and in 1813 a precociously gifted Spanish medical graduate known simply as Orfila found himself faced with a unique problem. Having promised his eager audience of fellow students in the Paris School of Medicine that a certain reaction would occur when arsenous acid was mixed with various liquids, he was shocked to discover that it was not so. Further experiments using other liquids also failed to produce the expected results, whereupon the embarrassed lecturer dismissed his class and spent the rest of the day scouring the shelves of the university library in search of the solution.

In the early part of the 19th century a profusion of new poisons was freely available at the chemist

After hours of fruitless inquiry Orfila had his 'eureka' moment and realized that he couldn't find the answer for the simple reason that the first toxicology textbook hadn't yet been written. So he set himself the task of doing just that and within the year had published his seminal Treatise On Poisons, thereby earning himself a place in the history of forensic science and severely curtailing the lucrative trade in poisonous philtres, pills and potions at a stroke.

In our age of routine DNA testing, spectroscopic analysis and global fingerprint databases it is almost impossible to appreciate the degree of suspicion with which the emerging science was seen by both the judiciary and the general population. The Church repeatedly urged Christians of all denominations to spurn the new disciplines which they saw as tantamount to questioning the will of God.

Small doses of poison were routinely used for medicinal purposes

In many countries suspicion alone was enough to subject a suspect to torture in the hope of extracting a confession and there was no way of knowing if it was a genuine declaration of guilt or offered simply to end their suffering. Even judges could be blinded to reason by their unswerving allegiance to the letter of the law, which they saw as chiselled in stone, sacred and absolute. In one of the first studies of crime and criminals (Mysteries of Police and Crime, 1898), the author, Major Arthur Griffiths, recounts the true story of a Maltese judge who, in the early years of the 18th century, had knowingly condemned an innocent man to death because the circumstantial evidence against him was compelling. The judge knew the man to be innocent because he himself had witnessed the crime and had seen the murderer with his own eyes, but his blinkered loyalty to legal formalities and inflexibility prevented him from acting as a witness in the case and publishing what he considered to be 'privileged information'. So he had ordered the suspect to be tortured and then executed following the extraction of a forced 'confession'.

Such incidents were comparatively common in the centuries before the adoption of the central precept of European law, which states that a suspect is considered innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

It wasn't until 1752 that the first true test case for the emergent science made its appearance in a European court of law. At the trial of the poisoner Mary Blandy, expert witness Dr Anthony Addington was asked how he could prove that a packet of white powder found at the defendant's home was arsenic. He replied that it was of the same consistency and texture as arsenic and that it had produced thick white plumes of vapour when placed on a red-hot iron just as arsenic would do. Therefore it followed that the substance which had been found on the defendant was indeed arsenic. This pronouncement qualifies Dr Addington as the first expert witness in a modern trial.

Confessions were extracted by torture at the hands of the Spanish Inquisition (c1500)

SCIENTIFIC DETECTION

The first recorded example of scientific detection occurred in Scotland 34 years later. A young pregnant girl had been found with her throat cut in an isolated cottage on her parent's farm in Kirkcudbright. The local doctor concluded that the killer was evidently left-handed as the cut had been made from right to left and there were further clues in the vicinity which invited investigation. A trail of footprints were found on soft boggy ground nearby, with deep impressions at the toe indicating that whoever had made them had been running from the scene. Drops of blood were also found, as was a bloody handprint on a stile over which the murderer must have climbed in order to escape.

Plaster casts were made of the prints, which gave the police a template for comparison and served to preserve the distinctive features of the boots, which had recently been mended and shod with iron nails. All adult males on surrounding farms were asked to submit to an examination of their boots and shoes, which produced a positive match with those owned by a left-handed labourer named Richardson. But he appeared to have an alibi – he was with two other farmworkers at the time of the crime. However, when questioned, they recalled that he had left them to gather nuts in a wood near the girl's farm and returned half an hour later with a scratch on his face and mud on his stockings. A search of his cottage produced the stockings, which turned out to be both muddy and bloodstained, prompting a comparison to be made with the mud in which the footprints were found. Both contained a trace of sand which was unique to the boggy ground near the victim's farm. Faced with such indisputable physical evidence Richardson had little choice but to confess in an effort to unburden his conscience before his execution.

The fact that the crime occurred in a remote rural region meant that the police could safely assume that the culprit was a local man and so had only to eliminate the innocent from a small number of suspects to identify the guilty party.

By the mid-19th century England had its first full-time professional detectives and America had its Pinkerton agents, but modern forensic science was still in its infancy and was neither entirely trusted by the police nor the public, which meant that juries could ignore circumstantial evidence if they disliked the face or manner of the accused. In its place were well-meaning but crude, impractical attempts at criminal classification such as Bertillonage, which, in the days before photography, used a complex system of physical measurements to identify criminals, and the spurious science of phrenology – determining a person's criminal inclinations from the shape of their skull and the measurements of facial features (which led to the evil of eugenics). Both were soon rendered redundant by the much more reliable mapping of fingerprints.

In the 1870s a British civil servant in India, William Herschel, had been entrusted with organizing pension payments to ex-soldiers, but couldn't distinguish native applicants on facial features alone. Anxious that he shouldn't pay the same person twice, he devised a method of infallible identification which required the applicant to sign for their money with a thumbprint in ink – a practice thought to have been originated by the ancient Chinese. Shortly thereafter a Scottish physician, Dr Henry Faulds, saw the potential of fingerprinting in the fight against crime and devised a system for categorizing and classifying prints according to the whorls and ridges which made each person's fingerprint unique.

But until the late 19th century, when fingerprinting was proven to be both reliable and practical, criminal detection was a simple matter of dogged persistence, luck and intuition. Suspects were eliminated only if they could furnish an alibi corroborated by witnesses of good character, while circumstantial evidence was often sufficient to condemn a man to imprisonment or death. The authorities relied on a criminal's compulsion to confess rather than physical evidence.

The father of fingerprinting: William Herschel

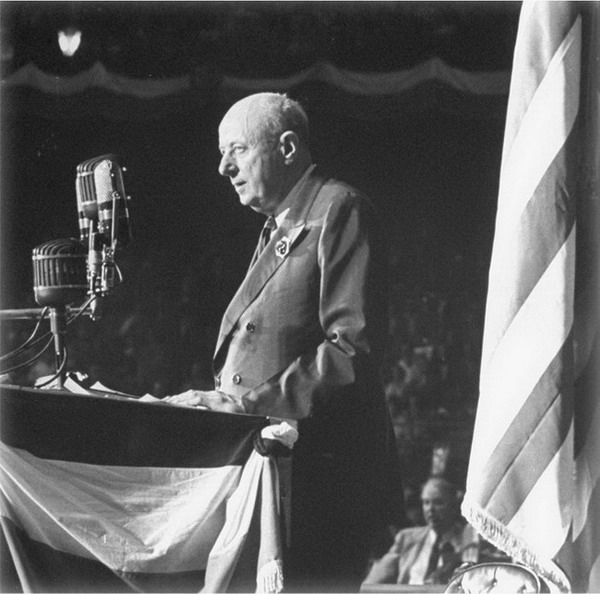

Then, in 1924, a youthful state's attorney made American legal history by demonstrating that, in the absence of reliable eye witnesses, evidence alone can be used to reconstruct a crime.

In February of that year Harold Israel, an itinerant, alcoholic First World War veteran, was arrested in Norwalk, Connecticut on suspicion of having murdered a priest in nearby Bridgeport. Father Hubert Dahme had been slain in full view of several witnesses on Main Street by a single bullet from a .32 revolver, the same calibre weapon as was found on the soldier when he was questioned. Under unrelenting interrogation Harold broke down and confessed to killing the priest out of sheer desperation and despair. But the State's Attorney, Homer Cummings, was uneasy. As he looked over the evidence a number of unanswered questions nagged at him until he felt compelled to revisit the scene and question the witnesses himself. Why, he wondered, had Israel held onto the revolver when selling it would have brought the starving soldier a hot meal and a comfortable bed in a warm boarding house instead of the draughty dilapidated room he shared with two other veterans in a freezing flophouse? And why did the soldier shoot Father Dahme in the back if he was as angry as he claimed to be? Surely he would have confronted the priest and poured out his rage face to face?

When Cummings made further enquiries he discovered that the police had found not one but dozens of spent .32 shell casings at the ex-soldier's lodgings. Apparently all three men had been in the habit of shooting their revolvers from the window at empty liquor bottles for target practice. Any of the three could have fired the fatal bullet and, if not, there were millions of mass-produced .32 revolvers in circulation at that time with no reliable method for determining which weapon had fired a particular round.

As soon as the police had extracted the confession, Israel was allowed his first full night's sleep in days and the next morning retracted it, claiming that it had been forced from him under duress. But his alibi was weak.

He claimed to have been at the movies watching a film called The Leather Pushers, but when pressed he couldn't remember the plot. Cummings asked at his own office if anyone had seen the film and those who had shared an equally vague recollection. Low-budget production line 'flicks' in the silent era were not renowned for the strength of their storylines.

Convinced that there was sufficient doubt not to proceed with the prosecution case, Cummings re-enacted the murder on Bridgeport's Main Street with his assistants standing in for the eye witnesses. It was obvious to Cummings that the single street lamp was too far from the spot where the priest had fallen to give the witnesses a clear view of the attacker in the encroaching evening gloom. He would have been no more than a shadow. It would have been impossible even to describe the clothes he had been wearing. No doubt the description published in the newspapers had supplied the details given by witnesses.

DISMISSING THE FINAL WITNESS

The only witness remaining was a waitress at a hamburger diner who claimed that Israel had been a regular customer and that she had waved to him through the window as he passed the diner just before the priest was killed. But when Cummings went inside to question her he noticed that the window was steamed up that time of the evening, obscuring a clear view of the street. Wiping the condensation with his sleeve, the prosecutor found that he still couldn't recognize his own colleagues because of the glare of the street lights on the wet window. Finally, he asked the waitress to wave to him when he passed outside to indicate that she had recognized him. Cummings walked past three times but she failed to acknowledge him every time. Instead she waved to two strangers and one of Cummings' assistants.

Homer S. Cummings who showed that evidence alone can be used to reconstruct a crime

Boomerang (1947) was inspired by the real-life case that Homer Cummings solved from physical evidence alone

It transpired the girl had been encouraged to concoct her story by a lawyer friend with whom she was hoping to share the reward. The charges against Harold Israel were subsequently dropped and he seized his second chance at life, becoming a happily married, wealthy businessman while Homer Cummings rose to become America's youngest attorney general.

The case inspired a Hollywood movie, but the most significant aspect was the fact that it thereafter became common knowledge that every crime scene holds clues that are usually more reliable than even the best-intentioned witnesses. Baffling crimes could be reconstructed from the physical evidence alone and the guilty convicted with confidence.

During the following decades developments in ballistic science provided investigators with the means of matching a bullet or shell casing to a specific firearm. But sex crimes remained stubbornly and frustratingly problematic until science took a quantum leap into the digital age with the discovery and practical application of DNA analysis in the 1980s.

The realization that every individual has a unique molecular fingerprint – with the exception of identical twins – meant that scientists need only a scraping of skin or a drop of blood or saliva to identify the donor. Now, no matter how careful or thorough a criminal might be in eradicating evidence, they cannot avoid leaving a tell-tale trace on their victim or at the scene.

Forensic science is the one branch of science that cannot afford to become complacent. New techniques of crime detection need to be and are being developed and eagerly assimilated by crime prevention agencies.

For example, increased anxiety concerning travel security has resulted in the use of particle analysis equipment being installed at many international airports. All luggage is now routinely swabbed and screened for traces of explosive, as are passengers, who now have to pass through a metal screening arch.

Increased security at airports is now commonplace

Another recent innovation is the use of specialized software which can identify the make and model of the printer which sourced a particular document such as a fake passport, counterfeit currency, ID or ransom note. It can scan the minute bands of light and dark which all printers produce on the suspect item and match them to a specific make and model of printer.

Every new development in the fields of medicine, chemistry and even aeronautics technology is scrutinized and evaluated by leading forensic scientists to see if there is a possibility that it might prove useful.

And thanks to the massive current popularity of forensic science-based TV crime shows there are now more recruits to the ranks of crime prevention and detection agencies than ever before, stacking the odds for the first time ever in favour of a law-abiding society.

Forensic technology may be a comparatively recent development, but the science, or art, of forensic detection is as old as crime itself. Even without the aid of genetic fingerprinting, trace evidence analysis and crime scene reconstruction software, an astute investigator could apply simple scientific methods to solve even the most baffling cases.

One such man was Professor R. A. Reiss, a French criminologist and founder of the Institute of Police Science in Lausanne. During a visit to Le Havre in 1909 Professor Reiss was invited by the local police to assist in the investigation into the murder of a female 'fence', a dealer in stolen goods. The back of her skull had been crushed by a single blow while she sat at a table nursing an empty bottle of liquor, her back to her assailant. An empty cupboard indicated that the motive must have been robbery, but other than that there were no clues – at least that is what the local prefect of police assured Reiss as he knelt by the victim's front door with his magnifying glass in hand. But the professor was a patient and persistent man with an unerring eye for detail. Within moments he had discovered a single drop of blood and was following the trail on all fours down the passage to the room where the body had been found. Apparently the murderer had been nicked by a splinter when he had jemmied open the door and had left a trail of tiny droplets which the gendarmes had overlooked.

Professor R. A. Reiss in Brazil (right, wearing cap) preparing for an excursion in 1913

Reiss's office in 1910

But there was more. Rising to his feet, the professor declared that the killer was a left-handed man who was known to the deceased and that he had killed her after she surprised him rifling through her cupboard in the dark. Asked how he could know this without having been an eye witness, Reiss remarked that it was a simple matter of observation and deductive reasoning. The blood spots were on the left side of the passage and a trail of tiny specks of candle grease were on the right, indicating that the murderer held the tool for prising open the door in his left hand and the candle in his right, which is the opposite of what a right-handed person would do. The fatal blow was on the left-hand side of the woman's head, confirming that the weapon had been held in his left hand.

The empty bottle and smell of liquor on her revealed that the dead woman had been drunk, and the intruder must have known that it was her habit to drink heavily after dark as he had jemmied the door open without being afraid that he would wake her at that late hour. He had brought the candle with him, as the wax spots began at the beginning of the passage, and he had known which cupboard to search, for nothing else had been disturbed. There were a number of grease spots on the rug in front of the cupboard, which proved that he had searched in the darkness.

While the prefect scratched his head and pondered the significance of these clues, the professor took a scraping of the candle grease and deposited it in an envelope together with two hairs he had plucked from the carpet with tweezers. They were too short to have come from the head of the victim and could prove significant once Reiss had a chance to study them under a microscope.

The following day the professor arrived at the prefect's office with a detailed description of the man they were seeking. He was a left-handed sailor who had recently returned from Sicily and could be identified by his red moustache and a cut on his left hand where he had been nicked by the splinter. The short red hairs were evidently from a moustache, a chemical analysis of the candle grease revealed a recipe unique to Sicily and the most likely person to bring a candle from Sicily to the port of Le Havre is a sailor. Inquiries at the port led the police to the only ship to have recently arrived from Sicily, where they found an Italian by the name of Forfarazzo who answered the description Reiss had given them.

The final scene played out like a stage melodrama. Forfarazzo was handcuffed and dragged to the scene of the crime where Reiss presented him with a blank sheet of paper claiming it was a letter in order that the suspect would accept it. Forfarazzo took it in his left hand. A search through his pockets recovered the stump of the candle which was revealed to have the same chemical composition as the candle grease found at the murder scene. Yet still Forfazzo refused to make a full confession until the evening of his execution, when he admitted selling his victim the liquor knowing she would be drunk by the time he returned to relieve her of her cash.

Arthur Conan Doyle could not have found a finer model for his fictional detective than R. A. Reiss (centre)

In past centuries the aristocracy considered themselves to be above the law and as such immune to prosecution. It was not unknown for a member of the nobility to exercise their power over their own servants to confirm their version of events under the implicit threat of dismissal, or to exploit their influence with the local magistrate to overlook an 'indiscretion', such as the murder of a mistress or servant who would have been considered a mere chattel. Even as late as the Edwardian era the authorities were obliged to accept the word of a gentleman without question, until the evidence proved otherwise. But this genteel world began to crumble with the solution of the notorious Praslin affair – the first crime to be solved using a microscope.

In the summer of 1847 the marriage of the French Duc de Choiseul-Praslin and his wife Fanny was under severe strain. The Duc had refused to give up his pretty mistress, a former governess to the nine Praslin children, while Fanny, the daughter of one of Bonaparte's generals, was in no mood to compromise. It was clearly fated to come to a tragic end.

In the early hours of 18 August, the servants were roused from their beds by a hideous shriek issuing from the Duchesse's bedroom and the violent ringing of her bell as she attempted to summon help. The door was barred from the inside and as the servants debated what to do they heard a crash followed by a ghastly silence. Rushing out into the garden, they looked up as the window was flung open and the Duc appeared in some distress. Assuming that he had interrupted an intruder the servants raced back upstairs to give their master some assistance, but when they entered the now unlocked room they saw only the bruised and battered body of the Duchesse, her throat cut, lying amid overturned furniture. Into this chaotic scene marched the Duc, feigning surprise at finding his wife apparently murdered by burglars. The servants knew better than to question their master, but fortunately for them two gendarmes happened to be passing the house that moment and questioned the witnesses before the Duc had time to coach them in his version of events.

In due course, M. Allard, the head of the Sûreté, was summoned and immediately dismissed the idea of an intruder. The Duchesse's jewels had not been taken and no one had seen strangers fleeing from the house, which had been roused by the commotion.

A search of the Duchesse's room led to the discovery of a bloodstained pistol which the Duc readily admitted to be his own. He had brought it with him, he said, to tackle the intruder, but when he saw his wife's body he had dropped it and it must have been kicked under a sofa in the ensuing confusion. The Duc could account for the blood on his nightshirt, too. It must have been soiled, he argued, when he cradled his wife in his arms as she lay dying, but he couldn't explain the presence in his room of a blood-stained knife or the severed cord from the bell-pull on which she had tugged to summon help. In his anxiety to hide the knife and the cord he had evidently returned to his room while the servants were running in from the garden and had hidden them in the hope of disposing of them at a later date.

Even with such damning evidence M. Allard knew that he would have a hard time convincing a judge of the Duc's guilt. All of it could be explained as the result of irrational actions by a grief-stricken husband, while the servants could not be relied upon to give evidence against their master. Allard would have to trust the pistol to tell the true story. Had it been dropped in the blood as the Duc had claimed, or had it been used to bludgeon the Duchesse to death? It was immediately handed over to the most eminent pathologist in Paris, Ambroise Tardieu, who examined it under the revealing lens of his microscope. There were strands of chestnut hair and fleshy tissue near the trigger and on the butt which matched those of the Duchesse. It was clear that the Duc had tried to cut his wife's throat, but when she resisted he had struck her repeatedly with the pistol. During a medical examination toothmarks were found on the Duc's leg where his wife had bitten him in a last desperate effort to be free of her attacker. Faced with the humiliation of a public execution, the Duc swallowed a lethal dose of arsenic and died in agony three days later.