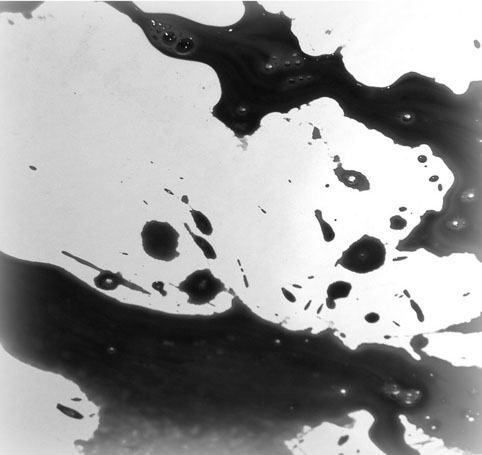

The many bloodstains at this crime scene provide vital evidence

All criminals leave a trace at the crime scene, no matter how careful they might have been or how meticulously they planned their crime. It may be a single hair or fibre from their clothes, a partial fingerprint, the distinctive mark of the tool with which they forced entry into the property, the imprint of their tyre tracks or even microscopic flakes of skin. The challenge for the investigators is to identify which trace evidence is significant and which can be discarded. Equally valuable is the trace evidence that a perpetrator takes away from the scene, which on examination could place them at the location and tie them to the crime.

A dark stain is found at the scene of an abduction, but is it blood? If it is, it could mean that the victim has been injured and the authorities need to know that they are dealing with a ruthless kidnapper who may kill to avoid capture. Or perhaps the abductor was injured in a struggle and the stain could hold a vital clue as to their identity. DNA analysis is costly in terms of lab time and resources and every minute is crucial in abduction cases, but there are serology (bodily fluid) tests that can be done by a CSI at the scene which give instant results.

If an attempt has been made to scrub out a dark, incriminating stain, a single spray of luminol can reveal minute traces of blood which will glow in the dark as a result of the enzyme reacting with the chemical agent in the spray. Unfortunately, there are innocent substances such as potato which react in the same way, as they contain the same enzyme found in the haemoglobin molecules which distribute oxygen through the body in red blood cells. So a second on-site test is done which identifies whether it is human blood, animal blood or another substance with the same enzyme.

A saline-moistened swab is rolled over the stain and then sprayed with a synthetic (monoclonal) antibody such as Phenolphthalein which causes a specific reaction, turning the swab blue if it is positive for human blood. If it is human blood, the question is then whose blood is it? To answer that, a sample must be taken to the lab for analysis, but results can be speeded up by opting for a simplified antigen test which identifies the donor's blood type. Antigens are enzymes which provoke an immune response involving the creation of antibodies to fight infection. People with certain blood types will possess the corresponding antigens so if the victim is AB negative, for example, and the test reveals antigens associated with another blood type then it is extremely unlikely to be the victim's blood. The test is similar to that used to test for compatibility between patients and blood donors.

The most common blood type test is known as the ABO system, which reveals the presence of A-and B-type antigens. Two solutions of antibodies are added to the sample which forces the blood cells containing the A antigens to clump together, isolating the AB groups. The second solution splits the cells containing the B antigens from the AB groups. Blood type O is unaffected by the solution and so is easily identifiable as a group of distinctly separate cells.

BLOOD SPLATTER

It is usually only novelists, poets and historians that talk about blood being spilled or shed. Crime scene professionals know that blood rarely falls drop by drop to form a neat pool around a body but instead spurts from a wound in a gushing stream because of the pump action of the heart, leaving 'satellite splatter', 'spines', 'streaks', 'cast-offs', 'tadpoles' and 'transfer patterns' which to the untrained eye appear to be a sticky mess that speaks only of random violence and confusion. However, for the blood pattern analyst, splatter can be 'read' as easily as any painting, since droplets behave in the same way as projectiles and conform to the principles of ballistics. But unlike a bullet each drop of blood literally explodes on impact when it comes into contact with a flat surface and is distributed according to the velocity, volume, distance, direction and surface texture.

So splatter specialists are trained to recognize how blood will react when dropped and sprayed on every type of surface, including walls, floors, tiles, towels, glass, carpets and even the inside of a vehicle. Not only that but they need to be able to identify correctly the distinctive pattern made by various types of assault including hacking, beating, stabbing, sawing, slashing and cuts inflicted on an attacker in self-defence. They also need to work out how much force was applied as well as the relative position of the assailant to the victim, whether they were moving or stationary, at what speed they were moving and what happened immediately after the attack took place.

The many bloodstains at this crime scene provide vital evidence

Each drop of blood literally explodes on impact

SPLATTER SCHOOL

CSIs are required to attend seminars and specialist courses just like every other professional, but at Professor Herbert Leon MacDonell's week-long basic blood-splatter seminar held each May in Corning, New York, forensic students and law enforcement officers vie for places as if they were front-row tickets for the Superbowl. MacDonell is acknowledged as the world's foremost authority on blood-pattern analysis and somewhat of a showman. His classes are highly theatrical but practical affairs in which the students are encouraged to dip their hands and various lethal implements in buckets of AB negative (supplied by the Red Cross) and imitate beating invisible subjects to death so as to capture the distinctive spray pattern on sheets of white card.

Professor MacDonell is a firm believer in learning from personal experience and there is nothing like creating your own crime scene to hammer home the specifics of blood-splatter science so you will remember it when you see a similar pattern on site. On one memorable occasion a volunteer was required to take a mouthful of warm blood and spray it onto a plain backdrop to simulate the pattern made by the last gasp of someone who had been shot. To the untrained eye blood sprayed on the shirt of someone attempting to help a gunshot suicide would be almost identical to that found on the shirt of a shooter who was up close to their victim, so the distinction is crucial.

Over the course of 14 key experiments the students learn everything there is to know about how blood behaves when it gushes from the human body by measuring its velocity, density and distribution. At the end of the week they will be able to look at dried droplets on a white card and say whether the victim was standing up, sitting, lying down or moving when struck, by what implement and from which direction. They will also be able to tell whether the victim was dragged or crawled to where they were found and if bloody footprints indicate whether the assailant was walking or running from the scene. All of this could be vital in establishing the perpetrator's state of mind at the time of the attack.

Mass production and global distribution has ensured that millions of people now wear the same brand of footwear and drive vehicles of an identical make and model, factors that have significantly degraded the value of shoe prints and tyre tracks in criminal investigations.

Casts made from plaster of paris can help identify shoe prints and tyre tracks

Unless a shoe or tyre has a unique manufacturing flaw, features distinctive wear or carries trace evidence from the scene, its only value as evidence is likely to be circumstantial. Nevertheless, in an investigation every item of evidence is considered significant and treated as crucial to the case.

Even if the print is from a common brand of shoe with no distinguishing features, it can still be of help in building a profile of the perpetrator. Shoe size is roughly proportionate to physique; a small, narrow print would indicate a person of small build. And if investigators are lucky, the depth of the impression may reveal a specific physical characteristic such as a limp which could help narrow down the number of suspects, or the fact that the individual was carrying something heavy to the location where a body was found and returning with a lighter step, having been relieved of their burden.

Footprints found at the scene are routinely photographed using flash lighting to emphasize the depth of the tread with a measuring rule placed alongside the print so that a full-size enlargement can be used for comparison with shoes belonging to the suspect. The pattern made can then be copied onto clear acetate and overlaid onto the sole to see if there is a positive match. Impressions left in dust, dirt, fine soil or powder can be lifted like fingerprints with an adhesive gelatine on a fabric backing or with electrostatic foil. Alternatively, a cast may be taken.

To secure a cast the print is fixed with a hardening agent before the plaster or dental wax is poured in, after which it can then be scanned into the lab's computer, enhanced to reveal characteristic features and finally cross-checked against a footwear database to see if there might be a match to prints found at other crime scenes. Footwear databases such as SICAR are periodically updated by the manufacturers, who supply images of their new patterns because they readily acknowledge the value of the database to the law-enforcement authorities.

Tyre prints are photographed, fixed, lifted and identified in the same way. Once investigators have a cast or photographic enlargement they can identify the tread pattern using a standard industry reference guide that will provide the name of the manufacturer and even the factory where the tyre is made.

INDIVIDUALLY UNIQUE

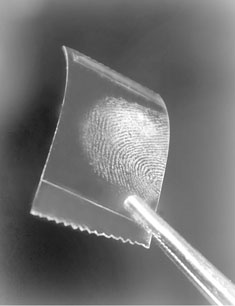

Fingerprint analysis relies on the fact that every individual possesses a unique pattern of whorls, loops and arches on each finger which remain unaltered throughout our life and that each finger carries a minute residue of sweat to which dust and other microscopic matter adheres which is then transferred to whatever we touch. Although invisible to the naked eye these patterns can be highlighted by dusting with fingerprint powder, or fuming with compounds such as ninhydrin or Super Glue which enables them to be 'lifted' on to adhesive film for analysis back at a crime lab. These are known as 'latent prints'. Prints left in blood or paint, for example, are able to be seen and are therefore known as 'visible prints', while prints that leave an impression in a pliable medium such as clay or food are classified as 'plastic prints'.

Prints can be taken from almost any surface, although the age of the print and the nature of the surface will determine whether it can be lifted at the scene or if the object needs to be removed to the lab, provided, of course, that it is portable. At the lab it will be placed in a vacuum metal deposition chamber which is filled with metallic vapour (first gold and then zinc) which adheres to the fatty deposits excreted from the finger.

For porous surfaces such as paper, standard fingerprint powder is of little use because the material will have absorbed most of the fatty residue from the fingers, so magnetic bristleless brushes are often used to powder the print with a fine dust of iron filings. Once the excess is blown away the pattern becomes visible and can then be lifted and photographed. Alternatively, chemical reagents can be used which change colour when in contact with sweat.

Today we are used to hearing of multi-million dollar heists such as the 1983 Brinks Mat Bullion Robbery at London's Heathrow Airport which netted £26 million in gold bullion and the recent £26.5 million Northern Bank raid when the finger of suspicion was pointed at the IRA. By contrast, the £2.3 million haul from the Great Train Robbery of 1963 might not seem so impressive (especially when it had to be shared among a large gang), but it was the sheer audacity of their exploit which caught the public imagination.

Nothing like it had been attempted in Britain before and, to add spice to the proceedings, some of the gang managed to escape to more exotic locales from where they thumbed their noses at the authorities who appeared powerless to extradite them.

But although they liked to think of themselves as lovable rogues, they were neither sophisticated nor smart. During the course of the robbery they had hit the driver over the head so severely that he was traumatised for the rest of his life. And when they fled from their safe house in Oxfordshire as the police closed in they hadn't the sense to wipe their fingerprints from the cups they had been using or from the playing pieces in the monopoly game which they had been playing with real money to while away the days spent in hiding.

Their prints on the bank notes used in the game linked them to the cash that had been taken from the train which wrapped up the case against them and ensured that the gang did not pass 'Go' but went directly to jail.

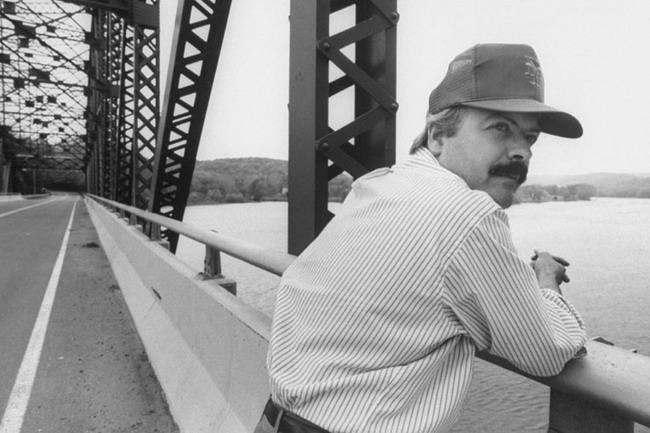

Bruce Richard Reynolds, the last of the great train robbers to be captured, arrives for a brief court appearance in 1968

Of course, investigators will only be able to come up with a match if the perpetrator's prints are in the national AFIS database (automated fingerprint identification systems) as the result of an earlier conviction, but in the US alone there are several hundred million prints on file and as many of these are career criminals who are likely to reoffend, the chance of obtaining a positive match is very high.

It takes the computer less than a second to evaluate a suspect's prints against a half million in the database by scanning the geometric pattern and comparing ten key points in the whorls, loops and ridges. But even when a match is made the technician must determine whether it is valid or not. He or she will be looking at four signature features: arches, which, as the term implies, are formed by ridges running from one side to the other with an arc in the centre; tented arches, which have a sharp point and are rare, seen in only about 5 per cent of the population; whorls, which take their name from an elliptical spiral pattern that evolves from a central point like a spring that has been pulled out of shape; and loops, which have a gentler curve than an arch, with the ends converging. Radial loops lean toward the thumb with ulnar loops slanting to the opposite side. For this reason it is crucial to record from which hand the print was taken.

Some people have what are known as 'accidentals' which create an irregular pattern. More rarely found are people whose prints are a mixture of two patterns which categorize these prints as 'composites'.

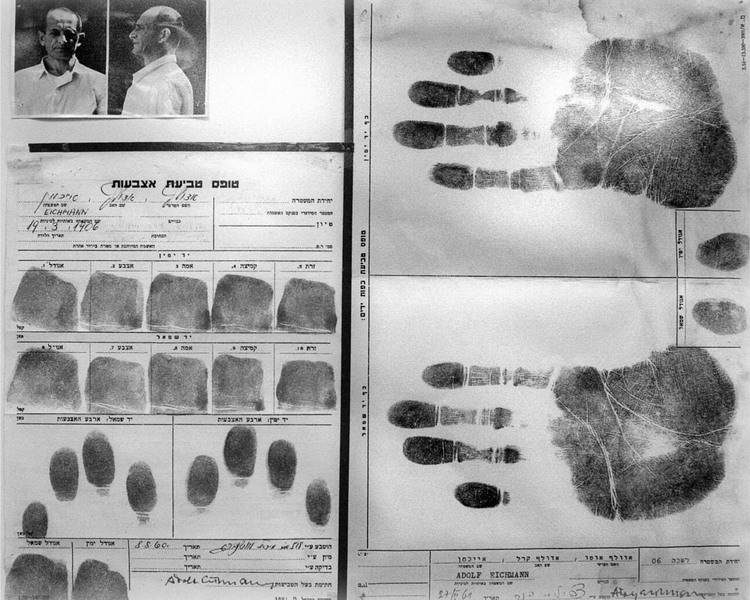

A reproduction of an Israeli police file showing the fingerprints of Nazi war criminal, Adolf Eichmann

Even in these days of routine DNA analysis fingerprinting remains a vital element of crime detection. The real value of fingerprint evidence, aside from its ease of use, is that it is universally accepted by juries who know they can rely on such evidence to place a defendant at the scene of a crime.

FINGERPRINTS

In 1823 Professor Johannes Purkinje, a Prussian, classified fingerprints into the nine basic types and in doing so laid the foundation of modern forensic science. Prior to this convicted criminals were identified by their body measurements according to a system devised by a French medical student, Louis-Adolphe Bertillon, which was both impractical and inconsistent. In fact, it was only by chance after a pair of black convicts with the same name and body measurements were found to have different fingerprints during an investigation in the US in 1903 that fingerprinting was finally accepted as a more reliable form of identification.

The two convicts looked like identical twins and only the papillary lines in their fingerprints could distinguish between them. If fate or chance had not brought them together in the same prison at the same time the case for fingerprinting might never have been proven.

It is said that criminals unconsciously harbour a desire to be caught in order to unburden themselves of guilt. While that may be true of those killers with a conscience who have murdered in a fit of passion and are later haunted by remorse, it is certainly not applicable to the career criminal, rapist, terrorist or serial killer who will all go to great lengths to cover their tracks. A professional burglar wears gloves as a matter of routine, serial rapists often mutilate their victims in an attempt to destroy DNA evidence, and cold-blooded killers who are wise to the value of forensic evidence may try to dispose of their victims by fire, burial or dismemberment rather than risk discovery. But even the most calculating and meticulous criminal can be traced and unmasked by the marks left by the tools of their trade. Every implement leaves its marks and so can be matched to the material it was applied to, whether these are chisel indentations on a wooden windowframe, plier striations on bomb-making components or the marks of hatchet teeth on human bone.

Although mass-produced tools may be identical when they leave the factory, they inevitably acquire unique gashes, scoring and irregularities through repeated use. And though toolmarks can be as distinctive as fingerprints they need to be found and preserved immediately after the crime has been committed, otherwise they may lose their value as evidence since the incriminating marks will be eradicated by further use.

Photographic evidence is often not sufficiently reliable to provide a positive match so either the object bearing the toolmark will be brought in to the lab for comparison or a cast will be made using forensic resin. In either case a comparison can then be made by using the suspect's tool on identical material and studying the striations on the original object with that of the lab sample, in a similar technique to that used in ballistics when comparing rifling markings on bullets and shell casings.

However, identifying characteristic patterns may not be enough to connect the suspect to the scene, so the next stage is to subject the implement to further microscopic analysis for trace evidence which may have adhered to the blades or parts of the tool which will have come into contact with material at the crime scene.

In 1905 the practical value of fingerprinting, or dactyloscopy to give the technique its scientific name, had yet to be proven in a British court. Then on 27 March that year Scotland Yard's leading detective, Melville Macnaghten, was summoned to the site of a double murder which promised to provide the proof the police had been waiting for.

When Macnaghten arrived at the scene in a small paint shop in the London suburb of Deptford he found the body of the elderly owner in a pool of blood on the ground floor amid the debris of a violent robbery and his wife bludgeoned to death in an upstairs bedroom. The only witness was a milkman who had caught a fleeting glimpse of two men fleeing the scene. The taller man was dressed in a blue serge suit and bowler hat, while his companion sported a dark brown suit, cap and brown boots.

Fortunately, there were a couple of potentially significant clues: two home-made hoods which the murderers had discarded and a single smudged fingerprint on a cash box found under the old woman's bed. But during his questioning of the officers at the scene Macnaghten learnt that one of the constables had pushed the box out of the way when the stretcher-bearers came to remove the old woman's body. So he sent the box to the Yard's rudimentary laboratory for examination and ordered the officer to have his fingerprints taken along with the old man's apprentice and the victims themselves.

FINDING SOME SUSPECTS

The next morning Macnaghten was informed that the laboratory had been able to lift a clear thumbprint from the box and that it did not match the prints taken from the police officer, the apprentice or the victims. A laborious manual search of the 80,000 prints stored on cards in the Yard's fingerprint files also drew a blank. But Macnaghten was confident that all he had to do was apprehend all likely suspects and obtain a sample print for comparison.

In those early days of forensic detection many common villains were not as circumspect as they are today and openly bragged of their crimes in the mistaken belief that only an eye witness could convict them. With that in mind, Macnaghten dispatched detectives to Deptford's drinking dens to mix with the locals and listen for any mention of likely candidates for the killings. By closing time he had the names of brothers Albert and Alfred Stratton.

When questioned, Albert's landlady revealed that she had found black stocking masks under her lodger's mattress, while Alfred's mistress, Hannah Cromarty, offered to inform on him if the police would promise to lock him up as she was in fear of her life from his continual physical abuse. Hannah confided to the police that Alfred had left her room through the window on the morning of the murder to avoid the risk of being seen by the other lodgers and that he had made her swear to lie about his whereabouts if she were to be questioned. She told the detectives that he had also disposed of his brown overcoat that day and dyed his brown shoes black.

That was enough to have the brothers arrested and brought before a magistrate who would decide if they should be held in custody while the case was made against them. Fortunately for Macnaghten, the magistrate was curious to test the reliability of the new technique. He ordered the brothers to be held for a week and their fingerprints taken for comparison with the sample obtained from the cashbox. It proved to be crucial, as neither the milkman nor Alfred's mistress were able or willing to testify in court.

The science of fingerprinting was so new that neither the judge nor the jury had even heard of it. Macnaghten would have to prove that it was reliable or risk losing the case. Scotland Yard's resident fingerprint expert, Chief Inspector Collins, made a compelling presentation using photographic enlargements and blackboard sketches to illustrate the indisputable similarities between the thumbprint lifted from the cashbox and that obtained from Alfred Stratton.

The defence team, who were clearly unfamiliar with the technique they were attempting to denigrate, attempted to plant doubts in the minds of the jury by pointing out minor discrepancies which Inspector Collins was able to explain as the insignificant imperfections caused by having to roll the inky thumb over the card. To prove his point he invited each member of the jury to have their thumbprints taken and, having done so, pointed to the same discrepancies in their prints. The fate of the Stratton brothers appeared to be sealed.

DISHONEST EXPERTS

But then the defence offered the testimony of two key experts who were prepared to prove the invalidity of fingerprinting as a forensic science, one of whom was an advocate of the rival system of Bertillonage and the other Dr Henry Faulds, the man who for many years had claimed sole credit for inventing the technique of fingerprinting!

Under cross-examination Dr Faulds was exposed as a petty and vindictive man whose bitterness towards those who had adopted and developed his technique was so intense that he was prepared to renounce his own discovery out of pure spite. During questioning by his own lawyer Dr Faulds became so agitated at having to justify his validity as an expert witness that he lapsed into a sulk on the stand and refused to cooperate any further.

The final offensive against the adoption of the new technique came when Dr Garson, a once-enthusiastic advocate of the now discredited system of Bertillonage, took the stand. Dr Garson had in fact developed his own fingerprinting method as soon as he saw that Bertillonage was losing credibility, but when he realized that his own system was imperfect he covered his failings by blaming the theory rather than his inadequate application of it.

As the public gallery fell into a hushed expectant silence Prosecutor Richard Muir approached the man who appeared to be the last dissenter against the new science, brandishing a letter which he held aloft for all to see. Had Dr Garson written this letter, he asked, and in it had he not offered his services as an expert witness on the validity of fingerprinting to the prosecution? Had his offer been accepted would he now be testifying on oath as to the value of fingerprinting instead of denying it?

Dr Garson blustered and prevaricated but was cut short by the judge, who condemned him as an untrustworthy witness and ordered him to step down.

The case against the Stratton brothers and in favour of fingerprinting had been proven beyond reasonable doubt. The brothers were hanged and fingerprinting was soon being adopted throughout Europe and ultimately in every country in the world.

Even today after the discovery of DNA profiling, fingerprinting remains the single most reliable technique in forensic detection.

Occasionally the police are so keen to secure a conviction that they overlook the evidence – or lack of it, as in the case of Susie Mowbray, a Texan housewife, who faced life imprisonment for allegedly shooting her husband Bill to death while he lay in bed. Described by friends as a 'generous man', Bill was given to dramatic mood swings, compulsive spending and, at the time of his death, was up to his eyes in debt.

Bill Mowbray was a wealthy Cadillac dealer in Brownsville Texas. He died from a single gunshot wound while lying in bed and his wife Susie, who had been lying next to him, was swiftly accused of his murder. Professor Herbert MacDonell, an expert on human bloodstain evidence, was asked to examine the physical evidence for the prosecution.

The professor concluded that Susie would have had blood on her nightgown if she had fired the fatal shot, which had been from such close range that it had left a distinctive star-shape rupture in her husband's temple. There was back splatter on the headboard and the sheets, but stereomicroscopic examination of the white long-sleeved nightgown revealed no trace of blood. Susie simply would not have had time to change her nightgown before her daughter came running into the room only a few seconds after hearing the shot.

Professor Herbert MacDonell, regarded as the world's leading expert on bloodstains

This lack of evidence however did not deter the local prosecutors who insisted on proceeding with the trial and even enlisted the assistance of a second 'expert witness' who sprayed the garment with luminol and claimed it revealed invisible blood spots. MacDonell's report was suppressed by the prosecution and Susie was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment.

An appeals attorney working with Susie's son, Wade, got in touch with the professor six and a half years later. As MacDonnell had been convinced that the Bill's death was suicide and that the prosecution had buried his report about the evidence, he was happy to give his services for free. It was only on appeal that MacDonell was asked to testify and the original expert was discredited, which resulted in Susie's acquittal. But by then she had spent nine years in prison for a crime she did not commit.

The professor examining the evidence

Susie Mowbray: freed after nine years in prison

Abduction is a traumatic experience. Kidnap victims who survive their ordeal rarely remember anything of value to detectives, but Oklahoma millionaire Charles Urschel proved to be a shrewd observer with a keener eye for forensic detail than most FBI recruits.

On a warm summer evening in 1933 Urschel was abducted from his front porch at gunpoint by two armed members of a gang led by Public Enemy Number One, Machine Gun Kelly. Fortunately for Urschel, Kelly was not the smartest gangster of the prohibition era. He hadn't even thought of looking up a photograph of his intended victim in a local newspaper. So when he and his accomplice surprised two elderly men at Urschel's home that night they had to drag both of them into their car as neither would identify which of them was the billionaire. Later, having rifled through their wallets, the gang tossed Urschel's friend from the car and sped off down the dirt road to their hideout across the state line.

Kidnapping was a federal offence and so experts from the FBI were swiftly on the scene, but even they had to admit that the chance of locating the gang's hideout in such a vast landscape was like finding a needle in a haystack. They advised Urschel's distraught wife to wait it out. Before long a ransom note was received demanding $200,000 in cash and this was accompanied by a letter in Urschel's handwriting proving that the demand was genuine and that he was still alive.

TAKING IT ALL IN

Urschel was not only alive, he was more actively involved in his own rescue than the FBI agents. Though blindfolded and bound, he made a mental note of every detail of his lengthy and uncomfortable drive through the night which might prove to be of use, if and when he was finally released. From the sound of the engine and the feel of the seats he identified the car as either a Buick or a Cadillac. That in itself would have been of little use, but when they later pulled in for gas he overheard one of the gang making conversation with the female pump attendant about local farming conditions and recalled her commenting that the crops thereabouts were 'all burned up'.

Prisoner in chains: a member of the gang who kidnapped Charles Urschel is captured

At the next stop he noted that one of the gang mentioned the time, 2.30pm. When they arrived at their destination Urschel was kept blindfolded, but he listened out for any sounds that might give away his location. It was clear from the barnyard noises that he was being kept on a farm and that it had a well with a creaking windlass.

More significantly, the water drawn from that well had a strong metallic taste from the high concentration of minerals. Kelly hadn't thought of removing his victim's wristwatch so Urschel was able to make a mental record of the time an aeroplane passed overhead, twice daily except on Sunday when a rainstorm presumably forced it to divert from its usual route.

By the time the ransom was paid and plans were being made to return him to his family, Urschel had managed to leave his fingerprints on everything he could touch. And thanks to the details Urschel had supplied, the FBI were able to identify both the aeroplane and the drought-affected area which it had avoided on that Sunday morning due to the storm. They contacted every airline that operated within a 600-mile radius of Oklahoma City and cross-checked schedules and flight plans until they had identified the flight that Urschel had noted. They pinpointed the farms the plane would have passed over at that time of the morning and again in the evening, which considerably reduced the number of haystacks they would now have to comb to find their needle. At the Shannon ranch they struck lucky. They not only found a member of the gang with his share of the ransom money, they also made a connection with the Kelly gang. They learned that Mr and Mrs Shannon's daughter Kathryn had married Kelly and even given him his nickname in the hope that the ham-fisted hoodlum who had never fired a gun in anger would be worthy of his reputation.

When Urschel was brought to the farm he immediately identified it as the place where he had been held. Even the water tasted as he had remembered. But most damning was the fine collection of his fingerprints over every surface he could reach which placed him at the scene, one of the few cases in which the victim's prints proved more significant than those of the criminals. Kelly was incarcerated in Leavenworth, where he died in 1954.

Law enforcement: Homer S. Cummings and J. Edgar Hoover plot the trail of the Kelly gang across state borders

On the night of 26 September 2002 a fierce storm was raging through Front Royal, Virginia, making driving hazardous in this bleak rural district of Massachusetts. One driver returning home late slowed as he came to the flooded, aptly named Low Water Bridge and caught sight of something curious in his headlights. It was a vehicle with a man slumped at the wheel and another gravely wounded in the passenger seat. Both had been shot at close range. The passenger, 20-year-old Joe Kowaleski, was rushed to hospital where he remained in a coma for days, unable to give detectives the vital clues they needed if they were to catch the killer. His friend, Ty Lathon, was pronounced dead at the scene.

When Kowaleski recovered he couldn't remember anything other than a glimpse of a red jeep approaching at speed followed by a blinding flash. More bad luck came with the realization that the rain had washed away all clues. All that remained were two empty 12-gauge shotgun shell casings and a set of skidmarks from a vehicle that had evidently pulled up alongside just long enough to allow a gunman to empty both barrels into the victims. However, it was impossible to take prints from the tyre tracks because they were on gravel. Both the weather and the environment were conspiring to keep the killer's identity a secret, but the motive at least was clear. There was an assortment of drug paraphernalia in the victim's vehicle and three cellphones, two of which belonged to the victims, the other owned by Lathon's ex-girlfriend Julie Grubbs.

Grubbs didn't own a red jeep, but her new boyfriend did. His name was Lewis Felts and he was a known drug dealer. Investigators staked out his home and arrested him when he appeared with a box of cleaning products looking intent on eliminating the remaining clues. They confiscated the vehicle and searched the apartment, where they found a significant quantity of drugs, $1,200 in cash together with a fourth cellphone.

Felts and Grubbs denied being at the scene, claiming to have stayed that night in Grubbs' apartment, 96km (60 miles) from the crime scene. But subsequent enquiries revealed that Grubbs had used the fourth phone to call Ty Lathon 22 times on the night of the murder and that her calls had been logged as being relayed from several towers along Route 50 as she had driven south. The final call was traced to Front Royal.

Although the cellphone records destroyed the couple's alibi they did not prove they had committed the murder or that they were at the murder scene, only in the vicinity. It was conceivable they might have been lying to avoid incriminating themselves in drug dealing.

THE FORENSIC PROOF

The detectives then called in a forensic geologist to examine dried mud found in the jeep's wheel wells. He sieved it to separate the coarser soil from the finer material and then subjected both to microscopic analysis. What he found sealed the guilt of the killer couple. In the samples of dried mud were fragments of sparkling blue azurite and emerald green malachite, copper-based minerals which had been washed downstream from a working quarry to Low Water Bridge. This discovery placed the jeep at the scene and all that remained was to place the weapon in Felts' hands. A friend of Felts came forward to tell how he had sold Felts a shotgun three weeks before the shooting. Better still, he had kept a couple of shells. These were shown to match those discarded at the scene. At the end of his trial Felts was found guilty of capital murder and attempted murder and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Sometimes weather and environment conspire to protect the killer

What had appeared to be a drugs hit turned out to be an old-fashioned crime of passion. Lewis Felts had killed Ty Lathon over a girl.

Forensic science is not simply a matter of running trace evidence through high-tech apparatus and printing out the perpetrator's ID after the database has produced a match. Even the most sophisticated equipment can only analyze the evidence. It takes a tenacious, imaginative and highly motivated CSI to gather all the elements, interpret the evidence and make a case. The following account is a good example of the lengths that forensic scientists must now go to and the attention to detail they need to secure a conviction.

Just before Christmas 1986, the police received a call from Keith Mayo a private investigator, who said he was concerned that his client, flight attendant Helle Crafts, had gone missing from her home in Connecticut. When questioned, her husband Richard claimed that she had stormed out after an argument and that he had no idea of her whereabouts. Neither had her colleagues, but without a body there was nothing much the police could do except conduct a routine missing persons enquiry. Until, that is, a snowplough driver remembered seeing a man fitting Richard Crafts' description operating a wood chipping machine by a river at 3.30am in the midst of a blizzard. The inference was clear. Crafts had dismembered his wife's body and shredded it into compost. If he had tipped the contents into the river the current would have distributed the remains across the state and no amount of circumstantial evidence would be enough to convict him.

Fortunately the coroner in charge of the case, Henry C. Lee, possessed local knowledge and told the police precisely which spot on the river to search as body parts had been washed up there in earlier cases. Sure enough, they pulled a chain saw from the water and were able to match it to the chipper and the truck that Crafts had rented. But even this proved only that Craft had discarded a rented saw in a river. It did not prove conclusively that he had mulched his wife's remains.

An observant snowplough driver's actions helped convict Helle Craft's killer

A GRUESOME TASK

So for nearly a month investigators scoured the first location where Craft had been seen using the shredder during the snow storm and were able to bring back a small mountain of wood chippings and what appeared to be human tissue to Lee's laboratory. There the team sifted through the debris, putting plant material to one side and human hair, tooth fragments and tissue in another.

Each hair had to be analyzed to see if it was animal or human and, if it was human, which race and gender it belonged to. Hair that had been pulled had to be separated from hair that had been shed naturally and then those that had been torn out had to be matched to a specific part of the body. Hair that had been cut had to be subjected to further examination to see if it had been cut cleanly by scissors or ragged by a shredder. After separating body fragments from the wood chippings, Lee and his team were left with just a few ounces of body parts, a fingernail, a dental crown, a bone fragment and pieces of plastic bag in which the body parts had been transported to the site.

Flight attendant Helle Crafts who went missing in 1986

Tooth fragments proved sufficient to positively identify the rest of the remains as belonging to the missing woman and when Dr Lee identified a bone fragment as part of the skull it proved conclusively that Mrs Crafts was dead. Moreover, the tissue on the chainsaw matched tissue found at the site; hair taken from Mrs Crafts' hairbrush was matched with hair recovered from the chippings and, if that wasn't enough, a sliver of nail polish was analyzed with a sample obtained from a bottle at the Crafts' house and found to be identical.

But the final flourish in Henry Lee's exemplary investigation was his decision to consult R. Bruce Hoadley, a forensic tree expert. By examining the chippings found at the river and those taken from the hire truck, Hoadley was able to state that they were from the same tree and that both chippings showed the distinctive cut marks made by the chipper that Crafts had hired.

If Richard Crafts had entertained hopes of evading arrest and prosecution for murder, he had seriously underestimated the dedication and dogged persistence of the forensic investigators on his case, who had spent almost three years putting their evidence together. When his case came to trial in 1989, Richard Crafts' defence was systematically demolished by Dr Lee and his team of expert witnesses. Crafts was found guilty and sentenced to 50 years in prison.

Private investigator Keith Mayo was hired by Helle Crafts before she disappeared when she discovered that her husband had had a series of extra-marital affairs

When Leslie Harley, an elderly woman's nurse and companion, was put on trial for the attempted murder of widow Ellen Anderson in 1973, Harley's defence counsel claimed that the old woman's injuries were sustained during an accidental fall and that blood splatter on the ceiling was the result of Anderson shaking her head violently in response to her carer's questions and not of a frenzied attack with a poker as the widow had alleged.

But the defence underestimated the thorough and somewhat eccentric Professor MacDonell, who argued that even the most violent shaking of the head could not account for the spray pattern found on the ceiling of the old woman's bedroom. Even if the old woman had been able to shake her blood-soaked hair so violently that it sprayed onto the ceiling, it would have left a criss-cross pattern and not the perpendicular pattern found at the crime scene. When Harley's counsel came to cross-examine MacDonell he leaned intimidatingly close to the witness and sneered, 'Come now, professor, you have no basis for that opinion, have you? You certainly have never conducted experiments with a live subject whose hair was wet with blood to see how far they could shake it, have you?'

To the astonishment of the advocate and the court, Professor MacDonell proudly admitted that he had done just that only a few weeks earlier. Knowing that he would be called as an expert witness, MacDonell had replicated the incident by soaking a female volunteer's hair in human blood (an out-of-date batch obtained from the Red Cross) and had her lie on a table which was the same distance from the ceiling as the widow's bed had been. He then instructed her to shake her head violently from side to side and videotaped the results. As the professor had predicted, no blood reached the ceiling. But when MacDonell beat the pillow the volunteer had been lying on with a broom handle dipped in blood to replicate the poker he left the characteristic criss-cross spray pattern on the laboratory ceiling that the police had found above the bed at the crime scene. The video of the experiment was offered as evidence and Leslie Harley was subsequently found guilty and sent to prison.