The skull has characteristics that vary between the sexes

Not all murderers leave behind a fresh corpse that can be readily identified and examined for clues. Some dismember their victims in a desperate attempt to make identification impossible or bury the body where it will lie undiscovered for months or even years. Sometimes there is little more to go on than a fragment of bone. But no matter how decomposed a body might be when it is finally uncovered, or how little there is left to identify, the forensic anthropologist, with his expert knowledge of the human skeleton, has the skills to determine the manner of their death and lead investigators to the person or persons responsible.

The skull has characteristics that vary between the sexes

Even in these days of high-tech forensic science many killers still believe that if they can dismember, burn or severely degrade their victim's corpse they will render it unidentifiable and increase their chances of literally getting away with murder. But even skull fragments or a single bone can be enough to identify a body and determine the manner of death. No matter how badly decomposed, charred or fragmented a corpse may be, it is still possible for an experienced forensic anthropologist to determine the age, gender, physical build and ethnic origin from a few key features of the skull and skeleton.

Ethnicity can be determined by examining the shape of the skull. Caucasians have long, broad skulls with receding jawlines and comparatively flat cheekbones; the typical Asian skull is flatter, elongated and distinguished by the prominent cheekbones, oval eye sockets and the fact that the bridge of the nose is lower than that of a white person. In contrast, the shape of the African skull is narrow with wider nostrils and larger teeth.

The width of the pelvis and the shape of the sacrum (the fused vertebrae at the base of the spine) are the best indicators as to whether the victim was male or female, both being narrower in males. But the skull also has characteristic features which vary between the sexes. A bone at the back of the skull known as the occiput and a bone beneath the ear are both more pronounced in men, as is the ridge above the eye socket. In cases where only a few bone fragments are recovered it is still possible to determine gender from the thickness of the bone. Male bones tend to have larger ends to support their stronger muscles.

INFORMATION FROM THE SKELETON

By examining the size and density of specific bones a forensic anthropologist can determine the stage of skeletal development, which is a reliable indicator of age. The skeleton of a child is quite distinct from that of an adult not only in size and density, but also in the amount of cartilage at the joints linking the individual bones.

Conversely, if the skeleton shows signs of degeneration, then it is almost certainly the remains of an elderly individual.

If the skeleton can be reassembled the height and build of the person can easily be determined, otherwise individual bones can provide a clue to their stature and physique. The length of the femur (thigh bone), for example, is a reliable indicator of height. To determine a person's height from their thigh bone all the anthropologist has to do is multiply its length by three.

Further clues to the individual's identity can be found by examining the condition of the bones, which can betray their medical history, the means by which they met their death and even their occupation. Blows from a blunt instrument will shatter bones, producing tiny splintered shards, bullets will leave characteristic holes and sharp-edged weapons can chip and score the bone. Previous injuries such as fractures leave recognizable scars, while severe disability, chronic illness, arthritis and even occupational wear and tear can leave their mark on the skeleton, providing more clues.

A leg bone is washed after being collected from a mass grave

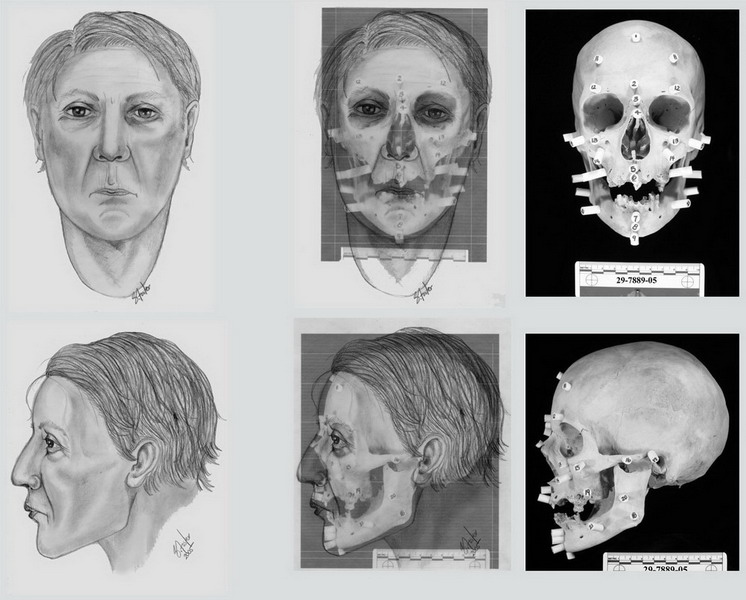

When a corpse is discovered in an advanced state of decomposition and there are no clues to its identity, the only hope of putting a name to it is to reconstruct the face feature by feature, either with clay applied to the actual skull of the victim, or by generating a three-dimensional computer image. When investigators have an accurate likeness they can then circulate it in the hope that a friend or family member will finally be able to say who it was.

Unlike forensic artists, forensic sculptors do not have the benefit of a witness description, but instead are guided by the fact that although each human face is unique, variations in the shape of the skull determines our characteristics and these can be reconstructed using a system known as morphometrics. This technique, also known as the American method, identifies between 20 and 35 anatomical landmarks where the depth of tissue can be predicted with a high degree of accuracy. The only variations which the sculptor needs to be aware of are those relating to age, gender and ethnicity. They may even manage to get the hair style and colour correct if hairs were found on the body. But they have to use their imagination when it comes to the general facial shape as they cannot know if the subject was fat or lean unless the rest of the bones were also recovered, since their density can often give a clue as to someone's physical appearance.

Facial reconstruction was developed at the end of the 19th century to help anthropologists visualize the appearance of primitive man from fossil remains, but it wasn't applied to forensic detection until the 1930s. Data regarding tissue density had been acquired from anatomical specimens during dissection, but is now more easily and accurately obtained from living subjects using ultrasound.

SHAPING THE SKULL

If a complete skull is not available it can be reconstructed from fragments cemented together like a three-dimensional puzzle and then a cast can be made to provide the sculptor with a sturdy framework. Pegs of varying lengths are attached at the key points to indicate tissue depth and strips of clay of a suitable thickness are applied according to the height of the pegs. The moistened strips are then smoothed over so that the pegs are just below the surface and the clay is worked to shape the contours of the face.

A forensic artist completes a likeness with information gleaned from the skull using the morphometric method

Next, the features are formed with the proportions and placement conforming to certain anatomical principles such as the fact that the mouth corners usually align with the irises and that the nose is as broad as the space between the corners of the eyes. When the head is finished and glass eyes have been fixed in their sockets a plaster mould can be made, which is then painted in flesh tones and the mouth and eyebrows coloured to bring John or Jane Doe vividly back to life.

In contrast, the morphoscopic method, also known as the Russian method, assembles the face muscle by muscle according to the shape of the skull. Each muscle is formed in clay and then attached to build up the face before a thin 'skin' of wet clay is applied to blend them together.

Practitioners of the American method argue that their approach is more scientific and therefore more reliable, while proponents of the 'rival' system contend that their technique allows for atypical features which do not conform to regulation physiological formulas. Both methods have proven effective in identifying anonymous victims of violent crime, so the debate appears somewhat academic.

Computer-generated facial reconstructions are achieved using a similar method to forensic sculpturing except the modelling is done using a powerful PC program rather than a physical medium such as clay. After the skull has been scanned from every angle the data is compiled to produce a three-dimensional image on to which the 35 landmark pegs are positioned and fine tuned by the programmer. Flesh is then applied using data obtained from scans of living subjects which recorded both the shape of their skull and their contours of their face. This ensures that the computer image will not be flat but will have all the textural features that make each human face unique. The CT (computer tomography) scan must then be 'warped' around the skull and adjusted to ensure a perfect fit in much the same way that a thin latex mask is applied to an actor's face.

A 'colour map' of a living person of the same race, age and gender is used as a tonal reference before eyes are sourced from a database which contains every likely combination of shape and colour. Finally, hair is digitally painted on but kept as straightforward as possible and shadows are added at the programmer's discretion to create a photographic lifelike image that will provide the best chance of recognition.

Forensic art involves more than simply sketching 'identikit' portraits of suspects or missing persons from witness descriptions. A forensic artist may also be called in when law-enforcement agencies require an up-to-date visual of a fugitive who has not been photographed for some time, or who may have changed their appearance. A skilled and imaginative artist may also be required to create post-mortem portraits to aid identification, or to re-create facial features when there is little more than a skull to work with. In such cases they will need to have studied the physiological changes which occur after death and be familiar with the craniofacial patterns associated with ageing.

Although there are dedicated software programs that can generate a suitably aged portrait, these still require a degree of artistic skill to create a realistic, workable likeness and many law-enforcement agencies feel that there is no comparison to a portrait sketched by a talented artist who captures the presence of a person and not just their physical appearance.

The greatest challenge for a forensic artist is to re-create a person they have never met from a badly decomposed corpse or a pile of bones. A certain amount of anatomical training will give them reliable guidelines as to the fullness of the cheeks, the shape of the nose and so on, but the 'art' in being a good forensic artist comes from being able to imagine someone from the clues given by their clothes, wristwatches and rings or the size of their bones and remnants of the muscle attachments.

BUILDING UP A PICTURE

When working on a composite portrait, to give an identikit sketch its official name, the artist must keep in mind that descriptions are highly subjective and their reliability is dependent upon many factors, including the duration of the incident, the distance from the suspect, the point of view, the available light, whether the subject was stationary or moving and at what speed, the time that has been allowed to lapse between the incident and interviewing the witness, and lastly the witnesses' eyesight and memory.

But even the most reliable eyewitness can have been unduly influenced by their emotional involvement in a violent incident. If they were upset they might elaborate or instinctively give a stereotypical description which may unconsciously express a prejudice they may have toward a certain race, class, age or type of individual.

There is some truth in the belief that if you ask five people to describe an individual they have just seen for a few seconds they will give you five different descriptions. The reason is that we tend to focus on a single feature – the eyes, an unusually prominent nose, a jutting jaw and so on. In contrast, a forensic artist focuses on the spatial relationship between the features. In this way they are able to capture the appearance of a suspect from a few unfocused frames recorded by a security camera.

However, forensic artists are sometimes forced to rely on instinct to a greater degree. Karen T. Taylor, a forensic artist in Texas who has contributed to the capture of many predatory paedophiles and killers, 13 of whom ended up on death row, cites a case in which she had to provide the FBI with an update of Virgilio Paz Romero, who was then considered to be one of the world's most wanted men. Paz was a conspirator in the political assassination of the former Chilean ambassador to the United States, Orlando Letelier, in Washington, DC. With only poor-quality photocopies of photos of Paz to work from and the knowledge that he was an exuberant personality, Karen built up a picture of Paz as a self-satisfied larger-than-life character sporting a vibrant red shirt. The updated image was aired on America's Most Wanted, and when Paz was captured by US marshals three days later he was wearing a red shirt.

The computer can be used to build up a digital likeness

It is not the job of the profiler to point a finger at a specific suspect, but to draw up a description of a personality type which the police can then use to single out the most likely suspect from a list of potential perpetrators.

The public perception of profiling, gleaned from popular American TV series such as Profiler and Millennium, is that it involves some form of near-psychic perception. In reality, it requires a mixture of psychological insight, an acute intuitive sense and a great deal of experience.

When a serious crime is committed the police have to decide within days if they will require the assistance of a profiler, since vital clues can be lost as the crime scene becomes contaminated by the weather if it is an exterior location, or disturbed by the investigating team.

Once assigned to the case a profiler will be sent a complete set of crime scene photographs, a detailed drawing of the crime scene showing the position of the body, plus a description of the location and surrounding area as well as some background concerning the lifestyle of the victim.

After studying the details of the crime and familiarizing themselves with the victim, the profiler can then focus on which direction the investigation should take. They will visit the location at the time the crime took place so that they can see for themselves what the perpetrator saw and perhaps pick out an important detail. For example, if it is a residential area and the crime took place when there was a lot of activity in the neighbourhood, it might suggest that the perpetrator was someone who would not be considered out of place, such as a delivery man or perhaps even one of the residents walking his dog.

Profiler, the US TV series: to be a criminal profiler you need intuition, psychological insight and experience

You will not find the murder of Pete Marsh described in accounts of infamous criminal cases nor in the files of Scotland Yard, for Pete Marsh was not the victim's real name, but an appellation given to a small heap of 2,000-year-old remains unearthed by a mechanical peat excavator at Lindow Moss in Cheshire in August 1984. Although both Lindow Man – to give him his official title – and his killer were long since dead, this coldest of cold cases was still of considerable historical interest to both archaeologists and scientists around the world as it was the oldest body ever found in Britain and it was in a remarkable state of preservation.

Incredibly, there were still strips of skin adhering to the bones and even tufts of auburn hair, the remains of sideburns, a moustache and a beard. The face was still largely intact, albeit hideously distorted, although the lower half below the ribs had long since disintegrated. In fact, it was such a significant find that the country's top forensic anthropologists were called in to perform a belated autopsy and determine the cause of death.

After a painstaking excavation the remains were transported to the British Museum, where they were subjected to the intimate scrutiny of modern technology. Terrestrial photogrammetry was employed for the first time on a human body to sketch the contours of the corpse, while his stomach contents were subjected to analysis by an electron spin resonance spectroscopy and an endoscopy examined what was left of his internal organs.

By the time the team wheeled in the X-ray equipment they had concluded that prehistoric Pete had not died of natural causes. He had been in his late twenties when he suffered a series of fatal injuries including a dislocated neck and skull fractures. The team realized they needed a second team of forensic pathologists to interpret the injuries and so they approached Scotland Yard.

A SECOND AUTOPSY

The second autopsy was unusual for a number of reasons. Quite apart from the unique nature of the victim, it was a condition of the British Museum that none of the forensic team should be allowed to touch the body, which had been freeze-dried to preserve it as it was in such a fragile state. So they were forced to examine it using mirrors, magnifying equipment and X-rays.

Their findings surprised everyone and provided details of some pretty gruesome Celtic Iron Age customs that even the archaeological experts had been unaware of. This second autopsy revealed that what was originally thought to have been a necklace was in fact a ligature used to strangle the victim. The tissues of the neck had shrunk during decomposition rather than distending, which meant that the ligature had been pulled tight enough to choke the life out of him. The ligature mark was deeply indented and showed pressure abrasion suggestive of a garrotte. The position of the head wound, which had been sufficiently forceful to drive skull fragments into the brain, indicated that the victim must have been standing or kneeling with his back to his executioner.

The scalp lacerations were V-shaped, indicating two blows from a narrow-bladed, blunt-edged weapon such as an axe. Under a stereoscopic dissecting microscope the edges of the wounds revealed swelling that only occurs while the victim is still alive, so the blows were sufficient to render the victim unconscious without killing him. Fracture lines in the skull indicated a beating with a cudgel once the victim was lying senseless on the ground. An additional wound on the side of the neck was consistent with an attempt to sever the jugular vein with a sharp-edged weapon.

From all the information that had been collated it appeared that 'Pete Marsh' had been a ritual sacrifice, but this was not quite the end of the matter. It was only when the team received the results of the analysis of pollen, parasites and body tissues that the full story of his last hours could be told.

From this they were able to ascertain that Pete, or more properly the Lindow Man, was in fact a Druid prince called Lovernios, sacrificed to appease the gods after a bad harvest and the defeat of Boudicca in AD60. Incredibly, his stomach contents revealed the remains of an unleavened barley cake which meant that forensic experts were then able to date his death to the fire festival of Beltane (May Day).

The Lindow Man: his gruesome death was not uncovered for 2,000 years

Perhaps the most unusual and intriguing case in which forensic techniques have been used to determine the identity of both the living and the dead is that of the last Russian Tsar and the woman who claimed to be his only surviving daughter, Anastasia.

In 1920, just two years after Tsar Nicholas ll and his family mysteriously vanished in the confusion following the October Revolution, a young woman was fished out of a canal in Berlin, supposedly a failed suicide attempt. She appeared to be suffering from amnesia, but recalled just enough of her former life to claim that she was the Tsar's youngest daughter, the sole survivor of the Romanov dynasty. It was a claim she maintained until her death in 1984.

Eight years after her death a team of forensic scientists travelled to the former Soviet Union to identify a pile of charred bones that had been discovered in 1979 by a filmmaker, Gely Ryabov, who had been obsessed with solving the mystery of the missing Romanovs. Ryabov had been forced to keep his discovery a secret until the advent of perestroika for fear that the communist authorities would destroy the evidence, as the Tsar was still a potent symbol for many Russians and the state did not want to risk his remains rivalling those of Lenin as an object of pilgrimage – in this case for anti-communists.

The European forensic team were not concerned with the 'Anastasia' case. Their interest was in putting their combined skills to the ultimate test in solving one of the great mysteries of history. It had been assumed that the Tsar and his family had been summarily executed by their Bolshevik captors in 1918, but the bodies had never been recovered and the case of the woman who claimed to be Anastasia ensured that the question of their fate remained in the public consciousness. It was one of the great cold cases of the 20th century, until the American forensic anthropologist Dr William Maples and his team took a night flight to Siberia in 1992 to examine the skeletonized remains.

THE SKELETONS TELL THEIR TALE

The bones were to be identified by matching the measurements to those in the Romanovs' medical records and by superimposing X-rays of the skulls on family photographs. But the team also had DNA from the recently disinterred body of Tsar Nicholas's brother for comparison and so were able to confirm that one of the Siberian skeletons was indeed that of the murdered Tsar.

The Czar, his wife and their young family aboard one of their yachts in 1907

The skull of Alexandra was readily identified by forensic odontologist Dr Lowell Levine, who had obtained her dental records from Germany, where the Tsarina had periodically returned to visit her family. Historians have argued that if the British royal family, to whom Alexandra was related, had offered a haven to the Romanovs the family might have escaped their fate. Certainly the royal connection proved critical nearly 80 years later when the forensic team managed to obtain blood and hair samples from Prince Philip, a direct descendant of Alexandra's grandmother, Queen Victoria, which proved a positive match when compared to DNA extracted from the remains.

Having identified which bones belonged to which victim, Dr Maples then meticulously rebuilt as much of the bodies as he could and then discovered that two of the victims were missing, Alexis and Anastasia. It is believed that the remains of the two youngest children were left in a nearby mineshaft where all eleven members of the group had originally been taken to be burnt, but the Russians could provide no proof.

Fortunately the body of the Romanovs' physician was not completely skeletonized and provided two bullets from the First World War period, which helped to date the deaths to 1918.

But what of the woman who claimed to be Anastasia? Unfortunately, she had been cremated in 1984, but a tissue sample had been archived in a German hospital where she had once been a patient. DNA was extracted from this sample and compared to that donated by Prince Philip. There was no match.

The woman who claimed to be the Tsar's youngest daughter was, in fact, a Polish peasant by the name of Franzisca Schanzkowska who had been identified back in 1927 by a private investigator, but until the introduction of DNA testing his allegation could not be proved. Following the identification of the Romanov remains, one of her descendants provided a blood sample that proved a positive match to the DNA taken from the tissue sample obtained from the German hospital. Schanzkowska was an impostor, but it is a fact that the remains of the real Anastasia were never recovered.

Franzisca Schanzkowska who claimed to be Anastasia Romanov, the Czar's daughter

When investigators first come upon a crime scene where there are multiple victims, they have to determine the nature of the crime with which they are dealing and identify which victim was the real target since it is possible that the other victims were innocent bystanders. Such was the problem facing FBI profiler Dayle Hinman in the case of the brutal murder of an attractive young couple, Missy and Michael MacIvor.

The MacIvors were discovered dead in their luxury home in the Florida Keys on an August morning in 1991. The initial suspicion was that it was a drug-related killing. Michael was an aircraft mechanic and pilot who had allegedly become mixed up with drug dealers, but thought himself 'bullet-proof', according to a friend. Four years earlier he had been arrested by customs for landing a plane with narcotic residue, but he had not been convicted. More recently he had bought himself a plane that had been impounded during a drug seizure and he was heavily in debt.

His body had been found on the living room floor, his eyes and ears covered with duct tape. His wife's naked body was discovered in the master bedroom at the foot of the bed. She too had been tortured and hog-tied (hands and feet trussed up behind her back in one binding) with a belt and a man's tie, then strangled with a cloth belt from a towelling robe. A ladder had been found propped up against a balcony outside the house and the phone wires had been cut, which indicated a degree of planning.

When FBI profiler Dayle Hinman saw the crime scene photographs she immediately discounted the drug connection. If it had been a drug hit, she reasoned, the killers would have brought their own restraints and weapons. Moreover, they would not have covered Michael's eyes and mouth if they had intended him to witness the torture of his wife or force him to give them information. Another clue lay in the fact that Missy's restraints had been tied and untied several times, indicating that she had been the object of the attack while Michael had been murdered merely because he had been in the way.

There were bruises on the back of his neck indicating that he had been struck repeatedly and once unconscious he was left alone. A metal pole was found nearby that looked a likely murder weapon.

Missy had been repeatedly assaulted and strangled indicating that the killer was a sadistic psychopath who enjoyed dominating and tormenting his victims.

THE SEARCH FOR THE SUSPECT

As no other crime of a similar nature had been reported in the area in recent months, Hinman felt it safe to assume the murder was the killer's first and that he was following the usual pattern in having graduated from burglary to rape and finally to murder. On her recommendation detectives began combing the vicinity for likely suspects, since this type of criminal will begin his career in his own neighbourhood as he knows it well and will have his eye on escape routes should anything go wrong. This is what is known as the 'comfort zone'.

Within days a likely suspect was in their sights. Thomas Overton was a small-time cat burglar who fitted the profile. He specialized in breaking into houses where the owner was present. At the time he was working at a local gas station where Missy was a regular customer. This gave detectives a reason to question him but no right to arrest him. Until, that is, he was caught red-handed breaking into a house in the neighbourhood some months later.

Unfortunately, even a criminal caught in the act of committing a crime is not obliged to give a sample for DNA analysis, and with no hard physical evidence to connect Overton to the MacIvor murders there were no grounds for compelling him to submit to a swab under 'probable cause'.

But then the police had a break. While in custody Overton cut himself shaving and threw the bloody tissue away. It then became the property of the police and could be subjected to analysis. A search of the DNA database proved a positive match to the semen found at the crime scene. This was the kind of hard, irrefutable evidence that can crack a case, as there is a one-in-six-billion chance that it could belong to anyone other than the suspect. But it was not enough to prove beyond doubt that Overton had murdered the MacIvors, only that he had been in the house. The police needed to get Overton to deny that he had ever been in the house, then it would prove he was covering up the fact that he had been there on the night in question.

THE CASE IS CLOSED

The detectives devised a strategy to draw out a confession, based on the psychological profile Hinman had provided. They exploited his vanity by inviting him to the police station as an expert burglar to help clear up a series of unsolved break-ins. Overton was encouraged to believe that he might earn a shorter sentence if he cooperated and so he willingly looked through numerous photographs of houses, some of which he had burgled and some of which had been broken into by his associates. When the photograph of the MacIvor house was placed before him, he claimed he had never been there and so implicated himself in the murder. Had he admitted that he had broken in on the day of the murder a smart lawyer might have been able to argue that some unknown assailant had murdered the MacIvors after Overton had left. And as unlikely as that sounds, it might have sown sufficient doubt to get him a life sentence for sexual assault instead of a death sentence for premeditated first-degree homicide.

Florida Keys: the MacIvors were living here when they were brutually murdered

For almost 16 years New Jersey detective Bernard Tracey was obsessed with finding elusive killer John List, who had murdered his 83-year-old mother, his wife and their three teenage children in December 1971 allegedly to spare them the indignity of his inevitable bankruptcy. It was initially assumed that List had subsequently taken his own life, but after his car was found at New York's JFK Airport and it was discovered that he had withdrawn $2,000 from his mother's account on the day of the killings, a coast-to-coast manhunt was launched in the hope of apprehending him. The search was later extended nationwide and eventually on to Europe and Africa in the belief that List's fluency in German might have enabled him to make a new life abroad.

But the trail ran dry and in desperation Detective Tracey turned to a newly developed forensic computer program which could replicate the effects of ageing. But first Tracey consulted Michigan profiler Dr Richard Walter, who created a psychological profile of the fugitive so that the effects of his lifestyle could be envisaged by the computer.

Dr Walter predicted that List's Lutheran religious beliefs would have prevented him from resorting to plastic surgery and that he would be inclined to a plain 'meat and potatoes' diet. This, together with his distaste for physical exercise, would have resulted in slack jowls and an appearance considerably older than his actual age.

After List's last known photograph was scanned into the computer the image was digitally manipulated to simulate the effects of ageing, poor diet and lack of exercise. A receding grey hair line and pale complexion were complemented by thick-rimmed spectacles which Dr Walter believed List's money-conscious conservative nature would encourage him to wear. Then the digital indentikit was broadcast on an episode of America's Most Wanted, prompting a flood of phone calls including one from a lady who named the man as her ex-neighbour, 'Bob Clark'. Mr Clark was duly questioned and, despite protestations to the contrary, his fingerprints proved beyond a reasonable doubt that he was indeed John List. Twenty years after he slaughtered his family then calmly relocated to Denver, Colorado, to start a new one, John List was sentenced to life imprisonment.

John List who murdered his family to escape debt

During 1993 the 'sunshine state' of Florida was making headlines for all the wrong reasons. It had become a stalking ground for opportunist thieves who considered tourists easy prey. Unfortunately, holidaymakers were not difficult to spot as rental car companies marked each vehicle with a company sticker and the criminals relied on the fact that out-of-state visitors would be unlikely to be willing to return to testify, especially if court proceedings could be deliberately and repeatedly delayed on technicalities dreamt up by a shrewd defence attorney.

Over the course of that summer local muggers had become increasingly audacious and vicious, attacking visitors in broad daylight, relying on shock tactics to traumatize their victims and render them less than reliable witnesses. But one gang chose the wrong victim. Despite the adverse publicity German TV producer Helga Luest had no fears about taking a vacation in Miami with her elderly mother. She had recently wrapped up a special report on the Florida crime wave in which she offered safety advice to would-be travellers so she was confident she could take care of herself.

The holiday was all that she had hoped it would be, but on the morning of their return flight Helga took a wrong turning en route to the airport and mother and daughter soon found themselves in an unfamiliar neighbourhood. While Helga tried to get her bearings, a car drove up, blocking her exit, and two black males leapt out. One shattered the driver's window with a single kick while his partner screamed threats to Helga's elderly mother in the passenger seat. Helga fought back bravely, forcing the pair to abandon the robbery and flee empty-handed, but not before they had inflicted severe injuries on their distraught victims. Helga sustained two cracked vertebrae, a serious head wound and a spiteful bite mark in her arm so deep that it had almost severed a muscle. Doctors later confirmed that had the attack continued it is almost certain Helga would have been left severely disabled.

A CLEVER DETECTIVE

Fortunately she recovered from her injuries and her case was assigned to Miami detective Laura Le Febvre, who had many years' experience investigating sexual assaults. Detective Le Febvre knew the forensic value of a fresh bite mark and had the foresight to arrange for it to be photographed under ultra-violet light which gives a three-dimensional image, making it easier to match to a dental impression taken from a suspect.

It was just as well that Le Febvre insisted on having the photograph taken as there were precious few other clues. The perpetrator who had left the bite mark lost his baseball cap in the struggle but it didn't help detectives because the hair samples inside didn't have a root and so there was no DNA to run through CODIS.

Just as the police began to despair of finding the perpetrators, Detective Le Febvre happened to visit the Miami-Dade Police department on an unrelated matter and overheard a conversation which put her on the trail of a prime suspect, factory worker Stanley Cornet. An officer was discussing the arrest of a suspect who had bitten him in an attempt to escape arrest. To make absolutely sure of a positive ID, Detective Le Febvre put Cornet's photo among 100 others, instead of the usual 10.

When Helga picked his picture out without hesitation Le Febvre organized a warrant for Cornet's dental impression. Knowing the game was up, Cornet protested violently and had to be restrained. Clenching his mouth tightly, he stubbornly refused to cooperate. It was then that forensic odontologist Dr Richard Souviron had an idea: he brought in a lethal-looking device that looked as if it might have played a part in the Spanish Inquisition and placed it on the table before the belligerent suspect, the intimation being that he was ready to use it if Cornet continued to refuse to cooperate. In fact, the contraption was used to prise open the mouths of cadavers during an autopsy. Dr Souviron had no intention of using it on the suspect, but the ruse worked and Dr Souviron secured an impression of Cornet's teeth which proved a perfect match to the bite mark on Helga Luest's arm.

Cornet was sentenced to life in prison, while Luest set up a victim support organization, www.witnessjustice.org, to offer advice to victims of violent crime.

Helga Luest whose vacation in Miami with her elderly mother was cut short by a violent robbery

Miami Beach: scene of many crimes in the 1990s

Serious criminal cases are rarely resolved using just one type of forensic evidence. Frequently investigators will build a case on as many levels as possible to leave little room for error in case one type of evidence is ruled inadmissible for legal reasons or called into question by the defence's expert witnesses. In the case of the abduction and murder of 18-year-old Shari Faye Smith, her killer was caught and convicted using a combination of modern criminal profiling and good old-fashioned physical evidence.

Shari had been abducted in broad daylight and within sight of her home in Columbia, South Carolina, on 31 May 1985 as she stopped to collect post from the mailbox at the end of the driveway. Minutes later her father had found her car as she had left it with the engine running, the driver's door open and her purse on the passenger seat.

The police immediately organized the most extensive manhunt in South Carolina's history, but no trace of Shari was found. Later that day the Smith family received the first in a series of bizarre calls from the kidnapper, who disguised his voice with an electronic device. He proved that it was not a hoax by describing what Shari had been wearing under her clothes, but curiously he never mentioned the subject of a ransom. He appeared to enjoy tormenting the family, who still held out hope of finding Shari alive, and he promised that they would receive a letter the next morning.

The letter duly arrived. It was in Shari's handwriting and had been written on a sheet of lined legal paper headed 'Last Will and Testament'. It didn't give a clue as to her whereabouts, but it suggested she could still be alive. But in a subsequent call some days later her abductor said something which confirmed their worst fears. He said that Shari and he had become 'one soul' and he gave detailed instructions as to where they could find her body. It appeared that he had delayed giving them the location until he no longer had a use for her as a trophy and was certain that the body had decomposed sufficiently to degrade any useful forensic evidence. But there was also another reason – many killers keep the location of their victim's bodies a secret as they get a thrill from revisiting the site and reliving the murder.

A PROFILE IS COMPILED

The FBI Signal Analysis Unit concluded that the kidnapper's voice had been disguised using a Variable Speed Control Device, which suggested that he might have a background in electronics. This prompted the FBI to compile a profile which speculated that the man they were seeking would be in his late twenties or early thirties, single, overweight and unattractive to women. The fact that he indulged in cruel mind games, including calling the family reverse-charge on the day of Shari's funeral and describing in graphic detail how he had killed her, suggested that he was probably separated after an unsuccessful marriage and was likely to have a history of making obscene phone calls, all of which were to be proven correct. Two weeks later the same man abducted nine-year-old Debra May Helnick from outside her parents' mobile home in Richland County, 38km from the Smith residence. Then he phoned the Smiths and told them where the girl's body could be found.

It was about this time that the FBI had a break in the case. They subjected Shari's 'Last Will and Testament' letter to microscopic analysis using an ESTA machine, which detects the slightest impression in paper which would be invisible to the naked eye. It revealed a grocery list and a phone number which had been written on a sheet elsewhere in the pad from the one Shari had used. The phone number led detectives to the home of a middle-aged couple who had been out of the country during the period in which the murders had taken place. But they recognized the profile as an accurate description of their handyman, Larry Gene Bell, who they had allowed to live in their house during their absence.

Larry had aroused the couple's suspicion when he had picked them up from the airport and talked about nothing but the murders, and their suspicions were confirmed when agents played the couple a recording of Larry's final phone call to the Smith family in which he had not bothered to disguise his voice with the electronic device. His DNA was later recovered from the stamp he had licked before posting Shari's 'Last Will' and matched with a sample obtained on his arrest.

In 1996 Larry Gene Bell became the last person to die in the electric chair in the state of South Carolina.

Shari Faye's killer, Larry Gene Bell (left)

In real life, crime detection is rarely as simple as the fictional cases portrayed on TV. Fictional detectives invariably have a single suspect in their sights and have only to prove the case against them, while the dilemma facing real detectives is often to identify a guilty, faceless individual from among a million or more inhabitants of a major city. It is a process of painstaking elimination known as the 'needle in the haystack' method and it hasn't changed significantly in 200 years, only now we have computers to speed up the sifting process.

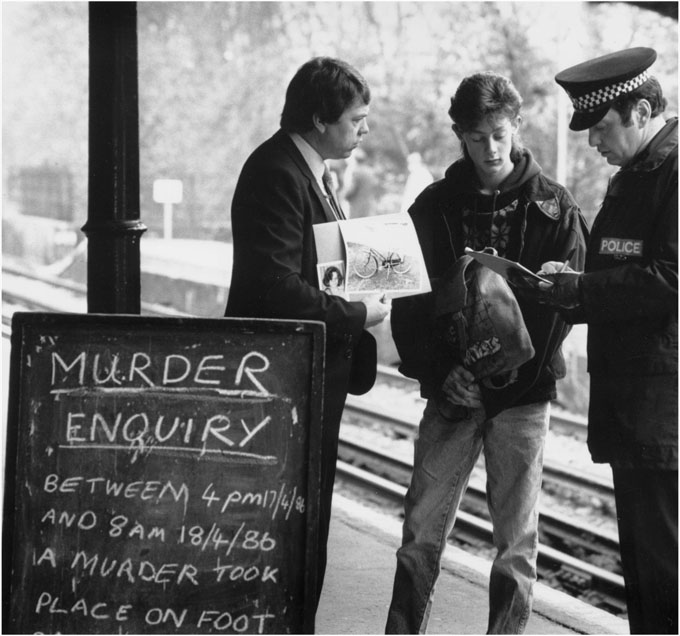

In 1986 the British police were working their way through a list of nearly 5,000 known sex offenders in the hope of catching a brutal serial killer known as the 'Railway Rapist', who had raped 27 women and murdered two more in London and Surrey, all near railway lines.

All the police knew for certain was that he was short, with a pockmarked face and fair hair and that, in the latest case, he had made crude attempts to destroy the evidence of rape by drowning his victim. They also knew that he had attempted to get rid of the evidence in the case of another of his victims by inserting paper into her vagina and setting it alight. Clearly he was a supremely callous and calculating individual.

After the second murder a man answering the vague description was seen running for the 6.07 train from East Horsley to London, prompting a frantic manual search through two million tickets, but no incriminating fingerprints were found.

By this time the police were getting desperate. They had a number of significant clues, including a length of string used to bind the victims' hands, and they had identified the attacker's blood group from semen stains. Analysis of the stains revealed the presence of an uncommon enzyme known as phosphoglucomutase which would eliminate a large number of suspects, but there was no time to interview every man on the list. The killer was likely to strike again at any moment and the police were stretched to breaking point trying to cover all the regional railway stations, which were unmanned by British Rail staff at weekends.

Train travellers were asked if they had seen anything out of the ordinary

WORKING AGAINST THE CLOCK

After Detective Chief Superintendent Vincent McFadden made the decision to pool the resources of all the various investigating teams in the Home Counties, the list was whittled down to a more manageable 2,000 suspects. Each was invited to give a blood sample, but one declined. His name was John Duffy, an ex-railway worker who fitted the description and had a record for rape and assault with a knife. But while the police were debating whether or not to risk arresting him without conclusive evidence he admitted himself to hospital suffering after what he claimed was a mugging, which had also conveniently robbed him of his memory. On his release he raped another woman, but the police still did not automatically link this to Duffy.

At this point in the investigation, McFadden turned to Dr David Canter, a professor of psychology at the University of Surrey, and requested a psychological profile in an attempt to identify the killer. Canter read the case reports and concluded that the so-called 'centre of gravity' connecting these crimes was a 5km (3 mile) area around the Finchley Road in north London and that the killer most likely lived in that neighbourhood. Among a further 16 points Dr Canter highlighted was the likelihood that he would be a semi-skilled worker who had experienced a volatile marriage and now had two close male friends. The data was duly fed into the computer and the name John Duffy was highlighted as a positive match.

A search of Duffy's home unearthed the unusual string used in the attacks and then one of the two friends admitted beating Duffy to give the appearance that he had been mugged so that he could claim to be suffering from amnesia. But the evidence which clinched the case was the discovery of 13 fibres on various items of Duffy's clothes which had come from the sheepskin coat of a victim he had tossed into the river and left to drown.

In the end, the DNA evidence was not decisive; Duffy was jailed for 30 years on the physical evidence and the testimony of three of his surviving victims, and with his conviction the era of this ever-elusive random sex murderer was ended. Since the days of Jack the Ripper sex killers had been notoriously difficult to catch and convict for the simple reason that their behaviour was impulsive and unpredictable. But a combination of computers, psychological profiling and genetic fingerprinting means that sex crimes are now as solvable as other crimes of violence.

Railway Rapist John Duffy was jailed at the Old Bailey in London