Chapter 22

High-Net-Worth Couples

To many Canadians, the Thompsons qualify as a high-net-worth couple on the strength of their $600,000 in investable retirement assets. To investment managers who cater to high-net-worth individuals, the investable amount would need to be significantly greater than that to get them interested in you as a client.

It is time to introduce the Clarkes. Joel and Colleen Clarke have $3 million in investable assets as well as a paid-off house worth over $1 million.

Not all the Clarkes’ $3 million in assets is contained within tax-sheltered vehicles. The dollar limits imposed by the government on tax-deductible contributions make it difficult to accumulate that much wealth in tax-sheltered arrangements unless you’re a high-level civil servant. In the case of the Clarkes, they hold some of their money in non-tax-sheltered assets (NTS assets).

The key components of their holdings are given in Table 22.1.

I will assume that the Clarkes incur four spending shocks between the time Joel is 67 and 78 and that the shocks total $110,000. This is more than what the Thompsons had to endure, but we should expect that the size of shocks will grow in line with one’s net worth. (If the amounts stayed small, they wouldn’t really be shocks.) Given their sizeable financial resources, we will assume that the Clarkes do not bother to set up a reserve fund to cover the spending shocks.

Table 22.1. Data on Joel and Colleen

|

Joel’s and Colleen’s ages |

65 and 62 |

|

Savings in RRIFs |

$2,000,000 |

|

Savings in TFSAs |

$200,000 |

|

Savings that are not tax-sheltered |

$800,000 |

|

Joel’s estimated CPP (as a % of maximum) |

100% |

|

Colleen’s estimated CPP (as a % of maximum) |

75% |

|

Annual investment fees before Enhancement 1 |

1.80% |

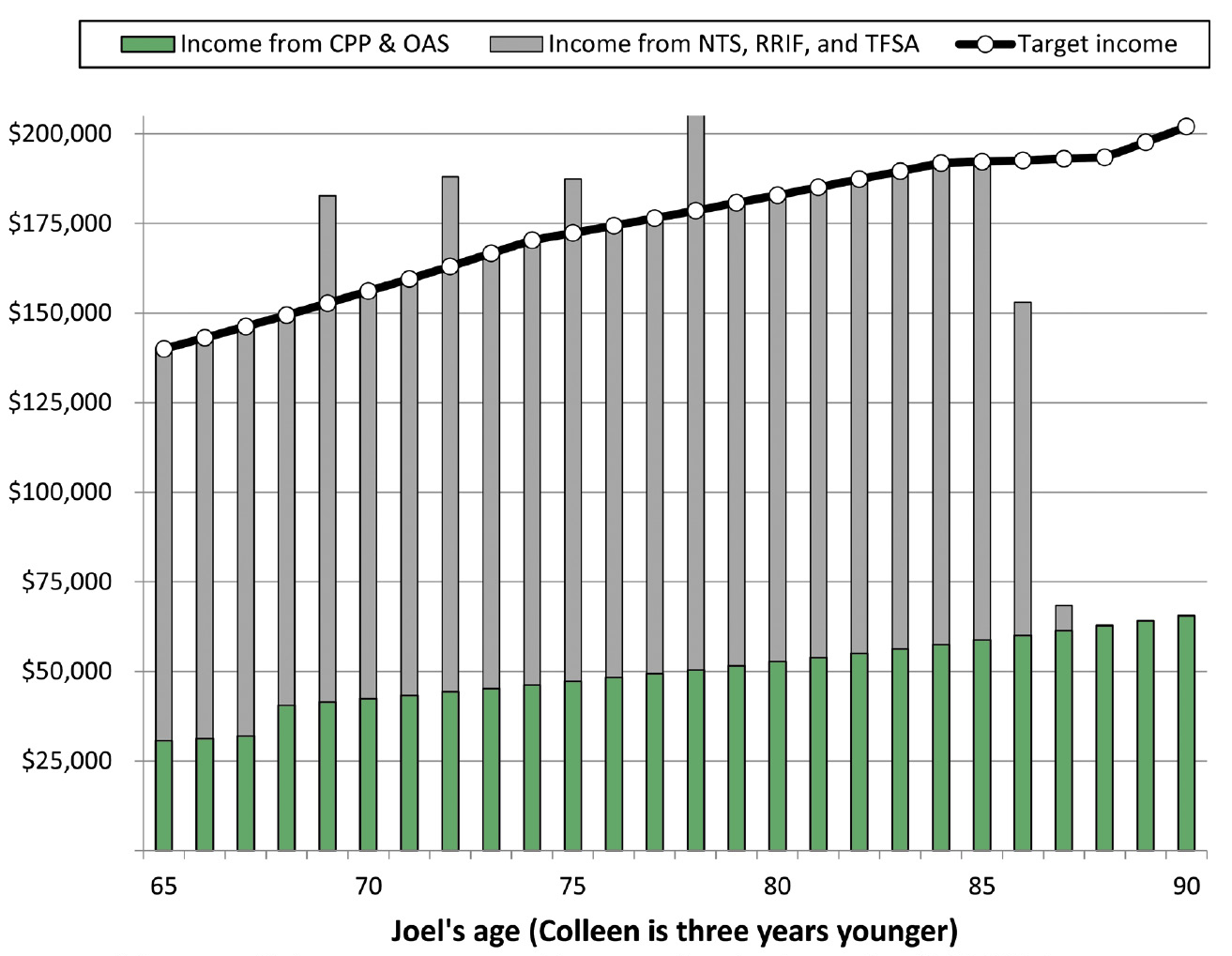

The first thing we will calculate is how long their money will last if they draw total income of $140,000 in year 1 plus inflationary increases in future years. They use PERC (Enhancement 4) to determine this number. In the first scenario, the Clarkes do not adopt any of the enhancements, and as in most of the projections so far, they incur 5th-percentile investment returns. The result is shown in Figure 22.1.

The Clarkes start to run short of money when Joel is 86 and Colleen is 83. This was bad enough in the case of the Thompsons but even worse for the Clarkes, if only because the Clarkes have much higher income expectations. Living off just their CPP and OAS income isn’t really an option for them.

Next, we will add Enhancement 1. Given the size of their portfolio, the Clarkes can probably get their fees down to just 0.5 percent, but we will continue to assume that Enhancement 1 reduces their fees to 0.6 percent, the same as it did for the Thompsons. While not illustrated here, lowering fees makes a significant difference. Their money lasts five years longer than in the previous scenario. On the other hand, lower fees alone do not ensure total security, as they have no assets left to generate income by the time Joel is 91 and Colleen is 88.

Figure 21.2. The Wongs adopt Enhancements 2 and 3

5th-percentile investment returns. Four spending shocks totaling $110,000. Investment fees of 1.8%. Asset mix is 50-50.

We then add in Enhancement 2, deferring CPP to 70. So long as one of them lives to a ripe old age, this further change helps significantly. Their money now lasts until Joel is 95.

Finally, we test to see whether Enhancement 3 (buying an annuity) helps much. The result is that they now have $157,000 in assets remaining at age 95 versus almost none after we added Enhancement 2. In addition, the amount of secure income — from CPP, OAS, and an annuity — is now higher, which would be important in the unlikely event that their investments do even more poorly than the 5th-percentile returns we have been assuming.

This last scenario is a good outcome, but not one that means very much to the Clarkes unless one of them lives beyond 95. Moreover, it will not help at all if their investment returns are closer to the median rather than the 5th percentile.

By the way, if the Clarkes had bought an annuity with 30 percent of their RRIF assets instead of 20 percent, the amount of money they would still have left at age 95 more than doubles to $323,000. Moreover, they would have a higher level of secure income in each year leading up to age 95. Depending on how risk-averse the Clarkes are, this higher allocation to annuities might look quite attractive.

Because of the Clarkes’ greater financial resources, another option is open to them that wasn’t readily available to the Thompsons. Not only should they defer their CPP to age 70, they should defer their OAS pensions to 70 as well. You will recall that deferring OAS by five years increases the amount of pension payable by 36 percent. In the case of middle-income couples like the Thompsons, I didn’t endorse this strategy because it accelerates the drawdown of savings beyond the point at which most people would feel comfortable. This shouldn’t be an issue for the Clarkes.

By deferring OAS to 70, the Clarkes can buy a little extra peace of mind. In the event of worst-case investment returns, they end up having another $100,000 in assets remaining when Joel is 95. They also have a higher level of secure income in each year up to that age.

The most important insight we can get from these projections is that Enhancement 1 (reduced fees) is by far the most important of the three enhancements in the case of high-net-worth individuals.

Deferring CPP to 70 is also worthwhile, as it provides much better income security in their late 80s and does so at no cost. This enhancement would be less valuable if the Clarkes still had employment income beyond age 65. In that case, they might be better off starting their CPP pensions at 65. (See Appendix D for more on this point.)

As for purchasing an annuity, it makes a difference only in the most extreme situations (such as when investment returns are especially poor or lifespans are unusually long) and even then, the difference is not that great. On the other hand, buying the annuity is never a terrible idea.

Finally, I note that at higher-income levels, the OAS clawback might also come into play and could affect the implementation of the enhancements. Its impact is marginal, however, even in the case of Joel and Colleen. One needs very high income for the clawback to be much of a factor, so we will ignore it in our projections.

Takeaways

- Enhancement 1 is hugely important for high-net-worth couples. So is Enhancement 4.

- Enhancements 2 and 3 also have a positive effect for high-net-worth couples, but they are not nearly as important as they are for middle-income retirees.

- High-net-worth couples should also defer OAS to 70.