Chapter 3

The Thompsons Face Financial Ruin

The Thompsons had hoped to achieve a median return on their investments. When one invests in risky assets, though, even such a modest goal is far from guaranteed. In the case of the Thompsons, the capital markets do not co-operate.

As it happens, the Thompsons end up retiring precisely when the long bull market for stocks has finally run its course. Stocks fall sharply from all-time highs and then languish in the doldrums for a prolonged period. This is similar to what happened in the 1970s in North America. It occurred again in the United States in the 2000s, a period known as the lost decade for purposes of investing. Japan has been mired in this state since the early 1990s.

Even the fixed income part of their portfolio (which they invested in a bond fund) does not do too well. That is because interest rates in this nightmare scenario inch up from their ultra-low levels over a period of several years. While that sounds like a good thing, rising interest rates create capital losses on longer-term bonds.

They Suffer Spending Shocks

To compound their misery, the Thompsons incurred some unexpected expenses. Five years into retirement, they had to replace their roof. They did their best to cut back on other spending to make up for it but still ended up drawing $20,000 more income that year than they had planned.

Three years later, their son, Brett, ran into financial trouble of his own. He had bought his first house but then lost his job and couldn’t make ends meet for a few months. Like the good parents they are, Nick and Susan stepped in to help. They dipped into their RRIF to give Brett $20,000 and cut back on their own spending by $4,000 in that year.

And finally, at age 78, Nick had a surgical procedure that restricted his activities for six months. The out-of-pocket expenses that Nick and Susan incurred, including hiring caregivers for a few months, set them back another $25,000. Once again, they cut back on other discretionary spending (like travel) while Nick was recovering so their net over-spending that year was $18,000.

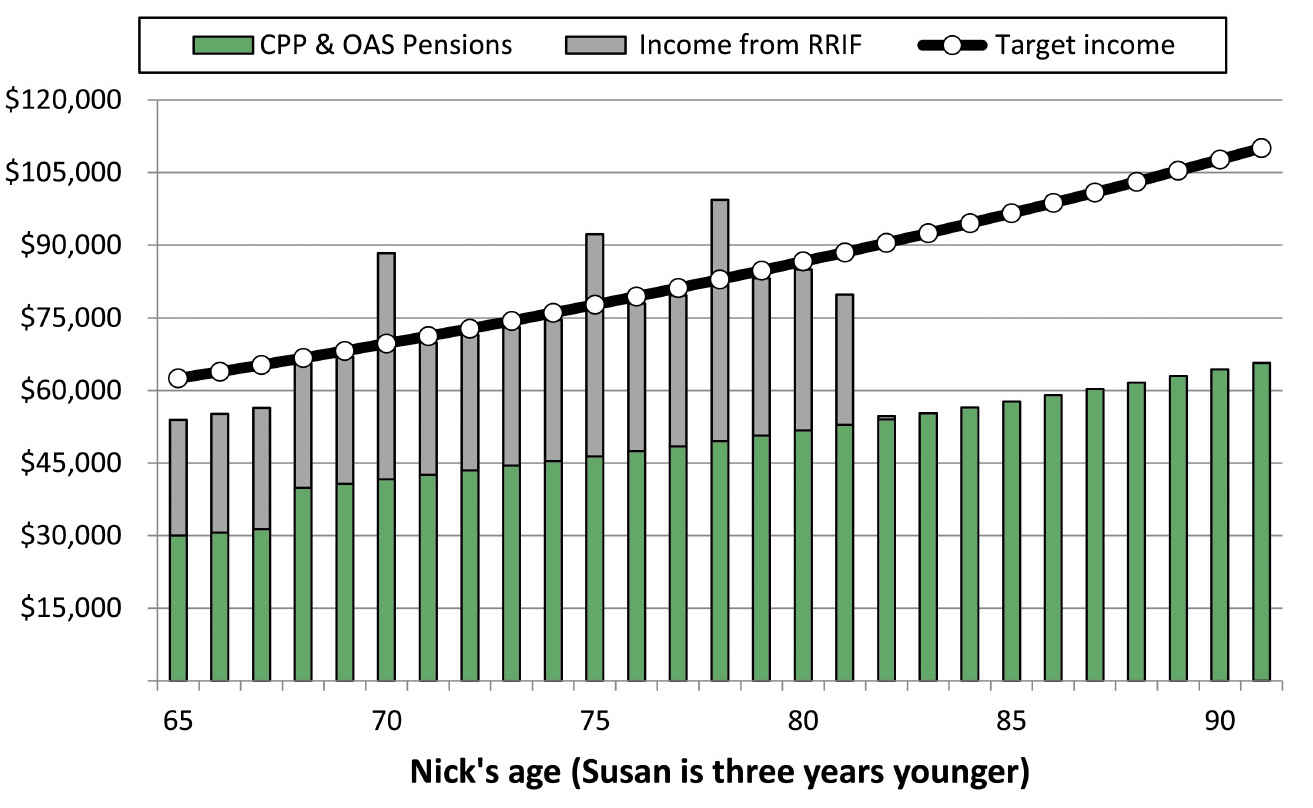

Figure 3.1. Actual result: the Thompsons outlive their savings

The Thompsons suffer worst-case investment returns. The spikes in income at 70, 75, and 78 reflect higher withdrawals to cover spending shocks. RRIF income runs dry by the time Nick is 81.

In spite of the investment losses and the unexpected expenses, Nick and Susan gamely stuck to the 4-percent rule and increased their income from the RRIF by the rate of inflation. As Figure 3.1 shows, the result was not pretty. They exhaust their RRIF assets by the time Nick is 81 and Susan is 78, which is a real problem since they could very well live another 15 years.

Could This Result Have Been Avoided?

Clearly, doing everything “by the book” does not guarantee a positive outcome as real life has a way of offering up nasty surprises. This is certainly true in the case of spending shocks, which are hard to avoid, but you could prepare yourself for them a little better and be ready (at least financially) when they occur. This is the subject of the next chapter.

Even more problematic than the spending shocks was the use of the 4-percent rule to determine income each year. As we will learn in Chapters 5 and 6, better solutions are out there.

On the question of investment risk, it is fair to ask whether the Thompsons took on too much risk by putting half their money in stocks after retirement. I will save this issue for Chapters 7 and 8.

Ultimately, I will show that the Thompsons could have started out with the same $600,000 in assets, encountered the same spending shocks and poor investment returns, and still enjoyed a comfortable standard of living for the rest of their lives.

Takeaways

- Decumulation is not as straightforward as it seems; disaster can strike even if you save a lot and follow a widely accepted decumulation strategy.

- The 4-percent rule doesn’t work when investment returns are very poor.