CHAPTER 2

Hiding in Plain Sight: An Army of Jobless Men, Lost in an Overlooked Depression

MUCH CURRENT ANALYSIS of labor market conditions paints a cautiously optimistic—even unabashedly positive—picture of job trends. But easily accessible data demonstrate that we are, in reality, living through an extended period of extraordinary, Great Depression-scale underutilization of male manpower, and this severe “work deficit” for men has gradually worsened over time.

Expert opinions on U.S. labor market performance have been increasingly sanguine over the past year or so. A few select media headlines and quotations illustrate the emerging consensus:

•“The Jobless Numbers Aren’t Just Good, They’re Great” (August 2015, Bloomberg1)

•“The Jobs Report Is Even Better Than It Looks” (November 2015, FiveThirtyEight2)

•“Healthy Job Market at Odds with Global Gloom” (March 2016, Wall Street Journal3)

•An excerpt from “Two Sides to Economic Recovery: Growth Stalls, While Jobs Soar” stated: “The job market, according to Labor Department figures released in recent months, is at its healthiest point since the boom of the late 1990s.” (April 2016, International New York Times4)

•“June’s Super Jobs Report (July 2016, Atlantic Monthly5)

In addition, U.S. economists and policymakers who have served under Republican and Democratic presidents maintain that today’s U.S. economy is either near or at “full employment”:

•“It is encouraging to see that the U.S. economy is approaching full employment with low inflation.” (Ben Bernanke, former chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, October 20156)

•“The American economy is in good shape . . . we are essentially at full employment . . . tight labor markets are leading to increases in hourly earnings and in the producer prices of services.” (Martin Feldstein, former chair of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers and longtime director of the National Bureau of Economic Research, February 20167)

•“We are coming close to [the Federal Reserve’s] assigned congressional goal of full employment. [Many measures of unemployment] really suggest a labor market that is vastly improved.” (Janet Yellen, chairman of the Federal Reserve, April 20168)

All of these assessments draw upon data on labor market dynamics: job openings, new hires, “quit ratios,” unemployment filings and the like. And all those data are informative—as far as they go. But they miss also something, a big something: the deterioration of work rates for American men.

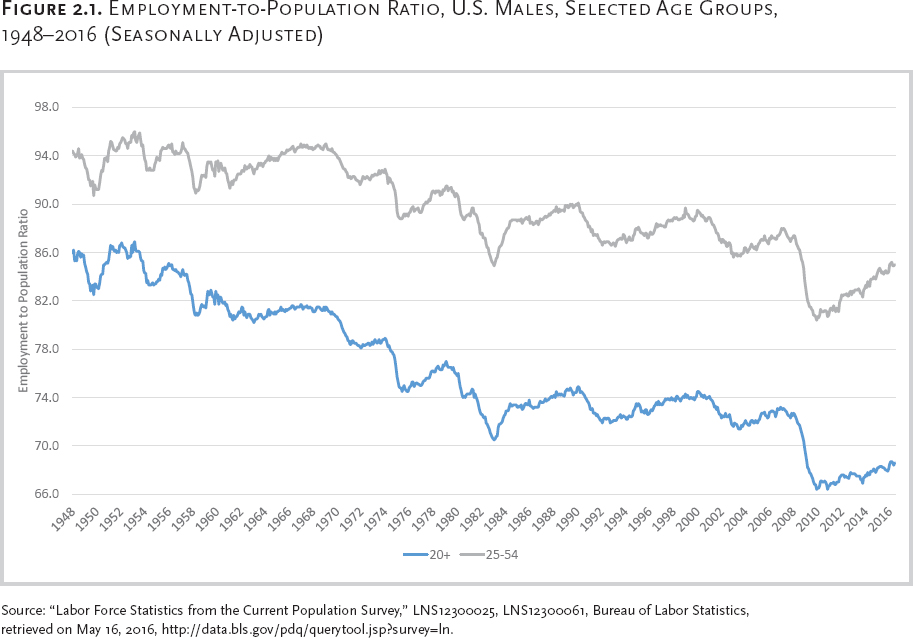

The pronouncements above stand in stark contrast to the trends illustrated in figure 2.1, which track officially estimated work rates for U.S. men over the postwar era (see figure 2.1).

The federal government did not begin releasing continuous monthly data on U.S. employment until after World War II. By any broad measure, U.S. employment-to-population rates for civilian, noninstitutionalized men in 2015 were close to their lowest levels on record—and vastly lower than levels in earlier postwar decades.9

Between 1948 and 2015, the work rate for U.S. men twenty and older fell from 85.8 percent to 68.2 percent. Thus the proportion of American men twenty and older without paid work more than doubled, from 14 percent to almost 32 percent. Granted, the work rate for adult men in 2015 was over a percentage point higher than 2010 (its all-time low). But purportedly “near full employment” conditions notwithstanding, the work rate for the twenty-plus male was more than a fifth lower in 2015 than in 1948.

Of course, the twenty-plus work rate measure includes men sixty-five and older, men of classic retirement age. But when the sixty-five-plus population is excluded, work rates trace a long march downward here, too. By 2015, nearly 22 percent of U.S. men between the ages of twenty and sixty-five were not engaged in paid work of any kind, and the work rate for this grouping was nearly 12.5 percentage points below its 1948 level. In short, the fraction of U.S. men from ages twenty-to-sixty-four not at work in 2015 was 2.3 times higher than it had been in 1948.

As for “prime-age” men—the twenty-five-to-fifty-four group that historically always has the highest employment—work rates fell from 94.1 percent in 1948 to 84.3 percent in 2015. Under today’s “near-full employment” norm, a monthly average of nearly one in six prime-age men had no paying job of any kind.

Though the work rate for prime-age men has recovered to some degree since 2010, the latest report as of this writing (July 2016) is barely on par with the lowest-ever Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reading before the Crash of 2008 (the depths of the early 1980s recession). In 2015, the proportion of prime-age men without jobs was over 2.5 times higher than in 1948. Indeed, 1948 work rates for men in their late fifties and early sixties were slightly higher than for prime-age men today.

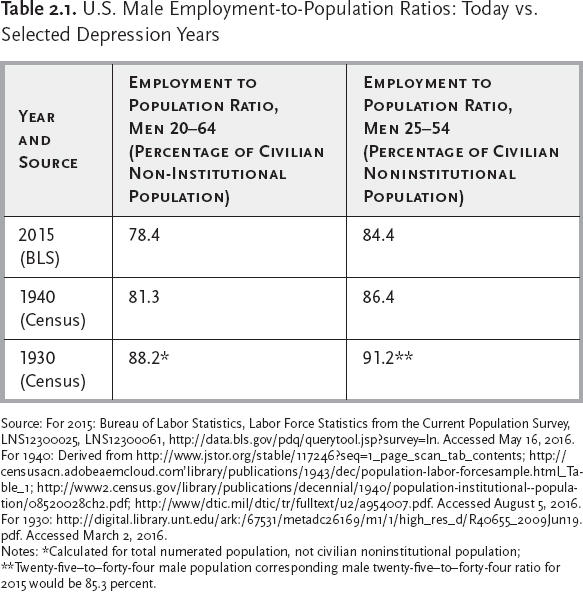

Even more shocking is the comparison of work rates for prime-age men today with those from the prewar Depression era.

During the Depression era, we did not possess our current official statistical apparatus for continuously monitoring employment conditions. Our postwar statistical apparatus for continuously monitoring employment conditions only came in response to the prewar employment crisis. Consequently, our main source of information on Depression-era employment comes from our decennial population censuses. As fate would have it, the Great Depression spanned two national censuses, the 1930 census, near the start of the Depression, and the 1940 census, near its end.10 We contrapose male employment patterns then and now in table 2.1.

According the 1940 census, the work rate for civilian non-institutional men twenty-to-sixty-four years old was 81.3 percent. In 2015, that rate was 78.4 percent. The work rate for prime-age males in 1940 was reported to be 86.5 percent, two points higher than in 2015 and about a point and a half higher than readings thus far for 2016. In other words, work rates for men appear to be lower today than they were late in the Great Depression when the civilian unemployment rate ran above 14 percent.11 Furthermore, the work rate for American men is manifestly lower today than it was in 1930, to judge by returns from the 1930 census.

Admittedly, the comparison is not straightforward, since the 1930 census used different questions about employment status than we use today and did not break out “civilian noninstitutional population” from the total adult population. Nonetheless, the Census Bureau has harmonized those 1930 employment figures with modern definitions of work and joblessness.12 By these reconstructions, the 1930 ratio for employment to total population for men twenty-to-sixty-four was over 88 percent. Among men twenty-five to forty-four (prime work ages for that era) the ratio for employment to total population was over 91 percent. In 2015, the official work rate for working-age men twenty-to-sixty-four was nearly ten percentage points below this 1930 figure (78.4 percent vs. 88.2 percent) and for men twenty-five to forty-four, the nominal gap was nearly six points (85.3 percent vs. 91.2 percent). These numerical differences, I should note, understate slightly the true work rate gap between adult men in 1930 and today, since the 1930 numbers do not exclude men in the armed forces, prisons, long-term hospitalization, etc., from the demographic denominator by which current work rates for the “civilian noninstitutional” population are calculated.

To be clear, the employment disaster in the depths of the Great Depression was unquestionably worse than it was in either 1930 or 1940.13 For better or worse, however, we only have these two census data points for that era’s labor market conditions, and current data indicate that work rates for American men are lower today than in either of these years. It is thus meaningful to talk about work rates for American men today as being at Depression-era levels. In fact, they are more depressed than those recorded in particular years of the Great Depression.

Just how great is our current “work deficit” for American men? One reasonable benchmark for measuring that gap might be the mid-1960s. Then, the U.S. economy was strong and labor markets functioned at genuinely full employment levels.

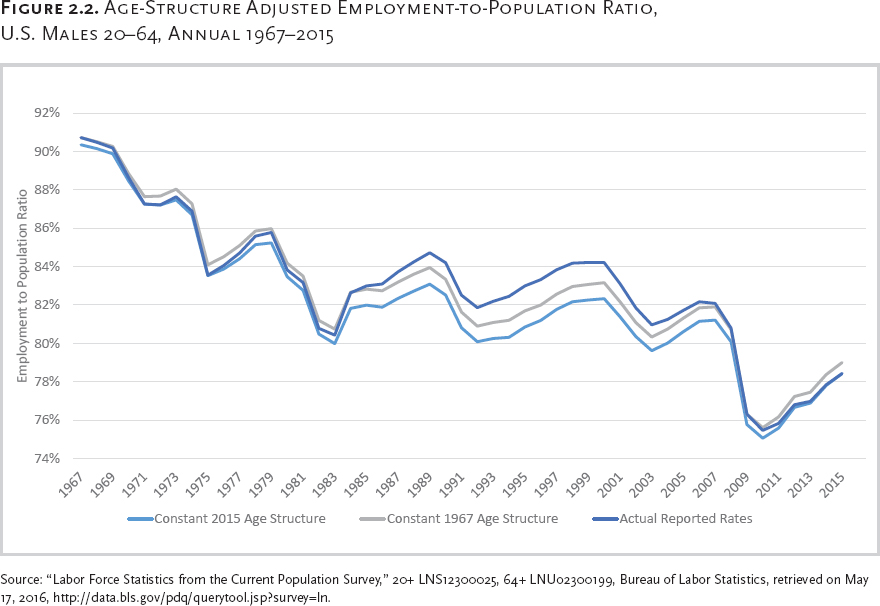

Between 1965 and 2015, work rates for men twenty and older fell by over 13 percent. Population aging cannot account for most of this massive decline: nearly four-fifths of that drop was due to age-specific declines in work rates or 1967–2015 (the period for which more detailed data are available for such calculations). Over these same years, work rates for men in the broad twenty-to-sixty-four group fell from 90 percent to less than 79 percent. In other words, over the two generations, the fraction of men without jobs of any sort in the broad twenty-to-sixty-four group went from 10 percent of the total to almost 22 percent). Almost none of that decline can be attributed to changes in age structure (see figure 2.2). For the critical prime-age group (men twenty-five-to-fifty-four), work rates dropped over this half century from about 94 percent to just over 84 percent. Consequently, the percentage of wholly jobless prime-age men shot from 6 percent to nearly 16 percent.

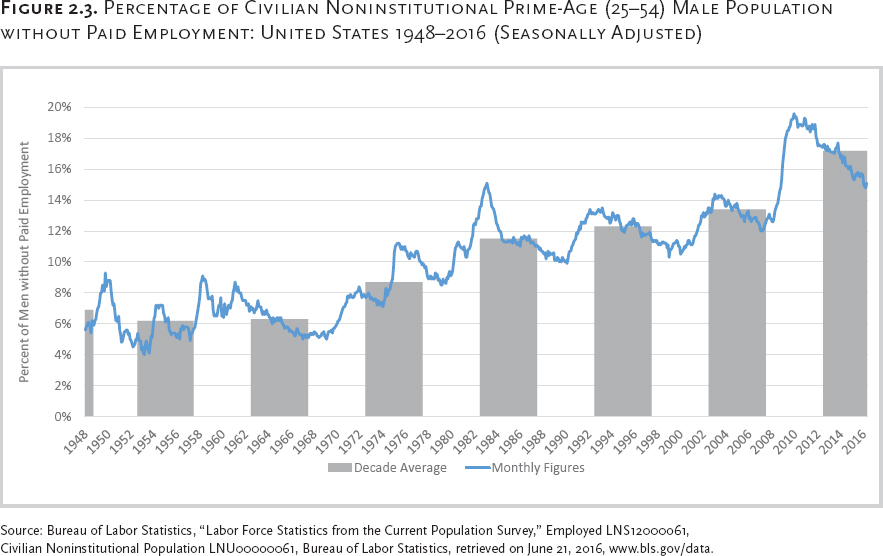

If we look at the long-term trends over the postwar era, we see an eerie and radical transformation in the condition of prime-age men: the unrelenting ratcheting upward in the fraction of men without any paid employment (see figure 2.3). In the decade of the 1960s, monthly averages indicated that one in sixteen prime-age American men were not at work. By the 1990s, the ratio had jumped to one in eight. In the current decade (January 2010 to June 2016), the ratio has dropped below one in six for an average of 17.5 percent of prime-age men with no paid work in the past month.14

What does all this mean for the current “work deficit” for grown men? If age-specific work rates for the civilian noninstitutional adult population had simply held constant from 1965 to today, over 10.5 million additional men ages twenty-to-sixty-four would have been working for pay in 2015 America, including an additional 6 million men in the prime twenty-five-to-fifty-four group.15

In one important respect, however, this 10.5-million-plus figure overstates today’s “deficit” for men. The reason: it fails to account for the steady increase in education and training for adult men over the past five decades. Education and work-related training can temporarily take work-minded men out of the workforce. It’s critical to make adjustments for these factors to get a meaningful sense of the true falloff in paid employment for men in modern America.

Unfortunately, making these adjustments is not such a straightforward task. Statistics on training are notoriously limited, inconsistent, and contradictory.15 Numbers on formal education can also be problematic. Nevertheless, by 2014 (the latest figures available), nearly a million more men in their early twenties were in school than would have been the case with 1965 enrollment ratios.16 For men twenty-five-to-sixty-four, the corresponding number exceeded 1.6 million.17 These numbers suggest that at least 2.5 million more adult men were in education or training in 2014 than in 1965.

Of course, not all of these men would have been out of work pursuing work-related education or training. It’s actually quite the contrary. The overwhelming majority of adult male job trainees appear to be job holders already. That is the nature of job-related training. As for formal education, most men of all adult ages enrolled in formal schooling are also in the workforce. They are typically part-time student workers or part-time working students. In 2014, according to Current Population Survey (CPS) data from the Census Bureau, 55 percent of all men twenty and older enrolled in schooling were simultaneously working paid jobs. The same was true for nearly 70 percent of men twenty-five-to-fifty-four years of age.18 So the real question becomes what proportion of the additional men in school or training were out of the workforce because they were in school or training.

Roughly speaking, CPS data indicate that adult schooling per se is currently taking about a million more working-age men out of the paid workforce today than would have been the case if the twenty-plus population conformed to 1965-era enrollment ratios.19 (Not all of this schooling is directly or even indirectly employment related.) If we deduct this million from the 10.5 million figure above, the “corrected” total for 2015 would be approximately 9.5 million.

In sum, even after (generously) adjusting for today’s demanding regimen of adult schooling and training, the net “jobs deficit” in 2015 for men twenty-to-sixty-four in relation to 1965-era work patterns would come out to a number approaching 10 million. The implied employment deficit works out to around 1.2 million for men in their early twenties and about 5.5 million for prime-age men twenty-five-to-fifty-four, with the remainder being men in their late fifties and early sixties.

If 1965-style employment patterns applied today, an additional 10-plus percent of America’s civilian noninstitutional male population between the ages of twenty and sixty-five would have been working and earning a paycheck in 2015, even after taking educational expansion into account. We would also have about 10 percent more men at work in the prime-age years than we do today.

Romans used the word “decimation” to describe the loss of a tenth of a given unit of men. The United States has suffered something akin to a decimation of its male workforce over the past fifty years. This disturbing situation is our “new normal.” No less disturbing is the fact that the general public and political elites have uncritically accepted this American decimation as today’s “new normal.”

Today’s received wisdom holds that the United States is now at or near “full employment.” An alternative view would hold that, by not-so-distant historic standards, the nation today is short of full employment by nearly 10 million male workers (to say nothing of the additional current “jobs deficit” for women). Unlike the dead soldiers in Roman antiquity, our decimated men still live and walk among us, though in an existence without productive economic purpose. We might say those many millions of men without work constitute a sort of invisible army, ghost soldiers lost in an overlooked, modern-day depression.