CHAPTER 7

Long-Term Structural Forces and the Decline of Work for American Men

THUS FAR I have examined the dimensions of the collapse of work for men over the past half century, the role of the ongoing flight from work in this collapse, the poor LFPRs today of U.S. men in relation to those in other affluent Western countries, the changing sociodemographic characteristics of the American man who is neither working nor looking for work, and the time-use and social participation patterns of the un-working American man. Our examination of modern America’s “men without work” problem, however, has yet to touch upon the role of momentous changes in the postwar U.S. economy in exacerbating this problem—or perhaps in creating it altogether.

Any account of America’s growing male work problem that does not recognize that macroeconomic changes have played a part in this troubling dynamic cannot help but be incomplete. Therefore, it’s important to summarize some of the thinking and evidence suggesting that long-term structural forces (including such things as international trade, technological and financial innovation, outsourcing, the rise of the on-demand economy, temporary work, and other trends shaping aggregate demand) may be responsible for much, if not most, of the decline in work for men in postwar America.

A 2016 report by the president’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) did a good job of laying out this case.1 After documenting the long-term decline in prime-age male workforce participation rates and sorting out some of its components, the report rightly suggested that these long-term labor force trends can be explained in terms of three different kinds of effect: (1) supply side, (2) demand side, and (3) institutional. This chapter will focus on the demand-side effect.

Structural and macroeconomic forces would be demand-side explanations for declining employment rates and workforce participation. The CEA report offered a careful presentation of the demand-side explanation, focusing particularly on the evidence for decreasing demand for less-skilled labor in postwar America:

If less-educated men were simply choosing to work less . . . this should raise the relative wages of the less-educated men who choose to continue participating in the workforce. Yet, in recent decades the opposite has happened: less-educated Americans have actually suffered a reduction in their wages relative to other groups.

A number of studies have identified declining labor market opportunities for low-skilled workers and related stagnant real wage growth as the most likely explanation for the decline of prime-age male labor force participation, at least for the period in the mid-to late 1970s and 1980s. . . . More recently, economists have suggested that a relative decline in labor demand for occupations that are middle-skilled or middle-paying may have begun contributing to the decline in participation in the 1990s . . . As demand for these middle-skilled workers has fallen, they may have displaced lower-skilled workers from their lower-skilled jobs . . . leading some lower-skilled workers to leave the labor force . . .

Possible causes include technological advances and globalization, including import competition and offshoring . . . Some economists point to “skill-biased technological change”: advances that benefit workers with certain skill sets more than others . . . These forces have, among other things, eliminated large numbers of American manufacturing jobs over a number of decades . . . leaving many people—mostly men—unable to find new ones.2

This passage presents the consensus view among contemporary economists on the dynamics of these “demand-side” forces. Most economists would agree that these structural and macroeconomic changes have depressed demand for labor, especially for less-educated, lower-skilled labor in the postwar era.

I concur with this assessment and would further add that other macroeconomic factors less emphasized in the CEA report—such as the U.S. economy’s relatively disappointing record in generating economic growth since the start of the new century—have also limited demand for work. The question, however, is how significant an impact these “demand-side” factors have had on the collapse of work for American men. We cannot hope to settle that question here, but we can review some of the evidence suggesting that the impact of such structural and macro-economic changes may have been more qualified than some believe.

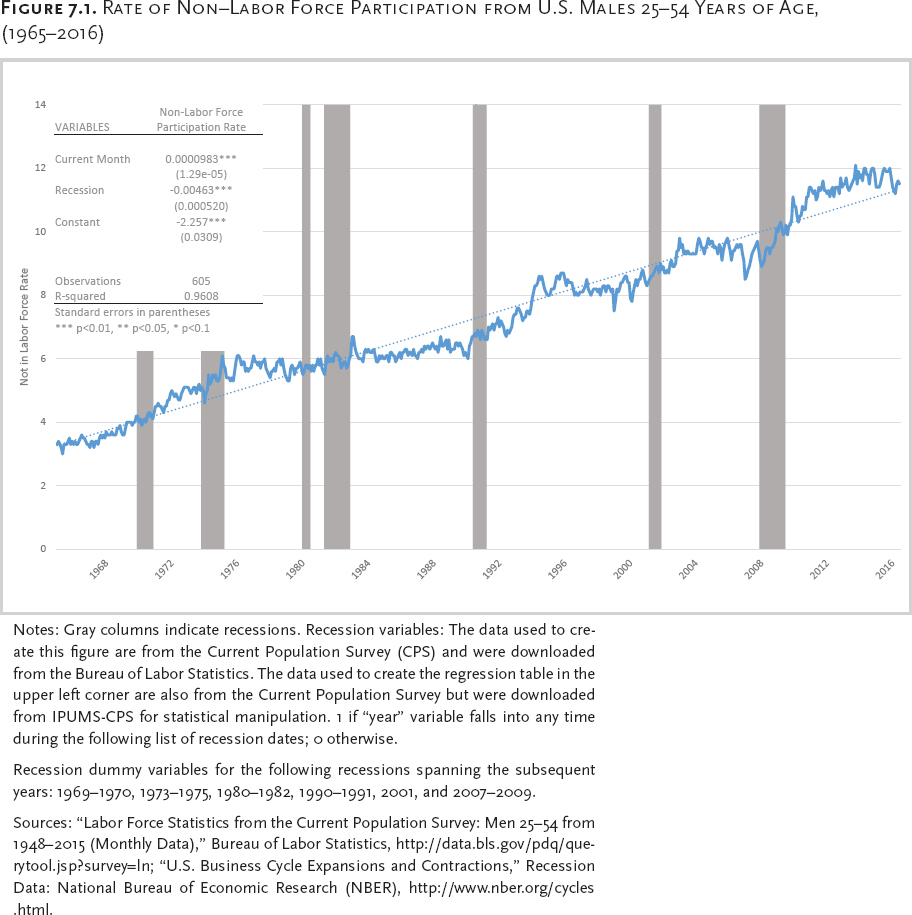

First, there is a remarkably steady decline in LFPRs for prime-age U.S. men over the past fifty years. This decline has now proceeded with nearly clocklike regularity, almost totally uninfluenced by the business cycle, for half a century (see figure 7.1). America suffered seven recessions between 1965 and 2015, but knowing when these recessions occurred gives us no additional information on the trajectory of the prime-age male LFPR decline. (If fact, it actually looks as if recessions may slightly slow the flight from work.) By the same token, knowing whether the U.S. economy was growing rapidly or slowly or, for that matter, contracting provides almost no help in anticipating the pace at which prime-age men would be leaving the labor force. Sociologists and economists once remarked on the curious and counterintuitive nature of this trajectory and presumed it would have to be reversed.3 Today they accept it as a fact of life.4 As Alan Kruger, Princeton economist and former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers for President Obama, remarked in a speech in 2015, “According to CPS data, the monthly rate for transitioning from out of the labor force to back in the labor force is unrelated to the business cycle.”5

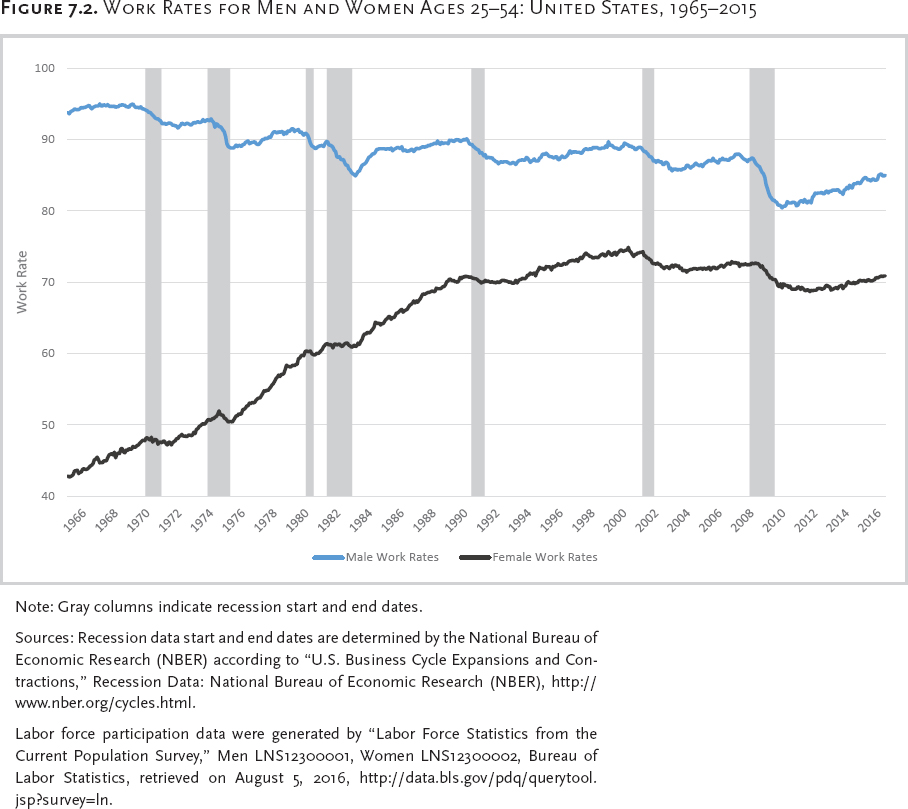

Second, unlike LFPRs, work rates for U.S. men (including prime-age men) fell in recessions and stabilized in recoveries. But work rates for women seem less affected—and in some recessions seem basically unaffected (see figure 7.2). Between 1965 and the late 1990s—over the course of five recessions—prime-age female work rates rose by a cumulative total of over thirty percentage points. It remains to be explained what sort of structural or macroeconomic “demand-side effect” would impact labor demand for only half the U.S. population.

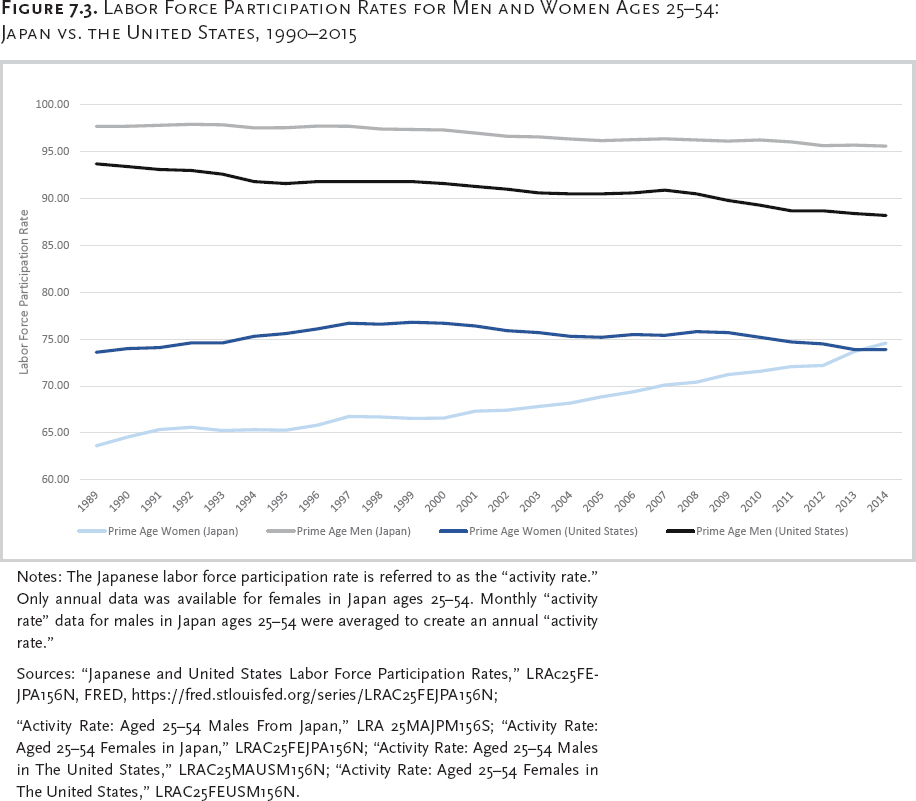

Third, slow growth does not necessarily make for weak labor demand in affluent modern economies (see figure 7.3). Despite a much weaker growth rate, Japan had much stronger labor force participation numbers than the United States even in the “lost decades” of the 1990s, when the U.S. economy was growing robustly. And Japan’s more favorable LFPR trends cannot be written off as a “cultural” anomaly explained by unusually low LFPRs for Japanese women. On the contrary, Japanese female rates rose steadily and, in fact, now exceed U.S. rates for prime-age women.

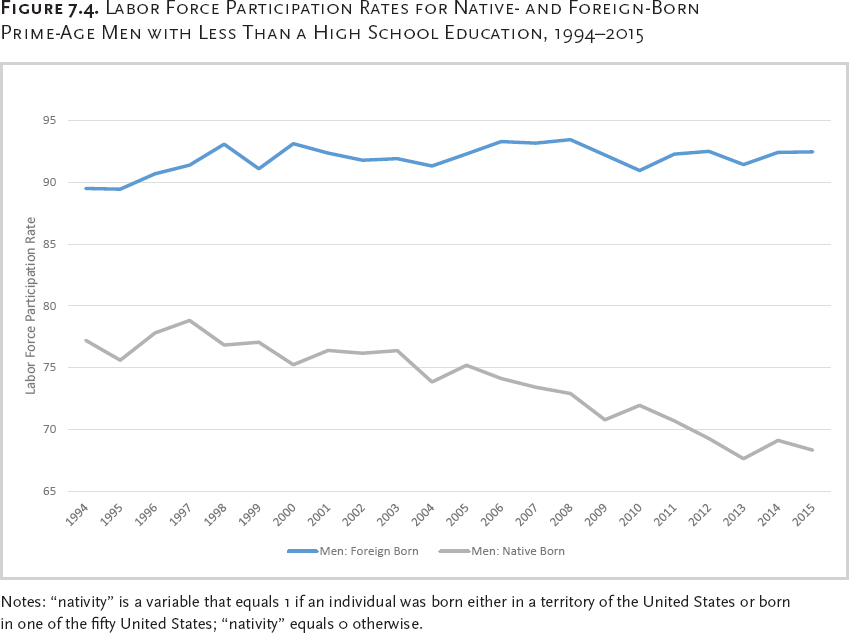

Fourth, not all less-educated prime-age men in America were subject to the negative labor market demand-side effect. A comparison of LFPRs for native-born and foreign-born lower-skilled men of prime working age makes this clear (see figure 7.4). By 2015, the gap between LFPRs for such native and immigrant men without high school degrees was over twenty-four percentage points. Between 1994 and 2015, LFPRs for these native-born prime-age men plunged by nine percentage points. For less-educated immigrants, LFPRs actually rose by over more than three points, to 92.5 percent over the same period of time. If a broad “demand-side” effect is really the dominant reason for the decline in LFPRs for this group, someone needs to explain why important subgroups of the cohort were not subject to it.

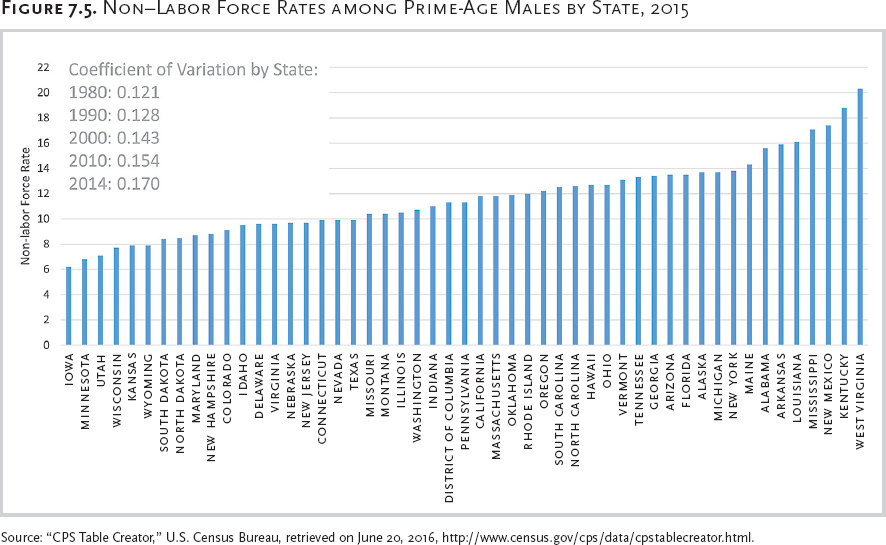

A fifth point is this: if demand-side effects were a truly significant determinant of changes in labor force participation patterns, one might expect that regional differentials would tend to diminish following such “shocks” as labor markets sought equilibrium. But nothing like this has occurred over the past several decades (see figure 7.5). Extreme variation characterized state-level prime-age male NILF levels in 2014, ranging from over 20 percent in West Virginia to 6 percent in Iowa. Moreover, some states with the highest inactivity levels were next to states with the lowest levels: West Virginia (20.3 percent) borders Maryland (8.7 percent), Maine (14.3 percent) borders New Hampshire (8.8 percent), New Mexico (17.4 percent) touches Utah (7.1 percent), and so on. Moreover, these variations have increased over time. Growing long-term regional differences might be explained by institutional effects, as we shall soon see, or even supply-side effects. But this feature of contemporary U.S. labor markets is not easily explained in terms of demand-side effects.

Changes in demand for labor in general and less-skilled labor in particular have certainly played some role in the ominous work trends for U.S. men documented in this study. This is not a small matter of dispute. Specifically, the parallel trends in work-rate decline for prime-age U.S. men and women since roughly 2000 suggest that our relatively weak economic performance since then has reduced employment opportunities in contemporary America. But are such “demand” factors so distinctive and powerful to explain America’s uniquely poor labor force participation trends for prime-age men since the 1960s? It would seem difficult to explain why this should be the case.

Of course, we should all welcome further research on the demand-driven aspect of the male work problem. But I would also suggest that supply-side factors (diminished incentive to work) and institutional factors (legal or other barriers to work) deserve closer examination than they have received in explaining the postwar collapse in male employment rates and the great male flight from work. I focus on these other two factors in the final two chapters.