The leaders of the Union and Confederate armies knew one another well. Many of them had sat together in the classrooms of West Point. They had trained together, become friends, and fought together. They knew the size of one another’s courage, they knew who was bold and who was reticent, they knew whose pride was greater than his good sense, and they knew who let sorrow color his decisions. They knew one another’s strengths and weaknesses; they knew one another’s secrets. This intimate knowledge made the war even more horrible.

Several of them had first been tested during the Mexican-American War, where they had served together under General Winfield Scott. Joe Johnston was there. Thomas Jonathan Jackson—later to gain fame as “Stonewall” Jackson—saw his first combat there. Jefferson Davis, commander of the 1st Mississippi Rifles, helped prevent an inglorious rout during the Battle of Buena Vista. But it was during the decisive Battle of Cerro Gordo that these future leaders truly proved their mettle.

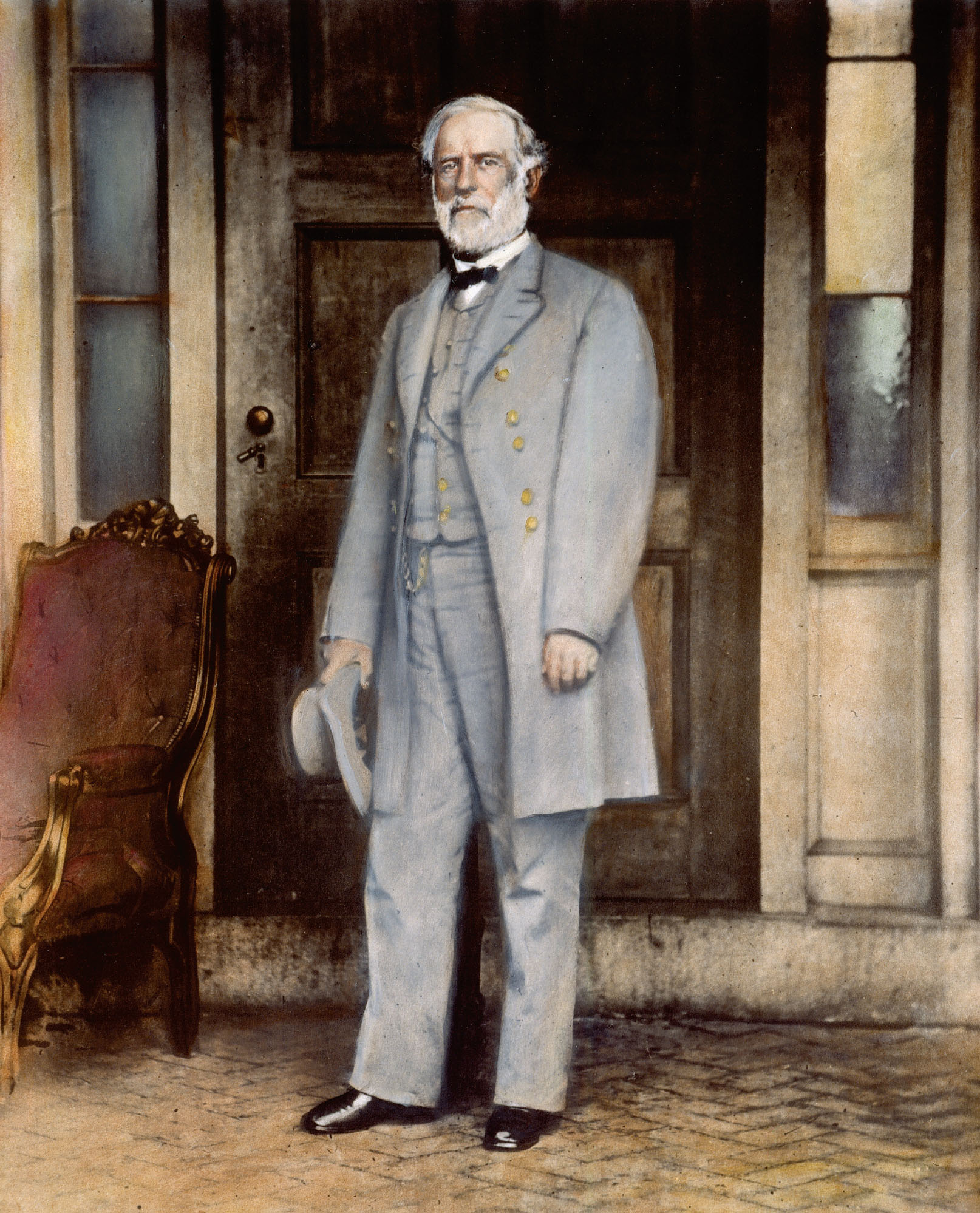

Only a week after his 1865 surrender at Appomattox, General Robert E. Lee agreed to pose outside his Richmond home for Mathew Brady. The series of six poignant photographs—including this hand-tinted portrait—became quite popular.

In April 1847, Mexican general Santa Anna’s twelve thousand well-fortified troops blocked Scott’s path to Mexico City. Scott began preparing a frontal assault, which would have resulted in thousands of casualties. But Lieutenant Pierre G. T. Beauregard believed it was possible to flank Santa Anna’s dug-in troops by cutting a road through seemingly impassable terrain. Lieutenant George McClellan, a skilled engineer, believed that artillery could not be transported over the steep hills and through deep ravines, but Scott sent Captain Robert E. Lee to determine if passage was possible. Lee found the way and, as Lieutenant U. S. Grant wrote in his memoir, “Under the supervision of the engineers, roadways had been opened over chasms to the right where the walls were so steep that men could barely climb them. Animals could not.… The engineers … led the way and the troops followed.”

Lee’s daring, especially contrasted to McClellan’s faith in order, overwhelming force, and a direct attack, captured Scott’s respect and admiration. “He is,” Scott said, “the very best soldier I ever saw in the field.” By the end of the Mexican-American War, he had become a close confidant of Scott’s and had been promoted to the temporary rank of brevet lieutenant colonel.

Following that victorious war, Lee was appointed superintendent of the Military Academy at West Point, where he trained many of the men who would serve under him—and against him—in the Civil War. Although he had inherited slaves and his own position on slavery has long been debated, he wrote in 1856, “There are few, I believe, in this enlightened age, who will not acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil.” But he was not in favor of secession, adding several years later, “I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than the dissolution of the Union.”

The Battle of Cerro Gordo in the Mexican-American War brought together many of the young officers who would lead the armies in the Civil War, including Grant and Lee. Mexican leader Santa Anna was so completely surprised by the flanking attack that he was forced to flee, as seen in this lithograph, without his artificial leg, which was captured and put on display.

As the nation moved closer to war, it was not at all surprising that Lincoln chose Lee to command the Union army. There could not have been a better choice; in addition to his military experience, few men had deeper roots in the founding of the Republic than Lee. He traced his lineage to Henry Lee, a member of the governing council of the Virginia Colony and for a time its acting governor. Two other relatives, Richard Henry Lee and Francis Lightfoot Lee, were the only brothers to sign the Declaration of Independence. His father was General “Light Horse Harry” Lee, a Revolutionary War hero who was present at Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown and later became governor of Virginia. His own father-in-law was the adopted grandson of George Washington. It was his father who put down the historic Whiskey Rebellion against taxation; and it was Robert E. Lee who decades later ended John Brown’s rebellion at Harpers Ferry and brought him to justice.

Lee’s own fate, he knew, was tied to his beloved home state of Virginia. In anticipation of the war he told a friend, “If Virginia stands by the old Union, so will I. But if she secedes … then I will follow my native state with my sword and, if need be, my life.”

The day after Virginia seceded Lincoln offered Lee the command of the United States Army. Undoubtedly Scott pointed out to him that Scott, too, was the son of a Virginian but that he had chosen to honor the oath of allegiance to the federal government he had taken more than fifty years earlier, “with my sword, even if my own native state assails it.” Although Lee had anticipated this agonizing situation, his wife, Mary Lee, described making this decision as “the severest struggle” of his life. How could he take up arms against the South? Even so, Winfield Scott must have been shocked when Lee ended his thirty-two-year career by resigning his commission. “Lee,” Scott snapped, “you have made the greatest mistake of your life.”

Three days later Virginia’s governor appointed Robert E. Lee commander in chief of that state’s military and naval forces. A month later, when those forces were absorbed into the Confederate army, President Jefferson Davis, who while serving as secretary of war a decade earlier had appointed Lee superintendent of West Point, made him his chief military adviser. Like McClellan, Lee initially set about transforming an array of state militias into an army, relying on their common purpose to bring them together as a unified fighting force. His first few months were spent working behind a desk in Richmond. It wasn’t until September that he took command in the field, which proved to be a dismal failure.

General Winfield Scott, who led the American assault on Mexico City, served as an active duty general longer than any man in history. The “Grand Old Man of the Army” was its general in chief for two decades.

Lee’s objective was to rally support for the Confederacy in western Virginia, which did not support secession and within months would form its own government pledging support to the Union. In September 1861, Lee launched an attack on outnumbered Union forces occupying the fort on Cheat Mountain. In his overly complex plan, five columns were to follow different paths up the four-thousand-foot mountain and converge on the fort at the same time. Everything went wrong, there was no communication between those columns, and the attack was called off. Lee barely escaped capture, his son was wounded, and his close friend and relative John Washington was killed. Lee stumbled around western Virginia for the next three months without achieving a single victory.

Lee’s sterling reputation had been badly tarnished. When he was recalled to the capital, the Richmond Examiner reported he had been “outwitted, outmaneuvered and outgeneraled.” Critics began referring to him as “Granny Lee,” “The Great Entrencher,” even the “King of Spades” because his troops too often seemed to be devoted to digging defensive earthworks rather than attacking. Davis reassigned him to supervise the coastal defense of South Carolina.

Redemption came the following spring. The whispers questioning McClellan’s loyalties had grown louder and Lincoln demanded a campaign against Richmond. The president proposed a second overland offensive through Manassas, but McClellan had a more audacious plan. Plagued by poor intelligence from Allan Pinkerton that warned him, woefully inaccurately, that Joe Johnston was waiting at Manassas Junction with as many as 150,000 men, he elected to go around them. McClellan bypassed Manassas entirely by loading his Army of the Potomac on transports and landing 130,000 troops, 15,000 horses and mules, 44 artillery batteries, and sufficient ammunition and supplies at Fort Monroe, intending to march up the peninsula formed by the York and James Rivers to Richmond. Confederate general John Magruder’s small army on the peninsula was badly outnumbered, but, aware of McClellan’s reputation for caution, he marched the same troops back and forth and set decoy campfires to create the impression that many more soldiers were in camp. Captured Confederate prisoners continued the deception, claiming that “Prince John” (as Magruder had been nicknamed at West Point for his acting ability) had 40,000 men and Johnston was only a day away. The ploy worked and, rather than smashing through a weak defensive line and racing to Richmond, McClellan besieged strategically unimportant Yorktown. Lincoln urged him to attack, warning him, “It is indispensable to you that you strike a blow.” The president’s secretary John Hay wrote that the general “sits trembling before the handful of men at Yorktown, afraid either to fight or run.”

Deceived by faulty intelligence, McClellan moved agonizingly slowly against Yorktown, waiting for promised reinforcements. “He is an admirable engineer,” Lincoln once said in frustration, “but he seems to have a special talent for a stationary engine.” While he stalled, Stonewall Jackson was building his own legend in the Shenandoah Valley, marching his small but highly mobile “foot cavalry” as much as thirty miles a day in a brilliant campaign that once again threatened Washington. Secretary of War Edwin McMasters Stanton received intelligence that “leaves no doubt that the enemy in great force are marching on Washington.” “The Great Scare” proved entirely false; the reinforcements McClellan expected were instead ordered to the valley.

But Lincoln was done waiting, ordering McClellan to “either attack Richmond or give up the job.” The day before McClellan launched his assault on Yorktown the fifteen thousand Confederates in that city slipped away, preparing for the defense of the capital. As McClellan’s Army of the Potomac moved cautiously closer to Richmond, the outnumbered Johnston decided to attack before all of McClellan’s forces crossed the treacherous Chickahominy River. It was a fight that changed the war, although no one could have imagined it. Johnston’s plan worked, pushing Union forces back, until reinforcements were able to make it across the river. In a hectic battle at Fair Oaks, Johnston rode along his lines—and was hit by two shots and knocked unconscious; he fell from his horse.

The battle continued into a second day. Union troops pushed to within four miles of Richmond, then paused and withdrew to an earlier position. Once again, McClellan camped to await reinforcements.

The injured Johnston could no longer command the army. Davis put Robert E. Lee in charge. That little twist of fate, born of necessity, would make all the difference. Lee had spent his life preparing for this command; he had a genius for military strategy, he had the respect of his army, and he was supremely confident. Within months he would fight his way into American history.

During the war publishers in both the North and South produced maps of the battles for a public with an almost insatiable desire for the latest news. So many families had relatives in the war that there was a widespread hunger for any reports. This is a map of the second day’s fighting in the Seven Days’ Battle of June and July 1862.

Lee inherited a dispirited army. Morale and supplies were low and his army was facing a far superior force. After securing his defenses to make certain the bluecoats would pay in blood for every yard of dirt they gained, Lee attacked the Union left flank at Mechanicsville. That attack failed, at least partially because once again his generals were not yet able to carry out his strategy, and he suffered grievous casualties. But rather than settling for the temporary safety of Richmond, he quickly launched another attack, and another, and yet another. The rebels attacked McClellan’s men at Gaines’s Mill, at Garnett’s and Golding’s Farm, at Savage’s Station, and at White Oak Swamp. He suffered tremendous casualties but continued to attack, threatening to sever McClellan’s supply lines. In fact, Lee remained so calm and proud throughout the entire Seven Days’ Battle, never showing the slightest emotion, that his men began calling him the Marble Man.

Unlike McClellan, who rarely appeared on a battlefield, both Lee and Stonewall Jackson liked to be in the thick of the fighting. In fact, later in the war, when Lee’s men urged him to stay safely in the rear, he uttered his famous words of caution, “It is well that war is so terrible, lest we should grow too fond of it.”

Lee had taken a great gamble with his audacious strategy: by attacking he had left Richmond vulnerable. But he had the measure of his opponent, feeling confident that McClellan would not risk an all-out assault on the city. He was right. McClellan was convinced that Lee had positioned 110,000 men between the Union army and the city—while in fact there were fewer than 30,000. The war might have been won that week, but McClellan instead protected his army. Union general Philip Kearny begged McClellan to allow him to march on the Confederate capital, telling him, “I can go straight into Richmond! A single division can do it, but to play safe, use two divisions.”

Finally, relentless rebel attacks pushed the Union troops back across the Chickahominy, back down the Virginia Peninsula, and away from the capital. Richmond was saved. As McClellan retreated, the irate Kearny laced into him, telling him in front of other officers, “I … protest against this order for retreat. We ought, instead of retreating, to follow up the enemy and take Richmond; and, in full view of all the responsibility of such a declaration, I say to you all, such an order can only be prompted by cowardice or treason.”

McClellan still did not understand how badly he had been outmaneuvered by Lee, telegraphing Stanton, “I have lost this battle because my force was too small.… I have seen too many dead and wounded comrades to feel otherwise than that the government has not sustained this army.… I owe no thanks to you or to any other persons in Washington. You have done your best to sacrifice this army.”

General Scott called General Philip Kearny, seen here leading a charge at the Battle of Chantilly on September 1, 1862, “the bravest man I ever knew.” When Kearny was killed several hours later, after encountering a rebel patrol, Confederate general A. P. Hill said sadly, “He deserved a better fate than to die in the mud.”

Lincoln responded diplomatically: With Stonewall Jackson victorious in the Shenandoah Valley, he said, he needed sufficient troops to protect Washington. But he was done with McClellan’s incessant requests for more and more troops.

Lee emerged from the Seven Days’ Battle a Confederate hero, although personally he was extremely disappointed he was not able to pursue and destroy McClellan’s army. It is difficult to appreciate the awe in which Robert E. Lee was held throughout the South. The Confederacy was at war with a substantially larger force from a far more industrialized region capable of properly supplying its army, while the Southern agrarian economy was stagnating. Most industrial production in the South fell into Union hands early in the war. But what they lacked in resources they made up for in determination. While many Northerners wondered why they were fighting this war, Southerners knew they were defending their unique culture. For them slavery was both an economic necessity and the symbol of white racial superiority. What Lee gave them was hope and the noble sense that they were fighting to protect their homes and history rather than slavery. Winning a war against a larger, better-equipped army required the kind of courage, tactical skill, and inspired leadership that Lee had demonstrated. He exemplified the Southern man of honor who had given up his home and his career to fight for the cause. Robert E. Lee literally was a man for whom his troops would give their lives. Faith was an important weapon, and the South believed in him.

With each battlefield success Lee’s legend grew larger. Part of that legend was his relationship with his noble horse, Traveller. In those times, a man’s horse could make the difference between living and dying. A horse that responded quickly, that wasn’t spooked by battle sounds, that could be ridden long and hard was invaluable. That was Traveller, who himself became such a celebrity that his tail and mane were thinned by people plucking hairs as souvenirs. Stephen Vincent Benét described him in an excerpt from his epic poem John Brown’s Body, titled “Army of Northern Virginia”:

And now at last,

Comes Traveller and his master. Look at them well.

The horse is an iron-grey, sixteen hands high,

Short back, deep chest, strong haunch, flat legs, small head,

Delicate ear, quick eye, black mane and tail,

Wise brain, obedient mouth.

Few images inspired more pride and confidence throughout the Confederacy than that of Robert E. Lee astride his noble steed Traveller. This is from an oil painting by L. Valdemar Fischer.

Lee had purchased the four-year-old American Saddlebred, who had been named Jeff Davis at birth, for $200 in 1861. He was a high-spirited horse, and Lee named him Traveller because he moved so beautifully. While he was not Lee’s only horse, he was the one Lee rode throughout the major battles of the war, from the Seven Days’ Battle through to the end.

Lincoln’s admiration for Lee had led him to offer him command of the Union army, so he must have watched in dismay as Lee took charge of the Confederate army. Lee’s boldness served to magnify McClellan’s reticence. His bravado made McClellan’s steady but dull nature appear even more lackluster. Lincoln searched his officer corps for a man who would stand up against Lee, and he thought he’d found him in General John Pope.

Lincoln and Pope had known each other in Illinois, where the president had argued cases in front of the general’s father, Judge Nathaniel Pope. After being named commander of the Army of the Mississippi early in 1862, John Pope had distinguished himself with a victory at Island No. 10 in which he’d lost only twenty-three men while taking five thousand Confederate prisoners, successfully opening the upper Mississippi to the federal army. After being ordered east and given command of the Army of Virginia, he undoubtedly earned Lincoln’s favor when he told the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, “I mean to attack … at all times that I can get the opportunity.”

War news spread slowly, but each battle seemed monumentally important. The weeklong Battle of Island No. 10, fought on land and river, opened the upper Mississippi to the Union navy and threatened to cut the Confederacy in half.

Finally.

While John Pope had indeed enjoyed military success, his true gift was self-promotion. Almost immediately he earned the disdain of the veteran soldiers in his new command, belittling their sacrifices and their courage while severely criticizing McClellan, telling them,

I have come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies; from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary and to beat him when he was found; whose policy has been attack and not defense.… I am sure that you long for an opportunity to win the distinction you are capable of achieving. That chance I shall endeavor to give you. Meantime I desire you to dismiss from your minds certain phrases which I am sorry to find so much in vogue amongst you. I hear constant talk of “taking strong positions and holding them,” of “lines of retreat” and “bases of supplies.” Let us discard such ideas.… Success and glory are in the advance; disaster and shame lurk in the rear.

Pope also had brought east with him a military style considered unusually harsh. He warned civilians that they would be responsible for “attacks upon trains or straggling soldiers by bands of guerrillas in their neighborhood,” threatening that any home from which shots were fired would be razed and its residents imprisoned, and anyone involved in that type of attack “shall be shot, without awaiting civil process.” He told his commanders that their troops could confiscate whatever food or supplies were needed to successfully prosecute the war if Southern farmers refused to sell to them. He went so far as to threaten that anyone corresponding with a member of the Confederacy, even a family member, could be executed.

His proclamations were signed, pompously, “from headquarters in the saddle,” which caused people to suggest that perhaps his headquarters actually were in his hindquarters.

Lincoln shrewdly did not replace the popular McClellan with Pope; rather, he detached specific units from McClellan’s command and transferred them to the newly created Army of Virginia under Pope.

To the distress of many soldiers, General John Pope’s victory at Island No. 10 caused Lincoln to give him command of the Army of Virginia. “His pompous orders … greatly disgusted his army from the first. … All hated him,” wrote General A. S. Williams, who served on his staf f. Pope held his command for less than six months, being relieved after his defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run.

As much as officers and troops respected McClellan, they grew to despise Pope. Brigadier General Samuel D. Sturgis summed up those feelings quite accurately when he said, “I don’t care for John Pope one pinch of owl dung.” McClellan himself was furious, writing Lincoln that this was a war that should be fought “against armed forces and political organizations. Neither confiscation of property, political executions of persons, territorial organization of states or forcible abolition of slavery should be contemplated for a moment.”

But to Lincoln none of this mattered. Pope said all the right things. He told the president that if ordered he would march directly toward Richmond—even if he had to go through Confederate defenses. His only demand was that Lincoln direct McClellan to attack as soon as Pope’s troops were engaged. This was exactly the kind of audacity Lincoln had been longing to hear from his commanders.

Pope’s Army of Virginia eventually numbered seventy thousand men, bringing together elements from the armies of the Shenandoah Valley, Northern Virginia, and the Potomac. Among the officers placed under his command was General Fitz John Porter, who loathed him, commenting at one time that “Pope could not quote the Ten Commandments without getting ten falsehoods out of them.” Pope intended to attack Lee’s troops from the east while they were fighting McClellan on the peninsula. But as the threat on Richmond from McClellan was blunted, Lee sent generals Stonewall Jackson and A. P. Hill north to Manassas to stop Pope’s advance.

They made contact with Union troops on August 9 at Cedar Mountain. Jackson’s vaunted Stonewall Brigade was taking devastating casualties when Jackson raised his sword and personally rallied his troops. As one eyewitness later wrote, his men “would have followed him into the jaws of death itself; nothing could have stopped them, and nothing did.” Both sides broke off the fighting with nothing settled.

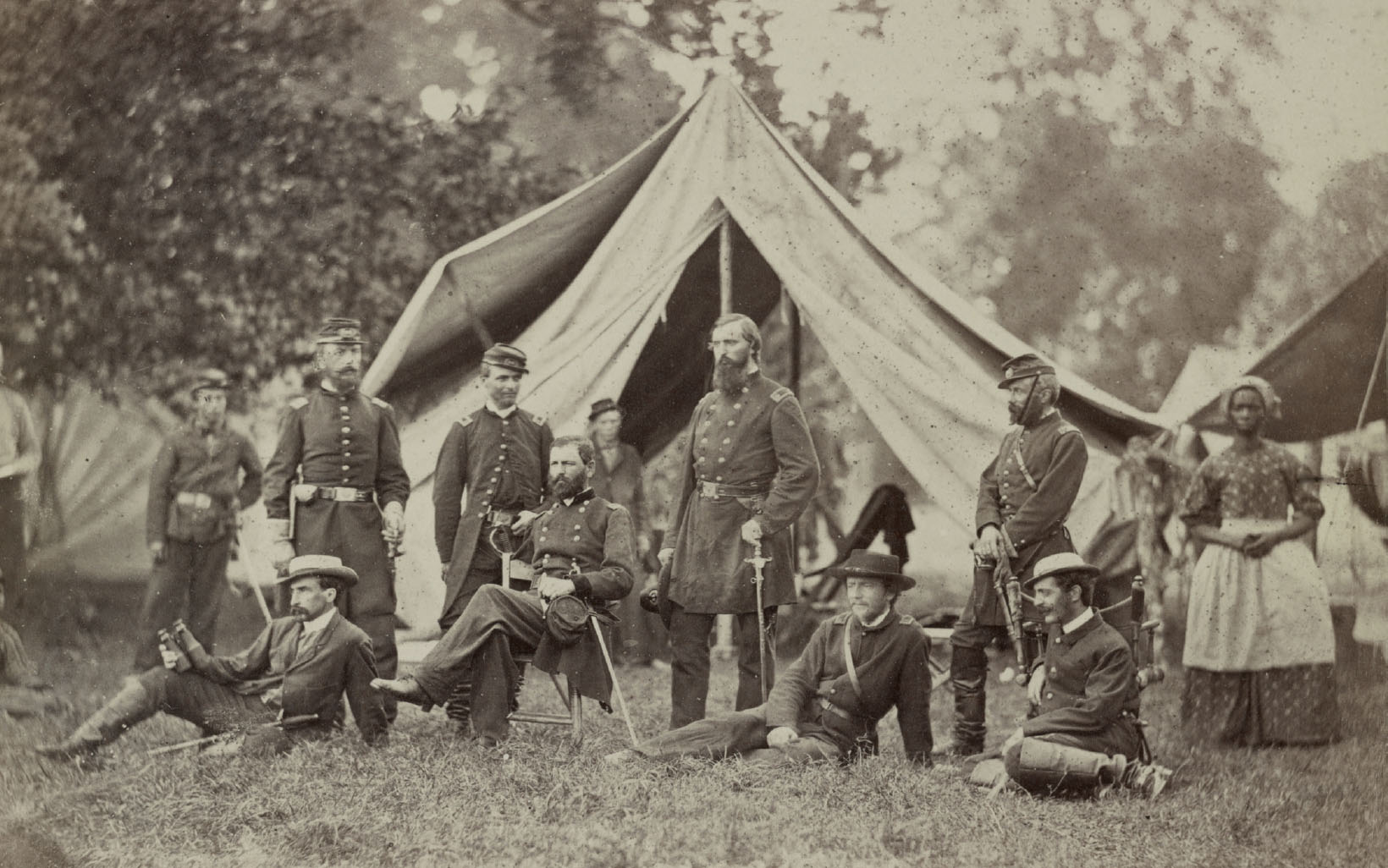

This camp photo of General Fitz John Porter (seated, center) obviously was taken before November 1862. Note the “contraband,” probably former slaves employed by the army to cook and clean. After the Second Battle of Bull Run, Porter was convicted of deliberately disobeying the orders of his commander, John Pope, but decades after the war a commission found that his actions may have saved the Army of Virginia, and an act of Congress restored his commission—and his reputation.

While Pope prepared for a major battle, Lee continued pecking away at him. The two sides sparred over the next few days as they each probed for a weakness. The armies remained in such close quarters that Union cavalry successfully raided Confederate cavalry commander Jeb Stuart’s camp, capturing Stuart’s famed plumed hat—and dispatches from Lee outlining his battle plan. Stuart’s men, meanwhile, raided a federal supply depot at Catlett’s Station, seizing Pope’s dress uniform—and dispatches confirming that reinforcements were on the way to support him.

Lee had little respect for Pope, referring to him disdainfully as a “miscreant” who “must be suppressed.” So he must have taken special delight when his scouts discovered an unguarded crossing beyond Pope’s right flank. Jackson’s 24,000-strong foot cavalry covered fifty-four miles in only thirty-six hours, successfully moving behind the Bull Run Mountains, driving twenty miles deep into the Union rear. His men ripped up railway lines and cut telegraph wires, severing Pope’s supply line and communications with Washington—and then attacked the Union army’s principal supply depot at Manassas Junction.

The supply depot was a hungry army’s dream come true. Jackson’s men feasted on fruit, meat, oysters, and lobster—and hundreds of barrels of liquor. They found wine and whisky, beer and brandy. But just as they started to taste their victory, Jackson ordered the barrels smashed open and the contents dumped, fearing “that whisky more than I do Pope’s army.”

“I shall never forget the scene when this was done,” wrote Major W. Roy Mason. “Streams of spirits ran like water through the sands of Manassas, and the soldiers on hands and knees drank it greedily from the ground as it ran.” But liquor was not the greatest prize.

New York publisher Charles Magnus was one of Currier and Ives’s few rivals. His prints, like this one illustrating the chaos and brutality of the Second Battle of Bull Run, were known for their vivid coloring, often achieved by using uncommon paints stenciled by a line of artists each responsible for only one color.

In addition to food and clothing, the depot contained forty-eight pieces of artillery, ten locomotives, two railway trains loaded with fifty thousand pounds of bacon, twenty thousand barrels of pork, thousands of barrels of flour, clothing, tents—all the stuff of a well-fed and well-equipped army. Wrote another witness, “To see a starving man eating lobster salad and drinking Rhine wine, barefooted and in tatters, was curious. The whole thing was indescribable.” Jackson knew his time there was short, so most of it was burned in a huge bonfire. And then, before the outraged Pope could get there, Jackson’s men slipped away. His three divisions took defensive cover behind an uncompleted railway embankment on the old Bull Run battlefield, which a year later still bore the scars of that fight.

Pope’s army flailed around blindly, unable to find Jackson. Pope was accustomed to fighting traditional battles, but Lee refused to provide a conventional target for him.

As Lee and General James Longstreet rode north to support Jackson’s army before Pope’s much larger force could destroy it, fate once again dictated terms. As they approached Groveton, about thirty-five miles from Manassas, Lee rode forward to get a look at the terrain. Within a few minutes Lee returned, a small cut sliced into his cheek. An aide, Major Charles S. Venable, reported that the general had said quietly, “A Yankee sharpshooter came near killing me just now.”

That sharpshooter had come within an inch of changing history. Lee had escaped death, perhaps because a gust of wind affected the shot, and his calm response only added to his legend. Lee ignored his superficial wound and continued toward Manassas.

The Second Battle of Bull Run—or as it was known in the Confederacy, Second Manassas—began late in the afternoon of August 28, when Jackson’s troops surprised General John Gibbon’s Iron Brigade marching to join Pope, who was utterly confused by Jackson’s tactics. The Iron Brigade was formed by four western regiments, the only all-western brigade in the Army of the Potomac. These well-drilled troops proudly emphasized their distinctiveness by retaining the formal dress black “Hardee” or “Jeff Davis” hat. Whether it was their endless training or pride in their black hats, it worked. When Jackson’s men let loose a rebel yell and swooped down the hillside at Brawner Farm, the Black Hats stood their ground and began pouring fire into the attackers’ lines.

The battle raged into the early evening. Having given up their defensive position on the railway embankment when they launched the attack, Jackson’s outnumbered troops had to fight it out on equal ground. Gibbon, along with a second brigade under General Abner Doubleday, skillfully maneuvered their troops. Eventually the outcome came down to courage and bloodshed. Much of the fight took place at close quarters. As one Union veteran wrote, “The two crowds, they could hardly be called lines, were within, it seemed to me, fifty yards of each other, and they were pouring musketry into each other as rapidly as men could load and shoot.”

After fighting in the Second Battle of Bull Run, Union soldier Robert Knox Sneden drew this map for his personal diary, which was discovered decades later. Sneden was captured and imprisoned at Andersonville but survived, and almost a century later his words and beautiful sketches would bring the war to the public.

Jackson ordered an attack at dusk. As another Union soldier remembered, “Our boys mowed down their ranks like grass; but they closed up and came steadily on.”

In only a few hours of fighting each side had suffered an estimated thirteen hundred casualties. One of every three men were killed or wounded. As the sun fell behind the Bull Run Mountains and the shadows darkened into night, men searched the battlefield for the still living. The dead lay where they fell. At that time there wasn’t much that could be done for wounded soldiers; amputation was the only known means to prevent deadly infections. Because so many men had died for lack of care in the Peninsula Campaign, a rudimentary ambulance corps was in the process of being created; two wagons were to be assigned to each regiment, one to carry medical supplies, the second to transport the wounded to the relative safety of field hospitals. But they were not yet in service and some wounded men would lie in the fields for more than a week before they received care. And this was just the beginning of the carnage.

The placid Potomac River, drawn near Williamsport on the morning General Lee’s army crossed and began its invasion of the North.

It wasn’t until much later in the night that Pope learned about the battle. He was elated, believing Jackson’s twenty-five thousand men were caught between major Union forces. He immediately requested that Lincoln dispatch the reinforcements he had been promised, then ordered his commanders to attack in the morning, telling them, “I do not see how it is possible for Jackson to escape without very heavy loss, if at all.”

McClellan had given up the fight on the peninsula and returned to Washington, allowing Lee and General Longstreet the freedom to turn and march to Manassas. But he resisted Lincoln’s request that he commit his remaining troops to Pope’s battle, arguing that the men were needed to protect Washington. “I do not regard Washington as safe against the rebels,” he wrote to his wife. “If I can quietly slip over there I will send your silver off.”

The armies punished each other brutally for the next two days. The fighting was so intense that some members of the Stonewall Brigade ran out of ammunition—and rather than retreating, they stayed in their position and started throwing rocks at the enemy. On the afternoon of the twenty-ninth, Pope, who did not yet know that Longstreet’s army had arrived, ordered Fitz John Porter to attack Jackson’s right flank. But Porter collided with General James Longstreet and defied that command. Meanwhile General Philip Kearny attacked Jackson’s left flank, ordering his men to “fall in here, you sons of bitches and I’ll make major generals of every one of you!” As one of his men wrote, when they charged forward, “The slope was swept by a hurricane of death, and each minute seemed twenty hours long.” By the morning of the thirtieth a very confident Pope informed Lincoln that he had won a significant victory. Jackson was in retreat, he reported, and he intended to pursue his army and, if possible, destroy it.

But like McClellan, he had fatally underestimated Lee’s cunning. Misguided by poor intelligence and ignoring warnings that the rebels had arrived in force, Pope mistakenly concluded that Lee and Longstreet intended only to provide protection for Jackson’s army as it withdrew. Determined to prevent that retreat, he once again ordered Porter to attack. Reluctantly, Porter formed his column and began his pursuit of Jackson—and marched right into a trap.

Lee had come to Manassas to fight and had played Pope’s tune to perfection. He had shown him what he expected to see, using the man’s own confidence to set him up for the slaughter. Longstreet’s twenty-five thousand men were lying in wait for Porter’s five thousand troops. When the Yankees launched their attack on Jackson, rebel artillery and muskets brought thunder down on them. As one of Longstreet’s men remembered, “The first line of the attacking column looked as if it had been struck by a blast from a tempest and had been blown away.” Porter’s men charged right into their guns, waging a heroic struggle. But against “a perfect hail of bullets,” as Private Alfred Davenport described the scene, they could not sustain the offensive. “We broke and run,” wrote fifteen-year-old William Platt, and “they shot us down by hundreds.”

As the Union line disintegrated, Longstreet’s troops attacked. His men fought through the remnants of Porter’s troops and pressed the attack deep into Pope’s lines. The Johnny Rebs moved forward steadily for almost four hours, creating a relentless hailstorm of bullets and artillery. Longstreet’s batteries could barely keep pace with the infantry and had to continuously move forward after firing only a few shells.

To their credit and honor, the Billy Yanks fought gamely and bravely. They conceded nothing. But when the sun mercifully went down, Pope ordered his men back across Bull Run. As Confederate reports described the scene, “In its first stages the retreat was a wild frenzied rout—the great mass of the enemy moving at a full run, scattering over the fields and trampling upon the dying and the dead in the mad agony of their flight.”

Pope had suffered a humiliating defeat.

The human cost of the war was growing beyond normal comprehension. The Union suffered 13,824 killed, wounded, or missing at Second Bull Run—more in this one battle than the new nation had borne during the entire Revolutionary War. The Confederates lost 8,353 men killed, wounded, or unaccounted. Soldiers who only a year earlier had marched proudly through the main streets of towns and villages, sent off to war to the cheers of men and the swoons of women, were coming home missing arms and legs or too often in wooden boxes.

A war that few people had wanted but no one could prevent was now raging out of control. Some Northern newspapers and Democratic politicians began suggesting that a negotiated settlement with the South might be possible. In fact, in the midterm elections several months later, the Republican Party suffered substantial losses, evidence that the Union was quickly growing weary of the war. The thousands of deaths at Bull Run and subsequent battles had soured the patriotic fervor.

Pope was relieved of his command within a week and ordered to Minnesota to put down a Sioux Indian uprising. He settled blame for his loss partially on Lincoln, whom he called “feeble, cowardly, and shameful,” and McClellan, but mostly on Fitz John Porter, who had refused his order to attack on the first day of the battle. Three months later Porter was arrested and charged with disobeying a lawful order and misconduct. His court-martial was a major news event, as the often bitter rivalries between Union officers that so plagued Lincoln were finally exposed to the public. The court-martial had serious political implications; Democrats wanted to use it to place the blame for the growing disaster on Lincoln and the Republican Party. Porter’s defense contended that Pope was incompetent and argued that by disobeying his order, Porter had actually saved his army. A slew of generals testified, many of them using the opportunity to buttress their own standing. McClellan took the opportunity to once again disparage Pope. But the court-martial, apparently swayed by those political considerations, found Porter guilty and dismissed him from the army. While signing the order ending Porter’s military career, a furious Lincoln said, “In any other country but this, the man would have been shot.”

Mathew Brady’s 1861 studio portrait of thirty-five-year-old general George McClellan, one of the most beloved and controversial figures of the war.

For a nation at war, the verdict proved extremely controversial. Porter was incensed at being branded a traitor and immediately began a campaign to restore his honor. Those people who believed he was guilty claimed he was undermining morale by continuing to attack the army and administration. The New York Times suggested his efforts promoted dissension among the troops, even suggesting that perhaps he should have been executed for his disobedience. But Porter persisted and sixteen years later President Rutherford B. Hayes agreed to permit an investigation. In the prolonged hearing Porter presented maps, telegrams, and numerous witnesses from both armies. The commission finally reported that the court-martial had not had access to the information it needed and that rather than a coward or a traitor, Porter was “obedient, subordinate, faithful, and judicious” and that his actions probably “saved the Union army from disaster on the 29th of August.” Finally, in 1886 he was granted a full pardon by Democratic president Grover Cleveland.

After smashing through Pope’s army Lee once again threatened Washington. In early September 1862, his army crossed the Potomac into Maryland, coming within twenty miles of the Union capital. Lincoln once again handed authority—and the responsibility for stopping Lee—to George McClellan. He did so reluctantly and against the specific wishes of a majority of his cabinet, who handed him a letter stating flatly that they felt strongly that it was “not safe to entrust to Major General McClellan the command of any Army of the United States.” In fact, Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase was infuriated by the decision, believing that McClellan’s failure to send reinforcements to Pope, as had been promised, amounted to treason, and “giving command to him was equivalent to giving Washington to the rebels.”

Lincoln believed he had no choice, responding, “We must use the tools we have.… Unquestionably he has acted badly toward Pope. He wanted him to fail. That is unpardonable. But he is too useful now to sacrifice.” The greatest weapon McClellan possessed was the respect of his troops. He retained their loyalty, having proved to them that he valued their lives far more than many other officers did, some of whom were thought to put their own career ahead of the welfare of their troops. As Lincoln pointed out ruefully, “If he can’t fight himself he excels in making others ready to fight.”

When the defeated and dispirited army learned that McClellan had been returned to command, they responded with wild “huzzahs!” The politicians might despise him, but his men loved him. “The reinstatement of McClellan has inspired strength, vigor, and hope in the army,” wrote Navy Secretary Gideon Welles. McClellan, too, was elated, his contempt for Pope’s ability having been shown to be justified. “Pope has morally killed himself and is relieved of command,” he boasted. “I have done nothing toward this.… I have now the entire confidence of the government and the love of the army. If I defeat the rebels I shall be master of the situation.”

As McClellan began reorganizing the tattered army, the city of Washington prepared for an attack. Clerks and employees in government offices were enlisted to provide support. Gunboats were anchored in the Potomac. The sale of liquor was suspended. Secretary of War Stanton pleaded with Northern governors for more soldiers. Rumors spread quickly. The lack of communications caused many people to reach the darkest conclusion: Lee was marching on Washington.

In fact, Lee had no intention of attacking Washington. He knew his army lacked the strength or firepower to overcome the well-fortified city; in fact, it was, as Lee informed President Davis, “lacking much of the material of war.” His men were in desperate need of food and ammunition and he hoped he might find those supplies in “the fields of Maryland laden with ripening corn and fruit.”

Lee also believed his advancing army might be welcomed by people sympathetic to the Confederate cause. Maryland was a border state in which slavery was legal—and public opinion there was mixed. It was even possible that the presence of his army could spark an uprising. On September 4, Lee’s troops began crossing the Potomac near Leesburg, Virginia, singing the pro-secession, anti-Lincoln song “Maryland, My Maryland” as they climbed up an embankment into Northern territory at White’s Ford. This was the farthest north they had been able to penetrate. But several thousand of the troops, feeling strongly that they had enlisted to defend their homes and not invade the North, simply turned around and went home, while many others straggled behind, lacking shoes and other equipment. Lee was at the front of his army, carried by ambulance. After the battle at Manassas, he had dismounted and was holding Traveller’s reins when the horse was spooked. Traveller had reared, spraining both of Lee’s wrists on a tree stump, preventing him from leading his men from horseback for several months.

As his men marched into Maryland, Lee issued a proclamation calling for an uprising. It read:

The people of the Confederate States … have seen with profound indignation their sister State [Maryland] deprived of every right, and reduced to the condition of a conquered province.… The people of the South have long wished to aid you in throwing off this yoke, to enable you to again enjoy the inalienable rights of free men, and restore independence and sovereignty to your State.… In obedience to this wish, our Army has come among you, and is prepared to assist you with the power of its arms in regaining the rights of which you have been despoiled.… It is for you to decide your destiny, freely and without constraint.

Lee’s call to arms was met mostly with indifference. Western Maryland was an area of small farms with few slaves, and most of the residents who took a stand in the war remained loyal to the United States. Rather than receiving a hero’s welcome, people greeted his invading army with suspicion. A man watching them march into Frederick, Maryland, on September 6 wrote that he was surprised to see “dirty, lank, ugly specimens of humanity, with shocks of hair sticking through holes in their hats, and the dust thick on their dirty faces.” Many residents simply hid their Union flags and stayed inside their homes. But one person did not.

The Confederate arrival in Frederick was immortalized a year later with the publication in the Atlantic Monthly of John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem “Barbara Fritchie,” which relates the supposedly true story of a ninety-year-old woman who defiantly hung out a Union flag when the rebels marched into the city. After its staff was shot down, she picked up the flag and …

She leaned far out on the window-sill,

And shook it forth with a royal will.

“Shoot, if you must, this old gray head,

But spare your country’s flag,” she said.

The poem’s patriotic message—an elderly woman offering her life to protect the American flag—was embraced by Northerners and became such an enduring part of American culture that three silent movies were made about it. During World War II British prime minister Winston Churchill quoted these very lines. While the essence of this legend may be true, the crucial details are disputed. One thing most historians agree upon is that the woman who stood tall against the Confederates wasn’t Barbara Fritchie.

Barbara Fritchie was a slave-owning widow who supported the Union. While she was in Frederick during the invasion of 1862, she apparently was ill; in fact, she would die three months later. But there were several other women who might well have waved a Union flag in the face of the rebels, including schoolteacher Mary Quantrill, whose husband’s uncle formed the notorious gang Quantrill’s Raiders. Quantrill supposedly was waving a small handheld flag; when an officer attempted to take it away, she fought back, and he eventually left her alone, telling her he admired her spirit. The poem also might have referred to seventeen-year-old Nancy Crouse, who lived in Middletown, Maryland. She owned a large flag, and when the soldiers tried to take it away, she apparently wrapped herself in it, although she did surrender it when they threatened her at gunpoint. It could also have been referring to Susan Groff, a Frederick hotelkeeper who had gained renown by hiding ninety rifles in a Main Street well to prevent them from falling into rebel hands, and who owned and often displayed a very large American flag.

The legendary story of ninety-year-old Barbara Fritchie waving a tattered American flag as Stonewall Jackson marched into Frederick was so successfully memorialized by poet John Greenleaf Whittier that sixty years later artist N. C. Wyeth painted his vision of the incident.

Whatever the real story behind the legend is, it is undoubtedly true that the residents of western Maryland offered little cooperation and at least some resistance to Lee. When he offered to buy their farm products, they refused to accept Confederate currency; the farmers wouldn’t pick crops, the millers wouldn’t grind wheat, shopkeepers didn’t open their shops, and cattle owners saved their herds by moving them into Pennsylvania.

By crossing the Potomac into Maryland, Lee had uncorked another complicated problem: what do to about the free blacks living in peace there? The rights of slaves, escaped slaves, and free blacks—and their owners—living in Virginia and Maryland were unsettled and uncertain. Their situation appeared to change depending on which army controlled which territory. Throughout the North, governors and state legislators debated allowing black men to join the armies and fight. But the single greatest unanswered question was what would happen to them, whatever their current status, when one side emerged victorious? It was a question that the leaders on both sides did not want to answer.

Robert E. Lee’s inconsistent conduct regarding the question of slavery exemplified its ongoing complexity. The commander of the Confederate army had said publicly that slavery was abhorrent and yet he held a confusing position about slavery himself. In that same often-quoted letter in which he called slavery immoral, he also wrote that slavery somehow was ordained by God for the slaves’ own future benefit. “The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa. The painful discipline they are undergoing is necessary for their instruction as a race.… How long their subjugation may be necessary is known and ordered by a wise Merciful Providence.”

Native Americans called the beautiful Shenandoah Valley, seen in this 1864 Currier and Ives print, the “Daughter of the Stars.” Its value as a route between north and south for centuries was emphasized during the Civil War, when three major campaigns were fought there.

While Lee owned no slaves in his own name, he and his wife, Mary Custis Lee, inherited slaves from her father, George Washington Parke Custis. But according to a provision in Custis’s will, those slaves were to be set free only after all of his plantation debts had been settled or five years passed. Lee was the administrator of the estate and kept those slaves in bondage to try to save the plantation. In 1859, three of those slaves, Wesley Norris, his sister Mary, and his cousin, believing they had been promised their freedom after Custis’s death, escaped and were caught at the Pennsylvania border. What happened next has long been debated. According to an account given by Norris to the National Anti-Slavery Standard in 1866, they were returned to Arlington, where Lee ordered the men to receive fifty lashes and Mary Norris twenty lashes. When the overseer refused, Lee recruited the county constable to carry out the punishment. Norris claimed that “General Lee … stood by, and frequently enjoined Williams [the constable] to ‘lay it on well,’ an injunction which he did not fail to heed; not satisfied with simply lacerating our naked flesh, General Lee then ordered the overseer to thoroughly wash our backs with brine, which was done.”

An anonymous letter that was published in the New-York Tribune in June 1859 about the incident went further, claiming that Lee himself actually had put the whip to Mary Norris. Lee eventually denied the entire story, stating, “There is not a word of truth in it.” There isn’t sufficient evidence to determine what really happened that day. But an even more confusing footnote to the story is that on January 3, 1863, two days after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in the North, Lee legally declared that Custis’s slaves were “forever set free from slavery.”

Historians have never been able to agree on Lee’s motivations, but the general certainly must have been aware that a Confederate victory, or even a negotiated settlement, would mean that slavery would continue to exist and might even be extended to new states and territories. And when his army marched into Maryland, the prospect of victory had never been more real. Lincoln’s Army of the Potomac was reeling, and cities as far up the coast as New York were watching Lee with great anxiety. In the west, Confederate troops had occupied Lexington, Kentucky, and were pressuring Louisville and Cincinnati with the goal of enlisting Kentucky in the cause—either by choice or by force. While Lee did not believe an attack on Washington was feasible—at least not at this time—he certainly planned to carry his campaign into Pennsylvania in hopes that people might despair of fighting and elect a Democratic Congress disposed to ending the war with a treaty that recognized the rights of Southern states to self-determination. Finally, he wanted Britain to recognize the Confederacy as an independent nation.

British manufacturers were growing desperate for Southern cotton and the large markets cut off by the Union blockade. The sticky issue of slavery was standing in the way of profit. These cautious English politicians simply needed a little bit more assurance that the Confederacy could continue to dominate the larger Yankee forces. A few more impressive victories like Second Bull Run would ensure recognition and with it a demand that Lincoln accept British mediation to end the war.

Disappointed at the inability of his army to survive by foraging, Lee knew he had to secure his lines of supply and communications from the Shenandoah Valley. To accomplish that he once again split his forces, dispatching Stonewall Jackson to attack and capture Harpers Ferry, which was defended by about twelve thousand federal troops. The army would reunite at Boonsboro after achieving its objectives. Although splitting his already weakened army was a dangerous gamble, Lee was certain that the always cautious McClellan wouldn’t dare leave Washington poorly defended.

But once again, fate played an unexpected hand. Lee had prepared three copies of his top secret Special Order No. 191 to be delivered to his generals. These plans included the routes to be taken by each force and the timing of the attack on Harpers Ferry. “The army will resume its march tomorrow,” it read. Then he outlined precisely what he expected of his commanders—for example, “General McLaws … will take the route to Harpers Ferry, and by Friday morning possess himself of the Maryland Heights and endeavor to capture the enemy at Harpers Ferry and vicinity.” They were each signed by Lee’s adjutant, General R. H. Chilton.

One general who received the order pinned it securely to an inside pocket. Longstreet memorized his copy, then reportedly chewed it up. Major General Daniel H. Hill, Jackson’s rear guard commander, also received a copy. On the morning of September 13, Union corporal Barton W. Mitchell of the 27th Indiana Volunteers was walking around a campsite just outside Frederick that rebel troops had recently abandoned. He spotted a thick envelope the rebels had lost or left behind. Inside he found three cigars wrapped in paper—and was stunned as he began reading it. Mitchell handed it to Sergeant John W. Bloss, who sent it forward through the chain of command until it reached headquarters. Incredibly, one of the adjutants at headquarters, Samuel E. Pittman, had worked in a Detroit bank when Chilton was the paymaster at a nearby army post—and recognized his signature.

McClellan had been handed Robert E. Lee’s secret plans. If he moved quickly and struck firmly, he might drive a stake through the heart of the Confederate army. The outcome of the war could be determined in the next few days if he found the courage.

If.

In some ways, the Civil War was the first modern war, giving the world a view of the terrifying weapons of the future.

The Gatling gun, the forerunner of the machine gun, was capable of firing several hundred bullets a minute. Patented in 1862, it was used for the first time in battle during the 1864 siege of Petersburg.

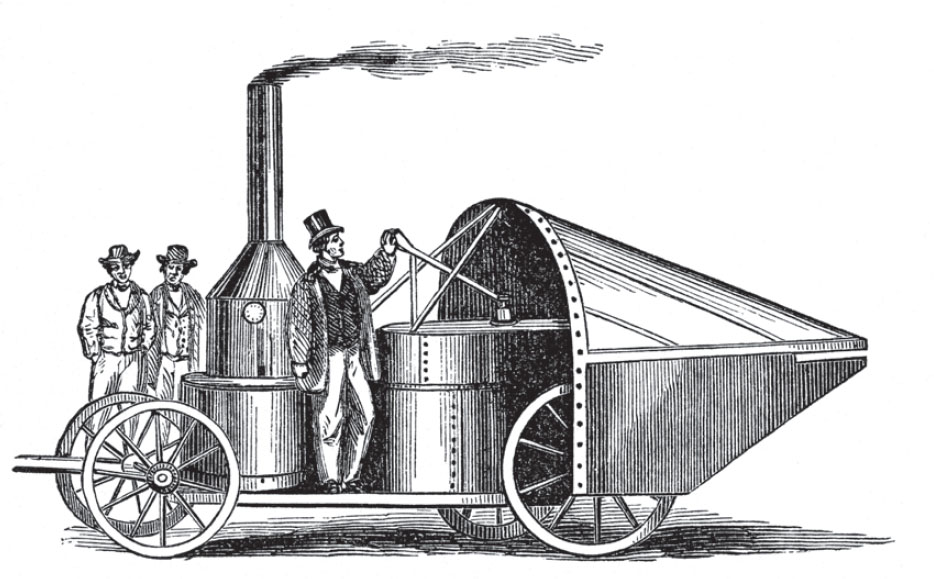

Among the early attempts to adapt technology to weaponry was the Winan’s Steam Gun, a mounted gun about the size of a steam engine that used centrifugal force rather than gunpowder to fire about 250 rounds a minute.

The Union made a further attempt to adapt this protective technology by building an ironclad battery equipped with 18-cannons. This 700-foot long floating fort, which would be moved by steam engines, was still being built when the war ended.

Ironclad warships were used in battle for the first time on March 9, 1862, at the Battle of Hampton Roads when the Union Monitor and the Confederate Merrimac, carrying traditional cannon, fought to a draw.

The Confederacy experimented with contact mines, known as “torpedoes.” Surprisingly, inventor Robert Fulton had pioneered development of these devices, which were considered unethical. For a time, even the rebels banned their use. The rebel torpedo at right was anchored in the Tennessee River. Confederate torpedoes proved very successful, sinking and damaging numerous Union vessels.

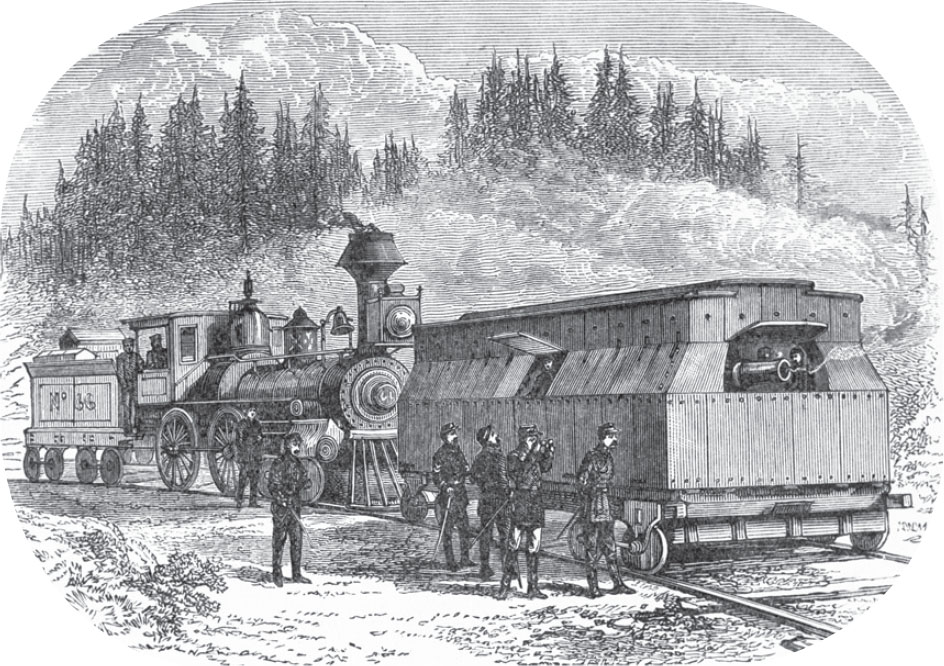

After iron- or steel-clad ships proved their value, an attempt was made to extend the concept to the railroads; “Railroad Monitors,” as they were known, were described as “iron-clad railroad batteries,” and proved effective in limited use.