Before the nation fell into war and when it was still being cobbled together state by state, the vast Texas territory was the great prize. The Republic of Texas had declared its independence in 1836, but the Mexican government had refused to acknowledge it. After Mexico rejected an offer from President James K. Polk to purchase the sparsely occupied land between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande in 1845, General Zachary Taylor led American troops into the disputed territory of Coahuila and the Mexican-American War began. In 1847, General Winfield Scott led the first major amphibious landing in American military history, preparing to attack the city of Veracruz. Within months Scott’s army was closing in on the Mexican capital, Mexico City.

For many young American soldiers this was to be the great testing ground, the place where they would earn their spurs for the great war they could not know was coming. Among them were Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, George Meade, James Longstreet, and a brand-new West Point graduate, twenty-two-year-old Second Lieutenant Thomas J. Jackson. Initially, Jackson was attached to a rear-echelon artillery battery and his prospects for combat were slim. “I envy you men who have been in battle,” he confessed to a soldier who had seen action. “How I should like to be in one battle.”

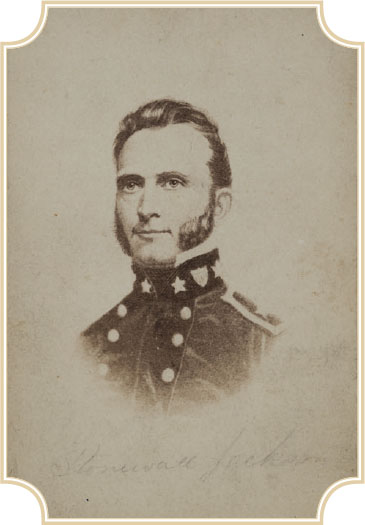

Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson was second only to Robert E. Lee in the hearts of Confederates. Historians consider him among the most gifted leaders in American military history, and his accidental shooting by his own men changed the course of the Civil War.

That opportunity finally came during the September 1847 battle for control of Chapultepec Castle, a key point in Mexico City. Ordered to provide artillery support for infantry troops attacking Chapultepec Castle, Jackson’s unit struggled to drag their guns across the marshy land that surrounded it. Mexican troops occupying the castle heights raked fire down on the American attackers. Artillery began shelling them. One of Jackson’s guns was hit and three men were killed. As his men began breaking, diving for cover, and retreating, Jackson stood tall and defiant. When he was asked about being in battle for the first time, he responded that he had been “afraid the fire would not be hot enough for me to distinguish myself.”

It was at this moment that the legend that was to become Stonewall Jackson was born. Supposedly a Mexican cannonball shot right between his legs. Rather than panicking, he looked down disdainfully, as if insulted that death had come so close. He attempted to rally his men with the cry, “There is no danger! You see! I am not hit!” When that failed, when fear and blood proved too much for most of the men and they cowered on the ground, Jackson and one sergeant loaded and fired the fieldpiece, and then did it again. Later, a second American cannon was pulled into position and opened fire. Eventually, the overwhelming American force was able to take the castle—and Tom Jackson emerged from the smoke of battle as a courageous battle-hardened officer. For his gallant and meritorious service in battle he was promoted to the rank of brevet, or temporary, major.

Lieutenant Jackson first gained notoriety during the storming of Chapultepec Castle in the Mexican-American War when he refused an order to withdraw and instead created an opening that reinforcements successfully exploited.

That’s the way the story was told and it brought great attention to the young officer. According to legend, there was one other event during that war that would play an important role in the War Between the States. It was during the Mexican-American War that Tom Jackson befriended Captain Robert E. Lee. In fact, the two men formed such a fast friendship that when Lee responded to a slight by another officer by challenging him to a duel, he asked Jackson to serve as one of his seconds. The first shot was rifles at forty paces—and both Lee and his opponent missed. Lee’s opponent then retired and the matter of honor was considered settled; but Lee and Jackson had forged the bond of complete trust that would make a difference years later.

In addition to being a fearless warrior, Stonewall Jackson was a devout Christian, a Calvinist who believed God had planned his fate, which meant he could take great risks because the outcome was already determined. Whether he lived or died was God’s will, and therefore standing or hiding in battle made no difference. “My religious belief teaches me to feel as safe in battle as in bed. God fixed a time for my death. I do not concern myself about that, but to be always ready, no matter when it may overtake me.”

Initially Jackson was not a supporter of secession. “It seems to me, that if they would unite thus in prayer, war might be prevented and peace restored.” And when asked by a friend how he could remain so calm when facing battle, he explained that he found comfort in his faith. “Why should the peace of a true Christian be disturbed by anything which man can do unto him? Has not God promised to make all things work together for good to those who love him?”

When war came in 1861, Jackson, like so many others, was torn between his country and his state. He was born in Clarksburg, Virginia, but his first wife had been born in the North, and his sister was a Unionist, so he spent considerable time in prayer and contemplation before committing himself to the Confederate cause. Believing that the Lord had put him on this path, he never again doubted the righteousness of it. He resigned his teaching position at the Virginia Military Institute and joined Lee’s army. This was the war for which he had been preparing his entire life.

Both Jackson’s sister and father had died of typhoid while he was still a young child and he was raised by an uncle. He was a big man, bulky, and at six feet considerably taller than most men in that era. He was not especially graceful and was said to be an awkward rider. His rural western Virginia upbringing did not adequately prepare him for the advanced studies at West Point and initially he fell behind his younger and far better educated classmates, such as George McClellan and A. P. Hill. At times wealthier classmates ridiculed him for his lower-class background. But the tenacity that was to mark his command in battle quickly became evident and he did whatever was necessary to succeed. As one of his classmates later remembered, “All lights were put out at Taps, and just before the signal he would pile up his grate with anthracite coal, and, lying prone before it on the floor, would work away at his lessons by the glare of the fire.” He graduated in 1846 near the top of his class. One classmate remarked, “There was no one of our class who more absolutely possessed the respect and confidence of all.”

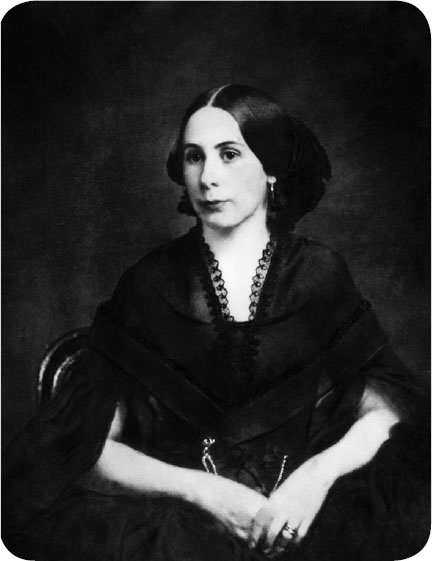

Cartes de visite, or visiting cards, predecessors of calling cards, became extremely popular in the 1850s. This carte depicts a younger and stern pre-Stonewall, Thomas Jackson. This same image was used in 1863 on a deck of playing cards—Jackson was the four of clubs.

After the Mexican-American War was won, rather than serving in a peacetime army Jackson accepted a position at the esteemed Virginia Military Institute, teaching natural and experimental philosophy—which essentially was physics—and artillery tactics. He was not a gifted teacher; his classroom technique consisted of forcing his students to memorize material and recite it precisely as it was written; his tactics course apparently consisted primarily of his students pulling fieldpieces around the campus. He was thoroughly disliked by many of his students. One of them supposedly challenged him to a duel, and he had restraining orders placed on several others. The institute’s superintendent admitted that the man whom students derisively nicknamed Old Jack, Tom Fool, and Square Box, “was no teacher, and he lacked the tact required for getting along with his classes.”

In his classroom he would sit “perfectly erect and motionless,” remembered one of his students, and when he was asked to explain a complex proposition he would recite from his photographic memory the exact words written in the text. He sucked on lemons and at night he was said to sleep with one arm in the air, which he explained increased circulation.

But there also was something so decent about Jackson that even with these quirks, many students admired him. He might not have been a great teacher, but he was a rare leader. And it simply wasn’t possible to ever assume his position on an issue. When VMI’s superintendent, Francis Smith, was put in charge of John Brown’s hanging, Smith assigned several of his students to provide additional security. Jackson was given twenty-one cadets and two howitzers and was only feet away from Brown as he stood on the scaffold. “It was an imposing but very solemn scene,” he wrote to his wife. “I was much impressed with the thought that before me stood a man, in the full vigor of health, who must in a few minutes be in eternity. I sent up a petition that he might be saved. Awful was the thought that he might in a few minutes receive the sentence.”

When the war began, several of Jackson’s students followed him into the Confederate army and served proudly under his command as he rose in prestige. They were with him on the field at Bull Run when he stood resolute while the lines around him were crumbling—the day he became Stonewall Jackson.

No one ever doubted his courage under fire or his mastery of battlefield strategy. Although he was a harsh disciplinarian, his troops loved him. Whenever he or Lee appeared on a battlefield, the men would start cheering; after several such outbursts federal soldiers finally figured out why. From then on, when they heard the hurrahs being raised they immediately began shelling that part of the line. In response Jackson taught his battle horse, the famed Little Sorrel, to run down the line as fast as she could.

It was after the first fight at Bull Run that Jackson pleaded with President Jefferson Davis to carry the war into the North. Captain Edward Porter Alexander reported in his memoirs that when Davis visited the battlefield only hours after the battle had ended, Jackson shouted to him, “We have whipped them. They ran like sheep. Give me 5,000 fresh men, and I will be in Washington City tomorrow morning.”

While President Davis and General Jackson enjoyed a cordial and respectful relationship, Jackson was frustrated by Davis’s reluctance to press forward when he had the Union troops on the run. For him, there was only one way to wage war: “War means fighting,” he once said. “To fight is the duty of a soldier; march swiftly, strike the foe with all your strength, and take away from him everything you can. Injure him in every possible way, and do it quickly.”

The daily life of soldiers at war was brought home to readers through the sketches of Edwin Forbes, which appeared regularly in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. A closer look at this seemingly tranquil scene, Officers and Soldiers on the Battlefield of the Second Bull Run, Recognizing the Remains of Their Comrades, reveals a patrol examining the skulls and bones of the men who died there a year earlier.

Within days of the great Confederate victory at Bull Run, Jackson presented Davis with a strategy that he believed could end the war quickly. McClellan’s army had suffered a grievous defeat, Jackson said, and before he had time to heal his wounds and reinforce his army, the Confederacy had to attack. As General Gustavus W. Smith recalled him proposing,

McClellan’s raw recruits could not stand against us in the field. Crossing the Upper Potomac, occupying Baltimore, and taking possession of Maryland, we could cut off the communications of Washington, force the Federal Government to abandon the capital, beat McClellan’s army if it came out against us in the open country, destroy industrial establishments wherever we found them, break up the lines of interior commercial intercourse, close the coal mines, seize and, if necessary, destroy the manufactories and commerce of Philadelphia, and of other large cities within our reach; take and hold the narrow neck of country between Pittsburgh and Lake Erie; subsist mainly on the country we traverse, and making unremitting war amidst their homes, force the people of the North to understand what it will cost them to hold the South in the Union at the bayonet’s point.

Jackson’s aggressive strategy, which was remarkably similar to the “scorched earth policy” adopted three years later by Union general William T. Sherman as he marched through Georgia, meant declaring war on the people of the region rather than their army. It meant destroying their homes and farms, stores and factories, robbing the enemy of any means of support. Many historians believe that, had it been implemented at that moment, it might have led to a Confederate victory.

But President Davis did not agree with Jackson. Davis wanted to fight a defensive war, confident that as European mills grew desperate for cotton, their governments would intervene to forge a truce, or that the cost of the war would simply be more than the North was willing to bear. The risk of sending his army north without sufficient supplies was far too great for him and he dismissed Jackson’s plan.

Jackson returned to the battlefield, frustrated that his commanders could not see the obvious. His firm belief that he was simply carrying out God’s plans for him allowed him to accept this rebuff. Besides, General Lee also had plans for him. George McClellan had spent the months following his defeat at Bull Run rebuilding his army. Lincoln’s three-month volunteers had been replaced by three-year enlistees. Finally, in the spring of 1862, McClellan was ready to move on Richmond. He launched his Peninsula Campaign by landing troops at Fort Monroe, planning to advance on the Confederate capital from the southeast while McDowell’s thirty-five-thousand-man army was to attack from the north. To meet that threat, Lee ordered Jackson to take seventeen thousand men into the strategically vital Shenandoah Valley, which stretches for two hundred miles between the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountain ranges and at most points is about twenty-five miles wide, to meet McDowell.

But Jackson had far more ambitious ideas. He intended to get to the Big Valley, as it was known, before the federal troops could get comfortable, fight through them, and march on Washington. He executed his plan and reached the Shenandoah Valley undetected and launched a surprise attack on General Nathaniel P. Banks’s six-thousand-man force, at that time the bulk of the Union forces in the region. Only a skillful retreat under fire by Banks prevented Jackson from annihilating his troops. To meet Jackson’s threat, Lincoln immediately ordered McDowell to lay “aside for the present the movement on Richmond … to capture the forces of Jackson and Ewell.”

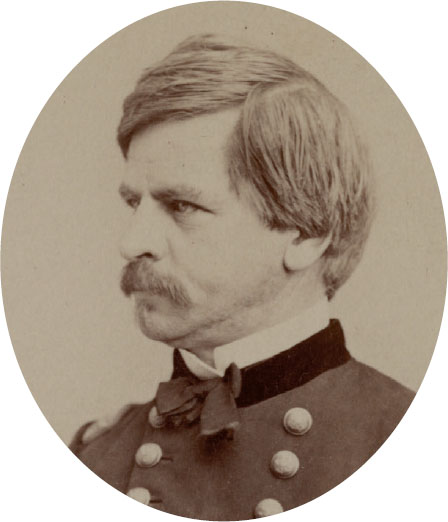

General Nathaniel P. Banks was the perfect example of a politician at war. Lincoln appointed the powerful former Speaker of the House of Representatives and governor of Massachusetts a major general, and his lack of military experience proved telling in a series of lackluster campaigns. He was criticized for failing to reinforce Grant at Vicksburg and later for being unable to occupy Texas in the Red River campaign.

Jackson had successfully taken the pressure off Richmond and instead put it on Washington. As Secretary of War Stanton warned, “Intelligence from various quarters leaves no doubt that the enemy, in great force, are marching on Washington.”

Even from a Union standpoint, McClellan’s failure to capture Richmond might indeed have been “God’s plan.” As John S. C. Abbott noted in his history of the Civil War, “there are innumerable instances, in the history of this war, in which apparent disasters have proved our choicest blessings. Had Richmond then been taken and the rebel army crushed, it is almost certain that some compromise would have been effected which would have preserved slavery, the fruitful cause of all our troubles.”

The truth was that nobody really knew where Jackson’s army was at any specific time. His ability to inspire his men to seemingly incredible feats was already inspiring awe. Jackson’s army, his “foot cavalry,” covered more territory in a day than McClellan’s army could manage in a week. He seemed to be everywhere at once. Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley campaign began in late March, when his men marched out of Winchester, a prosperous town with gaslit streets that had the misfortune to be set on a natural road in the northern valley, surrounded on all sides by small hills that hid the approach of enemy soldiers. It was seventy miles from Washington and twenty miles from the rail depot at Harpers Ferry, making it strategically important. While few local farmers owned slaves and most residents were against secession, when the fighting started the town supplied four companies of men to the Stonewall Brigade. Throughout the war the town changed hands seventy-two different times. Union troops occupied it for the first time in March when Jackson retreated after the First Battle of Kernstown, only to withdraw two months later when Jackson’s reinforced army stormed over those hills from the south. The townspeople were so thrilled to be liberated that many of them joined the Confederate soldiers in fighting the Yankees; one report even described a woman leaning out a second-story window to fire at retreating Union soldiers. Jackson wrote to his wife that the townspeople “seemed nearly frantic with joy.… Our entrance into Winchester was one of the most stirring scenes of my life.” Townspeople besieged him for his autograph on books or on slips of paper, and with his permission cut the buttons off his uniform—but he refused to allow them to cut a single strand of his thinning hair.

Jackson’s strategy of relentless attack, then rapid withdrawal, confounded Union generals, many of whom had studied traditional military strategy at West Point. At one point at the end of March 1862, John Worsham, a proud member of Jackson’s foot cavalry, wrote, “We were now retreating and advancing at the same time, a condition an army never undertook before.” At one point a back road on which they were traveling had become soft with rain and snow, and, “as an evidence of General Jackson’s anxiety and solicitude, I saw him personally getting rocks, and putting them in the holes of this road.”

Somehow Jackson had figured out how to hide thousands of soldiers and his supply train in plain sight, moving throughout the valley at will, striking where he was unexpected, pressuring the bluecoats. On May 23, Worsham recalled, “General Jackson, as usual, made an immediate attack on the enemy.… The Yanks, finding things getting so hot, set fire to the two bridges, and were immediately charged by our cavalry and skirmishers, who saved the bridges in a damaged condition, crossed and were right in the midst of the enemy, Jackson along with them. The enemy made a bold stand and fought well, but they could not withstand Jackson’s mode of warfare, and retreated … soon the entire force was killed and captured.” The next morning, as Jackson’s men marched out of the town, one prisoner shouted out a greeting to a soldier—to everyone’s surprise it turned out to be his brother.

John Esten Cooke, a novelist serving in the Confederate army who filed stories with Southern newspapers, wrote about the love and respect that Stonewall Jackson’s men held for him. In early August, Jackson’s men were entrenched in the thick woods of Cedar Mountain, a small rise known sometimes, and appropriately, as Slaughter Mountain. As Union troops crossed a spacious wheat field, Jackson’s artillery opened up on them with crushing fire. The Union troops’ only possible salvation was to charge directly into the cannons. With loud cheers they raced into the woods and attacked with their bayonets, succeeding in collapsing the Confederate left flank and threatening the main body. Suddenly, Cooke wrote,

At this moment of disaster and impending ruin, Jackson appeared, amid the clouds of smoke, and his voice was heard rising above the uproar and the thunder of the guns. The man, ordinarily so cool, silent and deliberate, was now mastered by the genius of battle.… Galloping to the front amid the heavy fire directed upon his disordered line—with his eyes flashing, his face flushed, his voice rising and ringing like a clarion on every ear, he rallied the confused troops and brought them into line. At the same moment the old Stonewall Brigade and Branch’s Brigade advanced at a double-quick, and shouting “Stonewall Jackson! Stonewall Jackson!” the men poured a galling fire into the Federal lines. The presence of Jackson, leading them in person, seemed to produce an indescribable influence on the troops, and, as he rode to and fro, amid the smoke, encouraging the troops, they greeted him with resounding cheers.

Both sides absorbed as many as three hundred casualties and claimed victory, but the next morning it was reported, “After looking at each other defiantly for a short time,” both armies retired from the field without a clear victor.

Jackson had earned General Lee’s trust while becoming a Confederate hero. By September, Lee had marched his army across the Potomac into Maryland. But his supply route and lines of communications through the Big Valley were blocked by fourteen thousand Union troops in Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg. This was when he devised his plan revealed by Special Orders No. 191, in which he would temporarily split his army, sending Jackson to spearhead the attack on Harpers Ferry.

It was a complicated strategy. Jackson would command three columns that would have to traverse rough terrain—including recrossing the Potomac—to simultaneously approach Harpers Ferry. Success required an unusual degree of communication, coordination, and perseverance. Union troops were well fortified and resisted the initial heavy barrage, but under the cloak of eleven hours of darkness Jackson repositioned his men and guns. Cannons had been dragged up a mountain. At dawn more than five thousand infantrymen and twenty cannons overlooked Harpers Ferry and more artillery pieces were positioned to fire at point-blank range into the ravines where Union troops had taken cover. The Yankees were forced to surrender. At a cost of 273 casualties, Jackson had captured 12,700 prisoners, seventy-three artillery pieces, and two hundred wagons loaded with supplies. It was to be the most complete victory of the entire war.

Following this great victory, Jackson notified President Davis in Richmond, “Through God’s blessing the advance … has been successful.” His belief that all was preordained never wavered. Watching his men leave the field after defeating Union troops in the Battle of Port Royal, he exclaimed, “He who does not see the hand of God in this is blind, sir, blind!” And following his victory at First Bull Run, he had written to his wife, “Whilst great credit is due to other parts of our gallant army, God made my brigade more instrumental than any other in repulsing the main attack.”

By this time Jackson rivaled only Lee as the most admired and beloved Confederate commander. Stories were told about him, some true, many fanciful. For example, it was said that Stonewall was a man of simple tastes who did not imbibe. Yet one cold night during the Shenandoah Valley campaign, when he could not light a fire because the enemy was too close, a staff surgeon, Hunter McGuire, gave him a slug of whisky to warm his insides. “Isn’t the whisky good?” McGuire asked. “Yes, very, I like it,” the general replied, “and that’s the reason I don’t drink it!” Poems and songs were written about him. When he rode through towns the citizens would run to get a glimpse of him, to be able to say they had seen Stonewall Jackson. A poem written about the Shenandoah Valley campaign, “Stonewall Jackson’s Way,” was set to music and became among the most popular songs of the war. Although the publisher originally claimed it was found “written on a small piece of paper, all stained with blood, in the bosom of a dead soldier” long after the war, Northerner John Williamson Palmer claimed credit. The song concludes:

Ah! Maiden, wait and watch and yearn

For news of Jackson’s band!

Ah! Widow, read, with eyes that burn,

That ring upon thy hand;

Ah! Wife, sew on, pray on, hope on;

Thy life shall not be all forlorn

The foe had better ne’er been born

That gets in “Stonewall’s way.”

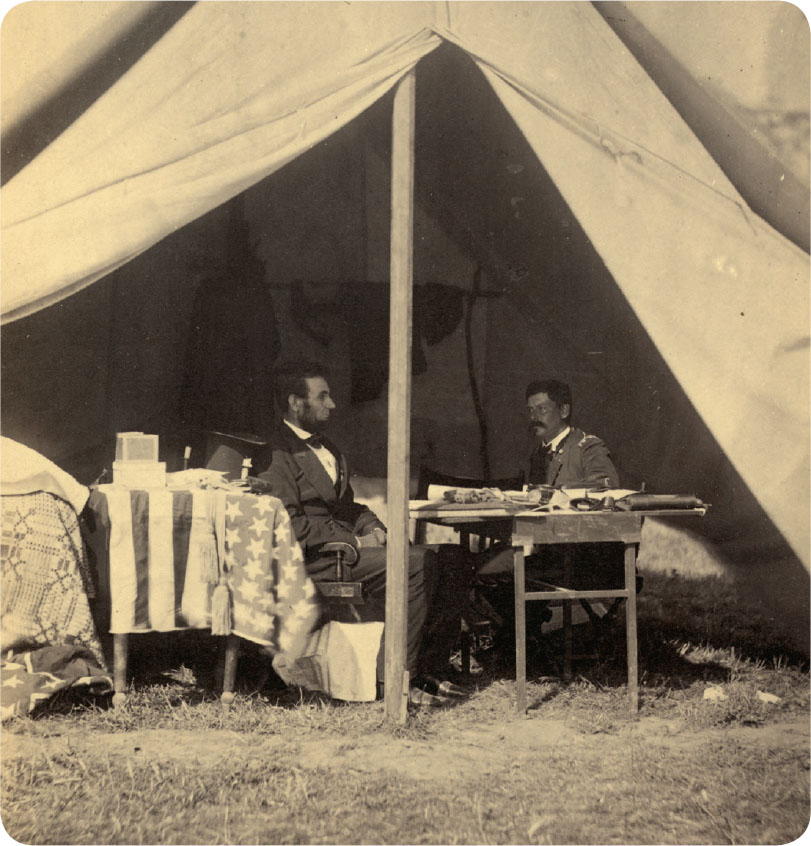

Lincoln and General McClellan, shown at Antietam in this 1862 photo, had a difficult relationship. In the first years of fighting, McClellan’s plodding ways saved countless lives and made him very popular with the Army of the Potomac. But he made no ef fort to disguise his anti-Lincoln politics and resisted the president’s insistence that he move more aggressively.

By late fall 1862, Lincoln finally was done with McClellan. “He’s got the slows,” was the way he described it. McClellan’s failure to pursue Lee’s wounded army after Antietam had convinced the president he would not prosecute the war. Lincoln visited McClellan’s camp with his aide Ozias Hatch, who later recalled, “The President, waving his hand towards the scene before us, and leaning towards me, said in an almost whispering voice: ‘Hatch—Hatch, what is all this?’ ‘Why, Mr. Lincoln,’ said I, ‘this is the Army of the Potomac.’ He hesitated a moment, and then, straightening up, said in a louder tone: ‘No, Hatch, no. This is General McClellan’s body-guard.’”

Historian Stephen Sears wrote that the flawed General McClellan “was a man possessed by demons and delusions.… He believed with equal conviction that enemies at the head of his own government conspired to see him and his army defeated so as to carry out their traitorous purposes. He believed himself to be God’s chosen instrument for saving the Union. When he lost the courage to fight, as he did in every battle, he believed he was preserving his army to fight the next time on another and better day.”

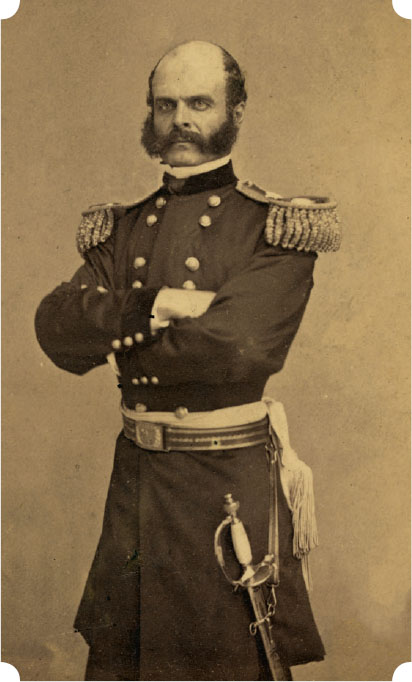

Following the early November elections, in which Lincoln’s Republicans suffered substantial losses in Congress, the president placed General Ambrose Burnside in command of the Army of the Potomac. Burnside, who was easily recognizable by his unusual facial hair, which gave us the word “sideburns,” in fact was a well-respected officer who had won praise for his aggressive tactics at Antietam. He was, as Harper’s Weekly described him, “a soldier who to the greatest military skill unites dash, energy, and the prestige of success, and a man of the most exalted character and the noblest heart.” Far more important to Lincoln was his willingness to fight. The preliminary Emancipation Proclamation had been issued and the president hoped to sign it in January following a great Union victory. He needed that victory to silence his political critics and expected Burnside to deliver it to him.

General Ambrose Burnside (photo, above), remembered as much for giving us the word “sideburns” to describe muttonchops as for his wartime achievements, led his men into Lee’s trap in the Battle of Fredericksburg (above). Concealed Confederate artillery began shelling exposed Union troops, prompting rebel colonel Porter Alexander to later say, “A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it.”

This highly dramatized lithograph, published in 1888, illustrates the difficulty Burnside faced trying to construct pontoon bridges to get his men across the Rappahannock River under withering enemy sniper fire.

Burnside launched an audacious plan: Lee had retreated across the Rappahannock River, near the town of Fredericksburg. That town was sixty miles from Richmond, connected to it by rail and roadway. Burnside proposed smashing through Lee’s lines and marching on the Confederate capital. Lee’s army was spread out in a semicircle about seven miles long. A frontal assault on the main body meant passing between General Longstreet’s five divisions situated west of the town and Jackson’s four divisions in the hills to the south. Instead Burnside decided to attack the flanks, committing sufficient troops to keep Longstreet occupied while launching his real attack on Jackson. Speed was essential; Burnside had to get his men across the Rappahannock on pontoon bridges before Lee discovered the point of his attack and shifted troops to reinforce Jackson.

On November 21, Burnside’s 106,000-man army moved into position. Lee’s 65,000 men lay camped on the Rappahannock, still unsure about the Union intentions. But the pontoon bridges Burnside needed to cross the river were delayed in arriving, and when they finally got there a massive snowstorm made operations impossible. Any chance of surprise was lost. Burnside’s original plan was no longer viable, but he stubbornly refused to alter it to fit the new situation. The delay gave Lee sufficient time to move his troops into strong defensive positions in the hills. As Abbott wrote, “[Burnside’s] success would have been entire, except for the unexpected delay in building the bridges, which gave the enemy ample time to concentrate their whole force at the precise point where it would be most effective.”

The result was a shooting gallery. As the morning fog lifted on December 11, rebel snipers were firing from inside buildings, behind trees and walls. They “laugh[ed] at us with impunity,” remembered a survivor. It took twelve hours before Union troops were able to row two hundred yards across the river and silence the snipers. That was sufficient time for Lee’s army to dig into the hills surrounding the town. They took their strong defensive positions—and then they waited.

Burnside’s army swept into the deserted town of Fredericksburg. The rebel artillery was oddly silent. Union soldiers suspected that Lee was low on ammunition or that he had ordered a withdrawal. In fact, Burnside’s troops were walking into a trap.

At one point Lee considered surprising Burnside by attacking at night, an extremely risky strategy. Among his fears, he confessed, was the difficulty his men would have in identifying enemy soldiers in the dark. Jackson suggested a simple answer: “Strip our men to the waist, and kill every man that has a shirt on.” When Lee rejected that idea, Jackson suggested tying a yard of white bandage around each soldier’s arm. Lee finally decided the night attack was too risky and abandoned it.

Later that afternoon General Lee stood on the top of a rise with Jackson and Longstreet, watching massive numbers of Union troops crossing the river. Longstreet finally asked Jackson, “General, do not all these multitudes of Federals frighten you?”

Jackson answered confidently, “We shall see very soon whether I shall not frighten them.”

A thick fog on the morning of the thirteenth prevented Burnside from launching observation balloons, so he had no idea that Stonewall Jackson was watching every movement. Jackson’s men waited until the Yankees began crossing the half mile of open corn and wheat fields between Fredericksburg and the hills. And then they opened fire.

Entrenched in strongly fortified positions, many of them behind a stone wall, Lee’s troops had a clear field of fire. Burnside fed his men into the grinder, launching wave after wave of frontal assaults that had little chance of succeeding. As General Longstreet respectfully described them, “A series of braver, more desperate charges than those hurled against the troops in the sunken road was never known and the piles and cross-piles of dead marked a field such as I have never saw before or since.”

For a brief time, Union General George Meade’s troops had managed to break through Jackson’s line and threatened to roll up his forces, but Jackson calmly ordered his reserve into the gap and, when Union reinforcements failed to arrive, Meade withdrew.

Burnside’s army paid for every foot they gained with their bodies. By the end of the day they had advanced only five hundred yards. The blood-soaked fields of Mannsfield Plantation would become known forever as the Slaughter Pens and five heroic Union soldiers would earn the Congressional Medal of Honor. More troops fought that day than in any other battle of the war, and the cost reflected that. Slaughtered in the fields, utterly defeated in achieving its mission, the dispirited Union army withdrew from the field as darkness fell mercifully. They had suffered 12,700 casualties that day, compared to the rebels’ 5,300.

Still Burnside was not done. During a long war council with his commanders the next day he proposed sending fifteen thousand soldiers into the cauldron, believing that this large number of men would overwhelm rebel defenses. His staff argued against the plan. He then suggested occupying the town while withdrawing most of his army across the river. His officers had no confidence in him, and Burnside finally accepted his defeat. In the middle of the dark night the entire army marched silently away. “The history of wars does not record an instance of a retreat on so large a scale,” wrote Abbott, “under the very eyes of the foe, successfully accomplished without the loss of a man, a gun, or a caisson.”

Burnside’s effort to give Lincoln the victory he so desperately craved had been a disaster. As journalist Murat Halstead of the Cincinnati Commercial reported, “It can hardly be in human nature for men to show more valor, or Generals to manifest less judgment, than were perceptible on our side that day.… The occupation of Fredericksburg was a blunder.” The New York Herald wrote bluntly of Burnside that the enemy “had out-Generaled us.”

Lincoln did his utmost to find something positive in the events, telling his army, “The courage with which you, in an open field maintained the contest against an entrenched foe … show[s] that you possess all the qualities of a great army, which will yet give victory to the cause of the country.” But he confided to his aides, “If there is a worse place than hell, I am in it.”

As Lee and Jackson became legends, Lincoln searched desperately for a man capable of leading his army to victory. “They say at Washington that we have some thirty-eight to forty major-generals,” reported Harper’s Weekly, “and nearly three hundred brigadiers; and now the question is, have we one man who can fairly be called a first-class general?” At the end of January, Lincoln removed Burnside, replacing him with General “Fighting Joe” Hooker.

By that time, emancipation had been proclaimed, freeing all the slaves in rebel-held territory. While Robert E. Lee was furious about this, Jackson viewed it as more of a military problem, knowing that it would add tens of thousands of men to the Union ranks. In fact, he was quite ambivalent about slavery. While clearly he recognized the immorality of a system that subjugated some of God’s children, he also accepted its existence as the Lord’s will. It was not for him to question God. But as a good Christian he treated slaves fairly and with as much respect as was possible at that time. It was his task, he believed, to save their souls. As a child, he broke Virginia laws against educating slaves by teaching his cousin’s slave to read—and that slave then boarded the Underground Railway and escaped to Canada.

General Robert E. Lee’s almost mythical reputation grew even greater after he defeated the much larger force commanded by General Joe Hooker (above) at Chancellorsville. Suf fering a concussion from a cannonball’s near miss, the usually aggressive Hooker hesitated to counterattack—and as a result almost lost the Army of the Potomac.

According to some reports, Jackson’s family owned six slaves in the late 1850s. Two of them had asked Jackson to buy them after their owner had died and allow them to work off their debt, a not uncommon practice. When he married for a second time, in 1853, his wife already owned several slaves. In 1855, he ignored the loosely enforced educational laws and began a “colored” Sunday school class in Lexington and taught reading and the Gospel to black children. There were people who tried to stop him. As one of his former instructors in that school remembered, “Some of the Bourbon aristocracy criticized his action, and even went so far as to threaten prosecution. But a healthy Christian segment in the community sustained him, and he went forward in the path of duty.” He initially held the classes in his home, but when they grew to more than one hundred children, he had to move them to his church, and he awarded books and Bibles to the better students. Jackson actually seemed to be far more respected by the slaves than by the white population of Lexington.

He went to war with a slave named Jim Lewis, about whom little is known other than his complete devotion to Jackson. Jim Lewis was his “body man,” meaning he stayed close by him, doing everything necessary to allow Jackson to focus on the war. One widely repeated story described Lewis packing all of Jackson’s gear before being told to do so; when asked how he knew when it was time, he replied, “When I see the General get down on his knees and praying three, four times during a night I pack the baggage, for I know he going on an expedition.”

Even while commanding a great army, Jackson’s black Sunday school class remained vitally important to him. Only days after First Bull Run, his pastor, Rev. Dr. William S. White, received a letter from him. Presuming it included details of the Confederate victory, many people rushed to the church to hear it read. Reverend White mounted a box and opened the letter. “My Dear Pastor,” it read. “In my tent last night, after a fatiguing day’s service, I remembered that I had failed to send you my contribution for our colored Sunday school. Enclosed you will find my check for that object.” Inside the envelope was a $50 donation. The school became so popular and successful that years later Robert E. Lee praised it, admitting, “The negro Sunday school, which he taught with such devotion, exerted an influence on the negroes of Lexington which is felt to this day among the negroes of that whole region.”

By the spring of 1863, Stonewall Jackson had been at war for more than a year. It was time to meet his infant daughter, who had been born days before the Battle of Fredericksburg. Stonewall Jackson was married twice. His first wife, Elinor Junkin, whose father was the president of Washington College—later Washington and Lee University—had died after giving birth to a stillborn child. He married Mary Anna Morrison three years later—her father was the president of Davidson College—and their infant died less than a month after birth. Jackson stoically accepted these losses as God’s will, and so was overjoyed when his first surviving child, a daughter named Julia Laura, was born in November 1862. But as he warned his wife shortly after Julia’s birth, “Do not set your affections upon her, except as a gift from God. If she absorbs too much of our hearts, God may remove her from us.”

The price of victory proved impossibly high for the rebels. As Stonewall Jackson scouted the battlefield in the darkness, his own troops mistakenly shot him. His wife, Mary Anna Morrison Jackson (above), rushed to Chancellorsville with their child to minister to him, and he died with her nearby several days later.

In April, Jackson finally held his daughter. “During the whole of this short visit,” wrote Mary Anna Jackson, “he rarely had her out of his arms, walking her, and amusing her in any way he could think of.… When she slept in the day, he would often kneel over her cradle, and gaze upon her little face with the most rapt admiration.” But while Jackson was resting with his family, Hooker’s army was attempting a daring maneuver. This would be the last rest Jackson would have. When he was informed that Hooker was marching, he rushed back to join his men.

General Joe Hooker was the opposite of McClellan; he sometimes moved too rashly and too often expressed undue confidence. In fact, rather than pushing him to fight, Lincoln had to restrain him. Oddly, though, the nickname “Fighting Joe” had been given to him by an overzealous copy editor at the Associated Press, who inadvertently left the punctuation mark out of a headline that was supposed to read, “Still Fighting—Joe Hooker.” Personally, he despised it, explaining, “Don’t call me Fighting Joe, for that name has done and is doing me incalculable injury. It makes a portion of the public think that I am a hot-headed, furious young fellow, accustomed to making furious and needless dashes at the enemy.” That did not prevent Lee from mockingly referring to him as “F. J. Hooker.”

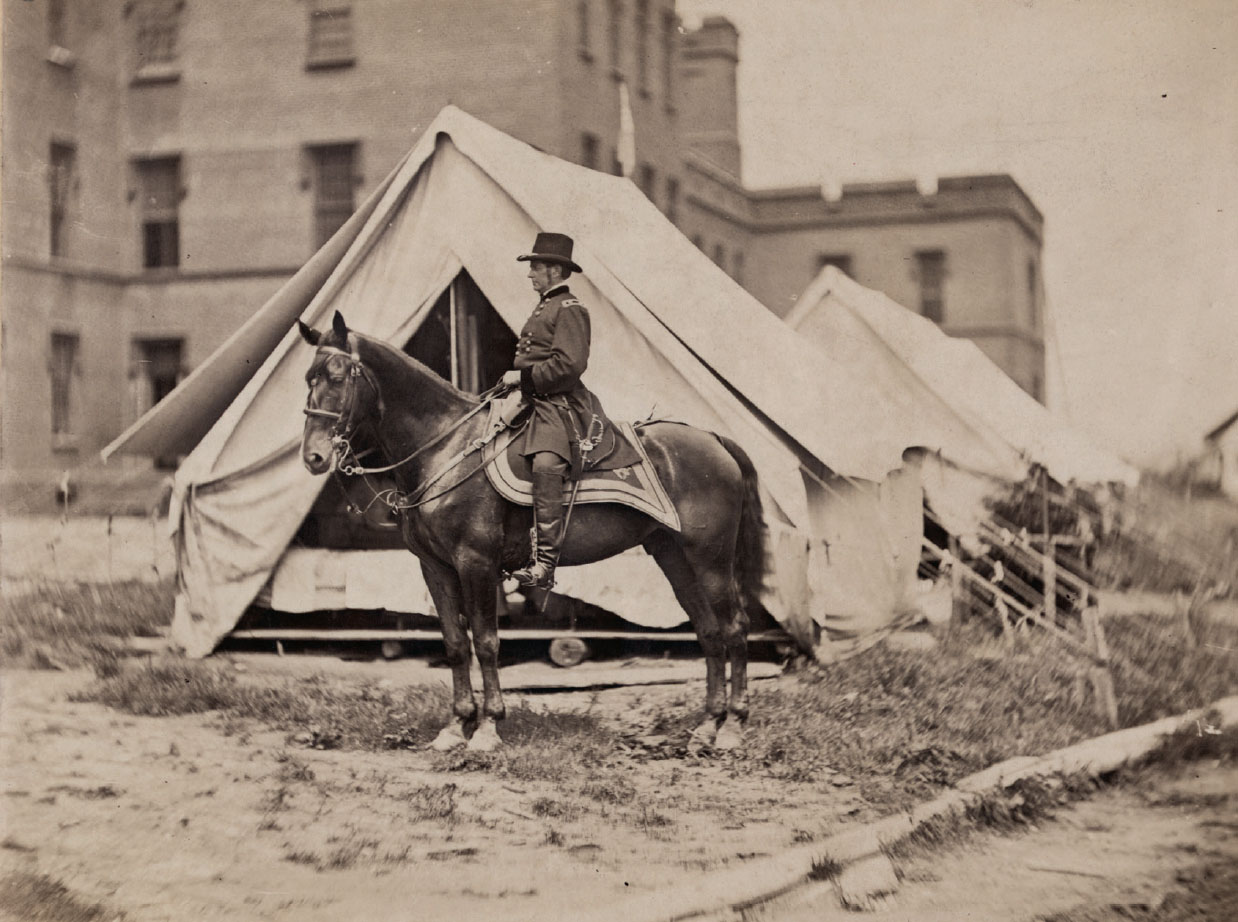

When Lincoln gave Joe Hooker command of the Army of the Potomac in the winter of 1863 (about the time Mathew Brady took this photograph), the confident general boasted, “May God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none.”

Also inaccurate is the belief that the slang term for a prostitute, “hooker,” was first applied to the working ladies who trailed his army. In reality, the derivation goes back much further in history and there are several possible explanations—none of them having to do with the general.

Joseph Hooker was another West Point graduate who had served nobly in the Mexican-American War. He “attracted attention,” according to newspapers, “by his gallant and meritorious conduct” at Chapultepec. Early in the Civil War his aggressive tactics had proved successful, although he was loudly critical of Union commanders. He had been especially infuriated at the waste of his men at Fredericksburg; his division had suffered massive losses when ordered to make several frontal assaults directly into Confederate lines.

When given command of the Army of the Potomac he raised morale by improving living conditions; he cleaned up camps and hospitals, substituted fresh food and bread for hardtack, increased security, granted longer leaves, and tried to ensure that his men had serviceable uniforms and equipment. Recognizing that the army too often moved blindly, he established a functioning intelligence service and even authorized a separate cavalry corps to mirror Confederate Jeb Stuart’s mounted force. And after doing all of that, he devised a strategy that might have won the war.

Rather than repeating Burnside’s fatal mistakes, he planned to circle Lee’s flank, forcing him to abandon his secure position around Fredericksburg and retreat or fight in the open field. In early May, it was reported, “the whole region was alive with movement,” as about one hundred thousand Yankees soldiers, each man carrying about sixty pounds of equipment, “concealing themselves in the dense growth of woods which lined the stream, and behind the curtain of hills,” crossed the upper waters of the Rappahannock and the Rapidan ten miles above the city, successfully flanking Lee’s army. Many of them crossed the rivers naked, their clothes bundled up and kept dry on the tips of their bayonets. They made camp near the tiny village of Chancellorsville, which consisted primarily of the Chancellor tavern. To create a diversion, an additional twenty thousand troops staged a clever ruse two miles below Fredericksburg. Under the watchful eyes of rebel spotters, two divisions marched over a hill and down a long bank, then crossed the river. Four more divisions with their artillery and baggage trains followed them—but instead of crossing the river they circled around through a ravine, completely hidden from the spotters, then marched over the hill again and again, creating the impression of a far larger force.

“It is with heartfelt satisfaction,” the confident Hooker reported, “that the commanding general announces to the army that the operations of the last three days have determined that our enemy must either ingloriously fly or come out from behind his defenses and give us battle on our own ground, where certain destruction awaits him.” But to Hooker’s discomfort, rather than the hard ground and open plain he had expected, the land surrounding Chancellorsville was a thick swampy marsh, covered by dense underbrush. The Wilderness, as it was known, “an impenetrable thicket,” made maneuvering difficult while providing cover for enemy troops.

Prior to the war Virginian Jubal Early had been passionately opposed to secession, but, like Lee, his loyalty to his state prevailed. Serving under Jackson at Chancellorsville, he fought in many of the major battles of the war, coming within sight of Washington, DC—but he hesitated and lost whatever opportunity he may have enjoyed.

General Lee made a fateful decision. Deciding that the attack below the town was a diversion, he once again split his army, sending Jackson with the bulk of his men to meet Hooker’s threat while leaving General Jubal Early to answer the Union attack on Fredericksburg. Dividing an already smaller force was questionable military strategy, but Lee had a not-so-secret weapon: the genius of Stonewall Jackson. Union observers in balloons reported that great numbers of rebel troops were abandoning their positions on the heights and racing toward Chancellorsville. In response, on Friday, May 1, Union general John Sedgwick launched an assault on the rebel fortifications at Fredericksburg, his men racing across the recently blood-soaked field, and this time overwhelming the greatly reduced force there. “The enemy,” reported the New York Times, “… fled in wild confusion, secreting themselves in the houses, woods, and wherever a place of concealment was afforded.” But most important, they continued to engage the Yankees in battle, holding them in place.

That same morning, Jackson ordered an attack on Hooker’s troops in the Wilderness, knowing the terrain would make it impossible for Union forces to organize a coordinated attack. As a Union soldier explained, “The passage through the tangled thickets broke up companies and regiments into crowds. Men were separated from their commands and absolutely lost in the woods.” By early afternoon the rebels had gained a small advantage, then began withdrawing under heavy fire. General Hooker’s officers pleaded with him to mount a massive counterattack that might overwhelm Lee’s exposed army, but the suddenly reticent general refused, instead withdrawing his bluecoats into a defensive position.

That night Jackson was told by his topographer that by following back roads his troops could swing around Hooker’s right flank and launch a surprise attack from the west. He and Lee sat alone by a fire as Jackson outlined his bold plan. The strategy meant splitting the Confederate army into two smaller forces, leaving the main body completely vulnerable if Hooker attacked. But Lee was willing to take that risk, confident that Hooker, assuming his army remained safe in its camps, would not take the initiative.

On May 2, Jackson led twenty-eight thousand men on the daring raid—among them twenty officers who had studied at VMI—believing the next few hours might well determine the outcome of the war. He rode up and down the columns, urging his men with “Press on! Press on!” Speed and surprise were everything. By late afternoon his troops had completed the maneuver. Jackson stood atop a ridge in the woods, looking down on the unsuspecting Union front lines. “His eyes burned with a brilliant glow, lighting up a sad face,” recalled General Fitzhugh Lee. “His expression was one of intense interest, his face was colored slightly with the paint of approaching battle, and radiant at the success of his flank movement … he did not reply once during the five minutes he was on the hill, and yet his lips were moving.… I know what he was doing then. Oh! Beware of rashness, General Hooker. Stonewall Jackson is praying in full view and in rear of your right flank!”

Shortly after five p.m. deer and rabbits came rushing out of the woods toward Hooker’s 11th Corps—followed instantly by the chilling rebel yell as almost thirty thousand men came pouring out of the woods. “The bolt had descended like lightning from the sky,” Abbott wrote. “The destruction of the whole army was menaced.… It was like a whirlwind’s rush and roar, as it sweeps the desert.… In one half hour the whole aspect of the campaign was changed.”

The Yankees fought back desperately. Union artillery opened up on the attackers, temporarily halting the advancing rebels. But Hooker’s flank had collapsed and the rout began. His men abandoned their weapons and raced for their lives, many of them swimming across the river to relative safety. The rebels pursued them until the sun set.

No one settled comfortably; the armies continued to move in the moonlight. Once Jackson held the strategic ground between the Yankees and the river, Lee would attack to finish the destruction of Hooker’s army. In the darkness Stonewall Jackson and several officers mounted their horses and began riding along the front lines, between the two armies, laying out their plans for the fight.

It was a very dangerous place to be, but Jackson paid little heed, knowing he was protected by the Lord’s grace. He certainly had substantial evidence of that. A cannonball had shot between his legs, causing no damage in the Mexican campaign! At Sharpsburg he had been riding with General Lafayette McLaws when an artillery shell passed right between them, striking a courier, but it did not explode. Jackson had said to McLaws, “The enemy, it seems, is getting our range,” then rode away quickly. “Much to my gratification,” McLaws admitted, then added that several times during the day Jackson had reminded him that “God has been very kind to us today.”

God was less kind on the night of May 2, 1863. As Jackson reconnoitered the battlefield he heard gunshots and artillery firing. Bullets struck nearby. Union troops were testing rebel lines.

Jackson rode easily. An aide grabbed his reins and said anxiously, “General, don’t you think this is the wrong place for you?”

“The danger is all over,” Jackson replied. “The enemy is routed. Go back and tell A. P. Hill to press forward.” But this time Jackson was wrong. Hooker had launched a night movement, desperate to recover some of the ground he had lost. As Union troops rode out of the Wilderness, Jackson and his men turned their horses and galloped back toward their own lines. Before departing on this dangerous tour, Jackson had given orders that his troops were to fire on any soldiers coming up the road.

In the darkness Jackson’s small party was indistinguishable from Union soldiers. Men of the 18th North Carolina, on edge waiting for the Union attack, saw several men racing toward them—and opened fire. Several of the men riding with Jackson were killed instantly. Jackson was hit three times, twice in his left arm and once in his right hand. He slipped from his saddle onto the ground as the firing finally stopped. A. P. Hill, informed that Jackson had been wounded, ran to assist him. “General, are you very much hurt?” he asked.

Jackson was alert and replied, “Yes, General, I think I am; and all of my wounds were from my own men.” He then asked Hill to fetch a skillful surgeon. As Union skirmishers fought closer to rebel lines he had to be moved. In fact, two Union soldiers actually wandered past only a few feet away and were taken prisoner, without ever learning how close they had been to the Confederate hero. Litter bearers carried him for several hundred yards before one of them was struck in the arm by shrapnel from a Union shell and fell, dropping Jackson hard onto the ground. He suffered an additional painful shoulder injury and started bleeding again. His wound again was tied off and, with the assistance of several men, he stumbled toward safety. The general commanding the North Carolina brigade, William Dorsey Pender, recognized him, although he did not appreciate the severity of his wounds. His men were being decimated by the shelling, Pender said, and he feared they could not hold the position. Witnesses reported that Jackson’s eyes flashed with fire as he ordered, “You must hold your ground, General Pender. You must hold your ground, sir.” That was the last battle order he ever gave.

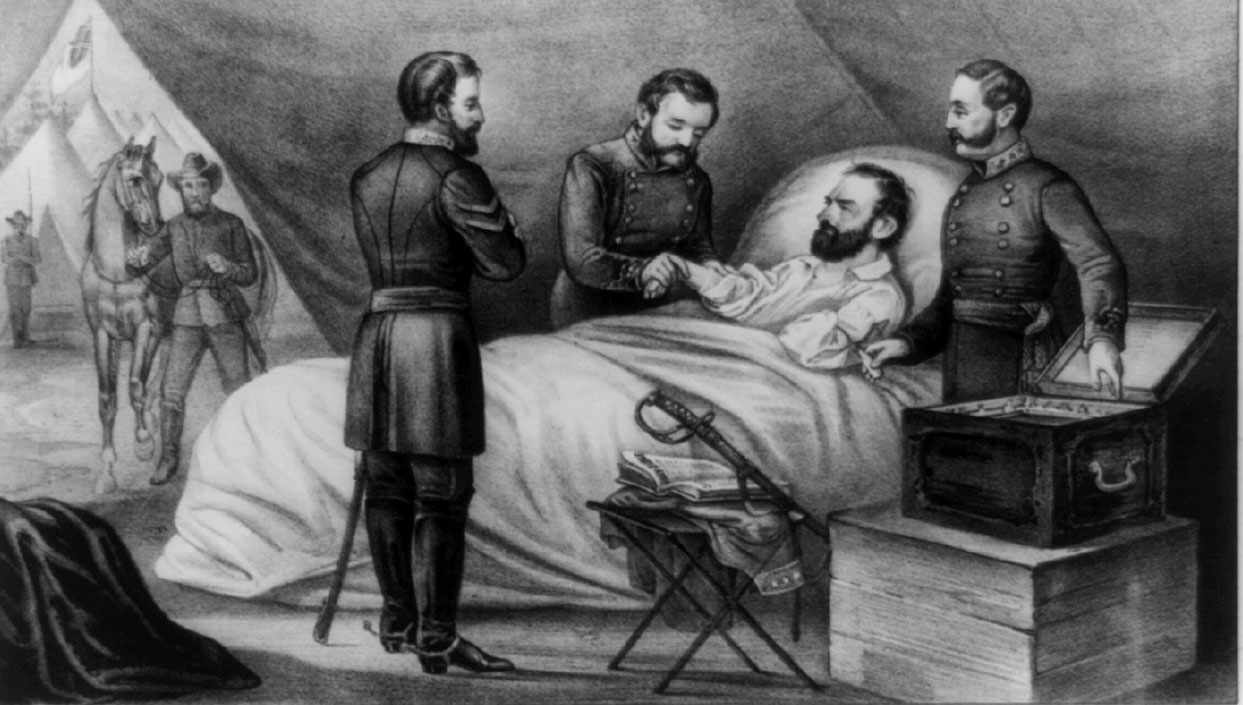

This 1888 chromolithograph portrays the shooting of Stonewall Jackson. Jackson’s death not only deprived Lee of his most able and daring officer but plunged the entire South into mourning. Jackson simply was irreplaceable.

Dr. Hunter McGuire gave him whisky and morphine and rode with him the four miles to the hospital at Wilderness Run. He nearly had died from blood loss, but surgeons were able to stanch the bleeding and save his life. His left arm was shattered, though, and Jackson concurred with the decision to amputate it. He recovered well and within a day, according to witnesses, was cheerful and talking about the battle.

It had been another great Confederate victory. The news that Stonewall Jackson had been gravely wounded enraged the rebels, who attacked again early the next morning, screaming, “Remember Jackson.” As a Northern newspaper reported, “Never on battle-field did men face death with more recklessness than did the troops of Jackson, inspired by their fanatic, unflinching leader.” General Hooker seemingly had lost his will to fight, failing to send as many as thirty-five thousand waiting troops into action. No one has ever been able to explain his decision. At about nine that morning, as he stood on the veranda of his headquarters, a Confederate cannonball shattered a pillar and knocked him unconscious. By the end of the day Lee was occupying Union headquarters and Hooker and his army were executing another “strategic withdrawal.”

Hooker’s generals wanted to launch another assault, confident that their superior numbers eventually would wear down the Southern army. They still had more soldiers ready to fight and continued to occupy several of the strategically most important positions on the battlefield. On the eve of the battle, an anxious Lee had admitted in a letter to President Davis, “As far as I can judge, the advantage of numbers and position is greatly in favor of the enemy,” and even after days of fighting the balance of power had not changed significantly. But Hooker was disoriented and confused, and instead of fighting, ordered a withdrawal.

One threat remained: at Fredericksburg General Sedgwick had finally successfully crossed the river and driven the rebels from the infamous stone wall. But Lee, having defeated Hooker, raced reinforcements six miles to the city to drive back Sedgwick’s attack. The brilliant strategy devised by Lee and Jackson had enabled the smaller rebel force to destroy Hooker’s larger army. More troops had been in the fight than in any battle of the entire war and the casualties were enormous: Hooker’s Army of the Potomac suffered 1,694 men killed, 9,672 wounded, and 5,938 missing, while Lee lost 1,724 killed, 9,233 wounded, and 2,503 unaccounted for.

As a student in Thomas Jackson’s class at the Virginia Military Institute, James Walker was dismissed only weeks before his graduation for challenging Jackson to a duel. The men reconciled and became so close that on his deathbed Jackson requested that Walker take command of his brigade. Walker’s gallantry at Gettysburg caused his men to pay him the greatest honor, nicknaming him “Stonewall Jim.”

But the greatest cost was the loss of Stonewall Jackson. Upon being informed that Jackson had been wounded, Lee said, “Jackson has lost his left arm … and now I have lost my right.” For a few days, though, it appeared that Jackson might survive. He was awake and alert, jubilant over the great victory. With great satisfaction he handed over control of the Stonewall Brigade to Colonel James Walker, who had been his student at VMI and had served bravely with him for much of the fighting. The healing process had begun. His amputated left arm was given a proper Christian funeral and buried not far from the hospital. When people visited him to commiserate about his wounds, he dismissed them, explaining, “I consider these wounds a blessing; they were given me for some good and wise purpose, and I would not part with them if I could.” As the battle raged around him, Lee feared Union troops would reach the hospital; he ordered Jackson moved twenty-seven miles farther to the rear.

But three days after being wounded, Jackson’s condition suddenly worsened. In the middle of the night he became nauseous and complained of terrible pain on his right side. Doctors examined him and found no wound, so they attributed it to his fall from the litter. Jackson asked Jim Lewis to lay a wet towel on his side. Although doctors were not yet aware of it, pneumonia, then a fatal condition, had set in, possibly caused by the fall.

A day later his wife arrived with his child. “I know you would gladly give your life for me, but I am perfectly resigned,” he told her. “Do not be sad. I hope I shall recover. Pray for me, but always remember in your prayers to use the petition, Thy will be done.” She took charge as his nurse and within a day his pain had disappeared; his surgeons tried to fight the disease but there was no effective treatment. They prayed and sang hymns. He was able to play with his daughter, whom he called his “Little Comforter.” A day later Mary Anna Jackson was honest with her husband, telling him he was dying. Jackson replied, “It will be infinite gain, to be translated to heaven and be with Jesus.”

Lee issued General Orders No. 61, announcing Jackson’s death and proclaiming, “We feel that his spirit still lives, and will inspire the whole army with his indomitable courage and unshaken confidence in God as our hope and our strength.” This Currier and Ives print depicting his deathbed was published after the war.

For a time on his last day he became deluded, giving nonsensical military orders, but he suddenly had a last rational moment, when he said quietly, “Let us cross over the river, and rest under the shade of the trees.” On the afternoon of May 10, Stonewall Jackson died. He was glad of the day, having reminded his caretakers only hours earlier, “It is the Lord’s Day.… I have always desired to die on Sunday.”

As Lincoln was learning, to his great distress, and as Lee knew, there are few great generals and only a handful of them might be considered military geniuses. Whatever combination of talent, skill, luck, and fortitude it requires to become that type of historic leader, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson possessed it. The day he died the Confederacy was holding its own in the war; Northern morale was at a low point and many people were questioning the continuation of the war. A Union soldier wrote to his father weeks after Jackson’s death, “I should be exceedingly sorry to see our country divided and I do not think there is many more willing to do more for their country than I am, but I am almost inclined to think that we shall have to acknowledge their independence.”

The Confederacy was stunned by Stonewall Jackson’s death. That he had been killed by his own guns made accepting it even more difficult. The city of Richmond turned out for his funeral. It was reported that as the long line of mourners walked slowly past his coffin to pay their respects, one elderly gentleman reminded them, “Weep not; all is for the best. Though Jackson has been taken from the head of his corps, his spirit is now pleading our cause at the bar of God.”

“You will have heard of the death of General Jackson,” Robert E. Lee lamented. “It is a terrible loss. I do not know how to replace him.” The answer, he was to find, was that replacing Jackson was impossible. And on that fact the war turned.

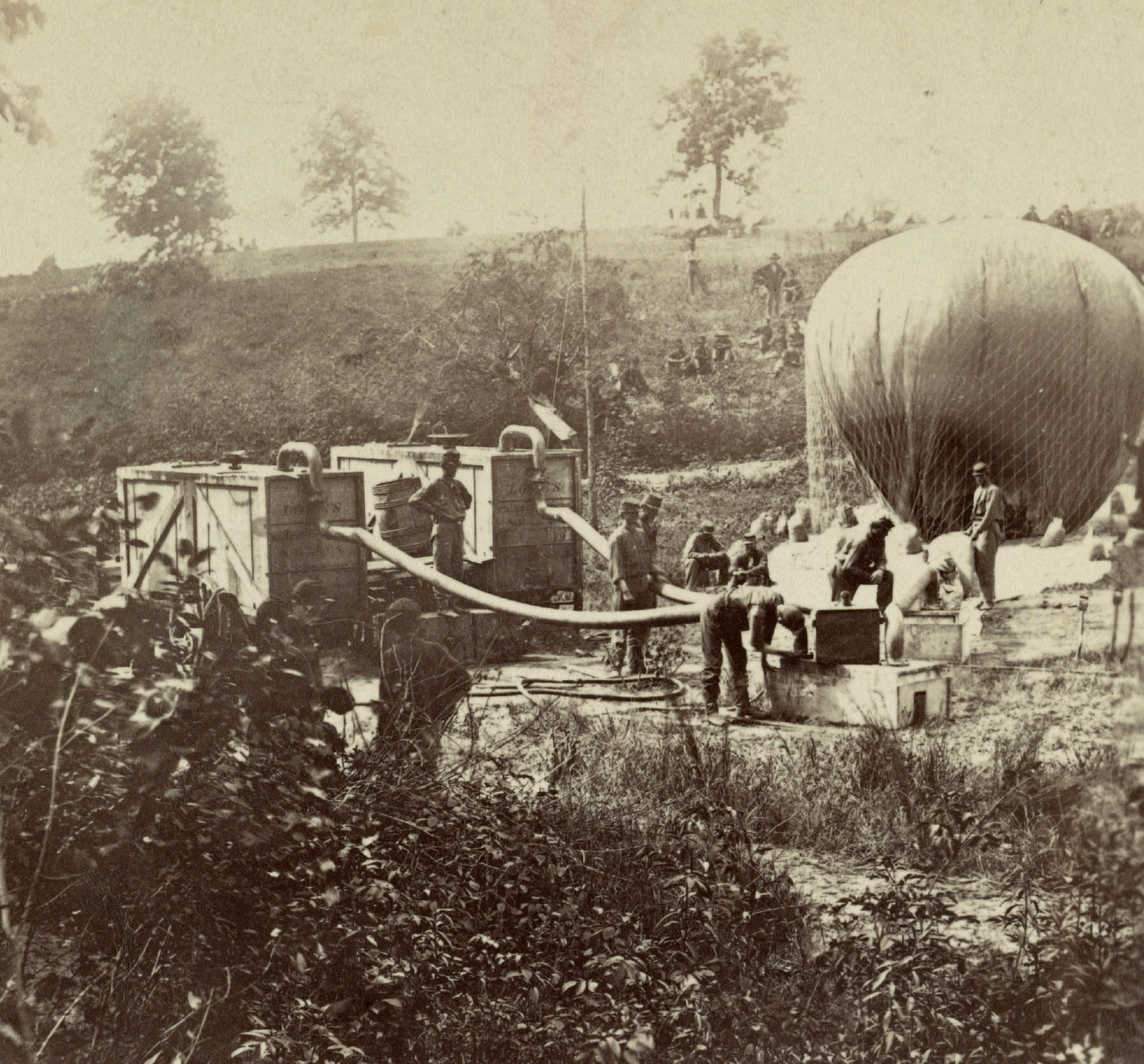

In the early years of the war, both sides used observation balloons to conduct aerial surveillance. Although the Union had a far more extensive program, and Lincoln was a supporter of these tethered balloons, which reached heights of one thousand feet or more, the program essentially was abandoned after 1863. But in that time it had proven its value.

The first observation balloons had been flown in wartime by the French more than half a century earlier. During the Civil War, Professor Thaddeus Lowe was selected to be the chief aeronaut for the Union army, building seven gas-filled balloons of different sizes. These balloons carried between one and five men and communicated with the ground by semaphore flags or, in the case of the larger balloons, by telegraph. The balloons were colorfully decorated; the side of the Intrepid bore a likeness of General McClellan being carried by an eagle.

Confederate attempts to create their own balloon corps were hampered by a lack of material, so they requested that women hand over their silk dresses, which were woven into a balloon and covered by varnish. Unfortunately, the ship carrying this first attempt went aground and was captured by Federal troops. But rebel balloons were employed near Richmond during the Seven Days’ Battle.

Balloons were used successfully in several engagements, including the Peninsula Campaign, at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, in the attack on Island No. 10, and, seen here, the 1862 Battle of Seven Pines. In the Brady photograph the Intrepid is being filled and the illustration shows how balloons were used to report troop movements and direct artillery fire.

Because of their position well behind the line, as well as the heights they reached, no balloon was struck by fire or shell. The most dangerous episode took place in April 1862, when a balloon carrying General Fitz John Porter broke loose from its moorings and floated over enemy lines at Yorktown. Fortunately the winds carried the general back behind his own lines, where he landed safely. “The General was master of his position in the air,” the New York Times reported, “as he generally is of that on land.”