Shoes.

According to legend, the Battle of Gettysburg began because Confederate soldiers had worn out their shoes and had been reduced to fighting barefoot. When, in the summer of 1863, General A. P. Hill was informed that shoes were available for his men in the nearby Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg, he permitted General Henry Heth to send in a party “and get those shoes.” A rebel patrol walked casually toward the quiet town, but as they mounted a rise in the road, they spotted several Union soldiers walking slowly toward them. Both sides were stunned. They raced back to their lines and spread the word that the enemy was at Gettysburg. Within hours commanders on both sides had called for reinforcements and tens of thousands of troops marched to the battlefield. The bloodiest battle of the Civil War was about to begin.

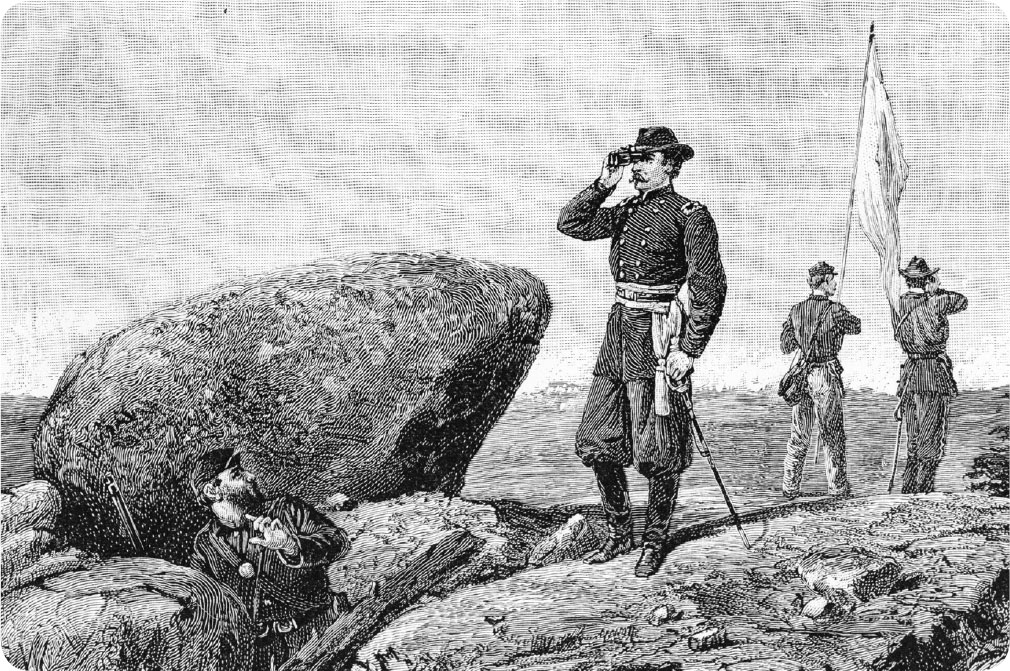

The printmaking firm Currier and Ives referred to itself as the “Grand Central Depot for Cheap and Popular Prints” that produced “colored engravings for the people.” Historical accuracy was less important than marketing. This detail from the Battle of Gettysburg was produced within weeks of the fighting.

General Ambrose Powell Hill led rebel troops throughout most of the major battles of the war. At Chancellorsville he replaced the wounded Jackson. He was criticized after Gettysburg for moving before Lee’s army was in place, but Lee greatly respected Hill’s abilities.

It is an often-told tale, but it isn’t quite true. While the Battle of Gettysburg did begin unexpectedly when the Yanks and the Rebs stumbled into each other, shoes had nothing to do with it. This was a battle for which each side had been preparing for weeks.

Lee’s great victory at Chancellorsville had emboldened the Confederacy. Now he was under pressure to march his undersupplied army into the fertile farmlands of Pennsylvania for replenishment, then continue to Washington or even Philadelphia. Southern newspapers, glowing with optimism, practically demanded that he bring the war into the North, to inflict on the Yankees some of the pain the Confederacy had suffered. Robert E. Lee allowed himself to be swayed; looking north he saw a weakened Army of the Potomac commanded by an indecisive general he had already humiliated. He was well aware that the antiwar Copperheads had gained strength in the last election and more and more Northerners were wondering if continuing the war was worth it. One more victory could turn them and force Lincoln to find a compromise. As he wrote to Jeff Davis, his army would “give all the encouragement we can, consistently with the truth, to the rising peace party of the North.”

Lee’s optimism gradually grew into overconfidence, which then moved toward arrogance. “There never were such men in an army before,” he told his generals. “They will go anywhere and do anything if properly led.” Robert E. Lee was about to make his greatest mistake. He ignored several important facts: that his army was still outnumbered, that he lacked sufficient supplies, and that the war had created an economic boom in the industrial North rather than inflicting the hardships that had become part of daily life in the South. But most of all he overlooked completely the reality that Stonewall Jackson was no longer at his side.

Lee’s intention to drive north was not a secret. The only question was where and when he would strike. For several weeks the two armies had skirmished along the Rappahannock, neither side able to gain an advantage. At Brandy Station, the largest cavalry battle of the entire war, bluecoats obtained General Jeb Stuart’s private papers, among them Lee’s orders for a rapid advance into Pennsylvania. Hooker sent some troops to that state’s border, while leaving sufficient troops in place to protect Washington.

But once again Lee’s army seemed to have vanished. No one could figure out where he was going. “The week was one of terror, confusion and doubt,” Abbott wrote. “The vast army of Lee, like a giant monster preparing to spring … making deceptive dashes then retiring stealthily into concealment, was working its way … to what precise point no one could dare predict. Philadelphia and Washington were equally in panic.”

By 1863, antiwar and anti-Lincoln sentiment was growing as Northerners began wondering if the huge number of casualties was worth it. This cartoon, published in Boston, attacks Lincoln’s mismanagement of the war.

The reputations of both Confederate general Henry Heth (left) and Union general George Meade (right) were soiled at Gettysburg. Heth was blamed for sending troops into the town before the rebel army was prepared to fight, while Meade was criticized for not pursuing and destroying the retreating rebels.

But when Lee got to Pennsylvania, it would not be Hooker waiting for him. As the rebel army created havoc in Pennsylvania, ransacking towns and farms, sending any black man suspected of being a fugitive back south, Hooker bickered with the War Department. Lincoln had to replace him but had no obvious choice—one newspaper even suggested seriously that the president himself was best equipped to lead the army in the field. When Hooker finally resigned in June 1863, Lincoln offered command to the competent but generally undistinguished general George Meade. Meade apparently was stunned by the directive and initially believed the officer who arrived with Lincoln’s message had come to relieve or arrest him, not give him command of the army. It was not a promotion Meade had sought, and he accepted it reluctantly, admitting, “I’ve been tried and condemned without a hearing, and I suppose I shall have to go to execution.”

Meade was in no position to advocate clever plans or complex strategies. “I’m going straight at them,” he wrote his wife, “and will settle this thing one way or the other.” His strategy, he informed Lincoln, was “to find and fight the enemy.”

While Union commanders searched for Lee, the Confederates were equally blind. While history credits Jeb Stuart’s cavalry as being the eyes and ears of the Southern army, historians like Dr. Allen Guelzo, the Henry Luce Professor of the Civil War Era at Gettysburg College, describe that as one of the greatest myths of the war, pointing out that the cavalry rarely provided useful intelligence. Stuart set out on June 22 to circle behind the Yankees’ right flank in order to harass them, turn their attention from the main thrust, and meanwhile assess their true strength. But to his consternation, the Union army was spread out over a much greater landscape than he had assumed, forcing him to ride much farther east than intended, during which time he was completely out of touch with Lee, so Lee was forced to plan his strategy without any information.

By dividing his army into three corps, Lee had successfully created confusion, but as he became aware that the Union army was closer than he had believed, he moved rapidly to concentrate his forces, abandoning a planned attack on the capital of Harrisburg, and ordered his army to unite near the prosperous town of Gettysburg.

When Meade took command on June 28, it had already become apparent that Lee was massing his army nearby. On the night of June 29, Johnny Reb’s campfires were visible from the town. The new commanding general immediately ordered his army to meet the threat, and on the eve of battle, as many as 150,000 soldiers slept uneasily within a few miles of Gettysburg.

On June 30, as Confederate general Heth would write only eight weeks after the battle, “I ordered Brigadier General Pettigrew to take his brigade to Gettysburg, search the town for army supplies (shoes especially), and return the same day.” It was Pettigrew’s scouts who spotted bluecoats in the street, and the myth that the Battle of Gettysburg was fought over shoes was born.

Reinforcements for both sides continued to pour into the area. The Yankees would be bolstered by volunteers. Two days earlier Governor Curtin had issued an appeal for sixty thousand Pennsylvanians to take up arms “to defend their soil, their families, and their firesides.” Among the men who responded was sixty-nine-year-old John Burns of Bendersville, a hard-drinking veteran of the War of 1812 who made the dubious claim of being descended from Scottish poet Robert Burns. He had attempted on several occasions to volunteer but had been rejected because of his age. But now the call went out for any able-bodied man who could aim a rifle, and on the morning of July 1 he dressed in his fanciest clothes—a swallow-tailed blue coat with gilt buttons and a black silk hat—and fell into the ranks of the 150th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

Upon being informed that an unidentified number of Union soldiers were in the town, Hill decided to send a sizable contingent into Gettysburg to assess the situation. At seven thirty a.m., a Union soldier named Marcellus Jones fired the first shot. The battle began before either army was fully prepared. Lee would have much preferred to wait until Longstreet’s corps and Stuart’s cavalry had gotten there. Meade reported, “A battle at Gettysburg is now forced upon us,” and then added later, “We may fight it out here just as well as anywhere else.” The battle was much larger than either commander had anticipated, and when it became apparent to Meade that a decisive victory could bring an end to the war, he said, “Very well. I select this battlefield!”

“The old hero of Gettysburg,” crusty John L. Burns, was photographed by Mathew Brady with his rifle and his crutches outside his home as his fame grew throughout the nation in the weeks following the Battle of Gettysburg. Burns became the subject of poems and short stories in Northern periodicals.

The fighting intensified throughout the first day. Union general John Reynolds rushed his Iron Brigade into the fight—and was killed by a sharpshooter. As the rebels drove Reynolds’s troops back, the elderly civilian volunteer John Burns suffered several slight wounds. While painful, they were not life-threatening—but they prevented him from retreating with the brigade. That put him in a desperate position: the penalty for a civilian—a so-called bushwhacker—caught on a battlefield was summary execution. Burns discarded his weapon and ammunition and crawled onto a cellar door, where Confederate troops found him. As a rebel doctor treated his wounds, Burns claimed he was a noncombatant and had been out searching for his cow. He was allowed to return home, where his wife reportedly called him “an old fool … getting holes in his best clothes.” But in General Abner Doubleday’s post-battle report, he praised Burns, who became nationally known as “the Hero of Gettysburg.” And poet Francis Bret Harte immortalized his deed in “John Burns of Gettysburg,” writing:

While Burns, unmindful of jeer and scoff,

Stood there picking the rebels off,—

With his long brown rifle, and bell-crown hat,

And the swallow-tails they were laughing at.

This map of the three days’ fighting at Gettysburg illustrates the difficulty faced by the rebels (thick lines) in dislodging the Union troops from the hills outside the town.

But Burns was among the lucky ones, able to leave the battlefield with only minor wounds. During the fighting that day the Yankees were driven back through the town, Meade’s “troops running along every available road” in retreat; at one point a brigade was caught between two rebel brigades who ran alongside them, firing as they ran, wiping out half the Union troops. Thousands of bluecoats were captured. It was an inglorious retreat, and, for a time, it appeared that Gettysburg was to be another rebel victory. But during this scramble for safety, General Oliver Howard’s men were able to seize and hold the high ground atop Cemetery Hill, a vital strategic position just south of the town. For the next three days, dug-in Union troops fought off repeated rebel attacks on their positions.

This is a misleadingly tranquil view of Gettysburg taken from Evergreen Cemetery gatehouse on Cemetery Hill only days after the end of the battle.

Probably more than on any other single day for the rest of the war, this was the time and place where Jackson could have made a difference. Lee urged Jackson’s replacement, General Richard Ewell, to launch a frontal assault on Cemetery Hill, “if practical,” before Union troops could fortify their defensive positions. But Ewell lacked the fortitude, electing not to risk that attack. Historians believe that Jackson would not have hesitated to accept that challenge and might well have turned the battle that day.

After finally arriving in the afternoon of the first day of fighting, Longstreet suggested that Lee try to maneuver around the Union left flank, to get behind Cemetery Hill and force Meade to leave the high ground to pursue him. But without sufficient intelligence, Lee had no idea what might be waiting for him on the other side of the ridge. He also lacked respect for Meade, believing his own army and his officers to be far superior, and so he remained quietly confident of victory. “The enemy is there,” he told Longstreet, “and I am going to attack him.” So as the first night fell, Union troops in the hills could look down upon the rebels occupying the town.

Throughout that night, newly arrived Union troops continued to reinforce the hills surrounding the town. With their stone walls, abundant trees and rocks, and a clear view of the fields below, they were an ideal defensive position. General Winfield Hancock called Gettysburg “the strongest position by nature upon which to fight a battle that I ever saw.”

By noon on the second day, both armies were fully reinforced, each with about eighty thousand men in the field. Into the early afternoon Lee tried to dislodge the entrenched Union troops, pounding the hills with a massive artillery barrage. When Union soldiers tried to move to cover, sharpshooters hiding behind quickly constructed barricades in the town picked them off. The soldiers on the ridge dislodged tombstones and used them to provide protection. Finally, at four o’clock in the afternoon, Longstreet attacked the left flank with an estimated thirty thousand troops. As one Northern newspaper described the attack, “It was not an attack in line, it was not a charge, it was a melee, a carnival of death. Men hewed each other’s faces; they grappled in close embrace, murder to both; and all through it rained shot and shell from one hundred pieces of artillery along the ridge.” As rebel troops battled the Union defenders, several regiments successfully rounded the flank and got in position to roll up the Union lines. The next high ground—literally the last point of defense between the Confederates and the remainder of the Union army (now occupied with fending off a frontal assault)—was the 650-foot-high hill known as Little Round Top.

In the chaos, Little Round Top had been left unprotected for much of the day. Fortunately, Meade, perhaps sensing this weakness, had sent his chief of engineers, General Gouverneur Warren, to assess the situation. Warren was stunned to find this vital point undefended and moved rapidly to fortify it. Among several units moved into position in the woods on Little Round Top was the 328-man 20th Maine, under the command of Lt. Colonel Joshua L. Chamberlain. “This is the left of the Union line,” he was told. “You are to hold this ground at all costs.” They got there and dug in just in time to save the Army of the Potomac.

On the second day of the battle, Meade’s chief engineer, General Gouverneur K. Warren, discovered that a “rocky hill” south of the town (which would become known as Little Round Top after the battle) had been left undefended and would have given the Confederates a perfect position to shell entrenched Union troops on Cemetery Hill. Warren, seen here in an 1888 sketch, managed to get reinforcements in place as the rebels were climbing the hill and to defeat them.

The rebels began fighting their way up the hill. The outnumbered defenders raked them with fire but still the enemy kept coming and coming. The fighting continued throughout the afternoon until the enemy was less than thirty yards away—and those defenders who had not been killed or wounded were down to their last few bullets. Lieutenant Holman Melcher recalled, “The time had come when it must be decided whether we should fall back and give up this key to the whole field of Gettysburg, or charge and try to throw off the foe.”

If there truly was a moment on which the outcome of the war hinged, it occurred on July 2 on Little Round Top, when Maine professor Joshua Chamberlain organized a defense and defeated attacking Confederates in hand-to-hand fighting.

History has given credit for the heroics of the next few moments to Chamberlain, who indeed was in the thick of it, but there is ample evidence that what happened next was the result of confusion combined with the extraordinary bravery of the men of the 20th Maine. Some historians believe that Chamberlain and Melcher had agreed only to send several men into no-man’s-land to try to assist the wounded. When Melcher fixed his bayonet, the rest of the troops heard the telltale snap and did the same. Seconds later Chamberlain gave the one word order, “Bayonet!” and Lieutenant Melcher drew his sword and sprang forward. The rest of the 20th Maine quivered for an instant, then with a great cheer followed, charging directly into enemy lines.

It was never determined what Chamberlain actually meant by that one word, though many people believed it was the first word of a longer order. The intention made no difference. Melcher flashed his sword and led the charge down the slope, screaming, “Come on, come on boys!” with Chamberlain only a few paces behind him. The charge down the hill stunned the rebels. As Chamberlain wrote in his after-action report, “The two lines met and broke and mingled in the shock. The crush of musketry gave way to cuts and thrusts, grapplings and wrestlings.”

Although they could not have known it at the time, the extraordinary courage of Chamberlain’s 20th Maine Infantry may not have been necessary: Confederate colonel William C. Oates, whose troops had been decimated by the withering fire from the hilltop, had made a decision: “To save my regiment from capture or destruction, I ordered a retreat.”

When the fighting ended that day, the Union lines had staggered but held. Both armies had suffered tremendous casualties. “The dead literally covered the ground,” Colonel Oates wrote. “The blood stood in puddles on the rocks. The ground was soaked with the blood of as brave men as ever fell on the red field of battle.”

Later that night, New York Times correspondent Samuel Wilkeson made a dreadful discovery: he found the body of his son, nineteen-year-old Bayard Wilkeson. Wilkeson had been commanding an artillery battery on the first day of fighting. A Confederate shell had passed through his horse and shattered his own leg below the knee. Incredibly, he had cut off the remains of that leg, then was carried to a hospital where he lay bleeding to death for seven or more hours. Several days later his father’s account of this family tragedy was published on the front page of the Times and roused the nation, serving as a symbol for the suffering of both North and South—and perhaps also serving as the model for the legendary speech that Lincoln gave on this battlefield several months later. “Oh, you dead, who at Gettysburg have baptized with your blood the second birth of Freedom in America, how you are to be envied!” Wilkeson wrote. He added, “Who can write the history of a battle whose eyes are immovably fastened upon … the dead body of an oldest born.”

But even as he wrote those words, there remained one more day of fighting at Gettysburg. At the end of the second day of fighting, Meade gathered his commanders and discussed the possibility of withdrawing, but his officers insisted that they must hold their “immensely strong” position. At that meeting Meade warned General John Gibbon that Lee, having failed with attacks on both flanks, would likely come directly at him in the center of the line on the third day.

Lee believed that the Yankees were so demoralized that he could launch a frontal assault across almost a mile of broad and open field, directly into the heart of the Union guns. General Longstreet tried desperately to dissuade him, telling him that “no fifteen thousand men ever arrayed for battle can take that position.” But Lee insisted, believing the war could be won on that battlefield. “Never was I so depressed as upon that day,” Longstreet wrote. “I felt that my men were to be sacrificed, and that I should have to order them to make a hopeless charge.”

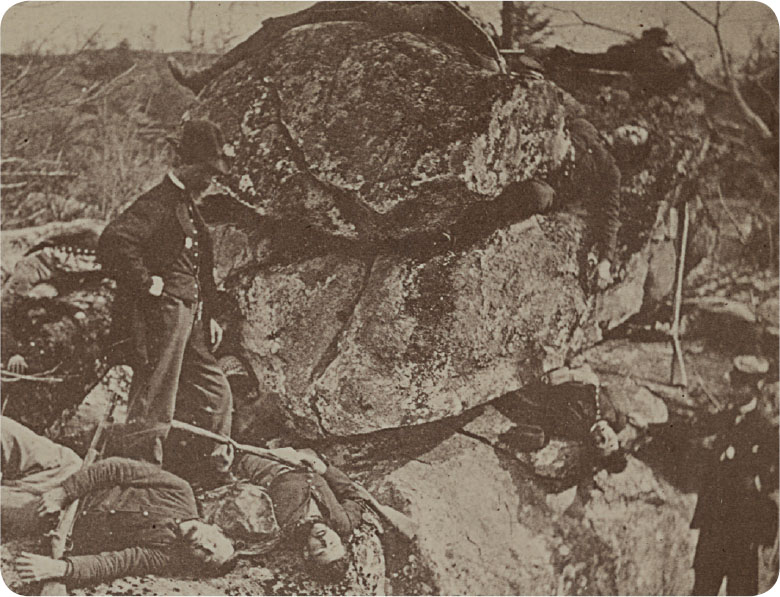

In the battle for Little Round Top, the Union suffered 565 casualties, including 134 killed, and the rebels lost 1,185 men, with 279 killed. Here two doctors examine fallen men only hours after the battle.

Lee tried one last gambit before ordering the charge. In an attempt to lure Meade into leaving his well-fortified position, he marched his troops out of the city, retreating to Seminary Ridge. “For some time the town had scarcely a soldier in it,” reported Harper’s Weekly. “Scores of dead and wounded men and horses, with broken wagons, bricks, stones, timber, torn clothing, and abandoned accoutrements, lay there. The frightened inhabitants peered out of their windows to see what the armies were doing to cause such a lull, and, almost afraid of their own shadows, they hastened away and crouched in corners and cellars at the sound of every shot or shell.”

Meade refused to take the bait. Through the morning of July third the battlefield remained eerily silent, the lull before the coming storm. At one thirty, Lee began a great artillery barrage, hoping to soften Union defenses. An estimated 160 big guns rained explosives and iron on Cemetery Hill. Most of the shells, however, overshot their targets, landing well behind Union lines and destroying supplies but causing few casualties. To preserve ammunition, Meade allowed only some of his cannons to respond, and eventually he ordered them to stop firing, “as if silenced by the fire of the enemy,” wrote Abbott, “while his gunners threw themselves flat upon the ground.” Then, certain an attack on his center was coming, he positioned all of his big guns on either side of the field. And waited.

The Confederate barrage continued relentlessly for two hours. By then the Union artillery had ceased firing and whatever damage had been done was obscured completely by clouds of gun smoke. When the firing ended, General George Pickett, whose division was to lead the attack, asked Longstreet, “General, shall I advance?”

Longstreet could barely respond. Pickett remembered, “Presently, clasping his other hand over mine without speaking he bowed his head upon his breast. I shall never forget the look in his face nor the clasp of his hand when I said, ‘Then, General, I shall lead my division on.’”

Three rebel divisions, comprised of almost fifteen thousand troops, came out of the woods on Seminary Ridge, assembling in plain view. It was time: They had been marching for days without sufficient rations and limited water. Three days of fighting had deprived them of sleep. And on this sweltering hot day, as temperatures approached 90 degrees, many of them were dressed in woolen uniforms. Whatever the result, this battle was going to end here.

Their line extended more than a mile across and a thousand yards deep. At two o’clock in the afternoon, with “a long, loud, unremitting, hideous screech, from thousands of voices,” they began what has become honored in history as Pickett’s Charge.

General George Pickett commanded the three Confederate brigades that led the doomed frontal assault into the heart of Union lines on the last day of the Battle of Gettysburg. Although several other Confederate brigades also joined the attack, it is Pickett’s name that lives in history. Pickett’s Charge has become a metaphor for hopeless gallantry and the waste of brave lives in a futile ef fort.

They ran with great daring and courage straight at Cemetery Hill, they ran as the men around them fell, they ran for their lives, but there was no outrunning the guns that opened fire on them. Federal artillery positioned on both sides began shelling the attackers, opening up with shot and shell, blowing great holes in the ranks. As the Southerners got within four hundred yards of the Union lines, the artillerymen began firing grapeshot and canister. Rebels fell by the hundreds, by the thousands, and yet they kept coming. When one flag bearer fell, another man picked up the colors and advanced them, and when he fell, still another replaced him. When Pickett’s men came out of the smoke at the base of the hill, the Yankees opened up with small arms. “Volley after volley he [General Gibbons] poured into the surging mass,” wrote Abbott, “and when the smoke cleared away, the brave charging lines were gone—not broken, not retreating, but gone—gone like leaves before the wind.”

Incredibly, a small number of men—about two hundred—under the command of Brigadier General Lewis Addison Armistead managed to reach the stone wall on the south portion of Cemetery Hill. Sticking his hat on his bayonet and raising it high as a beacon to guide his troops, he screamed, “Come on boys, we must give them the cold steel! Who will follow me?”

His men followed him over the wall. They pushed back the federal troops and turned two of their own cannons on them—only to discover there were no shells left. Within minutes Armistead was hit multiple times and fell, to die two days later. Many historians regard this brief success as the high point of the entire war for the Confederacy, the closest they came to an ultimate victory. But it lasted only minutes. When Meade learned of the only successful thrust into his lines he immediately dispatched reinforcements, who quickly and brutally repulsed the incursion.

The Civil War was often fought employing traditional military strategies against new and powerful weapons. The result was massive casualties. Nowhere was that more apparent than at Gettysburg, during which acts of extraordinary courage became commonplace. The chaos, the death and destruction, and the confusion are all on display in this artwork.

The tattered remains of the three Confederate divisions retreated under fire to Seminary Ridge. Miraculously the town of Gettysburg had suffered very little damage. Union troops moved cautiously through the town, killing or capturing any Confederate stragglers. They pursued the rebels all the way to Seminary Ridge but didn’t make much of a fight there. Pickett’s glorious charge was over. More than half of the men who charged into the Union guns that morning were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner.

General Pickett’s description of the aftermath is still haunting:

No words can picture the anguish of that roll-call—the breathless waits between the responses. The “Here” of those who, by God’s mercy, had miraculously escaped the awful rain of shot and shell was a sob—a gasp—a knell—for the unanswered name of his comrade.… Even now I can hear them cheering as I gave the order, “Forward!” I can feel the thrill of their joyous voices as they called out all along the line, “We’ll follow you, Marse George. We’ll follow you—we’ll follow you.” Oh, how faithfully they kept their word—following me on—on—to their death, and I, believing in the promised support, led them on—on—on—Oh, God!

The Army of the Potomac also had been mauled by three days of fighting. Meade, fearing that Lee would mount one more attack in desperation the following morning, collected his wounded from the battlefield but kept his defenses in position. But there was no fight left in the rebels. On the fourth, Lee sent a note to Meade requesting an exchange of prisoners. Meade refused, believing the four thousand Union prisoners held by the Confederates would be a heavy weight on Lee. As the exhausted Yankees held their positions, the rebels slipped away from the battlefield. They took their wounded with them, and their long line of retreat stretched for seventeen miles. As Alabama artilleryman Napier Bartlett recalled, during the forty-mile march “the whole of the army was dozing while marching and moved as if under enchantment or a spell—asleep and at the same time walking.” Fearing another Union attack, Confederate commanders prohibited any stopping or resting.

Gettysburg proved to be the bloodiest battle of the entire war. The whole town of Gettysburg was transformed into a vast hospital, with casualties being treated in homes, stores, even barns. Although precise numbers will never be known, officially in the three days of fighting Union forces suffered 23,049 casualties, which included 3,155 killed, 14,529 wounded (an unknown number of whom would eventually die), and 5,365 missing. Lee lost almost 40 percent of his army, reporting 28,063 casualties: 3,903 killed, 18,735 wounded, and 5,425 missing. Six Confederate generals died on the battlefield and five more suffered serious wounds. In Pickett’s command two generals were killed, as were seven colonels and three lieutenant colonels. “Only one field officer of my whole command … was unhurt, and the loss of my company officers was in proportion,” he reported. Five thousand horses and mules were killed. After the battle a small mountain of amputated arms and legs grew on the fields and were buried in huge pits. Incredibly, only one civilian was killed—a woman named Ginnie Wade died when a stray bullet ripped into the house on the south side of the town and struck her while she was tending a sick relative. Elderly volunteer John Burns survived his wounds. Weeks later, when President Lincoln came to the town to honor the men of this battle with a brief speech, he invited John Burns to sit with him.

For the first time in history, cameras were able to record the brutality of battle. In the aftermath of Gettysburg, one of the most difficult problems was how to bury all the dead, among them these men killed in a wheat field on the second day of fighting.

The dead by the hundreds were left bloating in the sun. The government hired Gettysburg residents to bury them, giving them hooks so they might grab the bodies by their belts and drag them into mass graves.

More than sixty Medals of Honor were awarded for gallantry on those three days, and among the recipients was Joshua Chamberlain.

Lee had suffered a devastating defeat. His aura of invincibility was gone forever. His officer corps was decimated. While the Union also suffered a great number of casualties, it had a much greater reservoir from which to eventually replenish its ranks. As one reporter noted, “Numbers might be restored, broken spirits never.” In the North, there finally was a taste of great victory, and the fervor of the Copperhead Democrats was quieted. There were many battles still to be fought, but the Confederacy would never recover from the miscalculations of Gettysburg.

The North celebrated the victory. Within weeks, books about the great battle were being published. Stories of heroism, of survival, of simple human decency in the midst of incomprehensible horror riveted readers. In What We Did at Gettysburg, a woman told the story of refusing to leave her kitchen when the battle started because “we was all a baking bread round here for the soldiers, and had our dough a rising. The neighbors they ran into their cellars, but I couldn’t leave my bread.… I stood working it till the third shell came through.” She had refused to leave, she explained. “If I had, the rebels would a come in and daubed the dough all over the place.”

Along with Mathew Brady and the other Civil War photographers, artists like Edwin Forbes were able to capture the life and hardships of the soldiers. This 1870 oil painting, Pursuit of Lee’s Army. Scene on the Road Near Emmitsburg—Marching Through the Rain, depicts Union troops on the march after the battle, but without any sense that a great victory has just been won.

The fallout from the battle shaped both armies for the remainder of the war. As the rebel army limped back toward the Potomac, Lincoln urged Meade to pursue Lee, attack him, and finish the war. Lee expected to make an orderly crossing of the Potomac, but heavy rains swelled the river and made it impossible for the Confederates to cross safely. As they paused on the northern bank, on the heights known as Marsh Run, Meade began planning an all-out attack. But his commanders were almost unanimous in their advice: The army was not ready to fight again. The attack should be delayed. Meade paused, giving Lee sufficient time to fashion a pontoon bridge of house and warehouse timbers, enabling his army to cross to the relative safety of Virginia. The crossing itself was perilous as many troops had to wade across an angry river with water to their armpits.

Meade continued his cautious pursuit, maintaining watch over all possible routes to Washington. But he failed to attack. In fact, many historians believe Meade had stumbled into the correct decision. Lee’s army had regained its composure and was packed into a strong defensive position—and many of them, having tasted defeat, were craving another opportunity to fight the Yankees. Meade might well have ended the war on the banks of the Potomac, but the price would have been extraordinarily high.

Lincoln was furious that Meade had failed to press his advantage. “We had them within our grasp,” he said later in despair. “We had only to stretch forth our hands and they were ours. And nothing I could say or do could make the army move.” He had tried to prod Meade into ending the war there and then. At the president’s behest, General Henry Halleck had telegraphed Meade, telling him, “The enemy should be pursued and cut up.… I need hardly say to you that the escape of Lee’s army without another battle has created great dissatisfaction in the mind of the President.”

Meade angrily offered to resign—but that offer was rejected. Lincoln instead wrote a long letter to him, explaining that it appeared to him that Meade was “not seeking a collision with the enemy, but were trying to get him across the river without another battle,” adding, “I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape—He was within your easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with our other late successes, have ended the war—As it is, the war will be prolonged indefinitely.… Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasurably because of it.”

Lincoln paused and considered the consequences of sending this letter, and never mailed it. Instead he wrote to General Howard several days later, after admitting that he had been “deeply mortified by the escape of Lee across the Potomac.” He tempered his criticism, concluding, “A few days having passed, I am now profoundly grateful for what was done, without criticism for what was not done. Gen. Meade has my confidence as a brave and skillful officer, and a true man.”

Lee also was in despair. He had been deeply shaken by the defeat. He took complete responsibility for the lives lost in Pickett’s Charge on the third day, telling the survivors, “You men have done all that men could do. The fault is entirely mine.” In his depression he offered his resignation to President Jefferson Davis. He wrote:

We must expect reverses, even defeats. They are sent to teach us wisdom and prudence, to call forth greater energies, and to prevent our falling into greater disasters.… The general remedy for the want of success in a military commander is his removal. This is natural, and in many instances proper; for no matter what may be the ability of the officer, if he loses the confidence of his troops disaster must sooner or later ensue.

I have been prompted by these reflections more than once since my return from Pennsylvania to propose to your Excellency the propriety of selecting another commander for this army.

Jefferson Davis rejected the offer, pointing out, “But suppose, my dear friend, that I were to admit, with all their implications, the points which you present, where am I to find that new commander who is to possess the greater ability which you believe to be required? … To ask me to substitute you by someone in my judgment more fit to command, or who would possess more of the confidence of the army, or of the reflecting men of the country, is to demand an impossibility.”

Gettysburg would later be remembered as the most hallowed ground of the Civil War. But in its more immediate aftermath, both the North and South were stunned by the brutality. Even with the advent of telegraphy, it took weeks before accurate reports spread throughout the country; and for some weeks Southerners believed that Lee had won a great victory—with some newspapers even reporting that Lee’s army was in Washington. It would be several more months before the entire story was known.

And then President Lincoln decided to go to Gettysburg to honor the men who had sacrificed there.