“War is hell,” Union general William Tecumseh Sherman supposedly said.

And to the Confederacy, Sherman was the Devil who brought with him the fires of damnation.

Although Sherman probably never said those precise words, there is no doubt that he believed them. When Grant moved on Richmond, he ordered Sherman to strike into the deep South, “to move against Johnston’s army, to break it up, and to go into the interior of the enemy’s country as far as he could, inflicting all the damage he could upon their war resources.”

Grant did not issue more specific written orders, he explained, because he and Sherman had spoken at length and both men knew the terrible things that had to be done. Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and the Confederate army had made clear there would be no negotiated settlement, no compromise, that they intended to fight to the end of their capabilities. Accomplishing that, both Grant and Sherman realized, required inflicting great pain upon the South, a strategy that began with ripping up the fragile railway systems that held the South together.

When ordering the residents of Atlanta to evacuate their city, Sherman wrote to Mayor James Calhoun and the city council, “War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out.… You might as well appeal against the thunder-storm as against these terrible hardships of war. They are inevitable.”

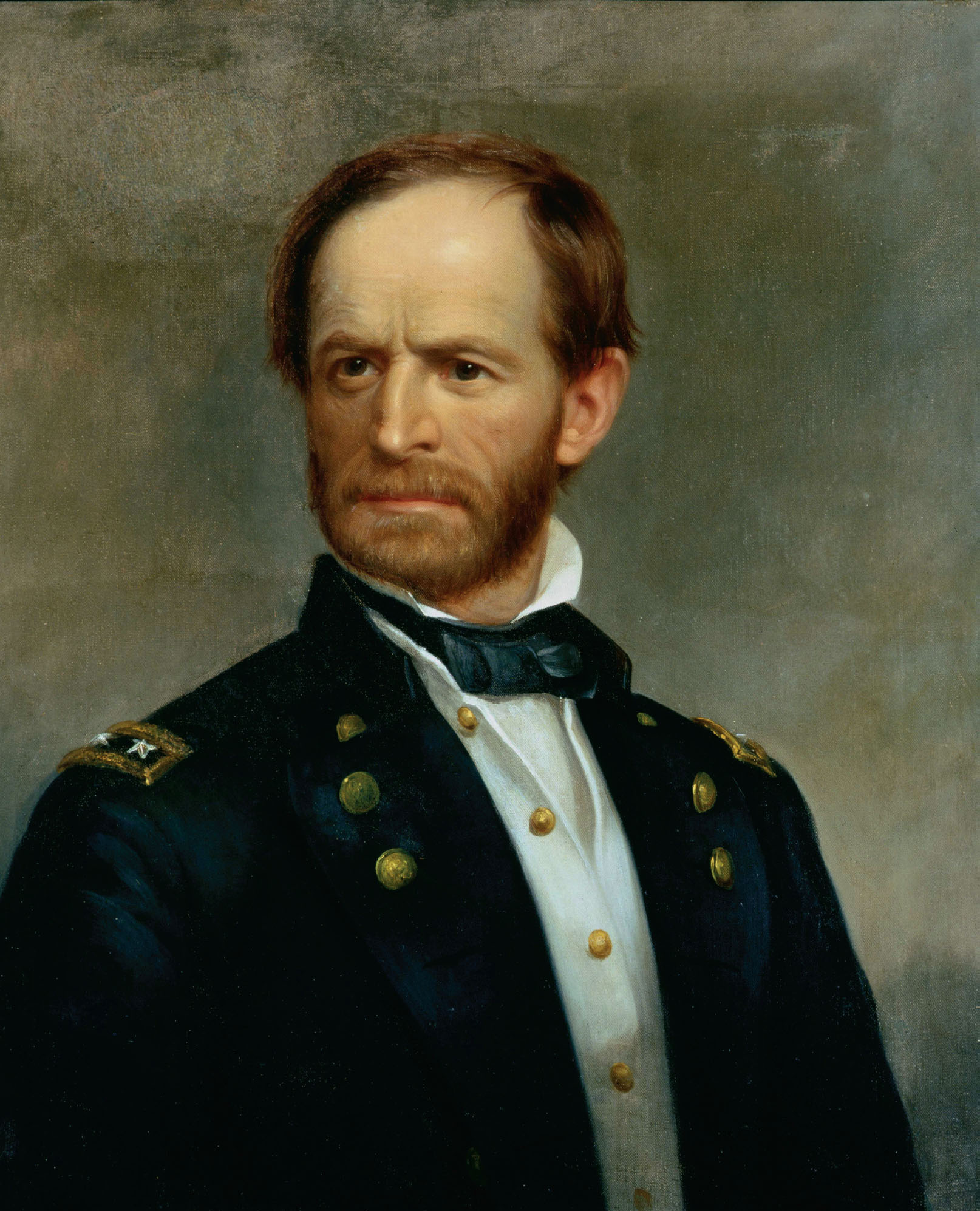

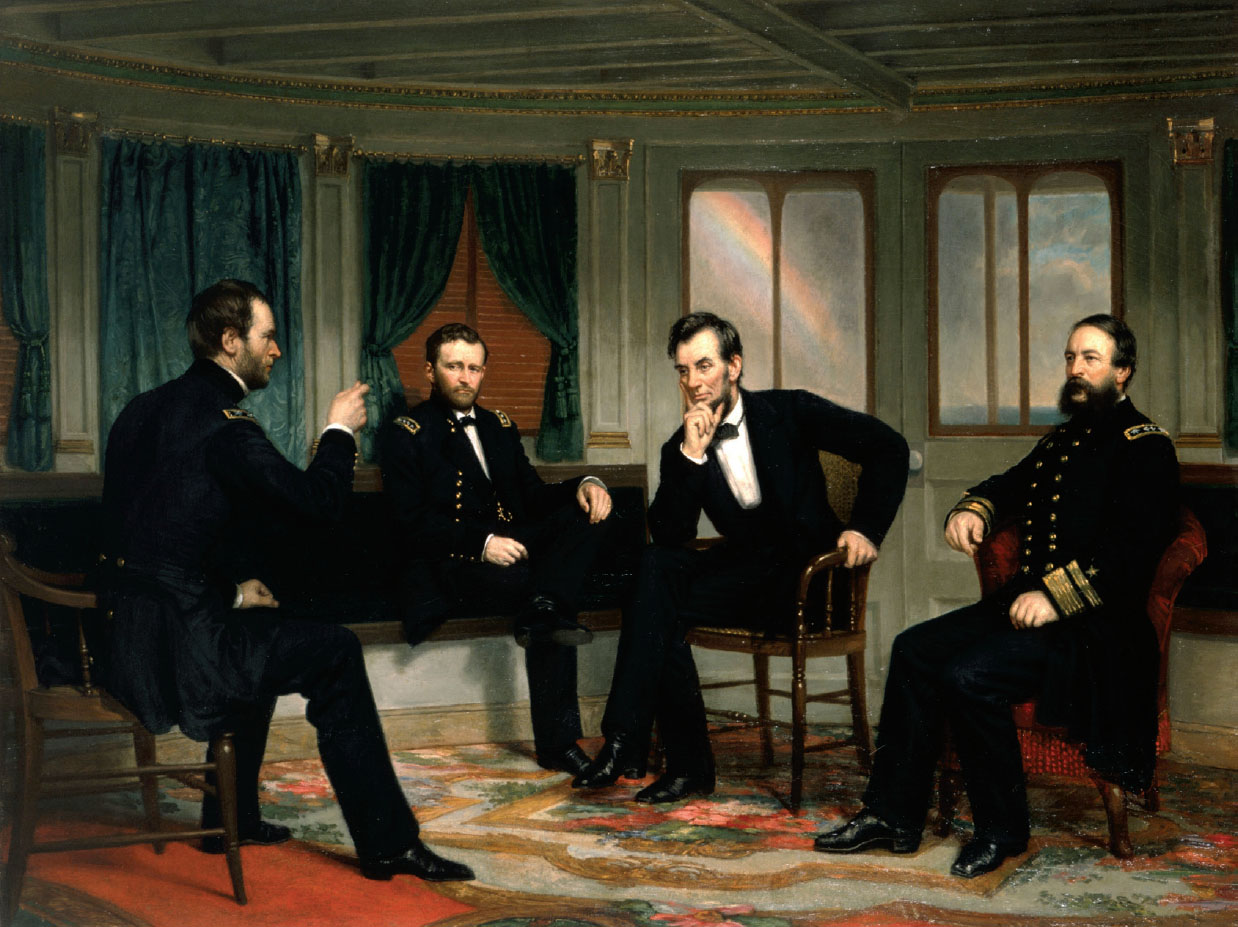

William Tecumseh Sherman, seen in this 1866 portrait by

George Peter Alexander Healy, believed, “It is only those who have never heard a shot, never heard the shriek and groans of the wounded and lacerated … that cry aloud for more blood, more vengeance, more desolation.”

While Richmond was the political center of the Confederacy, the magnificent city of Atlanta was its economic heart. It was the commercial center that kept the Confederate army supplied. Four major rail lines converged there; the munitions factories, the foundries, the factories, and the warehouses were located there. The matériel that poured out of the city kept the rebels fighting, while Georgia’s plantations kept them fed. But even more than that, Atlanta was the symbolic capital of the Southern way of life. It was the gracious place later romanticized by Margaret Mitchell in her epic Gone with the Wind: a land of sparkling white mansions tended by obedient slaves, of perfect fields and beautiful carriages, and genteel gentlemen and ladies. A place where men greeted women with a brush of their lips on a white-gloved hand.

And Sherman intended to destroy it.

In May 1864, his 110,000 men left Chattanooga, Tennessee, and marched south, initially following the railway lines. Joe Johnston’s 55,000 rebel troops were waiting for them. The outmanned and outgunned Johnston intended to block Sherman’s path by taking well-fortified defensive positions and letting the Yankees crash into them. But Sherman refused to take the bait, instead continually flanking Johnston’s army, never letting him throw a telling punch. Over and over, while a sizable force flirted with the rebel lines to hold them in position, other units would maneuver around Johnston’s flank and threaten his supply lines, forcing the Confederates to withdraw. It was an exquisite military dance, with both sides moving deftly in response to enemy jabs.

There were daily skirmishes and several pitched battles, and casualties continued to mount, but neither Sherman nor Johnston could maneuver his opponent into a compromised position. In late June Johnston made a stand at Kennesaw Mountain and an exasperated Sherman elected to fight him there. The bluecoats lost three thousand men as they vainly attempted to fight their way uphill against entrenched defenders. It was an expensive lesson that Sherman would not repeat.

Sherman faced his own problems getting supplies. The farther south he marched, the more difficult it became to protect the railway tracks on which he depended. As Johnston retreated, he destroyed bridges and tracks, but somehow Union engineers managed to repair them quickly.

In mid-July, on the same day that Union troops crossed the Chattahoochee River and took dead aim at Atlanta, a panicked Jefferson Davis sacked Johnston. “You have failed to arrest the advance of the enemy to the vicinity of Atlanta,” the orders read, “and I … express no confidence that you can defeat or repel him.” Johnston was furious, convinced that he had forced Sherman to stretch his thin supply line too far and that the North already was becoming frustrated at his lack of real progress and would elect McClellan. All he had to do was hold him outside Atlanta. Davis felt very differently; he wanted victories, and he wanted the Union to bleed.

To the great delight of Sherman and his staff, Johnston was replaced by General John Bell Hood, an able leader respected for his bravery and his aggressiveness. Hood had been badly wounded at Gettysburg and had lost a leg at Chickamauga—he had to be strapped into his saddle—and yet he continued to attack. Unlike Johnston, Sherman believed, J. B. Hood was sufficiently reckless to come out of his defensive positions and fight—even against a larger army.

The Union army moved to within eight miles of Atlanta. Rather than risking an assault, Sherman decided to cut the four railroad lines into the city, forcing the rebels to either retreat or leave their fortifications and fight in the open. Hood answered on July 20. Finding a gap several miles wide between Union forces, he attacked at Peachtree Creek, hoping to make the Yankees pay a bloody price before their reinforcements arrived. The attempt was beaten back by General Thomas. Once again, the Rock of Chickamauga stood firm; five hundred rebels were killed, more than a thousand were severely wounded, and a substantial number of prisoners were taken.

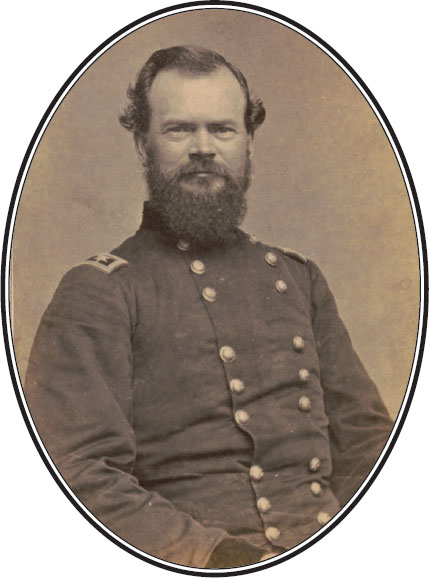

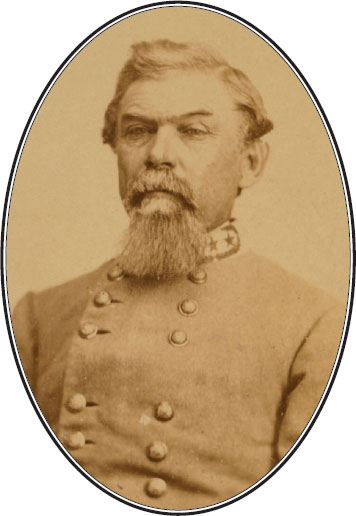

General Joe Johnston (left) was, according to General Longstreet, “the ablest and most accomplished man that the Confederate armies ever produced.” But President Davis, declaring “no confidence that you can defeat or repel [Sherman],” replaced him with the more aggressive John Bell Hood (right), who attacked and was beaten three times, essentially destroying his army’s of fensive capabilities.

Two days later, the resilient Hood made a second attempt. Leaving a sizable force in position, he marched thirty thousand men fifteen miles in the night and launched a surprise attack in the early morning light. It almost succeeded. The Battle of Atlanta was fought through the day, and the rebels made substantial gains. But the grueling night march had made coordination impossible, and before Hood’s troops could strike the Union rear to relieve the pressure, federal reserves had been sent forward to fill the gap.

During the fighting, Sherman’s subordinate and close friend, General James Birdseye McPherson, was inspecting his lines when he encountered a rebel patrol. He turned and tried to escape but was shot in the back and killed, becoming the highest-ranking federal officer to die in battle. Confederate captain Richard Beard asked a captured Union officer, Colonel R. K. Scott, to identify the slain man. “Sir, it is General McPherson,” Scott replied. “You have killed the best man in our army.”

Shouting, “Come on boys, McPherson and revenge!” the Yankees fought back. Sherman ordered his artillery to shell rebel positions, decimating their ranks. Sherman’s superiority in men and guns proved too much and Hood retreated behind his defenses, as Sherman had predicted.

Hood still had some fight left in him. On the twenty-eighth of July, as Union troops circled the city to cut off the last remaining rail link, the Macon and Western coming from Savannah, the rebels attacked one last time at Ezra Church. It was a hopeless effort, and the Yankees poured murderous fire into the Confederate lines. “This battle discouraged our men badly,” wrote a Confederate officer, “as they could never understand why they should have been sent in to such a death trap to be butchered up with no hope of gaining anything.”

It was reported that Sherman wept openly when he learned that one of his most respected young commanders, the thirty-five-year-old general James B. McPherson (above), had been killed.

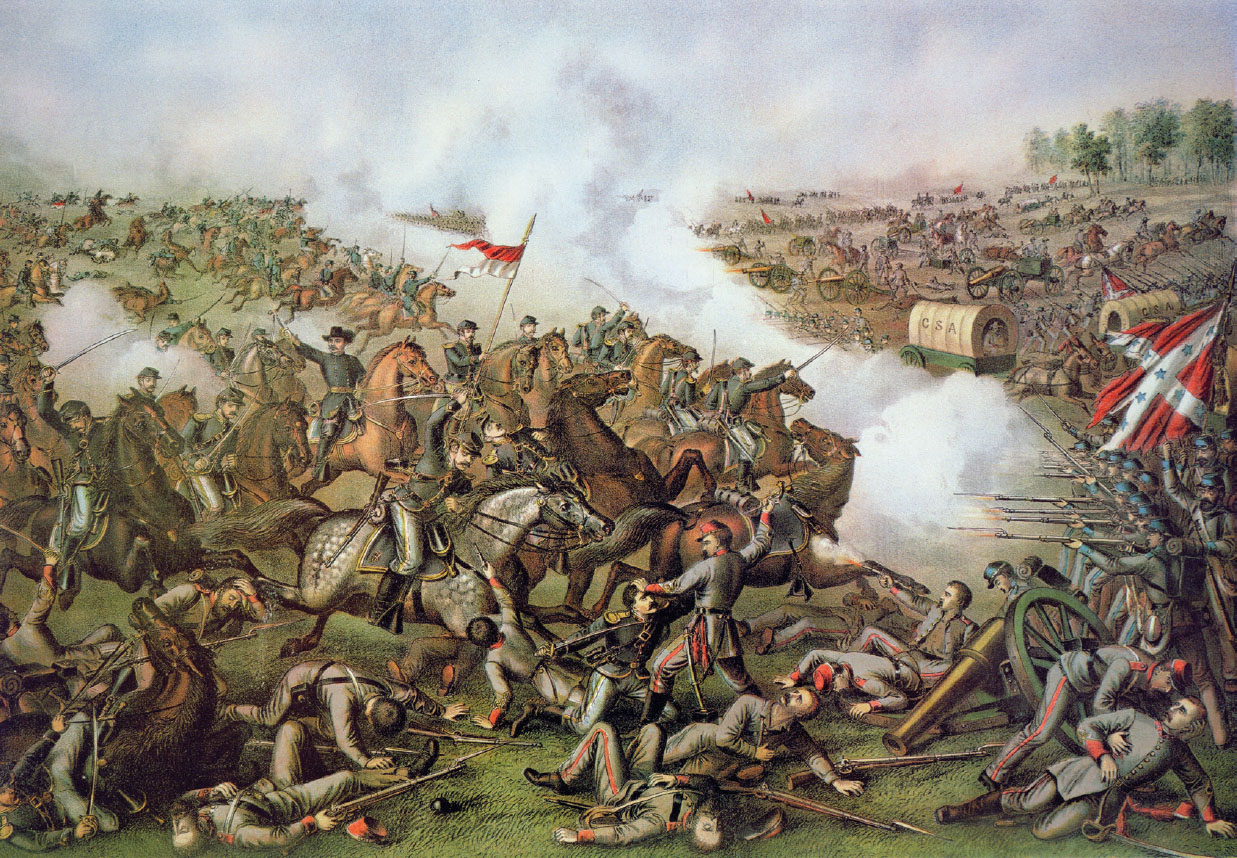

This is a detail from the cyclorama The Battle of Atlanta. The entire painting-in-the-round, which created an experience of being at the scene, was 42 feet high and 358 feet in circumference, the largest painting in the country. It depicts a cavalry fight at Decatur on July 22, in which rebel troops have broken through Union lines and are resisting counterattacking troops. This cyclorama was introduced in Detroit in 1887 before being installed in Atlanta.

In less than a week Hood had taken more casualties than Johnston had suffered throughout his entire campaign. Hood had given the Confederacy the fight it had wanted, and his army had lost an estimated sixteen thousand men. Sherman’s army had been badly wounded, too, but he had the ability to replace those men and arms.

When Sherman departed Chattanooga, Atlanta had been a bustling city of about twenty thousand residents, more than a quarter of them working in military-related jobs. But as his army approached, thousands of civilians fled the city, reducing its population by more than half. So when Union artillery blasted the city for thirty-seven consecutive days, there were fewer civilian casualties than might be imagined.

After taking the beating at Ezra Church, Hood had hunkered down inside the city, his army manning the more than twelve miles of defensive earthworks that encircled Atlanta. The network of redoubts, rifle pits, dugouts, and twisting barricades had taken a year to construct, much of the labor done by slaves hired from their owners. To Sherman’s great disappointment, Hood had finally accepted the wisdom of Johnston’s defensive strategy.

Sherman understood that a direct attack on those fortifications was hopeless, that “an assault would cost more lives than we can spare.” Instead he set out to sever the last supply lines into the city, intending to choke the city into submission. But his own supply lines were already stretched too far; moving around the city to attack those rail lines would force him to operate deep in enemy territory without sufficient food and munitions. That was not a risk he was willing to take. Yet.

To force the issue, Sherman increased the daily bombardment. At times more than five thousand shells a day landed inside the city. His objective, he wrote to one of his commanders, was simple: “make the inside of Atlanta too hot to be endured.… One thing is certain, whether we get inside of Atlanta or not, it will be a used-up community by the time we are done with it,” adding later, “Let us destroy Atlanta and make it a desolation.”

As the presidential election came closer, and with it the likelihood that Lincoln would be defeated, both Grant and Sherman were stalled. The fighting continued sporadically; men died or were wounded every day in skirmishes. Those people remaining in Altlanta burrowed shelters in their backyards and railroad embankments or hid inside steel bank vaults. During lulls in the shelling they kept up a pretense of normal life. Newspapers were published daily. For minutes at a time everything appeared normal—and then the whine of an incoming shell would trigger a mad scramble for the safety of the earth.

The residents in Richmond also created an illusion of normal life. Men and women promenaded in Capitol Square and attended “starvation parties,” which were little different from prewar parties except that no food or beverages were served. At these parties they savored “the feast of reason and the flow of soul.” As the Richmond Daily Dispatch would later report, “Richmond laughed while it cried, and sang while it endured, and suffered and bled.” Incredibly, even in the most challenging moments their confidence in Uncle Bob, as they referred to Lee, never wavered.

In late August, Sherman’s patience ran out. The dangers of waiting with his supply lines exposed continued to grow. He finally decided to take the gamble. The artillery barrage stopped suddenly on August 26. Scouts sent out by Hood reported that the Yankees were gone. Their camps were abandoned. For a full day the Confederates believed that Sherman had fallen back across the Chattahoochee. People cautiously ventured out of their shelters; military bands played in celebration. Hood’s staff reportedly was “gleeful.”

But rather than withdrawing, sixty thousand Union troops had marched west, far beyond the rebel fortifications, then turned south fifteen miles outside the city. Even before Hood fully appreciated the threat, the Yankees had successfully cut off the Atlanta and West Point Railroad. To make certain that the railroad tracks could not be reused, Union soldiers heated them until they were malleable; then they twisted them, sometimes bending them around trees. These steel loops eventually became known as “Sherman’s neckties.” Atlanta’s last lifeline was the Macon and Western Railroad, which ran near the small towns of Rough and Ready and Jonesborough. The rebels raced to protect it.

After occupying Atlanta in September 1864, Sherman collected sufficient supplies for his march across Georgia to Savannah. When he departed in early November, he ordered anything that might aid the rebels when they reoccupied the city to be destroyed. This is what was left of the railroad depot.

Sherman had beat them there and built log parapets. Hood did not know the size of the Union forces or that his troops were so greatly outnumbered. The rebels fought valiantly, throwing themselves in waves into the Union guns, and they had some success. But after two days of hard fighting, the Battle of Jonesborough ended.

Atlanta was completely cut off.

In the middle of the night of September 1, the city was rocked by massive explosions. A giant fireball rose into the air. Then another, and another. The thunderous blasts were heard by Union troops fifteen miles away in Jonesborough. As a witness later wrote, “The very earth trembled as if in the throes of a mighty earthquake. The houses rocked like cradles, and on every hand was heard the shattering of window glass and the fall of plastering and loose bricks.” Every building within several hundred yards was leveled, and fires began spreading.

It took some time for Sherman to confirm his hopes: Hood was destroying his supplies, including eighty-one railroad boxcars crammed with food, medical supplies, and eighteen tons of ammunition, enough to have sustained a fight for weeks. Sherman’s officers pleaded with him to press his advantage and crush Hood’s army, but Sherman refused, believing that destroying the railroad tracks had greater long-term strategic value.

As General Hood prepared to abandon Atlanta, he discovered that an officer “too much addicted to drink of late to attend to his duties” had failed to remove vast stores of supplies and ammunition. Rather than leave them for Sherman, he ordered them destroyed. It took more than five hours to blow them up. Seen here is what was left of the munitions train and a rolling mill.

Robert Knox Sneden’s beautifully hand-drawn map shows the rebel fortifications that completely ringed Atlanta.

Hood’s army successfully slipped out of Atlanta. A day later Sherman’s troops entered the city. They were greeted jubilantly by the black population that had remained behind. While certainly a significant military victory, perhaps more important was the fact that the capture of Atlanta is credited with saving Lincoln’s presidency. With the Confederacy reeling, there was little McClellan could offer voters that Lincoln was not poised to deliver.

Three days after taking control of the city, Sherman ordered the remaining residents to leave: “I have deemed it to the interest of the United States that the citizens now residing in Atlanta should remove,” he wrote, “those who prefer it to go south and the rest north.” This first order barely gave a hint of the cold, efficient, and brutal way Sherman was to fight throughout the South.

This illustration, Exodus of Confederates from Atlanta, first appeared in the 836-page Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War: Contemporary Accounts and Illustrations, published in 1866.

Sherman was aware that his stay in Atlanta would be brief. The longer he remained in one place, he knew, the more difficult it would be to protect his lines of supply and communications. As many as half of his troops were necessary to keep those lines open. So he did not want the additional responsibility of feeding the civilian residents of the city. As a gentleman and an officer, he actually appealed to General John Bell Hood, whose army was regaining its strength south of the city, to assist the few thousand men and women who would be forced to leave the city. Hood grudgingly complied, responding that this order to evacuate “transcends, in … ingenious cruelty, all acts ever brought to my attention in the dark history of war.” After several other bitter exchanges, Hood warned defiantly, “We will fight you to the death. Better die a thousand deaths than submit to live under you or your Government and your negro allies.”

When the city leaders appealed, pointing out that the lives of children, the elderly, and even pregnant women would be at stake, Sherman was unmoved. He fully understood the “distress that will be occasioned” but responded that the only avenue to peace was surrender and reunion. “We don’t want your Negroes or your horses, or your houses or your land, or anything you have,” he wrote, “but we do want and will have a just obedience to the laws of the United States. That we will have, and if it involves the destruction of your improvements, we cannot help it.”

The Union army transported those civilians out of the city, leaving them near Hood’s encampment. One of these people, a young woman named Mary Gay, wrote that they “were dumped out upon the cold ground without shelter and without any of the comforts of home.”

William T. Sherman had embarked on a path that was to make him one of the most beloved, controversial, and reviled men in American history.

“Cump,” as he was known to friends, was one of eleven children of Ohio lawyer and state supreme court justice Charles Sherman. He was eleven years when his father died, leaving his family in financial ruin, and he went to live with the family of Ohio senator Thomas Ewing. Senator Ewing obtained a place for him at West Point and he graduated sixth in the class of 1840. His military career was undistinguished; he fought against the Seminoles in Florida but missed the career-making opportunity to fight in the Mexican-American War enjoyed by many of his classmates. In 1850, he married Senator Ewing’s daughter in a lavish wedding attended by President Zachary Taylor, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster. While stationed in San Francisco in 1848, he was present when vast gold deposits were discovered along the Sacramento River—he even helped write the official letter confirming the find—and yet was unable to profit from it. With such prominent connections, his prospects seemed bright, so he resigned his commission in 1853 and became a gentleman banker in San Francisco. Many of his friends from West Point and the military entrusted him with their investments, but when the gold rush bubble burst in 1857, his bank collapsed and those funds were lost. He cashed in much of his own fortune to reimburse men like Braxton Bragg and George Thomas, both of whom would join him as celebrated Civil War generals.

But like Grant, who was to become his close friend, there was little about Cump Sherman’s early life that would predict the way his tactical skills and tenacity, his courage, and his determination would enable him to rise and succeed under the most challenging circumstances. Nor that he would be both idolized as a war hero and vilified as a war criminal.

Sherman was serving as the first superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning and Military Academy, later to become Louisiana State University, when civil war threatened. While the Southerners around him boasted of their loyalty to the South and predicted that the North would not fight for the slaves, he tried to warn them that a civil war would be long and costly. For him the argument was not about slavery but rather about the cost of secession. He told a friend, the Virginia professor David Boyd, “This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization.… You are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical, and determined people on Earth.… You are bound to fail.” When Louisiana joined the Confederacy, he resigned his post, telling the governor, “On no earthly account will I do any act or think any thought hostile … to the … United States,” and moved to Missouri.

Sherman visited Washington, where his brother, the Republican senator from Ohio John Sherman, introduced him to Lincoln. Sherman remembered being terribly disappointed that Lincoln did not share his alarm concerning the lack of preparation in the North for the coming war. Few men were as exposed to the folly and to the lack of appreciation for the consequences of this war, on both sides, as Cump Sherman.

As the war began, Sherman’s brother obtained a commission for him in the Regular Army as a colonel. After distinguishing himself at the First Battle of Bull Run, where he was grazed twice, he was promoted to brigadier general and given command of the Department of the Cumberland in Kentucky. Rather than being satisfied at his rapid progress, he was furious. He didn’t want the responsibilities of command; he drew unwanted attention to himself by complaining about a lack of support and the shortcomings of his own troops, and he greatly overestimated the number of enemy soldiers in his region. Eventually, at his own insistence, he was relieved of his command. He suffered through a difficult period, admitting to contemplating suicide. His wife, Ellen, called Nellie, requested help from Senator Sherman, referring to “that melancholy insanity to which your family is subject.” The Cincinnati Commercial added to his public humiliation when it reported he had gone insane.

His career was saved several months later by General Henry Halleck, who assigned him to Grant’s command. He displayed his courage at Shiloh, where he was wounded twice and had three horses killed under him. He and Grant became fast friends, especially after Sherman convinced him not to resign. It was beyond improbable that these two misfits would have found each other and provided the emotional support that made such a difference to the army and the nation. As Sherman once explained, “General Grant is a great general, I know him well. He stood by me when I was crazy and I stood by him when he was drunk; and now, sir, we stand by each other always.”

After being put in command of the Union army, Grant gave the Military Division of the Mississippi, the army west of the Appalachians, to “Uncle Billy,” as his men called him. As Sherman wrote in his memoir, when the two commanders set out with their great armies in May 1864 to attack Richmond and Atlanta, he sent Grant a note outlining his strategy for ending the war. “If you can whip Lee and I can march to the Atlantic I think ol’ Uncle Abe will give us twenty days leave to see the young folks.”

By September, Sherman had done his part—he had captured Atlanta. And he then began his legendary march to the Atlantic. Sherman’s five-week campaign is unmatched in American military history for its daring, its success, and its brutality. With Confederate general Nathan Forrest continuing to peck at his communication and supply lines, Sherman decided on an extraordinary strategy: he would cut loose completely. He determined to take his sixty-two thousand troops through Georgia to the sea without supplies or communications with Washington. It was as risky as it was bold, and Lincoln was skeptical. Grant convinced the president that let loose of his constraints, Sherman could deliver on his promise to “make Georgia howl.” Lincoln finally agreed, asking only that the campaign be delayed until after the election.

General Hood’s Confederate army had abandoned Georgia and gone west, into Tennessee and Alabama, daring Sherman to pursue him. Sherman resisted that temptation, sending General Thomas to Nashville to hold Hood there, thus leaving the entire state of Georgia open to him. With the exception of some cavalry and state militia, there were no rebels to prevent Sherman from “smashing Georgia.”

Improbably, with his army staggered and his people starving, Jefferson Davis continued to insist that the war might still be won. In a late-September speech in Macon he compared Sherman to Napoleon, claiming, bizarrely, that “the fate that befell the army of the French Empire and its retreat from Moscow will be reacted. Our cavalry and our people will harass and destroy his army as did the Cossacks that of Napoleon.… When the war is over and our independence won, (and we will establish our independence,) who will be our aristocracy? I hope the limping soldier.… Let us with one arm and one effort endeavor to crush Sherman.”

On November 15, 1864, Sherman left Atlanta with 62,204 men, twenty-five hundred wagons, and five thousand head of cattle. His march, illustrated here on Sneden’s map, was hampered as much by “General Weather” as by rebel troops. Rain and snowstorms turned roads into mud and slowed them for much of the 285-mile march. Along the way, Sherman wrote, slaves were “simply frantic with joy,” but any man incapable of fighting was discouraged from joining the march. When Savannah surrendered on December 21, Sherman suffered only an estimated three thousand casualties.

Throughout September and October Sherman made meticulous plans for this march to the sea. The army was to be entirely dependent on its own resources. There could be no reinforcements, no supplies, no orders from Washington given or received. Relying on census records, he mapped a route that would provide sufficient food and forage for his troops and their animals. His troops would travel as light as possible, living off the land. Each regiment would have a single supply wagon and a single ambulance. All noncombatants, the wounded, and the sick were sent to the rear. Every wagon was filled with as much ammunition and stores as it could carry. Following Lincoln’s landslide victory on November 8, he prepared his army to depart. But as they readied, Sherman gave one final order: burn Atlanta.

The images of Atlanta burning created for the film version of Gone with the Wind are seared into American memory. The impression held by most is that Sherman set fire to the city to punish the South for starting the war, and while there certainly was some truth to that, in fact his motives were more complex. He intended to make life as harsh as possible for Southerners, believing that destroying their morale was necessary to drive Jeff Davis to the peace table. But he was also determined that Atlanta would never again be capable of supplying tools to the Confederate army. For that reason he did not set fire to the residential areas of the city but rather its industrial district, which consisted of the railroad station, factories and machine shops, tool sheds, and other buildings that might be of value to the military.

Although history blames Sherman for the destruction of Atlanta, the city had already been decimated by the relentless shelling and then the fires that began when Hood blew up his munitions. Sherman simply added to the carnage. As the army marched out of the city on November 16, proudly singing “John Brown’s Body,” one officer took a last look back and later remembered, “Nothing was left of Atlanta except its churches, the City Hall and private dwellings. You could hardly find a vestige of the splendid railroad depots, warehouses, etc. It was melancholy, but it was war prosecuted in deadly earnest.”

And then Sherman’s army seemingly disappeared. “I will not attempt to send carriers back,” he had telegraphed Grant before cutting those wires, “but trust to the Richmond papers to keep you well advised.” For the next five weeks, no one in Washington or, it appears, Richmond, knew precisely where the Union army was heading.

Sherman divided his army into two wings of roughly equal size, marching generally in parallel but remaining twenty to forty miles apart. One wing seemed to be going toward Macon, the other in the direction of Augusta. But they marched through the South like locusts, taking whatever they needed, burning what was left, and leaving behind rubble, fear, and bitterness. As Harper’s Weekly reported in December, apparently based on stories from Southern newspapers, “destroying as he goes, he carries a line of fire straight across the surface of the rebel section, cutting a terrible swath to the sea. General Sherman does not play at war.”

Every farm animal was taken; the plantation fields were stripped bare and stored crops were seized. Sherman’s orders against pillaging were often disobeyed as soldiers ransacked homes and took whatever they wanted, sometimes leaving “Sherman sentinels,” as the forlorn chimneys of burnt-out homes became known. There were occasional skirmishes with rebel cavalry and militia, but they didn’t even slow the march—nothing slowed it. Sherman’s “scorched earth” policy horrified the Confederacy; it was beyond the accepted rules of warfare. Sherman paid no attention, if he even heard the cries. He had set out to cut the Confederacy in half and destroy the Southern will to fight and nothing—except those sentinels—would be left standing in his wake.

This 1868 engraving depicts the burning of buildings, the destruction of railroad tracks and telegraph lines, the taking of supplies, and the freeing of slaves that were daily occurrences during the march.

Many Georgians buried or hid their provisions and valuables, sometimes disguising them as fresh graves. But often their newly freed slaves would lead the troops to these caches. As the army burned its way to the sea, a smaller force, consisting of several thousand contraband, joined and followed Sherman’s trail, praising him as a prophet who was leading them to freedom. The army hired many of these men and women as teamsters, cooks, and servants, providing the labor necessary to clear obstacles and lay roads. Others provided a more valuable service, infiltrating Confederate camps and gathering intelligence. But most of these contrabands became a burden, and caring for them eventually became a significant problem. These people refused all suggestions that they return—temporarily—to their plantations, fearing that they would be put back in chains, beaten, or killed for betraying their owners.

In one especially tragic event in early December, the ironically named Union general Jefferson Davis ordered his troops to construct a pontoon bridge across the wide and deep Ebenezer Creek. But after his fourteen thousand men had crossed, he had the bridge removed, marooning the freed slaves on the other side. As Joe Wheeler’s rebel cavalry approached, many of those people panicked and tried to ford the river. Colonel Charles Kerr witnessed a scene “I pray my eyes may never see again.… [Amid] cries of anguish and despair, men, women, and children rushed by the hundreds into the turbid stream, and many were drowned before our eyes. From what we learned afterwards of those who remained on land, their fate at the hands of Wheeler’s troops was scarcely to be preferred.” According to reports, many Union soldiers tried to help, lashing together downed trees for makeshift rafts or wading into the water themselves, but hundreds drowned in the icy waters of the creek.

Within hours, Wheeler’s cavalry got to the creek, and the mostly women, children, and elderly who had not reached the other bank were gathered up and returned to slavery.

Like only a few great military leaders, Sherman had the unshakable ability to put aside his humanity to fulfill his mission. He accepted without question that the cost of saving the most lives was the sacrifice of other lives. The freed slaves were not the only people who suffered because of this. The Confederates had established several prisoner-of-war camps. Among them was the infamous prison built in early 1864 in Andersonville, Georgia, that officially was known as Camp Sumter. Built to house ten thousand men, within months it contained more than forty thousand prisoners, effectively making it the fifth-largest city in the Confederacy. With the South already suffering shortages because of the Union naval blockade, the camp lacked food, shelter, sanitation facilities, medical supplies, and even clean water. Sweetwater Creek ran through the camp and was used for the disposal of trash and human and animal waste, for bathing, and, finally, as the sole source of drinking water. Malnutrition, scurvy, dysentery, and diarrhea plagued the camp, and eventually in excess of one hundred prisoners were dying there every day, more than twice as many as were dying in battle. In many cases bodies lay bloating in the sun for days. As one prisoner wrote forlornly, “Since the day I was born, I never saw such misery.”

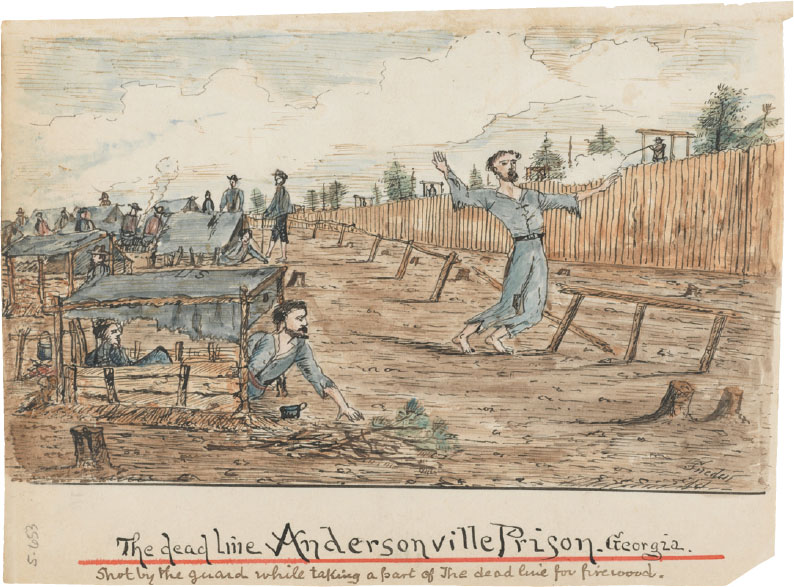

When Union soldier Robert Kellogg walked into Andersonville prison he was stunned. “Before us were forms that had once been active and erect;—stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons.” Among the horrors of the 26.5-acre prison was the “dead line,” a small fence inside the prison wall that indicated the no-man’s-land between the fence and the walls. As seen in this sketch, anyone crossing or touching the dead line would be shot.

Sherman was made aware of the deplorable conditions inside Andersonville during his Atlanta campaign. Rather than diverting his army, in July he dispatched cavalry general George Stoneman with twenty-two hundred men to attack Hood’s rail lines—agreeing that if Stoneman was successful he could attempt to liberate the prisoners at Andersonville. Stoneman encountered heavy resistance and was captured by the Confederates. Sherman did not make a second attempt.

Some historians believe that Sherman had little interest in saving those prisoners’ lives. If he had been successful, he would have been burdened with many thousands of sick and emaciated troops who could not survive on their own, forcing him either to care for them—without sufficient food or medical supplies—or continue his offensive. Splitting his army to protect them or transport them to safety at that time might have proved to be a terrible mistake.

And so the prisoners continued dying. After Sherman occupied Atlanta, which put his troops only a fair cavalry ride away from Andersonville, Confederates transferred the healthiest prisoners to other camps. Among them was Camp Lawton in Millen, a massive prison that held more than ten thousand men. It was operational for less than three months, and was then abandoned and its prisoners moved only four days before Sherman’s troops arrived. All they found there was a mass grave marked with a small wooden sign reading 650 BURIED HERE.

It is probable that this harsh treatment infuriated Sherman and his men, which provided an easy rationale for their own brutality. By the end of the war, nearly thirteen thousand Union soldiers had died at Andersonville. When poet Walt Whitman learned about this, he wrote, “There are deeds, crimes that may be forgiven, but this is not among them.” Eventually the commandant of the camp, Captain Henry Wirz, was hanged in Washington, making him the only Confederate executed for war crimes.

Sherman’s army remained out of communications with Washington for four weeks. He reached the outskirts of Savannah in early December. It was only a matter of time and casualties until he took that city. Confederate general William Hardee flooded the rice fields surrounding the city to limit access to a few defensible causeways. But he was a realist and understood that his ten thousand men could hold out only so long. After refusing Sherman’s demand that he surrender, his army abandoned the city on December 20 rather than subjecting the city to the hardships and destruction of Atlanta. Two days later a jubilant Sherman sent a telegram to Lincoln declaring, “I beg to present you, as a Christmas gift, the city of Savannah, with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition, and also about 25,000 bales of cotton.”

When Confederate general William Hardee realized he could no longer defend Savannah, he ordered a complete withdrawal in the night in an attempt to save his army. A long line of wagons crossed the Savannah River on a floating bridge, carrying as much war matériel as possible. His men followed, leaving the city open to Sherman. Hardee directed that nothing be blown up that might alert the enemy to his plan. This withdrawal was successful and may have saved the city from destruction.

The capture of Atlanta had turned the election in Lincoln’s favor; now the president hoped to put this gift to political use to help him convince Congress to pass the Thirteenth Amendment. It was a simple proposition. “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States.” But it was fraught with political consequences. A war, which was not yet done, had been fought over this idea. More than six hundred thousand men had died, and millions more had been injured over it. And yet the Union Congress had refused to pass it. The amendment had been introduced in Washington a year earlier. The Senate had passed the proposed amendment quickly, but in June 1864, House Democrats favoring states’ rights had formed a coalition with Republicans anxious about reelection. Lincoln persisted; for him passing the amendment banning slavery forever was the “fitting, and necessary conclusion” to the war.

It was a difficult fight. Some congressmen believed that passing it would actually prolong the war, making the Confederacy less likely to surrender. Others believed that even after the fighting ended, it would make reunification more challenging. Still others believed that it might be unconstitutional, that it was a decision that should be left to the states. And certainly there were racists who simply did not want black Americans to enjoy equal rights. Lincoln needed to secure about thirty additional votes. While his reputation as a statesman resonates throughout our history, when necessary he also could be a tough politician. He knew how to play the political game to achieve his objectives. As brilliantly portrayed in Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, he and Secretary of State Seward began horse trading with reluctant Democrats, offering all kinds of bribes and promises in return for votes or, for those who couldn’t vote for it, abstention. No one really knows the extent of this deal making. They supposedly twisted arms, offered government jobs, and threatened to withhold federal support for local projects. One lame-duck congressman became the ambassador to Denmark. An appointment to an open seat on the federal court in Missouri was used to lure votes.

On January 31, 1865, the House passed the Thirteenth Amendment by two votes—with eight members abstaining. Key to passage were the sixteen Democrats who joined all of the Republicans in voting for it, fourteen of whom were lame ducks. “A great moral victory,” Lincoln called it, but morals had a lot less to do with it than rewards. When the war ended, the Confederate states were forced to ratify the amendment as a condition to rejoining the Union. Fittingly, it became the law of the land in December 1865, when Georgia approved it.

While Lincoln was busy fighting for the Thirteenth Amendment and eventual freedom for all slaves, the problem General Sherman faced was right in front of him. Thousands of former slaves who had attached themselves to his army, either employed or straggling behind, had followed him to Savannah. He was preparing to march north, since there was still fighting to be done, and he wanted his army to be free of this responsibility. Lincoln sent Edwin Stanton to Georgia to help Sherman work out a solution.

In mid-January, after meeting with freed blacks in Savannah, and with the president’s approval, Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15. It was an extraordinary document. It declared that the military was confiscating from slaveholders four hundred thousand acres, about thirty miles of plantation fields and islands along the coast, and awarding no more than forty acres of land—and an army mule—between Charleston and Jacksonville to freed slaves. While the precise number of people who actually received this Sherman land is not known, estimates are as high as forty thousand people. This order also urged freed blacks to join the Union army.

This promise of “forty acres and a mule” was never fully met. After Lincoln’s assassination, President Andrew Johnson revoked the order and returned the land to its previous owners.

But this order did serve to settle thousands of freed blacks, many of whom joined the Union army and helped establish a quasi-military presence there. Sherman wasn’t done inflicting damage on the Confederacy, though. In February, his army left Savannah and turned north, marching into the Carolinas. The war had begun there four years earlier, and so it was right, they were convinced, that it end there. “I almost tremble at her fate,” Sherman wrote as his campaign continued, “but feel that she deserves all that seems in store for her.”

Sherman’s army grew in size as other units joined him, eventually numbering almost ninety thousand troops. Against that Joe Johnston could barely muster twenty thousand men. There was little the rebels could do to stop or even slow the Yankee invasion. In February, Lincoln agreed to meet a delegation for a peace conference at Hampton Roads. The two sides were brought together by the influential power broker Francis Preston Blair. The meeting lasted less than five hours; Lincoln found no need to offer any compromise. The only path to peace was reunification on Union terms, the first condition being the abolition of slavery. As the conference ended, Sherman’s army continued “marching on.”

George Healy’s 1868 oil painting The Peacemakers shows Lincoln and his military leaders at their 1865 meeting aboard the steamboat River Queen. It was here that Grant, Sherman, Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter, and the president discussed strategies for ending the war.

There were several small battles fought along the way, at Aiken, Monroe’s Cross Roads, and Bentonville, but there was little the rebels could do to stop Sherman. His army cut a wide swath through the state, leaving wreckage behind, until it reached the beautiful city of Columbia, the capital of South Carolina. Inside the city Confederate general Wade Hampton had ordered cotton bales to be collected, intending to move them to the outskirts and burn them to prevent them from falling into Union hands. Hampton knew he could not hold out against Sherman’s vastly superior army. But those bales were still stacked in the middle of the main street when he evacuated the city on February 16.

No one will ever know who set fire to Columbia, South Carolina. Whether it was flames from cotton bales set afire by retreating rebels spread by high winds, as the North claimed, or fires set intentionally by Union troops in revenge, or even whether it was started accidentally, the result was the same: about half the city was totally destroyed and Sherman was blamed for it.

The next day Sherman marched into Columbia. His men began a raucous celebration. There was considerable pillaging. A great amount of liquor was confiscated and consumed. And by nightfall the entire city was on fire.

It has never been determined who was responsible for setting those fires—although Sherman has long been blamed for it. He always claimed that those cotton bales were burning when he entered the city and were spread by gale-force winds that night. “Without hesitation,” he wrote in his official report, “I charge General Wade Hampton with having burned his own city … not with a malicious intent, or as the manifestation of a silly ‘Roman stoicism,’ but from folly and want of sense, in filling it with lint, cotton, and tinder.” He did admit that other fires might have been set by men “who had long been imprisoned there, rescued by us [who] may have indulged in unconcealed joy to see the ruin of the capital of South Carolina.”

The fires raged throughout the night. People ran down the streets desperate to escape the flames. No one knows how many people died in the night.

There is evidence that Union troops tried desperately to maintain order within the city, protect its citizens, and prevent those fires from spreading. But as General Slocum pointed out, a drunken soldier with a match on a windy night is “not a pleasant visitor.” That first night 370 soldiers were arrested, 2 were killed, and 30 more were wounded. Supposedly Sherman ordered a drunken soldier arrested and, when he resisted, had him shot.

The fires of Columbia burned out of control. “The morning dawned upon the scene of ruin,” Abbott reported. “Nearly three thousand buildings were in ashes. Little remained but a wilderness of tall, bare chimneys, blasted trees, heaps of rubbish, and smoldering ruins, to show where once had been the most beautiful, refined, and aristocratic city of South Carolina.”

Sherman left the city a smoking ruin two days later. When questioned about the fire, he confessed his real feelings. “Though I never ordered it and never wished it, I have never shed any tears over the event, because I believe that it hastened what we all fought for, the end of the War.”

Sherman’s Carolina campaign was running out of Confederates to fight. His army had traveled 425 miles in only fifty days, leaving behind similar desolation in every place they went. The war was rapidly coming to the inevitable conclusion. Outside Richmond, Grant knew it was time to force the issue.

After ten months, the rebels remained safely inside their fortifications, but their stay there was becoming increasingly difficult. Lee’s troops were worn down and his supplies were running out. He realized he had few options. He could ask Grant for terms of surrender, but he refused to consider that option without specific instructions from President Davis. Or he could leave Petersburg and join forces with Joe Johnston—together they might sustain the fight for at least another year. But doing that meant abandoning Richmond, and although that would allow him to move without restraint, it would be a devastating blow to the Confederacy and Davis would never allow it. That left only one choice: stand and fight.

To finally force Lee to come out and fight, Grant dispatched General Philip Sheridan on a sweeping maneuver below the city to cut off Lee’s remaining supply line, the South Side Railroad. As Sheridan’s cavalry rode toward the junction at Five Forks, Lee sent General George Pickett to meet him, ordering that the vital crossroads be held “at all hazards.”

The siege of Petersburg ended at Five Forks on the first of April 1865. The daylong battle ended with the Union taking control of the South Side Railroad, closing Lee’s last supply route. Lincoln happened to be at City Point, using Grant’s headquarters, the sidewheel steamer River Queen docked there, as his temporary White House. When captured battle flags were presented to Lincoln that night, he said with satisfaction, “This means victory—this is victory.” Supposedly the president’s sleep that night was interrupted by a terrible nightmare—in which he was lying in state in the White House, the victim of an assassin’s bullet.

General Philip Sheridan’s twenty-seven thousand troops crushed rebel general George Pickett’s attempt to break the siege of Petersburg. About half of the Confederates’ ten thousand men were killed, wounded, or captured. By the end of the fighting, Lee’s last supply line into Petersburg was severed and the war was racing to an end.

Grant attacked the next morning, believing that he might finally destroy Lee’s army. In the early morning confusion, Lee’s friend and adviser, A. P. Hill, was killed. “He is at rest now,” the distraught Lee said, “and we who are left are the ones to suffer.” He had no time to mourn if his army was going to survive to fight again. He had to lead the rebels out of the closing trap.

Jefferson Davis was in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond that Sunday morning. He was handed a telegram from Lee reading, “I advise that all preparation be made for leaving Richmond tonight.” Richmond had remained relatively calm throughout the siege, its citizens supremely confident that Bobby Lee would protect them. By midafternoon, as it became clear that Lee’s men were crossing the Appomattox River and abandoning Petersburg, the panic began. Government officials began burning documents. In carts and in carriages, on horseback and on foot, on boats and on barges, carrying whatever possessions they could manage, members of the government and residents abandoned the city. At eleven o’clock that night, Davis boarded a train and departed.

By that time, Richmond was burning. Earlier that day, in an effort to prevent the same type of drunken behavior that had led to the destruction of Columbia, Richmond’s city council ordered all the liquor in the city destroyed. Hundreds of barrels were poured into the streets and countless bottles were smashed. According to the Richmond Daily Dispatch, “The gutters ran with a liquor freshet, and the fumes filled and impregnated the air … straggling Confederate soldiers, retreating through the city, managed to get hold of a quantity of liquor. From that moment law and order ceased to exist; chaos came, and a Pandemonium reigned.”

Deserters broke into stores and set fires. Looters followed. The business district was leveled. The boatyard, food warehouses, two railroad stations, and the largest flour mill on the continent were reduced to rubble. The banks, hotels, and saloons ceased to exist. More than a half mile of buildings were burned into hollow shells. Anything of military value—the armory and its munitions, ironclads in the river, and several bridges—was destroyed. The munitions exploded with such force that tombstones in the cemetery nearly a mile away were knocked over. The New York Times reported that as many as fifty-four blocks and eight hundred homes were destroyed and at least forty civilians died.

On what became known as Evacuation Sunday, President Davis and his cabinet abandoned Richmond. As shown in this Currier and Ives lithograph, the fires set by retreating Confederates to deny spoils to Grant spread quickly, and ironically this time Union soldiers put them out and saved the city. Among Davis’s last acts was to name Danville, Virginia, the acting Confederate capital. A day after the city was occupied, Lincoln made a visit, an event, wrote a reporter, “too awful to remember, if it were possible to be erased, but that cannot be.”

Union soldiers occupied the city and, ironically, saved it. Fire brigades were organized and by the time Lincoln arrived a day later, most of the fires had been put out. The president walked with only a small escort through the streets, surrounded by cheering, dancing, and singing freed slaves, who fought to shake his hand, touch his clothing, or kiss his boots. The crush became dangerous. Finally, Union sailors fixed their bayonets and cleared a path for him to the Confederate White House, where he sat down behind Jefferson Davis’s desk.

Lee was on the run. But this time Grant had hold of him and wouldn’t let go. His plan was to surround the fleeing rebel army and force Lee to surrender rather than annihilating them. Down to fewer than thirty-five thousand exhausted soldiers and being pursued by a hundred thousand or more well-supplied Yankees, Lee could do little to prevent this from happening. In a series of small battles, he tried to fight his way west, toward Danville or Lynchburg, Virginia, where he might find supplies, but Grant deftly blocked him. And when Lee stopped to fight, he was thrashed: Confederate generals Richard Ewell, Custis Lee, Montgomery Corse, and Joseph Kershaw were captured at Sailor’s Creek.

The last remnant of Robert E. Lee’s once great army was struggling for survival. The troops were running out of food and ammunition. Many of them had realized that the war was over, dropped their weapons, and deserted. On the night of April 7, Grant sent Lee a note suggesting it was time to surrender. “Not yet,” Lee replied, but he did ask what terms Grant would accept.

By the ninth, Generals Sheridan and George A. Custer had cut off Lee’s escape route at Appomattox Court House. Lee had one last fight in him. That morning he tried to break through the Union lines. His troops fought their way through two lines of Union cavalry, but when a thick fog lifted they were stunned to see thousands of Union infantrymen waiting for them. Lee finally accepted that he was beaten, admitting, “Then there is nothing left for me to do but go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths.”

Grant and Lee agreed to meet early in the afternoon of April 9, 1865, at the home of Wilmer McLean. Four years earlier McLean had lived in Manassas, close enough to Bull Run to watch the fighting from his front lawn. Sickened by the combat, he had sold that house and moved somewhere safe—near Appomattox, and the war had followed him to his front parlor.

Grant and Lee actually had met for a few moments once before, during the Mexican-American War. Grant remembered being impressed by Lee’s perfectly groomed appearance; Lee remembered the meeting but could not picture the usually disheveled Grant. They arrived at this conference true to those memories, Lee in a sparkling new uniform, carrying his sword in a jewel-studded hilt; Grant in an ordinary private’s sackcoat bearing the epaulets of his rank, his boots and pants muddied. They exchanged pleasantries; then Lee asked the terms of surrender.

This print, probably published in 1866, shows Grant and Lee meeting on a road at Appomattox to discuss the terms of surrender. The fact that this never took place did not stop competing publishers from issuing lithographs to commemorate it. In fact, Lee had proposed meeting Grant on the old stage road to end the war. Grant did not reply, but Lee rode to the point. He was joined there by a Union officer who delivered a note from Grant, explaining that the general had no authority to talk about peace—he could only accept a surrender. Lee hesitated, considered the consequences, then agreed.

Unconditional Surrender Grant, as he was so well known, in fact offered extraordinarily lenient conditions. The fighting would end; the officers and men would go home and the Confederate army would cease to exist. The officers would be permitted to keep “their private horses or baggage.” Lee pointed out that rebel troops owned their horses and mules and requested that they be allowed to keep them as they would be needed on their farms. Grant agreed. Lee nodded his acceptance and said, “This will have a very happy effect on my army.”

Grant’s compassion was evident. As copies of the agreement were being drafted, he ordered twenty-five thousand rations sent immediately to the rebel troops, who had not eaten in several days. Later he admitted, “My own feelings … were sad and depressed … at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though the cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought.”

Lee’s surrender at the McLean house in the village of Appomattox Court House remains one of the most celebrated events in American history. This historically accurate oil painting by Tom Lovell was commissioned by National Geographic magazine in 1965 to honor the centennial of the end of the war. A footnote: On the far right Lovell depicted General George Custer, who was not actually in the room at the time of the surrender.

An embittered Jefferson Davis accepted the necessity of Lee’s surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, although it would be weeks before all the combatants finally left the battlefields. General Johnston officially surrendered the feeble Army of Tennessee and many smaller garrisons to Sherman on April 26; the last fighting took place on Palmito Ranch in Texas on May 11 and 12, and the last rebels to lay down their arms were the Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, and Osage Battalion on June 23.

The final toll was staggering. While the precise number of Union and Confederate soldiers who died from all causes in the war has never been accurately determined, it may be as high as 850,000 men, with at least twice that many wounded.

The heroes who led the Union to victory were amply rewarded in the next decades and helped shape the future of America in ways that still resonate. Among them, Grant would become the eighteenth president of the United States. Sherman probably could have secured the Republican nomination if he had wanted it, but he did not. Instead, he is remembered in political history for his declaration, “I will not accept if nominated and will not serve if elected.”

A ceremonial laying down of arms and flags took place on April 12, exactly four years after the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, at Appomattox Court House. By this time Lee was on his way back to Richmond and Grant to his headquarters at City Point, so General Joshua L. Chamberlain, the hero of Gettysburg, was assigned to receive the formal surrender. As the Confederate soldiers marched before the victors to lay down their weapons and unit flags, Chamberlain ordered his men to “shoulder arms,” a battlefield salute. It was considered a noble gesture of respect.

There were great shows of emotion. On several occasions rebel soldiers broke ranks, walked over to the growing pile of unit flags, “and pressed them to their lips with burning tears,” wrote Chamberlain. And then, he continued, “every token of armed hostility having been laid aside, and the men having given their words of honor that they would never serve again against the flag, they were free to go … and by nightfall we were left there at Appomattox Courthouse lonesome and alone.”

Wilmer McLean, the owner of the house in which the surrender was signed, had been a successful merchant and sugar smuggler during the war, but with the end of the war his Confederate money was worthless. He defaulted on loans secured by the property, which was auctioned off and sold for $1,250 in 1872.

On April 10, Washington was awakened to an extraordinary five-hundred-gun salute celebrating Lee’s surrender. But by that time Jefferson Davis had escaped. Rumors were that he hoped to reach safety in Texas, or a foreign nation, and form a government in exile. He remained on the run for six weeks. After Lincoln’s assassination, he was believed to have participated in that plot, and large rewards were offered for his capture. He finally was captured in rural Georgia. As apparently he was wearing his wife’s overcoat and his head was covered with a black shawl, the story spread quickly that he was caught disguised as a woman. He was widely ridiculed. Numerous prints were published showing him in skirts and a bonnet. Songs were written and sung, giving birth to a legend that never died.

Davis was imprisoned at Fort Monroe, in Hampton, Virginia, for more than two years, before he was released without a trial. He eventually regained love and respect in the South, but in the North he would always be remembered as the leader of the bloody war, who was finally captured wearing a hoop skirt.