1

The Empress of Ireland Sails to Her Doom

ANOTHER TOLL OF THE SEA—THE EMPRESS SAILS FROM QUEBEC—THE HOLIDAY HUMOR OF THE PASSENGERS—CAPTAIN KENDALL WARNED OF FOGS—THE STORSTAD SIGHTED—FOG SUDDENLY SETTLES—THE STORSTAD CRASHES INTO THE EMPRESS—INJURY ON STARBOARD SIDE—A MORTAL BLOW—WIRELESS CALLS FOR HELP—HUNDREDS DROWN IN CABINS—NO TIME TO ROUSE PASSENGERS—LIFEBOATS LAUNCHED IN RECORD TIME— THE EMPRESS GOES DOWN

Once again an appalling sea disaster comes to remind us that no precautions man can take will make him immune against the forces that nature, when she so wills, can assemble against him. It is a truism to say that the most recent marine disaster was preventable. An accident suggests the idea of preventability. The Empress of Ireland was equipped with modern appliances for safety. She had longitudinal and transverse watertight steel bulkheads and the submarine signaling and wireless apparatus. She was being navigated with all the precaution and care which the dangers of the course and the atmospheric conditions demanded. The Storstad had been sighted and signaled. The Empress was at a standstill, or slowly moving backward in response to a hasty reversal of the engines. Nothing apparently that those responsible for the lives of their passengers could do to safeguard those lives was left undone, and yet hundreds of people perished miserably.

The Empress Sails from Quebec

Proudly the Empress of Ireland, under the command of Lieutenant Henry George Kendall of the Royal Navy Reserves, moved from her dock at Quebec, about half past four on the afternoon of Thursday, May 28, 1914, bound for Liverpool. Amid scenes that are ever new and full of deep feeling to those who are taking their leave or bidding Godspeed to dear ones, the majestic ship began what her hundreds of lighthearted passengers anticipated as a bon voyage. The last “Goodbye, and God bless you!” had been said; the last embrace had been bestowed; the last “All ashore that’s going ashore” had been called out; the last home stayer had regretfully hurried down the gang board; and then, while hands, hats, and handkerchiefs were waved, with the ship’s band playing a solemn hymn, distance grew apace between the Empress and the land.

The Holiday Humor of the Passengers

Fainter and fainter the crowd on the dock appeared to the passengers on board, until finally the dock itself was lost to view as the graceful vessel gained headway. Some of the passengers remained long at the ship’s rail, held by the fascination of the water, which seemed swiftly to approach, and as swiftly to move away. Others, singly or in groups, left the rail to arrange their belongings in their staterooms, to inspect the magnificence of the vessel’s equipment, and to accustom themselves to their new surroundings.

Twilight settled without dampening the gay humor of the throng. The first meal on board was eaten with a relish which only the occasion could impart, and the passengers disposed themselves for the full enjoyment of the evening.

Captain Kendall Warned of Fogs

Captain Kendall had been warned of the prevalence of fogs in the lower river, and information had reached the liner also that there were forest fires in Quebec which were throwing smoke blankets over the St. Lawrence. Having experienced such conditions before, the commander of the Empress, while quite unalarmed, took the usual precautions.

As night came on he reduced the liner’s speed. The night was still clear when the incoming Alsatian passed so closely that her passengers had a fine view of the big Canadian Pacific Railway ship, which showed beautifully and majestically as she swung by with her decks blazing with electric lights.

Captain Kendall stopped his ship at Rimouski, a town of 2,000 inhabitants, on the New Brunswick shore, about 180 miles northeast of Quebec as the channel flows. It is a mail station, the last outpost of the Dominion mail service. Bags of mail were loaded aboard, and the Empress moved steadily out into the broad river.

At this point the St. Lawrence, leading into the inland sea, which is the Gulf of St. Lawrence, is thirty miles wide. The channel runs about ten miles from the New Brunswick shore and about twenty miles from the Quebec shore.

At midnight the tide was running in strongly. The weather was cold and there was a piercing sting to the air. The mercury had fallen to just above the freezing point. Few passengers were stirring after midnight. It was too cold on deck to make late vigils pleasurable. There were a few parties in the smoking room at bridge and poker, but the great majority of the passengers were in their berths.

The Storstad Sighted

At half past one o’clock Friday morning the Empress reached Father Point, where the pilot was dropped. The vessel then proceeded at full speed. After passing the Cock Point gas buoy, Captain Kendall sighted the Norwegian collier Storstad. To quote from his own story, as he has told it in another chapter: “The Storstad was then about one point on my starboard bow. At that time I saw a slight fogbank coming gradually from the land and knew it was going to pass between the Storstad and myself. The Storstad was about two miles away at the time.

Fog Suddenly Settles

“Then the fog came and the Storstad lights disappeared. I rang full speed astern on my engines and stopped my ship. At the same time I blew three short blasts on the steamer’s whistle, meaning ‘I am going full speed astern.’ The Storstad answered with the whistle, giving me one prolonged blast. I then looked over the side of my ship into the water and saw my ship was stopped. I stopped my engines and blew two long blasts, meaning ‘my ship was under way but stopped and has no way upon her.’ He answered me again with one prolonged blast. The sound was then about four points upon my starboard bow. It was still foggy. I then looked out to where the sound came from. About two minutes afterward I saw his red and green lights. He would then be about one ship’s length away from me.

The safety of the St. Lawrence has long been the subject of debate. Certainly it has certain natural features which make it dangerous at some seasons of the year; and of course lack of knowledge of its waters and the absence of aids to navigation were the cause of wrecks in the early stages of its navigation. But the same might be said of any other great route of trade; and there can be no question whatever that the various governments of Canada have for many years been wide-awake to adopt means of protecting mariners on this greatest water route into the heart of the American continent. Today, so great has been the progress made, that it is a common opinion of shipping men that it is almost as safe to navigate the ship channel up to Montreal by night as in the full light of day.

The Storstad Crashes into the Empress

“I shouted to him through the megaphone to go full speed astern as I saw the danger of collision was inevitable. At the same time I put my engines full speed ahead, with my helm hard aport, with the object of avoiding, if possible, the shock. Almost at the same time he came right in and cut me down in a line between the funnels.”

Captain Thomas Andersen, who commanded the Storstad, gives a different explanation of the approach of the two ships. According to his version, which is given elsewhere under his own name, “The vessels sighted each other when far apart. The Empress of Ireland was seen off the port bow of the Storstad. The Empress of Ireland’s green or starboard light was visible to those on the Storstad. Under these circumstances the rules of navigation gave the Storstad the right of way. The heading of the Empress was then changed in such a manner as to put the vessels in a position to pass safely. Shortly after a fog enveloped first the Empress and then the Storstad.

“Fog signals were exchanged. The Storstad’s engines were at once slowed and then stopped. Her heading remained unaltered. Whistles from the Empress were heard on the Storstad’s port bow and were answered. The Empress of Ireland was then seen through the fog close at hand on the port bow of the Storstad. She was showing her green light and was making considerable headway.

“The engines of the Storstad were at once reversed at full speed and her headway was nearly checked when the vessels came together.”

Injury on Starboard Side

The horrible fact, about which there can be no dispute, is that the Storstad crashed bow on into the side of the big Canadian liner, striking it on the starboard side about midway of its length. The steel-sheathed bow of the collier cut through the plates and shell of the Empress and penetrated the hull for a distance of about twelve feet, according to the best testimony.

The water didn’t flow in. It rushed in. From such stories as could be gathered from survivors and from members of the crew, it appears that Captain Kendall and his officers did all that was humanly possible in the fourteen minutes that the Empress hung on the river.

Captain Kendall said that he rang to the engine room for full speed ahead, with the object of trying to run ashore and save the passengers, but almost immediately after the engines stopped and the ship began to list rapidly. The captain of the Storstad declares that it was this action of Captain Kendall that prevented him from holding the bow of the Storstad in the gaping hole it made and that it was the Empress herself, with the way upon her, following the order “full steam ahead,” which drew away from the Storstad, bending the collier’s bow out of the great gash in the liner’s side, and disappeared in the fog. What further damage may have been done as the vessels parted no one seemed to know certainly.

Fought for Life in Darkness

Instantly, it seemed as though there was a nightmare of sounds, cries of fear and agony that were too awful to be real. All lights went out almost at once. More than 1,400 persons were fighting for life in the black dark; yet for the most part the flight was not one of panic, but grim determination to find, if possible, some means of safety.

Wireless operator Bomford and others who managed to win a way to the top deck saw scores leap into the sea. They saw hundreds trying to crawl up decks that were sloping precipitously, lose their balance, and fall backward into the rising water. Passengers who couldn’t get to the few lifeboats in time seized chairs, anything loose they could find, and leaped into the river.

Very many persons perished in the cold water while clinging to bits of wreckage and praying for help.

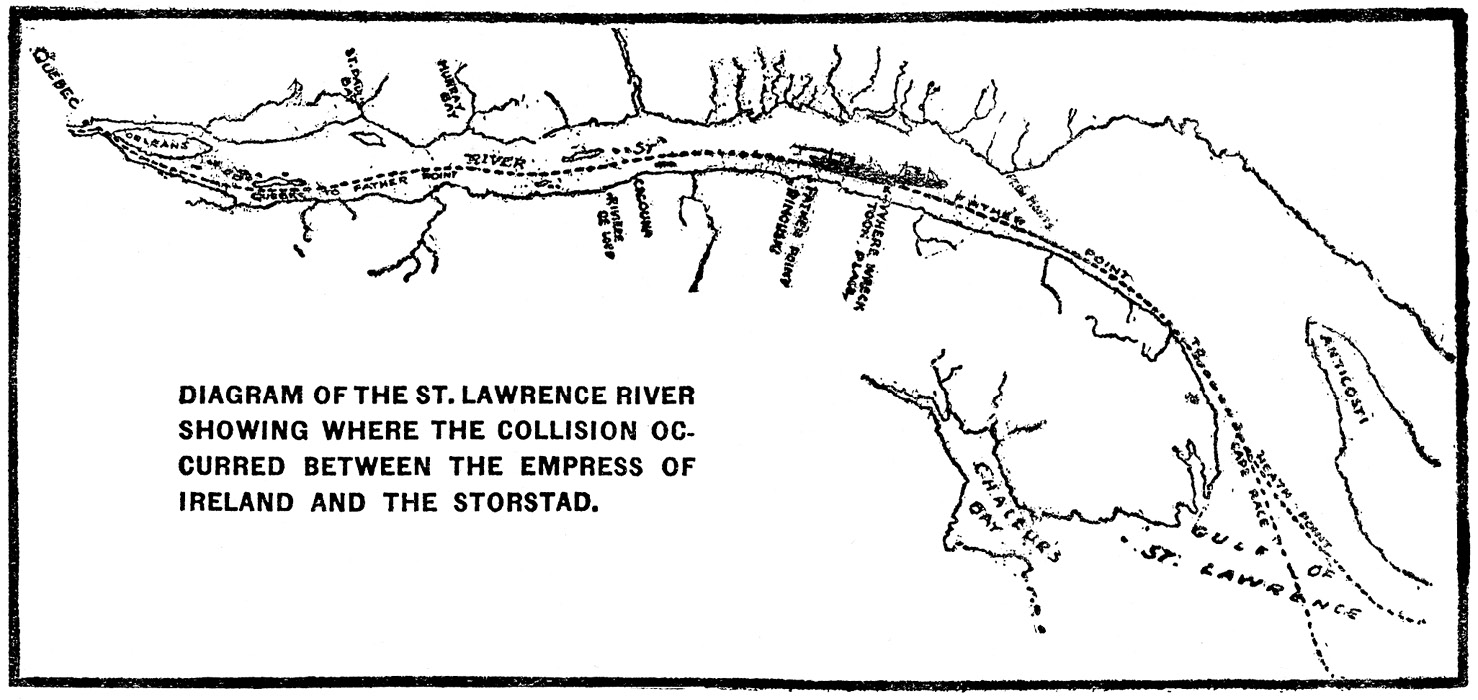

THE COLLISION ON THE ST. LAWRENCE

To make clear the somewhat contradictory testimony of Captain Kendall, of the Empress of Ireland, and Captain Andersen, of the collier Storstad, as to what took place just before and at the time of the fatal collision, diagrams Nos. 1 and 2, which are based on their statements, tell their own story. In No. 1 the vessels are shown in the position in which they were when first sighted, about which position both captains agree, the Storstad coming up the river on the starboard, or right side of the Empress of Ireland, so that those on the Storstad saw the green, or starboard, light of the Empress of Ireland over the port, or left, bow of the Storstad. The collier was in such a position that those on the Empress of Ireland could see both its red, port, light and its green, starboard, light. If the rules of the sea had been observed, the Empress of Ireland would have gone off to the right or steered to starboard so that the vessels would have passed each other easily. Instead, both vessels took a course which finally ended in position No. 2, in which the Storstad struck the Empress of Ireland between the funnels on the right, or starboard, side, hitting it a glancing blow with its starboard, or right, bow. As to how this fatal position was reached, the captains disagree, the question of the kind of signals and what response was made, or should have been made, being in dispute.

A Mortal Blow

In a moment the fate of the Empress was known to all. The one smashing blow had done for her and the great bull nose of the 3,500-ton freighter had crashed through the ribs and bulkheads. The one pithy sentence of Captain Kendall summed all. “The ship is gone,” he said. “Women to the boats.”

Kendall was hurt and in great pain, but he showed the pluck and decision of a naval officer. In the first minute of the disaster he ordered young Edward Bomford, the wireless operator, to flash the SOS call, the cry for help that every ship must heed. He ordered officers and stewards to collect as many passengers as could be found and hold them for the boats. He had nine lifeboats overboard within ten minutes.

Wireless Calls for Help

The SOS call was ticked out by Edward Bomford, the junior wireless operator. Bomford had just come on duty to relieve Ronald Ferguson, when the Storstad rammed the Empress. Both young men were thrown to the deck. As they picked themselves up they heard the chorus of the disaster, the cries, groans, and screams of injured and drowning passengers.

An officer came running to the wireless house with orders from Captain Kendall, but Bomford, at the key, didn’t have to wait for orders. He began to call the Marconi Station at Father Point, and kept at it desperately until he had the ear of the Father Point operator.

Then young Bomford turned his wireless to search the river and gulf, and he hurled the news of the Empress’s fate for 500 miles oceanward. Many steamships picked up the call, but they were hours away. They started for the position given, but long before they had made any progress the Empress and two-thirds of her ship’s company were under fifteen fathoms of water. Fourteen minutes is too brief a time for much rescue work.

Hundreds Drown in Cabins

Had there been time, hundreds who went down with the ship would have survived. A thousand men and women who had been asleep awoke too late to scramble to the decks. They were crushed or mangled by the bow of the Storstad, injured by splintered timbers, or overwhelmed in the terrific rush of water.

It is probable that scores who were asleep were killed instantly, but hundreds perished while feebly struggling for doorways, or while trying for a footing on sloping decks. The terror and confusion of the few minutes, while the Empress staggered, listed, and sank, can hardly be put in words. The survivors themselves could not describe those minutes adequately.

In the brief space of time between the shock of the collision and the sinking of the liner, there was little chance for systematic marshaling of the passengers. Indeed, everything indicates that hundreds of those on the steamer probably never reached the decks.

No Time to Rouse Passengers

The stewards did not have time to rouse the people from their berths. Those who heard the frenzied calls of the officers for the passengers to hurry on deck lost no time in obeying them, rushing up from their cabins in scanty attire. They piled into the boats, which were rapidly lowered, and were rowed away. Many who waited to dress were drowned.

The horror of the interval during which the Empress of Ireland was rapidly filling and the frightened throngs on board her were hurrying every effort to escape before she sank was added to by what seemed like an explosion, which quickly followed the ripping and tearing given the liner by the Storstad’s bow. As Captain Kendall afterward explained, this supposed explosion was in reality the pressure of air caused by the inrushing water. The ship’s heavy list as the water pouring in weighted her on the side she was struck, made the work of launching boats increasingly difficult from moment to moment, and when she finally took her plunge to the bottom, scores still left on her decks were carried down in the vortex, only a few being able to clear her sides and find support on pieces of wreckage.

In Their Nightclothes

Many passengers fortunate enough to get into the lifeboats found themselves garbed only in their nightclothes. No baggage was saved. The condition of the survivors was pitiable. Some had broken arms and legs, and all had suffered terribly. L. A. Gosselin, a prominent lawyer from Montreal, saved himself by clinging to a raft.

Picked Up the Captain

Ernest Hayes, an assistant purser, said that he leaped from the promenade deck a minute or two after the collision. He climbed into No. 3 lifeboat, which, a few minutes later, picked up Captain Kendall.

J. W. Black and his wife, who live in Ottawa, jumped together before the ship sank. They got on deck too late to find places in a lifeboat. They decided to jump and take their chances. Fortune was with them, for it sent wreckage to Mr. Black’s hand, and he kept his wife above water until a lifeboat reached them.

William Measures, of Montreal, a member of the Salvation Army band, jumped overboard and swam to a lifeboat. A young Englishman said there was a terrific shock when the Storstad struck. He had time only to throw a dressing gown over his pajamas and to awaken two of his friends.

To pluckily leap from the deck of the sinking liner and swim around for nearly an hour in the river, and then to fall dead from exhaustion on the deck of the Eureka, was the fate of an unknown woman.

Fourteen minutes settled the whole affair. With the decks careening, the captain, officers, and crew strove like fiends to release the boats. One after another, laden with a mass of humanity, sped away. The Storstad followed suit with as much ability, but the time was brief.

Boats there were aplenty, but time there was none.

When the listing increased and the nose of the ill-fated liner twisted skyward, panic seized upon the horde of persons, and once more a loud, prolonged burst of agony from several hundred throats vibrated through the fog.

Lifeboats Launched in Record Time

It takes five minutes to launch boats during a drill in harbor, when everything is calm and collected and the crews are all at their proper stations. The tarpaulin covering has to be removed, the falls cleared away and carefully tendered, and the boat fended off as it goes down the side.

But no more unfavorable conditions could be imagined than those prevailing when the order “stand by to abandon ship” rang out from the bridge. The ship was listing over at a terrifying rate. The seas were flooding her aft, and in addition to the list she was sinking stern first.

Men hurled from sleep by the shock of the collision had to hurry to their stations in the confusion that must have been inseparable from such an accident. Precious moments inevitably were lost in getting the boat crews to their post, and all the time the ship was going down. Once the crew members were at their stations, the launching of the boats must have gone on with the precision of clockwork. It was all done in twelve minutes. That was remarkable discipline. That these nine boats were lowered successfully in the few minutes remaining before the ship made her final plunge is something that will be remembered forever.

The Empress Goes Down

While these frantic attempts at rescue were going on, the doomed ship was rapidly settling. Her decks were awash, and then, with a spasmodic heave, as if giant hands from below were pulling her down, the massive sea castle tilted to the bottom. Wreckage, spars and bobbing heads, and the few small boats trying to escape the vortex—with the slow heaving bulk of the collier in the background—alone marked the scene of the catastrophe.

SIR THOMAS SHAUGHNESSY, PRESIDENT OF CANADIAN PACIFIC, DEPLORES LOSS OF LIFE

Sir Thomas Shaughnessy, president of the Canadian Pacific Railway, issued the following statement on the morning of the Empress accident:

“The catastrophe because of the great loss of life is the most serious in the history of the St. Lawrence route. Owing to the distance to the nearest telegraph or telephone station from the scene of the wreck there is unavoidable delay in obtaining official details, but we expect a report from Captain Kendall in the course of the afternoon.

“From the facts as we have them, it is apparent that about two o’clock this morning the Empress of Ireland when off Rimouski and stopped in a dense fog was rammed by the Norwegian collier Storstad in such a manner as to tear the ship from the middle to the screw, thus making the watertight bulkheads with which she was provided useless. The vessel settled down in fourteen minutes.

“The accident occurred at a time when the passengers were in bed and the interval before the steamship went down was not sufficient to enable the officers to rouse the passengers and get them into the boats, of which there were sufficient to accommodate a very much larger number of people than those on board, including passengers and crew. That such an accident should be possible in the river St. Lawrence to a vessel of the class of the Empress of Ireland and with every possible precaution taken by the owners to insure the safety of the passengers and the vessel is deplorable.

“The saddest feature of the disaster is, of course, the great loss of life, and the heartfelt sympathy of everybody connected with the company goes out to the relatives and friends of all those who met death on the ill-fated steamship.”