4

Miraculous Escape of the Few

HEROIC DEMEANOR OF CAPTAIN KENDALL—RESPONSE TO WIRELESS CALLS FOR HELP—EUREKA AND LADY EVELYN ON SCENE OF DISASTER—THE SEARCH FOR THE QUICK AND THE DEAD—TERRIBLE PLIGHT OF SURVIVORS—SAD SCENES AT RIMOUSKI—WILLING HANDS HELP—TWENTY-TWO DIE AFTER BEING RESCUED—TALES OF NARROW ESCAPES—THOSE WHO DIED BRAVELY

Amid the terrifying confusion, the awful darkness, and the harrowing scenes of death and despair, Captain Kendall bore himself like a true sailor as long as his ship stood under him. He retained such command of the situation that while the Storstad’s stem still hung in the gap it had made in the Empress’s side, Captain Kendall begged the master of the collier to keep his propellers going so that the hole might remain plugged.

Captain Kendall stood on his bridge as the ship went down. One of the boats from the liner picked him up, and he directed its work of saving others until the craft was loaded. The captain was injured in the crash and suffered from exposure.

Response to Wireless Calls for Help

Brief as was the time in which the SOS calls could be sent out from the wireless on the stricken Empress, they were caught by Crawford S. Leslie, the assistant wireless operator at Father Point. Leslie roused Whitehead, the chief operator, and John McWilliams, the manager of the telegraph company. Whitehead at once took charge of the wire, while McWilliams and Leslie notified the government boats Eureka and Lady Evelyn. The Eureka had steam up, having taken the mails to the Empress shortly before, and got under way at once, followed quickly by the Lady Evelyn.

Eureka and Lady Evelyn on the Scene of Disaster

The Eureka and Lady Evelyn found, on reaching the point where the Empress sank, a scene not dissimilar to that which greeted the liners which rushed to the Titanic’s aid. They found the ship sunk, and the surface of the water, fortunately calm, dotted with lifeboats and smeared with floating debris from which many poor souls had been forced by exhaustion to loosen their hold.

In the lifeboats were huddled the survivors, dazed and moaning, some then dying of injuries sustained in the crash or in the rush of leaving the sinking Empress. Crushed by the collision, injured in their efforts to leap into lifeboats, or suffering from immersion in the icy water and exposure in the lifeboats in which they escaped, the survivors presented a pitiable condition.

The Search for the Quick and the Dead

The government steamships worked rapidly and took on the survivors from the lifeboats and a few persons that were clinging to bits of wreckage. Fifty dead bodies were picked up and the women cried aloud as they were brought aboard, some eagerly scanning the faces of the corpses for lost relatives and friends. Several of them walked around wringing their hands in a wild hysteria, and even the hardened members wept at the terribly pathetic scene.

One woman, whose identity was not established, let go her hold on a broken timber and tried to swim to the Lady Evelyn. She was nearly naked and too far gone from exposure to reach the steamship.

The Eureka picked up thirty-two of the survivors who were injured, and recovered a number of dead bodies. The Lady Evelyn rescued the great majority of the survivors. She also saved Captain Kendall.

The government boats, Lady Grey and Strathcona, on arriving later, found the Eureka and Lady Evelyn lying to in proximity to the Storstad, picking up scattered boats and searching among the scraps of floating debris.

Terrible Plight of Survivors

Many of the survivors were in a terrible condition following the exposure; the heartrending shock had driven some of them to the verge of hysterical insanity. Others, with the echo of the death screams ringing in their ears, were gathered in a dazed and pathetic condition. The fact that they were saved did not seem to be appreciated. The vision of death stayed with them for hours, and in many instances utter nervous collapse followed.

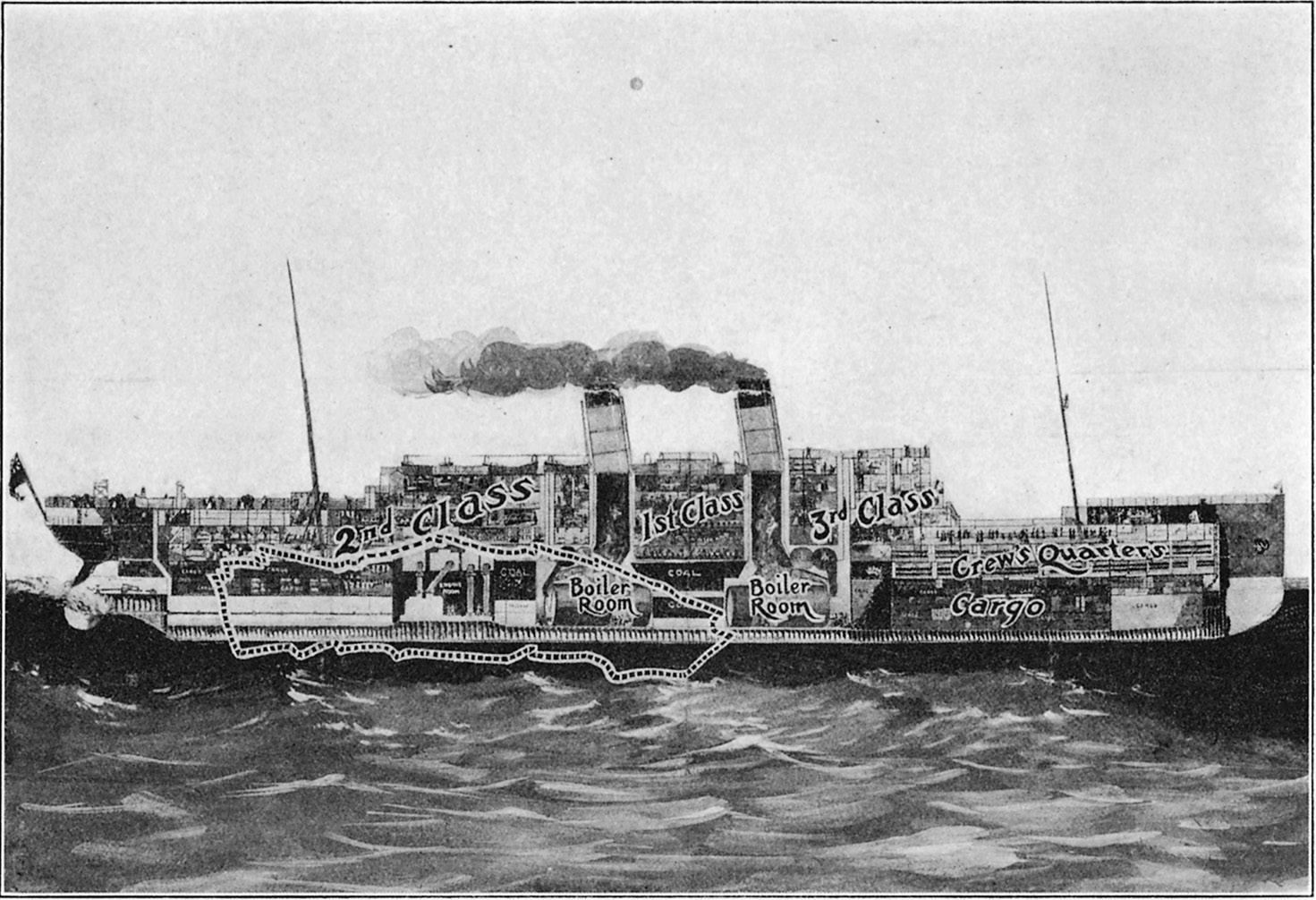

Courtesy of the Philadelphia Press

SECTIONAL VIEW OF THE EMPRESS OF IRELAND

Early impressions of the injury to the Empress of Ireland were that a large portion of the starboard side of the liner was torn open, as shown by the dotted line in the illustration. The testimony before the Royal Commission of Inquiry, however, gives no basis for this hypothesis, going to show only that the Storstad cut a great gash in the Empress on the starboard side near the forward funnel.

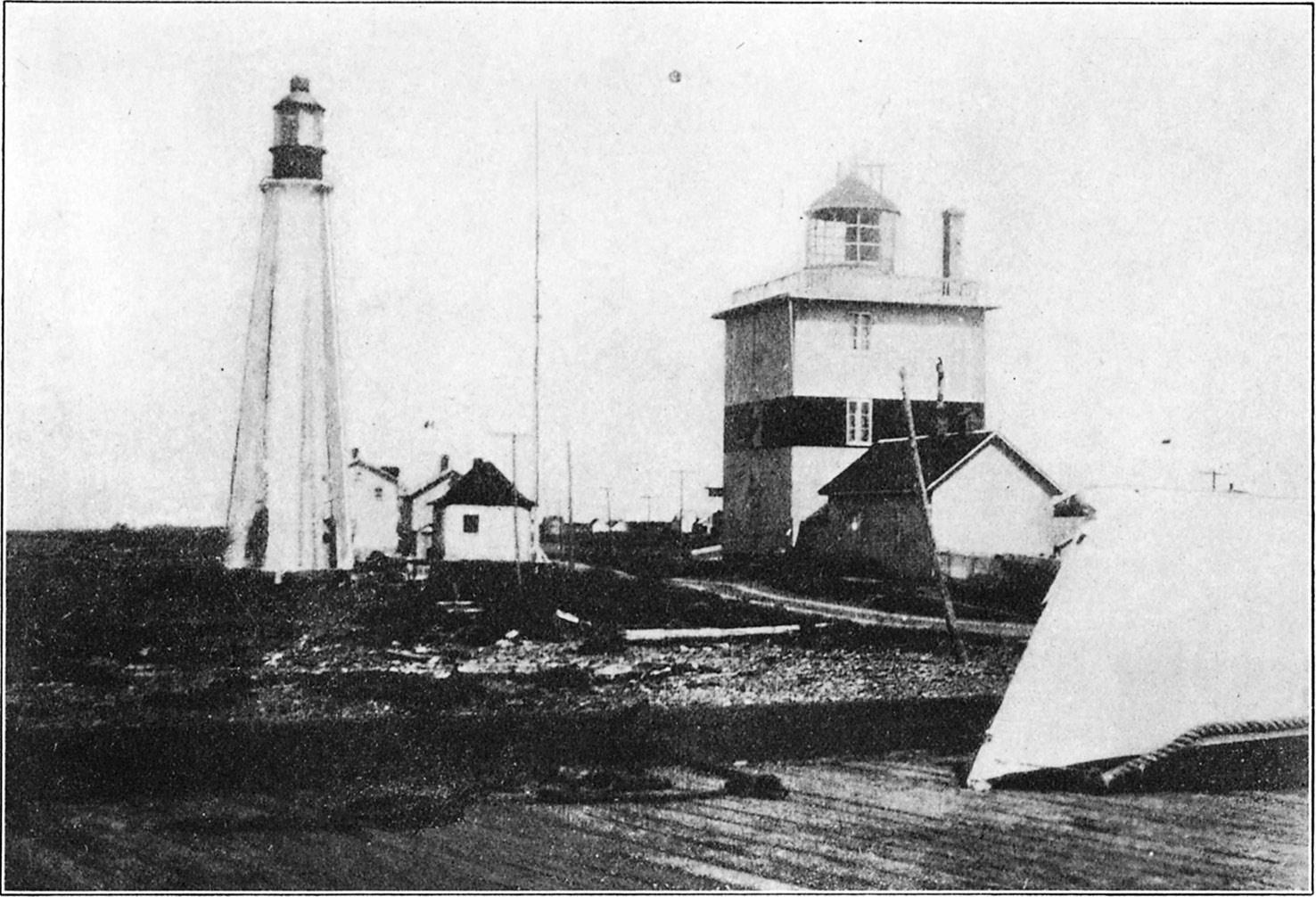

Photo by Bain News Service

THE WIRELESS STATION AT FATHER POINT

The first report of the disaster came to this station from the sinking ship. “S. O. S.,” came through the night again and again, and then suddenly ceased. All was over, but the station saved many lives by calling ships to the rescue.

The Eureka and the Lady Evelyn cruised at the scene of the disaster for half an hour, until their commanders were certain that there were no more survivors to be picked up.

Sad Scenes at Rimouski

When the tug Eureka, with thirty-nine survivors, came up to the Father Point wharf, an agent of the Canadian Pacific Railway advised Captain Boulanger, of the tug, to put in at the Rimouski wharf for the reason that better care could be given to the survivors there. Rimouski is a town of 2,000, with doctors and medical facilities.

The Canadian Pacific official telephoned to Rimouski ahead of the Eureka and ordered all the cabs and doctors that could be obtained. Within an hour the Eureka’s rescued were being cared for at Rimouski. There were distressing, unforgettable scenes as the living and dead were delivered to the shore.

The Lady Evelyn, with survivors and corpses, arrived at the Rimouski wharf later. Among the rescued were men and women who had not had time to bring with them more than their nightclothes. The officers and crew of the mail tender had done what they could in providing coats, but their supply was not ample for the hundreds, and many suffered terribly from the cold.

The mercury was down to a few degrees above freezing and these wretched ones had endured exposure for more than two hours.

Willing Hands Help

At 6:10 A.M. the Norwegian collier Storstad, coal-laden from Sydney, Nova Scotia, for Montreal, came along slowly. When her bow was seen smashed in it became known that she was the vessel that had struck the Empress of Ireland the fatal blow. The Storstad was not too much damaged to allow her to proceed on to Quebec under her own steam. She also had some survivors and dead bodies, which were taken from her by the steamers Eureka and Lady Evelyn and landed on the Rimouski wharf.

Most of the population of Rimouski were at the wharf, ready and eager to do what was possible. They carried blankets, clothing, hot coffee, food, and medicines. The mayor, H. R. Fiset, was in charge of the relief work, acting with the local Canadian Pacific agents.

McWilliams, the wireless man from Father Point, had hurried over to assist in the relief work, and few gained more praise than was accorded to him. Every doctor in the town was hard at work for hours, going from house to house where the survivors were quartered.

Twenty-two Die After Being Rescued

Two relief stations were established, one at the wharf and one at the Intercolonial Railroad station, but these were not adequate for the care of so many. The grave problem was solved by the openheartedness of the townspeople, who turned over their own homes to the suffering. Of the survivors, it was found that forty-seven were from the second cabin. In this class had traveled about 150 Salvation Army delegates, who were on their way from the Dominion cities to attend a great international conference in London. Only a few of these were rescued.

Twenty-two persons died of their injuries or from exposure after being taken out of the lifeboats or from floating wreckage. One man suffered from broken legs. A woman was found who had a leg and arm broken. Others were crushed or injured internally. Many of the survivors were rushed to Quebec after they had had preliminary care at Rimouski.

Tales of Narrow Escapes

Some of the survivors were able to give snatches of their experience. One explained quietly that he had made up his mind that he had to die. The boats had gone. He could find nothing that promised to support him in the water. He made his way to the rail of the ship and waited until it sank.

As he went down he held his breath, held it for an age, it seemed to him, but finally he came to the surface and luckily near a lifeboat. A sailor seized him by the collar and hauled him in.

Those Who Died Bravely

The penetrating, lasting grief is that the fortunates who escaped were but few of the 1,475 souls that set sail on the Empress. Death’s threatening wave engulfed almost all of them, but we may be sure that whether in the isolation of their cabins or in the crowded confusion of the final plunge on deck, they died bravely. That, indeed, seems to be the outstanding feature of this terrible tale of the sea. To face death unafraid, whether it comes in the sickroom, in tempest, fire, or flood, is the supreme test of fortitude. In our sorrow for those who died and for those who were bereaved let us remember that a thousand Canadians went to their deaths—as Britons for centuries have gone—masters of themselves, with head erect and spirit unconquered by the king of terrors.