16

Placing the Blame

THE ROYAL COMMISSION OF INQUIRY—IMPORTANT DISCREPANCIES IN THE TESTIMONY—DISAGREEMENT AS TO SPEED—CONTRADICTIONS AS TO WHY THE STORSTAD BACKED—THE CAPTAINS DIFFER—A SENSATIONAL CHARGE—QUARTERMASTER GALWAY’S TESTIMONY—WHERE THE EMPRESS WAS STRUCK—STORSTAD PORTED HER HELM—A HUMOROUS INCIDENT—THE DIVERS TESTIFY—BOATSWAIN’S SENSATIONAL EVIDENCE—TESTIMONY OF EXPERTS—ADDRESSES OF COUNSEL—COMMISSION HOLDS STORSTAD RESPONSIBLE—RECOMMENDATIONS

The shock dealt to the civilized world by the news that a catastrophe in the St. Lawrence River had cost a thousand human lives was scarcely greater than the ensuing demand for a thorough investigation of all of the facts connected with the disaster.

The Royal Commission of Inquiry

The minister of Marine and Fisheries, the Honorable J. D. Hazen, acted promptly in appointing a Royal Commission of Inquiry, consisting of Lord Mersey (chairman), who had conducted the British inquiry into the Titanic disaster; Sir Adolphe Routhier, president of the Court of Admiralty for the Province of Quebec; and the Honorable Ezekiel McLeod, judge of the Supreme Court and of the Vice Admiralty of New Brunswick.

The commission assembled on June 16, at Quebec, where it had the assistance, as assessors, of Commander Caborne, of the Royal Naval Reserve; Professor John Welsh, of Newcastle, England; Captain Demers, Dominion wreck commissioner; and Engineer-Commander Howe, of the Canadian Naval Service. Heading an illustrious array of counsel were E. L. Newcombe, K.C., deputy minister of justice, representing the government; Butler Aspinall, K.C., of London, representing the Canadian Pacific Railway Company; and C. S. Haight, K.C., of New York, representing the master and owners of the Storstad.

Important Discrepancies in the Testimony

The first two witnesses called were Henry George Kendall, master of the Empress of Ireland, and Alfred Tuftenes, chief officer of the Storstad.

The chief discrepancies in the stories of these opposing witnesses occurred in that portion devoted to the course of events which took place after the heavy fog rolled up from the shore and formed a barrier between the vessels. Captain Kendall stated decisively that there never was one blast alone sounded from the bridge of the Empress. Chief Officer Tuftenes declared with equal certainty that the first signal which came across the rolling bank of fog was one long blast, which he interpreted as meaning that the Empress was continuing on her way. He replied with a similar signal.

Both officers maintained that, had the vessels held to their courses set when they first sighted each other’s lights, there would have been no collision. But Captain Kendall’s asseveration was that he signaled three blasts, meaning that he ordered the ship full speed astern. This was the first discrepancy.

Disagreement as to Speed

The second discrepancy of outstanding importance was in regard to the speed at which the vessels were traveling when they came in sight of each other through the fog, one hundred feet apart.

Captain Kendall stated that as soon as he saw the collier he realized that a collision was inevitable, and he telegraphed “full speed ahead,” but his ship had no way on her and the collision came. He stated that by the curling waters at the bow of the Storstad he was certain that she was traveling some ten knots an hour.

Chief Officer Tuftenes stated that he had stopped his ship and then, because she refused to answer to her helm, he had given the command “slow ahead,” in order to prevent her shearing with the current. This was about a half a minute before the Empress was sighted one or two ship lengths away. When the liner was sighted, the engines were ordered “full steam astern,” and this was the condition, according to this witness, instead of the ten knots an hour speed which was Captain Kendall’s estimate.

Chief Officer Tuftenes also declared that when he sighted the Empress, she was moving ahead at a fast rate of speed, and it was this fact that made it impossible for the Storstad to hold her stem in the wound her anchors gashed in the starboard side of the liner.

Contradictions as to Why the Storstad Backed

The reason for the Storstad’s movement after she struck the Empress of Ireland was the third divergence of opinion. The evidence showed that both Captain Kendall and Captain Andersen realized the necessity of keeping the stem of the collier in the wound in the liner’s side. The divergence of opinion was about the reason why the desired position of the two vessels was not maintained.

Captain Kendall’s explanation of the backing up of the Storstad was that she rebounded after the terrific blow, her engines were full speed astern, and she swung about because she lost her heading when her engines were reversed. This brought the two vessels side by side, and from this position, he claimed, the collier continued to draw away until a mile separated the two ships.

But Chief Officer Tuftenes stated that Captain Andersen gave the order “full speed ahead,” as instructed by Captain Kendall, to keep her bow in the wound, and that it was because the Empress was moving ahead that the collier’s stern was forced around in a half circle, still with her stem in the gigantic gash, and then, by the force of the water against her side, her bow was pulled out, and the vessels stood heading more or less in the same direction. Both officers agreed that the collier collided with the liner at something less than a right angle.

The Captains Differ

With the examination of Captain Andersen it became known what mistakes of judgment and navigation the masters of the Empress and the Storstad each thought the other made.

Captain Kendall, of the Empress, gave his opinion on varying points on the opening day of the proceedings. During the second day’s session Captain Andersen, of the collier, named the three blunders which, in his idea, were made on board the Empress.

Briefly, Captain Kendall claimed that the Storstad seemed to have changed her course in a heavy fog, with another vessel in the vicinity, which, it is said, is against all the ethics of seamanship. He gave as his opinion that this was done probably to avoid Cock Point shoal. His charge, not made directly, was that the Storstad ran through the fog at ten knots an hour, which was said to be another infraction of the rules. These were the two chief points which, Captain Kendall submitted, were the most probable cause of the collision.

Captain Andersen, on the other hand, stated that three blunders, in his opinion, were made on board the Empress. The first was that, having ported her helm and brought the ships red to red, which means that the starboard light alone of each ship was visible to the other, the Empress starboarded, changing her course toward the south shore, “a very risky thing to do.”

The second blunder, he believed, was that when two long blasts were sounded, meaning that the Empress was stopped, she was still under way, “a remarkable blunder,” and the last blunder, in his opinion, was that some five or six minutes after blowing the three blasts, when she came in sight she was going eight or ten knots an hour, “an extraordinary blunder.”

A Sensational Charge

The most sensational incident of the investigation into the circumstances attending the sinking of the Empress of Ireland occurred on Thursday, the eighteenth, when serious statements were made by Mr. Haight, counsel for the Storstad, to the effect that he had been informed by a quartermaster of the Empress of Ireland that for five minutes, while she was on her way down the St. Lawrence after leaving Quebec, the steering gear of the Empress of Ireland was out of order, and that during this period she nearly ran down another vessel. The quartermaster’s name was James Galway.

Quartermaster Galway’s Testimony

On the following day Galway was put on the witness stand. He was evidently unnerved by the quick fire of questions which assailed him after every answer he gave. As he paused to give his answer, first repeating the question like an echo, he glanced round the room at the gathering of shipping experts, started a reply, and in his nervousness, stopped again.

As he made some little slips, a titter ran round the room and the witness was more unnerved than ever.

He stated that on one occasion when the Empress of Ireland was in the Lower Traverse, below Quebec, she behaved in an extraordinary manner, swaying from side to side.

“Am I to understand,” asked Lord Mersey, “that she turned to port or starboard at her own sweet will?”

“Yes, that is right,” Galway replied.

Galway further declared that when he put the helm to starboard the head of the vessel went to port and then came back again.

“She changed her mind,” jocularly commented Lord Mersey.

On the night of May 28, Galway added, between ten and twelve, he put the steering gear to port and it jammed for a few minutes.

George Sampson, chief engineer of the Empress, whose duty it was to examine the steering gear, testified in rebuttal to Galway. He was emphatic in his assertion that the steering gear was in proper condition on the day of the collision.

From the steamship Alden, however, there were witnesses who contended that the course of the Empress was somewhat erratic. The Alden was the third vessel which figured in the charges made by counsel for the Storstad. While she was on her way down the river, it was alleged, the Empress had answered her helm so badly that she had almost run down the Alden.

Where the Empress Was Struck

An interesting exhibit shown during the proceedings of the inquiry was a model of the bow of the Storstad, showing her twisted stem; another was that of a cabin plate from the Empress, found on the Storstad after the collision. The number was 382, and was that of a cabin on the saloon starboard deck, near the forward funnel.

The latter exhibit was particularly interesting as giving an indication of the point where the Empress was struck, and how far the stem of the Storstad plowed through her side.

When the officers and men from the Storstad continued their testimony before the Royal Commission of Inquiry on Saturday, the twentieth, some remarkable declarations were made.

Storstad Ported Her Helm

It was Jakob Saxe, the third officer of the collier, who provided the sensation of the session. He told how he was standing on the bridge of the Storstad, just before the collision, when the navigating officer gave the order to port the helm a little.

“But,” Lord Mersey asked in surprise, “when he gave the order to change the course in a fog, did you think about it, remembering that you must not change course in a fog?”

Yes, the witness admitted, I thought about it. But, Saxe continued, he did not think it was dangerous.

Saxe then created a buzz of excitement in the courtroom by relating how, without any orders, he had put the wheel over hard aport.

“That,” Lord Mersey continued, “to me is news.”

Again and again the witness was pressed by counsel as to the effect of his putting the wheel of the Storstad hard aport, whether it might not have been responsible for the collision, but he strenuously denied this.

The evidence given on Monday, the twenty-second, threw little additional light on the disaster or its cause.

The second officer of the Storstad persisted that the Empress was moving rapidly. He had rushed on deck immediately after the collision, he said, and the Empress was moving forward. He could not remember whether the bow of the Storstad was held fast in the side of the Empress.

“But,” Lord Mersey asked, “whether they were fast together or not, the Empress was moving forward. Is that right?”

“Yes,” the witness insisted.

One witness heard during Monday’s session gave a peculiar reason for the closing of portholes on a steamer.

A Humorous Incident

When there was a fog, he informed Lord Mersey, he would go and close the cabin portholes.

“But,” said Lord Mersey, “that is for the comfort of the passengers, not for the safety of the ship?”

“There is no other reason that I can think of,” was the reply, “except that it is a matter of form.”

The little touch of red tape amused the court and sent a roar of laughter around the room.

“And,” Lord Mersey drily added, “suppose you go into a cabin on a foggy night and you begin to close a porthole when a passenger wants it open, what do you do?”

“Oh, I close it,” the witness replied, and again there were roars of laughter.

The Divers Testify

G. W. Weatherspoon, of the American Salvage Company, which conducted diving operations on the scene of the wreck, was closely examined on Tuesday, the twenty-third, in an effort to learn which of the two ships had changed her course. Counsel for the Storstad contended that the position of the Empress as she lay on the bed of the river was proof of his contention.

Weatherspoon was closely pressed by Mr. Aspinall on the question of the importance of the currents as the point where the Empress lay.

“There was always a current there,” Weatherspoon said.

“And, therefore,” Mr. Aspinall queried, “the heading of the vessel may have been affected?”

“Very possibly,” the witness admitted.

Mr. Haight suggested that the influence of the currents might be scientifically determined by government surveyors placing down buoys.

“I must leave the government to make up its mind on that,” Lord Mersey replied.

Weatherspoon spoke of the danger of his undertaking. Divers had attempted to ascertain the damage of the ship, but the hazard was very great. In his opinion it would be impossible to raise the vessel.

On the following day Winfrid Whitehead, one of the Essex divers, one of the men who cautiously made his way along the hull, related his experiences to the court. He told his story simply. He had gone down to find out in which direction the ship was lying. He descended onto the side of the vessel, felt at her plates, to determine the direction of her stem, and then walked forward. By this means the air bubbles rising from him told the officer above which way the vessel was lying.

This direction, Chief Gunner Macdonald informed the court, was northeast and southwest, the stem of the ship being northeast.

Boatswain’s Evidence Sensational

Something of a sensation was caused shortly after the opening of Wednesday’s session by the evidence of Alexander Redley, the boatswain’s mate of the Empress. During a preliminary examination, it appears, Redley stated that he heard one long blast blown by the whistle of his ship ten minutes before the collision.

That such a signal was blown, a signal signifying “I am going ahead,” was denied by Captain Kendall, when he was on the stand.

“Can you tell me,” Lord Mersey asked counsel for the Dominion government, “why it is this evidence was not called sooner? It seems to me as if it were put in at the last moment. It is important whether such a blast was blown or not.”

In reply to a direct question from Lord Mersey, Redley could not say definitely if or when he had heard the Empress blow one long blast.

Testimony of Experts

The afternoon’s evidence was a maze of technicalities. The design of the steamer, the possible effect of such and such a blow, assuming the speed to be such and such, the effect of the collision on the heading of the Empress—all this was the trend of the questions asked of Mr. Percy Hillhouse, a naval architect employed by the Fairfield Ship-building Company, the builders of the Empress.

From the maze one learned that a foot had been added to the rudder of the Empress of Ireland in 1906.

“On the trials,” said Mr. Hillhouse, “everybody was absolutely satisfied with her steering qualities. But sometime later the forepart of the rudder got carried away accidentally, and when that was being renewed advantage was taken of the change to slightly increase the area of the rudder.”

A few calculations submitted by Mr. Hillhouse gave a graphic idea of the great gap in the side of the liner. He estimated, he said, that the area of the breach was 350 square feet, and that 265 tons of water per second poured through the hole. At this rate the boiler space would be filled in from one and a half to two minutes.

On the following day, John Reid, the naval architect, called by the owners of the Storstad, entered the box equipped with photographs and a model of the Storstad’s bow, made to scale. The most interesting assertion of Reid was that the rudder of the Empress was quite small.

“Do you know,” Mr. Aspinall asked, “how the area of the rudder of the Empress compared with the area of the rudder of other ships?”

Mr. Reid replied, “It was considerably smaller, but there is no type of vessel with which you could accurately compare it, the Empress having the peculiar formation of fullness about the stern.”

On this point, Percy Hillhouse, of the Fairfield Shipbuilding Company, the builders of the Empress, was recalled. He thought that Mr. Reid’s criticism was not just. The area of the Empress in proportion to the size of the ship rudder compared very favorably with that of other large vessels. A mean percentage he had taken of thirteen large vessels gave an average of 1.265. For the Empress of Ireland, the figure was 1.53 percent.

Address of Counsel

After all of the testimony was in, George Gibson, counsel for the Seamen’s and Firemen’s Union of Great Britain and Ireland, made the first address of counsel. His speech was brief, Mr. Gibson making the recommendation that (1) the number of able seamen on passenger ships should be increased to two for each boat; (2) boat drill should consist of the lowering of every boat into the water; and (3) rafts or floats should be provided so that firemen and stokers, who would be the last to leave a ship, would have a better chance to escape.

Mr. Aspinall, in summing up, drew attention to the evidence of the Storstad’s officers which tended to corroborate the claims of the captain and owners of the Empress. “We were contending,” he said, “that what caused the collision was a porting and a hard porting of the helm on the part of the other vessel. It is remarkable that as this case has been developed and the evidence has been sifted, it should be established that the helm of the Storstad was ported and hard ported, and without any orders to that effect having been given by her navigating officer. That is the whole feature of this case, and I submit it is of immense value in determining where the truth of this story lies.”

Mr. Haight defined the accident as absolutely inexcusable. The whole world wanted to know who was responsible; and Mr. Haight unhesitatingly fixed the blame on the ship which, while running through a fog, changed her course. That ship, he argued, was the Empress of Ireland.

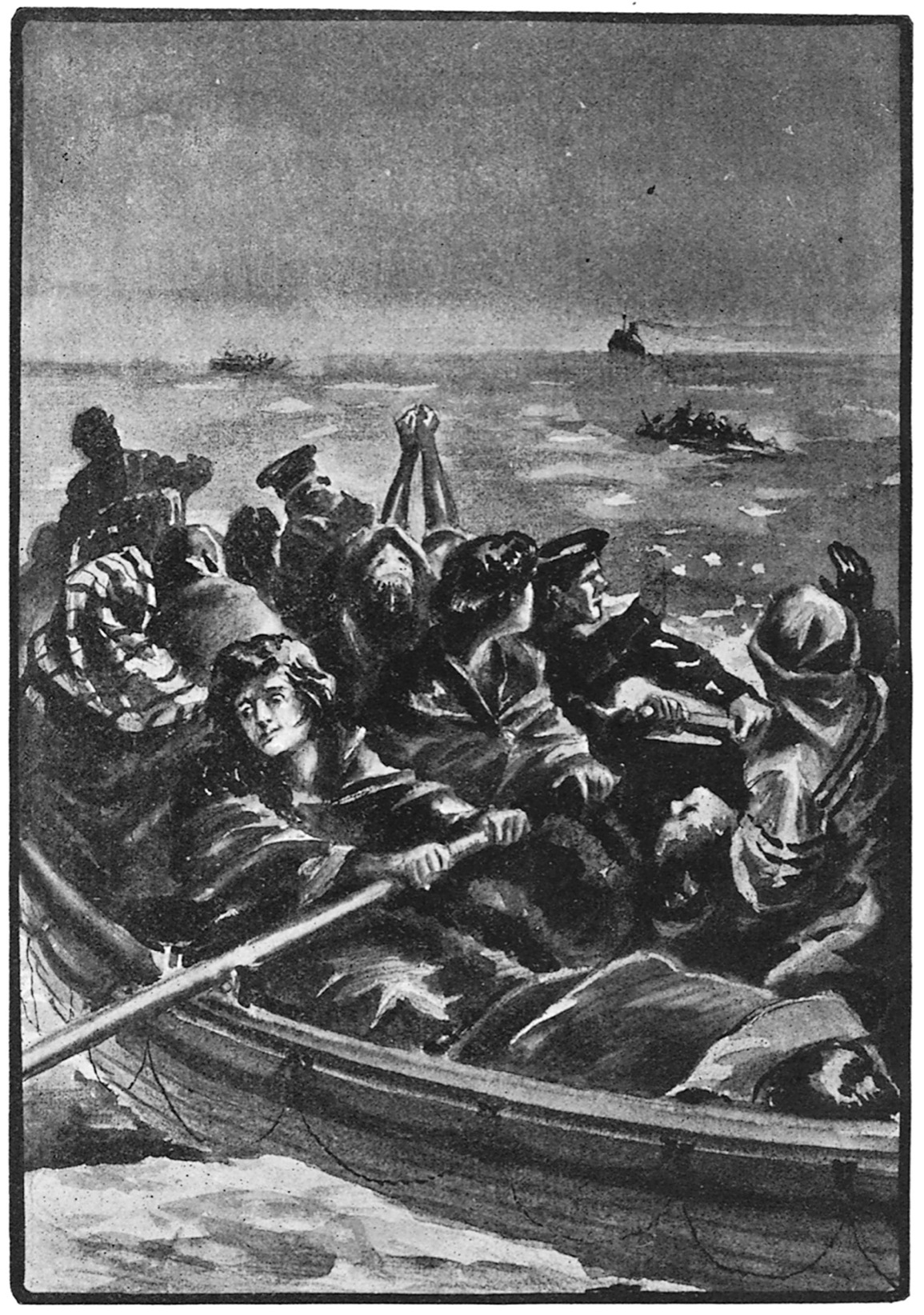

IN THE DRIFTING LIFEBOATS

Here the intense physical suffering from cold and exposure, added to the mental agony preceding and accompanying it, overwhelmed many of the boats’ occupants. In consequence, the Carpathia, which rescued the survivors, was literally a floating hospital during her sad journey back to New York.

COMMISSIONER DAVID M. REES

Of Toronto, who was in command of the Toronto detachment of the Salvation Army on the Empress of Ireland, and was among those lost in the disaster.

He could only think of three reasons. If the Empress had dropped her rudder entirely, she might have steered. There was no charge that the Storstad did not steer. Mr. Aspinall had fully recognized her steering qualities, and had indeed made them the basis of his arguments. The Empress might not have steered well. They had direct evidence that in some respects the Empress was an innovation. He could never believe that Captain Kendall deliberately turned his splendid ship straight across the bows of the Storstad.

There was a new note in the closing address of E. L. Newcombe, deputy minister of justice, who represented the Dominion government. Mr. Newcombe argued that both vessels might have been at fault—the Empress for lying dead in the water while entering fog and knowing another vessel to be in dangerous proximity—the Storstad for the hard-porting of her helm by her third officer, without instructions by her navigating officer.

Commission Holds Storstad Responsible

The report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry was filed on July 11, the decision of the commission being as follows:

First. The Storstad is responsible for the accident, because she changed her course. The helm of the Storstad was ported by order of Chief Officer Alfred Tuftenes, who thought the Empress was at port, whereas, in reality, she was on the starboard.

Second. The first officer is also blamed for having failed to call the captain, Thomas Andersen, when the fog came on. There is nothing to blame in the course followed by the two ships before the fog came on.

Third. It is virtually certain that some of the bulkheads of the Empress were not closed at the time of the collision.

Discussing the disaster, the report said:

It is not to be supposed that this disaster was in any way attributable to any special characteristics of the St. Lawrence waterway. It was a disaster which might have occurred in the Thames, in the Clyde, in the Mersey or elsewhere in similar circumstances.

There is, in our opinion, no ground for saying that the course of the Empress of Ireland was ever changed in the sense that the wheel was willfully moved; but as the hearing proceeded another explanation was propounded, namely, that the vessel changed her course, not by reason of any willful alterations of her wheel, but in consequence of some uncontrollable movement, which was accounted for at one time on the hypothesis that the steering gear was out of order, and at another by the theory that, having regard to the fullness of the stern of the Empress of Ireland, the area of the rudder was insufficient. Evidence was called in support of this explanation.

The principal witness on the point as to the steering gear was a man named Galway, one of the quartermasters on the Empress of Ireland. He said that he reported the jamming incident to Williams, the second officer on the bridge (who was drowned), and Pilot Bernier. He said he also mentioned the matter to Quartermaster Murphy, who relieved him at midnight of the disaster. Pilot Bernier and Murphy were called, and they denied that Galway had made any complaint whatever to them about the steering gear.

Galway gave his evidence badly, and made so unsatisfactory a witness that we cannot rely on his testimony.

On the whole question of the steering gear and rudder we are of the opinion that the allegations as to their conditions are not well founded.

Recommendations

The commission’s report contained the following recommendations:

1. That a maritime rule be adopted compelling ships to close their bulkheads when fog comes on and also at night, whether the weather is foggy or not.

2. That different stations be established for the ships to take on and leave off pilots so that they would not be obliged to meet one another.

3. That more life rafts be put among the lifesaving equipment on ships so that if a boat sinks before the lifeboats can be lowered, the rafts will slip off and float in the water.