Chapter 3. The process framework and the project manager’s role: It all fits together

All of the work you do on a project is made up of processes. Once you know how all the processes in your project fit together, it’s easy to remember everything you need to know for the PMP exam. There’s a pattern to all of the work that gets done on your project. First you plan it, and then you get to work. While you are doing the work, you are always comparing your project to your original plan. When things start to get off-plan, it’s your job to make corrections and put everything back on track. And the process framework—the process groups and knowledge areas—is the key to all of this happening smoothly.

If your project’s really big, you can manage it in phases

A lot of project managers manage projects that are big or complex, or simply need to be done in stages because of external constraints, and that’s when it’s useful to approach your project in phases. Each phase of the project goes through all five process groups, all the way from Initiating to Closing. The end of a phase is typically a natural point where you want to assess the work that’s been done so that you can hand it off to the next phase. When your project has phases that happen one after another and don’t overlap, that’s called a sequential relationship between the phases.

When your project has sequential phases, each phase starts after the previous phase is 100% complete.

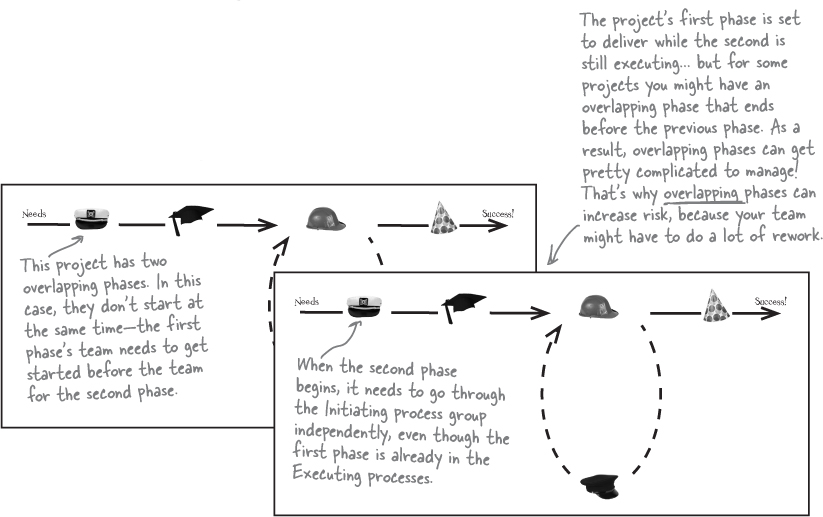

Phases can also overlap

Sometimes you need teams to work independently on different parts of the project, so that one team delivers their results while another team is still working. That’s when you’ll make sure that your phases have an overlapping relationship. But even though the phases overlap, and may not even start at the same time, they still need to go through all five process groups.

Iteration means executing one phase while planning the next

There’s a third approach to phased projects that’s partway between sequential and overlapping. When your phases have an iterative relationship, it means that you’ve got a single team that’s performing the Initiating and Planning processes for one phase of the project while also doing the Executing processes for the previous phase. That way, when the processes in the Executing and Closing process groups are finished, the team can jump straight into the next phase’s Executing processes.

Note

This is a really good way to deal with an environment that’s very uncertain, or where there’s a lot of rapid change. Does this sound like any of the projects you’ve worked on?

Iteration is a really effective way to run certain kinds of software projects. Agile software development is an approach to managing and running software projects that’s based on the idea of iterative phases.

Break it down

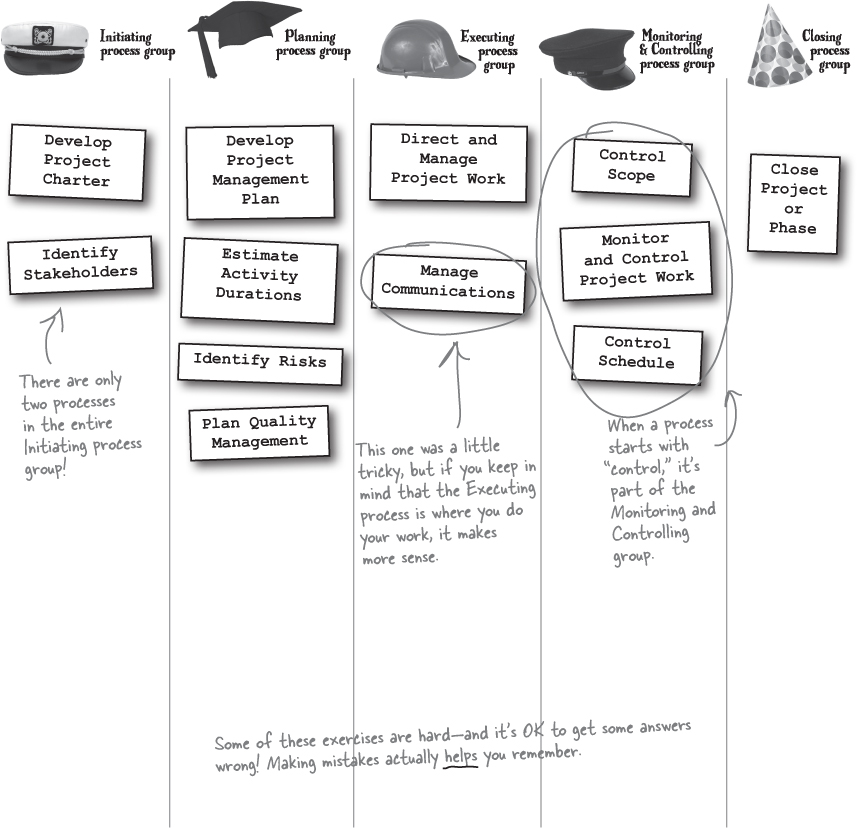

Within each process group are several individual processes, which is how you actually do the work on your project. The PMBOK® Guide breaks every project down into 49 processes—that sounds like a lot to know, but don’t start looking for the panic button! In your day-to-day working life, you actually use most of them already…and by the time you’ve worked your way through this book, you’ll know all of them.

Process Magnets

Below are several of the 49 processes. Try to guess which process group each process belongs to just from the name!

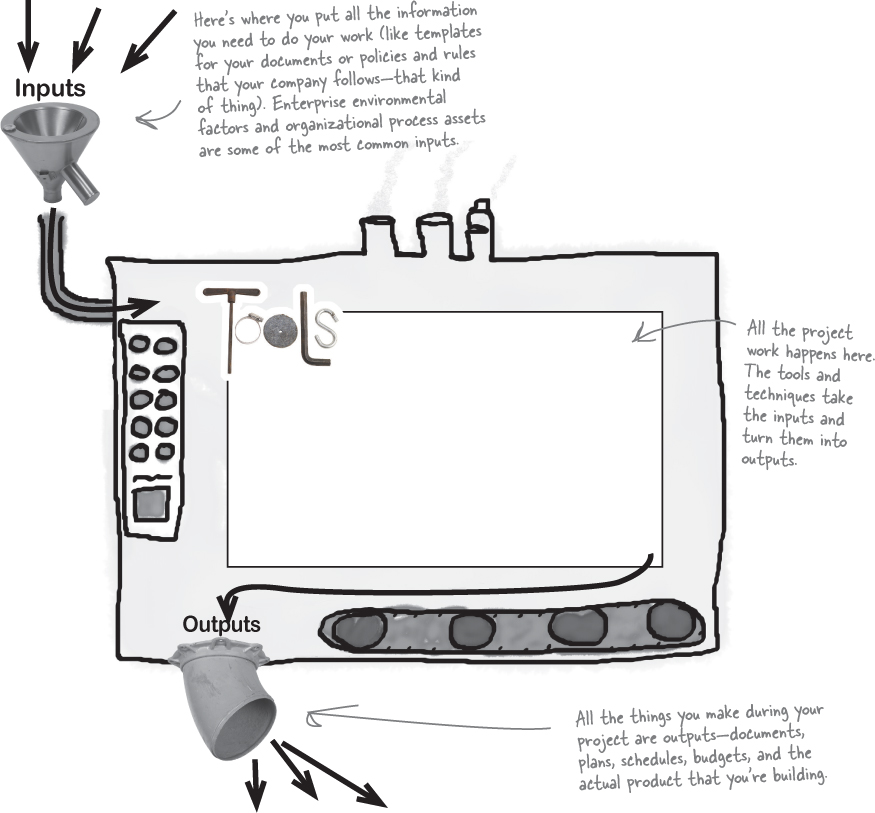

Anatomy of a process

You can think of each process as a little machine. It takes the inputs—information you use in your project—and turns them into outputs: documents, deliverables, and decisions. The outputs help your project come in on time, within budget, and with high quality. Every single process has inputs, tools and techniques that are used to do the work, and outputs.

These processes are meant to work on any type of project.

The processes are there to help you organize how you do things. But they have to work on small, medium, and large projects. Sometimes that means a lot of processes—but it also ensures that what you’re learning here will work on all your projects.

Note

Keep your eyes out for discussion of “tailoring” later in the book, where we’ll go into more detail about this topic.

there are no Dumb Questions

Q: Can a process be part of more than one process group?

A: No, each process belongs to only one process group. The best way to figure out which group a process belongs to is to remember what that process does. If the process is about defining high-level goals of the project, it’s in Initiating. If it’s about planning the work, it’s in Planning. If you are actually doing the work, it’s in Executing. If you’re tracking the work and finding problems, it’s in Monitoring and Controlling. And if you’re finishing stuff off after you’ve delivered the product, that’s Closing.

Q: Do you do all of the processes in every project?

A: Not always. Some of the processes apply only to projectized organizations or subcontracted work, so if your company doesn’t do that kind of thing, then you won’t need those processes. But if you want to make your projects come out well, then it really does make sense to use the processes. Even a small project can benefit from your taking the time to plan out the way you’ll handle all of the knowledge areas. If you do your homework and pay attention to all of the processes, you can avoid most of the big problems that cause projects to run into trouble!

Q: Can you use the same input in more than one process?

A: Yes. There are a lot of inputs that show up in multiple processes. For example, think about a schedule that you’d make for your project. You’ll need to use that schedule to build a budget, but also to do the work! So that schedule is an input to at least two processes. That’s why it’s really important that you write down exactly how you use each process, so you know what its inputs and outputs are.

Note

Your company should have records of all of these process documents, and the stuff the PMs learned from doing their projects. We call these things “organizational process assets,” and you’ll see a lot of them in the next chapter.

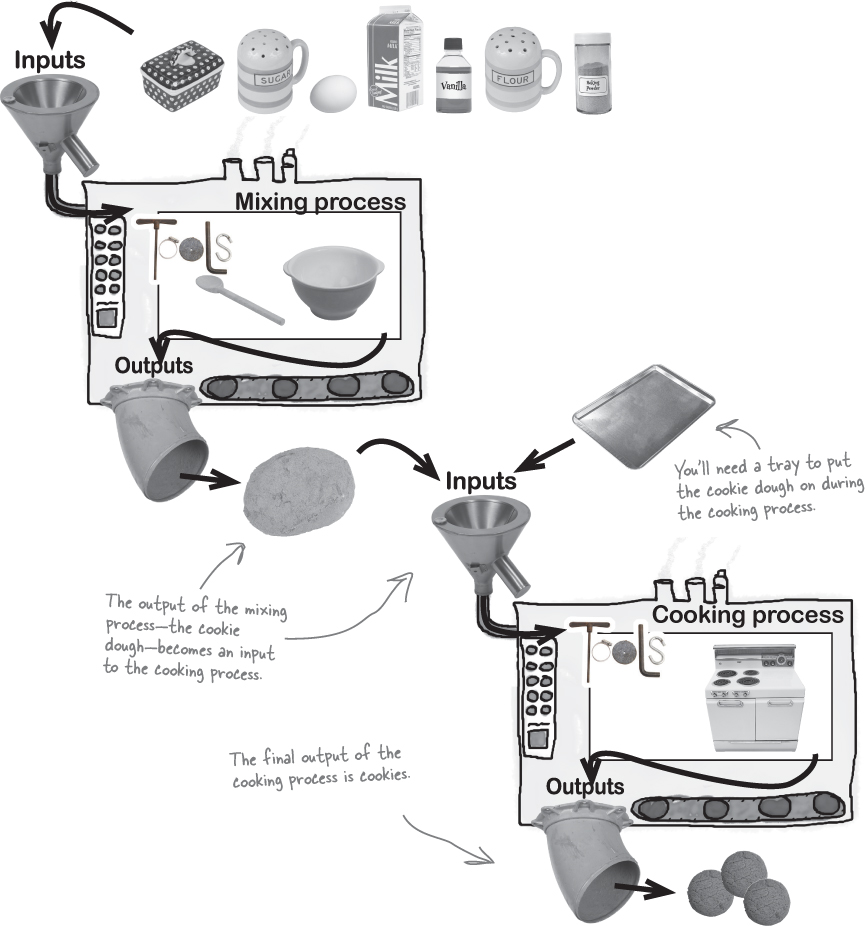

Combine processes to complete your project

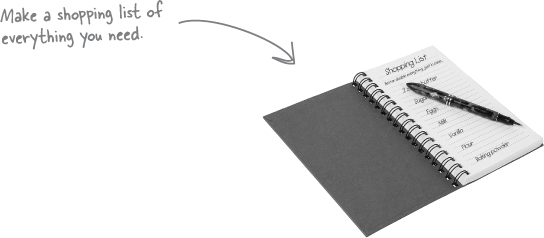

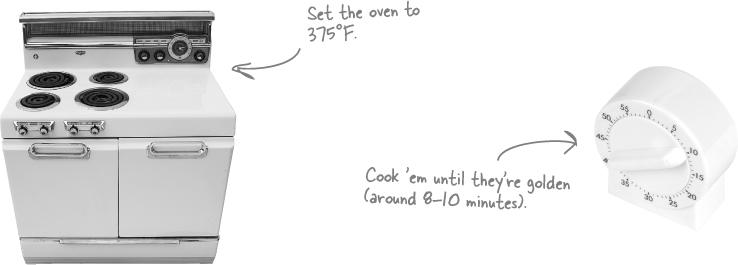

Sometimes the output of one process becomes an input of the next process. In the cookie project, the raw ingredients from the store are the outputs of the planning process, but they become the inputs for the executing process, where you mix the ingredients together and bake them:

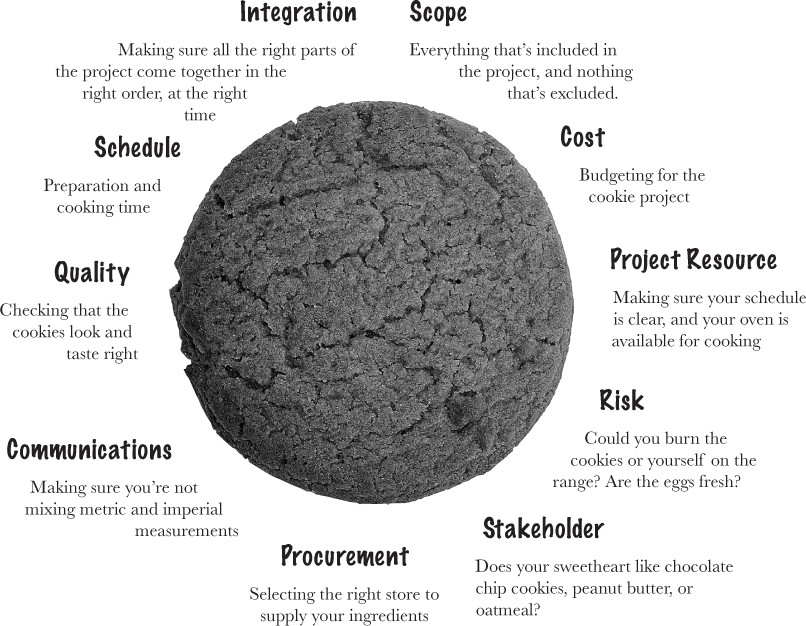

Knowledge Area Magnets

Match each of the 10 knowledge area magnets to each description. We’ve filled in a couple for you. (In the print editions of this book, this exercise—and several others—stretch across two pages.)

The Project Manager’s Role

Just like a cook uses a recipe, a project manager has to keep the big picture in mind and use all of the processes and knowledge areas to achieve a goal. But just understanding the process framework that will make your project successful isn’t enough. There are three major aspects to any project manager’s role, and all of them are equally important to a successful project. These three components make up the PMI Talent Triangle®.

It’s not enough to know processes you learn for the PMP exam. You’ve got to focus on leadership and strategic alignment to be a good PM!

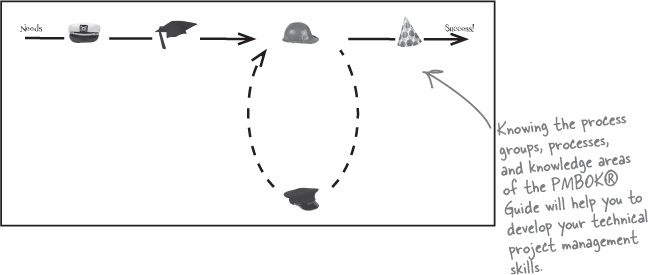

Your technical skills make successful projects happen

Just taking a look at the PMBOK® Guide makes it clear that there’s a lot to learn in the field of project management that can help you continuously improve your skills. Honing those skills will only help you and the project teams you work with to be more successful. But technical ability is just one part of a balanced project manager’s tool set. The more you learn and improve your skills, the more aware you become of your leadership style and how your project strategically helps your organization deliver value.

How does your project fit in?

Good project managers understand the strategic goals their projects are working toward and make decisions to help keep their projects aligned. The better you understand the organization that’s sponsoring your project, the more you’ll be able to help your organization achieve those goals. In many cases, project teams work with a number of other teams across their organization to accomplish their work, and a good project manager has a high-level view of how all of those teams fit together and collaborate to deliver products. Maintaining this overall understanding of the sponsoring organization and its strategic goals is what the PMI Talent Triangle® calls strategic and business management.

The more technical skills a project manager has, the more knowledge he or she can use to keep the project on target to achieve strategic goals. Likewise, the more a project manager understands about the way an organization works and its strategic goals, the better he or she can use technical skills to get the job done.

Leadership is different than management

Leaders inspire the teams they work with to do new and innovative things. They work with those teams to identify solutions to problems and support the team in thinking creatively. Leaders communicate the end goal and encourage their teams to find the best way to achieve it. On the other hand, managers try to control the variables that might lead to problems for their teams. Managers make decisions to maintain the team’s course and guide them in a prescriptive way.

Styles of leadership

Different styles of leadership will appeal to different teams and leaders. There are many factors that can influence which style of leadership a PM uses when working with a team, such as the organizational culture, the uncertainty of the problem the team is solving, and the interpersonal relationships on the team. Research on leadership has identified many different styles to choose from. Here are the six common leadership styles that are mentioned in the PMBOK® Guide because of their relevance to project management.

Laissez faire These leaders are “hands-off,” leaving most of the goal setting and daily leadership of the team to the team itself. They step in and make decisions only as a last resort. |

|

Transactional Leaders who are transactional make goals explicit and then track progress toward completing them. When the team’s actual progress deviates from the leader’s plan, he or she will provide course correction. |

Charismatic Charismatic leaders are inspiring because they hold strong convictions and have magnetic personalities. They use that inspiration to create a team culture that encourages innovation and aligns the team with those strongly held convictions and goals. |

|

Transformational Like charismatic leaders, transformational leaders focus on inspiring their teams with idealized goals. But transformational leaders encourage their teams to change the environment around them. Transformational leaders work to motivate each team member to be creative and make change happen. |

Interactional This type of leadership changes depending on the situation. Interactional leaders take whatever approach makes sense in the given situation. |

|

Servant leader This type of leadership is most often discussed in relation to agile thinking and methods. Here, a leader focuses on serving the people on the team. By clearing roadblocks and helping team members get what they need to achieve the group’s goal, the servant leader promotes better relationships on the team and creates a collaborative team culture. |

Project managers need to understand how power dynamics affect the team

The organization you work in has many different goals and agendas. To be a good project manager, you need to understand the goals and motivations of all of the stakeholders involved in your work. One useful tool for understanding the political playing field, and how decisions are being influenced around you, is to categorize the type of power your stakeholders are wielding.

Types of power

It’s clear that the CEO of your company has power over most of its employees just by virtue of the role he or she plays. There are many more subtle power relationships that develop in an organization that are not as easily identified. Here are some of the types of power people can exert when making decisions about your project:

Positional: The kind of power a CEO has; it exists because of the position or role someone is playing.

Informational: When someone knows something important that other people need.

Referent: When someone is trusted or judged as credible based on past experience.

Situational: When someone has skills specific to a situation that you’re in and you need his help.

Personal or charismatic: When someone has influence over you because you like her personality.

Relational: When someone has influence because he has an alliance with someone else who is influential.

Expert: When someone has influence because she’s demonstrated knowledge about something that you need.

Reward-oriented: When someone has influence because he can get you something you want or need.

Punitive or coercive: When someone has influence over you because she can cause problems for you if you don’t do what she wants.

Ingratiating: When someone has influence with you because he tells you that you’re great.

Pressure-based: When someone can create circumstances that make you seem out of step with the rest of the organization if you don’t comply with her requests.

Guilt-based: When someone appeals to your sense of honor or duty to get you to do what he wants.

Persuasive: When a person influences you by having a rational argument with you that changes your mind.

Avoiding: When a person withdraws her involvement in an issue in order to get desired behavior.

there are no Dumb Questions

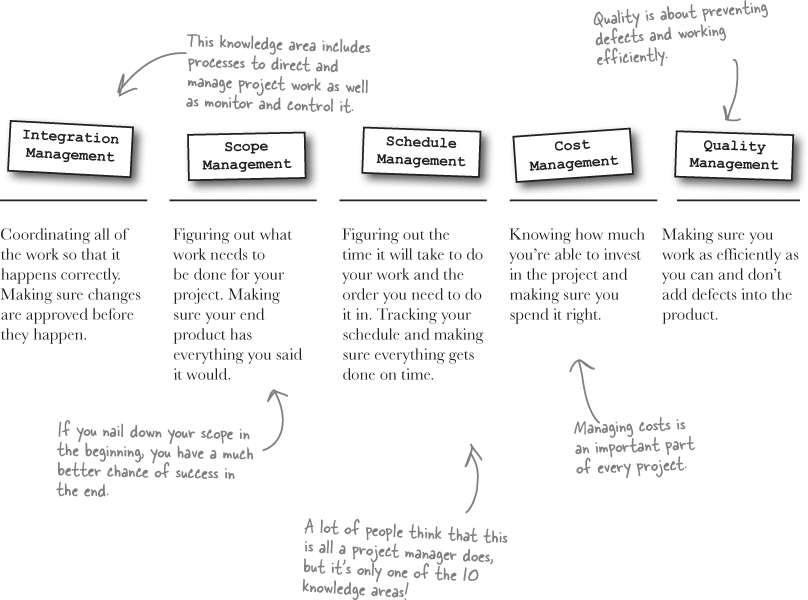

Q: So what’s the difference between process groups and knowledge areas?

A: The process groups divide up the processes by function. The knowledge areas divide up the same processes by subject matter. Think of the process groups as being about the actions you take on your project, and the knowledge areas as the things you need to understand.

In other words, the knowledge areas are more about helping you understand the PMBOK® Guide material than about running your project. But that doesn’t mean that every knowledge area has a process in every process group! For example, the Initiating process group has only two processes. The Risk Management knowledge area has only Planning and Monitoring and Controlling processes. So the process groups and the knowledge areas are two different ways to think about all of the processes, but they don’t really overlap.

Q: Is every knowledge area in only one process group?

A: Every process belongs to exactly one process group, and every process is in exactly one knowledge area. But a knowledge area has lots of processes in it, and they can span some, or all, of the groups. Think of the processes as the core information in the PMBOK® Guide, and the process groups and knowledge areas as two different ways of grouping these processes.

Q: It seems like the Initiating and Planning process groups would be the same. How are they different?

A: Initiating is everything you do when you first start a project (or project phase). You start by writing down (at a very high level) what the project is going to produce, who’s in charge of it, and what tools are needed to do the work...and lots of projects never get approved and chartered (which is an important goal of Initiating!). In a lot of companies, the project manager isn’t even involved in much of this. Planning just means going into more detail about all of that as you learn more about it, and writing down specifically how you’re going to do the work. The Planning processes are where the project manager is really in control and does most of the work.

Q: Let’s get back to the talent triangle for a minute. I’m a lot stronger in one of those areas than the others. What does that mean for me?

A: The PMI Talent Triangle® is a really valuable tool that helps you keep your own skill set in balance, and manage your professional development. Once upon a time, project management primarily involved technical skills: managing schedules, calculating costs, planning resources, managing changes, and so on. But PMI has done a lot of research in this area, and they’ve found that over the years—and especially over the last decade—technical skills are not enough to make a truly effective project manager in the modern enterprise. They found that the most effective project managers have a balance of technical, leadership, and strategic skills. But beyond research, the folks at PMI are committed to helping individual project managers. They developed the PMI Talent Triangle® to help you keep your own career in balance too.

Process groups and knowledge areas are two different ways to organize the processes...but they don’t really overlap each other! Don’t get caught up trying to make them fit together.

Exam Questions

You’re a project manager working on a software engineering project. Your manager is asking you to write down your performance goals for the year and measure them for your next performance evaluation. What leadership style is your manager using?

Charismatic

Interactional

Transactional

Performance

Which of the following is not a stakeholder?

The project manager who is responsible for building the project

A project team member who will work on the project

A customer who will use the final product

A competitor whose company will lose business because of the product

A project manager runs into a problem with her project’s contractors, and she isn’t sure if they’re abiding by the terms of the contract. Which knowledge area is the BEST source of processes to help her deal with this problem?

Cost Management

Risk Management

Procurement Management

Communications Management

You’re a project manager for a construction project. You’ve just finished creating a list of all of the people who will be directly affected by the project. What process group are you in?

Initiating

Planning

Executing

Monitoring and Controlling

You’re a project manager working in a weak matrix organization. Which of the following is NOT true?

Your team members report to functional managers.

You are not directly in charge of resources.

Functional managers make decisions that can affect your projects.

You have sole responsibility for the success or failure of the project.

Which of the following is NOT a project?

Repairing a car

Building a highway overpass

Running an IT support department

Filming a motion picture

A project manager is running a software project that is supposed to be delivered in phases. She was planning on dividing the resources into two separate teams to do the work for two phases at the same time, but one of her senior developers suggested that she use an agile methodology instead, and she agrees. Which of the following BEST describes the relationship between her project’s phases?

Sequential relationship

Iterative relationship

Constrained relationship

Overlapping relationship

Which of the following is NOT true about overlapping phases?

Each phase is typically done by a separate team.

There’s an increased risk of delays when a later phase can’t start until an earlier one ends.

There’s an increased risk to the project due to potential for rework.

Every phase must go through all five process groups.

You’re the project manager for an industrial design project. Your team members report to you, and you’re responsible for creating the budget, building the schedule, and assigning the tasks. When the project is complete, you release the team so they can work on other projects for the company. What kind of organization do you work in?

Functional

Weak matrix

Strong matrix

Projectized

Which process group contains the Develop Project Charter process and the Identify Stakeholders process?

Initiating

Executing

Monitoring and Controlling

Closing

Exam Answers

Answer: C

Transactional leaders set goals up front and then measure their team’s progress toward achieving them. Thinking about each activity that the team does as a transaction between the leader and the team is a good way to remember this leadership style.

Answer: D

One of the hardest things that a project manager has to do on a project is figure out who all the stakeholders are. The project manager, the team, the sponsor (or client), the customers and people who will use the software, the senior managers at the company—they’re all stakeholders. Competitors aren’t stakeholders, because even though they’re affected by the project, they don’t actually have any direct influence over it.

Answer: C

The Procurement Management knowledge area deals with contracts, contractors, buyers, and sellers. If you’ve got a question about a type of contract or how to deal with contract problems, you’re being asked about a Procurement Management process.

Answer: A

People who will be directly affected by the project are stakeholders, and when you’re creating a list of them you’re performing the Identify Stakeholders process. That’s one of the two processes in the Initiating process group.

Answer: D

In a weak matrix, project managers have very limited authority. They have to share a lot of responsibility with functional managers, and those functional managers have a lot of leeway to make decisions about how the team members are managed. In an organization like that, the project manager isn’t given a lot of responsibility.

Note

That’s why you’re likely to find a project expediter in a weak matrix.

Answer: C

The work of an IT support department doesn’t have an end date—it’s not temporary. That’s why it’s not a project. Now, if that support team had to work over the weekend to move the data center to a new location, then that would be a project!

Answer: B

Agile development is a really good example of an iterative approach to project phases. In an agile project, the team will typically break down the project into phases, where they work on the current phase while planning out the next one.

Answer: B

If there’s an increased risk of a project because one phase can’t start until another one ends, that means your project phases aren’t overlapping. When you’ve got overlapping phases, that means that you typically have multiple teams that start their phases independently of each other.

Also, take another look at answer C, because it’s an important point about overlapping phases. When your phases have an overlapping relationship, there’s an increased risk of rework. This typically happens when one team delivers the results of their project or phase, but made assumptions about what another team is doing as part of their phase. When that other team delivers their work, it turns out that the results that both teams produced aren’t quite compatible with each other, and now both teams have to go back and rework their designs. This happens a lot when your phases overlap, which is why we say overlapping phases have an increased risk of rework.

Answer: D

In a projectized organization, the project manager has the power to assign tasks, manage the budget, and release the team.

Answer: A

The first things that are created on a project are the charter (which you create in the Develop Project Charter process) and the stakeholder register (which you create in the Identify Stakeholders process). You do those things when you’re initiating the project.