Chapter 7. Cost management: Watching the bottom line

Every project boils down to money. If you had a bigger budget, you could probably get more people to do your project more quickly and deliver more. That’s why no project plan is complete until you come up with a budget. But no matter whether your project is big or small, and no matter how many resources and activities are in it, the process for figuring out the bottom line is always the same!

Time to expand Head First Kitchen

The Head First Kitchen is doing so well that their owners are going to go ahead and open a second location near you! They found a great location, and now all they need to do is renovate it.

The renovation goes overboard

When they start planning out what to buy, they want really expensive furniture and fixtures for the dining room—antique tables, luxury flooring, even a historic bar shipped in from another city. This is going to cost a lot of money…

Kitchen conversation

Tamika: That imported reclaimed wood flooring is amazing—and eco-friendly! I can just imagine how it will look.

Sue: And I found the perfect light fixtures made by hand by artisans in Brooklyn.

Alice: Look, I know you want the new Kitchen to look as good as the original, but you only have a little spare cash to spend on this. That means you have a limit of $10,000.

Sue: We should be able to get the new place looking amazing with that!

Alice: Costs can creep up on you if you don’t watch what you’re doing. The best way to handle this is to create a budget and check your progress against it as you go.

Tamika: You always turn everything into a project! Can’t you see that we have a vision?

Alice: Of course...but you don’t want that vision to drive you into the red.

Introducing the Cost Management processes

To make sure that they don’t go over budget, Tamika, Sue, and Alice sit down and come up with detailed estimates of their costs. Once they have that, they add up the cost estimates into a budget, and then they track the project according to that budget while the work is happening.

Plan Cost Management

Just like all of the other knowledge areas, you need to plan out all of the processes and methodologies you’ll use for Cost Management up front.

Estimate Costs

This means figuring out exactly how much you expect each work activity you are doing to cost. So each activity is estimated for its time and materials cost, and any other known factors that can be figured in.

Note

You need to have a good idea of the work you’re going to do and how long it will take to do that work.

Control Costs

This just means tracking the actual work according to the budget to see if any adjustments need to be made.

Note

Controlling costs means always knowing how you are doing compared to how you thought you would do.

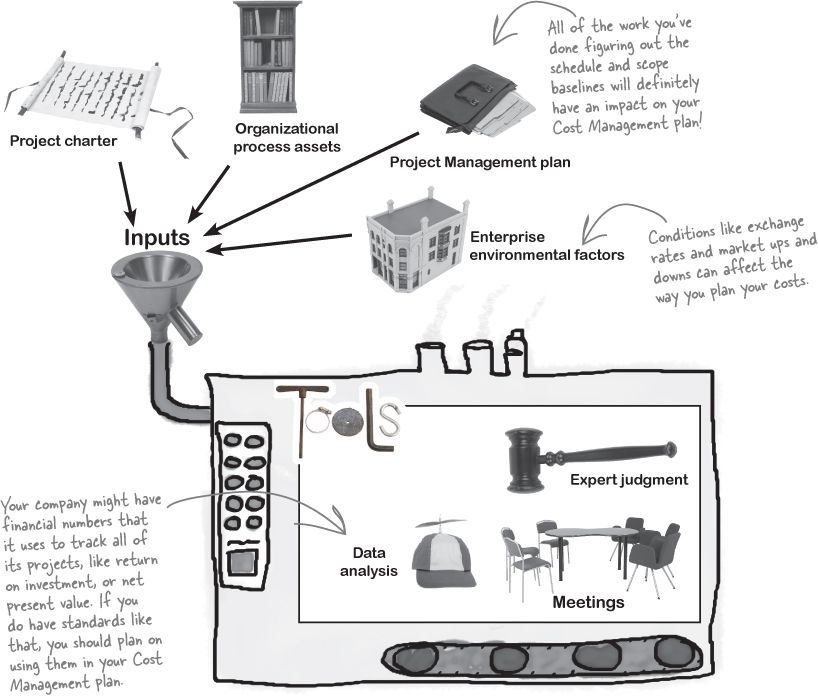

Plan how you’ll estimate, track, and control your costs

When you’ve got your project charter written and you’re starting to put together your Project Management plan, you need to think about all of the processes and standards you’ll follow when you estimate your budget and track to that estimate. By now, you’re pretty familiar with the inputs, outputs, tools, and techniques you’ll use in the Plan Cost Management process.

Now you’ve got a consistent way to manage costs

There’s only one output of the Plan Cost Management process, and that’s the Cost Management plan. You’ll use this document to specify the accuracy of your cost estimates, the rules you’ll use to determine whether or not your cost processes are working, and the way you’ll track your budget as the project progresses. When you’ve planned out your Cost Management processes, you should be able to estimate how much your project will cost using a format consistent with all the rest of your company’s projects. You should also be able to tell your management how you’ll know if your project starts costing more than you estimated.

Cost Management plan

Here’s where you write down the subsidiary plan inside the Project Management plan that deals with costs. You plan out all of the work you’ll do to figure out your budget and make sure your project stays within it.

Note

You’ll want to define the units you’ll use to manage your budget. For some projects, that’s total person-hours; for others, it’s an actual value in money. However you plan to track your costs, you need to let everybody on the project know up front.

The Plan Cost Management process is where you plan out all the work you’ll do to make sure your project doesn’t cost more than you’ve budgeted.

What Alice needs before she can estimate costs

Alice wants to keep the Kitchen project’s costs under control, and that starts with the Estimate Costs process. Before Alice can estimate costs, she needs the scope baseline. Once she knows who’s doing what work, and how long it’ll take, she can figure out how much it will cost.

Good question.

Not all of the estimation techniques for cost are the same as the ones we used for time. Often, people only have a certain amount of time to devote to a project, and a fixed amount of money too. So, it makes sense that some of the tools for estimating both would overlap. We’ll learn a few new ones next.

Other tools and techniques used in Estimate Costs

A lot of times you come into a project and there is already an expectation of how much it will cost or how much time it will take. When you make an estimate really early in the project and you don’t know much about it, that estimate is called a rough order of magnitude estimate. (You’ll also see it called a ROM or a ballpark estimate.) It’s expected that it will get more refined as time goes on and you learn more about the project. Here are some more tools and techniques used to estimate cost:

Note

This estimate is REALLY rough! It’s got a range of -25% to +75%, which means it can be anywhere from half to one and a half times the actual cost! So you only use it at the very beginning of the project.

Data analysis

These techniques are part of the data analysis necessary to create cost estimates:

Vendor bid analysis

Sometimes you will need to work with an external contractor to get your project done. You might even have more than one contractor bid on the job. This tool is all about evaluating those bids and choosing the one you will go with.

Reserve analysis

You need to set aside some money for cost overruns. If you know that your project has a risk of something expensive happening, it’s better to have some cash laying around to deal with it. Reserve analysis means putting some cash away just in case.

Cost of quality

You will need to figure the cost of all of your quality-related activities into the overall budget, too. Since it’s cheaper to find bugs earlier in the project than later, there are always quality costs associated with everything your project produces. Cost of quality is just a way of tracking the cost of those activities.

Project management information system

Project managers will often use specialized estimating software to help come up with cost estimates (like a spreadsheet that takes resource estimates, labor costs, and materials costs and performs calculations).

Decision making

You’ll need to work with groups of people to figure out your costs. It’s important that your team feels like they can commit to the overall budget and schedule.

Let’s talk numbers

There are a few numbers that can appear on the test as definitions. You won’t need to calculate these, but you should know what each term means.

Benefit-cost ratio (BCR)

This is the amount of money a project is going to make versus how much it will cost to build it. Generally, if the benefit is higher than the cost, the project is a good investment.

Note

You’ll get exam questions asking you to use BCR or NPV to compare two projects. The higher these numbers are, the better!

Net present value (NPV)

This is the actual value at a given time of the project minus all of the costs associated with it. This includes the time it takes to build it as well as labor and materials. People calculate this number to see if it’s worth doing a project.

Note

Money you’ll get in three years isn’t worth as much to you as money you’re getting today. NPV takes the “time value” of money into consideration, so you can pick the project with the best value in today’s dollars.

Opportunity cost

When an organization has to choose between two projects, it’s always giving up the money it would have made on the one it doesn’t do. That’s called opportunity cost. It’s the money you don’t get because you chose not to do a project.

Note

If a project will make your company $150,000, then the opportunity cost of selecting another project instead is $150,000 because that’s how much your company’s missing out on by not doing the project.

Internal rate of return

This is the amount of money the project will return to the company that is funding it. It’s how much money a project is making the company. It’s usually expressed as a percentage of the funding that has been allocated to it.

Depreciation

This is the rate at which your project loses value over time. So, if you are building a project that will only be marketable at a high price for a short period of time, the product loses value as time goes on.

Lifecycle costing

Before you get started on a project, it’s really useful to figure out how much you expect it to cost—not just to develop, but to support the product once it’s in place and being used by the customer.

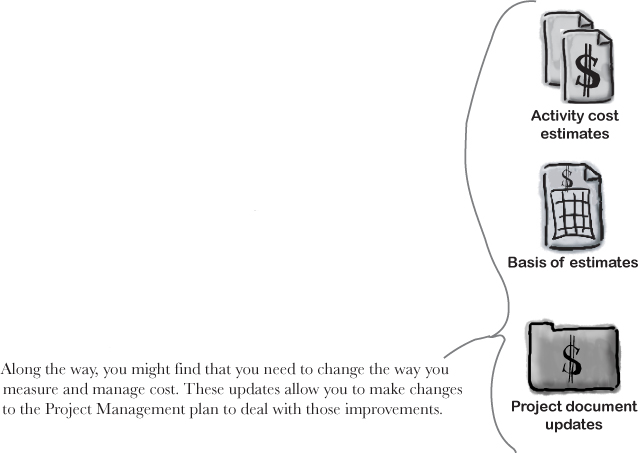

Now Alice knows how much the Kitchen will cost

Once you’ve applied all of the tools in the Estimate Costs process, you’ll get an estimate for how much your project will cost. It’s always important to keep all of your supporting estimate information, too. That way, you know the assumptions you made when you were coming up with your numbers.

Cost estimates

This is the cost estimate for all of the activities in your activity list. It takes into account resource rates and estimated duration of the activities.

Basis of estimates

Just like the WBS has a WBS dictionary, and the activity list has activity attributes, the cost estimate has a supporting detail called the basis of estimates. Here is where you list out all of the rates and reasoning you have used to come to the numbers you are presenting in your estimates.

Updates to project documents

Kitchen conversation

Tamika: OK, how do we start? There are a lot of things to buy here.

Alice: We already have your savings, and the rest will come in July at the end of the quarter. The Kitchen is having another great year, so the profits are pretty good. Your savings are around $4,000 and the profits will probably be closer to $6,000. That’s definitely enough money to work with.

Sue: Well, the furnishings I want aren’t back in stock until June.

Alice: OK, so we have to time our costs so that they’re in line with our cash flow.

Tamika: Oh! I see. So we can start building now, but we’ll still have money in June and July when the furnishings come in. Perfect.

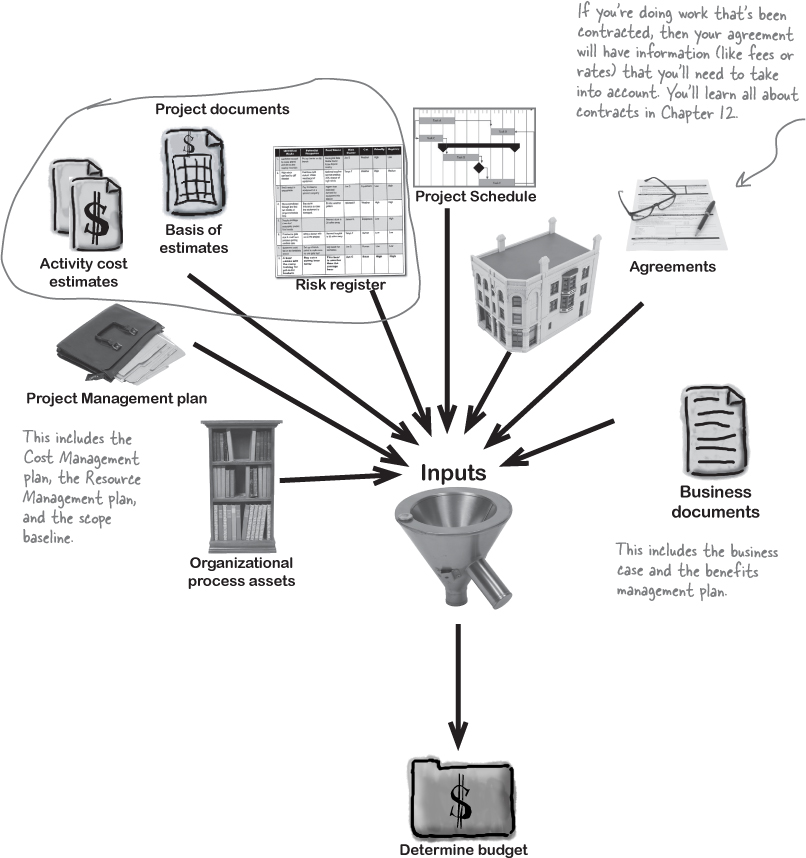

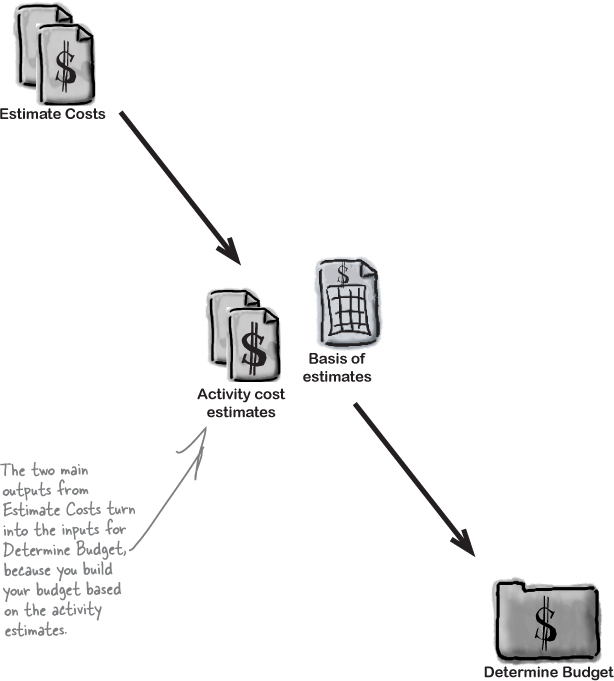

The Determine Budget process

Once Alice has cost estimates for each activity, she’s ready to put a budget together. She does that using the Determine Budget process. Here’s where you take the estimates that you came up with and build a budget out of them. You’ll build on the activity cost estimates and basis of cost estimates that you came up with in Estimate Costs.

You use the outputs from the last process, where you created estimates, as inputs to this one. Now you can build your budget.

Determine budget: how to build a budget

Roll up your estimates into control accounts.

This tool is called cost aggregation. You take your activity estimates and roll them up into control accounts on your work breakdown structure. That makes it easy for you to know what each work package in your project is going to cost.

Come up with your reserves.

When you evaluate the risks to your project, you will set aside some cash reserves to deal with any issues that might come your way. This tool is called data analysis.

Use your expert judgment.

Here’s where you compare your project to historical data that has been collected on other projects to give your budget some grounding in real-world historical information, and you use your own expertise and the expertise of others to come up with a realistic budget to cover your project’s costs.

Note

It’s true that not everybody has access to historical data to do a check like this. But, for the purposes of the test, you need to know that it’s a tool for making your budget accurate.

Make sure you haven’t blown your limits.

This tool is funding limit reconciliation. Since most people work in companies that aren’t willing to throw unlimited money at a project, you need to be sure that you can do the project within the amount that your company is willing to spend.

Note

If you blow your limit, you need to replan or go to your sponsor to figure out what to do. It could be that a scope change is necessary, or the funding limit can be increased.

Secure funding for your project.

This tool is financing. Since some companies go to external organizations to fund specific projects, you might need to meet special external requirements to get the financing. In this tool, you make sure you meet those requirements and get the finance commitments to make your project a success.

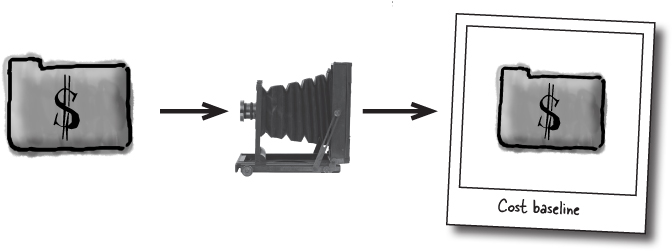

Build a baseline.

Just like your scope and schedule baselines, a cost baseline is a snapshot of the planned budget. You compare your actual performance against the baseline so you always know how you are doing versus what you planned.

Figure out funding requirements.

It’s not enough to have an overall number that everyone can agree to. You need to plan out how and when you will spend it, and document those plans in the project funding requirements. This output is about figuring out how you will make sure your project has money when it’s needed, and that you have enough to cover unexpected risks as well as known cost increases that change with time.

Note

So these requirements need to cover both the budget and the management reserve.

Update your Project Management plan and project documents.

Once you have estimated and produced your baseline and funding requirements, you need to update your Cost Management plan, Cost Baseline, Performance Measurement baseline with the new information you’ve obtained. You might have updates to project documents as well.

there are no Dumb Questions

Q: Isn’t it enough to know my project’s scope and schedule, and then trust the budget to come out all right?

A: Even if you don’t have a strict budget to work within, it makes sense to estimate your costs. Knowing your costs means that you have a good idea of the value of your project all the time. That means you will always know the impact (in dollars) of the decisions you make along the way. Sometimes understanding the value of your project will help you to make decisions that will keep your project healthier.

Many of us do have to work within a set of cost expectations from our project sponsors. The only way to know if you are meeting those expectations is to track your project against the original estimates.

It might seem like fluff. But knowing how much you are spending will help you relate to your sponsor’s expectations much better as well.

Q: In my job I am just handed a budget. How does estimating help me?

A: In the course of estimating, you might find that the budget you have been given is not realistic. It’s better to know that while you’re planning, before you get too far into the project work, rather than later.

You can present your findings to the sponsor and take corrective action right away if your estimate comes in pretty far off target. Your sponsor and your project team will thank you for it.

Q: What if I don’t have all of this information and I am supposed to give a ballpark estimate?

A: This is where those rough order of magnitude estimates come in. That’s just a fancy way of saying you take your best guess, knowing that it’s probably inaccurate, and you let everybody know that you will be revising your estimates as you learn more about the project.

Q: My company needs to handle maintenance of projects after we release them. How do you estimate for that?

A: That’s called lifecycle costing. The way you handle it is just like you handle every other estimate. You sit down and try to think of all of the activities and resources involved in maintenance, and project the cost. Once you have an estimate, you present it along with the estimate for initially building the product or service.

Q: I still don’t get net present value. What do I use it for?

A: The whole idea behind net present value is that you can figure out which of two projects is more valuable to you. Every project has a value—if your sponsor’s spending money on it, then you’d better deliver something worth at least that much to him! That’s why you figure out NPV by coming up with how much a project will be worth, and then subtracting how much it will cost. But for the exam, all you really need to remember are two things: net present value has the cost of the project built into it, and if you need to use NPV to select one of several projects, always choose the one with the biggest NPV. That’s not hard to remember, because you’re just choosing the one with the most value!

Note

Take a minute to think about what “value” really means. How does the sponsor know if he’s getting her money’s worth halfway through the project? Is there an easy way you can give the sponsor that information?

Q: Hold on just a minute. Can we go back to the rough order of magnitude estimate? I remember from my math classes that an order of magnitude has something to do with a fixed ratio. Wouldn’t –50% to +100% make more sense as an order of magnitude?

A: Yes, it’s true that in science, math, statistics, or engineering, an order of magnitude typically involves a series of magnitudes increasing by a fixed ratio. So if an order of magnitude down is 50%, then you’d typically maintain that same 2:1 ratio between orders of magnitude, so the next order of magnitude higher would be 100%.

However, the PMBOK® Guide defines it as follows: “a project in the initiation phase could have a rough order of magnitude (ROM) estimate in the range of –25% to +75%.” [5th Edition, p 201] Since that’s the definition in the PMBOK® Guide, that’s what to remember for the exam.

Estimate Costs is just like Estimate Activity Durations. You get the cost estimate and the basis of cost estimates, updates to the plan, and requested changes when you are done.

The Control Costs process is a lot like schedule control

When something unexpected comes up, you need to understand its impact on your budget and make sure that you react in the best way for your project. Just as changes can cause delays in the schedule, they can also cause cost overruns. The Control Costs process is all about knowing how you are doing compared to your plan and making adjustments when necessary.

A few new tools and techniques

The tools in Control Costs are all about helping you figure out where to make changes so you don’t overrun your budget.

Data Analysis

Earned value management

Here’s where you measure how your project is doing compared to the plan. This involves using the earned value formulas to assess your project.

Note

You’ll learn more about the formulas in just a few pages!

Performance reviews

Reviews are meetings where the project team reviews performance data to examine the variance between actual performance and the baseline. Earned value management is used to calculate and track the variance. Over time, these meetings are a good place to look into trends in the data.

Forecasting

Use the information you have about the project right now to predict how close it will come to its goals if it keeps going the way it has been. Forecasting uses some earned value numbers to help you come up with preventive and corrective actions that can keep your project on the right track.

Reserve analysis

Throughout your project, you are looking at how you are spending versus the amount of reserve you’ve budgeted. You might find that you are using reserved money at a faster rate than you expected or that you need to reserve more as new risks are uncovered.

Project management information system

You can use software packages to track your budget and make it easier to know where you might run into trouble.

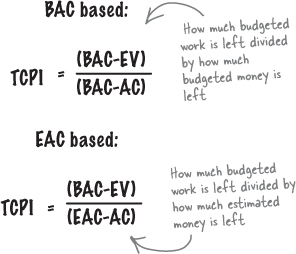

To-complete performance index

The to-complete performance index (TCPI) is a calculation that you can use to help you figure out how well your project needs to perform in the future in order to stay on budget.

Note

You’ll learn more about TCPI, too!

Look at the schedule to figure out your budget

The tools in Control Costs are all about helping you figure out where to make changes so you don’t overrun your budget.

Budget at completion (BAC)

How much money are you planning on spending on your project? Once you add up all of the costs for every activity and resource, you’ll get a final number…and that’s the total project budget. If you only have a certain amount of money to spend, you’d better make sure that you haven’t gone over!

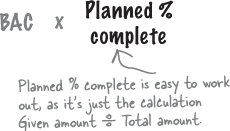

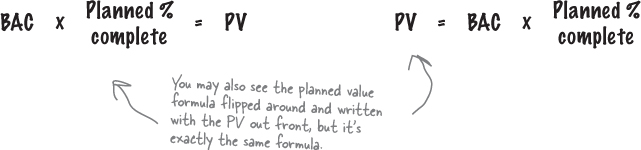

How to calculate planned value

If you look at your schedule and see that you’re supposed to have done a certain percentage of the work, then that’s the percent of the total budget that you’ve “earned” so far. This value is known as planned value. Here’s how you calculate it.

Note

Once you figure this out, you can figure out your project’s planned value.

First, write down your

BAC—Budget at completion

This is the first number you think of when you work on your project costs. It’s the total budget that you have for your project—how much you plan to spend on your project.

Then multiply that by your

Planned % complete

If the schedule says that your team should have done 300 hours of work so far, and they will work a total of 1,000 hours on the project, then your planned % complete is 30%.

The resulting number is your

PV—Planned value

This is how much of your budget you planned on using so far. If the BAC is $200,000, and the schedule says your planned % complete is 30%, then the planned value is $200,000 × 30% = $60,000.

Not yet, it doesn’t.

But wouldn’t be nice if, when your schedule said you were supposed to be 37.5% complete with the work, then you knew that you’d actually spent 37.5% of your budget?

Well, in the real world things don’t always work like that, but there are ways to work out—approximately—how far on (or off) track your budget actually is.

Earned value tells you how you’re doing

When Alice wants to track how her project is doing versus the budget, she uses earned value. This is a technique where you figure out how much of your project’s value has been delivered to the customer so far. You can do this by comparing the value of what your schedule says you should have delivered against the value of what you actually delivered.

Your schedule tells you a lot about where you are supposed to be right now.

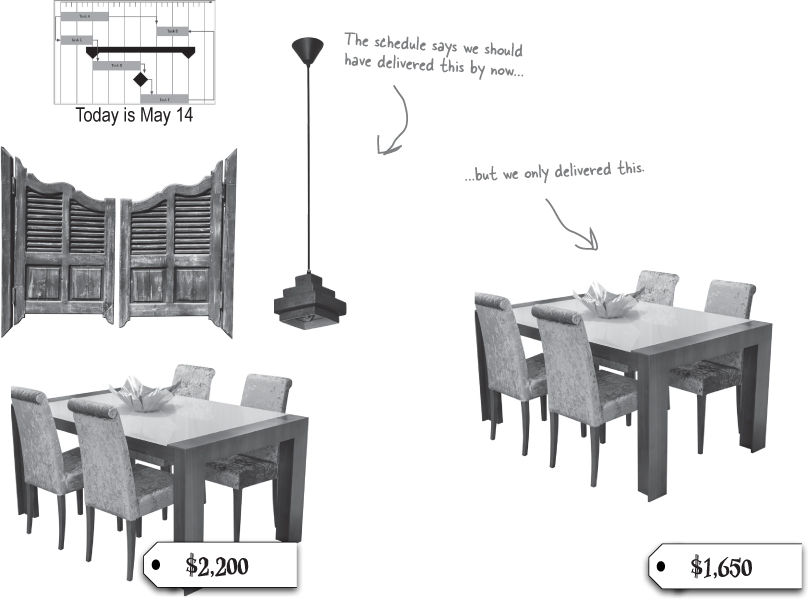

The actual cost of this project on May 14th is $1,650. The planned value was $2,200.

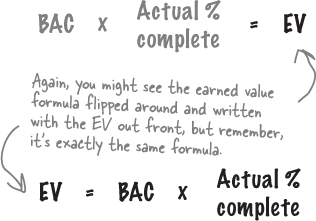

How to calculate earned value

If you could estimate each activity exactly, every single time, you wouldn’t need earned value. Your schedule would always be perfectly accurate, and you would always be exactly on budget.

But you know that real projects don’t really work that way! That’s why earned value is so useful—it helps you put a number on how far off track your project actually is. And that can be a really powerful tool for evaluating your progress and reporting your results. Here’s how you calculate it.

First, write down your

BAC—Budget at completion

Remember, this is the total budget that you have for your project.

BAC x

Then multiply that by your

Actual % complete

Say the schedule says that your team should have done 300 hours of work so far, out of a total of 1,000. But you talk to your team and find out they actually completed 35% of the work. That means the actual % complete is 35%.

The resulting number is your

EV—Earned value

This figure tells you how much your project actually earned. Every hour that each team member works adds value to the project. You can figure it out by taking the percentage of the hours that the team has actually worked and multiplying it by the BAC. If the total cost of the project is $200,000, then the earned value is $200,000 × 35% = $70,000.

Put yourself in someone else’s shoes

Earned value is one of the most difficult concepts that you need to understand for the PMP exam. The reason it’s so confusing for so many people is that these calculations seem a little weird and arbitrary to a lot of project managers.

But they make a lot more sense if you think about your project the way your sponsor thinks about it. If you put yourself into the sponsor’s shoes, you’ll see that this stuff actually makes sense!

Think about earned value from the sponsor’s perspective. It all makes a lot more sense then.

Let’s say you’re an executive:

You’re making a decision to spend $300,000 of your company’s money on a project. To a project manager, that’s a project’s budget. But to you, the sponsor, that’s $300,000 of value you expect to get!

Note

That’s the total budget, or the BAC.

You can definitely use them to track the schedule and budget on smaller projects.

But once your projects start getting more complex, your formulas are going to need to take into account that you’ve got several people all doing different activities, and that could make it harder to track whether you’re ahead of schedule or over budget.

So now that you know how to calculate PV and EV, they’re all you need to stay on top of everything. What are you waiting for? Flip the page to find out how!

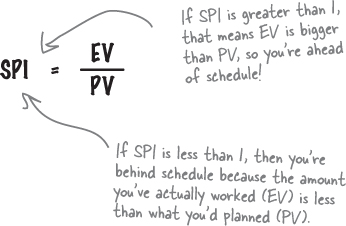

Is your project behind or ahead of schedule?

Figuring out if you’re on track in a small project with just a few people is easy. But what if you have dozens or hundreds of people doing lots of different activities? And what if some of them are on track, some are ahead of schedule, and some of them are behind? It starts to get hard to even figure out whether you’re meeting your goals.

Wouldn’t it be great if there were an easy way to figure out if you’re ahead or behind schedule? Well, good news: that’s exactly what earned value is used for!

Schedule performance index (SPI)

If you want to know whether you’re ahead of or behind schedule, use SPIs. The key to using this is that when you’re ahead of schedule, you’ve earned more value than planned! So EV will be bigger than PV.

To work out your SPI, you just divide your EV by your PV.

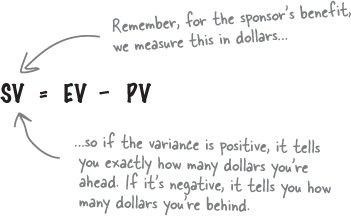

Schedule variance (SV)

It’s easy to see how variance works. The bigger the difference between what you planned and what you actually earned, the bigger the variance.

So, if you want to know how much ahead or behind schedule you are, just subtract PV from EV.

Are you over budget?

You can do the same thing for your budget that you can do for your schedule. The calculations are almost exactly the same, except instead of using planned value—which tells you how much work the schedule says you should have done so far—you use actual cost (AC). That’s the amount of money that you’ve spent so far on the project.

Note

Remember, EV measures the work that’s been done, while AC tells you how much you’ve spent so far.

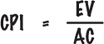

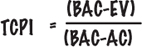

Cost performance index (CPI)

If you want to know whether you’re over or under budget, use CPI.

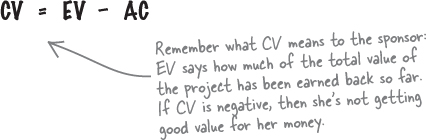

Cost variance (CV)

This tells you the difference between what you planned on spending and what you actually spent.

So, if you want to know how much under or over budget you are, just take AC away from EV.

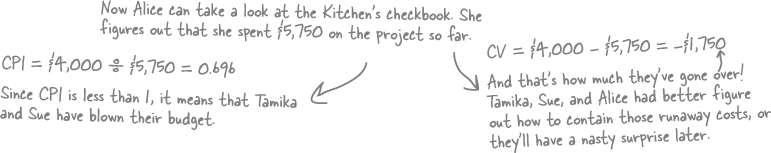

To-complete performance index (TCPI)

This tells you how well your project will need to perform to stay on budget.

Note

We’ll talk about this in just a few pages…

You’re within your budget if…

CPI is greater than or equal to 1 and CV is positive. When this happens, your actual costs are less than earned value, which means the project is delivering more value than it costs.

You’ve blown your budget if…

CPI is less than 1 and CV is negative. When your actual costs are more than earned value, that means that your sponsor is not getting her money’s worth of value from the project.

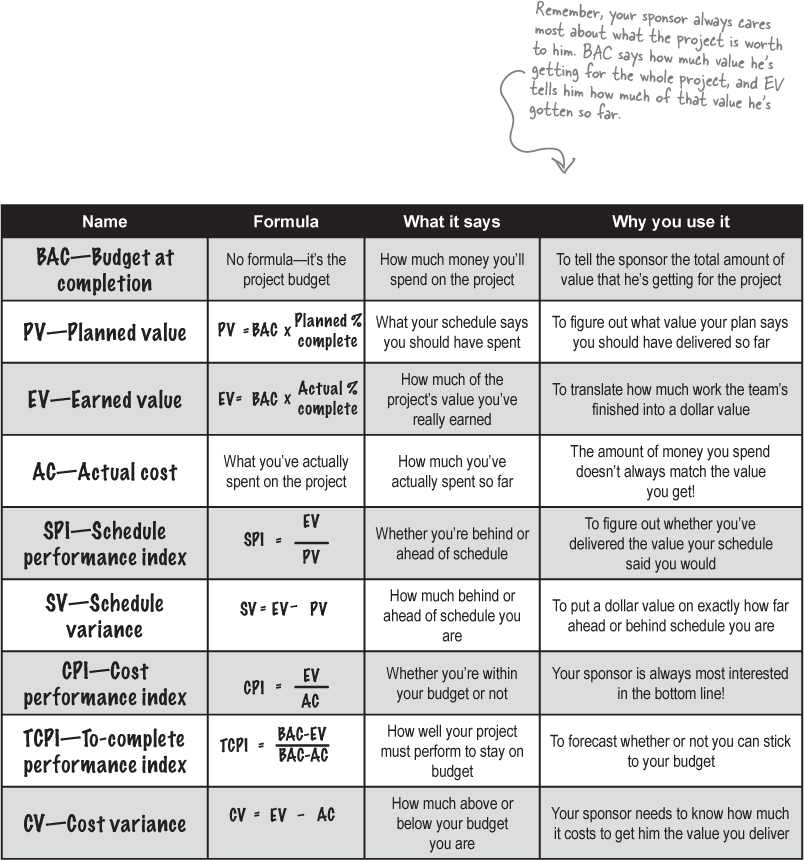

The earned value management formulas

Earned value management (EVM) is just one of the tools and techniques in the Control Costs process, but it’s a big part of PMP exam preparation. When you use these formulas, you’re measuring and analyzing how far off your project is from your plan. Remember, think of everything in terms of how much value you’re delivering to your sponsor! Take a look at the formulas one more time:

Interpret CPI and SPI numbers to gauge your project

The whole idea behind earned value management is that you can use it to easily put a number on how your project is doing. That’s why there will be exam questions that test you on your ability to interpret these numbers! Luckily, it’s pretty easy to evaluate a project based on the EVM formulas.

If the SPI is below 1, then your project is behind schedule. But if you see a CPI under 1, your project is over budget!

Exactly! And when your CPI is really close to 1, it means that every dollar your sponsor’s spending on the project is earning just about a dollar in value.

The biggest thing to remember about all of these numbers is that the lower they are, the worse your project is doing. If you’ve got an SPI of 1.1 and a CPI of 1.15, then you’re within your budget and ahead of schedule. But if you calculate a SPI of 0.6 and a CPI of 0.45, then you’re behind schedule and you’ve blown your budget. And when these ratios are below 1, then you’ll see a negative variance!

Remember:

Lower = Loser

If CPI or SPI is below 1, or if CV or SV is negative, then you’ve got trouble!

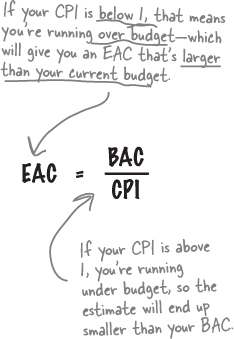

Forecast what your project will look like when it’s done

There’s another piece of earned value management, and it’s part of the last tool and technique in Cost Management: forecasting. The idea behind forecasting is that you can use earned value to come up with a pretty accurate prediction of what your project will look like at completion.

If you know your CPI now, you can use it to predict what your project will actually cost when it’s complete. Let’s say that you’re managing a project with a CPI of 0.8 today. If you assume that the CPI will be 0.8 for the rest of the project—and that’s not an unreasonable assumption when you’re far along in the project work—then you can predict your total costs when the project is complete. We call that estimate at completion (EAC).

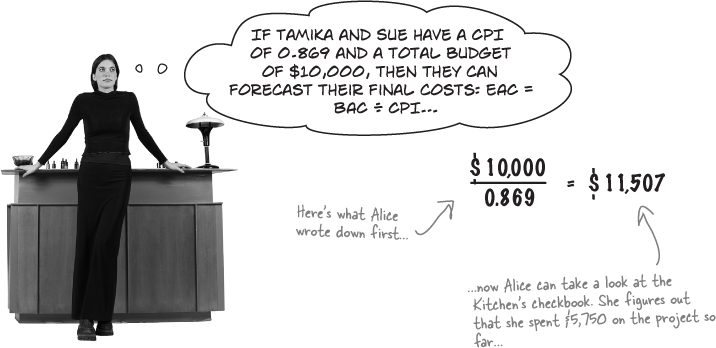

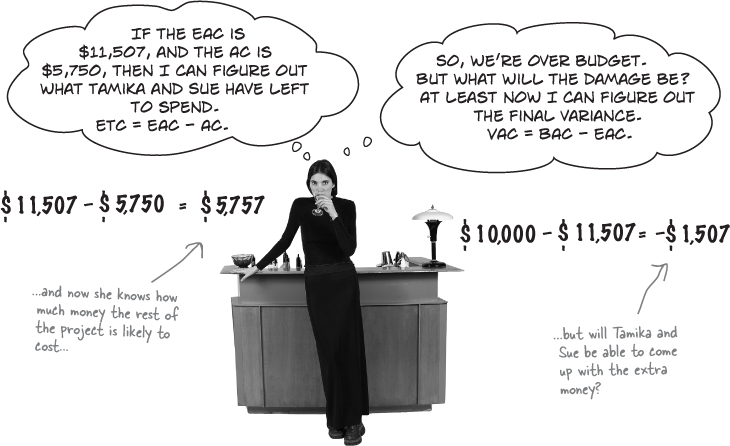

Meanwhile, back in the Kitchen

Alice is forecasting how the new Kitchen project will look when it’s done.

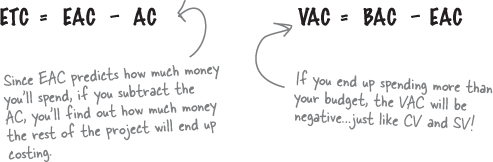

Once you’ve got an estimate, you can calculate a variance!

There are two useful numbers that you can compute with the EAC. One of them is called estimate to complete (ETC), which tells you how much more money you’ll probably spend on your project. And the other one, variance at completion (VAC), predicts what your variance will be when the project is done.

You can use EAC, ETC, and VAC to predict what your earned value numbers will look like when your project is complete.

there are no Dumb Questions

Q: What does CPI really mean, and why can it predict your final budget?

A: Doesn’t it seem a little weird that you can come up with a pretty accurate forecast of what you’ll actually spend on your project just by dividing CPI into your BAC, or the total amount that you’re planning to spend on the project? How can there be one “magic” number that does that for you?

But when you think about it, it actually makes sense. Let’s say that you’re running 15% over budget today. If your budget is $100,000, then your CPI will be $100.000 ÷ $115,000 = .87. One good way to predict what your final budget will look like is to assume that you’ll keep running 15% over budget. Let’s say your total budget is $250,000. If you’re still 15% over at the end of the budget, your final CPI will still be $250,000 ÷ $287,500 = .87! Your CPI will always be .87 if you’re 15% over budget.

That’s why we call that forecast EAC—it’s an estimate of what your budget will look like at completion. By dividing CPI into BAC, all you’re doing is calculating what your final budget will be if your final budget overrun or underrun is exactly the same as it is today.

Q: Is that really the best way to estimate costs? What if things change between now and the end of the project?

A: EAC is a good way to estimate costs, because it’s easy to calculate and relatively accurate—assuming that nothing on the project changes too much. But you’re right, if a whole lot of unexpected costs happen or your team members figure out a cheaper and better way to get the job done, then an EAC forecast could be way off!

It turns out that there are over 25 different ways to calculate EAC, and the one in this chapter is just one of them. Some of those other formulas take risks and predictions into account. But for the PMP exam, you just need to know

EAC = BAC ÷ CPI.

Q: Wow, there are a lot of earned value formulas! Is there an easy way to remember them?

A: Yes, there are a few ways that help you remember the earned value formulas. One way is to notice that the performance reporting formulas all have something either being divided into or subtracted from EV. This should make sense—the whole point of earned value management is that you’re trying to figure out how much of the value you’re delivering to your sponsor has been earned so far. Also, remember that a variance is always subtraction, and an index is always division. The schedule formulas SV and SPI both involve PV numbers you got from your schedule, while the cost formulas CV and CPI both involve AC numbers from your budget.

And remember, the lower the index or variance, the worse your project is doing! A negative variance or an index that’s below 1 is bad, while a positive variance or an index that’s above 1 is good!

The earned value formulas have numbers divided into or subtracted from EV. SV and SPI use PV, while CV and CPI use AC.

Keep your project on track with TCPI

You can use earned value to gauge where you need to be to get your project in under budget. TCPI can help you find out not just whether or not you’re on target, but exactly where you need to be to make sure you get things done with the money you have.

Note

Have you ever wondered halfway through a project just how much you’d have to cut costs in order to get it within your budget? This is how you figure that out!

To-complete performance index (TCPI)

This number represents a target that your CPI would have to hit in order to hit your forecasted completion cost. If you’re performing within your budgeted cost, it’ll be based on your BAC. If you’re running over your budget, you’ll have to estimate a new EAC and base your TCPI on that.

There are two different formulas for TCPI. One is for when you’re trying to get your project within your original budget, and the other is for when you are trying to get your project done within the EAC you’ve determined from earned value calculations.

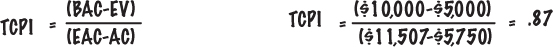

TCPI for the Head First Kitchen renovation project

Alice figured out the BAC and EAC for the project and realized that the Kitchen was over budget, so she did a TCPI calculation to figure out exactly where she needed to keep her CPI if she wanted to get the project in without blowing the budget. Alice’s earned value calculations have put the renovation project’s numbers here:

The project is over budget! So Alice uses the BAC-based formula to figure out where she needs to keep the CPI for the project if she wants to complete it within the original budget. Here’s the calculation:

So, if the project were going to get back on budget, it would have to run at a 1.17 CPI for the rest of the project to make up for the initial overage. Alice doesn’t think that’s going to happen. Tamika and Sue pushed for an antique tin ceiling in the dining room that cost an extra $750 in the beginning, and, the way things are going, it’s probably a safe bet that there will be a few more cost overruns like that as the project goes on. She prepared a second TCPI to see what the numbers would be to complete the project based on the current EAC.

A high TCPI means a tight budget

When you’re looking at the TCPI for a project, a higher number means it’s time to take a stricter cost management approach. The higher the number, the more you’re going to have to rein in spending on your project and cut costs. When the number is lower than 1, you know you’re well within your budget and you can relax a bit.

Note

Remember “lower = loser”? Well, with TCPI, it’s the opposite. A higher number means that your budget is too tight. You want it lower to give you more room to spend money!

Party time!

Tamika and Sue finished the new Kitchen! It looks great, and they’re really happy about it…because Alice managed their costs well. She used earned value to correct their budget problems, and they managed to cut a few costs while they still had time. And they had just enough money left over at the end to throw a great opening party!

Exam Questions

You are creating your cost baseline. What process are you in?

Determine Budget

Control Costs

Estimate Costs

Cost Baselining

You’re working on a project that has an EV of $7,362 and a PV (BCWS) of $8,232. What’s your SV?

Note

Some of the earned value numbers have alternate four-letter abbreviations. This one stands for “budgeted cost of work scheduled.” Don’t worry—you don’t need to memorize them!

–$870

$870

0.89

Not enough information to tell

You are managing a project for a company that has previously done three projects that were similar to it. You consult with the cost baselines, lessons learned, and project managers from those projects, and use that information to come up with your cost estimate. What technique are you using?

Parametric estimating

Net present value

Rough order of magnitude estimation

Analogous estimating

You are working on a project with a PV of $56,733 and an SPI of 1.2. What’s the earned value of your project?

$68,079.60

$47,277.50

$68,733

.72

Your company has two projects to choose from. Project A is a billing software project for the Accounts Payable department; in the end it will make the company around $400,000 when it has been rolled out to all of the employees in that department. Project B is a payroll application that will make the company around $388,000 when it has been put to use throughout the company. After a long deliberation, your board chooses to go ahead with Project B. What is the opportunity cost for choosing Project B over Project A?

$388,000

$400,000

$12,000

1.2

Your company has asked you to provide a cost estimate that includes maintenance, installation, support, and upkeep costs for as long as the product will be used. What is that kind of estimate called?

Benefit-cost ratio

Depreciation

Net present value

Lifecycle costing

You are working on a project with an SPI of .72 and a CPI of 1.1. Which of the following BEST describes your project?

Your project is ahead of schedule and under budget.

Your project is behind schedule and over budget.

Your project is behind schedule and under budget.

Your project is ahead of schedule and over budget.

Your project has a BAC of $4,522 and is 13% complete. What is the earned value (EV)?

$3,934.14

There is not enough information to answer.

$587.86

$4,522

A project manager is working on a large construction project. His plan says that the project should end up costing $1.5 million, but he’s concerned that he’s not going to come in under budget. He’s spent $950,000 of the budget so far, and he calculates that he’s 57% done with the work, and he doesn’t think he can improve his CPI above 1.05. Which of the following BEST describes the current state of the project?

The project is likely to come in under budget.

The project is likely to exceed its budget.

The project is right on target.

There is no way to determine this information.

You are managing a project laying underwater fiber optic cable. The total cost of the project is $52/meter to lay 4 km of cable across a lake. It’s scheduled to take eight weeks to complete, with an equal amount of cable laid in each week. It’s currently the end of week 5, and your team has laid 1,800 meters of cable so far. What is the SPI of your project?

1.16

1.08

.92

.72

During the execution of a software project, one of your programmers informs you that she discovered a design flaw that will require the team to go back and make a large change. What is the BEST way to handle this situation?

Ask the programmer to consult with the rest of the team and get back to you with a recommendation.

Determine how the change will impact the project constraints.

Stop all work and call a meeting with the sponsor.

Update the cost baseline to reflect the change.

If AC (ACWP) is greater than your EV (BCWP), what does this mean?

The project is under budget.

The project is over budget.

The project is ahead of schedule.

The project is behind schedule.

A junior project manager is studying for her PMP exam, and asks you for advice. She’s learning about earned value management, and wants to know which of the variables represents the difference between what you expect to spend on the project and what you’ve actually spent so far. What should you tell her?

Actual cost (AC)

Cost performance index (CPI)

Earned value (EV)

Cost variance (CV)

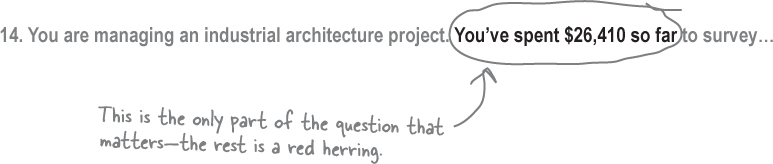

You are managing an industrial architecture project. You’ve spent $26,410 so far to survey the site, draw up preliminary plans, and run engineering simulations. You are preparing to meet with your sponsor when you discover that there is a new local zoning law that will cause you to have to spend an additional estimated $15,000 to revise your plans. You contact the sponsor and initiate a change request to update the cost baseline.

What variable would you use to represent the $26,410 in an earned value calculation?

PV

BAC

AC

EV

You are working on the project plan for a software project. Your company has a standard spreadsheet that you use to generate estimates. To use the spreadsheet, you meet with the team to estimate the number of functional requirements, use cases, and design wireframes for the project. Then you categorize them into high, medium, or low complexity. You enter all of those numbers into the spreadsheet, which uses a data table derived from past projects’ actual costs and durations, performs a set of calculations, and generates a final estimate. What kind of estimation is being done?

Parametric

Rough order of magnitude

Bottom-up

Analogous

Project A has an NPV of $75,000, with an internal rate of return of 1.5% and an initial investment of $15,000. Project B has an NPV of $60,000 with a BCR of 2:1. Project C has an NPV of $80,000, which includes an opportunity cost of $35,000. Based on these projects, which is the BEST one to select:

Project A

Project B

Project C

There is not enough information to select a project.

What is the range of a rough order of magnitude estimate?

–5% to +10%

–25% to +75%

–50% to +50%

–100% to +200%

You are managing a software project when one of your stakeholders needs to make a change that will affect the budget. What defines the processes that you must follow in order to implement the change?

Perform Integrated Change Control

Monitoring and Controlling process group

Change control board

Cost baseline

You are managing a software project when one of your stakeholders needs to make a change that will affect the budget. You follow the procedures to implement the change. Which of the following must get updated to reflect the change?

Project Management plan

Project cost baseline

Cost change control system

Project performance reviews

You are managing a project with a BAC of $93,000, EV (BCWP) of $51,840, PV (BCWS) of $64,800, and AC (ACWP) of $43,200. What is the CPI?

Note

Again, don’t panic if you see these four-letter abbreviations. You’ll always be given the ones you’re used to on the exam!

1.5

0.8

1.2

$9,000

You are managing a project that has a TCPI of 1.19. What is the BEST course of action?

You’re under budget, so you can manage costs with lenience.

Manage costs aggressively.

Create a new schedule.

Create a new budget.

You are starting to write your project charter with your project sponsor when the senior managers ask for a time and cost estimate for the project. You have not yet gathered many of the project details. What kind of estimate can you give?

Analogous estimate

Rough order of magnitude estimate

Parametric estimate

Bottom-up estimate

You are managing a project for a defense contractor. You know that you’re over budget, and you need to tell your project sponsor how much more money it’s going to cost. You’ve already given him a forecast that represents your estimate of total cost at the end of the project, so you need to take that into account. You now need to figure out what your CPI needs to be for the rest of the project. Which of the following BEST meets your needs?

BAC

ETC

TCPI (BAC calculation)

TCPI (EAC calculation)

Exam Answers

Answer: A

This is really a question about the order of the processes. Control Costs uses the cost baseline, so it has to be created before you get to it. Cost Baselining isn’t a process at all, so you should exclude that from the choices right away. The main output of Determine Budget is the cost baseline and supporting detail, so that’s the right choice here.

D. Cost Baselining

Note

Watch out for fake processes! This isn’t a real process name.

Answer: A

This one is just testing whether or not you know the formula for schedule variance. Just plug the values into the SV formula: SV = EV – PV and you get answer A. Watch out for negative numbers, though! Answer B is a trap because it’s a positive value. Also, the test will have answers like C that check if you’re using the right formula. If you use the SPI formula, that’s the answer you’ll get! You can throw out D right away—you don’t need to do any calculation to know that you have enough information to figure out SV!

Answer: D

When you’re using the past performance of previous projects to help come up with an estimate, that’s called analogous estimation. This is the second time you’ve seen this particular technique—it was also in Chapter 6. So there’s a good chance that you’ll get an exam question on it.

Answer: A

The formula for SPI is: SPI = EV ÷ PV. So you just have to fill in the numbers that you know, which gets you 1.2 = EV ÷ $56,733. Now flip it around. You end up with EV = 1.2 × $56,733, which multiplies out to $68,079.60.

Answer: B

Note

Did you notice the red herring in the question? It didn’t matter what the projects were about, only how much they cost!

If you see a question asking the opportunity cost of selecting one project over another, the answer is the value of the project that was not selected! So even though the answers were all numbers, there’s no math at all in this question.

-

This is one of those questions that gives you a definition and asks you to pick the term that’s being defined. So which one is it?

Try using the process of elimination to find the right answer! It can’t be benefit-cost ratio, because you aren’t being asked to compare the overall cost of the project to anything to figure out what its benefit will be. Depreciation isn’t right—that’s about how your project loses value over time, not about its costs. And it’s not net present value, because the question didn’t ask you about how much value your project is delivering today. That leaves lifecycle costing.

Note

If you don’t know the answer to a question, try to eliminate all the answers you know are wrong.

Answer: C

Note

Don’t forget: Lower = Loser!

When you see an SPI that’s lower than 1, that means your project is behind schedule. But your CPI is above 1, which means that you’re ahead on your budget!

Answer: C

Use the formula: EV = BAC × actual % complete. When you plug the numbers into the formula, the right answer pops out!

Answer: B

You might not have recognized this as a TCPI problem immediately, but take another look at the question. It’s asking you whether or not a project is going to come in under budget, and that’s what TCPI is for. Good thing you were given all of the values you need to calculate it! The actual % complete is 57%, the BAC is $1,500,000, and the AC is $950,000. You can calculate the EV = BAC × actual % complete = $1,500,000 × 57% = $855,000. So now you have everything you need to calculate TCPI: this means he needs a TCPI of 1.17 in order to come in under budget. Since he knows that he can’t get better than 1.05, he’s likely to blow the budget.

Answer: D

Some of these calculation questions can get a little complicated, but that doesn’t mean they’re difficult! Just relax—you can do them!

The formula you need to use is: SPI = EV ÷ PV. But what do you use for EV and PV? If you look at the question again, you’ll find everything you need to calculate them. First, figure out earned value: EV = BAC × actual % complete. But wait! You weren’t given these in the question!

OK, no problem—you just need to think your way through it. The project will cost $52/meter to lay 4 km (or 4,000 meters) of cable, which means the total cost of the project will be $52 × 4,000 = $208,000. And you can figure out actual % complete too! You’ve laid 1,800 meters so far out of the 4,000 meters you’ll lay in total…so that’s 1,800 ÷ 4,000 = 45% complete. All right! Now you know your earned value: EV = $208,000 × 45% = $93,600.

So what’s next? You’ve got half of what you need for SPI—now you have to figure out PV. The formula for it is: PV = BAC × scheduled % complete. So how much of the project were you supposed to complete by now? You’re five weeks into an eight-week project, so 5 ÷ 8 = 62.5%. Your PV is $208,000 × 62.5% = $130,000. Now you’ve got everything you need to calculate SPI! EV ÷ PV = $93,600 ÷ $130,000 = .72

Note

Did you think that this was a red herring? It wasn’t—you needed all the numbers you were given.

Answer: B

You’ll run into a lot of questions like this where a problem happens, a person has an issue, or the project runs into trouble. When this happens, the first thing you do is stop and gather information. And that should make sense to you, since you don’t know if this change will really impact cost or not. It may seem like a huge change to the programmer, but may not actually cost the project anything. Or it may really be huge. So the first thing to do is figure out the impact of the change on the project constraints, and that’s what answer B says!

-

What formula do you know that has AC and EV? Right: the CPI formula does! Take a look at it: CPI = EV ÷ AC. So what happens if AC is bigger than EV? Make up two numbers and plug them in. You get CPI that’s below 1, and you know what that means…it means that you’ve blown your budget!

Answer: D

This question gave you a definition and is checking to see if you know what it refers to. You should take a minute to look at the four possible answers and see if you can think of the definition for each of them. It’s definitely worth taking the time to understand what each of these formulas and variables represents in real life! It will make the whole exam a lot easier.

Answer: C

This is a classic red herring question! The money you’ve spent so far is the actual cost. It’s a simple definition question, wrapped up in a whole bunch of fluff!

Answer: A

When you plug a bunch of values into a formula or computer program, and it generates an estimate, that’s called parametric estimation. Parametric estimation often uses some historical data, but that doesn’t mean it’s the same as analogous estimation.

Answer: C

You’ve been given a net present value (NPV) for each project. NPV means the total value that this project is worth to your company. It’s got the costs—including opportunity costs—built in already. So all you need to do is select the project with the biggest NPV.

Answer: B

The rough order of magnitude estimate is a very preliminary estimate that everyone knows is only within an order of magnitude of the actual cost (or –25 to +75%).

Answer: A

You should definitely have a pretty good idea of how change control works by now! The change control system defines the procedures that you use to carry out the changes. And Control Costs has its own set of procedures, which are part of the Perform Integrated Change Control process you learned about in Chapter 4.

Answer: B

You use the project cost baseline to measure and monitor your project’s cost performance. The idea behind a baseline is that when a change is approved and implemented, the baseline gets updated.

Answer: C

You should have the hang of this by now! Plug the numbers into the formula (CPI = EV ÷ AC), and it spits out the answer. Sometimes the question will give you more numbers than you actually need to use—just ignore them like any other red herring and use only the ones you need!

Answer: B

If your TCPI is above 1, you need to manage costs aggressively. This means that you need to meet your goals without spending as much money as you have been for the rest of the project.

Answer: B

If you are just starting to work on your project charter, it means you’re just starting the project and you don’t have enough information yet to do analogous, parametric, or bottom-up estimates.

The only estimation technique that you can use that early in the project is the rough order of magnitude estimate. That kind of estimate is not nearly as accurate as the other kinds of estimate and is used just to give a rough idea of how much time and cost will be involved in doing a project.

Answer: D

This question may have seemed a little wordy, but it’s really just a question about the definition of TCPI. You’re being asked to figure out where you need to keep your project’s CPI in order to meet your budget. And you know it’s the EAC-based TCPI number, because the question specified that you already gave him a forecast, which means you gave him an EAC value already. So now you can calculate the EAC-based TCPI number to figure out where you need to keep your CPI for the rest of the project.

Note

By calculating this based on the EAC, you show your sponsor just how much money he needs to kick in (or less, if you’ve got good news!) in order to come in under budget.