2

LAKE VILLAGE

Lake Village has served as the seat of Chicot County since 1857. It sits on Lake Chicot, the largest oxbow lake in North America. If you’ve read Classic Eateries of the Ozarks and Arkansas River Valley, you may already know its claim to fame. It goes back to Italy, to New York banker Austin Corbin’s purchase of the Sunnyside Plantation and his arrangement for immigrants from Rome to populate the settlement. It ends hundreds of miles away in northwest Arkansas, with the establishment of Tontitown. The middle of the story lies in this agrarian community.

After Father Pietro Bandini and the thiry-five families who followed him to northwest Arkansas established Tontitown, Bandini sent word to Italy for another minister for the people of Sunnyside. That fell to Father F.J. Galloni, who arrived on the plantation a short time later and who would eventually move to Lake Village proper.

Italians were also recruited to other plantations in the area. When Lake Village was officially incorporated in 1898 (the same year as Tontitown), its makeup included many of those Italian settlers as well as whites and blacks whose families had lived there long before.

Italian heritage is still celebrated in Lake Village each March with the annual spaghetti dinner at Our Lady of the Lake Church. The celebration takes weeks of preparation, with bread baked and egg-yolk noodles made in January and the Pierini family rolling 3,600 meatballs every February. The whole community contributes to the making of desserts.

A FRIED CHICKEN HISTORY

The immigrants who followed Father Bandini to Tontitown took with them not only their own spaghetti but also fried chicken, the latter being a part of Delta custom long before their arrival. Born of similar dishes brought across the South by both African and Scottish ancestors, the traditional fried chicken served as “Sunday’s best” is still prevalent today.

Mind you, the original meat of Arkansas was pork, because pigs can be raised anywhere, on anything. Yardbird was a special-occasion food, something you ended up bringing to the church social. Fried chicken was considered “Yankee Dinner”—a term used first by nineteenth-century newspaperman William Minor “Cush” Quesenbury, who called visiting northerners “chicken-eaters.”

Most settlers from Europe were accustomed to having their chicken roasted or stewed. The Scots are believed to have brought the idea of frying chicken in fat to the United States and eventually into the Arkansas Delta in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Similarly, African slaves brought to the South were sometimes allowed to keep chickens, which didn’t take up much space. They flour-breaded their pieces of plucked poultry, popped it with paprika and saturated it with spices before putting it into the grease. Frying in lard or oil is quicker than baking and could be done in a cast-iron vessel over a fire or on a stove. It didn’t take long for that propensity for jointing and processing chicken with the skin on; dipping it in flour, buttermilk and egg; and dropping into a hot skillet to take hold.

Chicken was battered and fried in southeast Arkansas for decades before the arrival of those Italian immigrants who bought into Sunnyside Plantation. But they picked it up quickly once they arrived. Those who didn’t move on to Tontitown would remain in Sunnyside for the duration, and just like with Peter St. Columbia up in Helena, they shared their Italian gastronomic identity by adapting the dish.

Today, you can still find pretty dang good fried chicken around the area. JJ’s Café (which was JJ’s Lakeside Café until it moved into town) still offers an excellent version on its lunch buffet. There are fast-food versions, too. And then there’s the fried chicken at a restaurant known not for that dish, but for tamales.

RHODA’S FAMOUS HOT TAMALES, LAKE VILLAGE

In April 1923, Lake Village became the site of famed aviator Charles Lindbergh’s first nighttime flight.

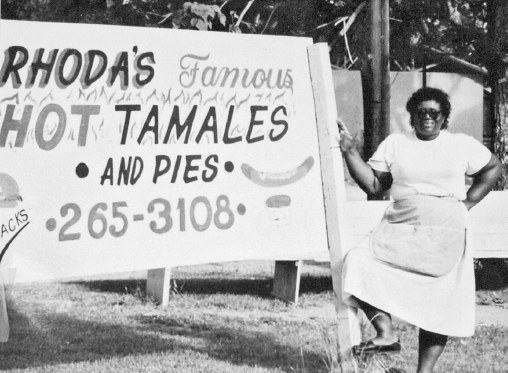

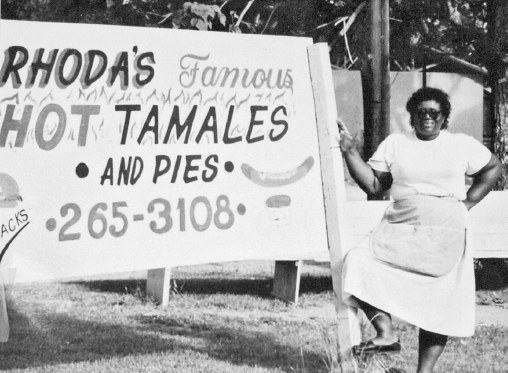

There’s been many a time I ended up on the doorstep of Rhoda Adams, the proprietress of a local establishment in Lake Village known as Rhoda’s Famous Hot Tamales. She and her husband, James, run this place on Saint Mary’s Street, and you can smell it a block away, the scent of spices and fried things luring you off the highway.

On one trip in March 2011, Grav and I picked up a dozen tamales in a paper sack from Rhoda on the way to New Orleans. We got on down the road, going through Eudora to hit Interstate 20 in Tallulah, Louisiana. Not far from Mound, traffic came to a dead stop. We waited on the pavement a while, and when traffic scooted up to a state trooper standing by the road, we asked him what was going on. Turns out a barge had hit the Mississippi Bridge at Vicksburg, and an inspector was on the way to make sure it was safe.

Rhoda Adams has been making tamales and pies at her establishment in Lake Village since 1973. Courtesy JJ’s Café.

We did what most anyone would do—pulled off the road and waited in the one spot where there was space—the parking lot of an adult store. Being hungry, we dug into that sack of tamales.

We tore open that bag to find an aluminum foil–wrapped bundle. Through that, there was newspaper—a lot of it. I unwound the newspaper to find another aluminum foil–wrapped bundle, and through that there was wax paper and more aluminum foil and a paper boat that had all but disintegrated from the juice of a dozen cornhusk-wrapped beef-and-chicken-fat tamales. With no utensils in the car, we ate the tamales with our fingers. At that moment, it was the best thing I’d ever eaten in my life.

Rhoda knows her tamales are good. She never made a tamale in her life until someone said she should. That night, her family sat up together making tamales, wrapping them in cornhusks and tieing them until the wee hours. The next day she sold every single one. She still usually sells them all, but that’s partly because she’s such a good saleswoman. Every day except Sunday, Rhoda gets up and packs hot tamales a dozen in a bag, three dozen in a coffee can, as many as she thinks she can part with, and puts them in her van. She then drives around town selling them. She goes to the RV parks, to the banks of Lake Chicot and to the parking lot of home furnishings legend Paul Michael’s (where staffers will tell you how she honks, sometimes until customers vacate the store) and sells them. Then she heads back to her restaurant for the lunch rush.

Rhoda started with sweet potato pie (Arkansas Pie: A Delicious Slice of the Natural State will tell you more about that). She’s famous for her tamales, not just because they’re good but because she does good press. She can also talk the legs off a mule; I was in town with a group of my colleagues a few years ago, determined not to take home more than one of those little three-inch pies for lunch. I walked in, got my lunch and she told me I was going to buy one of her half-and-half pecan and sweet potato pies. And she was right, I did.

But Rhoda’s also a master of another Arkansas staple: fried chicken. It’s an exquisite, salty, juicy, orange-gold bird meant for consumption with white bread and sweet potatoes, preferably with sweet tea.

She started the operation in 1973, and a fair number of folks have come through in all those years—from television producers and politicians to regular folks like you and me. And she’s still convincing folks to walk out of her establishment full, happy and with a pie to go.

You can see Rhoda’s husk-wrapped tamales on the back cover of this book.

KOWLOON RESTAURANT, LAKE VILLAGE

In several cities across the Arkansas Delta, you’ll find Chinese restaurants that have been open for decades, run by the descendants of immigrants who came looking for the fabled Gaam San, or Golden Mountain. They settled along the Mississippi River Delta and Crowley’s Ridge. Some stuck with agricultural work but many opened small grocery stores, and after the stores came the restaurants. Cantonese flavors are still popular with diners throughout the Arkansas Delta.

In Lake Village, there remains Kowloon Restaurant. Back in the 1970s, the Lee family operated a small grocery store in town. But Arthur “Pat” Lee realized that when other larger grocery stores such as Yee’s Food Giant moved in he wouldn’t be able to keep up. He’d had a hand in a restaurant in Little Rock, the Hong Kong Restaurant on Cantrell Road, and he decided to give it a shot in Lake Village. Kowloon opened February 24, 1977, and is still going strong.

Locals came in and liked what they ate, and news spread. Today, the Mongolian beef, sweet-and-sour chicken and all the favorites of traditional Chinese restaurants are offered here. Pat’s son, Arthur Lee Jr., still runs the place and says all that’s really changed is that the menu has been simplified a little over the years.

The name of the restaurant? The senior Lee hailed from Hong Kong, which is where the Little Rock’s restaurant got its name. Kowloon is named for Mrs. Lee’s hometown.

Kowloon Restaurant in Lake Village. Grav Weldon.

THE COW PEN, LAKE VILLAGE

Lake Chicot, on which Lake Village sits, is the largest oxbow lake in North America and the largest natural lake in Arkansas. It formed when the Mississippi River changed its channel, leaving behind a crescent-shaped body of water known for its crappie, largemouth bass and channel catfish. It gets its name from the French word for “stumpy,” thanks to all the cypress trees and knees along the lake’s banks.

Lake Village is where U.S. Highways 65 and 82 pair up before they dance across the Mississippi on what is now the longest cable-stayed bridge across Big Muddy at Greenville. At the foot of the new Greenville Bridge lies an old cattle inspection station that’s been renovated, burned out and renovated again. This is the Cow Pen, purveyor of some of the best steaks you’ll find in the Delta, and home of the Chip and Dip.

Floyd Owens bought the old station back in 1967 and turned it into something new. He started a restaurant to serve the folks coming across the old Benjamin G. Humphreys Bridge from Greenville. Ten years later, he turned it over to Gene and Juanita Grassi, who ran it for thirty years. They added other items, ranging from catfish to Mexican fare to the Italian dishes popular in the area.

The Grassis decided to retire in 2007 and handed the reins over to Charles Faulk and his family. Sadly, six months later the place burned out. That didn’t deter the Faulks, who dove into the task of rebuilding it bigger and better. Since reopening in November 2008, the place has flourished.

You can’t really get a seat in the place Friday and Saturday nights, not right away at least. Within the wood-clad walls of the place, folks pack every section. I’ve seen parties there of grown men with the charisma of little boys, telling stories and bragging over their steaks. I’ve seen elegantly dressed individuals pile in after weddings and gamblers who’ve crossed the bridge looking for something not served in a casino.

There was even a time when I came looking for sustenance and found it in the form of Chip and Dip—a palatial basket of fresh-fried, thin tortilla chips served with six-ounce metal ramekins of housemade bean dip, housemade salsa and bright yellow cheese dip.

The Cow Pen Restaurant in Lake Village. Grav Weldon.

Any Tuesday through Saturday night (or any Sunday lunch), you might see Big Charles, Teresa, Little Charles, Lydia, Ed, Cookie, Angela, Jose, Bill or Sue Anne. Everyone’s on a first-name basis, and you might as well be home.

BELOW LAKE VILLAGE

Lake Village lies at a crossroads. In 1918, the first section of Arkansas Highway A-3 was completed through town; this became part of U.S. Highway 65 when it was created in 1926. Arkansas Highway 2 once crossed the city, tied to Greenville on one side and all the way to Texarkana on the other. It became U.S. Highway 82 in 1932.

Not far from the city’s western border you’ll find Bayou Bartholomew, the longest bayou in the world. This 364-mile-long body of water separates the Delta’s long, unbroken plain with the densely wooded Timberlands of this state—the border of the area covered by this book.

There aren’t many restaurants in Chicot County outside of Lake Village—a handful in Eudora (none very old) and a few in Dermott (including Willy’s Old Fashioned Hamburgers, once a popular burger stop). Way down U.S. Highway 165 there’s a little town called Wilmot that hugs the bayou where you’ll find Country Cupboard, open for decades in a little dilapidated building across the street from the railroad tracks.

Most eateries lie along or not far from U.S. Highway 65 on the western side of the Lower Delta. Let’s head that way.