6

ROCK ‘N’ ROLL HIGHWAY 67

To the south of Little Rock at the heart of the state, there’s the first roll of the Ouachitas and the wooded sections of timber all the way to Pine Bluff. South from there, Bayou Bartholomew’s run down to the Louisiana border gives a neat line to delineate the Lower Delta from points westerly.

North of Little Rock, there’s more of a blending of the Ozark’s last rolling hills with the sometimes swampy, sometimes forested edges of the Grand Prairie. Once you get to Searcy, where U.S. Highway 67 crosses the Little Red River, the separation is more defined. The four-lane expressway rolls over a few languishing hills into Bald Knob before paralleling the last low ridge of the Ozarks up to Newport. The old highway, still demarcated as U.S. Highway 67 for now but destined to join other old highway sections as Arkansas Highway 367 in the future, keeps that ridge in view all the way to Pocahontas, where it skirts that ridge by a block before heading northeast to Corning and out into Missouri.

U.S. Highway 67 is as good a line as any to note the end of the Delta’s reach and what I use here to separate it from the Ozarks. There are a few places between this line and the limit of what I covered in Classic Eateries of the Ozarks and Arkansas River Valley, and I’ll share those in the final section of this book.

U.S. Highway 67 was created in 1926 along with the bones of the initial federal highway system, over the route of the original Southwest Trail that lead frontiersmen from St. Louis to Texas. Its original route from Frederickstown, Missouri, to Dallas, Texas, has been extended; the Texas route goes to Presidio and becomes Mexican Federal Highway 16 on the other side of the Rio Grande, while the north end now terminates at Sabula, Iowa. In southern Arkansas it follows most of its original path with exceptions around Donaldson and between Benton and Little Rock. North of Pulaski County, its original alignment lies mostly along Arkansas Highway 367, which runs east of the current U.S Highway 67 expressway to Searcy before crossing through the heart of town and up along the edge of the Ozarks to just south of Swifton, where the abrupt end of the expressway is tied back to the original highway via a two-lane highway. The White River runs between the two sections south of Newport for several miles.

Plans are to eventually expand the expressway all the way to the Missouri border; however, the state’s lack of plans to tie in the expressway to its northern line has left little hurry to getting the rest of the job done. A lone expressway section in Walnut Ridge loops trucks around the city from U.S. Highway 63.

There is a section remaining of the original U.S. Highway 67 pavement, which dates back to 1929, between Alicia and Hoxie. You’ll often see people fishing from bridges along the stretch during the warmer months.

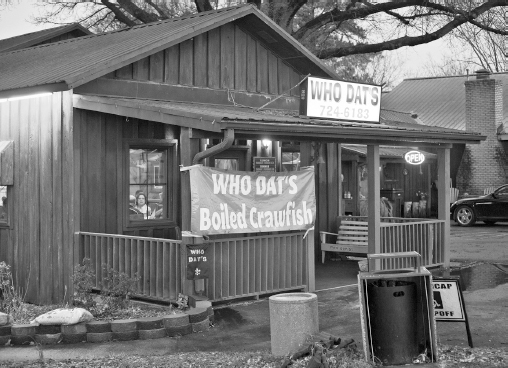

WHO DAT’S, BALD KNOB

Bald Knob is a good place to start when you’re talking about the Upper Delta. Situated at the intersection of U.S. Highways 64, 67 and 167, it’s also at the foot of the first rolling hills of the Ozarks. Set off north along U.S. Highway 167, and the roads quickly begin to curl and bob along the first ridges. Head east along U.S. Highway 64, and it’s a straight-flat roll all the way to West Memphis with just a few hops over rivers and swings around old downtowns. Go south and you race through wooded lands to Little Rock.

Before heading north, there are three restaurants to mention. The first is the old Kelley’s Restaurant, which has family ties to an existing operation in Wynne and a now-closed restaurant in Batesville. The second ties in with the first. It owes its origins to several things, including a fading southern Louisiana oil industry, a failed start-up business and Kelley’s.

It all started with Doug Stelly. Back in southern Louisiana, in a little place called Abbieville, the young man learned to cook when he was seven and grew up immersed in Cajun cookery. As a young adult, he worked his way up from dishwasher to manager of an Abbieville steakhouse and then started his own eatery. When the oil business dried up around the area, his restaurant dried up, too.

Who Dat’s Cajun Restaurant in Bald Knob. Grav Weldon.

Fortuitously, a Bald Knob restaurant owner passing through the area got Stelly’s name and asked him to come up to Arkansas to keep the place going. It didn’t work out, and Stelly was back to square one.

It didn’t take long being back in Louisiana for Stelly to realize that Bald Knob was the place he really wanted to be, so he headed back north and took a job with Sam Kelley at Kelley’s Restaurant. A short time later, Stelly and his wife, Sam, bought a hamburger stand and had their own restaurant.

What they discovered, though, was that people in Bald Knob had liked the Cajun cooking from that other restaurant operation and they wanted it back. Unable to get financing, the couple cleared out the backyard and built an eatery right onto the back of their house. Thus in 1992, Who Dat’s was born.

The restaurant has expanded several times, but still, on Friday and Saturday nights you’ll see people camped out around the porch and picnic tables in the parking lot, waiting for a chance to get in, for good reason. The crawfish etouffee, fried frog legs, gumbo and every other item comes from old family recipes. The Stellys’ five kids and even both their mothers have been involved in the operation.

When you see all those folks patiently waiting for a chance to get inside the doors to a table for blackened catfish, fried shrimp and jambalaya, it’s hard to believe that Who Dat’s doesn’t advertise. It’s all word-of-mouth, and fortunately for Doug and Sam Stelly and their kin, it’s been good.

When you go, be ready to wait. If you have a big appetite or just want to graze, have yourself the Food Bar—a combination salad station and Sunday-style potluck that includes white rice, red beans and rice with sausage, smothered chicken with Creole spices, butterbeans cooked with tomatoes, corn on the cob, blackeyed peas, green beans with bacon, barbecue baked beans, home fries, carrots, English peas, baked chicken and corn off the cob. Of course, that’s entirely sidestepping the fantastically prepared seafood and Cajun and Creole favorites, but it’s the cheap choice and a good feast.

THE BULLDOG DRIVE IN, BALD KNOB

The third restaurant in Bald Knob is usually at the top of travelers’ lists, especially late in the spring. The Bulldog Drive In was opened in 1978 by Bob Miller, who raised the money for his fledgling enterprise by working summers during high school and college on a pipeline. He spent his first two years after college working on the Transatlantic Alaskan Pipeline. Other restaurants had operated in the building where he constructed his dream; they’d all failed, but Miller was determined to succeed. He even took on the name of the last restaurant that tried to make it there. The Bulldog, after all, refers to the Bald Knob high school mascot. Miller’s wife, Lece, worked there when she was in high school.

It wasn’t easy in the beginning, but the restaurant did eventually develop a following of local folks who were thrilled with a reasonably priced drive-in that offered pit barbecue, burgers and cheap plate-lunch specials.

However, out-of-towners make the special stop in through the late spring and summer months because of a very special item—the restaurant’s famed strawberry shortcake. This isn’t a fluffy pound cake version, and it’s not served on biscuits like many Arkansas home cooks do it. Miller’s grandmother’s recipe is still used to make the shortcake, which is rolled out and baked. It’s thin, and it’s served covered in fresh strawberries and their juices. You can have it with whipped cream, nuts and even ice cream. But you can’t have it in the fall and winter. Miller uses mostly local berries but stretches the season a little if he can get fresh berries from within the United States. Typically that means you can get the delightful dessert between April Fool’s Day and Labor Day.

The Bulldog Drive In in Bald Knob. Grav Weldon.

RHYTHM ROAD

In 2009, the Arkansas legislature, through Act 497, designated 111 miles of the original U.S. Highway 67 as Rock ’N’ Roll Highway 67 through Jackson, Lawrence, Randolph and Clay Counties. This stretch of the highway was the site of numerous juke joints, roadhouses, theaters and dives between the end of the Second World War and the 1980s. The last of these, the King of Clubs, burned in 2010. Elvis Presley performed there, as did Johnny Cash, who once got up and sang three songs for twenty dollars on the stage inside the undistinguished white building near Swifton.

The others—including the King’s Capri, Sunset Inn, Bloody Bucket, 67 Club, Sunset Inn, Jarvis’s and Silver Moon—were incubators for a whole new line of American music. It’s where many early rock-and-roll stars first cut their teeth. In addition to Presley and Cash, other acts such as Jerry Lee Lewis, Sonny Burgess, Billy Lee Riley and Conway Twitty sang their hearts out and tried new tunes in front of those crowds. Notes of blues, gospel and even country blended together with the fledgling rock sound to produce another of Arkansas’s native forms—rockabilly, a term created by crossing rock with hillbilly.

The long stretch of pavement tying the miles together offered a quick route to musical bliss for decades. Today, the joints themselves are celebrated at Newport’s Rock ’N’ Roll Highway 67 Museum.

SMOKEHOUSE BBQ AND LACKEY’S TAMALES, NEWPORT

I’ve already shared the origins of the Arkansas Delta tamale, and of the chicken-fat-and-beef creations made by Ms. Rhoda Adams in Lake Village. There is yet a third set of tamales that you should consider when criss-crossing the Delta. Those would be the Cajun-style chicken-filled maize rolls known as Lackey’s Tamales.

Mind you, if you start looking around Newport for a restaurant called Lackey’s, you’re not going to find it. The eatery that bore the name and a sign out front that proclaimed, “Lackey’s Cajun Style Hot Tamales” is gone. Fortunately there’s still one bastion of spicy tamale goodness out there: a little restaurant on the south side of town, a diminutive place called Smokehouse BBQ.

Smokehouse BBQ in Newport. Grav Weldon.

We went on a stormy Friday night in March 2014. It was packed. We were told to go find a seat, and a waitress brought out a thick menu with every sort of Southern delight on it—a full slate of breakfast; barbecue plates of chopped beef, pork and pork ribs; Cajun and steak plates featuring Omaha steaks; tamale plates loaded with chili and cheese; Cajun staples of red beans and rice, gumbo and jambalaya; catfish and shrimp plates with lobster tail and crab leg add-ons; lunch and dinner specials and Happy Hour specials; chicken plates and salads and gator bites; burgers and po’ boys and a Philly cheesesteak. Amidst the appetizers, a bright orange block proclaimed, “Lackey’s Tamales, Cajun-Style chicken tamales wrapped in cornhusk,” with one, six or twelve in an order.

Grav had never had a Lackey’s tamale before, and his fondness for Rhoda’s and Pasquale’s tamales kept his excitement down. He was interested in the Cajun cheese dip and got it, but I got a word in and asked the waitress to bring him just one. She admitted to me a heresy—she doesn’t eat tamales, since her dad used to eat the sort out of a can (the shame), but knew they were good. She retrieved the ordered items while we decided on dinner.

We had just about decided to split a big barbecue combo plate between the two of us when she set the tamale down in front of him and, after photographing the thing, Grav took a timid bite. Then it was gone. He even changed his order (leaving me with a barbecue beef sandwich to consume) and asked for one-half dozen more Lackey’s tamales, announcing he’d finally found something spicy enough for his taste. The less-greasy tamale (Rhoda does use chicken fat, as you now know) that bore the Lackey name was packed with shredded chicken and a hell of a lot of spices, both Cajun and Mexican in flavor. Combined with masa, it had the flavor of a strong Frito chili pie.

Grav was just as enamored, if not more so, with the cheese dip. Touched, swallowed, gobbled, licked the bowl—these terms all apply to what Grav was doing to that sausage- and spice-packed bowl of cheese dip. When he ran out of chips he dolloped the dip onto his tamales. He sweated. The sweat rolled from the top of his head to the neck of his shirt, and he still could not get enough of it. He lauded it, calling it the best cheese dip he had ever tasted. He wiped his brow. He ate more. He inhaled those tamales and that cheese dip and would have rented an extra stomach if possible to be able to keep passing more of that spicy food through his lips. All of this amused me.

Newport native Sonny Burgess became a big name for Sun Records out of Memphis. The lead singer for several bands, including the Rocky Road Ramblers and the Moonlighters, eventually settled down heading the Pacers. He’s shared the stage with Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, Charlie Rich, Jerry Lee Lewis and Conway Twitty, among others. Sonny Burgess and the Pacers were inducted into the Rockabilly Hall of Fame in 2002.

I had myself an order of fries and that jumbo barbecue beef sandwich topped with a dollop of coleslaw. It came with very little sauce, which I augmented with more from the table squeeze bottle, its flavor a cross between the thick sweet sauce of Old Post BBQ in Russellville and the tang of Sims Bar-B-Que’s sauce from Little Rock. This barbecue juice was as thick as ketchup and on the orange side of brown, and it stuck to the meat with fervor.

I have never before encountered such a coarsely chopped brisket for a barbecue sandwich. This one had chunks of still-barked beef upon it, the rind edge of the brisket, one-half inch thick in places. That is not to say this made the quality poorer; in fact, I was thrilled to be able to sink my teeth into brisket that resembled what came from my own kitchen, thick with hickory smoke and a touch of rosemary. It was a sandwich that made you feel like you’d actually involved yourself in the eating of it rather than just letting something soft slide down your throat. The slaw was the perfect accompaniment, a little creamy with big chunks of white-ish cabbage laid in a circle under the bun.

So it was at eight o’clock on a Friday evening that we each found the perfect meal awaiting us at this comfortable brown-clad building alongside the main drag south of downtown Newport.

So what happened to Lackey’s? Why did the restaurant disappear, and how did those tamales come to be on the Smokehouse BBQ menu? It all goes back to Clint Lackey. Now, Clint didn’t actually come up with the recipe for the tamales—that recipe came from a street vendor in town eons ago—but he did produce them and the name stuck. It used to be that you could get them at Lackey’s restaurant and through the factory at Tuckermann, which sent tamales out to be sold in stores hither and thither. The factory burned in 2012.

Along the way, Clint Lackey struck up a business with Scott Whitmire, and the two ran both the Lackey’s restaurant and Smokehouse BBQ before getting to run both was too much. Clint ended up giving the business to Scott, and he’s run it since. The old Lackey’s is now a bar on the other side of town, and the Smokehouse keeps the tradition and recipes going. You can’t get Lackey’s in the grocery store, but you can still pick up frozen ones at Smokehouse to take home.

A pot full of Pasquale’s Tamales in their “juice.” Grav Weldon.

Most folks in Helena–West Helena know the Burger Shack by its motto, “Best Coke in Town.” Grav Weldon.

Pulled pork and bottled sauce at Jones’ Barbecue Diner, Marianna. Grav Weldon.

A strawberry sundae at the Mammoth Orange Café in Redfield. Kat Robinson.

Couch’s Corner closed a few years ago, but two other family-run locations still endure in Paragould and Trumann. Grav Weldon.

Presley’s Drive In in Jonesboro makes one mean Reuben sandwich. Kat Robinson.

This thirty-three-ounce porterhouse steak with sides at Taylor’s Steakhouse in Dumas was meant for two. Grav Weldon.

Sue’s Kitchen in Jonesboro is a good place for not only burgers and fries but crab cakes as well. Grav Weldon.

Chicken gizzards are one of the many local favorites offered at Walker’s Dairy Freeze in Marked Tree. Grav Weldon.

Shadden’s Bar-B-Q in Marvell still appears ready to open, though its proprietor died years ago. Grav Weldon.

Barbecue sandwiches, like this one at Kibb’s Bar-B-Q #2 in Stuttgart, are usually offered with coleslaw under the bun. Kat Robinson.

A hamburger at Bonnie’s Café in Watson. Kat Robinson.

The catfish sandwich at Gene’s Barbecue in Brinkley. Kat Robinson.

The Triangle Café in Batesville is popular with the local crowd who come for lunches and for breakfast favorites, like these pancakes. Kat Robinson.

The Roast Prime of Beef at Colonial Steakhouse in Pine Bluff is known for being a two-meal steak. Kat Robinson.

The Four Star Salad at Elizabeth’s in Batesville includes tuna, shrimp, chicken and pasta salads with pickled okra. Kat Robinson.

The Front Page Café in Jonesboro. Grav Weldon.

This Double Hutt Burger at the Sno-White Grill in Pine Bluff is named for the Hutt Building Material Company a few blocks away. Kat Robinson.

Deviled eggs are one of the options for salad at the Country Kitchen restaurant in Pine Bluff. Kat Robinson.

Diners at the Parachute Inn in Walnut Ridge can consume their repast within the fuselage of a Southwest Airlines passenger jet. Grav Weldon.

The seasonally offered strawberry shortcake at the Bulldog Drive In in Bald Knob has become famous. Some individuals travel from out of state to enjoy the old-fashioned dessert. Kat Robinson.

The Chicken Special at Parkview Restaurant in Corning is an entire chicken dismembered, battered and deep fried, served with roasted potatoes. Grav Weldon.

Batten’s Bakery in Paragould offers dozens of different pastries, such as these fried honeybuns. Grav Weldon.

Taco Rio’s famed Taco Burger includes everything you get inside a taco on a hamburger bun. Cheese sauce or chili is extra and popular. Grav Weldon.

The distinctive flavor of the burgers and steaks offered at Jerry’s Steakhouse in Trumann come from a custom-made flaming grill. Grav Weldon.

Chef Joe Cartwright’s interpretation of a Delta classic: roasted herbed catfish, root vegetables and coleslaw. He works with fresh local meats and produce at the Wilson Café in Wilson. Kat Robinson.

Lasagna, made from old Marconi family recipes, at Uncle John’s in Crawfordsville. Kat Robinson.

Like many Delta restaurants, Cotham’s Mercantile in Scott offers daily lunch specials, such as the meatloaf seen here. Kat Robinson.

Coconut meringue pies, fresh out of the oven, cool on the counter at Charlotte’s Eats and Sweets in Keo. Kat Robinson.

Pie is the default dessert served with barbecue around the Arkansas Delta, like this fried coconut pie with the smoked half chicken dinner at Demo’s Smokehouse in Jonesboro. Kat Robinson.

Mexico Chiquito founder Blackie Donnelly created cheese dip in Arkansas in the 1940s. This example from Smokehouse BBQ in Newport contains Cajun spices and pulled pork. Grav Weldon.

Bread pudding is a popular dessert at sit-down restaurants in the Delta. This delectable version is the only dessert on the menu at Murry’s Restaurant near Hazen. Kat Robinson.

A crawfish boil is one of the many options offered on the buffet at Dondie’s White River Princess in Des Arc. Grav Weldon.

Fried green tomatoes, a southern classic, are a popular side dish. This marvelous example comes from Colby’s Café and Catering in Wynne. Kat Robinson.

Homemade sauces, like the asiago cream sauce on this dish of chicken cannelloni, are part of the allure at Lazzari Italian Oven in Jonesboro. Grav Weldon.

THE HUNGRY MAN RESTAURANT, NEWPORT

Out of the ashes of one great Arkansas restaurant chain came Newport’s best burger joint. The chain in question was Wes Hall’s indomitable Minute Man. From its roots in 1948, the Minute Man became the burger palace of choice for many Arkansas communities. The chain’s innovations changed the face of what we know now as fast food, starting with the introduction of the Radar Range Pie, co-operative marketing giveaways like free Coca-Cola glasses with purchase, the Magic Meal (the first kids meal, two years before McDonald’s created the Happy Meal) and even a burger with special sauce (before the Big Mac).

The Hungry Man Restaurant in Newport. Grav Weldon.

But when the franchise died in the 1980s, some locations managed to keep going. Today there’s just one Minute Man left (in El Dorado), and in Newport, the chain’s heir is the Hungry Man. Started in 1977, by Carroll and Jeanette Wilson, it’s still a charbroiling hub for northeast Arkansas.

The Wilsons already owned three grocery stores (one in Newport, two in nearby Tuckermann) when they bought into Minute Man. They thought it would be easy to run. It was anything but. Jeanette managed the restaurant and kept it going. They sold off the grocery stores in 2001.

Once the name was changed and the last vestiges of Minute Man were gone, the Wilsons turned the menu into their own, adding flame-broiled steaks and smoked meats to their repertoire. They even added a signature sandwich called the Three Little Pigs—smoked pork, smoked sausage and bacon on a bun. It’s still one of the only places you can get a bona fide original Hickory Burger.

Of all things, the restaurant’s become very well known for its cakes. Baked fresh daily, slices line the counter in clear plastic boxes—red velvet, peanut butter, chocolate, strawberry and Italian cream. If you drop by, you have to take some cake home with you.

Raw Apple Cake

Speaking of cakes, my friend Susan Harrington shares this recipe for a raw apple cake.

“My grandmother’s name was Inez Golden and was known to most of her grandchildren as Mama Golden,” she told me. “She lived most of her life on a farm just outside of Greenway Arkansas and was an amazing cook. She raised five children and had twelve grandchildren.”

1 cup sugar

1 stick (½ cup) butter

1 egg

1½ cups all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon baking soda

1¼ teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon vanilla

½ cup black coffee, brewed

2 cups apples, peeled and chopped

Topping:

¼ cup sugar

½ cup coconut flakes

½ cup chopped walnuts or pecans

Note: Throughout the recipe, do as little mixing as possible, combing ingredients just until blended.

Heat oven to 350 degrees. Prepare a 9 × 13 cake pan. Beat together sugar and butter; add the egg. Mix together flour, salt and baking soda; slowly add to sugar mixture. Add vanilla and coffee and mix. Fold in the apples by hand. Mix together sugar, coconut flakes and chopped nuts and sprinkle on top. Bake for 30 minutes, checking after 20 to 25 minutes. Serves 8.

HOXIE

Up the road from Newport, the next spot of civilization is actually two cities. Hoxie and Walnut Ridge sit right next to each other and share a total population of about eight thousand people. But why aren’t they just one town? It has to do with the railroad. Back in the 1870s, Walnut Ridge wanted the Kansas City, Springfield and Memphis Railroad to come through town, but no one could agree where the tracks should lay or the depot be built. The city itself couldn’t purchase enough contiguous land to build a terminal. However, there was a lady who lived right south of town who was willing to make it happen. Mary Boas approached railroad officials and suggested that the railroad use her land, allowing it the right of way for no charge. Well, of course that was going to work. Boas and her husband, Henry, built a hotel near those tracks, and in 1888, Lawrence County accepted a petition to incorporate the town of Hoxie—which, incidentally, is named for railroad executive H.M. Hoxie of the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railroad.

Hoxie is probably best known for school integration. In 1955, the Hoxie School District became the third in the state (after Fayetteville and Charleston) to integrate its school in compliance with the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ruling. It was going so smoothly that Life magazine sent a reporter to cover opening day on July 11, 1955, an unremarkably quiet day. However, after a photo essay about the event went to press, more than three hundred local segregationists poured into town to protest, announcing a boycott of schools by white students.

Ten days later, members of the Little Rock chapter of White America attended a segregation rally in Hoxie, at which a petition listing one thousand signatures was presented, demanding the resignation of the entire Hoxie school board. You read that right—the Little Rock chapter came to town to oust the Hoxie School Board. Well, of course those board members stayed right where they were, and then-governor Orval Faubus soon announced that the state wasn’t going to intervene. Fed up with harassment from segregationists, the school board eventually filed suit against them. That suit was settled on October 25, 1956, when the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the Hoxie School Board.

Most folks don’t hear about the peaceful integration at Hoxie, though, because of the events of 1957 at Central High School in Little Rock.

THE PIZZA DEN

Hoxie is home to the Pizza Den, which first opened in 1989. Cliff Kinzer had worked for years in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, operating several restaurants and a wholesale supply warehouse. He and his wife retired young and moved to Ravenden, where the family raised cows. The restaurant bug was still with Cliff and the Pizza Den soon followed. Today, Cliff’s daughters Tonya Stacy and Gobbie Milgrim, along with Gobbie’s husband, Jonathan, keep the place running.

“We do make our own dough for the pizzas, po’ boys and all the bread,” Gobbie Milgrim told me. “We also slow cook our own roast and make our own chocolate chips cookies from scratch. Some of our more popular items are our pepper steak po’ boys made from our slow-cooked roast and our cookie dough pizza made with our chocolate chip cookie dough.”

The Pizza Den in Hoxie. Grav Weldon.

Robert “Washboard Sam” Brown was born in Walnut Ridge in 1910. One of the early pioneers of the blues and purported half-brother of blues musician Big Bill Broonzy, he moved first to Memphis and then to Chicago, where he recorded more than 160 tracks. Unable to make the transition from acoustic to electric blues, he retired from music in 1949 and became a Chicago police officer. Brown died in 1966.

But they make a lot more there, including fried chicken, catfish and pasta. The restaurant is also one of the very few places in the state where you’ll find beignets on the menu.

Hoxie itself has fewer than three thousand residents, and for them, the Pizza Den is part of the community. Milgrim told me about a pregnant lady who went into labor but came by to get a pepper steak before heading into the hospital. And then there was the time the building next door caught fire: “A family had to drive their little girl by the restaurant at midnight to show her the Pizza Den hadn’t burned down so she could get to sleep. She was so worried.”

The Pizza Den’s not going anywhere. You’ll spot it alongside U.S. Highway 67 opposite the railroad tracks. It’s hard to miss the prominent stone construction. “My sister and I have grown up with our customers. They are like family,” Gobbie confirmed.

WALNUT RIDGE

Walnut Ridge was actually settled along the first low ridge of the Ozarks to the west of the current town in 1860. Word that the railroad was going to pass through the plain to the east got around, and a little more than ten years later most of the town had moved to its current location. Colonel Willis Miles Ponder, a Civil War veteran from Missouri, formally founded the town of Walnut Ridge in 1875 and became its first mayor. Incidentally, Walnut Ridge’s move set it right atop an existing community called Pawpaw (named for all the pawpaw trees in the area). Today, the city of Walnut Ridge isn’t even on a ridge, and now you know why.

The city may have lost the railroad, but it gained an airport. During World War II, an air force flying school was located north of town. Pilots were trained on BT-13s there. In 1944, the air force traded the facility to the Marine Corps. Once the war ended, it became a storage depot and dismantling base. At one point there were more than ten thousand planes held there, the largest number of aircraft ever amassed at one place. Williams Baptist College, which had started up in Pocahontas in 1941, moved into part of the facility in 1946. These are still not the biggest events that happened at that airport.

POLAR FREEZE, WALNUT RIDGE

Jack Allison has it made. Every day he wants to, he goes in to work at a restaurant he founded in 1958. He gets to sit down with his friends, who come by for coffee or a morning milkshake, and chew the fat with them. He smokes hams and makes burgers and when he wants to take off for a day or a week, he can do that.

Allison’s place is the Polar Freeze in Walnut Ridge. Fifty-six years ago he started up the drive-in along U.S. Highway 67, and through the years his three kids and his wife have helped him out. The kids ended up going off to college and starting families of their own, and his wife eventually retired from the business three years ago. But Allison keeps on going.

The Polar Freeze is an institution around town. The oldest restaurant there, it still offers carhop service and a place to sit down and enjoy your meal indoors. Unlike other drive-in restaurants, there’s far more than burgers and fries on the menu. There’s also barbecued ham.

Jack Allison’s Polar Freeze in Walnut Ridge. Grav Weldon.

“I barbecue fresh hams,” Allison states, “that’s all I’ve ever barbecued. Most people barbecue Boston butts or shoulders, maybe because they are cheaper, but they are a little greasier from my experience. I like fresh hams and I have a batch cooking right now that’s going to come off in a couple, three hours.”

I’d interrupted Allison twice this morning, first when he had been talking with a family and their little girl and again now, when his buddies were having their coffee fix. But he was affable and once I got him talking, he just kept on rolling:

I bought it on the first of July 1958 and have been here on this corner all these years. I have a manager that’s been with me about thirty-five years, an assistant manager twenty-five years, and when I really want to do something I just plan it and go do it!

Walnut Ridge is a little old town. We have about four thousand population here, and everybody’s been real good to me. I’ve had pretty good business all these years. I couldn’t have had a better life. I just enjoy it mainly because I get to see all my friends. They’re good friends, but they’re not going to knock on your front door when you’re retired. They will come by and get coffee or a milk shake and talk. If I have a day off with nothing to do I’m just bored.

I had to ask him about the crazy day that the town has recently received a lot of notice for. On September 18, 1964, a particular musical group had a stopover in the town and Jack Allison is the man credited with the discovery. He laughed when I asked.

They give me credit for it, but I really don’t deserve the credit. I was picking up paper and trash off the lot at maybe ten, eleven o’clock at night and I saw this large plane circling. We have a wonderful airport at Walnut Ridge—I thought it was unusual to see it come through the night. About that time, three teenagers came running around in a car. I asked them what they were doing and they said “trying to run around” so I told them to go check on the airport and see what was going on with that plane, and here they went.

An hour later they came back all excited. They said it was the Beatles. Now, I said, “Don’t come back into town starting some sort of rumor like that.” “No, Jack, that’s the Beatles,” they said. I didn’t believe it. Because I was stationed in England for thirty months and I was twenty miles from Liverpool and that’s where the Beatles started. And it was a coincidence, it really was the Beatles—so that’s the story there. What I did, I did completely just to give those kids something to do.

At the time of this writing, Allison was eighty years old. Before we ended our conversation, I told him to have a good day. “At eighty years old, every day’s a good day,” he chuckled.

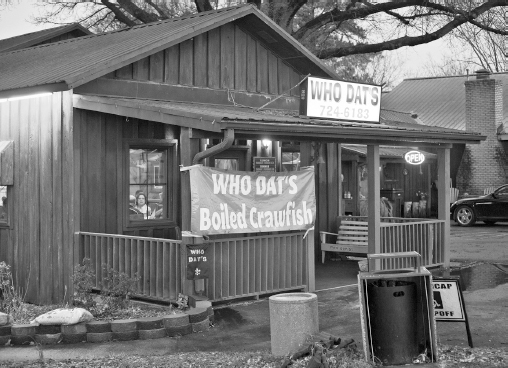

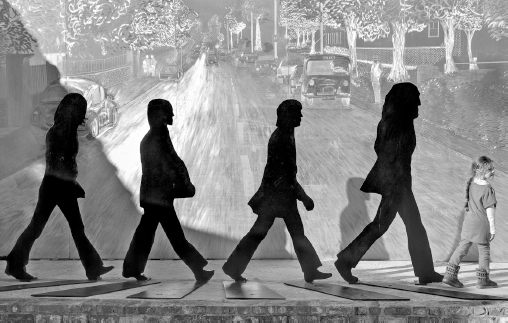

THE BEATLES AT WALNUT RIDGE

The Beatles had indeed come through that night, to change planes and head on for a day’s rest at Reed Pigman’s ranch up in Alton, Missouri. Word spread quickly about their visit, and on the rumor of a return through the airport, nearly three hundred people skipped church that Sunday morning and were onhand when the plane returned September 20. People took photos with the plane waiting to transport the famed musicians to their next destination. Family movies were shot, and teenagers sang Beatles songs. Sure enough, a plane carrying John Lennon and Ringo Starr landed that morning.

At the Walnut Ridge depot, you’ll find the Guitar Walk. The 115-foot-long by 40-foot-wide concrete depiction of an Epiphone guitar is accompanied by interpretive panels celebrating the great musicians of Rock ’N’ Roll Highway 67, including Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, Roy Orbison, Conway Twitty, Sonny Burgess, Billy Lee Riley, Wanda Jackson and Elvis Presley.

What the crowd didn’t know was that Paul McCartney and George Harrison had already come to Walnut Ridge in an old pickup truck. They joined their colleagues, walked a gauntlet of thrilled fans and boarded the plane. The whole incident didn’t take long, but it left a permanent memory on the town.

Today, you can walk Abbey Road in Walnut Ridge. There, you’ll find a yellow submarine. Businesses all over town embrace the Beatles tie. In 2010, an artist by the name of Danny White created a sculpture that’s become a landmark: silhouettes of the Fab Four against a shiny sculpted wall. Yes, you can have your photo taken with the silhouettes of the Beatles, and each September, the city commemorates that little stopover with the Beatles at the Ridge Music Festival. Learn more at beatlesattheridge.com.

Beatles Park in Walnut Ridge. Grav Weldon.

THE PARACHUTE INN, WALNUT RIDGE

The Walnut Ridge Regional Airport is worth a visit, not just for its Beatles connection or for the neat air museum that commemorates its role in World War II or the planes that came to the facility afterward, but for its restaurant.

At that very same airfield where the Beatles came through in 1964 sits a strange little eatery. Strange, that is, not for the food but for the fact that its main dining room is the fuselage of a Boeing 737 passenger jet. The place is the Parachute Inn.

The restaurant’s new fuselage has just been added to an older restaurant that served the community since 1968. Harold and Janie Johnson ran the little diner next to the airstrip over all those years. But in 2004, new owner Donna Roberts bought the majority of an old Southwest Airlines jet and started the conversion, which included laying the plane on its belly and building a connecting staircase and hangar. Rhonda Higginbotham purchased the property in 2008.

Inside the Parachute Inn’s dining room, the fuselage of a Southwest Airlines passenger jet. Note the signatures on the overhead compartments. Grav Weldon.

Today, you have a choice when you go in—settling for sitting close to the buffet line inside the original restaurant building, or going up the steps and choosing a spot along the ninety-two-foot open area of the plane. Kids often take over the cockpit, which is full of dials and levers and overhead details like you’d find in any jet. Some of the main body’s seats have been removed for tables; other seats have been reversed to face the same way, just like a booth in a restaurant. Overhead, the old luggage compartments bear the signatures of hundreds of Southwest Airline employees who have made the journey to Walnut Ridge just to dine in the old aircraft.

The gimmick of dining in the jet isn’t the only draw. The restaurant has become well known for serving up spicy catfish, chicken livers and other local classics alongside burgers and fries. Dessert is always homemade, and the chocolate cake must come from the same recipe my ancestors utilized, complete with chocolate icing—not frosting—on top.

POCAHONTAS AND CORNING

U.S. Highway 67 shoots due north from Walnut Ridge to collide with the edge of the Ozarks in Pocahontas. The oldest soda fountain in the state, Futrell Pharmacy, is located on that ridge downtown—on the edge of the Arkansas Ozarks (its story is included in Classic Eateries of the Ozarks and Arkansas River Valley). Indeed, the Delta arguably begins just two blocks away, on the banks of the Black River.

Pocahontas is one of the oldest towns in Arkansas. The first post office founded in the state back in 1817 was in Davidsonville, a few miles to the west. Originally called Bettis’ Bluff, Pocahontas was incorporated and received its permanent name in 1835. It serves as the Randolph County seat and retains its 1872 Italianate courthouse. Randolph County is the only county in Arkansas crossed by five different rivers.

U.S. Highway 67 darts east to Corning. This little town close to the state’s northern border used to be a popular stop for travelers. Originally named Hecht City and centered around Levi and Solomon Hecht’s lumber mill on the Black River, the town moved west to take advantage of the new Cairo and Fulton Railroad that ran through Clay County. It was named for H.D. Corning, a rail engineer, in 1873. Apparently the way to have a city named after you in the nineteenth century was to work for a railroad!

PARKVIEW RESTAURANT, CORNING

Corning is one of two county seats for Clay County (the other being Piggott to the east). It benefits from being the first town with any sort of facilities on the south side of the Missouri border. For many years, several hotels operated there for travelers coming into the state. Of them, the Parkview has kept a strong clientele through the years. Originally the Parkview Tourist Court and later Rusty’s Parkview Motel and Restaurant, the facility is commemorated in a series of postcards issued over the decades. One reads:

Offering all conveniences to the traveling public. Twenty-eight rooms, tile baths, air-conditioning, telephone in every room, controlled heat, free television, Simmons Beauty Rest mattresses, free swimming pool. Beautiful city park adjoining for your pleasure. Restaurant and auto services next to motel. A really delightful place to stop.

Today, the Parkview Restaurant serves as community center for generations of town residents. Barely changed from the 1950s, it serves steaks, catfish and fried chicken. Its ancient tables and booths offer a respite from travel and a good, hearty meal.

East of Corning on U.S. Highway 62, you’ll come to the town of Piggott, about as far northeast as you can get in the state. While the village’s classic eateries have all disappeared, it’s worth a visit to the Arkansas home of Ernest Hemingway. The famed author lived with wife Pauline Pfeiffer in her parent’s home for a few years. Today, you can tour the home and visit the barn loft where Hemingway wrote most of A Farewell to Arms. Learn more about Hemingway’s Arkansas years in Dr. Ruth Hawkins’s book, Unbelievable Happiness and Final Sorrow.

There’s a special you should consider when you’re dining there. The Chicken Special is $10.99 and includes a whole fried chicken. No, not all together—it’s actually cut into pieces, battered and fried while you wait. It takes about twenty-five minutes from the moment you order to when it arrives at the table, and it comes with grill-roasted potato halves. And it’s worth every nickel and every minute and every bite.

Like most good Delta restaurants, it has pie—in this case a coconut cream pie that’s just divine, made from scratch from the crust up.