PART I

A FRONTIER PORT BECOMES A CITY

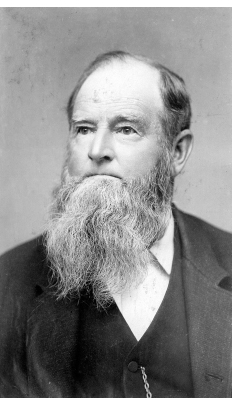

THE HORTON HOUSE

The great need of this town is about to be supplied by A.E. Horton, Esq., who will immediately erect, on the northwest corner of Fourth and D Streets, a palatial brick edifice, for hotel purposes. It is to contain a hundred rooms and to be fitted up with elegant furniture and all modern improvements.

–San Diego Bulletin, December 18, 1869

San Diego in 1869 was on the verge of a boom. A railroad connection to the east, which would make San Diego the terminus of the first transcontinental railroad, seemed likely. Anticipating the link, real estate sales boomed. The Bulletin declared, “From a place of no importance, the home of a squirrel a few months back, we now have a city of three thousand inhabitants.”

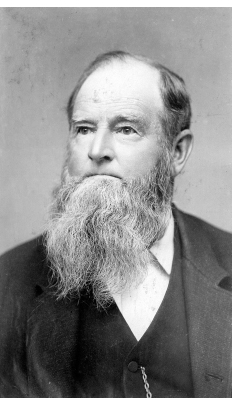

Only two years earlier, a businessman from San Francisco, Alonzo Erastus Horton, had started it all by buying San Diego pueblo land near the port—not far from the failed town site of William H. Davis, whose 1850s venture was already known as “Davis’ Folly.” Horton succeeded by selling off lots of “Horton’s Addition” at bargain prices to attract settlers and businesses. For many investors, the impending arrival of the railroad clinched the deal.

On New Year’s Day 1870, Horton broke ground for a first-class hotel that would be the centerpiece of the rising city. A shipload of rough lumber was “promiscuously dumped” around a brush-covered site on D Street, and “nearly all” the carpenters and bricklayers in town set to work. Horton’s brother-in-law, W.W. Bowers, supervised the construction of the hotel, working from a crude sketch of San Francisco’s famed Russ House as a model. The two-and-a-half-story, one-hundred-room hotel was finished in only nine months at the cost of $150,000.

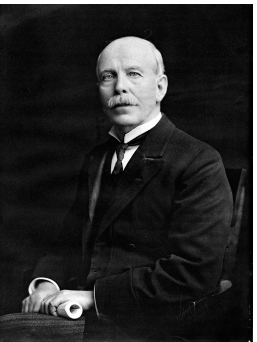

Alonzo Erastus Horton, builder of the Horton House. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

The Horton House opened on October 10, 1870, to rave public reviews. Calling itself “the largest and finest hotel in California south of San Francisco,” it featured gas lighting and rich carpeting throughout the building, rooms with steam heaters and marble washstands filled with “pure soft water” conveyed by pipes (from a well) and bathrooms running both hot and cold water. Perhaps the hotel’s proudest achievement was “an electrical bell apparatus, with wires,” which ran to the office from every room.

The hotel soon operated at capacity and brought new business to San Diego. Hotel guests paid $2.50 for a room, meals included. The San Diego Union noted that “Horton has met the great need of our young city. He did it by building and keeping a first class hotel…the Horton House has done more for San Diego than all other improvements combined.”

Horton kept the ownership of the hotel for several years, but only with difficulty. In 1873, the railroad syndicate that had promised a terminus in San Diego collapsed. San Diego’s boom faltered, and Horton found himself in financial trouble. He leased the Horton House and looked, unsuccessfully, for a buyer of the hotel. He also borrowed money, using his hotel as collateral. When Horton defaulted on a loan from a local businessman, he almost lost the property.

San Diego’s Horton House, the “finest hotel in California south of San Francisco,” opened in October 1870. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

In M.S. Patrick v. A.E. Horton, it was alleged that $4,107 was owed to Mr. Patrick. To satisfy the debt, the district court issued a writ of attachment that demanded that Horton surrender all the furnishings of the hotel. Horton survived the crisis, but the court case file, which contained a room-by-room inventory of the Horton House, provided lavish evidence of the “best style” for which the hotel was known.

The attachment papers listed the contents of every room: hotel office, sleeping rooms, bar, library, billiard room and dining room. The most minimal bedroom contained a bedstead with sheets, pillows and blankets, as well as towel racks, chamber pot, spittoon and chair. More sumptuous quarters added loungers and rocking chairs. Some rooms boasted pianos, marble center tables and oil paintings on walls. The hotel bar was well stocked with nearly one hundred varieties of liquor and several thousand cigars.

For several more years, Horton leased out the hotel while he struggled with mortgage payments, but foreclosure loomed. Finally, in August 1881, the Union politely reported, “We take pleasure in announcing that the Horton House has passed into the hands of W.E. Hadley, who took charge yesterday evening.”

William Hadley would run the Horton House for the next two decades, occasionally making renovations and small additions. In March 1886, the hotel boasted the “first private electric light in the city.” As the hotel’s premier status was gradually eclipsed by newer hostelries, Hadley promoted his “moderate” prices with “special rates to families.”

On August 12, 1895, a headline in the San Diego Union blared, “Horton House Is Sold.” The buyer was the family of U.S. Grant Jr., who paid $52,251 for the property. “It is understood,” the newspaper reported, that Grant will eventually build “a grand hotel building” on the site of the Horton House.

Years of rumors followed about a possible new hotel. In 1903, the Union reported that architects Hebbard and Gill had drawn preliminary plans for the site. The plans were never used. More time would pass before U.S. Grant Jr. decided to tear down the Horton House and build a new hotel as a monument to his father, President Grant.

On July 12, 1905, a large crowd watched as Alonzo Horton, age ninety-one, ceremoniously removed a brick from the hotel he had built thirty-five year earlier. Turning to the crowd, Horton said that it was his wish that the brick be used “in the principal wall of the new structure.”

Construction of the new hotel, designed by Harrison Albright, began but then stopped, delayed by the San Francisco earthquake and funding difficulties. Five more years would go by before the U.S. Grant Hotel officially opened on October 15, 1910.

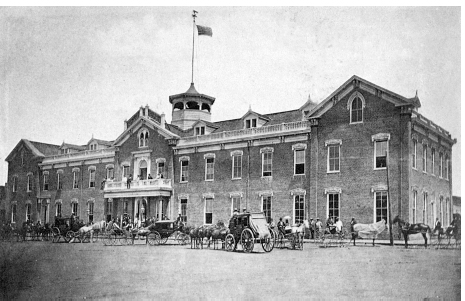

CABLE CARS IN SAN DIEGO

One of the great needs of San Diego for some time past has been a system of cable street railroads. This improved method of covering long distances in cities has become very popular in all of the metropolises of the country, and it has been one great improvement in which San Diego was deficient.

–San Diego Union, June 9, 1889

Urban public transportation in the late 1800s meant streetcars—not the “time-honored horse car” or experimental electric lines but “grip cars,” pulled smoothly through city streets by a continuous iron cable. San Francisco mastered the cable technology in the 1870s. Other growing West Coast cities followed: Seattle, Portland, Oakland and Los Angeles.

In the summer of 1889, San Diegans eagerly waited for the construction of their own modern cable car railway. Investors, led by bankers D.D. Dare and J.W. Collins, pooled their money for startup costs. “Within one year,” prophesied the Union, streetcars would cover “the main business portion of the city, passing by some of the finest suburban residences here, and giving direct and easy communication with the heart of the city…The citizen residing on University Heights will be whirled down to his place of business by a commodious car, propelled by a steam cable.”

The San Diego Cable Railway Company was incorporated in July 1889. Dare and Collins were elected president and treasurer, respectively. City Alderman John C. Fisher was vice-president and general manager. The chief engineer, tasked with building the railway, was Frank Van Vleck, who had gained experience working on the Los Angeles Cable Railroad.

Van Vleck planned a five-mile route that ran from the foot of Sixth Street to C, then up the hill on Fourth Street to University Avenue, where it turned east for several blocks before continuing north on what became Park Boulevard and Adams Avenue, ending at the “Bluffs” over Mission Valley. The route was designed to take advantage of potential real estate sales in the barren, undeveloped stretches along upper Sixth and the heights above Mission Valley.

“Dirt flew” in August when a crew of two hundred men began excavating the four-foot-wide trench that would hold the tracks and cable. The steel rails, weighing thirty pounds per yard, rested on an iron frame, or “yoke,” set in concrete. The 1 -inch, iron-strand cable ran through an underground conduit centered between the tracks. As the line neared completion, a team of twenty horses pulled fifty thousand feet of cable through the conduit.

-inch, iron-strand cable ran through an underground conduit centered between the tracks. As the line neared completion, a team of twenty horses pulled fifty thousand feet of cable through the conduit.

To save money, the line was built as a single-track, meaning cable cars moved north and south on the same rails. Sidings allowed cars to pass in opposite directions, and turntables at the ends of the line let the cars turn around. A power plant at Fourth and Spruce generated the steam to turn massive winding wheels for pulling the cable.

After “innumerable and vexatious delays,” the railway opened on June 7, 1890. A day of congratulatory speeches and festivities heralded the inauguration. Governor Robert Waterman and other dignitaries took rides in streetcars decorated with flags and flowers. Renowned horticulturist Kate Sessions was said to be the first paying passenger.

The streetcar line ran with twelve “combination” cars—one half closed and the other open—similar to San Francisco’s Powell Street cable cars. San Diego’s “gorgeous palaces on wheels”—built in Stockton and shipped to San Diego—boasted stained-glass clerestory windows, coal-oil lighting and surfaces of nickel-plate and hardwood. A novel innovation was electric stop-bells powered by batteries beneath the seats. Cars were named—not numbered—to highlight San Diego communities: “El Escondido,” “El Cajon,” “La Jolla,” “Point Loma” and “San Ysidora.”

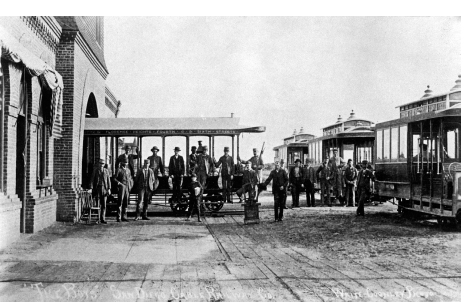

San Diego’s “gorgeous palaces on wheels” were named to highlight San Diego communities, such as “Las Penasquitas.” San Diego Electric Railway Association.

The cable car barn at Fourth and Spruce Streets. Southwest Railway Library, Pacific Southwest Railway Museum.

The attendants wore gray uniforms and caps, with gold buttons for the conductors and silver for the grip men. For pay of eighteen cents per hour, they alternated a “short day” of 5:30 a.m. to 3:15 p.m. with a “long day” of 5:30 a.m. to 11:00 p.m., with one hour off for lunch. The crews were responsible for buying their own uniforms (about twenty dollars) and cleaning their own streetcars.

The cable cars were popular, particularly on weekends. For a fare of one nickel, riders traveled at eight to ten miles per hour from downtown to uptown in University Heights in as little as ten minutes. Trailers were sometimes attached to the cars to accommodate large crowds. A popular attraction for families was the Bluffs on the northern end of the line. Later known as Mission Cliff Gardens, the park featured six acres of terraced walks and gardens on the canyon rim overlooking Mission Valley. There were band concerts, dances and traveling shows from a pavilion stage.

But for all its popularity, the system lost money for the Cable Railway Company. Installation of the line had been costly, and ongoing operating costs strained the cash flow. Brakes needed servicing weekly, and the cable grips had to be replaced every three weeks. The company was also forced to pay for expensive street paving in roadways that were only dirt when the tracks were laid.

A banking scandal precipitated the end. In November 1891, the California National Bank closed its doors. The bank’s president, J.W. Collins, was arrested for embezzlement, while D.D. Dare fled to Europe. The two men had been principal backers of the cable railway, and with their bank gone, the company went into receivership.

For the next several months, court-appointed receivers managed the railway, which limped along, running fewer cars to save money. A broken cable closed a portion of the line in late summer. New cable was ordered, but with no money to install it, the company chose to shut down forever on October 15, 1892.

THE CARNEGIE LIBRARY

If the city were to pledge itself to maintain a free public library from taxes, say to the extent of the amount you name, of between five and six thousand dollars a year, and provide a site, I shall be glad to give you $50,000 to erect a suitable library building.

–Andrew Carnegie, July 7, 1899

Between 1883 and 1929, the industrialist turned philanthropist Andrew Carnegie funded construction of 1,689 libraries in the United States. San Diego had the honor of being the first Carnegie library in California.

Since its founding in 1882, the San Diego Public Library struggled to find adequate funding and a permanent home. Rented floors in a bank building at Fifth and G Streets served the book collection for its first decade. Cost-cutting forced a move in 1893 to rooms in the St. James Building at Seventh and F Streets. Another move came in 1898 to the fifth floor of the Keating Building at Fifth and F. With only meager financial support from the city, a permanent home for the library seemed unlikely.

Lydia Knapp Horton lobbied philanthropist Andrew Carnegie for funding to build San Diego’s first library building. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

Library supporters were not discouraged. The Wednesday Club, an “artistic and literary culture” club of San Diego women, adopted the library as its special project. Led by Lydia Knapp Horton, the wife of San Diego founder Alonzo Horton, the women began a library building fund.

In October 1897, Lydia Horton wrote to Andrew Carnegie requesting pictures of library buildings he had sponsored. The philanthropist mailed a set of prints, which the Wednesday Club exhibited as a fundraiser. Mrs. Horton continued the correspondence, telling Carnegie in May 1899 that “the library needs of this place are very apparent…we feel more than ever the need of permanent quarters.” Carnegie responded with the offer of $50,000 to build “a suitable library building.”

Amid the excitement over Carnegie’s generous offer, the project immediately bogged down in debate over where to locate the new building. Several different downtown sites were promoted for the honor. The size of the property was also questioned; businessman George W. Marston argued strongly for a whole block and warned that “the city will regret for all time its error if it should let this opportunity pass without obtaining the full square of land for the library.”

After several months of public acrimony, a half-block tract of land was purchased at Eighth and E Streets for $17,000. The city paid only $9,000, with the remainder coming from private donations, including $1,000 from George Marston and $500 from the Wednesday Club.

Bids for the construction of the library were solicited in a national competition. The request for proposals called for a building “as nearly fireproof as possible,” using granite or brick construction. All rooms were to receive as much natural light as possible, “as all Californians recognize the necessity of sunny rooms.” The successful architects would receive 5 percent of the building budget as full compensation for their plans and specifications.

The design competition was won by Ackerman and Ross. The New York architectural firm had recently designed a Carnegie library in Washington, D.C. The San Diego architectural firm Hebbard and Gill was subcontracted by Ackerman and Ross as construction superintendents.

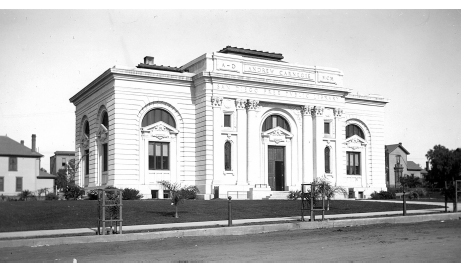

Construction for the library began in December 1900. Sixteen months later, on April 23, 1902, the library opened. The completed building was a beautiful, Classical Revival–style structure, built of brick and covered with white cement, giving a marble appearance to the exterior. The library was fronted by a grass lawn, with landscaping designed by horticulturist Kate Sessions and funded by George Marston.

Library historian Theodore Koch (A Book of Carnegie Libraries, 1917) described the library’s interior:

The delivery room [circulation desk] occupies the center of the first floor; opening from this, on the one side, are a children’s room and a women’s magazine room; on the other a men’s magazine room and a reference room. Behind the delivery room are the librarian’s and catalogers’ rooms, back of which are the stacks. The second story contains an art gallery, a lecture room with seating capacity of 100, a museum, trustees’ room, and two small rooms for special study. The light green tint of the walls throughout the building blends harmoniously with the color of the oak furniture.

San Diego’s Carnegie library opened at Eighth and E Streets in April 1902. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

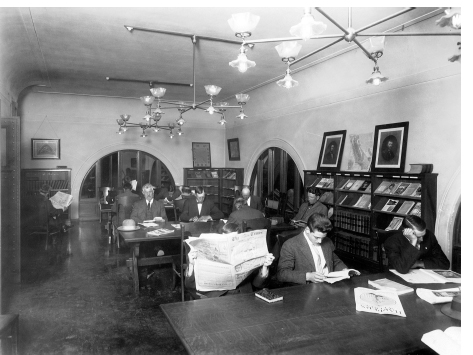

The men’s reading room in the Carnegie library. In the early 1900s, the sexes were segregated in most public libraries. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

With furnishings, the building had ultimately cost $60,000. The steel book stacks alone cost nearly $10,000. Fortunately, the Carnegie foundation agreed to increase its gift to cover the added costs, with the condition that the City of San Diego agree to support the library with at least $6,000 per year.

The new library reflected both new and old attitudes of public librarianship. Separate reading rooms for men and women were normal practice for the day. A central delivery desk for requested books was also a time-honored practice. But the library’s interest in service for children—apparent in the large children’s room—was quite modern. More revolutionary still was a willingness to allow patrons into the library stacks to choose books themselves, without a librarian’s help. In 1902, the San Diego Public Library was among the first public libraries to offer “open stacks.”

The size of the Carnegie building, designed for a city population of only 17,700 in 1900, seemed to shrink rapidly in just a few years. By 1910, the San Diego population had more than doubled in size, and the library had begun to suffer from crowding. In a few more years, shelving covered every available wall surface. Short-term relief came from moving several departments to rented spaces in nearby buildings. Remodeling the Carnegie in 1930 added more floor space, and the addition of new branch libraries took some pressure off.

However, the need for a larger library was clear. After failed bond measures in 1923 and 1937, the voters finally approved $2 million in bonds in 1949 to build a new main library and improve the growing branch library system. Three years later, the library moved into temporary quarters in an old exposition building in Balboa Park. The venerable Carnegie library, at age fifty, was demolished. The new Central Library, designed for a city population of less than 350,000, was built on the same site and dedicated on June 27, 1954.

THE SAN DIEGO BATHS

Salvation for the great unwashed is now offered in the waters of the Tropical Natatorium at the foot of D Street. This institution is thrown open to the public today. No pains have been spared for the comfort of the people.

–San Diego Union, November 27, 1886

There was a time in America when the standard for personal cleanliness was a weekly bath. The “great unwashed” often found that Saturday night soak in commercial bathhouses, such as the esteemed Tropical Natatorium, where bathers could indulge in warm, saltwater dips along the seashore. During San Diego’s population “boom of the eighties,” nearly a dozen bathhouses dotted the city’s waterfront.

San Diego’s first recorded bathhouse, Cotterel & White, opened in 1869 near Horton’s Wharf at the foot of Fifth Street. The first facility was a simple affair: a wire netting suspended alongside a barge formed a “swimming bath,” twelve by thirty feet. The barge provided dressing rooms and rental bathing suits.

Later bathhouses were fashioned from corrals of wooden stakes, pounded into the mud of the bay. The corrals sheltered the bathers from vagaries of the surf and also offered protection against the notorious stingrays of San Diego bay. The baths were open seasonally, usually from May until October.

Captain John Heerandner’s Caroline Bath House, at the foot of Sixth Street, was a popular success in the early 1880s. Heerandner drew evening crowds for his moonlight concerts featuring the San Diego Brass Band. The concerts were free. Bathers paid the usual fifteen cents. Heerandner also boasted a swimming coach from Sidney, Australia, who gave “instructions and exhibitions of his skill to all who so desire.”

Heerandner’s chief competitor was W.W. Collier, operating from the steamship wharf at the foot of Fifth Street. Collier claimed that his “accommodations for lady bathers [were] especially good” and featured large, floating tanks. The mornings were reserved for the women, as the Union announced: “Mrs. Collier gives her personal attention to lady bathers, and those who wish to learn to swim will have an excellent opportunity these warm sunny forenoons.”

Mrs. Collier’s lady bathers had a scare one day when their floating tanks nearly met disaster. “The cable at the steamship wharf bathhouse broke yesterday,” announced the Union. “The great tubs were about to go to sea while several ladies were indulging in the invigorating exercise of a swim. The cable was soon repaired, however, and the danger averted.”

Los Banos, at Broadway and Kettner Boulevard, was an architectural showcase designed by architects William S. Hebbard and Irving J. Gill. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

The Tropical Natatorium would easily eclipse the seasonal bathing corrals and floating tubs of Heerandner and Collier when it opened in November 1886 at the foot of D Street (today’s Broadway). Groundbreaking, for San Diego, was the two-hundred- by one-hundred-foot lined swimming bath, open to the bay. Seawater flowed through gates that opened and closed automatically with the tide. The facility boasted of electric lighting, steam-heated tub baths, Turkish steam rooms and an amphitheater. The giant pool featured “swings, slides, spring-boards and other things dear to the heart of the amateur athlete.”

In August 1897, the ultimate San Diego bath experience opened one block away from the Tropical Natatorium across the street from the Santa Fe depot. Los Banos was an architectural showcase. Built by Graham E. Babcock, the son of Coronado developer Elisha S. Babcock, the bathhouse was a red-tiled, Neo Moorish–style structure designed by the architects William S. Hebbard and Irving J. Gill.

Admission to Los Banos cost twenty-five cents, which gave the bather a swimsuit, a towel and a key to the locker room. The indoor concrete “plunge tank” was fifty by one hundred feet. “Pure seawater” filled the tank, heated by steam from the streetcar power plant on E Street, just behind Los Banos. “All the luxuries that a bather could desire, in the way of Turkish baths, plunges, showers, and slides” were provided, reported the Union.

Los Banos lasted for many years. But within that time, indoor plumbing was fast making inroads to American homes. Public bathhouses became passé. In 1928, the San Diego Gas and Electric Company tore down Los Banos and expanded the Station B power plant, which survives today at West Broadway and Kettner Boulevard.

SAN DIEGO STATE’S FIRST YEAR

We shall not wait until the new building on University Heights is finished before opening the normal school. We have decided to open it in temporary quarters on November 1, with a corps of perhaps five teachers.

–Wilfred R. Guy, Chairman, Board of Trustees, San Diego State Normal School

On November 1, 1898, the first classes of the future San Diego State University began. In leased rooms above a downtown novelty shop, eighty-one students appeared for the formal opening of the new San Diego State Normal School.

San Diegans had clamored for a state-funded teachers training college for years. Called “normal schools” because they instilled teaching norms, the institutions had already been established in San Jose, Los Angeles and Chico. Local boosters lobbied hard in Sacramento to secure a San Diego college—essential, they believed, for the growth of the region’s elementary and high schools.

Real estate promoters were also keen on securing a college that would anchor and encourage new development. A College of Arts and Sciences was proposed in 1887 for a new subdivision—optimistically called “University Heights.” As a branch of the University of Southern California, classes were held for a short time in a downtown church while construction started at Park Boulevard, but the college soon failed.

In 1894, school promoters got a second chance when sixteen acres of land and buildings in Pacific Beach were offered to the state by a developer in exchange for a school. With the proposed gift as an incentive, San Diego representatives secured state funding for a new normal school for the “training and educating of teachers.” The bill was signed by Governor James Budd on March 13, 1897.

Students wave from the top floor of the Hill Building at Sixth and F Streets in 1898. Special Collections, San Diego State University.

As part of the legislation, the school bill authorized a board of trustees that would select the permanent site for the school. Besides the original Pacific Beach offer, there were now competing choices. John D. Spreckels offered a site in his Spreckels Heights development above Old Town, and Escondido proposed the property and buildings of its own high school.

But the trustees were most impressed by University Heights at Park and El Cajon Boulevards. The site of the abortive College of Arts was the unanimous choice of the trustees on June 3, 1897. The firm Hebbard and Gill was selected to design and build the first buildings for a cost not to exceed $100,000. Ground was broken on August 1, 1898.

As Irving Gill’s classic Beaux Arts structure began to rise on Park Boulevard, the normal school trustees eagerly announced their intention to open the school as soon as possible in a temporary location yet to be found. Board chairman Wilfred Guy suggested it might be the Marshal-Higgins Block at Fourth and C Streets or possibly rooms at the YMCA at Sixth and D. Chairman Guy would only say, “We want to get the school in good running order as soon as possible and nothing stands in the way of accomplishing that objective.”

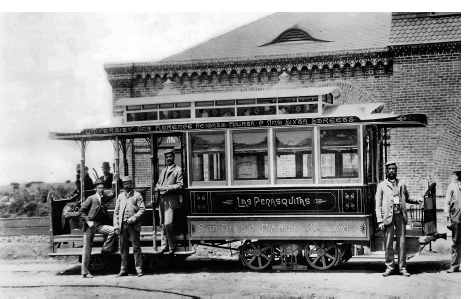

Samuel T. Black, a former state superintendent of public instruction, served as the first president of the San Diego Normal School. Special Collections, San Diego State University.

The trustees published notice in the newspapers inviting potential students to enroll at a downtown law office in the Keating Block for the two-year program. Applicants were expected to “be of good moral character” and have at least a grammar school education. They were required to file a declaration that they were entering the college “for the purpose of fitting themselves to teach” in public schools. The normal school would offer only three classes at first: English, algebra and history. The trustees apologized that a science class could not be offered owing to the lack of laboratory space and equipment.

First notice of a site came on October 8, only three weeks before the start of classes. The school’s new president, Samuel T. Black, the former state superintendent of public instruction, announced that he would establish his office in the Hill Block at Sixth and F Streets, where “the third floor and three rooms on the second floor will be fitted up for a temporary normal school.”

The school rooms were “fitted up in fine style,” according to the San Diego Union. “A notable feature will be the use of tables instead of desks for the students, and is President Black’s innovation.”

A faculty of five teachers was announced—all well-qualified, experienced instructors. Miss Emma Way accepted the lead job as preceptress, which paid an annual salary of $1,600. As “the moral instructor of the young ladies,” Miss Way was expected to dictate “what proper entertainments shall be attended” and also to designate a curfew time for the female students.

On the first day of classes, the students gathered in the assembly room and began their day with the singing of “America.” The invocation followed, delivered by Reverend A.E. Knapp. After addresses by President Black and Chairman Guy, the seventy-five young ladies and six young men were assigned rooms, and their studies began. Each day began in similar fashion: a gathering in the assembly room, where the students chanted the Lord’s Prayer and sang hymns. The teachers would then take turns reading from the scriptures before the students went to class.

Additional pupils were admitted in February “on account of the crowded conditions of the original classes.” With more than one hundred students enrolled, President Black judged the institution in “a very flourishing condition.” The lady students greeted the spring with the organization of a rowing club—the school’s first sports team.

San Diego State’s first year came to a close on June 29, 1899. With 135 students completing classes, the year had “far exceeded the expectations of everyone,” President Black declared. “While we have had only eight months’ school in which to do a full year’s work…work was accomplished in every line, but with one exception.” Algebra, the president noted regretfully, had not been finished “because the study requires more time than we could give it.”

In the fall of 1899, the San Diego State Normal School began the year at its permanent home on Park Boulevard. The school would graduate its first students that spring: twenty-three women and three men. In 1921, the growing school became the four-year San Diego State Teachers College, and in February 1931, the college moved to its current home on Montezuma Mesa in East San Diego.