PART II

CIVIC PRIDE

THE 1890 FEDERAL CENSUS

“I am incensed,” Mayor Douglas Gunn responded on Saturday when the census figure of 15,700 for San Diego was mentioned. “I shall write to the census authorities and the Secretary of Interior demanding a recount.”

–San Diego Union, July 7, 1890

The Eleventh U.S. Census officially began on June 2, 1890. In the next few weeks, forty-seven thousand census enumerators spread out across America to pore over town maps, knock on doors and personally visit every house and family in order to tally perhaps the most significant and controversial census the nation had ever seen.

Like most U.S. cities, San Diego looked forward to the decennial counting with optimism, knowing that it would show a major population rise and lead to significantly better legislative representation. Mayor Douglas Gunn estimated that the 1890 count would show a city population of at least 27,000, up from 2,637 in 1880.

A local clothing store, A. Dorsey & Company, displayed its census spirit by announcing prizes “to the best guesser” of the final count. First prize was the choice of any twenty-five-dollar men’s suit in the store. Second prize was an eight-dollar Dunlap silk hat, “the very best in the market.”

The questionnaire in the hands of San Diego’s sixteen enumerators contained twenty-five questions to be asked of every citizen. There was a separate sheet for every family. New entries in 1890 included questions about home ownership and indebtedness, and a query about race asked “whether white, black, mulatto, quadroon, octoroon, Chinese, Japanese, or Indian.”

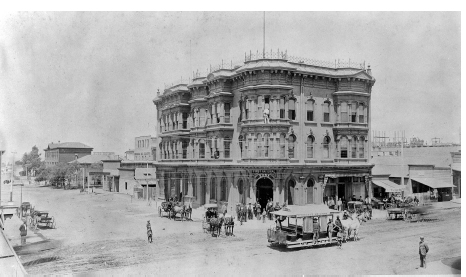

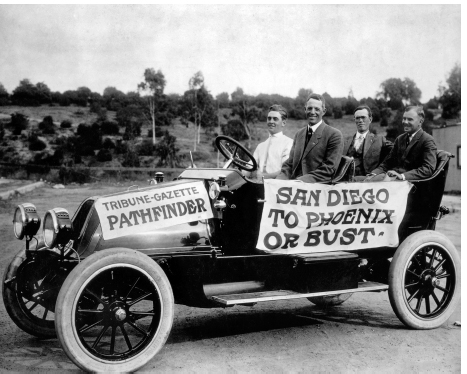

Fifth Street in the late 1880s showed unpaved streets, but a city was rising with new buildings, horse-drawn trolleys and a modern municipal government. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

There was little controversy over the questionnaire, but as the numbering got underway in San Diego, city officials quickly became concerned over the pace of the census taking and the completeness of the count. The Census Bureau required that cities of San Diego’s size be canvassed within two weeks. The count was particularly sluggish in the red-light district south of H Street, where shy residents tended to ignore the knock on the door.

Mayor Gunn moaned, “This enumeration is of too great importance to have it rushed…I have heard it asserted that the enumerators were going to make out a population something like 6,000 or more short of what it really is. If this is so, irreparable damage will be done to San Diego.”

As the enumeration neared its scheduled conclusion in mid-June, San Diegans began coming forward to announce they were uncounted. George B. Hensley, a businessman active in the chamber of commerce, declared that “none of his family had been seen by the census takers and he knew of many families who had been missed.” The proprietor of a local hotel complained that “her house was full of guests, none of whom had been counted.”

The chamber of commerce voiced its concerns by telegraphing a resolution to the superintendent of the census in Washington, D.C., conveying “earnest protest against the unsystematic, careless and inaccurate manner in which the enumeration of the population of this city is being made.”

Some people also refused to be counted. “The enumerators complain that they are rudely treated,” reported the Union. “One says he was ordered out of three places. As many doors were shut in his face, and eighteen persons positively declined to answer the questions.”

On June 19, the Union reported that people were being arrested for refusing to answer the census enumerator’s questions, per order of Census Supervisor L.E. Mosher from Los Angeles. A deputy U.S. marshal escorted three San Diegans on the train to Los Angeles who seemed “afflicted with much lassitude over the census.”

With surprising speed, San Diego’s census total arrived on July 7. San Diegans were stunned. According to the U.S. Census, the city’s population totaled only 15,700. Mayor Gunn was furious. Charging that two out of three people had been missed, the mayor demanded a recount. He took a train to Los Angeles and complained personally to Supervisor Mosher, who promised to take the matter under advisement.

A few days later, Mosher telegraphed Gunn to say that he would come to San Diego and thoroughly investigate “your claim of errors and omissions in the enumeration.” The Los Angeles Times headlined the story: “CENSUS SQUABBLING: San Diego Thinks She Is in the Soup.”

On July 15, the supervisor arrived and settled in at the Hotel del Coronado. Two days of audits followed in a room at city hall. Mosher’s enumerators rechecked their schedules and interviewed more than 200 people who claimed to be uncounted. When the work was over, Mosher’s team added 336 names to the tally. San Diego’s official population was now 16,037.

With the count official, San Diegans swallowed their pride and looked at the bright side. The percentage increase since 1880 was 512 percent versus “only” 350 percent for Los Angeles. The Union noted, “The per cent of increase in population for the last ten years is wonderful to hear, and wonderful to tell.” (Unfortunately, the winner of the A. Dorsey & Company “best guesser” contest went unreported.)

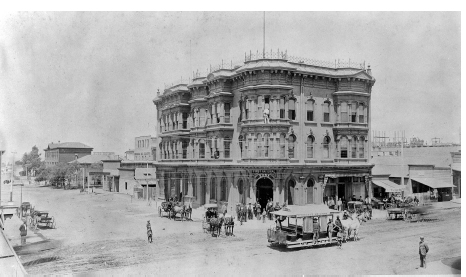

San Diegans may have accepted their results, but nationally, the 1890 U.S. Census was controversial. People were shocked (and suspicious) of the speed of the census count. The eleventh census was the first to be counted by machine; the returns were tabulated from data entered on punch cards. The rough population estimate for the entire country (62 million) was announced after six weeks of processing. The complete 1880 count had taken eight years.

The Hollerith keypunch is shown in this woodcut illustration from Scientific American, August 30, 1890.

The 1890 census is mostly remembered as “the lost census.” In 1921, about 25 percent of the warehoused census schedules was destroyed in a fire in Washington, D.C. But 75 percent of the forms survived the blaze either damaged or untouched. These irreplaceable returns were stored and ignored before a government order authorized their destruction in 1933.

THE GREAT RACE

“Go!” Major General Leonard Wood, chief of staff of the United States army, gave the command…The first automobile in the desperate San Diego–Phoenix race shot forward with a bound.

–San Diego Union, October 27, 1912

In the early 1900s, Southern Californians reveled in auto road racing. One of the most popular events was the annual Los Angeles–Phoenix road race. As a test of fragile machines running on barely existent trails, nothing else compared to the annual dash across the desert.

In October 1912, San Diegans cast envious eyes on Los Angeles as that city prepared for its fifth annual race. Why shouldn’t such a race begin in San Diego, the civic boosters asked? After all, Phoenix was a straight shot from San Diego. A successful showing would also highlight San Diego as the logical terminus for the proposed national “Ocean-to-Ocean Highway,” stretching from Baltimore, Maryland, to California.

A committee led by San Diego businessman and road enthusiast Ed Fletcher proposed to challenge Los Angeles with its own race, starting on the same date and time. Prize money was quickly raised—much of it from the city of Phoenix, which was delighted with the San Diego bid.

Official sanction for the event came from the American Automobile Association (AAA). The races would begin at about the same time, but the Los Angeles drivers would reach Arizona by way of San Bernardino and Indio before turning southwest to Yuma. The San Diego racers would go due east. Despite a detour north after El Centro to avoid several miles of sand hills, the southern path was at least one hundred miles shorter than the Los Angeles route. “We will beat the Los Angeles cars by a full twelve hours, at the very least,” boasted one San Diego driver.

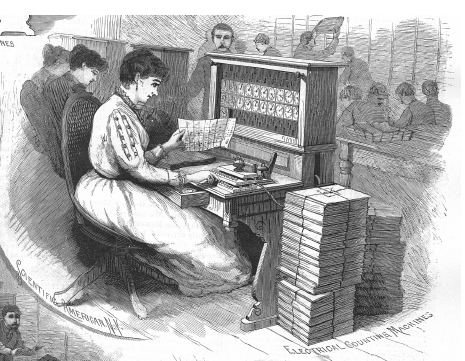

For the most part, Los Angeles ignored the race preparations in San Diego. The Times barely acknowledged its southern neighbor. The Los Angeles Examiner was more enthusiastic and challenged Ed Fletcher to a separate “pathfinder” race between the two cities. Starting earlier in the day than the official entrants, the Examiner car would race to Phoenix via Blythe, ignoring Yuma. Fletcher, represented by the San Diego Evening Tribune, would follow the more direct route due east across the desert. When the Phoenix Gazette joined in as a cosponsor of Fletcher, the car became the “Tribune-Gazette Pathfinder.”

The great race began on Saturday night, October 26. Enormous crowds filled the sidewalks and streets as twenty-two growling race cars lined up on Fifth Street between D and C Streets. At 10:15 p.m., the celebrity starter—Major General Leonard Wood, hero of the Spanish-American War—yelled “Go,” and the first car “shot forward with a bound.” At five-minute intervals, the rest of the field started on their way, speeding up Fifth to University and then east out of town on El Cajon Boulevard.

“Pathfinder” Ed Fletcher drove a twenty-horsepower, air-cooled Franklin to lead the San Diego racers. Special Collections, University of California–San Diego.

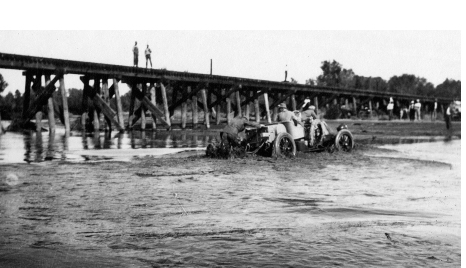

Fording the Agua Fria River on the way to Phoenix challenged the road racers. Special Collections, University of California–San Diego.

Up north, only twelve cars began the traditional Los Angeles–Phoenix version of the great race. According to the Times, “tens of thousands of frenzied men and women” gathered for the start in front of the Hollenbeck Hotel. At 11:00 p.m., the drivers began “the most sensational fight ever waged on the sand of the lonely desert” as they sped east toward Ontario and then southeast into the desert.

The last two cars to start that night were the “outlaws.” Running their own separate match race—unsanctioned by the AAA—were San Diego mayor James Wadham and future mayor Percy J. Benbough. At 12:05 a.m. on Sunday morning, the big touring cars, each carrying three passengers besides the driver, set off toward Arizona for the “honor and glory” of San Diego.

One car was already well on the way to Phoenix. “Pathfinder” Ed Fletcher, driving a twenty-horsepower, air-cooled Franklin, had left early Saturday morning. Fletcher and his three companions decided to ignore the detour taken by the San Diego racers (north toward Niland, to avoid the towering sand dunes east of El Centro) and risk the more direct path, straight through the sand to Yuma. But first Fletcher had to drive through thirty miles of scrubby desert. “The Franklin did nobly,” Fletcher recalled, but he found that eventually small twigs filled his engine and began popping through his cooling system. Fletcher stopped the car and lifted the hood, and the twigs blazed. The men frantically threw sand on the engine to stop the fire.

To negotiate the sand hills, Fletcher reduced his tire pressure to twenty pounds. He had also prudently stationed a horse team in the area. When the car labored in the hub-deep sand, the six-horse team pulled his touring car four and a half miles across the dunes.

It was dark by the time the pathfinder car reached the Colorado River, opposite Yuma. With the ferryboat gone for the night, Fletcher tried the railroad bridge. “We took that risk; used blankets and seats to keep [the rail spikes] from puncturing our tires—but we made it.”

Fletcher’s next obstacle was the weather. Heavy winds and rain beat down as they reached the Hassayampa River, flowing at flood stage but negotiable on another railroad bridge. Downed eucalyptus trees on the trail also slowed their progress. The men sawed through the trees and continued on. Outside Phoenix, the Agua Fria River was crossed by yet another convenient railroad bridge.

Fletcher finally drove into Phoenix—“exhausted but happy”—nineteen and a half hours after leaving San Diego. The competing Examiner pathfinder car never arrived. It had broken down in the desert near Blythe. The next cars to appear in Phoenix were the “outlaws.” Mayor Wadham pulled in at 5:40 a.m. on Monday morning. Percy Benbough arrived two hours later, bemoaning a delay stuck in the sand but claiming a better running time than Wadham. The two men bickered over the result and then agreed to call it a tie.

The official drivers from San Diego and Los Angeles—all delayed by a checkpoint in Yuma—began coming in that afternoon. Only seven San Diegans finished the hard race. D.C. Campbell, driving a Stevens-Duryea, was first with a running time of sixteen hours, fifty-nine minutes.

Los Angeles’s best finish was by Ralph Hamlin in eighteen hours, forty-five minutes. The Times reported his victory with a stirring story of Hamlin’s race. The San Diego Union proudly headlined its account, “SAN DIEGO CAR BEATS LOS ANGELES.”

WONDERLAND

With one swift move of the hand at the big switchboard at “Wonderland” last night, Mayor Charles F. O’Neall of San Diego opened the big playground at Ocean Beach just as the clock struck seven. The blaze of light that followed was a startler to the crowds that were waiting outside the closed gates clamoring for admittance.

–San Diego Union, July 3, 1913

The public sneak preview of Wonderland, two days before its scheduled July 4 opening, delighted thousands of visitors. When Mayor O’Neall threw the switch, twenty-two thousand tungsten lights illuminated the new amusement park at Ocean Beach. The entrance gates—framed by towering minarets—opened, and the throngs poured in, accompanied by a band playing “America.”

For the official opening on July 4, the park added fireworks, with music from the Royal Marine Band. “The Battle in the Clouds” ran all day and into the evening, directed by Signor Paglia, the “famous master of pyrotechnics” and former director of displays for the king of Italy.

The entrance to Wonderland of Ocean Beach. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

More than twenty thousand people came on opening day. The Point Loma Railroad Company ran streetcars every twenty minutes from Fourth and Broadway for the forty-minute trip to Ocean Beach. Buses from Horton Plaza ferried people to the park, one vehicle every thirty minutes.

San Diegans had never seen anything like it. “The most carefully planned and constructed amusement park on the Pacific coast” was built at the cost of $300,000 on eight acres of concrete-paved land south of Voltaire, between Abbott Street and the ocean. Wonderland boasted “40 attractions,” including a dance pavilion, a bowling alley, a half-acre children’s playground, a roller skating rink and a seawater bathing plunge. A zoo featured lions, bears, leopards, wolves, mountain lions, a hyena and fifty-six varieties of monkeys—all housed and “waiting for the givers of peanuts and popcorn.”

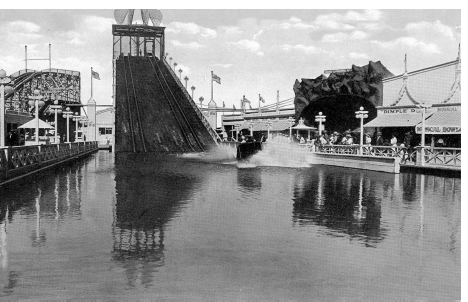

The fun zone—on the model of Coney Island’s famed Luna Park—included a water slide, a carousel, carnival games and the biggest roller coaster on the Pacific Coast. The wooden coaster, called the Blue Streak Racer, ran two cars, which raced each other on parallel tracks over a 3,500-foot-long course.

Chute-the-Chutes was a popular steep waterslide ride. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

Reflecting the conservative mores of the day, the family-oriented Wonderland was advertised as “morally clean,” safe and wholesome. Violators of respectability risked expulsion. “There will be no ‘mashing’ anywhere in the park,” the management declared. Unseemly behavior in the Waldorf Ballroom required particular vigilance. To ensure that there was no “turkey-trotting” or “bunny-hugging” on the dance floor, a Mrs. Margaret Madden kept a watchful eye.

Ruth Varney Held, in her 1975 book Beach Town, recalled her experience at Wonderland as a seven-year-old:

I was there, starry-eyed. I paid my ten cents at the booth between the fancy towers, drifted in, and gasped in awe…Monkeyland charmed me first, with 350 monkeys making funny faces and reaching for tidbits. One was the mischievous Mr. Spider, advertised as “The oldest monkey in captivity,” who might reach out through the bars with his tail and whisk your hat off. My next love was the Chute-the-Chutes, a high, steep water-slide. Flat-bottomed boats shoved off from the top, to whoosh down into the pool below, spraying water over the shrieking passengers.

Held marveled at the apparent success of the park, noting that “one of the great wonders of Wonderland was how San Diego could support such a large amusement park.” After all, the population of San Diego barely exceeded sixty-five thousand, and Ocean Beach had perhaps three hundred people.

Against such odds, Wonderland thrived for only two seasons. For all their careful planning, the operators of the park failed to consider the prospect of competition. The opening of the Panama-California Exposition in 1915 slashed attendance, and the park fell into foreclosure. In March 1915, Wonderland was sold at auction.

To add insult to injury, turbulent ocean tides undermined the foundations of the giant rollercoaster and closed the park’s premier attraction in January 1916. The Blue Streak Racer was dismantled and shipped to Santa Monica, where it ran at the Pleasure Pier for many years.

The most enduring legacy of Wonderland would be its small zoo. When the Panama-California fair began in Balboa Park, the menagerie was rented to the exposition company for $40 per day. Housed in a series of cages near Indian Village on Park Boulevard, the collection of animals was eventually sold to the city for $500. The well-traveled animals would appear again when the San Diego Zoo opened in 1922.

BABE RUTH IN SAN DIEGO

George Herman Ruth, world’s greatest baseball player, came into our midst on the noon train today slanting one eye at his traveling bag and the other at the overcast sky. “Low visibility,” quoth the Babe. “But if the raindrops will stay away for a short time I guess I can get the range and park a few baseballs on the far side of your famous stadium.”

–San Diego Tribune, October 29, 1924

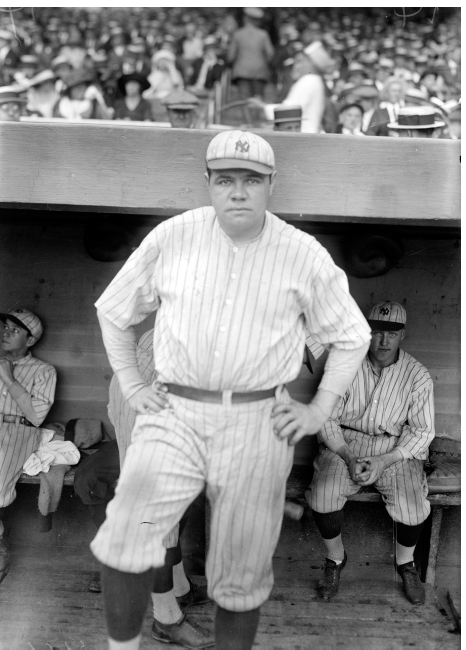

The most celebrated player in baseball history was a frequent visitor to San Diego. “Babe” Ruth made several trips to the city as an exhibition ballplayer, performed in a local theater show and, for time, even contemplated building a home in La Mesa.

Ruth first visited San Diego on December 28, 1919, only two days after his famous sale to the New York Yankees by the Boston Red Sox. Already a prolific home run hitter at age twenty-four, Ruth had finished the 1919 season with a record twenty-nine home runs, a mark he would improve repeatedly in the following fifteen years as a Yankee.

Home run hitter Babe Ruth delighted San Diegans with his off-season appearances at City Stadium. Library of Congress.

Ruth’s visit was the first of many “barnstorming” tours he would make across the country following the end of the regular major-league season. The games were hugely popular in every town, where Ruth and fellow big leaguers would play with local amateurs. Batting exhibitions preceded each contest, ensuring Ruthian home runs, even when the Babe failed to hit one out during a game. Many games never finished because fans tended to swamp the field in the late innings to meet their hero up close.

In the Sunday afternoon game at the City Stadium (later known as Balboa Stadium), Ruth’s “All-Stars” beat a San Diego amateur team, 15–7. Ruth (an outfielder for the Yankees) played first base, where he “bungled a couple” of chances, according to a Tribune reporter. But he redeemed himself in the ninth inning when he delivered what the crowd of 6,500 had come see: a home run that “soared and sailed like a shot” an estimated four hundred feet.

Ruth returned to San Diego five years later, near the finish of a fifteen-city tour. The weather had been rainy on October 29, 1924, but a “liberal supply of sawdust in the wet spots” made the field playable. Nearly three thousand fans braved the chilly breeze at City Stadium, paying seventy-five cents for adults and twenty-five cents for children under twelve.

In the pregame warm-ups, Ruth and his Yankee teammate Bob Meusel put on a home run clinic, driving several balls into the concrete stands. Reporters noted that “Ruth has a very peculiar stance at the plate, and certainly takes a terrific ‘cut’ at the ball.” In the game itself, Ruth had four hits and no homers, but his team beat the “San Diegos,” 10–6.

Between innings, “hundreds of youngsters” swarmed the bench to get Ruth’s autograph on “a baseball, card, or piece of paper.” A reporter noted that Ruth played the entire game with a pencil behind his ear, “ready for instant use.”

The Babe made a winter visit to San Diego in 1927 to work a one-week vaudeville engagement at the Pantages Theatre on Fifth and B Streets. The week of January 10, Ruth performed three shows per day, giving hitting demonstrations and performing a skit that celebrated his recent baseball feats. Each show concluded with the Babe’s invitation to kids to come on stage and receive autographed baseballs.

Apart from his three-a-days at the Pantages, Ruth kept a hectic leisure schedule in the company of friends: playing golf at the Coronado Country Club, duck hunting on Sweetwater Lake and deep-sea fishing off Point Loma. Ruth also found time to purchase a La Mesa homesite in the new Windsor Hills tract on the southern slope of Mount Nebo. Ruth decided to hold the lot for investment purposes, being “sold” on San Diego.

Yankee slugger Babe Ruth with a young fan at City Stadium, October 29, 1924. San Diego History Center.

The January visit had a strange epilogue. When Ruth traveled to Long Beach for another vaudeville show, he was met by sheriff’s deputies and arrested. A warrant was served for violating child labor laws in San Diego. A zealous deputy state labor commissioner, Stanley Gue, had accused Ruth of making children a part of his act at the Pantages without obtaining required work permits. A second violation charged him with keeping the children on stage after a 10:00 p.m. curfew. Ruth posted $500 bail and departed for New York. The next month, a San Diego judge dismissed the charges and ridiculed Commissioner Gue for demanding licenses for children “to step up onto a stage to get a free baseball.”

Under happier circumstances, Ruth returned to San Diego in October. The slugger had just finished a triumphant Yankees season with a World Series title and a new record of sixty homers—a mark that would stand for thirty-four years. The Babe’s visit came near the end of a nine-state, twenty-one-city tour. On this trip, he was joined by a rising young Yankees star, Lou Gehrig. Babe wore a tour uniform of all black, with white lettering emblazoned “Bustin’ Babes.” Gehrig’s white uniform was lettered in black with “Larrupin’ Lous.”

In the October 28 game, sponsored by the American Legion, Ruth’s team beat Gehrig’s, 3–2. Competition for souvenir baseballs hit by the “Homerun Twins” was fierce. “Every time that Ruth or Gehrig cracked one off the diamond, it was a signal for hundreds of the youngsters to make for the spot on the run, and then would follow a free-for-all struggle for possession of the prized agate.”

Ruth’s last appearance in San Diego was witnessed by 3,500 fans. The afternoon game was called on account of darkness at the end of the seventh inning. The fans were satisfied. “There were no home runs hit,” the Union reported with regret, “but the two Yankee sluggers gave a mighty account of themselves just the same.”

THE “STOLEN” CABRILLO STATUE

“I didn’t steal it,” declared Senator Fletcher with ruffled dignity. “But there were threats of lawsuit and an injunction, so with a gang of men, a derrick and a truck, I took quick action, and possession is nine points of the law.”

–Los Angeles Times, March 1, 1940

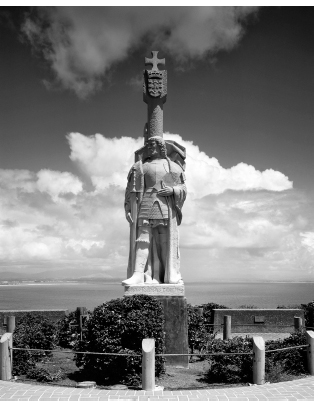

For more than six decades, the figure of Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo has watched over San Diego Bay from the heights of Cabrillo National Monument on Point Loma. The fourteen-foot sculpture is an icon to San Diegans, who know Cabrillo as the sailor who entered our port in 1542, the first European to visit California.

A statue commemorating Cabrillo had long been sought by San Diegans, particularly by the Portuguese community, which claimed the explorer as one of its own. In the 1930s, the artist Alvaro de Bree was commissioned by Portugal to create the now familiar sandstone sculpture. A decade of controversy would follow.

As a gift to the State of California, the Cabrillo statue was sent to San Francisco in 1939 for the Golden Gate International Exposition. But it arrived too late for display and languished instead in a federal customs warehouse. A six-foot replica served as a stand-in at the fair.

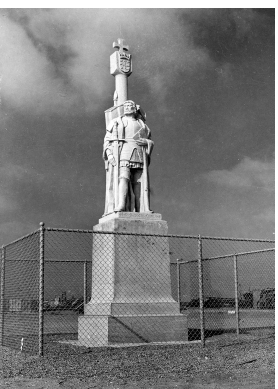

The statue of explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo at Cabrillo National Monument on Point Loma. Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress.

After the exposition’s conclusion, Governor Culbert Olson formally accepted Portugal’s gift. Released from the customhouse, the statue was sent for safekeeping to a private residence in the bay area. The ultimate destination, decided Governor Olson, would be the city of Oakland in Alameda County, home to more than sixty thousand people of Portuguese descent.

The governor’s decision outraged San Diegans, who believed that the most appropriate site for the statue would be the port where Juan Cabrillo originally landed. The community was also anxious to make the figure the centerpiece of a planned Cabrillo celebration, marking the 400th anniversary of the explorer’s visit to California. Joseph Dryer, president of the Heaven on Earth Club, enlisted the aid of California senator Ed Fletcher to bring the Cabrillo statue to San Diego.

The statue “was a prize worth fighting for,” thought Fletcher. The senator took the offensive, securing a legal opinion from his Sacramento colleagues that held that the legislature—not the governor—would determine the permanent home of the statue.

Next, with the aid of Lawrence Oliver, founder of San Diego’s Portuguese-American Club, Fletcher located the statue at the home of a former Portuguese national near San Francisco. Fletcher and his wife, accompanied by Senator George Biggar and his wife, paid a visit to the house, where the crated, seven-ton statue lay on the floor of the garage. “It was so heavy it had broken the concrete in the garage floor. We discussed the matter with the lady, found she was sympathetic, and convinced her the statue should go to San Diego. Her husband having died recently, she wanted it out of the garage, but insisted upon some authority from the state before having it moved to San Diego permanently.”

Fletcher introduced a bill in the state Senate that designated San Diego as the permanent home of the Cabrillo statue. The senators passed the resolution unanimously, but it died in an assembly committee, killed by an assemblyman from Oakland. Fletcher’s only thought was to get possession of the statue.

Armed with a letter of authorization from the State Park Commission and a copy of the State Journal showing the approval of the Senate, Fletcher returned to the house. The widow viewed the “documentary proof” and consented to the statue’s removal.

Earlier in the day, Fletcher had arranged for movers to be ready at a moment’s notice. Now he called in the movers, and a crew of four arrived with a “tremendous” truck. The men hefted the statue onto rollers and pushed it out to the sidewalk. Then the telephone rang:

She called me into the house and asked me to talk over the phone to the Vice-Consul of Portugal who protested its removal and threatened court proceedings. I also got another telephone call from an attorney in Oakland who threatened an injunction. The lady was in tears, but it was too late. I promised her she would never regret it and left with the statue.

Fletcher’s crew hauled the statue to the Santa Fe railroad depot and put it on an evening train for San Diego. The statue was soon safely locked up in a San Diego warehouse under the care of City Manager Fred Rhodes.

The uproar was immediate. Oakland’s Portuguese community demanded an investigation. Alameda assemblyman George P. Miller filed a protest with Governor Olson, and the governor himself publicly accused Senator Fletcher of “kidnapping” Cabrillo. The furor slowly died as bills introduced in the legislature to retrieve the statue were defeated in committee.

San Diego dedicated the statue on the grounds of the Naval Training Center near Harbor Drive in December 1940. Here the sculpture remained for the next several years, behind a fence and out of public view. Plans for the statue’s starring role in the Cabrillo quadricentennial ended when the festival was canceled due to World War II. Instead, a simple ceremony honoring Cabrillo was held on September 28, 1942. Dr. Reginald Poland, director of the San Diego Fine Arts Gallery, praised the statue as “a fine work of art” and “a fortunate balance of the natural and abstract.”

The statue was finally moved to Cabrillo National Monument in 1949, where it was erected on a five-foot pedestal north of the lighthouse. An elaborate rededication ceremony on September 28 honored the “discoverer” of San Diego. The statue would later be moved closer to the visitor center at a spot overlooking the harbor.

Time would not be kind to the sandstone sculpture. Weathering badly in the ocean air and suffering from “visitor abuse,” it was brought indoors for restoration in the 1980s, never to return. An exact replica sculpted out of denser limestone was dedicated in 1988.

Today, the figure of Cabrillo still stirs controversy. The assumed Portuguese nativity of Juan Cabrillo is doubted; many historians now believe that the navigator was Spanish. Scholars also question the statue’s appearance, finding the presentation unauthentic. Without question, though, the storied statue continues to be a star attraction for one of the most visited national monuments in the country.

San Diego dedicated the Cabrillo statue on the grounds of the Naval Training Center in December 1940, where it remained hidden from public view for the next several years. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.