PART IV

SINS OF THE CITY

THE LIQUOR FIXERS

The Police Department got the liquor, fixers got the money, and the Legionnaires laughed.

–Abraham “Abe” Sauer, editor and publisher, San Diego Herald

In mid-August 1929, the California posts of the American Legion gathered in San Diego for its eleventh annual convention. By boat, auto and train, the “joyous, ebullient crowd of World War veterans” poured into the city, filling the streets and hotels of downtown San Diego.

The newspapers noted the “carnival spirit” brought by the conventioneers. Although prohibition was the law of the land, the legionnaires seemed to anticipate a “spirit-filled” good time in San Diego. Like most convention cities, San Diego was expected to ignore the dry laws on behalf of its visitors.

To ensure an ample supply of quality liquor, an “irrigation committee” of legionnaires approached San Diego’s best-known bootlegger, Charlie Muloch, several days before the convention began. Muloch produced liquor from several local stills—from Pacific Beach to Lemon Grove—and dispensed his product from a “health clinic” on Fourth Street. Muloch agreed to supply the convention with “good, safe liquor,” cementing the deal by offering to donate one dollar to the irrigation committee for each gallon sold.

“I am not going to bother conventions,” promised Police Chief Arthur Hill. San Diego Police Museum.

Police officer George Churchman, head of the “police morals detail,” in 1929. San Diego Police Museum.

Security for the operation would not be an issue. The bootleggers had approached Mayor Harry Clark and Police Chief Arthur Hill before the convention, and both officials agreed to “see, hear, and do nothing.” “I know how it is when conventions come,” Hill told the men. “I am not going to bother conventions, particularly the American Legion.”

With the law fixed, Muloch and several associates opened a storeroom at 858 Seventh Street, not far from the convention site at the auditorium of San Diego High School. Six telephones were installed to take orders. Everything appeared to be in order. But two days before the convention opened, on Saturday night, August 17, a police vice squad raided the room on Seventh.

Chief Hill may have known of the bootlegger’s plans, but no one had bothered to inform Lieutenant George Churchman, head of the police morals detail. A tip from someone “sore at the Legion” had mistakenly gone to Churchman instead of Hill. The conscientious lieutenant and his squad arrested five men at the scene and grabbed 4,500 bottles of gin and whiskey valued at $27,000.

Three days later, the American Legion closed its “largest and best” convention with resolutions lauding San Diego as a host city. Presumably, the legionnaires had found adequate alternative supplies of liquid refreshments. Vendors from Los Angeles and Tijuana had taken up the slack.

But for San Diego civic officials, the embarrassment of a “liquor fixing” scandal was only beginning. The city’s three daily newspapers questioned the apparent openness of the liquor sales. Abe Sauer, editor of the weekly Herald, flatly stated, “Somebody paid money to somebody in return for permission to violate the law.”

The city council loudly promised to study charges that “higher-ups” had protected local vice. Its inquiry would “take the stigma off many innocent officials,” Councilman J.V. Alexander pledged. Police Chief Hill was directed to “lend every possible aid to the investigation.”

The first serious probe of the scandal came from the county grand jury, which began grilling city officials and local legionnaires in September. Little of the jury testimony was revealed, but the newspapers reported that a local printer had testified about a leaflet printed before the convention, listing “trustworthy” telephone numbers “which the thirsty were advised to call.”

The local investigation stepped aside when the federal grand jury took up the case. Sixteen San Diegans were indicted on charges of conspiracy to violate the National Prohibition Act. Surprisingly, San Diego officials were spared, but a dozen bootleggers were indicted, along with four men alleged to be the “fixers.”

Charlie Muloch was the star defendant when trial began in federal court on January 20, 1930. The bootlegger described how the “irrigation committee” from the American Legion had requested his services as a single-source supplier, to protect their conventioneers from “poison liquor” from unknown vendors. Muloch had agreed to furnish good liquor at $4.50 per bottle. The committee had assured the bootlegger that there would be no interference from the authorities.

The base of operations would be the supply room on Seventh Street. Business cards were printed with the phone numbers of the room. As protection against hindrance from police, tickets called “Buddy Cards” were distributed as get-out-of-jail cards.

But then “the knock-over” came on August 17. Muloch and four others were arrested and their booze taken. The Buddy Cards “did not function as expected,” Muloch lamented. When the bootleggers were taken to police headquarters at 732 Second Street, Lieutenant Churchman was standing out front. “They seemed confused and didn’t know what to do.”

Federal authorities had been more decisive and appropriated the liquor within hours of the knock-over. Muloch revealed that more government raids in the following days had cost him about $100,000 in lost liquor taken from his other “plants” in the city. “I do believe there were some arrangements to fix the authorities,” he testified. But the protection had only been an assumption.

On January 24, the federal grand jury announced guilty verdicts for six men. Another five defendants, including Charles Muloch, had already pleaded guilty. Sentences ranged from twenty days in jail to six months.

The unindicted mayor of San Diego and his chief of police would soon be out of office. Harry Clark was defeated in a bid for reelection in April 1931. Arthur Hill would be demoted by the new mayor to the rank of captain and assigned to the traffic squad. Lieutenant Churchman retired the next year at age forty-three and drew a city pension until his death at age ninety-five.

THE RUMRUNNERS

San Diego, San Pedro and Santa Barbara have become the focal point of the rum runners operating on the Pacific coast…It is believed that the bulk of the rum fleet will arrive in southern California waters, literally flooding this part of the state with booze of all descriptions.

–San Diego Union, May 12, 1925

The “noble experiment” of prohibition—which outlawed most manufacture, sales and transportation of intoxicating liquor—began in 1920 with the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment. An assortment of unintended consequences accompanied prohibition, including a rise in organized crime.

One example was rumrunning from America’s wet neighbors—Canada and Mexico. It was perfectly legal for these countries to import and sell liquor. Canadian imports of liquor grew sixfold during prohibition; Mexican imports grew eightfold. Most of this alcohol would be smuggled into the United States, across the border and by sea.

A visible symptom of prohibition was “Rum Row.” Along both the Atlantic and Pacific seaboards, scores of smuggler ships lined the coastline. These foreign-flagged “mother ships” brought tons of liquor to America, anchored in international waters (three miles offshore) and fed swarms of small “contact boats” that brought the contraband to shore.

The profits from smuggling liquor were enormous. A Time magazine exposé in 1925 tallied the takings: “A case at Rum Row, $25; on the beach, $40; to the retail bootlegger, $50; to the consumer, $70 or $6 a bottle.”

Defending America against this wet onslaught was the U.S. Coast Guard. Undermanned and underfunded, the Coast Guard attempted to protect a six-thousand-mile coastline. The job was mostly futile at first. But between 1924 and 1926, personnel grew by 50 percent. Scores of new ships were added to the service in an attempt to match the growing number of smuggling vessels. New international agreements helped. In 1924, maritime nations agreed to recognize a “twelve-mile limit” that allowed the seizure of ships up to “one hour steaming distance” from shore.

In the summer of 1925, the Coast Guard went to war against the rumrunners. Concentrating its forces against the major smuggler fleets off the New York coast, the service managed to capture some of the fleet and scatter the rest. It was considered a major success, but only for the East Coast. The rumrunners relocated and redoubled their efforts elsewhere, particularly off the coast of Southern California.

As the Atlantic smuggler fleets declined, the Rum Row off Southern California grew. Breathless newspaper reports announced the arrival of each summer’s liquor armada: “A huge rum fleet, carrying cargoes valued at several million dollars, is lying off Southern California,” the Los Angeles Times reported in May 1925. And the following summer: “Sixteen British, Belgian, Panamanian and Mexican rum-runners, the greatest mobilization of liquor-laden ships in the history of the Pacific rum-running, are hovering off San Diego.”

The usual practice was for the fleet of mother ships—the Rum Row—to anchor many miles offshore (respecting the twelve-mile limit), in locations ranging from the Channel Islands to Ensenada. A popular anchorage was the shallow waters of Cortes Bank, about one hundred miles west of Point Loma.

A notorious mother ship of the Pacific Coast rumrunners was the five-masted schooner Malahat. Vancouver Maritime Museum.

The best-known mother ship for the rumrunners was the Malahat, an auxiliary-diesel, five-masted schooner from Canada. Capable of carrying as many as sixty thousand cases of liquor, the schooner would arrive in the Southland with liquor loaded in its home port of Vancouver, British Columbia.

Sometimes the Malahat and other big mother ships like the Mogul, Principio or Marion Douglas would wait along Rum Row for freights of liquor arriving from Europe, Australia, Tahiti or Mexico. The smugglers would then load smaller “intermediate” boats that moved the cargoes closer to the coast. Finally, on dark nights, speedboats arrived to whisk the illegal booze to shore and to trucks waiting on the beach.

The Coast Guard could do little but annoy the rumrunners. Its task was to watch the mother ships and intercept the movement of liquor to shore. Its only weapons were the Los Angeles–based Vaughan, an aging World War I sub-chaser, and the San Diego–based Tamaroa, an ex-tugboat so slow it was called “the sea cow.”

The smuggler boats were faster than anything the Coast Guard had. Many were powered with a popular war surplus airplane engine—the four-hundred-horsepower Liberty V-12, which pushed the boats to speeds of forty knots. The workhouse engine of World War I fighter planes became the motor of choice for the rumrunners.

Shortwave radio communication linked the speedboats to the mother ships and to watchers on shore. A Coast Guard official observed, “The rum runners have perfected a system of communication that is little short of marvelous. There have been times when a fast launch loaded with liquor broke down when nearing shore. In a very short time a rescue boat would appear, the liquor would be transferred and the crippled boats would sail into port for repairs.”

The local Coast Guard began to get some help in the mid-1920s. Fresh from success on the East Coast, the government transferred several fast cutters to Southern California. Ten new patrol boats armed with cannons were commissioned in San Francisco and sent south. Augmenting the Coast Guard fleet were several confiscated rumrunner boats (including a speedboat called Skedaddle, reportedly built for newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst).

While victories at sea remained few, major successes against smuggling came on land. In November 1926, federal investigators announced the breakup of a Vancouver syndicate known as the Canadian Consolidated Exporters Limited. Believed to virtually monopolize Pacific Coast rumrunning, the syndicate controlled most of the mother ships, including the flagship Malahat. With the syndicate exposed, Canadian authorities began their own investigations, which complicated business for the smugglers.

But the rumrunners persisted. Sightings of liquor-laden ships off Southern California’s coast continued into the late 1920s. Only the repeal of prohibition in 1933 brought an end to the lucrative trade and the thirteen-year war against Rum Row.

On June 17, 1934, the Los Angeles Times printed an obituary for the smugglers: “The steamer Mogul, once the pride of San Diego’s rum row, is now on her way home, to Vancouver, B.C., the loser in her long battle with United States customs officers and Coast Guard…Thus has California’s rum row gasped its last breath.”

A GAMBLING WAR IN THE CITY

On Monday morning, July 22, 1935, San Diegans opened their morning newspaper to see a stunning headline: “AGUA CALIENTE PADLOCKED.” The enormously popular resort and casino in Tijuana was closed following the order of President Lázaro Cárdenas to end gambling in Mexico.

The closing of the lavish resort sent shudders across the border. Agua Caliente had been massively profitable to the resort’s American owners but also to San Diego merchants, who earned an estimated $300,000 monthly supplying goods and services. Public officials voiced concern about the end of gambling in Tijuana. Would illegal gaming now grow in San Diego? Police Chief George Sears assured the public that “the gambling lid was on.”

But the “lid” was teetering. Long known as an “open town,” officials often turned a blind eye to illicit activities that boosted the city’s reputation as a mecca for tourists and the military. Despite occasional vice raids to clean up the town “once and for all,” gambling and prostitution flourished north of the border.

San Diego was also viewed as a region where public officials could be “bought.” Abe Sauer, the cynical newspaper publisher of the local Herald, railed weekly against officials he judged corrupt. But Sauer recognized that vice could also be means for favorable publicity, noting that “whenever a chief of police or a district attorney or a sheriff wanted to land on the front pages of the local papers he staged a gambling raid.”

Sauer, then, was not surprised on October 16, 1935, when the newspapers heralded one of the biggest raids in several years. Storming a “palatial residence” near Imperial Beach, sheriff’s deputies arrested several men and confiscated $15,500 worth of gambling paraphernalia that appeared remarkably similar to equipment recently used in the now closed Agua Caliente casino.

The entire house was fitted out as a casino, with each room set up for a specific game: blackjack in one room, poker or roulette in other rooms. The deputies found a large kitchen stocked with sandwiches and liquor, and rooms were decorated with antiques and hand-carved furniture. Heavy velvet drapes hung from the walls to cut down on noise.

Outside the house, a tall pole stood on a corner of the lot with a blue light on top. Visible for two miles, the light burned brightly on nights when gaming was underway. Four “owners” of the house were eventually convicted of gaming charges, with sentences ranging from ten to twenty days.

City police officers had their turn for glory on November 13 with a raid on the San Diego Club at 1250 Sixth Avenue. The police gathered up slot machines, roulette wheels and club “script.” Gamblers escorted out by police included a former city councilman, a county grand juror and several prominent businessmen. Only the day before, in a luncheon speech at the U.S. Grant Hotel, County Assessor James Hervey Johnson had declared that the “tentacles of San Diego’s underworld reach right up to officialdom.”

The San Diego County Jail was built directly behind the courthouse at Front and C Streets in 1912. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

The following week, Police Chief Sears threw a surprise blockade on a dozen bookmaking venues and closed several gambling clubs and “all known houses of prostitution.” The Saturday night raid also stopped the biggest gaming joint in town: the Hercules Club at 752 Fifth Street. “The raid was spectacular in the extreme,” reported an amused Abe Sauer. Hundreds of people watched from the sidewalk as forty-seven men were arrested and trucks were loaded up with gambling equipment.

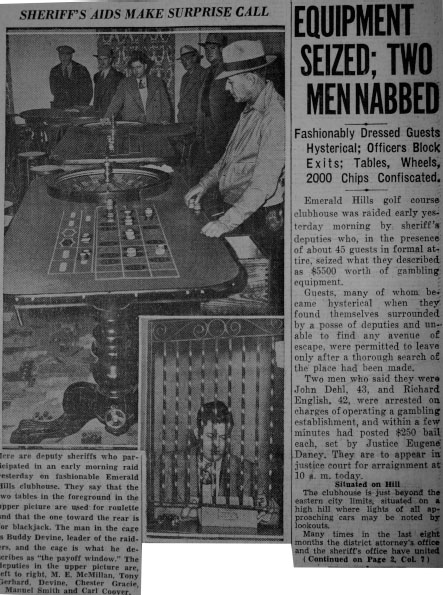

San Diego’s showy war on gambling reached a climax with a Christmastime raid on the Emerald Hills golf course in southeast San Diego. From the clubhouse, located on a hill just beyond the city’s eastern limits, lookouts could spot the headlights of approaching cars. But the watchers missed the arrival of sheriff’s deputies in the early morning hours of Sunday, December 8. The raiders broke in to surprise nearly one hundred men and women in formal attire, sipping champagne and playing roulette and blackjack.

At Christmastime, the police raided a thriving casino set up in a golf course clubhouse. From the San Diego Union, December 9, 1935.

Panicked women gathered up their trailing gowns and tried to flee through the doors, only to be turned back by deputies stationed at all the exits. One elderly man tried to leap from a window but was grabbed by the heels and dragged back inside. A deputy broke a kneecap as he wrestled with “a prominent local banker.”

The deputies made only two arrests and allowed the rest of the gamblers to leave after taking their names. They confiscated two thousand chips, forty money bags and hundreds of dollars in cash, checks and IOUs abandoned at the gaming tables. The seized club roster resembled a social register of San Diego, with scores of well-known names.

Smaller raids came in 1936, and the year ended with Sheriff Ernest Dort declaring the county free of gambling and “clean as a bone.” But more pragmatic minds were at work when the city council decided that rather than shut down all gambling, it was time for government to take its fair share of the proceeds. In November, the council members approved the licensing of “pin-marble” game machines and began collecting monthly rent from the gambling equipment. California senator Ed Fletcher followed the next year with a bill to collect income taxes from gambling, although he took pains to stress that “nothing in this act shall sanction any form of gambling which is prohibited by law.”

The Agua Caliente resort never reopened. The Mexican government opened a state-run school at the site, the Instituto Tecnológico de Tijuana, in October 1939. It remains a school today, but the elegant buildings designed by Los Angeles architect Wayne McAllister have mostly disappeared.

THE SHORT-LIVED CAREER OF CHIEF HARRY RAYMOND

In the early 1900s, few jobs were more tenuous than chief of the San Diego Police Department. The pressures of city politics kept careers short, averaging eleven months between 1927 and 1934. The tenure of Chief Harry J. Raymond was briefer than most and maybe the strangest.

Police Chief Harry J. Raymond. San Diego Police Museum.

Raymond became chief on June 5, 1933. With more than twenty years of police experience, largely as an investigator for the Los Angeles district attorney’s office, he brought to the job a “reputation for efficiency in force management,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

His appointment to the $300 per month job by City Manager Fred Lockwood, though, was instantly questioned. San Diegans were unhappy that Lockwood had bypassed department candidates to hire a detective from Los Angeles. The manager cited the need to reorganize the police: “It is my understanding that there are three or four cliques in the department and an outside man could break them up better than a man in the department.”

There were also sensational rumors from Los Angeles of unsavory links between Raymond and the underworld. Two local attorneys claimed that Raymond had taken calls from grifters and “bunco artists,” asking him to come to San Diego. But defenders of the new chief believed that he would clean out much of the “petty racketeering” thought to be growing in the city.

Within a month of his hiring, Raymond announced sweeping changes in his department. To “distribute efficiency” and place men in “more active positions,” he ordered the transfers of more than one hundred police officers. The biggest staff shakeup in department history sent several veteran officers—including two former chiefs—from headquarters to substations at Ocean Beach, La Jolla and East San Diego.

In the opinion of Abe Sauer, the crusading editor of the weekly Herald, Raymond’s changes “turned the department upside down and left it with its head in the dust and its legs kicking idly in the air.” Sauer protested that “competent officers were switched from section to section until they don’t know where to report for work. Everyone who was presumed to know anything was put where he couldn’t be heard.”

Throughout the summer of 1933, there was a drumbeat of criticism from the San Diego Union. The newspaper complained that police work was being politicized by Chief Raymond. An editorial cited a spiteful raid on a nightclub and the arrests of several out-of-town entertainers. It was “apparent that the raid was not a police matter but a political matter.”

A “loud-mouthed squabble over a midnight glass of beer” proved to be the turning point in Chief Raymond’s unpopular San Diego career. As reported by the Union, Raymond was a customer at the popular Hof-Brau nightclub at State and C Streets, where he ordered a beer, late on Saturday night, August 26. The beer was “served tardily,” and the chief complained to the management that he was not given proper attention.

Raymond then made a phone call from the nightclub to George Sears, head of the police vice squad. A short time later, the chief met the vice squad at police headquarters, where the Sears was ordered to proceed to the Hof-Brau and to “stop dancing at 12 p.m., confiscate gambling paraphernalia, [and] make arrests of all drunken persons and anyone causing a disturbance.”

Sears dutifully led his squad to the Hof-Brau at midnight. The music and dancing was stopped, slot machines were dragged outside and the nightclub was closed. James Crofton, part owner of the club, protested to Sears, demanding to know why he was being singled out. When Sears called Raymond and relayed the complaint, the chief ordered police radio patrols to close all beer halls on their beats and to make appropriate arrests.

More raids quickly came, and the police arrested nearly thirty people suspected of public drunkenness. As the police closed the Momart Café on Atlantic Street (now Pacific Highway), the owner protested. “There was a city councilman here only a few minutes ago. He told me this was a good place!”

By Monday morning, a public uproar over the police raids was front-page news. Those arrested over the weekend—including a handful of agitated attorneys and politicians—were quickly released by a justice court judge. The Union accused Raymond of humiliating “ordinary San Diegans” to gratify a petty grudge and demanded his resignation.

The besieged chief denied personal malice and insisted that his orders were only intended to enforce a local ordinance that prohibited dancing after midnight. But Raymond’s defense was challenged by City Attorney Clinton Byers, who said that there was no closing hour specified for the dance halls and nightclubs.

“I am not going to hand in my resignation to anybody at any time,” announced Raymond after a week of rumors. But City Manager Fred Lockwood had seen enough and asked for Raymond’s resignation. When the chief ignored the request, Lockwood politely waited one day and then informed Raymond by letter that his services as chief of police were no longer required.

“Raymond is not the man for the police job,” Lockwood said. “He has shown no executive ability. He is temperamentally unfit for the post.” The ex-chief threatened action against the city council to reclaim his job but then quietly left town for Los Angeles, where he resumed an eventful career as a private investigator.

Lockwood replaced Raymond with Lieutenant John T. Peterson, a likeable former chief who had been exiled to the East San Diego substation by Chief Raymond. “Pete” Peterson served for one year, only to be replaced by George Sears, who retained the post for nearly five years.