PART V

ON THE BORDER

THE HOLE IN THE FENCE

Scores of Americans found themselves suddenly stranded in Mexico last night when the famous “hole in the fence” at the border was closed yesterday afternoon without warning…Protest was made to customs and immigration officials on duty, but the officers said they could do nothing about it.

–San Diego Union, December 20, 1930

It had been there for years: a narrow hole clipped from the barbed wire fence separating San Ysidro and Tijuana. Since the late 1920s, thousands of American tourists returning from Mexico had squeezed through the opening at night, bypassing the big iron gates at the international border that closed promptly at 6:00 p.m. daily.

The fence itself had by built by the Federal Bureau of Animal Industry; it was not an immigration fence. The U.S. government was unconcerned by illegal aliens at the international border. The wire fence was there to stop cattle. Mexican steers, it seemed, often wandered across the border, sometimes carrying ticks that infected American cattle.

Most visitors to Tijuana paid little attention to the fence as they walked or drove across the border each day through Gate 1. San Diego motor coach operator Fred Sutherland did a booming business transporting people from downtown San Diego. Others came on trains from the San Diego & Arizona Railway, which ran several times a day for round-trip fares of one dollar.

The celebrated Mexicali Beer Hall in Tijuana offered tourists “the longest bar in the world.” Special Collections, University of California–San Diego.

Prohibition had turned Tijuana into a mecca for thirsty Americans eager to visit the cantinas on Avenida Revolución. Others were attracted to the Caliente Race Track or the casino gambling at Agua Caliente, “the most elaborate pleasure resort in North America,” according to Time magazine. But Tijuana was strictly a daytime adventure. San Diego area churches, PTA groups, women’s organizations and many politicians wanted an early-evening closure to protect public morals from the “injurious effects of wide-open towns.” After Gate 1 closed at 6:00 p.m., no one was allowed to enter the United States—officially, that is.

Only a few paces east of the gate, a hole in the fence provided easy passage into the United States. Federal officials occasionally glanced at the “accidental” hole and sometimes questioned the evening entrants about their nationality or checked them for suspicious bulges in their clothing. For the most part, public use of the hole was a matter of course.

But on Friday night, December 19, 1930, scores of Americans were surprised to find the familiar gap in the “cattle fence” sealed up tight. A few scaled the fence and were grabbed for questioning by customs officials. Others retreated to Tijuana to look for hotel rooms. And some spent the night in the open, waiting for the Gate 1 to reopen at 6:00 a.m. The San Diego Union reported that many of the stranded were frantic women, “thinly clad and unprepared for the cool night weather.”

The next day, Dr. Jan Madsen, head of the local office of the Bureau of Animal Industry, revealed that the fence had been repaired at his direction to keep out stray Mexican livestock. “It is a government fence and it is my business to see that it is kept in repair at all places at all times.” Stranded Americans were not Madsen’s concern. It was “a matter for the customs department, not mine,” he added.

By Saturday night, several new holes had appeared in the border fence. Enterprising Mexican boys armed with flashlights earned tips by showing Americans where to enter their native country. “Among those making use of the newly-discovered openings,” reported the Union, “were several fashionably-dressed men and women who were said to have passed the evening at Agua Caliente. In trying to squeeze through the small openings in the fence some of the plump women and fat men became entangled in the barbed wire, but quickly were extricated by friends or their guides.”

In March, agriculture officials installed a turnstile in the original hole, seven feet east of the main auto gate. Made of pipes painted yellow, the turnstile turned in only one direction (north), could not be locked and was meant to be used twenty-four hours a day. The new system was immediately tested by “scores of pleased United States residents who formerly wiggled carefully through the ‘hole’ in the barb-wire fence.” But others protested. Congressman Philip Swing from the Imperial Valley howled that the turnstile “virtually nullified the 6 p.m. closing time,” which, he believed, had been rightly established to control Americans “being attracted to Tijuana gambling dens at night.”

The turnstile lasted only three weeks. “Mourners who had been in the habit of ‘making the hole at one’ [a.m.]” watched as the turnstile “was amputated at its base and new strands of wire were stretched across the gap, thereby closing the famous hole in the fence.”

In the next several months, while the Bureau of Animal Industry fought a losing battle against new holes in its fence, San Diegans began to agitate for a liberalized closing time at the border. Collector of Customs William Ellison pointed out that 1,423,751 people had crossed into Tijuana in the first three months of 1931. Clearly, the early closure was not adequate for the busiest port of entry on the U.S. border.

Extended hours finally arrived the following summer when border officials received orders from Washington, D.C., to open the gate until midnight. On Saturday night, July 9, 1932, officials counted about four thousand cars crossing the line to Mexico after 6:00 p.m. Tijuana resorts were packed as San Diegans—for the first time in years—“tasted and sipped of their new privilege—the right to cross the international border line” after dark, untroubled by the late-night prospect of the infamous hole in the fence.

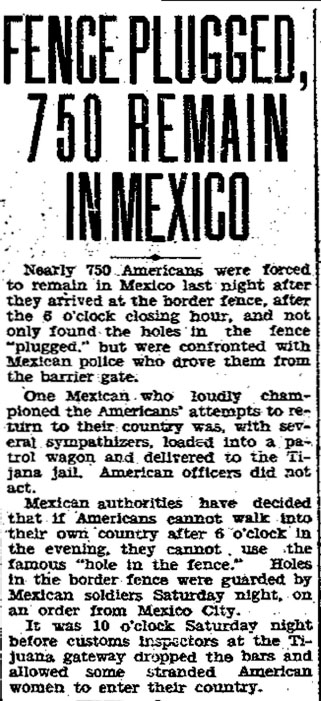

The surprise closing of the celebrated “hole in the fence” stranded hundreds of Americans in Mexico. From the San Diego Evening Tribune, April 6, 1931.

FRANK “BOOZE” BEYER AND TIJUANA

He has been called the greatest benefactor in San Ysidro history—a mining engineer turned rancher who donated land for churches and schools and built the community’s first public library. Dimly remembered today as the namesake of streets and schools, Frank B. Beyer is less known as the “gambler from the owner’s side of the table”—a man with a colorful career below the border who spent his last years giving back his wealth to his adopted community.

Frank Beyer was born in Norristown, Pennsylvania, in 1875. The son of a schoolteacher, Beyer graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and continued his studies at the Missouri School of Mines. As a young mining engineer, Beyer followed mining booms and rushes in Alaska, Colorado and Arizona.

When Beyer reached the booming mining camp of Tonopah, Nevada, in the early 1900s, the mechanics of mining were replaced by other interests. In 1910, the occupation of the thirty-five-year-old Beyer was listed as “roulette dealer” on the U.S. Census rolls. Four years later, the ex-mining engineer discovered his true calling as an entrepreneur of vice in the border town of Mexicali, Mexico.

Beyer partnered with two other Americans—Marvin Allen and Carl Withington—in a Mexicali nightclub called the Owl Café and Theatre. Located just below the border across from the U.S. town of Calexico, the notorious Owl prospered with gambling, liquor sales and prostitution. Mexican authorities welcomed the “ABW Syndicate,” as the three partners were called, and they paid huge shares of the profits to the municipal government as license fees.

Ironically, ABW owed its success to aggressive moral activism in the United States. The Progressive movement in California, which helped shutter San Diego’s notorious Stingaree District in 1912, included the Red Light Abatement Act of 1913, which closed houses of prostitution, declaring them sites of public nuisance. Along with dry laws and codes against gambling, the moral reforms created booming opportunities for “vice tourism” in the wide-open towns below the border, even before the arrival of prohibition in 1920.

Border Baron Frank “Booze” Beyer (center) visiting the racetrack at Tijuana. From San Diego Magazine, September 1967.

The cornerstone property for the Beyer and his fellow “vice-concessionaires” would be the Owl, but their interests also included casinos in the Mexican border towns of Tijuana and Algodones. In Tijuana, the ABW realm controlled the gambling clubs of Monte Carlo, the Tivoli Bar, the Foreign Club and horse racing at the Jockey Club.

In Mexicali, the Owl drew a large share of the American tourists who crossed the border each day in the 1910s. With roulette wheels and nearly forty tables for keno, faro and poker, the casino billed itself as “the largest gambling house on the American continent.” Liquor was served by ten bartenders at “the longest bar in the world.” The Owl also housed the largest brothel on the border, with rooms for more than one hundred prostitutes. Beyer and his partners crafted a slogan to remind tourists that they were open 24/7: “Both night and day, across the way, you will never find closed, the Owl Café.”

But despite profitable success for most of a decade, the Owl did close in 1922 after a severe fire. Rebuilt, it reopened for a time as the ABW Club. But the death of partner Carl Withington in 1925 began the decline of the syndicate’s firm control over vice in Mexicali and Tijuana. New border barons such as James “Sunny Jim” Coffroth and Baron Long moved in to dominate gaming in Tijuana.

In the meantime, Frank Beyer had growing interests closer to his new home in San Ysidro, where he and his wife, Blanche, settled in 1918. In the 1920s, the Beyers ran a jewelry and pawnshop in town. They bought ranch property, bred horses and raised Guernsey cows on a dairy farm Beyer called Rancho Lechuza.

San Ysidro was, of course, conveniently close to Beyer’s business activities in Tijuana. Known to all as “Booze” Beyer, he was a fixture at the racetrack, where he was usually seen in a rumpled gray suit with a black hat crumpled under his arm. He was a skilled card player. Hollywood celebrities were known to drive to Tijuana to play high-stakes faro with Beyer. Evenings were spent at the nearby Sunset Inn—another ABW property—where the music-loving Beyer tipped the orchestra two dollars after every set.

While he kept an attentive eye on his Tijuana gambling interests, Beyer also began to show a public interest in philanthropy. In May 1924, the County of San Diego was surprised to hear that “Booze” Beyer and his wife wanted to donate $7,000 to San Ysidro for a community library. Beyer promised to build and furnish the library and establish a ten-year trust fund to buy books and magazines.

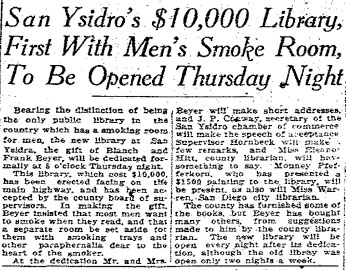

The county gratefully accepted the gift and agreed to honor a few provisos from Beyer. “The conditions,” reported the county librarian, “are that his name will be on the building…that it shall have a smoking room and he wants it understood from the start that there is to be no gambling in the building.” Beyer also requested that copies of the Police Gazette, a racy magazine in the 1920s, be kept available in the reading room. The library added a spittoon for the tobacco-chewing gambler and hung portraits of Beyer and his wife.

The next year, Beyer donated funds to build a Civic Center for San Ysidro on Hall Avenue, between East and West Park. The site would be used by the San Ysidro Women’s Club. In 1927, Beyer gave land and funds for the Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church. Displaying his ecumenical tastes, he also donated money to a local Protestant church.

After a long illness, Frank Beyer died at age fifty-five on November 15, 1931. “He was a splendid character, a square-shooter,” his San Diego banker eulogized. “A gambler—yes, but unlike most gamblers he gave away much of his winnings. He always said, ‘the rich won’t miss the money and the poor need it.’”

Two streets and an elementary school bear the name of Beyer in San Ysidro today. The library that “Booze” Beyer built is now a branch of the San Diego Public Library. While the smoking room is gone and the subscription to the Police Gazette has lapsed, the San Ysidro library still boasts framed portraits of its benefactors, Frank B. and Blanche Beyer.

“Booze” Beyer funded the creation of the San Ysidro Public Library but insisted on a smoking room for men. From the San Diego Union, October 12, 1904.

THE HEIST ON THE DIKE

Employing tactics of Chicago’s gangland, and armed with a machine gun and large caliber automatics, two desperate bandits yesterday noon sent a stream of bullets into the Agua Caliente money car as it crossed the National City dike, killed the two occupants of the machine and escaped with $85,000 in cash and checks.

–San Diego Union, May 21, 1929

“Big time” crime hit San Diego in 1929 with the heist of gambling receipts from Tijuana’s Agua Caliente casino. News of the daring daylight robbery by “machine gun bandits” generated newspaper headlines across the country and enthralled San Diegans for weeks.

The crime occurred midday on Monday, May 20, 1929. A Cadillac coupe from the casino with two Mexican guards was traveling north on old Highway 101, carrying the Sunday revenue to banks in San Diego. Just above National City, on a raised road section called “the dike,” a black Ford touring car without a windshield slipped in behind the money car.

Shooting straight ahead, two men in the Ford stopped the Cadillac by firing bullets into the tires. They jumped out of their auto and blazed away at the money car. The two guards, Nemesio Monroy and Jose Borrego, fought back but died in the gunfire. The killers opened the turtleback trunk, removed bags of cash and checks and then raced north in full view of stunned witnesses on the crowded highway.

The guards had been shot multiple times and their car riddled with bullets. The police immediately declared the crime had the earmarks of the “mob”—possibly Chicago gangsters. The county sheriff reported that a Thompson machine gun had recently been purchased by a resident of Tijuana. The police noted that the killing marked the first use of a machine gun in a San Diego crime.

The suspects’ car was found quickly. In a quiet neighborhood at Edgemont and B Streets, a man mowing his lawn watched as two men in coveralls parked the black Ford across the street. Another car pulled up alongside. The three men transferred several “large bundles which looked like pillows” to the second car and then drove off.

San Diego police found that the Ford was stolen. A cheap coat of black paint had been recently brushed on. But beyond the car and crude physical descriptions of three men, the police knew nothing about the suspects or where they were headed.

The killers were nearby. Marty Colson, twenty-seven, and Lee Cochran, twenty-four, along with a third accomplice, Jerry Kearney, twenty-eight, were hiding at Kearney’s rented house on Villa Terrace near Balboa Park. They had stolen nearly $86,000, but to their shock, all but $5,800 of the money was in checks—nonnegotiable and worthless to them. Kearney and Cochrane burned the checks in the backyard.

Worse, Colson had a severe bullet wound in the shoulder, apparently from return fire from the money car guards. Kearney tried to remove the bullet with a pocketknife, but when his home surgery nicked an artery, his panicked wife called a doctor. Knowing that the doctor would likely file a report with the police, Kearney and Cochran abandoned Colson and left town, leaving Mrs. Kearney to nurse Colson.

Hours later, the police raided the house and captured Colson and Kearney’s wife. Police nabbed Kearney and Cochran two days later in Los Angeles. The suspects were arraigned on May 27 in San Diego, pleading not guilty to charges of murder and robbery. A large crowd milled about the courthouse, excited over rumors that “underworld characters” would attempt to rescue the defendants.

San Diego police officers inspect the bullet-riddled money car. San Diego Police Museum.

But after hearing testimony from the defendants, the police and public fascination over a “gangland” aspect of the heist began to fade. Cochran and Colson admitted to carrying a machine gun, but it was never used. They had killed the guards with .38-caliber handguns. A stolen machine gun and “other artillery” had been dumped into the ocean off San Pedro by Cochran and Kearney after they fled San Diego. There was also no connection to the “mob” or organized crime. The murder defendants were career criminals with long track records of burglary, arson and grand larceny. Kearney—not implicated in the heist itself—was a small-time bootlegger.

Colson and Cochran appeared “eager to get it over with” and pleaded guilty to first-degree murder—apparently to avoid hanging at San Quentin. But as sentencing day approached, Martin Colson attempted suicide by slashing his wrists. He recovered, and then, appearing in Superior Court, he shouldered the blame for the crime, tried to exonerate his partner and begged for a death on the gallows.

On August 6, Judge Charles N. Andrews pronounced sentence on Colson and Cochrane. A moment of drama occurred when the judge addressed Colson: “Yesterday you asked me to sentence you to death. Do you now desire that I impose the death sentence?” Colson was silent at first and then stammered that he left his fate in the hands of the court. The judge “smiled faintly before sentencing him to life imprisonment.” Cochran also received life in prison.

In a separate trial, Jerry Kearney was convicted of being an accessory to the money car robbery and slayings and was sentenced to one year in county jail. His wife, Agnes, never tried in court, was released from jail after a few weeks.

Robert Lee Cochran served twelve years in prison before being paroled. But his partner in the Agua Caliente heist lasted only four years behind bars. Martin Colson, who had once begged for a death sentence, tried repeatedly to escape from Folsom State Prison. His most spectacular attempt was an effort to cross a prison moat by swimming underwater using homemade diving equipment. His apparatus failed and guards pulled him out half drowned.

In July 1933, Colson’s brother, Emil, tried to smuggle guns and ammunition into Folsom, hidden in kegs of nails. The brother was caught and arrested. One year later, Colson made a last, futile attempt to break out using a gun fashioned from prison shop materials. Cornered in the warden’s office, Colson killed himself with his homemade pistol.

THE REVOLUTIONARIES

Deportation, followed by a Mexican firing squad, may be the fate of some or all of the body of potential revolutionists arrested here by United States government agents yesterday…

–San Diego Tribune, August 16, 1926

On a quiet Sunday evening in August 1926, a small army of revolutionaries began to assemble east of Dulzura, just a few miles from the border with Mexico. Led by a charismatic renegade army general, Enrique Estrada, the soldiers were poised to “liberate” Tecate and other border towns, as well as stir up national rebellion against Mexico’s president, Plutarco Calles.

At age thirty-six, General Estrada was already a veteran of many years of revolutionary turmoil in Mexico. The former civil engineering student had turned to soldiering and politics after leaving school in 1910. He achieved success quickly, and by the early 1920s, he had served as governor of his home state of Zacatecas and as secretary of war. But he was on the losing side of a rebellion against President Álvaro Obregón the next year and was forced to flee to the United States.

In Los Angeles, the general began plotting a return to Mexico as the leader of his own army of revolutionaries. With fellow conspirators—including Aurelio Sepulveda, an active general on leave from the Mexican army—Estrada began collecting money and recruiting men to form a private army of insurrectionists.

To equip his soldiers, Estrada contacted San Diego hardware dealer Earle C. Parker to buy rifles, machine guns and ammunition. From his store at 615 Fifth Street, Parker ordered four hundred Springfield rifles, two Marlin machine guns and 150,000 rounds of ammunition. He also ordered four monoplanes from San Diego’s Ryan Airlines, the same company that would later build Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis.

The most fateful purchase was four armored trucks from a Los Angeles garage proprietor. When the local office of the Bureau of Investigation (later known as the Federal Bureau of Investigation) was tipped to a rumor of motor trucks being armored with nickel/steel plate, the agents decided to investigate. They discovered that a Mexican salesman, flush with cash, had ordered the special vehicles, claiming that they would guard gold shipments for a Mexico mining company.

At about the same time, the New York office of the bureau got wind of the large purchase of Springfield rifles from a local supplier. The order led directly to San Diego’s Parker Hardware Company. Along with the evidence that someone was amassing materials for war, the agents learned from Baja informants that Enrique Estrada was actively plotting in Los Angeles.

In early August, the Springfield rifles arrived in Los Angeles and were moved into a warehouse. The bureau put the warehouse under surveillance. Other agents tracked Estrada and his conspirators, and in San Diego, Special Agent Edwin Atherton led a team that scouted the small roads that led to Mexico from San Diego’s backcountry.

On Saturday evening, August 14, Estrada launched his revolution. A small caravan of trucks and cars left Los Angeles and headed south. Federal agents followed closely behind. The caravan stopped for the night in Santa Ana and then slowly drove to Oceanside and inland to Escondido. By late Sunday, they neared San Diego.

The Estrada men kept in touch with one other by telephone. As their caravan lumbered south, a car would occasionally stop for calls to the general, who had gone ahead and was monitoring the progress from a motel room in La Mesa. As soon as they left the phone booth, a federal agent trailing the caravan would pick up the phone and call Edwin Atherton, who was coordinating the Justice Department team from a room at the San Diego Hotel.

As the revolutionaries passed San Diego and headed inland, the agents guessed that the conspirators’ target would be Tecate, with a possible rendezvous point above the border. Atherton’s team quickly drove toward the area. Near Engineer Springs, the agents saw a canvas-covered truck on the side of the road.

The truck turned out to be one of the armor-plated vehicles commissioned in Los Angeles. The agents arrested several Mexicans with the truck and a handful of men hiding in the brush nearby. Within minutes, the rest of Estrada’s army began appearing. Amazed, Atherton’s men easily collected the subdued conspirators as they arrived by car or truck. General Estrada, his personal staff and hardware dealer Earle Parker were soon picked up in La Mesa.

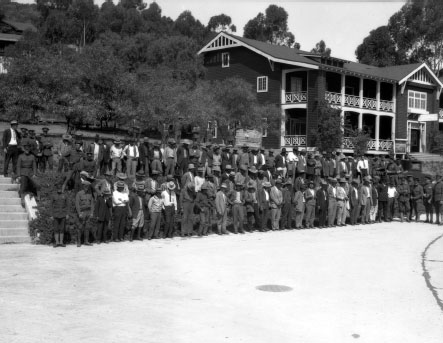

The federal agents had captured 150 men without firing a shot. The revolutionaries were packed into an assortment of vehicles and driven to San Diego. When the county jail was found to be too small for Atherton’s prizes, the convoy continued to Fort Rosecrans, where the prisoners were temporarily housed in barracks. Two days later, Marine Corps guards marched Estrada’s army six miles to the base on Barnett Avenue.

“Death against the wall” was the presumed fate for any of the men deported to Mexico. But there were no extraditions. Estrada and his soldiers were put on the train to Los Angeles in September, where the entire army was indicted in federal court for violating U.S. neutrality laws.

In the trials that followed, Earle Parker was the government’s star witness, providing the details of the conspiracy in return for his freedom. Sixty-two of Estrada’s men pleaded guilty and testified against their former comrades. In February 1927, only Estrada and twelve others were found guilty of crimes. The general received the heaviest sentence: one year and nine months.

With the county jail too small to house General Estrada’s men, the revolutionaries were housed temporarily at Fort Rosecrans. San Diego History Center.

Enrique Estrada served less than one year at the McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary in Puget Sound. After his release, he tried civil engineering for a short time in Los Angeles before returning to Mexico. Remarkably, Estrada decided to reenter public life. He represented Zacatecas for several years as a senator and became director general of Mexico’s national railway. A city in Zacatecas was renamed General Enrique Estrada shortly after his death in 1942.