PART VI

DISORDERLY CONDUCT

A RUINED WOMAN

That man has ruined me. I am ready to die now. I did it because I did not get justice the last time, and I was afraid I wouldn’t get justice this time.

–Bertha Johnson, February 12, 1889

The scandalous story of a “ruined woman” and her shocking revenge captivated San Diegans in the fall of 1889. Bertha Johnson, an emigrant from Sweden, was only twenty-one years old when she arrived in San Diego in October 1888. The young woman took a job waiting tables at the New Carleton Hotel at Third and F Streets. Petite and pretty, she quickly attracted the eye of William Mayne, a boarder at the hotel.

Twenty-nine-year-old Billy Mayne was well known and popular in San Diego. The rising young civil servant had studied law, had worked as a clerk in the tax collector’s and county recorder’s offices and had been a bailiff in Superior Court.

Billy offered to walk Bertha home after work one evening. She said no and then refused to wait on him at the hotel the next day. Billy was persistent. Would she go walking or riding with him? “No, sir,” was her answer. But one night, Billy followed her home. He entered her room and locked the door. Bertha went the window and cried for help. Billy pulled her back. Producing a bottle, he forced a liquid into her mouth, telling her that it “was good for a cough.” Bertha felt weak and “hardly able to move.” Then Billy threw her on the bed and “violated her person.” Afterward, he promised to kill her if she told anyone.

The New Carleton Hotel at Third and F Streets. San Diego History Center.

Another encounter came one month later. But this time Billy swore to Bertha—“on her little Swedish Bible”—that he would marry her. By June, Bertha realized that she was pregnant. For this predicament, Billy had an answer. Bertha needed to take the steamer to Tacoma, he said. He would follow on the next boat, and they would marry, just as soon as he could borrow some money from a friend.

Billy also gave her a bottle of medicine that “would relieve her of her trouble.” He instructed her to go to a lodging house in Tacoma and register under an assumed name. He insisted that she go right to bed when she got there and drink the medicine immediately. It would not taste good, he warned, but she needed to drink half the bottle, and under no circumstances should she call a doctor, “no matter how badly she might feel.”

The next day, Bertha summoned her courage, but instead of buying a steamer ticket, she paid a visit to the justice of the peace, William A. Sloane, who recorded her criminal complaint, alleging that William Mayne “did under promise of marriage seduce and have sexual intercourse with Bertha Johnson, an unmarried female of previous chaste character.”

The case remained under wraps until mid-October, when the county grand jury announced the indictment of William Mayne for “intent to procure abortion.” A second indictment soon followed, adding a charge of attempted murder by “administering carbolic acid.” Evidently, the jury understood what Bertha Palmer had missed: the “medicine” Billy had given her was useful in diluted form as an antibiotic. Swallowed full-strength, it was lethal.

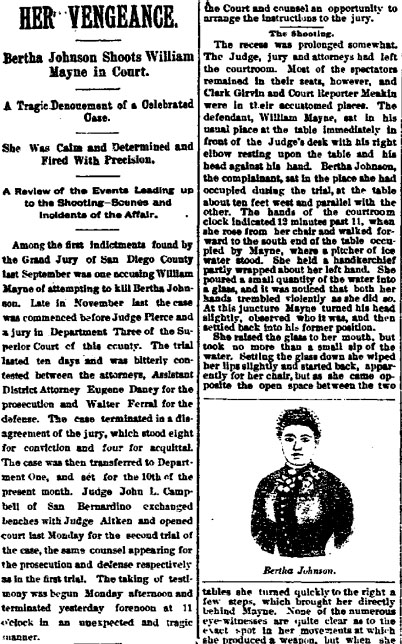

Trial began in Superior Court in November. Bertha Johnson spent two difficult days on the witness stand, breaking down in tears several times. “The girl is of foreign extraction and does not easily understand the questions asked,” the San Diego Union explained, adding that the witness told a tragic story of “atrocious character” with details “unfit for publication.”

When Billy Mayne took the stand, he admitted that he had sexual intercourse with Bertha Johnson several times but claimed that he had never used force. “Everything the girl swore on the stand is false. I never promised to marry her and never gave her carbolic acid.”

Arguing for the prosecution, Assistant District Attorney Eugene Daney held the court in “almost breathless silence” as he described how “a simple, unsophisticated young girl” had begged Billy Mayne to save her from a life of shame. Instead, Mayne had created a nearly foolproof scenario: “An unknown girl lands in a strange city. She is found dead the next morning with a bottle half full of a 95% solution of carbolic acid beside her—a clear case of suicide and a burial in an unmarked grave.”

The twelve male jurors considered the evidence for nearly three days. When their final ballot showed eight for conviction and four for acquittal, the judge released the jury and dismissed the case. The prosecutors would try again. In February 1890, with Judge John L. Campbell from San Bernardino County presiding, Bertha Johnson again took the witness stand. The Union noted the witness “is a slender girl, below average in height, with light hair and blue eyes.” The reporter chose not to record that Bertha Johnson was now some eight months pregnant.

At midmorning on the third day of testimony, as the court settled in after a short recess, Bertha Johnson rose from her chair and walked over to the defense table, where she poured herself a glass of water from a pitcher that sat near Billy Mayne. She took a sip, started to walk away and then turned suddenly in Mayne’s direction.

Aiming a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson pistol at Mayne’s head, she fired three shots at near point-blank range. Mayne slumped to the floor after one bullet penetrated his neck. A newspaper reporter grabbed Johnson’s arms, and the pistol fell to the floor.

The next morning, with the courtroom “jammed full of morbidly curious people,” Judge Campbell handed the case to the jurors. Eleven hours later, they returned to report a deadlock. Once again, the case was dismissed.

From the San Diego Union, February 13, 1890.

Billy Mayne recovered from his injury and moved to Baker, Oregon, where the 1900 federal census listed his occupation as “gambler.” He married and then moved to Visalia, where he died in 1921. The fate of Bertha Johnson remains a mystery.

DEATH OF THE BUTTERFLY DANCER

A shocking mystery grabbed the attention of newspaper readers on Tuesday morning, January 16, 1923. “YOUNG WOMAN’S BODY FOUND ON BEACH,” the San Diego Union headlined. “BODY OF PRETTY YOUNG WOMAN CAST UP ON THE WAVES” was the San Diego Sun’s lurid story.

A family picnicking on the beach at Torrey Pines had stumbled across a body as it lay partially covered in the sand. Barely clad in silk undergarments, the woman lay parallel to the water’s edge and appeared to have drowned. Several yards down the beach, a small suitcase was found with odd clothes. Had this been an accident? Was it possibly suicide or even murder?

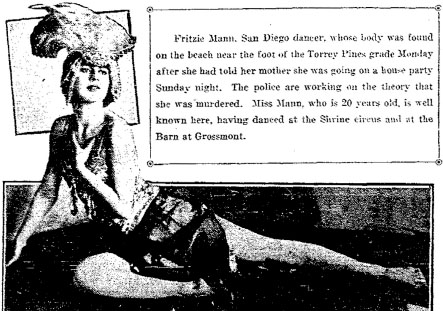

Police detectives identified the victim as twenty-year-old Frieda Mann, a dancer who had moved to San Diego two years before with her mother, brother and sister. The attractive “butterfly dancer” had performed solo in Los Angeles and locally and was reportedly under contract with the motion picture company Famous Players.

Mrs. Amelia Mann told police that her daughter, known as “Fritzie,” had left home on Sunday afternoon. Carrying a suitcase, she had last been seen boarding a streetcar on her way to a house party in Del Mar. One hour later, Fritzie called her mother to tell her that the party would actually be at a house in La Jolla.

A postmortem examination revealed that Fritzie had indeed drowned. Her lungs were full of water but not sand, which an ocean accident might have indicated. Autopsy surgeon Dr. John J. Shea noted two other significant details. The victim bore a severe bruise above her right eye that had been inflicted before her death. Shea also noted that the dancer “was in a delicate condition.” The police followed up the latter revelation by questioning “men who had been friendly with her” in recent months.

One apparently friendly contact was thirty-year-old physician Dr. Louis L. Jacobs, an army captain stationed at Camp Kearny. Upon hearing of Fritzie’s death, Dr. Jacobs voluntarily approached the police and said that he knew the girl well. Jacobs claimed that Fritzie had been secretly married to a “motion-picture man.” The doctor added that he had tried to help her get an abortion in Los Angeles but that she had backed out of the procedure. The police thanked the doctor for his information and then arrested him.

The mysterious death of young Fritzie Mann intrigued San Diegans. From the San Diego Union, January 17, 1923.

That Friday, January 19, San Diego newspapers announced the discovery of a “love cottage” in La Jolla. A girl fitting the description of Fritzie Mann had been seen in the company of a man believed to be a Hollywood movie director named Rogers Clark. The couple had registered as “Alvin Johnson and wife, L.A.” at the Blue Sea Cottages at the foot of Bon Air Avenue. When shown a photograph of Clark, the motel’s manager, Albert E. Kern, told police that the image bore “a remarkable resemblance” to the man he had rented a cottage to on Sunday night.

Clark was arrested in Los Angeles and hurriedly brought to San Diego by train. The director admitted knowing Fritzie Mann but claimed that he had not seen her for many weeks. After questioning, the police released Clark and announced that he had fully accounted for his whereabouts on Sunday, January 14.

With the release of Clark, suspicion returned to Dr. Jacobs, still in custody after his arrest earlier in the week. The police brought Jacobs to the Blue Sea Cottages to confront Albert Kern. The proprietor nervously acknowledged a “resemblance” to the man he had seen accompanying Fritzie Mann. Jacobs was released on writ of habeas corpus, but an indictment soon followed from the county grand jury. Held without bail in the county jail, Dr. Jacobs would now stand trial for the alleged murder of Fritzie Mann.

The sensational case drew national attention, with newspaper coverage in Chicago and New York City. The Los Angeles Times noted that spectators waited for hours to claim a seat in the courtroom. Others carted their own chairs to the courtroom or stood in the aisles jammed with people.

When trial began in Superior Court in late March, the prosecution argued that Fritzie Mann had either been killed or rendered unconscious before being carried to the beach. Dr. Jacob’s defense team replied that with an official cause of death by drowning, there was no murder and suggested that Miss Mann had probably committed suicide.

The most effective prosecution witness appeared to be handwriting expert Milton Carlson from Los Angeles. Carlson testified that the handwriting in the motel register was identical to the writing in letters from Dr. Jacobs’s own hand. Other witnesses challenged the defense theory of suicide, declaring that Miss Mann was always in “the best of spirits.”

The case went to the jury on April 15. After thirty-five hours of deliberation, the jurors reported that they were “hopelessly deadlocked.” Judge Spencer Marsh thanked the jurors for their service and then dismissed them. Louis Jacobs folded his hands across his chest and grinned at his attorneys. The smile faded when District Attorney Chester Kempley immediately requested a new trial.

Two months later, it began again. Familiar evidence was displayed, and testimony was recounted. But the prosecution “uncorked a sensation” when a nurse who once worked with Dr. Jacobs at Camp Kearny testified that she had seen the doctor driving from La Jolla to the hospital late on the fateful Sunday night. But another prosecution witness backfired badly when Blue Sea Cottages manager Albert Kern declared that he was now certain that Dr. Jacobs was not the man he had seen with Fritzie Mann.

On Monday morning, July 21, with one day of deliberation, the jury announced a verdict of “not guilty.” After nearly six months in jail, Louis Jacobs, “wearing a smile of relief and elation,” walked from the courtroom a free man. “I want to forget all this terrible business,” the doctor told reporters. “I like to think it has been only a dream.”

THE ROYAL COACH AFFAIR

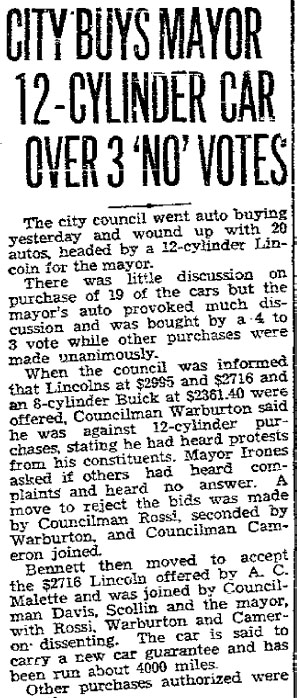

The city council went auto buying yesterday and wound up with 20 autos, headed by a 12-cylinder Lincoln for the mayor. There was little discussion on purchase of 19 of the cars but the mayor’s auto provoked much discussion.

–San Diego Union, November 21, 1934

Lasting only six months, the mayoral term of Dr. Rutherford B. Irones was one of the shortest in San Diego history. It was certainly the strangest.

Irones was appointed mayor on August 2, 1934, replacing former mayor John F. Forward Jr., who had resigned with poor health. The fifty-seven-year-old Irones was a respected physician and World War I veteran. He was best known as the director of the local chapter of the Crusaders, a militant anti-prohibition organization.

Mayor Irones got off to a rough start. His first paycheck—about $100—was garnished to partially satisfy an old debt of $648. Irones recovered from the embarrassment and launched a public safe driving campaign to combat the “staggering” number of automobile accidents in the county. Pointing out that San Diego had “one of the highest casualty ratings in the nation,” Irones urged the police to enforce “strict observance of traffic regulations.”

In October, Irones decided to test his clout by investigating San Diego’s Civil Service Commission. The commissioners supervised the appointments of more than one thousand government workers. Control of the commission meant power over the appointments. Vowing that he would “clean house from bowsprit to aft rail,” the mayor demanded the resignation of every member of the commission. The plan failed when he could not secure a majority of council votes.

Irones found his next campaign more successful. He determined that he needed an official automobile. The council agreed and offered him a small eight-cylinder car. Irones countered with his own specifications: “a machine of at least 150-horsepower, with a 7-passenger body” and a “12-cylinder engine of the V-type.”

On November 21, Mayor Irones took delivery of a twelve-cylinder Lincoln that cost the taxpayers $2,716. The public immediately mocked the extravagant purchase. “People are in breadlines,” a letter to city council pointed out, adding that “a flivver is good enough for anyone.” The newspapers named the oversized black sedan the “Royal Coach.”

Soon to be dubbed the “Royal Coach,” the city purchase of a twelve-cylinder Lincoln for the mayor “provoked much discussion.” From the San Diego Union, November 21, 1934.

Irones enjoyed his Lincoln for only three days. Late Friday afternoon, the mayor and his wife went out for a drive. Moments after leaving their Torrance Street home in Mission Hills, the mayor sideswiped a car as he raced up Reynard Way. The other car was knocked to the side of the road and overturned, badly injuring George and Mildred Pickett. The Royal Coach paused momentarily, then sped up and disappeared.

Two police radio prowl cars were quickly at the scene. As Mr. and Mrs. Pickett were being taken to Mercy Hospital, a young boy told the police that he had just been at the mayor’s house and had seen a damaged black sedan. Patrolmen Nickel and Logan drove to the house and found the mayor walking around his official vehicle, muttering about a car that had forced him over on the wrong side of the road. “He seemed to be drunk,” the police report read. “The smell of liquor was very strong on the mayor’s breath and his speech was incoherent.”

The mayor failed to report to work the following Monday. While he recovered in bed from “a concussion and hemorrhage,” his wife fended off newsmen. “Although uninjured, she said today ‘she dislikes so to make all these explanations,’” reported the Los Angeles Times.

Irones’s alleged drunken hit and run was ignored by the police. Beyond release of the police report to the newspapers, Chief George Sears refused to comment on the incident. The city council seemed unconcerned, as well, though members did worry about who would pay for the estimated $300 in repairs to the Royal Coach. But many San Diegans were incensed by the affair. Several women’s organizations, led by the influential Thursday Club, demanded the mayor’s resignation for his “detrimental” conduct, which they found “particularly injurious” to the coming exposition planned for Balboa Park.

On December 22, Mayor Irones was arrested on a felony criminal complaint of leaving the scene of an accident and failing to render aid to the accident victims. The case went to trial in Superior Court in late January. A jury of ten women and two men listened to a parade of witnesses who had seen the mayor’s speeding sedan strike another car.

The four-day trial ended on February 1. The jury returned a verdict in twenty-two minutes, convicting Irones of hit-and-run driving. Two weeks later, Judge G.K. Scovell sentenced the mayor to one year in the county jail. “I’ll take it on the chin like a man,” Irones declared. “I’m sure I haven’t lost any friends…those I just thought were friends don’t count.”

The ex-mayor served six months and was released after agreeing to pay the hospital bills of Mr. and Mrs. Pickett. The couple later won a civil suit and collected $20,000 in damages from Irones and $10,000 from the Ford Motor Company.

The disgraced mayor, Dr. Rutherford Irones, leaving court after sentencing, February 10, 1935. San Diego History Center.

The doctor resumed his medical practice in San Diego, but his troubles continued. His wife, Essy, left him in 1937. Two years later, he was arrested for stabbing his twenty-eight-year-old girlfriend. Charges were dropped when the jury failed to reach a verdict. A conviction for assaulting a hotel owner cost him two months in jail in 1940. He died without survivors on February 13, 1948, at the Sawtelle Veterans Home in Los Angeles.

THE BRIBE

San Diego is the rottenest graft ridden city of its size on the American continent. If the Mayor and the Chief of Police don’t know it they ought to be sent to a home for the feeble-minded. If they do know it, they both should be in the penitentiary.

–Abe Sauer, publisher, San Diego Herald

The muckraking editor and publisher of the San Diego Herald was never one to mince words. A self-proclaimed expert in “the gentle art of truth telling,” Abe Sauer frequently used his weekly newspaper to assault in print the political high and mighty of San Diego.

Occasionally, Sauer’s attacks appeared to go too far. In a front-page editorial that he published on May 21, 1925, Sauer accused three city councilmen—Don Stewart, Virgil Bruschi and Harry Weitzel—of violating prohibition laws, protecting downtown gambling and prostitution and other unnamed crimes. The graft-ridden misdeeds of the “councilmanic combine” required immediate grand jury attention, Sauer said. He was particularly scornful of Councilman Weitzel, describing him as “the kind of man who gets his fingers full of splinters from scratching his head.”

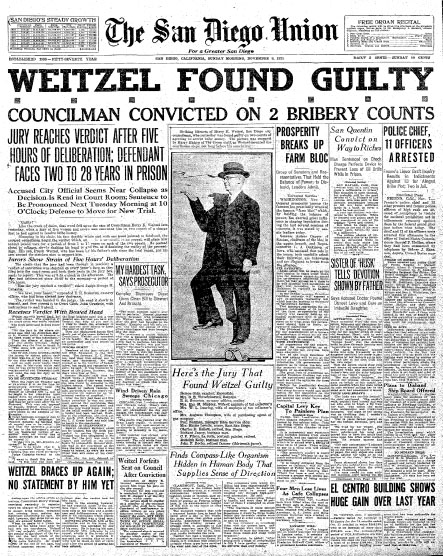

Sauer’s blast drew a quick summons to testify before the county grand jury. While the newspapers speculated over the salacious details the Herald editor might be providing, the results of the grand jury probe surprised everyone. On July 7, the jury announced the indictment of Councilman Harry Weitzel on two counts of bribery. Charged with “agreeing to accept” money for his vote on two important local issues, Weitzel would be the first San Diego councilmen to go to trial for allegedly betraying the public trust.

Abe Sauer may have felt vindicated by the indictment, but like many San Diegans, he was cynical of the expected outcome, declaring, “We cannot question his guilt—we cannot hope for his conviction.” Sauer questioned the fairness of the presiding judge in the case, George H. Cabaniss: “This judge comes from San Francisco, where graft is a pastime indulged in by everyone—bankers, preachers, politicians, and about everyone else.”

When respected businessman Ed Fletcher accused a city councilman of soliciting a bribe, a court indictment and public scandal followed. Special Collections, University of California–San Diego.

When the case began in Superior Court on October 29, 1925, the star witness was not the colorful Abe Sauer but the rather less flamboyant businessman Ed Fletcher. In the previous year, Fletcher had been negotiating the possible sale of his coveted Cuyamaca Water Company to the City of San Diego. The asking price was $1.4 million. But as Fletcher revealed in court, at least one city councilmen wanted in on the deal.

“Councilman Harry K. Weitzel came to my office on Eighth Street on the morning of June 22 [1924], and asked for a private interview,” Fletcher testified. The two men then walked across the street to the lawn of the San Diego Public Library, where Weitzel told Fletcher that “he wanted $100,000 in advance and in consideration of that amount would dveliver his vote and that of Councilmen Stewart and Bruschi.”

Instead of rejecting the offer, Fletcher suggested a conference with his business partner, banker Charles F. Stern. The meeting took place the following Sunday at Stern’s office in Los Angeles. Weitzel repeated his demand, adding that he wanted an additional $4,000 to secure his vote on another council issue: the proposed annexation of East San Diego. As the three men discussed the possible arrangements, Fletcher’s secretary hid in a storeroom adjoining the office, taking copious stenographic notes of the conversation.

When Stern followed Fletcher to the witness stand, he corroborated his partner’s testimony in every detail. “Neither Ed Fletcher nor myself, singly or together, ever agreed with Weitzel at that time or any time to pay him a bribe,” Stern declared.

A pensive Harry Weitzel sits in court between his brother Frank (left) and his attorney. San Diego History Center.

Councilmen Stewart and Bruschi were also called to testify. Both claimed that they had never discussed money for votes with Weitzel. On the last day of testimony, Councilman Weitzel took the stand and denied everything. “Nothing whatever was said in the conversation between Fletcher and me regarding a demand for $100,000,” Weitzel declared, adding with dramatic fervor, “When he testified on the stand that I asked for money, he perjured his soul to hell!”

The jury of five women and seven men took the case on Saturday morning, November 7. After deliberating for five hours, they returned to court with a verdict of guilty. “Slumping in his chair, his face deathly white,” Weitzel seemed about to collapse, reported the San Diego Union. His son, Frank Weitzel, who had been by his father’s side throughout the trial, “put his arms around the stricken man to support him.”

In the wake of the trial, the proposed sale of the Cuyamaca Water Company to San Diego was killed. Fletcher sold the system the next year to the La Mesa, Lemon Grove and Spring Valley Irrigation District (today’s Helix Water District) for $1.1 million.

The conviction of Councilman Harry Weitzel for bribery headlined the morning newspapers on November 8, 1925. From the San Diego Union.

In September 1926, the district court of appeal reversed Weitzel’s conviction, deciding it was not a crime for a city councilman to merely offer a bribe and became a crime only when someone agreed to the bribe. A criminal offense required a “meeting of the minds.” The State Supreme Court confirmed the ruling on April 22, 1927, saying that there was “no offense in soliciting bribes unless some other person agrees to pay him the bribe.”

Free but disgraced, Harry Weitzel spent his remaining years running a small neighborhood grocery store at 1209 Lincoln Avenue. He died of a stroke at age sixty-five on February 12, 1932. His obituary in the Union did not mention his legal troubles but did note that he had been in failing health ever since his retirement from the city council in 1925.

DRAGSTERS ON THE BOULEVARD

The drag street riot on El Cajon Boulevard is symptomatic of the disrespect for authority so pronounced in some areas of our society. Those who riot or endanger the public safety to enforce their demands on government and law-abiding citizens cannot be tolerated…San Diego must not be intimidated.

–editorial, San Diego Union, August 23, 1960

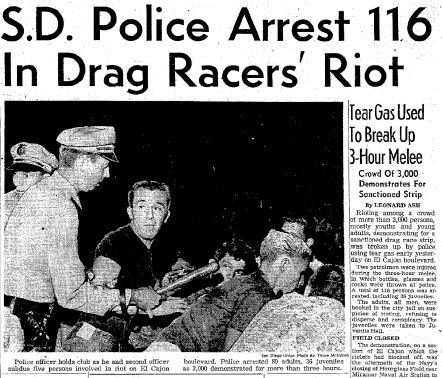

It began as a mass demonstration on El Cajon Boulevard near Cherokee Avenue. Young car racing enthusiasts gathered to protest the lack of a legal drag strip in San Diego. When the protest turned into street racing, the police moved in with tear gas and batons. More than one hundred people were arrested in the bedlam that followed, known thereafter as the “El Cajon Boulevard Riot.”

Drag strip racing had been growing in popularity for many years. By 1959, there were an estimated two hundred drag strips in the United States. In San Diego, racers used “the country’s oldest official drag-race course”—a retired airstrip on Paradise Mesa east of National City. Construction of a new housing development closed the Paradise track in 1959.

With no official drag strips available, San Diego hot rodders used an old navy airfield near the Miramar Naval Air Station called “Hourglass Field.” Automobile races sponsored by the California Sports Car Club were held on a 1.8-mile-long track. Unsponsored drag racing also took place, while the navy turned a blind eye. But when a racing accident hurt four people on August 6, 1960, the navy closed the field.

Local car clubs lobbied city and county officials for an official site for drag racing. San Diego police chief A.E. Jansen was unsympathetic, claiming that “drag strips actually stimulate highway recklessness among those viewing such contests.” But one car club member cautioned, “If we don’t get the strip, cars will be dragging in the streets.” The warning would prove prophetic.

In mid-August, mimeographed flyers began appearing in movie drive-ins, coffee shops and car clubs announcing a “mass protest meeting” on El Cajon Boulevard, set for 1:00 a.m. on Sunday, August 21. A local disc jockey, Dick Boynton of KDEO, spread the news to radio listeners. Soon after midnight on Sunday morning, hundreds of teenagers and young adults began gathering along the boulevard.

At about 1:00 a.m. some members of the crowd blocked off the street and began racing. Between Thirty-fifth and Fortieth Streets, “cars, of all models and shapes, raced two abreast,” reported the Union. “Thousands of spectators lined the sidewalk and center island, leaving almost no room for the cars to pass.”

More than sixty-five policemen moved in at about 2:00 a.m. and ordered the demonstrators to disperse. Throwing tear gas grenades at the feet of the spectators, they waded into the crowd with their riot sticks. “Almost everyone was running toward their cars,” recalled a witness. “Other people were on the ground, unable to run because of the tear gas.”

About one hundred demonstrators stood their ground at a service station lot and “threw a barrage of soft drink bottles and rocks at the police.” Three young men found their way into the Coca Cola bottling plant at Thirty-eighth Street. They broke open cases of Coke and began heaving glass bottles over a fence at the police.

It took three hours to quell the “mob,” estimated to be three thousand people according to the Los Angeles Times. Two policemen were hurt, and others had their uniforms torn. A few officers lost their guns in the melee. Eighty adult demonstrators and thirty-six juveniles were arrested. The adult suspects were loaded into vehicles and driven to the city jail at 801 West Market Street, where they were booked, photographed, fingerprinted and placed in cells. The juvenile suspects were referred to the County Probation Department.

For the ID technicians in the Police Records Bureau, it was quite a night. In the early hours of Monday morning, the two techs on duty were suddenly swamped with fingerprint cards that had to be checked for warrants or prior arrests through huge index name files, then classified using the FBI-approved system and, finally, searched individually in numerous drawers crammed with thousands of fingerprint cards from previous years.

From the San Diego Union, August 22, 1960.

Police filling a van with people arrested on El Cajon Boulevard. San Diego History Center.

Monday night brought new unrest and more fingerprint cards for the harried ID techs. Cruising in caravans in San Diego and the city of El Cajon, drag racers taunted police with games of “motorized tag.” Another one hundred people were arrested. Some were charged with disorderly conduct, others with weapons charges. More than thirty juveniles were picked up for curfew violation.

On Wednesday, the twenty-fourth, the police arrested a printer named Herbert Sturdyvin, age twenty, on suspicion of conspiracy in the printing and distribution of the mimeographed flyers police blamed for the mass demonstration on Sunday. Sturdyvin was released without bail and never charged. The following weekend, San Diego police braced for new disorder rumored to be stirred from sympathizers coming from Los Angeles. The demonstrations failed to materialize.

In the wake of the riot, new demands were heard in the community for an authorized drag strip. The San Diego City Council promised to appoint a committee to “study the possibilities.” The president of the National Hot Rod Association pledged help from his organization in getting an official strip but insisted that local enthusiasts would have to “reform” their conduct.

Municipal court judges dismissed most of the cases of the rioting teenagers in the following weeks. Charges of police brutality enlivened some of the court hearings. Radio DJ Dick Boynton testified that people had been struck in the head by tear gas grenades and that young teenagers were clubbed by policemen. The department vigorously denied the charges.

Eventually, the campaign for a drag strip was rewarded. The San Diego Raceway opened in Ramona in 1963 and operated for several years until it became a runway for the Ramona Airport. Carlsbad Raceway opened in 1964 and hosted drag racing until the track closed in 2004.