PART VII

FEAR AND INTOLERANCE

THE STUDENT STRIKE

The ruling members of the board of education are not wanted in their places anymore. The people of San Diego are not only tired of their petty politics, but disgusted with the result. The thing for those members is to slide quietly out, resign, quit. It will save a lot of trouble and expense for them to do it as quickly as possible.

–San Diego Union, June 7, 1918

Politics and education mixed poorly in the spring of 1918 when the San Diego Board of Education abruptly fired nineteen teachers at San Diego High School. The action led to a mass walkout of students from the school and local newspaper headlines that rivaled news of the war in Europe.

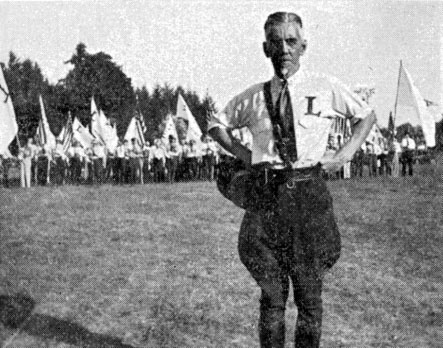

San Diego’s school superintendent that year was Duncan MacKinnon. The thirty-three-year-old, Canadian-born educator was respected and popular among students and faculty. He enjoyed considerable autonomy in the administration of the city school system. But many in the community were uncomfortable with the unmarried professor who smoked cigars in public and enjoyed dining in restaurants that served wine—this on the eve of national prohibition.

MacKinnon’s tenure was threatened in April 1917 with election of three new people to the five-member board of education. The “solid three”—L.G. Jones, John Urquhart and Laura Johns—decided to curtail the superintendent’s responsibilities and adopt for themselves unprecedented personal involvement in San Diego education. The new board began by sending a questionnaire to all teachers, requesting their opinions on their jobs and stating that the recent “vote of the people indicated that certain changes in the schools” had become necessary. To the teachers, who served without tenure under one-year contracts, the questionnaire appeared threatening—almost like a loyalty oath to the board; 91 out of 94 teachers met to discuss the unusual questionnaire. They agreed to not reply individually but rather to send a collective response to the board, which included a request that the practice of tenure be considered for qualified teachers.

San Diego school superintendent Duncan MacKinnon. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

The summer passed quietly, but in the fall, the board announced that Duncan MacKinnon’s term as superintendent would expire at the end of the school year. The action was immediately denounced in the community. When the board announced the imminent hiring of a new superintendent, MacKinnon quietly resigned.

Next, the board decided to limit the authority of San Diego High’s principal, Arthur Gould. The principal was asked to turn in his keys to the school custodian. Board members began sitting in classrooms with pencil and notebook to monitor teachers, and the editor of the student newspaper began fielding unwanted editorial advice from the board.

As the school year neared a close, the board took a critical step, posting on June 3 “a notice to be sent to teachers whose services would not be required for the ensuing school year 1918–19.” The list named nineteen teachers, including Principal Gould. Reasons for the dismissals were not offered, although the teachers were all known “friends of MacKinnon” and each had signed the collective response to the board questionnaire the previous year.

To protest the abrupt firing of several teachers, the student body of San Diego High School marched through downtown to demand satisfaction from the school board. Special Collections, University of California–San Diego.

The next day, a boisterous assembly of 1,800 students met in the City Stadium (Balboa) to consider action. They approved a resolution vowing to leave school and not return until the board explained the firing of the teachers. The students decided to present their resolution to the board in person. After a quick telephone call to the chief of police requesting permission to stage a parade, the students gathered in front of the school, and then, led by their senior class president, nearly the entire student body marched nine blocks through downtown to the school board offices at the Southern Title Building on Third Street.

After handing their resolution to an embarrassed secretary, the students marched back to school, picked up their books and went home. On the following Monday, twelve students showed up for class. All the teachers faithfully reported for work but for the remainder of the school year, classrooms were empty.

For the next three weeks, the student strike was headline news for San Diego’s newspapers. Abe Sauer, the sharp-tongued editor of the weekly Herald, joined the Union in calling for the recall of the school board’s “blundering incompetents,” writing in an editorial that “their asinine work is becoming a public menace.” Civic and business leaders joined the condemnation. A Citizens’ Recall Committee of prominent San Diegans met with an attorney to plan recall proceedings against the board members.

The drama ratcheted higher on Sunday, June 16, when the Union carried a one-fourth-page paid notice from the school board. Addressed to “the Parents and Students,” the notice stated the board’s intention to “not in any manner recognize the insurrection and the alleged resolution of the so-called student body of the High School” and emphasized that “each and every student” would be expected in the classroom on Monday morning. But the strike continued, and a school holiday was declared for the remainder of the term.

On June 22, the Union published a letter from the board meant to clarify its current position. The letter began by noting that there would be no dialogue with the teachers regarding their dismissals. It ended with a stunner:

At the time the order was made dropping certain teachers we were informed that several among those dropped were under surveillance by the authorities for Pro-Germanism and these teachers were dropped for that reason.

The letter was quickly reviewed by the Recall Committee, which then contacted the Justice Department and the U.S. Army. Government officials assured the committee that no teacher had been investigated for disloyalty.

San Diego High School began its fall semester on August 31 with a new principal and a new school superintendent. A few of the teachers had been reinstated, but most had found jobs elsewhere. A recall election was finally held on December 3. By a vote of more than three to one, the “solid three” were turned out of office.

THE YOUNG COMMUNISTS

“You can’t parade. Our orders are to prevent it.” In a moment there was a seething, screaming mass around the policemen. Staves and sticks began to fly.

–San Diego Sun, May 31, 1933

On May 29, 1933, San Diego’s city manager, Albert Goeddel, publicly warned that there was a grave possibility of a major riot in the city streets. Scores of Communist youths and radical agitators were about to descend on the city, the manager claimed, with plans to disrupt a Memorial Day parade in downtown San Diego. But Goeddel was reassuring: “The police are ready for them.”

Hints of trouble had begun days earlier when “National Youth Day” organizers requested permission to hold a parade. By a four to three vote, the city council refused to issue a permit when the students declined to promise that their rally would have no “red flags.” Unperturbed, the group told the council that they would probably march anyway.

San Diego’s Memorial Day parade was scheduled to begin at 10:00 a.m. on Tuesday, May 30. Serving soldiers from all military branches, veterans groups, Boy Scouts and high school military cadets, all planned to march from downtown to Balboa Park for patriotic services at the Spreckels Organ Pavilion. Automobiles would follow carrying Civil War veterans.

But the newspapers seemed most interested in reporting that several truckloads of “radicals” had arrived early that morning from Los Angeles. Singing the “Internationale,” a crowd assembled at New Town Park at Columbia and F Streets (today’s Pantoja Park). Several speakers—led by known “Reds” from Los Angeles Jack Olsen, twenty-two, and Jean Rand, twenty-six—took turns denouncing American imperialism and the capitalist system. President Roosevelt was attacked as a “Wall Street president” and a leader of the “boss class.”

According to reporting by the San Diego Union, “the Communists” appeared to be mostly “children, aliens and unfortunates headed by and herded by a handful of determined organizers.” Many carried banners: “All War Funds for Unemployed,” “Roosevelt’s New Deal: Hunger and War” and “No Curtailment of Education.”

Watching the rally from the park perimeter, uniformed police and several plainclothes men seemed most offended by the banners. Sergeant Charles Glick, a burly marine, pointed out particular banners that he didn’t like to a reporter for the Sun. “If those birds start any trouble, I’m going after those and start a collection.”

After speeches and songs, Olsen suggested a march to Sixth and A Streets for a second rally at the First Congregational Church. Grabbing the banners, the crowd formed in ranks and began marching to the edge of the park. “Well, that’s that!” murmured a policeman. About thirty officers barred the path and then surged into the demonstrators to grab their banners.

For fifteen minutes, the police and demonstrators pummeled one another in Pantoja Park. San Diego Police Museum.

Sticks pulled from the banners and staves yanked from park benches quickly became weapons for the demonstrators. For fifteen minutes, the police and demonstrators pummeled one another. The “Communists,” a reporter observed, appeared to have the upper hand by the “sheer weight of their numbers.” The tide turned when the police fired tear gas into the crowd.

Nine policemen were injured and sent to the hospital. The Union estimated that about thirty rioters had been hurt but none was hospitalized. Instead, “they were loaded into trucks by their fellow Communists and returned to Los Angeles without stopping for treatment.” A dozen motorcycle patrolmen escorted the trucks to the county line at Del Mar.

Nine arrests had been made, six for misdemeanor inciting a riot. Three men were booked at the city jail for felony assault with a deadly weapon. Reports of “third degree methods” employed at the jail circulated about town, but all the demonstrators were soon released on bail.

The next morning, editorials in San Diego’s rival newspapers—the Union and Sun—dueled over the causes of the violent brawl in the park. The Union “thoroughly approved” of the city council’s decision to deny approval of a “red-flag parade” but admitted that “there could have been more intelligent handling” of the affair.

The Sun was less understanding. “The disgraceful riot could have been prevented by the city council,” the newspaper declared. “Had the agitators been permitted to march peacefully,” nothing would have happened. “Fanatical as they may be with respect to the best way of curing our social ills, these young men and women [had] the right to convene and parade.”

The following week, a defensive city council sat in session and listened to a barrage of complaints from San Diegans alleging “police brutality and councilmanic intolerance.” A letter read by respected businessman George W. Marston tried to strike a conciliatory tone: “We are actuated more by desire to prevent its repetition than to censure any person or group.” But Marston left no doubt that he believed the councilmen were culpable, saying that it was unwise and discriminatory to refuse the parade permit. Regarding the actions of the police, Marston added, “Disinterested witnesses testify that the police, led by a sergeant of marines, charged the crowd without warning…striking indiscriminately and precipitating the violent struggle that followed.”

In June, three demonstrators charged with attacking police officers went on trial. Contradictory eyewitness testimony bewildered the jury. Defense attorneys charged that the council’s refusal to issue a parade permit had amounted to entrapment and that the police action had been “a deliberate and shameful frame-up.”

Only one demonstrator was convicted. Frank Young, a young black man from Los Angeles, was found guilty of assaulting two policemen and given the maximum sentence of six months in jail. The leaders of the rally in New Town Park, Jack Olsen and Jean Rand, escaped prosecution, although both would appear frequently in Los Angeles newspapers in coming months for disturbing the peace in radical demonstrations.

THE SILVER SHIRTS

There unquestionably is a concerted move on the part of un-American and radical groups to bring about the overthrow of the United States government. We have endeavored to get to the bottom of all such moves.

–Congressman Charles Kramer, August 5, 1934

In the summer of 1934, a Special Committee on Un-American Activities opened hearings in Los Angeles. Chaired by Representative Charles Kramer, the committee was following reports of “alarming proportions” that armed radicals called “Silver Shirts” were drilling in San Diego and preparing for revolution.

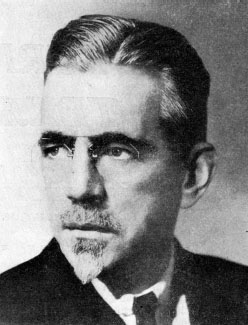

The Silver Shirts were part of a nationwide movement of anti-Communists led by right-wing activist William Dudley Pelley. Founded as the Silver Legion of America on January 31, 1934, Pelley claimed that his group would prepare “a great horde of men nationally to meet the [Communist] crisis intelligently and constructively.”

Pelley greatly admired Adolf Hitler and modeled his Silver Shirts after Nazi storm troopers. His troops were “the cream, the head and the flower of our Protestant Christian manhood,” Pelley proudly claimed. The men were also isolationist, pro-fascist and virulently anti-Semitic.

Membership in the organization grew rapidly, with perhaps fifteen thousand national members at its peak. Applicants were required to furnish a photograph and personal information, including “racial extraction,” religion, physical disabilities, military training and personal finances. Uniforms featured “dark blue corduroys trousers, tie, leggins [sic], and a silver shirt with a scarlet ‘L’ (for loyalty) on the shoulder.”

In San Diego County, Alpine resident Willard W. Kemp led the Silver Shirt Pacific Coast Division. A San Diego post headed by Charles T. Lee met at the Hotel San Diego and in an East San Diego bookstore on University Avenue.

In April 1934, “Captain” Lee was invited to address a group of veterans called the Hammer Club for its weekly luncheon at the U.S. Grant Hotel. Members were promised “an explanation of the ideals and aims of the Silver Shirt Legion.”

Controversy greeted the Hammer Club the very next week when the invited speaker was Rabbi H. Cerf Strauss of Temple Beth Israel. Denouncing the Silver Shirts as “anti-American, anti-Jewish, and anti-Catholic,” Rabbi Cerf accused Pelley’s organization of fomenting revolutionary activities against the American government.

In his Silver Shirt uniform, William Pelley stands before his followers. From Pelley’s autobiography, The Door to Revelation (1939).

It was a severe charge but was taken seriously by Congressman Charles Kramer’s investigators. On August 5, 1934, the Kramer committee stunned the public by announcing that “armed men known as Silver Shirts, with secret auxiliary called Storm Troopers and avowedly organized to change the Government of the United States” were drilling in the San Diego area.

“Poppycock,” declared San Diego police chief John Peterson. “There have been no drills in the city [and] the back country is calm.” County Sheriff Ed Cooper seconded Peterson, adding that his men kept a close watch on the organization, which they knew met occasionally at the Willard Kemp ranch east of El Cajon. The members never drilled, the lawmen claimed, but a few members did engage in some “inconsequential” target practice.

The charges appeared more credible when the committee released testimony from two “infiltrators.” A former U.S. marine, Virgil Hayes, related a chance meeting near Oceanside in April. Sitting alongside Willard Kemp on a train to San Diego, Hayes mentioned to Kemp that he was in the U.S. Marine Corps. “Kemp told me he was the West Coast commander of the Silver Shirts. He asked me if I had access to government guns and ammunition, and when I told him I had, he made the offer.”

William Dudley Pelley. From the Saturday Evening Post, May 27, 1939.

The offer was ten dollars for rifles, fifty dollars for machine guns and twenty dollars per case for ammunition. Kemp added that any actions by the Silver Shirts would be countenanced by the San Diego sheriff’s office, with the exception of the Undersheriff Oliver Sexson. The Silver Shirts would be protected, Kemp assured, but “the under-sheriff is a Jew and would be liquidated.”

Hayes told Kemp that he would get the arms. Instead, he reported the encounter to his superiors, who ordered him to join the Silver Shirts. “I was made an instructor,” he told the congressional committee. “I taught them the use of small arms and street fighting.” Hayes’s pupils were well armed with rifles, pistols and shotguns, but “mainly Springfield rifles bearing a United States Government mark.”

A second marine appearing before Kramer’s committee told a more chilling story. Corporal Edward Gray testified that the previous spring, the Silver Shirts had planned to “capture” San Diego City Hall:

It was planned for early May, when the Communists were to stage a May Day celebration…200 armed, trained Silver Shirts had orders to converge on the city from the outskirts. They counted on the Communists going in before them and taking the city by storm. Then, in the confusion, the Silver Shirts were to overthrow the Communists, their avowed enemies.

The Silver Shirts’ putsch failed when the expected Communist demonstration never appeared. A few weeks later, the Silver Shirts discovered that Corporal Gray was a spy. “Storm troops” caught the marine near C Street and Broadway and beat him, sending him to the hospital with a fractured skull.

With the public exposure of their aims and intentions, tolerance for the Silver Shirts faded quickly. The Hotel San Diego refused to allow meetings; other meeting places were closed to the group.

The national leader of the Silver Shirts lasted a while longer. In 1936, William Pelley ran for president, promising to incorporate his soldiers into the federal armed forces and do away with the Justice Department. “I’m calling in every Gentile in these prostrate United States to form with me an overwhelming juggernaut…for Christian government.” Only the state of Washington permitted Pelley on the ballot; he received 1,598 votes out of nearly 700,000 ballots cast.

In July 1942, Pelley was convicted in federal court on charges of insurrection and sedition. Sentenced to fifteen years, he served ten. He died in obscurity in 1965.

A TEXTBOOK CONTROVERSY

The effort of the American Legion to eliminate all un-American teachings from the schools of the nation has been a real success…In fact, radical advocates of the use of the Rugg books have frankly and publicly admitted that the books are being “quietly removed from schools.”

–R. Worth Shumaker, American Legion convention, September 19, 1942

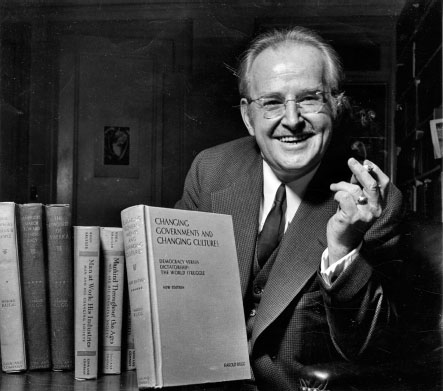

In the 1930s, the social science textbooks authored by Dr. Harold Rugg were standard classroom fare in schools throughout the United States. The books sold 1.3 million copies in ten years and were studied in more than five thousand school districts, including in San Diego. But late in the decade, the books came under remarkable public scrutiny and were attacked as “subversive” and “un-American.”

Harold Ordway Rugg was a professor of education at Teachers College, Columbia University. The descendant of a Revolutionary War minuteman, Rugg was a respected historian, teacher and educational theorist. In 1922, he directed the creation of a social science booklet series for middle school students (grades six to eight). Six years later, he coauthored a groundbreaking book on progressive education called The Child-Centered School: An Appraisal of the New Education.

Dr. Harold O. Rugg was a successful textbook author but a lightning rod for right-wing critics. Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College.

In 1929, the schoolbook publishers Ginn and Company began turning the work of America’s best-known educator into textbooks. For secondary schools, there was a six-volume “Rugg Social Science” series; for elementary schools, there was the fourteen-volume “Man and His Changing Society” series. The books sold widely and established a model for textbook publishing that still exists.

But despite their popularity, Rugg’s textbooks began to draw controversy. In 1935, a citizens’ group in Washington, D.C., complained about volume 1 of the high school series, An Introduction to American Civilization. Calling the book “communistic,” the group demanded the book’s withdrawal. A school board committee investigated but rejected the demand when the members found “no mention of communism in this textbook, not even a suggestion of it.”

The corporate world also complained about Dr. Rugg. When the American Federation of Advertising discovered a textbook phrase that said that “advertising costs were passed on to consumers,” it accused Rugg of criticizing American selling practices by his suggestion that marketing raised the prices of consumer goods.

A national attack on the Rugg textbooks began in 1939 when magazine publisher and Hearst newspaper columnist Bertie C. Forbes charged that Rugg’s textbooks were “viciously un-American.” Rugg, who had once visited the Soviet Union, was also accused of being “in love with the way things are done in Russia.”

In Englewood, New Jersey, where Forbes was a member of the school board, a “schoolbook trial” began, and Dr. Rugg was called on to defend his textbooks. To his relief, he found parents and teachers overwhelmingly supportive. The school board rejected Forbes’s demand that the books be banned. But attacks on Dr. Rugg continued to escalate. In San Diego County, local patriotic groups and businessmen denounced the textbooks. The Daughters of the American Revolution condemned the books as subversive, and the chamber of commerce complained that they were an “indication of Communism boring from within.” San Diego’s superintendent of schools, Dr. Will C. Crawford, announced that a curriculum committee would study the matter.

Among local educators like Crawford, criticism of the Rugg series presented a conundrum. The textbooks had been used in San Diego for ten years and were, according to Crawford, the most nearly “complete textbooks dealing with social science available on the American market.” Walter Hepner, president of San Diego State College, agreed that the books were valued for their “completeness” but allowed that he “never liked them.” J.M. McDonald, superintendent of the Sweetwater school district, promised that “if any subversive matter is contained in these books they will be removed from our system.”

The San Diego County Grand Jury decided to investigate the matter in 1940. In its annual report, released in mid-January 1941, the jury hit the books hard. “It was found,” the report read, “that the [Rugg] books had a tendency to tear down the democratic form of government. The committee therefore recommends that the book be not used in public schools.” The report added that educators “admitted that parts of the books were definitely subversive.”

At least one educator took issue with the “admission.” Dr. John S. Carroll, the deputy superintendent of county schools, declared that “no critic ever has brought to me a marked paragraph of the book and definitely called it subversive.” But Carroll added a disclaimer: “The author may be said, at times, to express the ultra-liberal viewpoint.”

In San Diego school districts, officials were quick to distance themselves from the controversy. Some responded to the grand jury report by announcing that the Rugg social science series was already being discontinued. Dr. Crawford claimed that the replacement task had been taken prior to any public comment, “not because they were subversive, but because they were too advanced for junior high school students.”

Other educators loudly denied that they had ever used Rugg textbooks. Martin Perry, principal of Escondido High School for twenty-three years, said that the books “have never been used in this school since I have been here.” The principal of Coronado High School declared that the books had never been used at his school “and they are not even in our library.”

As sales of Rugg’s textbooks declined in the early 1940s, organizations such as the American Legion congratulated themselves for their perceived role in banishing the books. The Rugg series was replaced in large measure by books authored by Stanford University professors Paul R. Hanna and Isaac James Quillen—men who were perhaps as “progressive” as Rugg yet managed to avoid the politicized attacks from the “Rugg-beaters.”

THE LAST TEMPTATION OF THE BOOK CENSORS

This is a book of defamation, of depravity, written by an atheistic, degenerate mind—and yet it is honored with a place in Public Libraries.

–Jack Childres, San Diego Patriotic Society, January 1963

Public libraries often confront efforts to censor their collections. In 1963, San Diego was among scores of libraries caught up in a bitter, nationwide campaign to remove the controversial novel The Last Temptation of Christ from library shelves.

The critically lauded book by Greek novelist Nikos Kazantzakis was published in 1951, but an English translation would not appear in America until 1960, three years after the author’s death. Overshadowed, perhaps, by Kazantzakis’s better known Zorba the Greek, Last Temptation received little attention in America until 1962, when patriotic and religious groups began calling the book “blasphemous” for its fictional portrayal of Jesus Christ.

In San Diego, an insurance agent named Jack Childres led a drive to ban the book from local libraries. Childres was chairman of the recently formed San Diego Patriotic Society, which claimed a membership of more than one thousand San Diegans. “The purpose of our society is to print the truth,” Childres explained. “We believe this book is part of a Communist conspiracy to destroy the morals of our youth and undermine Christianity.”

Of concern to Childres and other detractors of the novel were passages that they believed depicted Jesus as mortal and subject to temptations and desires of a “common man.” They insisted that the book be removed from taxpayer-supported libraries.

City Librarian Clara Breed countered that her staff selected books based on their positive values and that library collections should reflect all sides of controversial issues. The author Kazantzakis, she pointed out, had an outstanding international reputation, and his book had been well reviewed. “We take no sides on matters concerning politics or religion,” said Miss Breed, adding that “there is no record of any book ever being withdrawn from this library under pressure from any group.”

In January 1963, the Patriotic Society mimeographed ten thousand leaflets, which detailed their concerns and “urged San Diegans to work to stamp out this book.” Copies were sent to citizens, churches, librarians and city and county officials.

The leaflet stirred a flurry of letter writing from a troubled public. A retired attorney, Ralph Allen, demanded the removal of the book from libraries and urged that Clara Breed be fired or at least “dealt with severely.” “The purpose of the Public Library is to elevate people. If a few communists and a few atheists want that book, let them buy it, but let’s not make it available with tax money.”

A Methodist minister also expressed alarm that the book was available in libraries. Writing to the County Board of Supervisors, Reverend Orval Butcher of the Skyline Wesleyan Church in Lemon Grove asked that “responsible authorities remove the book from public circulation on the basis that it defames the holy character of the divine son of God.”

The Catholic Diocese of San Diego reacted more pragmatically. Officially, the novel was included in the church’s “List of Prohibited Books” for its “salacious” characterization of the life of Christ. But the diocese declined to join the public protest, noting that “as soon as a book is publically condemned thousands want to buy it.”

Laurence Klauber, library commissioner, and Clara Breed, city librarian, turned back efforts to ban a popular book title. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

As letters and phone calls flooded San Diego’s city council, City Manager Tom Fletcher asked the three-member Library Commission to consider the matter. On February 15, the commission held a public hearing in the auditorium of the Central Library on E Street. Clara Breed recalled:

Everyone was given an opportunity to speak. The censors were all there and included not only members of the John Birch Society but good citizens who thought they were defending morality, the church and the American way of life. Not one had read the book.

Local printer John Kellis spoke up to say that Kazantzakis had been excommunicated by the Greek Orthodox Church for his pro-Communist writings. Not knowing that Kazantzakis had died in 1957, Kellis added, “I don’t have any information that he is but I suspect the author is a member of the Communist party.”

Other speakers at the hearing believed that the book had nothing to do with religious heresy or Communism. “It exalts Christ,” said Sylvia Warren, the wife of a local college professor. “It shows great spiritual people have the normal temptations of human beings, and that Christ was able to conquer them.”

Alvin J. Abrams, of the San Diego chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), urged the commission to uphold “American guarantees of freedom of speech, press, and especially freedom of religion” and to not be party to “an obnoxious form of censorship.”

After listening to all the statements, library commissioner Beatrice Brenneman made a motion “that the Library Commission reaffirms our existing book selection policy and that we stand firmly beside our wise Librarian in opposition to censorship and recommend retention of the book under discussion on the library shelves.” Seconding the motion was Commissioner Thomas O. Scripps, who added, “Give light and the people will find their own way.”

City Manager Tom Fletcher supported the commission’s decision, and the controversy soon died. Ironically, as the result of the attempt to ban the novel, library circulation of The Last Temptation of Christ soared. “If you really want to suppress a book,” observed Laurence Klauber, president of the Library Commission, “don’t mention it at all. If you want to increase its popularity, ask that it be removed from library shelves.”