PART VIII

SAN DIEGANS TO REMEMBER

DOUGLAS GUNN

No man was ever more thoroughly identified with the history of a city than is Douglas Gunn with that of San Diego. No city has ever had a more sincere and zealous advocate.

–San Diego Union, January 12, 1888

Among San Diego’s unsung pioneers, Douglas Gunn is a man worth remembering. The onetime publisher of the San Diego Union was the city’s first “modern” mayor and a tireless promoter of his adopted city.

Born in Ohio in 1841, Gunn was twelve when his family moved to California, where his father, Dr. Lewis C. Gunn, purchased the Sonora Herald. Here Gunn learned the printing trade. When the family moved to San Francisco in 1860, young Gunn worked with his father on the San Francisco Times, edited by Dr. Gunn. By the time the family moved to San Diego in 1868, young Gunn was an experienced newspaperman.

He purchased a small interest in the recently established San Diego Union and walked several miles daily from his home in Alonzo Horton’s “New Town” to the Union office in Old Town. Gunn started as a reporter and printer but assumed editorial control of the weekly newspaper in 1871. He moved the press to New Town and on March 20, 1871, he printed the inaugural issue of the Daily Union, the first daily newspaper in San Diego.

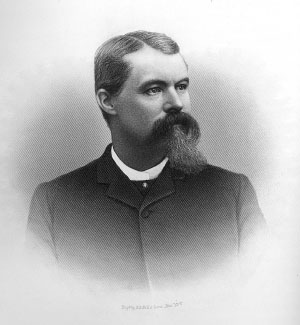

Mayor Douglas Gunn was a tireless promoter of San Diego. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

Gunn bought out Union co-owner Edward Bushyhead in 1873 for $5,000 in cash. He quickly expanded the newspaper’s size as readership thrived during a brief real estate boom, driven by belief that a railroad would soon extend to San Diego. But the railroad project collapsed amid the Panic of 1873, which plunged the nation into a severe depression that lasted for the remainder of the decade.

As the Union struggled to survive, Gunn did most of the local reporting and news editing by himself. The daily slowly grew and prospered in the 1880s. He sold the newspaper in August 1886 to the San Diego Union Company, managed by Colonel John R. Berry.

With his publishing responsibilities gone, Gunn devoted his time to investing in the growing city. As the editor of the Union, Gunn had lobbied hard for a railroad connection to San Diego. When the railroad finally arrived in 1885, the huge real estate “boom of the eighties” took off in San Diego.

Gunn bought heavily, buying several properties in downtown and the Middletown area. He built a particularly handsome building at Sixth and F Streets, called the Express Block. In a lengthy article he wrote for the Los Angeles Times on January 1, 1887, the retired editor boasted of San Diego’s new prosperity, “built first upon the anticipation and finally the realization of railroad connection with her harbor.”

Gunn’s article noted that the city population had jumped from 7,500 at the start of 1886 to more than 12,000 by year’s end and that new arrivals exceeded departures by 1,300 per month. The county population had more than doubled to over 35,000. But cheap land was still available, according to Gunn, and he prophesied, “The ‘boom,’ as it is called, will not stop while an acre remains unoccupied.”

In early 1887, Gunn decided to promote San Diego to the world in a lavish book that would not only describe the region in text but also include expensive photographs to illustrate the features of the city and county. He hired a Los Angeles photographer, Herve Friend, of the American Photogravure Company. The two men traveled about the county, covering an estimated 1,200 miles while Friend photographed the wonders of San Diego County.

The Union described the work of its former publisher: “The illustrations will comprise natural scenery as well as prominent improvements. The process employed is almost equal to steel engraving, and the work when completed will far surpass anything ever attempted before.”

Gunn’s Picturesque San Diego appeared in October 1887. Printed in Chicago, the hardcover, ninety-seven-page book contained seventy-two photogravure plates. One thousand copies were offered for sale at ten dollars each. Reviewers from San Francisco to New York City applauded the book. A paperback version called San Diego Illustrated, which contained woodcut images and sold for one dollar, was released five months later. Two thousand copies of the second book were donated by Gunn to the chamber of commerce for mail distribution to the East Coast.

On the heels of this success, Gunn decided to run for city mayor. Nominally a Republican, Gunn ran for mayor on the “Citizens Non-Partisan” ticket against the “Straight Republican” candidate, John R. Berry—the same man who had followed Gunn as editor of the Union. After a hard-fought campaign, Gunn won the election on April 2, 1889, by 428 votes. He would serve only one two-year term. His tenure was the first under a historic city charter that established the office of mayor, as well as a two-house city council and professional police and fire departments.

By the fall of 1891, Gunn was struggling financially. Once worth an estimated $100,000 during the great boom, he had lost heavily when the bubble burst in late spring 1888. After his term as mayor, Gunn hoped to recoup his fortunes. Instead, the “financially embarrassed” civic leader borrowed heavily at ruinous interest rates.

The ruins of the Mission San Diego de Alcala in 1887, as photographed by Herve Friend for Douglas Gunn’s Picturesque San Diego.

On November 29, 1891, the Union announced news that “stopped the pulse of the entire city.” Fifty-year-old Douglas Gunn had been found dead in his office at 735 Sixth Street. Gunn, who had never married, was survived by his elderly parents; his brother, Chester Gunn, a county supervisor; and his sister, Anna Lee Gunn, who was married to businessman George W. Marston. He was interred at Mount Hope Cemetery, accompanied by “the largest attendance ever witnessed at a funeral in San Diego.”

ALBERT G. SPALDING

A.G. Spalding, the well known athletic goods man, has decided to make San Diego his home, as is evidenced by the arrival of a carload of elegant furniture and a double-seated locomobile for him. Last year Mr. Spalding married a lady at the Point Loma Homestead.

–San Diego Union, February 23, 1901

“Spalding” is perhaps the world’s most recognized name in sporting goods. Less well-known is the man who founded the famous company: Albert Goodwill Spalding, a member of the baseball Hall of Fame, business magnate and prominent San Diegan.

Growing up in Rockford, Illinois, A.G. Spalding began playing the new sport of baseball as a teenager in the 1860s—learning the game, it is alleged, from a Civil War soldier. As a pitcher for the Boston Red Stockings in the formative years of major-league baseball, Spalding became a national sports hero. He was the first pitcher to win two hundred games and led his Boston team to four consecutive pennants. Spalding retired in 1876 at age twenty-seven, concerned—as he later told his son, Keith—that advancing age was slowing his reflexes.

Spalding’s second career began when he borrowed $800 from his mother and opened a sporting goods store with his younger brother in Chicago. Selling baseballs was a hit for the A.G. Spalding and Brothers Company. The retired sports hero paid the National League to use his baseballs, which he advertised as the “official ball” of the national pastime. Prosperity soon followed as the company manufactured and sold bats and gloves, tennis rackets, basketballs, golf clubs—anything related to sport, including a lucrative annual called Spalding’s Official Baseball Guide.

Spalding would be closely associated with baseball the rest of his life. From 1882 to 1891, he owned the Chicago White Stockings (today’s Cubs) and won five pennants. Despite his experience as a ballplayer, as an owner Spalding fought early player efforts to unionize and strongly supported the “reserve clause,” which bound players to one team.

Hall of Fame baseball player and prominent San Diegan Albert G. Spalding. Bain Collection, Library of Congress.

One of Spalding’s most interesting legacies was a history commission he sponsored that researched the origins of baseball. Despite obvious links to the British games of rounders and cricket, Spalding’s commission promoted the myth that baseball was invented by an American, Abner Doubleday, who it was said created the game at Cooperstown, New York, in 1839.

Spalding spent the last chapter of his life in San Diego. In July 1899, his wife, Josie, died. Within a year, he had married Elizabeth Mayer Churchill, a childhood friend from Illinois and his mistress of several years. Elizabeth was a disciple of Katherine Tingley, who ran the Point Loma community of the Theosophical Society, an institution that promoted the study of religious philosophy along with a regimen of self-improvement that included the performing arts. Elizabeth became the musical director for “Lomaland” and a member of Madame Tingley’s inner circle.

While Spalding did not share his wife’s enthusiasm for theosophy, San Diego did offer new business challenges and opportunities for civic involvement. The couple built a grand Victorian house on the grounds of the Theosophical Society (which still stands today on the campus of Point Loma Nazarene University), and Spalding turned his attention to San Diego.

In 1907, Spalding joined other San Diego business elites—newspaper publishers John D. Spreckels and E.W. Scripps and department store owner George W. Marston—to protect the site of Presidio Hill above Old Town, where Father Junípero Serra had founded San Diego in 1769. The men purchased the spot, where Marston would later build the Serra Museum and establish the San Diego Historical Society.

Spalding was also interested in “good roads.” When San Diegans approved a bond issue in 1907 to improve local roads, Spalding was appointed to a County Highway Commission along with Spreckels and Scripps. Unfortunately, “the three millionaires” bickered among one another, and Spalding resigned.

Road development in Spalding’s own neighborhood went better. He was instrumental in building roads connecting Point Loma with Ocean Beach, Roseville and San Diego, and he convinced the federal government to extend Catalina Drive (major portions of which Spalding owned) to the tip of Point Loma, now the site of Cabrillo National Monument.

One of Spalding’s last acts was the creation of Spalding Park on beachfront property he owned. Hiring workmen under the direction of a Japanese landscape architect, he spent $2 million on the area he would name Sunset Cliffs. Local historian Ruth Varney wrote in her book Beach Town:

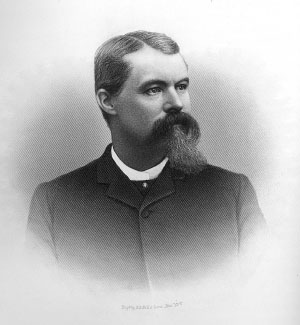

Decorative palm-thatched roofs sheltered benches where the view was spectacular. Japanese style arched-rustic bridges spanned narrow, deep clefts where the waves surged in and out endlessly…At the foot of Adair Street a path led down to two sets of cobblestone steps ending on a flat projection of rock where “Spalding’s Pool” was carved into sandstone. It was about 15 by 50 feet, three feet deep at the near end, sloping to six feet where the waves at high tide broke over it and washed it clean.

Spalding spent $2 million on the landscape architecture of the beach area he called Sunset Cliffs. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

Spalding even added a dressing room at the top of the cliff for users of the “pool.” In later years, ocean tides would erode and eventually reclaim all of Spalding Park.

In August 1915, the sixty-five-year-old Spalding suffered a minor stroke. He appeared to be recovering, but on September 9, he died suddenly. An elaborate funeral service was held two days later at his home before cremation at Greenwood Cemetery.

Spalding’s estate, valued at $1.2 million, was left almost entirely to his wife, Elizabeth. His son, Keith, from his marriage to Josie, challenged the will, arguing that “for several years before his death his father was not in his right mind.” No less interested was Madame Tingley, who had always expected to be well treated in the will. After two years of litigation, an out-of-court settlement awarded $500,000 to Keith and $700,000 to Mrs. Spalding. Tingley and the Theosophical Society received nothing, not even after the death of Elizabeth Spalding in 1926.

LEON DE ARYAN

Shivering like a nudist in a rumble seat and leaving a trail of bayfront water behind him, C. Leon De Aryan, editor of The Broom, appeared at the police station today charging that five longshoremen had thrown him into the bay off the Municipal pier.

–San Diego Sun, November 24, 1936

Public hostility rarely bothered C. Leon de Aryan. The owner and publisher of the San Diego newspaper called The Broom craved attention of any kind and often received it from his provocative editorials denouncing organized labor, international bankers, Communists, Jews and President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

San Diego’s notorious dissenter was born in Romania in 1886. The son of a Greek father and a Polish mother, he was christened Constantine Leon Legenopol. After the death of his father, young Legenopol and his mother moved to Austria. At age nineteen, his mother placed him in an insane asylum, but he was released after doctors in Vienna diagnosed his condition as “family persecution.”

Legenopol trained as a civil engineer and worked on engineering projects for the British in Egypt and India before immigrating to America in 1912. He soon joined the U.S. Army, but soldiering proved a poor career move, and after a dishonorable discharge, he fled to Mexico. He returned to the United States when World War I ended. Living in Los Angeles in 1926, he became a naturalized citizen and changed his surname to “De Aryan” to reflect his ambition to champion the philosophy of the “Aryan race.”

De Aryan arrived in San Diego four years later and worked for a short time for the City of San Diego in the Public Works Department. His newspaper premiered on October 6, 1930. For the next thirty-five years, The Broom appeared on Monday in San Diego—its pages filled with news and editorials expounding the virtues of personal free will, vegetarianism and faith in Jesus Christ. De Aryan’s columns also vented anger against labor unions, taxation and government interference in daily lives.

In 1935, De Aryan ran for mayor. As the “anti-vice candidate,” he pledged to free the city from “domination by the gamblers and the brothels” and to make sure “the underworld riff-raff of the nation” would not flood San Diego during the California Pacific Exposition. Voters were unimpressed. In a race won by Percy J. Benbough, De Aryan garnered less than 1 percent of the votes cast.

The next year, the publisher’s anti-union writings got him into trouble with the local longshoreman’s union. Confronted at the foot of Broadway by several dockworkers, De Aryan was asked if he was the one writing articles against strikers. When he answered yes, the men pummeled De Aryan and then tossed him into the bay. Dripping wet, De Aryan marched to the local police station and filed charges.

The notorious publisher and “crackpot” C. Leon de Aryan, photographed at the county courthouse. San Diego History Center.

But De Aryan’s diatribes against organized labor paled in comparison to his published views on Jews. Always denying that he was anti-Semitic, De Aryan claimed that his critics were “ignorant and narrow-minded people.” “I stand with the Truth” became his mantra.

De Aryan’s “truth” revealed that Jews were “conspirators” who were driving the world to war in order to “plunder their dupes.” He decried the “bloody exploitation carried on by International Jewish Bankers.”

In September 1940, after most of Europe had fallen to Nazi Germany, De Aryan wrote, “the Jews are scuttling like cockroaches out of Europe. Their international bankers and wholesale murderers and betrayers of France are safely esconded in New York and Canada; thousands of other Jewish refugees are taking jobs from American employees.” De Aryan added, “Still I do not hate them because it is against my religion.”

His confrontational views drew the attention of the California Senate’s Un-American Activities Committee in April 1942. Testifying in Los Angeles, De Aryan proudly told the committee he had pursued an active anti-Communist policy in The Broom from “practically the first issue.” Because of this, he claimed, the Communists were after him and even threatened him on the telephone. Fortunately, he could identify the Reds on the telephone, explaining to the committee that all Communists have a “guttural sound” in their voices. Examining De Aryan’s testimony, a government attorney concluded that the publisher was a paranoid “crackpot” who would probably savor prosecution for the sake of publicity.

That summer, as De Aryan prepared to run as a Republican candidate for Congress, a federal indictment for sedition was served by a telegraphic warrant from Los Angeles. De Aryan was booked into San Diego County Jail. Blaming his arrest on the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and Communists, De Aryan began a short-lived hunger strike but continued to publish his newspaper with the aid of friends and a sympathetic printer.

He was released after several weeks, but a new indictment brought De Aryan and twenty-seven other suspected Nazi sympathizers to Washington, D.C., where they went on trial in April 1944; all were charged by Attorney General Francis Biddle with conspiracy to break down the morale of the U.S. military.

De Aryan’s fellow defendants in the “Great Sedition Trial” included several well-known American fascists such as William Dudley Pelley, Lawrence Dennis and Robert Noble. The dissidents all opposed the war and shared a loathing of organized labor, Jews, communism and President Roosevelt. A reporter noted, “Seldom have so many wild-eyed, jumpy lunatic fringe characters been assembled in one spot, within speaking, winking, and whispering distance of one another.”

The indictments of the American “fascists” were popular with the public, but with no evidence to support charges that they had aided the enemy, the trial was a fiasco for the government. The defendants were unruly in court and alternately “moaned, groaned, laughed aloud, cheered and clamored.” On one occasion, they wore Halloween masks. The case was never submitted to the jury and was finally dismissed in December 1945, seven months after the war ended in Europe.

De Aryan returned to San Diego and continued publication of The Broom. He drew public attention again in 1952 with a lawsuit to block fluoridation of the water system in San Diego. His suit failed, but voters would ultimately reject the water treatment plan. With lessening fanfare, De Aryan continued weekly publication of his newspaper until his death on December 13, 1965, at age seventy-nine.

The masthead of De Aryan’s newspaper, The Broom. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

SCOTT O’DELL

Island of the Blue Dolphins began in anger, anger at the hunters who invade the mountains where I live and who slaughter everything that creeps or walks or flies.

–Scott O’Dell, in Psychology Today, January 1968

Writer Scott O’Dell was angry. Anxious over hunters killing wildlife near his Julian home, he needed to do something about it. He considered writing a letter to the newspapers but decided that such a letter would be unseen or easily dismissed. “So I wrote Island of the Blue Dolphins about a girl who kills animals and then learns reverence for all life.”

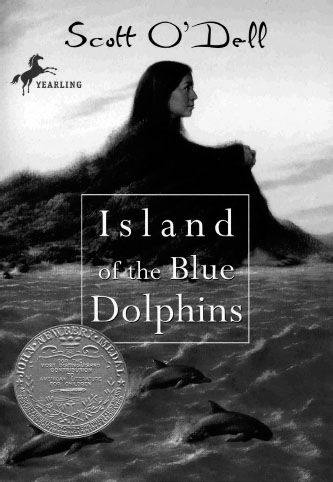

O’Dell’s novel of a young Indian girl abandoned on harsh San Nicholas Island in the early 1800s is also a story of courage and self-reliance. Published in 1960, Island of the Blue Dolphins became one of the top twenty young adult books of all time, with more than 6 million copies sold and translations in twenty-eight languages.

Its famed author was born Odell Gabriel Scott in Los Angeles in 1898. The family moved frequently, living in San Pedro, Rattlesnake Island (Terminal Island) and eventually Long Beach, where O’Dell graduated from high school. Several colleges followed, but O’Dell never earned a degree.

The critically acclaimed novel Island of the Blue Dolphins was Scott O’Dell’s best-known work. Bob and Tennie Bee Hall.

An avid reader as a boy, O’Dell considered becoming a writer after his parents told him that he was related to the British author Sir Walter Scott (his great-grandmother’s first cousin). He took up writing professionally in his early twenties by penning articles for local newspapers, where a typesetter accidentally transposed his first and last name. Scott approved of the new name and soon had it legally changed.

In the 1920s, O’Dell found writing work in the silent film industry. He critiqued movie scripts for Palmer Photoplay Company and taught a mail-order screenwriting course. At age twenty-five, he wrote his first book, Representative Photoplays Analyzed.

Working for Paramount Pictures as a set dresser, O’Dell had a brief role in the The Son of the Sheik, where his slender hand appeared as a stand-in for Rudolf Valentino’s stubby fingers. He later worked for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as a cameraman and shot scenes of Ramon Novarro in Ben-Hur.

His first novel, Woman of Spain: A Story of Old California, appeared ten years later. Greta Garbo convinced MGM to buy the screen rights to the book. The book was never filmed, but sale of the rights supported O’Dell through the Great Depression.

After a brief stint in the U.S. Army Air Force during World War II, O’Dell joined the Coast Guard Auxiliary. He finished the war doing night patrol duty off the Southern California coast, sometimes alongside fellow volunteer Humphrey Bogart.

O’Dell was fascinated by California history and used the Mexican-American War as inspiration for his second novel, Hill of the Hawk. A review in Westways magazine called O’Dell’s work “an usually fine historical novel” and praised his lively description of the Battle of San Pasqual.

After a stint as book review editor for the Los Angeles Daily News, O’Dell began writing historical works full time. Country of the Sun: Southern California, an Informal Guide appeared in 1957. Tracing the history of the region, O’Dell wrote a particularly descriptive account of the 1870s gold rush in Julian, a community where he was then living.

The O’Dell home in Julian was a remodeled packinghouse, with three-foot-thick stone walls, set in an apple orchard called Stoneapple Farm. With his wife, Dorsa, O’Dell grew apples and explored story ideas, usually based on incidents in California history.

From his research for Country of the Sun, O’Dell had discovered the true story of the “Lost Woman of San Nicholas,” a Native American who had lived alone for eighteen years on California’s most isolated Channel Island. She had been abandoned on the island in 1835 when the indigenous Nicoleño Indians moved to the mainland. Reportedly, she had jumped from the ship that carried her people to the coast. She was found in 1853 and brought to the Santa Barbara Mission, where she died a short time later.

Scott O’Dell’s fictional reconstruction of the life of the abandoned “Karana” on the Island of the Blue Dolphins was an instant classic. The well-reviewed novel sold widely and was frequently adopted for classroom use in schools. In 1961, it won the prestigious John Newbery Medal for the most distinguished contribution to literature for children.

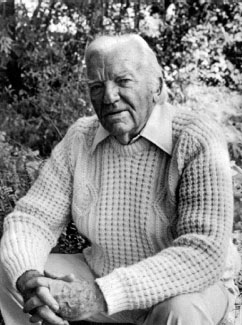

The celebrated author Scott O’Dell. Bob and Tennie Bee Hall.

The book’s success made the Julian writer a celebrity. O’Dell traveled throughout California, speaking to school assemblies and classes. In early 1963, O’Dell estimated that had spoken to forty thousand children in two years. A film version of the story appeared in 1964, starring George Kennedy and Celia Kaye as Karana.

O’Dell, who would stick to writing for young adults for the rest of his career, had discovered the rewards of writing for the young. In 1968, he commented that with the publication of adult books, the author could expect to hear “most from his friends and none from his enemies.” Afterward, “there is silence.” “But with children, if they like your book, the reverse is true. They respond in numbers, by the thousands of letters, over an indefinite period of time.”

After the Island of Blue Dolphins, O’Dell wrote nearly thirty more popular and critically esteemed novels for young readers. He spent his last years in Westchester County, New York, before his death at age ninety-one in 1989. His ashes were scattered in the ocean off La Jolla.

DONAL HORD

One of America’s greatest artists left an impressive legacy in San Diego. Donal Hord, best known for his monumental stone figures, created works of sculpture that have endured at sites throughout our region.

The artist was born as Donald Horr in Prentice, Wisconsin, in 1902. His parents divorced when he was only seven; the unhappy mother supposedly renamed her son to spite the father by moving the last d from his first name and adding to his last name.

Donal Hord carving hard diorite stone with an air hammer to create Spring Stirring. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

Donal and his mother moved to Seattle in 1914. Here Donal began to display an interest in art by taking lessons in watercolors and carving his first small pieces of sculpture. The young artist was sickly as a child, and a bout with rheumatic fever at age twelve left him with a weakened heart. After a doctor recommended a warmer climate, mother and son boarded a steamship for San Diego.

Attending high school was difficult for Donal because of his poor health. However, he was a regular visitor to the San Diego Public Library, where “he was always underfoot,” recalled a librarian. A voracious reader, Hord checked out books by the armload. Years later, he would show his gratitude to the library by donating his large personal collection of books and many works of art.

At age fifteen, Hord began taking art classes from Anna Valentien at the San Diego Evening High School. Valentien was a notable figure in San Diego’s blossoming arts and crafts movement. She had also studied sculpture with Auguste Rodin in Paris. From Valentien, Hord began learning the rudiments of modeling and sculpture.

Hord continued his education in the 1920s, aided by grants and scholarships. He learned bronze casting at the Santa Barbara School of Arts and spent eleven months in Mexico studying ancient and modern forms of Native American art that would strongly influence his own personal artistic style.

Most of his early work was in bronzes, which required clay modeling and then casting. The process was frustrating at times; a bad cast could ruin weeks or months of work. Hord came to prefer direct mediums such as hardwood or stone. He was particularly fascinated by materials used by ancient sculptors, who had carved their work directly on the materials. Diorite, for example, was a favorite hard stone used in Middle Eastern civilizations such as Egypt, Babylonia and Assyria. A famed work in diorite extant today is the Code of Hammurabi, inscribed on a seven-foot pillar in about 1790 BCE.

Hord once explained to a newspaper reporter that he chose hard mediums because “they were such beautiful materials.” Sculpting in hardwoods such rosewood or lignum vitae or rocklike diorite or jade was difficult. “In fact, I would much rather have used something easier to cut,” he admitted. But hard surfaces could be worked with precision and took a finish that was beautiful to touch as well as sight.

In 1934, Hord was accepted to the Depression-era Federal Art Project and given a salary of seventy-five dollars per month. The opportunity to carve in stone followed. For La Tehuana, a patio fountain in the courtyard of the House of Hospitality in Balboa Park, Hord used Indiana limestone to create the figure of a Native American woman pouring water from an olla.

It took Hord and his assistant, Homer Dana, ten weeks to complete La Tehauna. Hord thought that he could do his next project in twenty weeks. But Aztec took fourteen months. It was his first experience with diorite, an extremely hard stone. “I learned, by blister, bruise and dark despair,” Hord said, “that diorite is a wonderful medium to instill discipline.”

Aztec, which became the iconic “Montezuma” on the campus of San Diego State College, was carved from a two-and-a-half-ton block of black diorite quarried near Escondido. After months of hard work with hand tools, a quarryman suggested the work would go a lot faster with an air hammer. Homer Dana remembered, “We picked a service station air compressor, and used it for years and years.”

Hord’s next major project would be Guardian of the Waters. Working from a thirty-ton block of gray diorite quarried near Lakeside, Hord supervised a team that began by trimming off huge one-hundred-pound slabs. “I stayed off of it,” Hord recalled, “until we got to the air hammer and then I started in to work.”

The monumental Guardian of the Waters stands in front of the San Diego County Administration Building. Special Collections, San Diego Public Library.

The thirteen-foot-tall statue of a woman holding an olla of water on her shoulder was mounted on a ten-foot base decorated with a mosaic of 200,000 pieces. After two years of work, it was moved into place on the harbor side of the Civic Center—today’s County Administration Building—and dedicated on June 10, 1939.

Another recognizable Hord sculpture, passed by thousands of people daily, is a set of bas-reliefs flanking the entry doors to the Central Library at 820 E Street. Integrating sculpture with architecture, the two “literature” panels—ten feet high and six feet wide—represent the heritage of reading brought from the cultures of east and west.

The bas-reliefs were a return for Hord to the molds and castings of his early career. In his backyard studio in Pacific Beach, the panels were first sketched and made as small clay models. Larger, full-scale clay models came next, created in a wooden frame. Plaster molds were then made from the clay, which held the casting concrete for the final work. Cranes lifted the panels into place on the library’s exterior on September 3, 1953, several months before the new building opened to the public.

That same year, Hord arranged for the donation to the library of West Wind, a graceful piece carved from Mexican rosewood. The forty-five-inch sculpture is on permanent exhibit in the Wangenheim Collection of the Central Library.

Hord’s last monumental sculpture, Morning, stands in Embarcadero Marina Park near Seaport Village. The six-foot, three-inch-tall work in black diorite was begun in 1951 but took five years to complete. In fragile health, Hord returned to working with simpler materials: bronzes and terra cotta. But he would continue remarkable productivity, completing one or two major works every year until his death from heart disease at age sixty-three in 1966.