INTRODUCTION

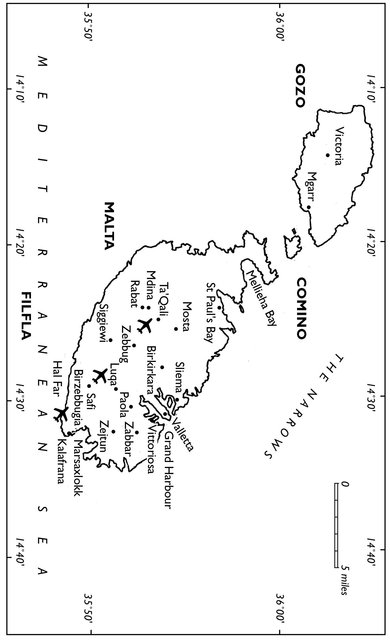

There is something old fashioned about the concept of siege. This is an aspect of warfare that seems more appropriate to the Middle Ages, or even earlier, perhaps to Biblical times, than the twentieth century. Nothing could be further from the truth. The Second World War is regarded by many historians as having introduced so much of the strategy, tactics and technology that features in modern warfare, including the primacy of the aircraft carrier and the submarine and the use of missiles, but siege was once again an important feature of the conflict. Possibly those at Berlin and Singapore can be dismissed as simply being prolonged battles, but Moscow and Stalingrad were worthy of the term siege, particularly the latter after the besieging German Army itself became besieged. More significant was the great siege at Leningrad, lasting almost 900 days. These were all sieges by encircling armies. A completely different kind of siege was endured by those in Malta, not a single island but a small group of islands situated in the Mediterranean, ‘in the middle of the Middle Sea’, almost halfway between Gibraltar and Suez, and conveniently between Europe and North Africa. Malta truly sits at the cross roads of the Mediterranean. For Malta and her people, this was a siege by sea and enforced mainly by air power.

One could argue that Malta was besieged by the Axis Powers from Italy’s entry into the war in June, 1940, to the invasion of Sicily in July, 1943. In fact, it was not until the beginning of 1941 that the siege really began to bite hard, while the beginning of the end came with the successful convoy, known to the Allies as Operation Pedestal, to the Maltese as the Santa Marija Convoy, in August, 1942. By November, 1942, a convoy managed to reach Malta without loss.

Before the war, anticipating Italian involvement, the Air Ministry and the War Office had decided that Malta, just sixty miles south of Sicily, could not be defended, but the Admiralty insisted that it should be, so that it could remain as a base for light forces and for submarines. Malta was seen as being a thorn in the side of the Axis, and so it proved to be. Had Malta been surrendered, perhaps in much the same way as the Channel Islands were, the Italian and, later, the German operations in North Africa would have been so much easier, and Rommel would have been spared the shortages of fuel and water that so hindered his plans to advance to the Suez Canal. In short, defending Malta must have shortened the war in Europe.

The concept of siege was not new to the Maltese, for it bore heavily on their history. They had endured the ‘Great Siege’ by the Ottoman Empire in 1565. The scourge of the Turks was only brought to a standstill by Christendom’s victory in the great naval battle at Lepanto six years later. The Maltese were also used to their country changing hands, having been occupied by the Phoenicians, Romans, Arabs and the French, and then by the British after they had invited them to remove the French in 1799, whereupon the French themselves became besieged in the island’s capital, Valletta, by Maltese insurgents.

During wartime, they were to prove that their association with the British was the more enduring for both nations. No convoys were fought harder, no convoys lost a greater proportion of their ships, than those to Malta. At the height of the conflict, the central Mediterranean became so dangerous that Allied convoys to Egypt had to be re-routed via the Cape of Good Hope and the Suez Canal. The Royal Navy was reduced to using fast minelaying cruisers, such as HMS Welshman and her sister Manxman, and minelaying submarines to enable Malta to survive, but to survive themselves, the submarines had to lie submerged in harbour during the day. The desperate need for fighter aircraft saw two supply trips by the USS Wasp. The need to guard the convoys resulted in the loss of the elderly aircraft carrier HMS Eagle.

Even when ships did reach the Grand Harbour with supplies, the small islands and their small population lacked the facilities to discharge several large ships quickly – a weakness of any convoy system – and ships were sunk before their supplies could be discharged.

That greatest of warships, the fast armoured aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious, which had lived up to her name in the successful attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto, herself came under heavy aerial attack by the Luftwaffe off Malta early in 1941, seeking refuge and emergency repairs in Malta during which time her presence provoked the ‘Illustrious Blitz’.

Despite this, the island did become a base for attacks against the enemy. Most notable was the submarine campaign, including the epic part played by HMS Upholder and her CO, Lieutenant Commander Malcolm Wanklyn, VC, against Italian naval and merchant vessels. Malta-based warships and aircraft soon turned the tables on the Axis, and played their part in the eventual defeat of Rommel’s Afrika Korps. The major blunder by the Axis was the failure to invade, although forces were assembled and plans laid. Instead, the Germans chose to invade Crete, where they suffered such appalling losses, nearly failing in their objective, that Hitler forbade the use of paratroop assaults for at least a year or so. These would have been essential to take Malta given the paucity of good landing beaches and the difficult road access from most of them. In an island of small fields with dry stone walls, there were few locations for glider-landed troops to be set down.

This, then, is the story of Malta’s stand against the Axis powers during the Second World War that led to the award of the George Cross to the island by King George VI.

David Wragg

Edinburgh

January 2003