CHAPTER 7

Reading Comprehension

It can be inferred from the passage that supporters of the Alvarez and Courtillot theories would hold which of the following views in common?

The KT boundary was formed over many thousands of years.

Large animals such as the dinosaurs died out gradually over millions of years.

Mass extinction occurred as an indirect result of debris saturating the atmosphere.

It is unlikely that the specific cause of the Cretaceous extinctions will ever be determined.

Volcanic activity may have been triggered by shock waves from the impact of an asteroid.

Above is a typical Reading Comprehension question. For now, don’t worry that we haven’t given you the passage this question refers to. In this chapter, we’ll look at how to apply the Kaplan Method to this question, discuss the types of questions the GMAT asks about reading passages, and go over the basic principles and strategies that you want to keep in mind on every Reading Comprehension question. But before you move on, take a minute to think about what you see in the structure of this question and answer some questions about how you think it works:

What does it mean to draw an inference from a GMAT passage?

How much are you expected to know about the subject matter of the passages before you take the test?

What can you expect to see in a GMAT passage that discusses two related theories?

What GMAT Core Competencies are most essential to success on this question?

PREVIEWING READING COMPREHENSION

What Does It Mean to Draw an Inference from a GMAT Passage?

You may remember from the Critical Reasoning chapter the definition of an “inference” on the GMAT: an inference is something that must be true, based on the information provided. There are two important parts to this definition:

(1) A valid GMAT inference must be true. This sets a high standard for what you consider a valid inference. It is sometimes difficult to determine whether a statement in an answer choice must always be true, but you can also approach these questions by eliminating the four answer choices that could be false. Keep both of these tactics in mind for questions that ask for an inference.

(2) A valid GMAT inference is based on the passage. By definition, an inference won’t be explicitly stated in the passage; you will have to understand the passage well enough to read between the lines. But just because it isn’t directly stated doesn’t mean an inference could be anything under the sun. On the GMAT, any inference you draw will be unambiguously supported by something that is stated in the passage. It may take some Critical Thinking to figure out, but you will always be able to pinpoint exactly why a valid inference must be true.

How Much Are You Expected to Know about the Subject Matter of the Passages before You Take the Test?

Familiarity with the subject matter is not required. GMAT passages contain everything you need to answer GMAT questions. In fact, many Reading Comp questions contain wrong answer choices based on information that is actually true but not mentioned in the passage. So if you know the subject, be careful not to let your prior knowledge influence your answer. And if you don’t know the subject, be happy—some wrong answer traps won’t be tempting to you!

Reading Comprehension is designed to test not your prior knowledge but your critical reading skills. Among other things, it tests whether you can do the following:

Summarize the main idea of a passage.

Understand logical relationships between facts and concepts.

Make inferences based on information in a text.

Analyze the logical structure of a passage.

Deduce the author’s tone and attitude about a topic from the text.

Note that none of these objectives relies on anything other than your ability to understand and apply ideas found in the passage. This should be a comforting thought: everything you need is right there in front of you. In this chapter, you will learn strategic approaches to help you make the best use of the information the testmakers provide.

What Can You Expect to See in a GMAT Passage That Discusses Two Related Theories?

Because the GMAT cannot ask you purely factual questions that might reward or punish you for your outside knowledge, it tends to focus its questions on the opinions or analyses contained in the passages. Since this question asks you what Alvarez’s and Courtillot’s theories have in common, this means that they must agree on at least one thing. You can anticipate, however, that the two theories are largely not in agreement with each other.

This is a common structure for a GMAT passage: the author discusses more than one explanation of the same phenomenon, describing each in turn or perhaps comparing them directly, usually summarizing the relevant evidence and explaining why disagreement exists among the explanations’ proponents. When a passage contains multiple opinions, keep track of who is making each assertion and how the assertion relates to the other opinions in the passage: does it contradict, agree with, or expand upon what came before? Another important thing to note is whether the author takes a side—does the author prefer one viewpoint to another? Does he offer his own competing argument?

What GMAT Core Competencies Are Most Essential to Success on This Question?

Since the GMAT constructs Reading Comprehension passages in similar ways and asks questions that conform to predictable “types,” you can learn to anticipate how an author will express her ideas and what the GMAT testmakers will ask you about a passage. The more you practice and the more you focus on structure as you read, the stronger your Pattern Recognition skills will become.

Critical Thinking is also essential. As you read, you should ask yourself why the author is including certain details and what the author’s choice of transitional keywords implies about how the ideas in the passage are related.

The best test takers learn how to pay Attention to the Right Detail. Reading Comp passages are typically filled with more details than you could reasonably memorize—and more, in fact, than you will ever need to answer the questions. Since time is limited, you must prioritize the information you assimilate from the passage, focusing on the big picture but allowing yourself to return to the passage to research details as needed.

Practice Paraphrasing constantly as you read, both to keep yourself engaged and to make sure you understand what’s being discussed. Developing this habit will make taking notes much easier, since you’ve already distilled and summarized the most important information in your head. You’ll learn later in this chapter how to take concise and well-organized notes in the form of a Passage Map.

Here are the main topics we’ll cover in this chapter:

Question Format and Structure

The Basic Principles of Reading Comprehension

The Kaplan Method for Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension Question Types

QUESTION FORMAT AND STRUCTURE

The directions for Reading Comprehension questions look like this:

Directions: The questions in this group are based on the content of a passage. After reading the passage, choose the best answer to each question. Base your answers only according to what is stated or implied in the text.

In Reading Comp, you are presented with a reading passage (in an area of business, social science, biological science, or physical science) and then asked three or four questions about that text. You are not expected to be familiar with any topic beforehand—all the information you need is contained in the text in front of you. In fact, if you happen to have some previous knowledge about a given topic, it is important that you not let that knowledge affect your answers. Naturally, some passages will be easier to understand than others, though each will present a challenge. The passages will have the tone and content that one might expect from a scholarly journal.

You will see four Reading Comp passages—most likely two shorter passages with 3 questions each and two longer passages with 4 questions each, for a total of approximately 14 questions. However, as is usual for the computer-adaptive GMAT, you will see only one question at a time on the screen, and you will have to answer each question before you can see the next question. The passage will appear on the left side of the screen. It will remain there until you’ve answered all of the questions that relate to it. If the text is longer than the available space, you’ll be given a scroll bar to move through it. Plan to take no longer than 4 minutes to read and make notes on the passage and a little less than 1.5 minutes to answer each question associated with the passage.

TAKEAWAYS: QUESTION FORMAT AND STRUCTURE

GMAT passages are between one and five paragraphs in length.

You will usually see two shorter and two longer passages in the Verbal section.

Usually, you will get three questions for a shorter passage and four questions for a longer passage. You can answer only one at a time and can’t go back to previous questions.

The passages usually have the tone and content that one might expect from a scholarly journal.

You are not expected to have prior knowledge of the subject matter in the passage.

The passage stays on the screen for all questions that pertain to it.

You should spend 4 minutes per passage and a little less than 1.5 minutes per question.

THE BASIC PRINCIPLES OF READING COMPREHENSION

In daily life, most people read to learn something or to pass the time pleasantly. Neither of these goals has much to do with the GMAT. On Test Day, you have a very specific goal—to get as many right answers as you can. So your reading needs to be tailored to that goal. There are really only two things a Reading Comp question can ask you about: the “big picture” of the passage or its “little details.”

Since the passage is right there on the screen, you don’t need to worry much about the “little details” as you read. (In fact, doing so may hinder your ability to answer questions, as you’ll soon see.) So your main goal as you read is to prepare yourself to get the “big-picture” questions right, while leaving yourself as much time as possible to find the answers to the “little-detail” questions.

Here are the four basic principles you need to follow to accomplish this goal.

Look for the Topic and Scope of the Passage

Think of the topic as the first big idea that comes along. Almost always, it will be right there in the first sentence. It will be something broad, far too big to discuss in the 150–350 words that most GMAT passages contain. Here’s an example of how a passage might begin:

The great migration of European intellectuals to the United States in the second quarter of the 20th century prompted a transmutation in the character of Western social thought.

What’s the topic? The migration of European intellectuals to the United States in the second quarter of the 20th century. It would also be okay to say that the topic is the effects of that migration on Western social thought. Topic is a very broad concept, so you really don’t need to worry about how exactly you word it. You just need to get a good idea of what the passage is talking about so you feel more comfortable reading.

Now, as to scope. Think of scope as a narrowing of the topic. You’re looking for an idea that the author might reasonably focus on for the length of a GMAT passage. If the topic is “the migration of European intellectuals to the United States in the second quarter of the 20th century,” then perhaps the scope will be “some of the effects of that migration upon Western social thought.” It will likely be even more specific: “one aspect of Western social thought affected by the migration.” But perhaps something unexpected will come along. Might the passage compare two different migrations? Or contrast two different effects? Think critically about what’s coming and look for clues in the text that let you know on what specific subject(s) the author intends to focus.

Finding the scope is critically important to doing well on Reading Comp. Many Reading Comp wrong answers are wrong because the information that would be needed to support them is simply not present in the passage. It’s highly unlikely that there will be a “topic sentence” that lays out plainly what the author intends to write about—but the first paragraph probably will give some indication of the focus of the rest of the passage.

Note that some passages are only one paragraph long. In these cases, the topic can still appear in the first sentence. The passage will probably (but not necessarily) narrow in scope somewhere in the first third of the paragraph, as the author doesn’t have much text to work with and needs to get down to business quickly.

Get the Gist of Each Paragraph and Its Structural Role in the Passage

The paragraph is the main structural unit of any passage. At first, you don’t yet know the topic or scope, so you have to read the first paragraph pretty closely. But once you get a sense of where the passage is going, all you need to do is understand what role each new paragraph plays. Ask yourself the following:

Why did the author include this paragraph?

What’s discussed here that’s different from the content of the paragraph before?

What bearing does this paragraph have on the author’s main idea?

What role do the details play?

Notice that last question—don’t ask yourself, “What does this mean?” but rather, “Why is it here?” Many GMAT passages try to swamp you with tedious, dense, and sometimes confusing details. Consider this paragraph, which might appear as part of a difficult science-based passage:

The Burgess Shale yielded a surprisingly varied array of fossils. Early chordates were very rare, but there were prodigious numbers of complex forms not seen since. Hallucigenia, so named for a structure so bizarre that scientists did not know which was the dorsal and which the ventral side, had fourteen legs. Opabinia had five eyes and a long proboscis. This amazing diversity led Gould to believe that it was highly unlikely that the eventual success of chordates was a predictable outcome.

This is pretty dense stuff. But if you don’t worry about understanding all of the science jargon and instead focus on the gist of the paragraph and why the details are there, things get easier. The first sentence isn’t that bad:

The Burgess Shale yielded a surprisingly varied array of fossils.

A quick paraphrase is that the “Burgess Shale,” whatever that is, had a lot of different kinds of fossils. The passage continues:

Early chordates were very rare, but there were prodigious numbers of complex forms not seen since. Hallucigenia, so named for a structure so bizarre that scientists did not know which was the dorsal and which the ventral side, had fourteen legs. Opabinia had five eyes and a long proboscis.

When you read this part of the passage strategically, asking what its purpose is in context, you see that this is just a list of the different kinds of fossils and some facts about them. There were not a lot of “chordates,” whatever they are, but there was lots of other stuff.

This amazing diversity led Gould to believe that it was highly unlikely that the eventual success of chordates was a predictable outcome.

Notice that the beginning of this sentence tells us why those intimidatingly dense details are there; they are the facts that led Gould to a belief—namely that the rise of “chordates” couldn’t have been predicted. So, on your noteboard, you’d jot down something like this:'

Evidence for Gould’s belief—chordate success not predictable.

Notice that you don’t have to know what any of these scientific terms mean in order to know why the author brings them up. Taking apart every paragraph like this allows you to create a map of the passage’s overall structure. We’ll call this a “Passage Map” from here on—we’ll discuss Passage Mapping in detail later in this chapter. Making a Passage Map will help you acquire a clear understanding of the “big picture.” It will give you a sense of mastery over the passage, even when it deals with a subject you don’t know anything about.

To break down paragraphs and understand the structural function of each part, look for keywords, or structural words or phrases that link ideas to one another. You got an overview of the categories of keywords in the Verbal Section Overview chapter of this book. Let’s now dig a little deeper into how keywords can help you distinguish the important things (such as opinions) from the unimportant (such as supporting examples) and to understand why the author wrote each sentence.

Types of keywords:

Contrast keywords such as but, however, nevertheless, and on the other hand tell you that a change or disagreement is coming.

Continuation keywords such as moreover, also, and furthermore tell you that the author is continuing on the same track or general idea.

Logic keywords, which you’ve seen to be very important in Critical Reasoning stimuli, alert you to an author’s reasoning. Evidence keywords let you know that something is being offered in support of a particular idea. The specifics of the support are usually unimportant for the first big-picture read, but you do want to know what the idea is. Examples of evidence keywords are since, because, and as. Conclusion keywords such as therefore and hence are usually not associated with the author’s main point in Reading Comp. Rather, they indicate that the next phrase is a logical consequence of the sentence(s) that came before.

Illustration keywords let you know that what follows is an example of a broader point. One example, of course, is example. For instance is another favorite in GMAT passages.

Sequence/Timing is a broader category of keywords. These are any words that delineate lists or groupings. First, second, and third are obvious examples. But you could also get a chronological sequence (17th century, 18th century, and today). Science passages may also group complicated phenomena using simpler sequence keywords (at a high temperature and at a low temperature, for example).

Emphasis and Opinion keywords can be subtler than those in the other categories, but these are perhaps the most important keywords of all. Emphasis keywords are used when the author wants to call attention to a specific point. These come in two varieties: generic emphasis keywords, such as very and critical, and charged emphasis keywords, such as beneficial or dead end. Opinion keywords point to the ideas in a passage; these opinions are frequently the focus of GMAT questions. Be sure to distinguish between the author’s opinions and those of others. Others’ opinions are easier to spot and will be triggered by words such as believe, theory, or hypothesis. The author’s opinion is more likely to reveal itself in words that imply a value judgment, such as valid or unsupported. (If the passage expresses something in the first person, such as I disagree, that’s also a clear sign.)

As you might have guessed, reading the passage strategically doesn’t mean simply going on a scavenger hunt for keywords. Rather, it means using those keywords to identify the important parts of the passage—its opinions and structure—so you can focus on them and not on little details. Keywords also help you predict the function of the text that follows. Let’s see how this works by taking a look at a simple example. Say you saw a passage with the following structure on Test Day. What kinds of details can you anticipate would fill each of the blanks?

You learn about Bob’s attitude toward East Main State Business School through the word excited, which is an emphasis keyword. After because (a logic keyword) will be a reason that East Main State is a great place to go to school or some reason it’s special to Bob. After furthermore and moreover (continuation keywords) will be additional reasons or elaborations of the reason in the first sentence. After however will come some drawback or counterexample that undermines the previous string of good things about East Main State. You may not be able to predict the exact content of the details that fill the blanks, but you can predict the tone and purpose of the details. Reading this way is valuable because the GMAT testmakers are more likely to ask you why the author put the details in, not what’s true about them.

Reading for keywords seems straightforward when the passage deals with subject matter that’s familiar or easy to understand. But what if you were to see the following passage about a less familiar topic? How can you decode the structure of the following paragraph?

Here the emphasis keyword important lets you know why the author cares about mirror neurons: they’re important for learning. The details that would fill these blanks are probably dense and intimidating for the non-neurologist, but the strategic reader will still be able to understand the passage well enough to answer the questions correctly. Notice that the structure is identical to the paragraph about Bob, so the details that fill the blanks will serve the same purpose as those you predicted previously. You can anticipate what they will be and why the author is including them. Reading strategically allows you to take control of the passage; you will know where the author is going and what the GMAT will consider important, even if you know nothing about the subject matter of the passage.

Look for Opinions, Theories, and Points of View—Especially the Author’s

An important part of strategic reading is distinguishing between factual assertions and opinions or interpretations. It’s the opinions and interpretations that Reading Comp questions are most often based on, so you should pay the most attention to them. Let’s say you come upon a paragraph that reads:

The coral polyps secrete calcareous exoskeletons, which cement themselves into an underlayer of rock, while the algae deposit still more calcium carbonate, which reacts with sea salt to create an even tougher limestone layer. All of this accounts for the amazing renewability of the coral reefs despite the endless erosion caused by wave activity.

In a sense, this is just like the Burgess Shale paragraph; it begins with a lot of scientific jargon and later tells us why that jargon is there. In this case, it shows us how coral reefs renew themselves. But notice a big difference—the author doesn’t tell us how someone else interprets these facts. He could have written “scientists believe that these polyps account for …,” but he didn’t. This is the author’s own interpretation.

It’s important to differentiate between the author’s own voice and other people’s opinions. GMAT authors may disagree with other people but won’t contradict themselves. So the author of the Burgess Shale passage might well disagree with Gould in the next paragraph. But the author of the Coral Reef passage has laid his cards on the table—he definitely thinks that coral polyps and algae are responsible for the renewability of coral reefs.

Spotting the opinions and theories also helps you to accomplish the goal of reading for structure. Once you spot an idea, you can step back from the barrage of words and use Critical Thinking to dissect the passage, asking, “Why is the author citing this opinion? Where’s the support for this idea? Does the author agree or disagree?”

Consider how you would read the following paragraph strategically:

Abraham Lincoln is traditionally viewed as an advocate of freedom because he issued the Emancipation Proclamation and championed the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended legal slavery in the United States. And indeed this achievement cannot be denied. But he also set uncomfortable precedents for the curtailing of civil liberties.

A strategic reader will zero in on the passage’s keywords and analyze what each one reveals about the structure of the passage and the author’s point of view. Here the keyword traditionally lets you know how people usually think about Lincoln. You might already anticipate that the author is setting up a contrast between the traditional view and her own. Sure enough, the keyword but makes the contrast clear: the author asserts that despite his other accomplishments, Lincoln in fact restricted civil liberties. And the word uncomfortable is an opinion keyword indicating that the author is not at all pleased with Lincoln because of it. However, the author already tempered her criticism with the phrase this achievement cannot be denied, meaning that she won’t go so far as to say that Lincoln was an enemy of freedom.

At this point, the strategic reader can anticipate where the passage’s structure will lead, just as you did on the earlier passages dealing with Bob at East Main State and mirror neurons. Given how this opening paragraph ends, you can predict that the author will spend at least one paragraph describing these “uncomfortable precedents” and how they restricted civil liberties. It might even be possible, since she uses the word precedents, that she goes on to describe how later governments or leaders used Lincoln’s actions as justification for their own restrictions.

This is the power of predictive, strategic reading: by using keywords to anticipate where the author is heading, you will not only stay more engaged as you read, but you’ll also develop a better understanding of the structure of the passage and the author’s point of view—the very things that pay off in a higher GMAT score.

Put together, the passage’s structure and the opinions and theories it contains will lead you to understand the author’s primary purpose in writing the passage. This is critical, as most GMAT passages have a question that directly asks for that purpose. For the Lincoln passage, you might get a question like this:

Which of the following best represents the main idea of the passage?

The Emancipation Proclamation had both positive and negative effects.

Lincoln’s presidency laid the groundwork for future restrictions of personal freedoms.

The traditional image of Lincoln as a national hero must be overturned.

Lincoln used military pressure to influence state legislatures.

Abraham Lincoln was an advocate of freedom.

Just from a strategic reading of the first few sentences, you could eliminate (A) as being a distortion of the first and third sentences, (C) as being too extreme because of the cannot be denied phrase, (D) as irrelevant—either too narrow or just not present in the passage at all, and (E) as missing the author’s big point—that Lincoln helped restrict civil liberties. And just like that, you can choose (B) as the right answer and increase your score.

Don’t Obsess over Details

On the GMAT, you’ll need to read only for short-term—as opposed to long-term—retention. When you finish the questions about a certain passage, that passage is over and done with. You’re promptly free to forget everything about it.

What’s more, there’s certainly no need to memorize—or even fully comprehend—details. You do need to know why they are there so that you can answer big-picture questions, but you can always go back and reread them in greater depth if you’re asked a question that hinges on a detail. And you’ll find that if you have a good sense of the passage’s scope and structure, the ideas and opinions in the passage, and the author’s purpose, then you’ll have little problem navigating through the text as the need arises.

Furthermore, you can even hurt your score by reading the details too closely. Here’s how:

Wasted time. Remember, there will only be three or four questions per passage. The testmakers can’t possibly ask you about all the little details. So don’t waste your valuable time by focusing on minutiae you will likely not need to know. If you do, you won’t have nearly enough time to deal with the questions.

Tempting wrong answers. Attempting to read and understand fully every last detail can cause your mind to jumble all the details—relevant and irrelevant alike—together in a confusing mess. Since most of the wrong answers in GMAT Reading Comp are simply distortions of details from the passage, they will sound familiar and therefore be tempting to uncritical readers. The strategic reader doesn’t give those details undue importance and thus isn’t tempted by answer choices that focus on them. Instead, he takes advantage of the open-book nature of the test to research specific details only when asked.

Losing the big picture. It’s very easy to miss the forest for the trees. If you get too drawn into the small stuff, you can pass right by the emphasis and opinion keywords that you’ll need to understand the author’s main purpose.

Here’s a great trick for cutting through confusing, detail-laden sentences: focus on the subjects and verbs first, throwing away modifying phrases, and don’t worry about fancy terminology. Let’s revisit some dense text from before:

The coral polyps secrete calcareous exoskeletons, which cement themselves into an underlayer of rock, while the algae deposit still more calcium carbonate, which reacts with sea salt to create an even tougher limestone layer. All of this accounts for the amazing renewability of the coral reefs despite the endless erosion caused by wave activity.

Now look at what happens if you paraphrase these sentences, distilling them to main subjects and verbs, ignoring modifiers, and not worrying about words you don’t understand:

Coral polyps (whatever they are) secrete something … and algae deposit something. This accounts for the amazing renewability of the coral reefs.

The structure of this paragraph has suddenly become a lot more transparent. Now the bulkiness of that first sentence won’t slow you down, so you can understand its role in the big picture.

TAKEAWAYS: THE BASIC PRINCIPLES OF READING COMPREHENSION

The basic principles of Reading Comprehension are the following:

Look for the topic and scope of the passage.

Get the gist of each paragraph and its structural role in the passage.

Look for opinions, theories, and points of view—especially the author’s.

Don’t obsess over details.

Let’s now put all these basic principles together to analyze a passage similar to one you may see on Test Day. However, unlike passages you’ll see on Test Day, the following text has been formatted to approximate the way a strategic reader might see it—important keywords and phrases are in bold, the main ideas are in normal type, and the supporting details are grayed out. Take a moment to read only the bold and regular text: identify what the keywords tell you about the structure, paraphrase the crucial text, and practice predicting what the grayed-out portions contain.

The United States National Park Service (NPS) is in the unenviable position of being charged with two missions that are frequently at odds with one another. Created by an act of Congress in 1916, the NPS is mandated to maintain the country’s national parks in “absolutely unimpaired” condition, while 5somehow ensuring that these lands are available for “the use … and pleasure of the people.” As the system of properties (known as units) managed by the NPS has grown over the years—a system now encompassing seashores, battlefields, and parkways—so has its popularity with the vacationing public. Unfortunately, the maintenance of the system has not kept pace with the record number of visits, and many of the 10properties are in serious disrepair.

Several paths can be taken, perhaps simultaneously, to alleviate the deterioration of the properties within the system. Adopting tougher requirements for admission could reduce the number of additional units that the NPS manages. Congress has on occasion added properties without any input from the NPS itself. 15It is debatable whether all of these properties, which may be of importance to the constituents of individual representatives of Congress, pass the test of “national significance.” Furthermore, some of the units now in the NPS (there are close to 400) receive few visitors, and there is no reason to think that this trend will reverse itself. These units can be removed from the system, and their fates can 20be decided by local public and private concerns. The liberated federal funds could then be rerouted to areas of greater need within the system.

Another approach would be to attack the root causes of the deterioration. Sadly, a great deal of the dilapidated condition of our national parks and park lands can be attributed not to overuse, but to misuse. Visitors should be educated about 25responsible use of a site. Violators of these rules must be held accountable and fined harshly. There are, of course, already guidelines and penalties set in place, but studies strongly indicate that enforcement is lax.

From the first sentence, you can already tell a lot about this passage. The Park Service has an “unenviable” (opinion keyword) dilemma. You can predict that the author will state (in the grayed-out text of the first paragraph) what that dilemma is.

You get more opinion from the author in the final sentence of paragraph 1. “Unfortunately,” (opinion keyword), the Park Service can’t maintain the parks with so many visitors. The problem is apparently “serious” (emphasis keyword). On Test Day you would jot some brief notes on your noteboard about the main idea of the first paragraph:

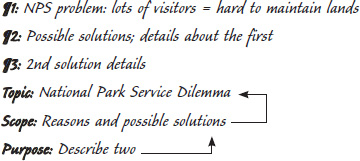

¶1: NPS problem: lots of visitors = hard to maintain lands

From the first sentence of the second paragraph, where do you anticipate that this passage will go? The phrase “alleviate the deterioration” indicates that the author will discuss some possible solutions to the Park Service’s problem. Now is a good time to ask yourself whether this author is likely to express a preference for one of those solutions in particular. It seems that this author will probably describe the solutions without supporting one over the others, since she says there are “several” and that they might work at the same time. In the middle of the second paragraph, the word “Furthermore” is a continuation keyword, signaling that the paragraph continues to describe a proposed solution and why it might be effective. This is all you need to know about this paragraph from your initial read-through. Take down some notes for later reference:

¶2: Possible solutions; details about the first

Right off the bat, the third paragraph indicates that the author will describe “another approach.” If you need to know details about this other approach, you can always return to the passage to research the answer to a question.

¶3: 2nd solution details

Just from this quick analysis, notice how much you already understand about the structure of the passage and the author’s point of view. You effectively know what the grayed-out parts of the passage accomplish, even though you can’t recite the details they contain. You are now in a strong position to approach the questions that accompany this passage, knowing that you can always return to the passage to clarify your understanding of any relevant details. Let’s look at this first question:

Which of the following best describes the organization of the passage as a whole?

The author mentions a problem, and opposing solutions are then described.

The various factors that led to a problem are considered, and one factor is named the root cause.

A historical survey is made of an institution, followed by a discussion of the problem of management of the institution.

A problem is described, and two possibly compatible methods for reducing the problem are then outlined.

A description of a plan and the flaws of the plan are delineated.

This question asks for the organization of the entire passage. Fortunately, you already have the passage structure in your notes, so there’s no need to go back to the passage itself to answer this question. The author begins by introducing a problem, then advances two potential solutions to that problem. The solutions are complementary, as the author states in line 11 that they can be undertaken “simultaneously.” Choice (D) matches this prediction and is the correct answer.

If you weren’t sure about the answer, you could always eliminate incorrect answer choices by finding the specific faults they contain. (A) cannot be correct because it calls the two solutions “opposing.” (B) is incorrect because the focus of the passage is not on the “factors” leading to the problem but rather on solutions to the problem. (C) is incorrect because the passage gives no “historical survey” of the National Park Service; the only bit of historical data given is the date of its founding (1916). Finally, (E) is incorrect because the passage does not focus on the strengths and drawbacks of a single proposed plan of action; instead, it considers several different suggestions. Moreover, the passage never discusses the flaws of any of these possible solutions. Choice (D) is correct.

Let’s now look at one more question about this passage:

The author is primarily concerned with

analyzing the various problems that beset the NPS

summarizing the causes of deterioration of NPS properties

criticizing the NPS’s maintenance of its properties

encouraging support for increased funding for the NPS

discussing possible solutions for NPS properties’ deterioration

This question asks for the author’s purpose in writing the passage. As was the case in the previous question, you’ve already thought through the author’s purpose as you read the passage strategically. Again, this question does not require specific research beyond the notes you’ve already taken.

The author is concerned with advancing two possible solutions to the dilemma faced by the National Park Service. Choice (E) matches your prediction perfectly and is correct.

(A) is incorrect because only one problem is discussed, not “various” problems. (B) is incorrect because it is the solutions, not the causes, of the National Park Service’s problem that are the focus of the passage. (C) is incorrect because the author is not critical of the NPS. Indeed, the word “unenviable” in the first sentence actually signals sympathy with the NPS’s plight. (D) is incorrect because there is no discussion of funding in the passage. (E) is the correct answer.

THE KAPLAN METHOD FOR READING COMPREHENSION

Many test takers read the entire passage closely from beginning to end, taking detailed notes and making sure that they understand everything, and then try to answer the questions from memory. But this is not what the best test takers do.

The best test takers attack the passages and questions critically in the sort of aggressive, energetic, and goal-oriented way you’ve learned earlier. Working this way pays off because it’s the kind of pragmatic and efficient approach that the GMAT rewards—the same type of approach that business schools like their students to take when faced with an intellectual challenge.

The Kaplan Method for Reading Comprehension |

|

1. Read the passage strategically. 2. Analyze the question stem. 3. Research the relevant text. 4. Make a prediction. 5. Evaluate the answer choices. |

To help this strategic approach become second nature to you, Kaplan has developed a Method that you can use to attack each and every Reading Comp passage and question.

Step 1: Read the Passage Strategically

Like most sophisticated writing, the prose you will see on the GMAT doesn’t explicitly reveal its secrets. Baldly laying out the why and how of a passage up front isn’t a hallmark of GMAT Reading Comprehension passages. And even more important (as far as the testmakers are concerned), if the ideas were blatantly laid out, the testmakers couldn’t ask probing questions about them. So to set up the questions—to test how you think about the prose you read—the GMAT uses passages in which authors hide or disguise their reasons for writing and challenge you to extract them.

This is why it’s essential to start by reading the passage strategically, staying on the lookout for structural keywords and phrases. With this strategic analysis as a guide, you should construct a Passage Map—a brief summary of each paragraph and its function in the passage’s structure. You should also note the author’s topic, scope, and purpose. Start by identifying the topic and then hunt for scope, trying to get a sense of where the passage is going, what the author is going to focus on, and what role the first paragraph is playing. As you finish reading each paragraph, jot down a short note about its structure and the role it plays in the passage. This process is similar to how you took notes on each paragraph of the National Park Service passage above. When you finish reading the passage, double-check that you got the topic and scope right (sometimes passages can take unexpected turns) and note the author’s overall purpose.

The topic will be the first big, broad idea that comes along. Almost always, it will be right there in the first sentence. There’s no need to obsess over exactly how you word the topic; you just want a general idea of what the author is writing about so the passage gets easier to understand.

The scope is the narrow part of the topic that the author focuses on. If the author expresses his own opinion, then the thing he has an opinion about is the scope. Your statement of the scope should be as narrow as possible while still reflecting the passage as a whole. Your scope statement should also answer the question “What about this topic interests the author?” Identifying the scope is crucial because many wrong answers are unsupported by the facts the author has actually chosen to provide. Remember that even though the first paragraph usually narrows the topic down to the scope, there probably won’t be a “topic sentence” in the traditional sense.

The purpose is what the author is seeking to accomplish by writing the passage. You’ll serve yourself well by picking an active verb for the purpose. Doing so helps not only by setting you up to find the right answer—many answer choices contain active verbs—but also by forcing you to consider the author’s opinion. Here are some verbs that describe the purpose of a “neutral” author: describe, explain, compare. Here are some verbs for an “opinionated” author: advocate, argue, rebut, analyze.

After you finish reading, your Passage Map should look something like this example:

You don’t want to take any more than four minutes to read and write your Passage Map. After all, you get points for answering questions, not for creating nicely detailed Passage Maps. The more time you can spend working on the questions, the better your score will be. But creating a Passage Map and identifying the topic, scope, and purpose will prepare you to handle those questions efficiently and accurately.

It generally works best to create your Passage Map paragraph by paragraph. Don’t write while you’re reading, since you’ll be tempted to write too much. But it’s also not a good idea to wait until you’ve read the whole passage before writing anything, since it will be more difficult for you to recall what you’ve read. Analyze the structure as you read and take a few moments after you finish each paragraph to summarize the main points. Include details that are provided as evidence only when keywords indicate their importance. A line or two of paraphrase is generally enough to summarize a paragraph.

Your Passage Map can be as elaborate or as brief as you need it to be. Don’t waste time trying to write out entire sentences if fragments and abbreviations will do. And notice in the above example how effective arrows can be. For example, there’s no sense writing out the purpose as “Describe two solutions to the National Park Service’s dilemma resulting from the dual imperative to keep lands unimpaired and also to allow for their recreational use,” when some simple notes with arrows are just as helpful to you.

Step 2: Analyze the Question Stem

Only once you have read the passage strategically and jotted down your Passage Map should you read the first question stem. The second step of the Kaplan Method is to identify the question type; the most common question types are Global, Detail, Inference, and Logic. We will cover each of these question types in detail later in this chapter. For now, know that you will use this step to ask yourself, “What should I do on this question? What is being asked?” Here are some guidelines for identifying each of the main question types:

Global. These question stems contain language that refers to the passage as a whole, such as “primary purpose,” “main idea,” or “appropriate title for the passage.”

Detail. These question stems contain direct language such as “according to the author,” “the passage states explicitly,” or “is mentioned in the passage.”

Inference. These question stems contain indirect language such as “most likely agree,” “suggests,” or “implies.”

Logic. These question stems ask for the purpose of a detail or paragraph and contain language such as “in order to,” “purpose of the second paragraph,” or “for which of the following reasons.”

In addition to identifying the question type, be sure to focus on exactly what the question is asking. Let’s say you see this question:

The passage states which of the following about the uses of fixed nitrogen?

Don’t look for what the passage says about “nitrogen” in general. Don’t even look for “fixed nitrogen” alone. Look for the uses of fixed nitrogen. (And be aware that the GMAT may ask you to recognize that application is a synonym of use.)

Finally, the GMAT occasionally asks questions that do not fall into one of the four major categories. These outliers make up only about 8 percent of GMAT Reading Comp questions, so you will probably see only one such question or maybe none at all. If you do see one, don’t worry. These rare question types usually involve paraphrasing or analyzing specific points of reasoning in the passage. Often they are extremely similar to question types you know from GMAT Critical Reasoning. Because you can use your Passage Map to understand the passage’s structure and Kaplan’s strategies for Critical Reasoning to deconstruct the author’s reasoning, you will be prepared to handle even these rare question types.

Step 3: Research the Relevant Text

Since there just isn’t enough time to memorize the whole passage, you shouldn’t rely on your memory to answer questions. Treat the GMAT like an open-book test, knowing you can return to the passage as needed. However, don’t let that fact make you overreliant on research in the passage. Doing so could lead to lots of rereading and wasted time. For some question types, you are just as likely to find all the information you need to answer the question correctly using only your Passage Map. Here is how you should focus your research for each question type:

Global. The answer will deal with the passage as a whole, so you should review your Passage Map and the topic, scope, and purpose you noted.

Detail. Use the specific reference in the question stem to research the text. Look for the detail to be associated with a keyword.

Inference. For questions that include specific references, research the passage based on the clues in the question stem. For open-ended questions, refer to your topic, scope, and purpose; you may need to research in the passage as you evaluate each answer choice.

Logic. Use the specific reference in the question stem to research the text. Use keywords to understand the passage’s structure. Refer to your Passage Map for the purpose of a specific paragraph.

Step 4: Make a Prediction

As you have seen in the Critical Reasoning chapter of this book, predicting the answer before you look at the answer choices is a powerful strategy to increase your efficiency and accuracy. The same is true for GMAT Reading Comp. Making a prediction allows you to know what you’re looking for before you consider the answer choices. Doing so will help the right answer jump off the screen at you. It will also help you avoid wrong answer choices that might otherwise be tempting. Here is how you should form your prediction for each question type:

Global. Use your Passage Map and topic, scope, and purpose as the basis of your prediction.

Detail. Predict an answer based on what the context tells you about the detail.

Inference. Remember that the right answer must be true based on the passage. (Since many valid inferences could be drawn from even one detail, it’s often best not to make your prediction more specific than that.)

Logic. Predict an answer that focuses on why the paragraph or detail was used, not on what it says.

Step 5: Evaluate the Answer Choices

Hunt for the answer choice that matches your prediction. If only one choice matches, it’s the right answer.

If you can’t find a match for your prediction, if more than one choice seems to fit your prediction, or if you weren’t able to form a prediction at all (this happens for some open-ended Inference questions), then you’ll need to evaluate each answer choice, looking for errors. If you can prove four answers wrong, then you can confidently select the one that remains, even if you aren’t completely sure what you think about it. This is the beauty of a multiple-choice test—knowing how to eliminate the four wrong answers is as good as knowing how to identify the correct one.

Here are some common wrong answer traps to look out for:

Global. Answers that misrepresent the scope or purpose of the passage and answers that focus too heavily on details from one part of the passage

Detail. Answers that distort the context or focus on the wrong details entirely

Inference. Answers that include extreme language or exaggerations of the author’s statements, distortions of the passage’s meaning, or the exact opposite of what might be inferred

Logic. Answers that get the specifics right but the purpose wrong

Look out for unsupported answer choices and for “half-right/half-wrong” choices, which are fine at the beginning but then take a wrong turn. Some answer choices are very tempting because they have the correct details and the right scope, but they have a not, doesn’t, or other twist that flips their meanings to the opposite of what the question asks for. Watch out for these “180s.”

Now let’s apply the Kaplan Method to an actual GMAT-length passage and some of its questions. One of the questions that follow is the same one you saw at the beginning of the chapter. Read the passage strategically and practice making a Passage Map. You can try your hand at the questions and then compare your analysis to ours, or you can let our analysis below guide you through the steps of the Kaplan Method. For now, don’t worry if you’re not quite sure how to identify the question types; we will cover those thoroughly later in this chapter. For now, concentrate on analyzing what the question asks of you and using the Method to take the most efficient path from question to correct answer.

Questions 1–2 are based on the following passage

Since 1980, the notion that mass extinctions at the end of the Cretaceous period 65 million years ago resulted from a sudden event has slowly gathered support, although even today there is no scientific consensus. In the Alvarez scenario, an asteroid struck the earth, creating a gigantic crater. Beyond the immediate effects 5of fire, flood, and storm, dust darkened the atmosphere, cutting off plant life. Many animal species disappeared as the food chain was snapped at its base.

Alvarez’s main evidence is an abundance of iridium in the KT boundary, a thin stratum dividing Cretaceous rocks from rocks of the Tertiary period. Iridium normally accompanies the slow fall of interplanetary debris, but in KT boundary 10strata, iridium is 10–100 times more abundant, suggesting a rapid, massive deposition. Coincident with the boundary, whole species of small organisms vanish from the fossil record. Boundary samples also yield osmium isotopes, basaltic sphericles, and deformed quartz grains, all of which could have resulted from high-velocity impact.

15Paleontologists initially dismissed the theory, arguing that existing dinosaur records showed a decline lasting millions of years. But recent studies in North America, aimed at a comprehensive collection of fossil remnants rather than rare or well-preserved specimens, indicate large dinosaur populations existing immediately prior to the KT boundary. Since these discoveries, doubts about 20theories of mass extinction have lessened significantly.

Given the lack of a known impact crater of the necessary age and size to fit the Alvarez scenario, some scientists have proposed alternatives. Courtillot, citing huge volcanic flows in India coincident with the KT boundary, speculates that eruptions lasting many thousands of years produced enough atmospheric debris to cause 25global devastation. His analyses also conclude that iridium in the KT boundary was deposited over a period of 10,000–100,000 years. Alvarez and Asaro reply that the shock of an asteroidal impact could conceivably have triggered extensive volcanic activity. Meanwhile, exploration at a large geologic formation in Yucatan, found in 1978 but unstudied until 1990, has shown a composition consistent with 25extraterrestrial impact. But evidence that the formation is indeed the hypothesized impact site remains inconclusive.

It can be inferred from the passage that supporters of the Alvarez and Courtillot theories would hold which of the following views in common?

The KT boundary was formed over many thousands of years.

Large animals such as the dinosaurs died out gradually over millions of years.

Mass extinction occurred as an indirect result of debris saturating the atmosphere.

It is unlikely that the specific cause of the Cretaceous extinctions will ever be determined.

Volcanic activity may have been triggered by shock waves from the impact of an asteroid.

The author mentions “recent studies in North America” (lines 16–17) primarily in order to

point out the benefits of using field research to validate scientific theories.

suggest that the asteroid impact theory is not consistent with fossil evidence.

describe alternative methods of collecting and interpreting fossils.

summarize the evidence that led to wider acceptance of catastrophic scenarios of mass extinction.

show that dinosaurs survived until the end of the Cretaceous period.

Step 1: Read the Passage Strategically

Here’s an example of how the passage should be analyzed. We’ve reprinted the passage as seen through the lens of strategic reading. On the left is the passage as you might read it, with keywords and important points in bold. On the right is what you might be thinking as you read.

PASSAGE |

Analysis |

… the notion that mass extinctions at the end of the Cretaceous period 65 million years ago resulted from a sudden event has slowly gathered support, although even today there is no scientific consensus. In the Alvarez scenario, [bunch of details about an asteroid] |

The first sentence is rich with information for the strategic reader. Not only do you get the topic (mass extinctions at the end of the Cretaceous period—whatever that is), but you also get an idea (the notion that [the mass extinction] resulted from a sudden event), the fact that some people agree with it (slowly gathered support), and the fact that not everyone does (no scientific consensus). You can predict that the passage will go on to talk not only about the support but also about why not everyone agrees. You also get one specific theory (the Alvarez scenario) and an elaborate description of what that is—it seems to involve an asteroid. |

Alvarez’s main evidence is [lots of detail] |

The keywords are pretty clear—here’s some evidence in support of one “sudden event” theory. You don’t need to focus too much on what the evidence is until there’s a question about it. |

Paleontologists initially dismissed the theory, arguing that [something] last[ed] millions of years. But recent studies … doubts about theories of mass extinction have lessened significantly. |

With dismissed the theory, it’s clear that this paragraph shows why some would oppose the “sudden event” idea (just as you predicted). Note that millions of years, not normally a keyword, creates contrast with “sudden event.” Then the keyword But announces a change in direction: the recent studies lend support for the “sudden event” theory, so doubts have lessened significantly. |

Given the lack of [evidence] to fit the Alvarez scenario, some scientists have proposed alternatives. Courtillot, citing [evidence], speculates that eruptions … cause[d] global devastation. His analyses also conclude [something about iridium]. Alvarez and Asaro reply … But evidence … remains inconclusive. |

Alvarez lacks some evidence still, so there are some other theories. Courtillot says something about volcanoes and iridium. It looks like Alvarez makes a counterargument to Courtillot, too. But there isn’t enough evidence either way, so the author doesn’t pick a “winner.” |

Your Passage Map would look something like this:

This isn’t the only way to word the Passage Map, of course. Anything along these lines would work—so long as you note that there are two theories and that the author doesn’t ultimately prefer one to the other.

Step 2: Analyze the Question Stem

Now it’s time to move to the questions and identify the question type. Question 1 is what you will learn to call an Inference question: it uses the phrase can be inferred. Luckily, this Inference question contains clues that point you to a specific part of the passage. This will save you a lot of time. Question 2 is a Logic question. The phrase in order to indicates that you’re asked to identify why the author includes this detail.

Step 3: Research the Relevant Text

Question 1 asks you to find something that must be true according to both the Alvarez and the Courtillot theories. Our Passage Map shows that the Alvarez theory takes all of paragraph 2 and some of paragraph 4. That’s too much to reread closely. But the Courtillot theory is mentioned only once, in paragraph 4 lines 22–26. Probably the most efficient way to research this question is to read through those two sentences and then deal with paragraph 2, doing focused research on each answer choice as needed.

Question 2 refers to lines 16–17, which are in paragraph 3. Since this is a Logic question, it’s best to begin your research with the Passage Map. Here’s what the Map has to say about paragraph 3:

¶3: Initial disagreement, recent studies, now less doubt

So the “recent studies in North America” are either part of the initial disagreement or a reason that theories of mass extinction are less doubted now. Already, the word recent suggests the latter. But if you weren’t confident about that, you could read the context of lines 16–17. The keywords initially dismissed the theory [of mass extinction] from the sentence before and from the sentence after (Since these discoveries, doubts about theories of mass extinctions have lessened significantly.) seal the deal.

Step 4: Make a Prediction

The answer to Question 1, as you know, must be consistent with both theories. Since you researched Courtillot’s theory, you can quickly eliminate any answer choice that disagrees with it.

Question 2 asks why the “recent studies in North America” were mentioned. Your research shows you that they provide the evidence that reduces doubt about theories of mass extinction. So an easy prediction would be something like “reasons why theories of mass extinction are doubted less than they used to be.”

Step 5: Evaluate the Answer Choices

Question 1—(A) says that the KT boundary was formed over thousands of years, and that’s consistent with Courtillot (line 26). What about Alvarez? Scanning through paragraph 2 for anything about “KT boundary” and time, you read in lines 9–11: “KT boundary … rapid, massive deposition.” The word rapid is the only time signal at all, and it hardly fits with many thousands of years. Eliminate (A). Perhaps you could eliminate (B) right away if you remembered that both theories are in the “sudden event” camp. But if not, your Passage Map saves the day—dinosaurs died out gradually over millions of years fits with dinosaur records showed a decline lasting millions of years in paragraph 3. But your Map shows that to be evidence against Alvarez, not in support. So (B) is gone.

Debris saturating the atmosphere is consistent with Courtillot (line 24). What about Alvarez? Line 9 says slow fall of interplanetary debris. So both theories involve debris. Does it saturate the atmosphere? Not explicitly. But this is an Inference question, and you shouldn’t expect to see things repeated explicitly from the passage. You do see that there was a massive deposition … and massive would suggest that there’s a lot of this debris, so it’s plausible that it saturated the atmosphere. There’s not enough evidence to rule out (C), so you can leave it alone for now.

(D) is the opposite of what Courtillot (as well as Alvarez) is trying to do, so this is a quick big-picture elimination. (E) is consistent with Alvarez’s reply (lines 26–28). But this is a reply to Courtillot’s theory—not his theory itself. The passage gives no indication of whether Courtillot would agree with this claim, so (E) is eliminated. Only (C) is left standing, so it must be right.

Note that you can prove (C) to be the right answer without proving why it’s right. To prove why (C) is correct, you’d not only have to connect all the dots in paragraph 2, you’d have to tie it all to mass extinctions by going back to details from paragraph 1. It’s much more efficient to eliminate (A), (B), (D), and (E).

Question 2—Your predicted answer from Step 4 (“reasons why theories of mass extinction are doubted less than they used to be”) leads directly to (D), the correct answer.

(A) sounds nice on its own, but the context has nothing to do with the benefits of field research in a specific way. (B) is the opposite of why those studies are introduced—it is in fact the old belief that these studies dispel. (C) and (E) focus on the details in lines 16–17 themselves—(C) in a distorted way—but not on why those details are there.

READING COMPREHENSION QUESTION TYPES

Though you might be inclined to classify Reading Comp according to the kinds of passages that appear—business, social science, biological science, or physical science—it’s more effective to do so by question type. While passages differ in their content, you can read them in essentially the same way, employing the same strategic reading techniques for each.

Now that you’re familiar with the basic principles of Critical Reasoning and the Kaplan Method, let’s look at the most common types of questions. Certain question types appear again and again on the GMAT, so it pays to understand them beforehand.

The four main question types on GMAT Reading Comp are Global, Detail, Inference, and Logic. Let’s walk through each of these question types in turn, focusing on what they ask and how you can approach them most effectively.

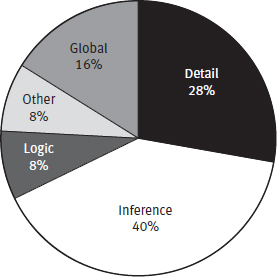

The Approximate Distribution of GMAT Reading Comprehension Questions

Global Questions

Any question that explicitly asks you to consider the passage as a whole is a Global question. Here are some examples:

Which of the following best expresses the main idea of the passage?

The author’s primary purpose is to …

Which of the following best describes the organization of the passage?

Which of the following would be an appropriate title for this passage?

The correct answer will be consistent with the passage’s topic, scope, purpose, and structure. If you’ve jotted these down on your noteboard (and you should!), then it will only take a few seconds to select the right answer.

The GMAT will probably word the answer choices rather formally, so by “few seconds,” we mean closer to 45 than to 10. But that’s still significantly under your average time per question, meaning that you can spend more time dealing with the trickier Inference questions.

Most wrong answers will either get the scope wrong (too narrow or too broad) or misrepresent the author’s point of view. Be wary of Global answer choices that are based on details from the first or last paragraph. These are usually traps laid for those who wrongly assume that GMAT passages are traditional essays with “topic sentences” and “concluding sentences.”

Often answer choices to Global questions asking about the author’s purpose will begin with verbs; in this case, the most efficient approach is to scan vertically to eliminate choices with verbs that are inconsistent with the author’s purpose. Common wrong answers misrepresent a neutral author by using verbs that indicate an opinionated stance.

TAKEAWAYS: GLOBAL QUESTIONS

Step 1 of the Kaplan Method provides you with the information you need to predict the answer to Global questions.

Use your Passage Map, topic, scope, and purpose to predict an answer. Then search the answer choices.

If you can’t find your prediction among the answer choices, eliminate wrong answer choices that misrepresent the scope.

When all of the answer choices start with a verb, try a vertical scan, looking for choices that match your prediction or looking to eliminate choices that misrepresent the author’s purpose.

Detail Questions

Detail questions ask you to identify what the passage explicitly says. Here are some sample Detail question stems:

According to the passage, which of the following is true of X?

The author states that …

The author mentions which of the following in support of X?

It would be impossible to keep track of all of the details in a passage as you read through it the first time. Fortunately, Detail stems will always give you clues about where to look to find the information you need. Many Detail stems include specific words or phrases that you can easily locate in the passage. A Detail stem might even highlight a sentence or phrase in the passage itself. Using these clues, you can selectively reread parts of the passage to quickly zero in on the answer—a more efficient approach than memorization.

So between highlighting, references to specific words or phrases, and your Passage Map, locating the detail that the GMAT is asking about is usually not much of a challenge. What, then, could these questions possibly be testing? They are testing whether you understand that detail in the context of the passage. The best strategic approach, then, is to read not only the sentence that the question stem sends you to but also the sentences before and after it. Consider the following question stem:

According to the passage, which of the following is true of the guinea pigs discussed in the highlighted portion of the passage?

Let’s say that the highlighted portion of the passage goes like this:

… a greater percentage of the guinea pigs that lived in the crowded, indoor, heated area survived than did the guinea pigs in the outdoor cages.

If you don’t read for context, you might think that something like this could be the right answer choice:

Guinea pigs survive better indoors.

But what if you read the full context, starting one sentence before?

Until recently, scientists had no evidence to support the hypothesis that low temperature alone, and not other factors such as people crowding indoors, is responsible for the greater incidence and severity of influenza in the late fall and early winter. Last year, however, researchers uncovered several experiment logs from a research facility whose population of guinea pigs suffered an influenza outbreak in the winter of 1945; these logs documented that a greater percentage of the guinea pigs that lived in the indoor, heated area survived than did the guinea pigs in the outdoor cages.

Now you could identify this as the right answer:

Researchers discovered that some guinea pigs survived better indoors than outdoors during a flu outbreak.

By reading not just the highlighted portion of the passage but the information before it, you realize that it’s not necessarily true that guinea pigs always survive better indoors; only a specific subset did. If you had picked an answer that matched the first prediction, you would be distorting the facts—you need to understand the information in context.

Make sure that you read entire sentences when answering Detail questions. Notice here that the question stem sends you to the end of the last sentence, but it’s the “no evidence” and “however” at the beginning of the sentences that form the support for the right answer.

TAKEAWAYS: DETAIL QUESTIONS

On Detail questions, use your Passage Map to locate the relevant text in the passage. If necessary, read that portion of the passage again. Then predict an answer.

On Detail questions, never pick an answer choice just because it sounds familiar. Wrong answer choices on Detail questions are often distortions of actual details in the passage.

All of the information needed to answer Detail questions is in the passage.

Inference Questions

Reading Comp Inference questions, like Critical Reasoning Inference questions, ask you to find something that must be true based on the passage but is not mentioned explicitly in the passage. In other words, you need to read “between the lines.” Here are some sample Inference question stems:

Which of the following is suggested about X?

Which of the following can be most reasonably inferred from the passage?

The author would most likely agree that …

Inference questions come in two types. The first uses key phrases or highlighting to refer to a specific part of the passage. To solve this kind of question, find the relevant detail in the passage and consider it in the context of the material surrounding it. Then make a flexible prediction about what the correct answer will state.

Consider the following Inference question, once again asking about the guinea pigs we discussed earlier:

Which of the following is implied about the guinea pigs mentioned in the highlighted portion of the passage?

Just like last time, you want to review the context around the highlighted portion. Doing so, you’ll find that “until recently,” there was “no evidence” that temperature affected the flu; “however,” last year these guinea pig records appeared. The logical inference is not explicitly stated, but you can easily put the information from the two sentences together. The answer will be something like this:

Their deaths provided new evidence that influenza may be more dangerous in lower temperatures.

Other Inference questions make no specific references, instead asking what can be inferred from the passage as a whole or what opinion the author might hold. Valid inferences can be drawn from anything in the passage, from big-picture issues like the author’s opinion to any of the little details. But you will probably be able to eliminate a few answers quickly because they contradict the big picture.

Then you’ll investigate the remaining answers choice by choice, looking to put each answer in one of three categories—(1) proved right, (2) proved wrong, or (3) not proved right but not proved wrong either. It’s distinguishing between the second and third categories that will lead to success on Inference questions. Don’t throw away an answer because you aren’t sure about it or “don’t like it.”

If you can’t find material in the passage that proves an answer choice wrong, don’t eliminate it. Since the correct answer to an Inference question is something that must be true based on the passage, you can often find your way to the correct answer by eliminating the four choices that could be false.

TAKEAWAYS: INFERENCE QUESTIONS

On Inference questions, search for the answer choice that follows from the passage.

When it’s difficult to predict a specific answer to an Inference question, you still know that “the right answer must be true based on the passage.”

Wrong answer choices on Inference questions often use extreme language, or they exaggerate views expressed in the passage.

Logic Questions

Logic questions ask why the author does something—why he cites a source, why he includes a certain detail, why he puts one paragraph before another, and so forth. Another way of thinking of Logic questions is that they ask not for the purpose of the passage as a whole but for the purpose of a part of the passage. As a result, any answer choice that focuses on the actual content of a detail will be wrong.

Here are some sample Logic question stems:

The author mentions X most probably in order to …

Which of the following best describes the relationship of the second paragraph to the rest of the passage?

What is the primary purpose of the third paragraph?

Most Logic questions can be answered correctly from your Passage Map—your written summary of each paragraph and the passage’s overall topic, scope, and purpose. If the question references a detail, as does the first sample question stem above, then you should read the context in which that detail appears as well—just as you should for any Detail or Inference question that references a specific detail.

TAKEAWAYS: LOGIC QUESTIONS

On Logic questions, predict the correct answer using the author’s purpose and your Passage Map.

Answer choices that focus too heavily on specifics are usually wrong—it’s not content that’s key in Logic questions but the author’s motivation for including the content.

“Other” Questions

As you saw from the pie chart earlier, approximately 8 percent of Reading Comp questions will not fall neatly into the four main categories described above. On such questions, strategic reading of the question stem becomes even more important, since you’ll need to define precisely what the question is asking you to do, and you may not be able to identify any specific “pattern” that the question falls into. But even within these rare “Other” question types, you can prepare yourself to see questions of the following varieties.

“Critical Reasoning” Questions

Occasionally in Reading Comp, you might find a question that seems more like one of the common Critical Reasoning question types, such as an Assumption, Strengthen, Weaken, or Flaw question. These questions refer to arguments, just as they do in Critical Reasoning—although unlike in Critical Reasoning, a particular argument will usually be confined to just one paragraph or portion of the Reading Comp passage, rather than the entire passage focusing on a single argument.

When you see questions like this, you should research the portion of the passage that includes the argument referenced by the question stem. Just as you would in Critical Reasoning, identify the conclusion and relevant evidence; then use the central assumption to form a prediction for the right answer.

Parallelism Questions

These questions ask you to take the ideas in a passage and apply them through analogy to a new situation. For example, a passage might describe a chain of economic events that are related causally, such as reduced customer spending leading to a slowdown of industrial production, which in turn leads to the elimination of industrial jobs. A Parallelism question might then ask you the following:

Which of the following situations is most comparable to the economic scenario described the passage?

In this case, the correct answer will describe a scenario that is logically similar to the one in the passage. Don’t look for a choice that deals with the same subject matter as the passage, as such choices are often traps. Parallelism questions are more concerned with structure than substance, so the correct answer will provide a chain of causally connected events, such as water pollution from a factory causing the death of a certain type of algae, which in turn causes a decline in the fish population that relied on that type of algae as its primary food source.

Application Questions

Application questions ask you to identify an example or application of something described in the passage. For instance, if the passage describes a process for realigning a company’s management structure, an Application question could give you five answer choices, each of which describes the structure of a given company. Only the correct answer choice will accurately reflect the process described in the passage.

Application questions function similarly to Parallelism questions, except that whereas Parallelism questions ask you to identify an analogous logical situation (irrespective of subject matter), Application questions ask you to apply information or ideas directly, within the same subject area (rather than by analogy or metaphor).

Question Type Identification Exercise

Answers follow this exercise

Identifying the question type during Step 2 of the Kaplan Method for Reading Comprehension is a chance for you to put yourself in control of the entire process that follows: how to research, what to predict, and, thus, how to evaluate answer choices. Use the Core Competency of Pattern Recognition to analyze keywords in the question stem and determine what the question is asking you to do. Based on this analysis, choose the correct question type from the list of choices.

The passage implies which of the following about XXXXXXX?

Global

Detail

Inference

Logic

Other

According to the passage, each of the following is true of XXXXXXX EXCEPT

Global

Detail

Inference

Logic

Other

The author mentions XXXXXXX in order to

Global

Detail

Inference

Logic

Other

The author’s primary objective in the passage is to

Global

Detail

Inference

Logic

Other

The author makes which of the following statements concerning XXXXXXX?

Global

Detail

Inference

Logic

Other

An appropriate title for the passage would be

Global

Detail

Inference

Logic

Other

Which of the following statements about XXXXXXX can be inferred from the passage?

Global

Detail

Inference

Logic