CHAPTER 9

Quantitative Section Overview

Composition of the Quantitative Section

What the Quantitative Section Tests

Pacing on the Quantitative Section

How the Quantitative Section Is Scored

Core Competencies on the Quantitative Section

COMPOSITION OF THE QUANTITATIVE SECTION

Slightly fewer than half of the multiple-choice questions that count toward your overall score appear in the Quantitative (math) section. You’ll have 75 minutes to answer 37 Quantitative questions in two formats: Problem Solving and Data Sufficiency. These two types of questions are mingled throughout the Quantitative section, so you never know what’s coming next. Here’s what you can expect to see:

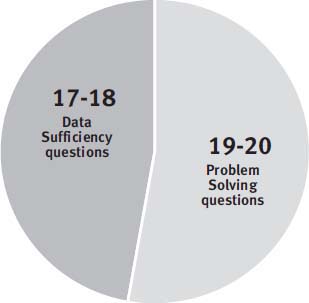

The Approximate Mix of Questions on the GMAT Quantitative Section:

19-20 Problem Solving Questions and 17–18 Data Sufficiency Questions

You may see more of one question type and fewer of the other. Don’t worry. It’s likely just a slight difference in the types of “experimental” questions you get.

WHAT THE QUANTITATIVE SECTION TESTS

Math Content Knowledge

Of course, the GMAT tests your math skills. So you will have to work with concepts that you may not have used for the last few years. Calculator use is not permitted on the Quantitative section, and even if you use math all the time, it’s probably been a while since you were unable to use a calculator or computer to perform computations. So refreshing your fundamental math skills is definitely a crucial part of your prep.

But the range of math topics tested is actually fairly limited. The GMAT covers only the math that U.S. students usually see during or before their first two years of high school. No trigonometry, no advanced algebra, no calculus. As you progress in your GMAT prep, you’ll see that the same concepts are tested again and again in remarkably similar ways.

Areas of math content tested on the GMAT include the following: algebra, arithmetic, number properties, proportions, basic statistics, certain specific math formulas, and geometry. Algebra and arithmetic are the most commonly tested topics—they are tested either directly or indirectly on a majority of GMAT Quantitative questions. Geometry questions account for fewer than one-sixth of all GMAT math questions, but they can often be among the most challenging for test takers, so you may benefit from thorough review and practice with these concepts.

A large part of what makes the GMAT Quantitative section so challenging, however, is not the math content itself, but rather how the testmakers combine the different areas of math to make questions more challenging. Rare is the question that tests a single concept; more commonly, you will be asked to integrate multiple skills to solve a question. For instance, a question that asks you about triangles could also require you to solve a formula algebraically and apply your understanding of ratios to find the correct answer.

Quantitative Analysis

Most of the math tests you’ve taken before—even other standardized tests like the SAT and the ACT—ask questions in a fairly straightforward way. You know pretty quickly how you should solve the problem, and the only thing holding you back is how quickly or accurately you can do the math.

But the GMAT is a little different. Often the most difficult part of a GMAT Quantitative problem is figuring out which math skills to use in the first place. In fact, the GMAT’s hardest Quantitative problems are about 95 percent analysis, 5 percent calculation. You’ll have to do the following:

Understand complicated or awkward phrasing.

Process information presented out of order.

Analyze incomplete information.

Simplify complicated information.

In the next few chapters, we’ll show you how to approach Quant problems strategically so you can do the analysis that will lead you to efficient solutions, correct answers, and a high score. But first, let’s look at some techniques for managing the Quantitative section as a whole.

PACING ON THE QUANTITATIVE SECTION

The best way to attack the computer-adaptive GMAT is to exploit the way it determines your score. Here’s what you’re dealing with:

Penalties: If you run out of time at the end of the section, you receive a penalty that’s about twice what you’d have received if you got all those answers wrong. And there’s an extra penalty for long strings of wrong answers at the end.

No review: There is no going back to check your work. You cannot move backward to double-check your earlier answers or skip past a question that’s puzzling and return to try it again later. So if you finish early, you won’t be able to use that remaining time.

Difficulty level adjustment: Questions get harder or easier, depending on your performance. Difficult questions raise your score more when you get them right and hurt your score less when you get them wrong. Easier questions are the opposite—getting them right helps your score less, and getting them wrong hurts your score more.

Obviously, the best of both worlds is being able to get the early questions mostly right, while taking less than two minutes per question on average so that you have a little extra time to think about those harder questions later on. To achieve that goal, you need to do three things:

Know your math basics cold. Don’t waste valuable time on Test Day sweating over how to add fractions, reverse-FOIL quadratic equations, or use the rate formula. When you do math, you want to feel right at home.

Look for strategic approaches. Most GMAT problems are susceptible to multiple possible approaches. So the testmakers deliberately build in shortcuts to reward critical thinkers by allowing them to move quickly through the question, leaving them with extra time. We’ll show you how to find these most efficient approaches.

Practice, practice, practice. Do lots of practice problems so that you get as familiar as possible with the GMAT’s most common analytical puzzles. That way you can handle them quickly (and correctly!) when you see them on Test Day. We’ve got tons in the upcoming chapters.

If you follow this advice, you’ll do more than just set yourself up to manage your pacing well. You’ll also ensure that most of the questions fall into a difficulty range that’s right for you. If you struggle on a few hard questions and are sent back down to the midrange questions, that’s OK! You’ll get them correct, which will send you right back up to the high-value hard questions again.

During the test, do your best not to fall behind early on. Don’t rush, but don’t linger. Those first 5 questions shouldn’t take more than 10 minutes total, and the first 10 questions shouldn’t take more than 20 minutes. Pay attention to your timing as you move through the section. If you notice that you are falling behind, try to solve some questions more quickly (or if you’re stuck, make strategic guesses) to catch up.

Strategic Guessing

Since missing hard questions doesn’t hurt your score very much but not finishing definitely does, making a few guesses on the hardest questions will give you the chance to finish on time and earn your highest possible score.

Occasionally, you’ll find that you have to make a guess, but don’t guess at random. Narrowing down the answer choices first is imperative. Otherwise, your odds of getting the right answer will be pretty slim. Follow this plan when you guess:

Eliminate answer choices you know are wrong. You can often identify wrong answer choices after a little calculation. For instance, on Data Sufficiency questions, you can eliminate at least two answer choices by determining the sufficiency of just one statement.

Avoid answer choices that make you suspicious. You can get rid of these without doing any work on the problem! These answer choices either don’t make logical sense with the problem, or they conform to common wrong-answer types. For example, if only one of the answer choices in a Problem Solving question is negative, chances are that it will be incorrect.

Choose one of the remaining answer choices. The fewer options you have to choose from, the higher your chances of selecting the right answer. You can often identify the correct answer using estimation, especially if the answer choices are spaced widely apart.

Experimental Questions

Some questions on the GMAT are experimental. These questions are not factored into your score. They are questions that the testmaker is evaluating for possible use on future tests. To get good data, the testmakers have to test each question against the whole range of test takers—that is, high and low scorers. Therefore, you could be on your way to an 800 and suddenly come across a question that feels out of line with how you think you are doing.

Don’t panic; just do your best and keep on going. The difficulty level of the experimental questions you see has little to do with how you’re currently scoring. Remember, there is no way for you to know for sure whether a question is experimental or not, so approach every question as if it were scored.

Keep in mind that it’s hard to judge the true difficulty level of a question. A question that seems easy to you may simply be playing to your personal strengths and be very difficult for other test takers. So treat every question as if it counts. Don’t waste time trying to speculate about the difficulty of the questions you’re seeing and what that implies about your performance. Rather, focus your energy on answering the question in front of you as efficiently as possible.

HOW THE QUANTITATIVE SECTION IS SCORED

The Quantitative section of the GMAT is quite different from the math sections of paper-and-pencil tests you may have taken. The major difference between the test formats is that the GMAT computer-adaptive test (CAT) adapts to your performance. Each test taker is given a different mix of questions, depending on how well he or she is doing on the test. In other words, the questions get harder or easier depending on whether you answer them correctly or incorrectly. Your GMAT score is not determined by the number of questions you get right but rather by the difficulty level of the questions you get right.

When you begin a section, the computer

assumes you have an average score (500), and

gives you a medium-difficulty question. About half the people who take the test will get this question right, and half will get it wrong. What happens next depends on whether you answer the question correctly.

If you answer the question correctly,

your score goes up, and

you are given a slightly harder question.

If you answer the question incorrectly,

your score goes down, and

you are given a slightly easier question.

This pattern continues for the rest of the section. As you get questions right, the computer raises your score and gives you harder questions. As you get questions wrong, the computer lowers your score and gives you easier questions. In this way, the computer homes in on your score.

If you feel like you’re struggling at the end of the section, don’t worry! Because the CAT adapts to find the outer edge of your abilities, the test will feel hard; it’s designed to be difficult for everyone, even the highest scorers.

CORE COMPETENCIES ON THE QUANTITATIVE SECTION

Unlike most subject-specific tests you have taken throughout your academic career, the scope of knowledge that the GMAT requires of you is fairly limited. In fact, you don’t need any background knowledge or expertise beyond fundamental math and verbal skills. While mastering those fundamentals is essential to your success on the GMAT—and this book is concerned in part with helping you develop or refresh those skills—the GMAT does not primarily seek to reward test takers for content-specific knowledge. Rather, the GMAT is a test of high-level thinking and reasoning abilities; it uses math and verbal subject matter as a platform to build questions that test your critical thinking and problem solving capabilities. As you prepare for the GMAT, you will notice that similar analytical skills come into play across the various question types and sections of the test.

Kaplan has adopted the term “Core Competencies” to refer to the four bedrock thinking skills rewarded by the GMAT: Critical Thinking, Pattern Recognition, Paraphrasing, and Attention to the Right Detail. The Kaplan Methods and strategies presented throughout this book will help you demonstrate these all-important skills. Let’s dig into each of the Core Competencies in turn and discuss how each applies to the Quantitative section.

Critical Thinking

Most potential MBA students are adept at creative problem solving, and the GMAT offers many opportunities to demonstrate this skill. You probably already have experience assessing situations to see when data are inadequate; synthesizing information into valid deductions; finding creative solutions to complex problems; and avoiding unnecessary, redundant labor.

In GMAT terms, a critical thinker is a creative problem solver who engages in critical inquiry. One of the traits of successful test takers is their skill at asking the right questions. GMAT critical thinkers first consider what they’re being asked to do, then study the given information and ask the right questions, especially, “How can I get the answer in the most direct way?” and “How can I use the question format to my advantage?”

For instance, the answer choices in a GMAT Problem Solving question often give clues to the solution. Use them. As you examine a Problem Solving question, you’ll ask the testmaker: “What are you really looking for in this math problem?” or “Why have you set things up in this way?” You might even discover opportunities to find the answer to a difficult question by plugging the answer choices into the information in the question—a strategy Kaplan calls “Backsolving.”

Likewise, as you examine a Data Sufficiency question, you’ll learn to ask: “What information will I need to answer this question?” or “How can I determine whether more than one solution is possible?”

Those test takers who learn to ask the right questions become creative problem solvers—and GMAT champs. Let’s see how to apply the GMAT Core Competency of Critical Thinking to a sample Problem Solving question:

If the perimeter of a rectangular property is 46 meters, and the area of the property is 76 square meters, what is the length of each of the shorter sides?

4

6

9

18

23

This question is a perfect example of one that can be answered with minimal calculations, provided the test taker understands how to use the test format to his advantage.

Here you are asked for the shorter sides of a rectangle. Recalling the formula for the area of a rectangle (area = length × width) may help you see a shorter path to the solution here. Rather than set up a complicated system of equations, remember that the property is 76 square meters in size. Since you’re looking for the shorter side, you’re looking for the smaller number that, when multiplied by a larger number, yields 76. You can immediately eliminate 9, 18, and 23 as possible answers, since multiplying any of those numbers by something larger than itself will give a result bigger than 76. Out of the two remaining choices, 4 divides evenly into 76. If the shorter sides measure 4, the larger sides would measure 19. And if the dimensions of the rectangle are 4 and 19, then the perimeter does equal 46. Therefore, choice (A) is correct.

This isn’t to say that all questions are amenable to such amazing “shortcuts.” But it is true that almost every question on the Quantitative section of the GMAT could be solved using more than one approach. The time constraints on the GMAT are designed to reward those test takers who, through Critical Thinking and practice, have honed their ability to identify and execute the most efficient approach to every problem they might see on Test Day.

Pattern Recognition

Most people fail to appreciate the level of constraint that standardization places on testmakers. Because the testmakers must give reliable, valid, and comparable scores to many thousands of students each year, they’re forced to reward the same skills on every test. They do so by repeating the same kinds of questions with the same traps and pitfalls, which are susceptible to the same strategic solutions.

Inexperienced test takers treat every problem as if it were a brand-new task, whereas the GMAT rewards those who spot the patterns and use them to their advantage. Of course Pattern Recognition is a key business skill in its own right: executives who recognize familiar situations and apply proven solutions to them will outperform those who reinvent the wheel every time.

Even the smartest test taker will struggle if she approaches each GMAT question as a novel exercise. But the GMAT features nothing novel—just repeated patterns. Kaplan knows this test inside and out, and we’ll show you which patterns you will encounter on Test Day. You will know the test better than your competition does. Let’s see how to apply the GMAT Core Competency of Pattern Recognition to a sample Problem Solving question:

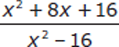

If x > 7, which of the following is equal to

?

?

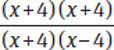

This question features one of the many patterns that is repeated over and over in the Quantitative section. The Kaplan-trained test taker looks at this problem and sees two “classic quadratics”: the square of a binomial in the numerator and the difference of squares in the denominator. Factoring these expressions allows you to rewrite them as follows:

You can then cancel an (x + 4) on the top and bottom and choose the correct answer, choice (D). As you practice with more and more GMAT questions, stay attuned to patterns you see; certain math concepts appear regularly enough on the GMAT to warrant memorization.

Paraphrasing

The third Core Competency is Paraphrasing: the GMAT rewards those who can reduce difficult, abstract, or polysyllabic prose to simple terms. Paraphrasing is, of course, an essential business skill: executives must be able to define clear tasks based on complicated requirements and accurately summarize mountains of detail.

In the Quantitative section of the GMAT, you will often be asked to paraphrase English as “math” or to simplify complicated equations using arithmetic or algebraic properties. Let’s see how to apply the GMAT Core Competency of Paraphrasing to a sample Problem Solving question:

A basketball team plays games only against the other five teams in its league and always in the following order: Croton, Darby, Englewood, Fiennes, and Garvin. If the team’s final game of the season is against Fiennes, which of the following could be the number of games in the team’s schedule?

18

24

56

72

81

Rather than become intimidated by the complicated wording of this question, a smart test taker will ask, “How might I rephrase this question more simply?” A good paraphrase looks something like this: a team plays five other teams over and over in the same order, but the season stops at Fiennes. This is the fourth game of the sequence; what could the total number of games be?

With this paraphrase in hand, it’s time to employ some Critical Thinking. Suppose the team plays a full round, and the next round is interrupted after the fourth game—what will the total number of games be? 5 + 4 = 9. Suppose there are two full rounds before the interruption? 5 + 5 + 4 = 14. Three rounds? 5 + 5 + 5 + 4 = 19. Thinking through these scenarios causes the pattern to emerge: the answer must end in 4 or 9. The correct choice is (B), which represents four full rounds plus a set of four games ending with Fiennes.

Notice how this convoluted word problem becomes manageable once paraphrased. Putting GMAT prose into your own words helps you get a handle on the situation being described and know what to do next.

Attention to the Right Detail

Details present a dilemma: missing them can cost you points. But if you try to absorb every fact in a complicated word problem all at once, you may find yourself swamped, delayed, and still unable to determine the best approach, because you haven’t sorted through the information to determine what’s most important. Throughout this book, you will learn how to discern the essential details from those that can slow you down or confuse you. The GMAT testmakers reward examinees for paying attention to “the right details”—the ones that make the difference between right and wrong answers.

Attention to the Right Detail distinguishes great administrators from poor ones in the business world as well. Just ask anyone who’s had a boss who had the wrong priorities or who was so bogged down in minutiae that the department stopped functioning.

Not all details are created equal, and there are mountains of them on the test. Learn to target only what will turn into correct answers. Let’s see how to apply the GMAT Core Competency of Attention to the Right Detail to a sample Problem Solving question:

A drought decreased the amount of water in city X’s reservoirs from 118 million gallons to 96 million gallons. If the reservoirs were at 79 percent of total capacity before the drought began, approximately how many million gallons were the reservoirs below total capacity after the drought?

67

58

54

46

32

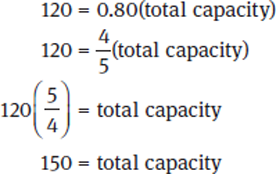

There are a lot of words in this problem, but there’s one that’s more important than all the others. Recognizing the word “approximately” is crucial to being able to take a strategic approach to this question.

Attention to the Right Detail on the Quantitative section also means defining precisely what the question is asking you to solve for. Here you need the current (post-drought) difference between capacity and holdings. Identifying up front what you need to solve for is important on the GMAT because the answer choices will often include options that represent “the right answer to the wrong question”: the value you might come up with if you did all the math correctly but solved accidentally for a different unknown in the problem (for instance, the number of gallons below capacity the reservoir was before the drought).

This question gives information on the pre- and post-drought holdings, as well as on the pre-drought percentage of capacity. Use that info to approximate the current shortage. To start, figure out the total capacity before the drought. You know that 118 million was 79 percent of capacity. Because approximation is perfectly fine in this case, you can round these numbers to 120 million and 80 percent, respectively, to make the math easier. Then use the percent formula:

The question states that the current volume is 96 million gallons, which is 54 million gallons under capacity. Choice (C) is correct.

Think of how much time you saved by noticing that the question asked for an approximate value, thereby allowing you to avoid precise calculation with unwieldy numbers. Moreover, Attention to the Right Detail ensured that you did not select a trap answer choice: if you had accidentally solved for the total capacity and then subtracted 118 (the amount of water originally in the reservoir), you would have selected incorrect choice (E).