How Natural Selection Creates Social Instincts

CHARLES DARWIN, IN The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1873), was the first to advance the idea that instinct evolves by natural selection. Simple in style and profusely illustrated, this last and least known of his four great books argued that the behavioral traits defining each species, no less than those defining traits of their anatomy and physiology, are hereditary. They arose and exist today, Darwin said, because in the past they aided survival and reproduction.

Darwin’s fundamental insight has been verified over and again. It underpins much of what we understand about behavior today. Its potency is the reason that a century later Konrad Lorenz, one of the founders of modern animal behavior research, called Darwin the patron saint of psychology.

Yet—no idea of modern science stirred more controversy than that of human instinct as a product of mutation and natural selection. In the 1950s it survived the onslaught of radical behaviorism of the kind masterminded by B. F. Skinner, the idea that all behavior in both animals and humans is somehow and at some stage or other of each individual’s development the product of learning. In the two decades that followed, the idea of instinct shaped by natural selection defeated this perception of the brain as a blank slate. At least it did so for animals. For two more decades, however, the blank slate was kept alive for human social behavior. Many writers in the social sciences and humanities continued to insist that the mind is entirely the product of its environment and past history. Free will exists and is powerful, they said. The mind is ultimately at the command of will and fate. What evolves in the mind, they finally argued, is exclusively cultural; there is no such thing as a genetically based human nature.

In fact, the evidence for instinct and human nature was already compelling at that time. Today it is overwhelming in amount and rigor, with new evidence added whenever it is tested. Instinct and human nature are increasingly the subject of studies in genetics, neuroscience, anthropology, and, nowadays, even in the social sciences and humanities themselves.

How does instinct evolve by natural selection? To keep the matter as elementary as possible, consider an imaginary population of birds nesting in a forest of mixed oak and pine. The birds choose only oak trees for their abode, a hereditary predisposition prescribed in the simplest possible way by one allele, in other words one form of two or more versions of one particular gene. Let us refer to the allele as a. Because of the influence of allele a, birds are automatically drawn to oak trees when they nest, preferring them over the numerous pine trees growing in the same forest. Their brains automatically select certain features that define oak trees. The features might be the height and contour of the canopy, for example, or the look and feel of the upper branches.

In one particular forest, an environmental shift occurs. Oak trees grow scarce because of local climate change and the inroads of a new disease. Pines, better adapted to the new conditions, begin to fill in the empty spaces. In time pines become dominant in the forest. Meanwhile, a second form of the same gene, the allele b, appears in the birds as a mutation of the oak-prone allele a. Perhaps b is not really a new mutation. Perhaps it has always been present at very low frequencies, sustained by mutations that have occurred rarely but repeatedly in the past. Or else pine-favoring b was carried in by an immigrant bird that strayed into the forest from another, mostly pine-loving population living in a nearby forest.

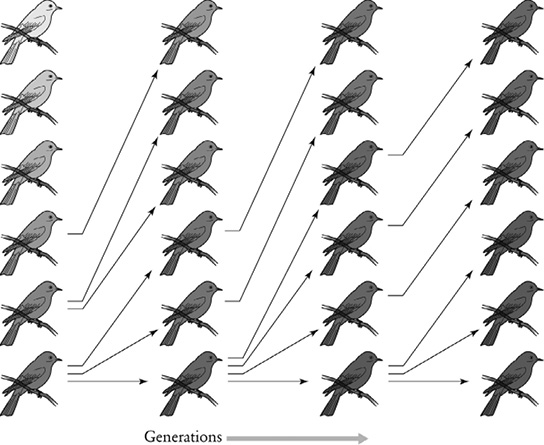

FIGURE 17-1. Evolution by genes in its simplest form occurs when two forms (alleles) of the same gene produce different traits—in this hypothetical example, color—because of the greater survival or reproduction or both of one of the forms (dark blue). (From Carl Zimmer, The Tangled Bank: An Introduction to Evolution [Greenwood Village, CO: Roberts, 2010], p. 33.)

Whatever its origin, this second allele, b, causes the birds carrying it to prefer nesting in pine trees instead of oak trees. In the changing forest, where pine is rising to dominance over oak, b now does better than a or, to be a bit more precise and to the point, birds carrying b do better than those carrying a. From one generation to the next, b increases in frequency within the bird population as a whole. It may eventually replace a entirely, or not. But in either case, evolution has occurred. This change in the heredity of the bird population is not large compared with the rest of the birds’ entire genetic code. It is an incident of “microevolution.” But its consequences are great. The shift from a preponderance of allele a to a preponderance of allele b allows the bird species to continue occupying a forest now covered mostly by pine. The evolutionary change has occurred by natural selection. The changing natural environment has selected allele b over the previously dominant a. One outcome of the habitat-selection instinct has been replaced by another.

In all populations of every species, such mutations are constantly occurring in all of the traits of the species, including behavior. They may be random changes in the base pairs, the “letters” of the DNA such as the change from allele a to allele b; or a building of small portions of the DNA molecule through duplication in sequences; or changes in the number or configuration of the chromosomes that carry the DNA molecules. Most mutations harm the organism in some way or another, and as a result they soon disappear—or at best they are kept at extremely low, “mutational” levels. But a very few, like the imaginary mutant allele b that opened the pine forest to the previously oak-specialist birds, do provide an advantage in survival or reproductive ability, or both. As a result, they increase in frequency in the population. Additional mutations, mostly bad but a very few good, continuously appear here and there throughout the genetic code. Consequently, evolution is always occurring.

Although mutant alleles and other genetic novelties occur commonly over the billions of DNA letters in the vast hereditary code of billions of letters, those composing any particular gene experience such an event very rarely. One in a million or one in ten million individuals per gene each generation are typical figures. Yet if any change does occur that is favorable to survival and reproduction, as in the imagined mutation to pine-prone allele b, it can spread rapidly. For example, it can increase from 10 percent to 90 percent of any of the alleles in the population in as few as ten generations—even when the advantage it confers is only slight.

A vast scientific literature now exists on the dynamics of evolution, based on a century of mathematical theory coupled with empirical studies in the field and laboratory. Present-day evolutionary biology, building upon this knowledge, is growing in compass, sophistication, and power. Researchers are advancing along a wide frontier of phenomena, including sexual and asexual reproduction and the molecular foundations of particulate heredity. Scientists are also working out the interactions of multiple genes during development of the cell and organism, together with the impact of different kinds of environmental pressures on microevolution.

Taken to fine detail, the subject of evolution at the level of the gene can become forbiddingly technical. Nevertheless, several overarching principles can be gleaned that are both easily grasped and crucial for understanding the genetic basis of instinct and social behavior.

One of the principles is the distinction between the unit of heredity, as opposed to the target of selection in the process that drives evolution. The unit is a gene or arrangement of genes that form part of the hereditary code (thus, a and b in the forest birds). The target of selection is the trait or combination of traits encoded by the units of heredity and favored or disfavored by the environment. Examples of targets are propensity for hypertension and resistance to a disease in humans, or, in the case of bird behavior, the instinctive choice of nest site.

Natural selection is usually multilevel: it acts on genes that prescribe targets at more than one level of biological organization, such as cell and organism, or organism and colony. An extreme example of multilevel selection exists in cancer. The cancerous cell is a mutant able to grow and multiply out of control at the expense of the organism, which is the community of cells forming the next higher level of biological organization. Selection occurring at one level, the cell, can work in the opposite direction from that of the adjacent level, the organism. The runaway cancer cells cause the larger community of cells (the organism) of which it is a member, to sicken and die. Conversely, the community stays healthy when the growth of the cancer cells is controlled.

In colonies composed of authentically cooperating individuals, as in human societies, and not just robotic extensions of the mother’s genome, as in eusocial insects, selection among genetically diverse individual members promotes selfish behavior. On the other hand, selection between groups of humans typically promotes altruism among members of the colony. Cheaters may win within the colony, variously acquiring a larger share of resources, avoiding dangerous tasks, or breaking rules; but colonies of cheaters lose to colonies of cooperators. How tightly organized and regulated a colony is depends on the number of cooperators as opposed to cheaters, which in turn depends on both the history of the species and the relative intensities of individual selection versus group selection that have occurred.

Traits (targets) that are acted upon exclusively by selection between groups are those emerging from interactions among members of each group. These interactions include communication, division of labor, dominance, and cooperation in performing communal tasks. If the quality of these interactions favors the colony using them over colonies using other or lesser interactions, the genes prescribing their performances will spread through the population of colonies with the passing of each generation of colonies.

Individual-versus-group selection results in a mix of altruism and selfishness, of virtue and sin, among the members of a society. If one colony member devotes its life to service over marriage, the individual is of benefit to the society, even though it does not have personal offspring. A soldier going into battle will benefit his country, but he runs a higher risk of death than one who does not. An altruist benefits the group, but a layabout or coward who saves his own energy and reduces his bodily risk passes the resulting social cost to others.

A second biological phenomenon essential to understanding the evolution of advanced social behavior is phenotypic plasticity. Consider a phenotype, defined as some trait of an organism prescribed at least in part by its genes. To return to the earlier imaginary example, the phenotype is the tendency of a bird to nest in either oak trees or pine trees. Next consider its genotype, the genes that prescribe the tendency to choose oak or pine trees, in this case the aforementioned alleles a or b. A phenotype prescribed by a particular genotype can be rigid in expression, such as five fingers on the hand or the color of an eye. Alternatively, it can be flexible, with its precise expression dependent in a predictable manner on the environment in which an individual develops. The b allele may prescribe a tendency to choose pine trees, but under a few conditions—perhaps rare—it chooses oak trees instead.

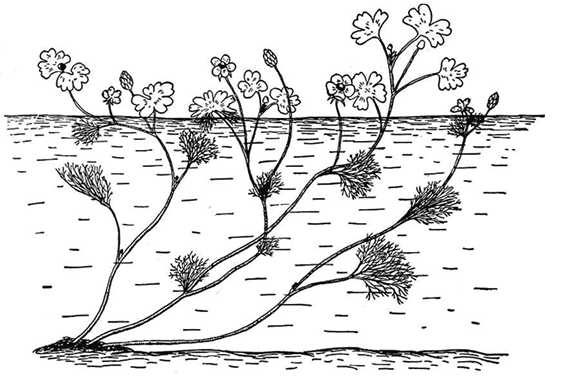

FIGURE 17-2. The water crowfoot (Ranunculus aquaticus) has extreme phenotype plasticity, with leaf form determined by the location of the leaf. (From Theodosius Dobzhansky, Evolution, Genetics, and Man [New York: Wiley, 1955].)

What is not widely appreciated, even among some biologists, is that the degree to which the amount of phenotype plasticity itself is subject to natural selection. In a classic example, the same genotype of the water crowfoot can grow one or the other of two types of leaves depending on which plant (or part of the plant) grows: broad, lobed leaves above the surface of the water, and brush-shaped leaves if under water. Both types can be produced by the same plant. And if a leaf emerges right at the water surface, the part above is broad and the part below is brush-shaped.

Finally, when thinking about evolution by natural selection, a crucial and necessary distinction to make is between proximate causation, which is how a structure or process works, and ultimate causation, which is why the structure or process exists in the first place. Consider the imaginary forest birds as they switch from oak trees to pine trees as the place to build their nests. The proximate cause of their evolution is the possession of the b allele that predisposes them to choose pine over oak. More precisely, the b allele prescribes the development of the endocrine and nervous systems that mediate their change in nesting behavior from oak to pine. The ultimate cause is a selection pressure imposed by the environment: the decline of oak trees and their replacement by pine trees, gives the mutant allele b an advantage over the originally prevailing a allele. It is the process of natural selection that causes the population as a whole to change from allele a to allele b.

It is easy to confuse proximate and ultimate causation in particular cases, and especially in the complex multilevel process of human evolution. We frequently read, for example, that the evolutionary increase in human intelligence was caused by the invention of controlled fire, or the change to bipedal locomotion, or the employment of persistence hunting, and so forth, alone or in combinations. These innovations were landmarks in human evolution, sure enough, but not prime movers. They were preliminary steps on the pathway to the origin of the present-day high quality of human social behavior. Like the persistent nests and progressive provisioning that brought a few evolving insect species to within reach of eusociality, each step was an adaptation in its own right, with its own ultimate and proximate causes. The final step was the formation of the modern Homo sapiens brain, which produced the creative explosion we continue today.